Abstract

Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) has been known since 1967 but still remains controversial due to incomplete understanding of the basic mechanisms and the selection of inappropriate dosimetric parameters that led to negative studies. The biphasic dose-response or Arndt-Schulz curve in LLLT has been shown both in vitro studies and in animal experiments. This review will provide an update to our previous (Huang et al. 2009) coverage of this topic. In vitro mediators of LLLT such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and mitochondrial membrane potential show biphasic patterns, while others such as mitochondrial reactive oxygen species show a triphasic dose-response with two distinct peaks. The Janus nature of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may act as a beneficial signaling molecule at low concentrations and a harmful cytotoxic agent at high concentrations, may partly explain the observed responses in vivo. Transcranial LLLT for traumatic brain injury (TBI) in mice shows a distinct biphasic pattern with peaks in beneficial neurological effects observed when the number of treatments is varied, and when the energy density of an individual treatment is varied. Further understanding of the extent to which biphasic dose responses apply in LLLT will be necessary to optimize clinical treatments.

Keywords: low level laser therapy, photobiomodulation, biphasic dose response, reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, traumatic brain injury

INTRODUCTION

Low level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) employs visible (generally red) or near-infrared light generated from a laser or light emitting diode (LED) system to treat diverse injuries or pathologies in humans or animals. The light is typically of narrow spectral width between 600nm – 1000nm. The fluence (energy density) used is generally between 1 and 20 J/cm2 while the irradiance (power density) can vary widely depending on the actual light source and spot size; values from 5 to 50 mW/cm2 are common for stimulation and healing, while much higher irradiances (up to W/cm2) can be used for nerve inhibition and pain relief. LLLT is typically used to promote tissue regeneration, reduce swelling and inflammation and relieve pain and is often applied to the injury for 30 seconds to a few minutes or so, a few times a week for several weeks. Unlike other medical laser procedures, LLLT is not an ablative or thermal mechanism, but rather a photochemical effect comparable to photosynthesis in plants whereby the light is absorbed and exerts a chemical change.

Within a decade of the introduction of LLLT in the 1970s it was realized that more does not necessarily mean better. The demonstration of the biphasic dose response curve in LLLT has been hampered by disagreement about exactly what constitutes a “dose”. Many practitioners concentrate on fluence as the principle metric of dose, while others prefer irradiance or illumination time. The use of very small spot sizes by some practitioners has led to the assertion that they delivered hundreds of mW/cm2 from a 50 mW laser. While this statement is mathematically correct it can give the impression that much higher doses of light were given than actually were delivered.

Two years ago we reviewed (Huang et al. 2009) the biphasic dose response in LLLT and found many reports in the literature concerning biphasic dose responses observed in cell cultures, some in animal experiments but no clinical reports. We now believe that the time is right to revisit this interesting topic for two reasons. Firstly because we have found more instances in our laboratory both in vitro with cultured cortical neurons, and in vivo with LLLT of traumatic brain injuries in mouse models. Secondly because advances have been made in mechanistic understanding of how LLLT works at a cellular level that may explain why a little light may be beneficial and at the same time a lot of light might be harmful.

MECHANISMS OF LOW LEVEL LIGHT THERAPY

Basic photobiophysics and photochemistry

According to the First Law of Photochemistry, the photons of light must be absorbed by some molecular photoacceptors or chromophores for photochemistry to occur (Sutherland 2002).The mechanism of LLLT at the cellular level has been attributed to the absorption of monochromatic visible and near infrared (NIR) radiation by components of the cellular respiratory chain (Karu 1989). Phototherapy is characterized by its ability to induce photobiological processes in cells. The effective tissue penetration of light and the specific wavelength of light absorbed by photoacceptors are two of the major parameters to be considered in light therapy. In tissue there is an “optical window” that runs approximately from 650 nm to 1200 nm where the effective tissue penetration of light is maximized. Therefore the use of LLLT in animals and patients almost exclusively involves red and near-infrared light (600–1100-nm) (Karu and Afanas’eva 1995). The action spectrum (a plot of biological effect against wavelength) shows which specific wavelengths of light are most effectively used for biological endpoints as well as for further investigations into cellular mechanisms of phototherapy (Karu and Kolyakov 2005). Fluence (J/cm2) is often referred to as “dose”, though many authors and practitioners of LLLT also refer to energy (Joules) as dose. Not only is this confusing to the novice student of LLLT but it also assumes that the product of power and time (and more importantly power density and time) is the goal rather than the right combination of individual values. This lack of reciprocity has been shown many times before and since our first paper on biphasic dose response and several more authors have reported finding these effects since. Examples of recently published “dose-rate” effects are also reviewed later in this article.

Mitochondrial Respiration and Cytochrome c oxidase

Mitochondria play an important role in energy generation and metabolism and are involved in current research about the mechanism of LLLT effects. The absorption of monochromatic visible and NIR radiation by components of the cellular respiratory chain has been considered as the primary mechanism of LLLT at the cellular level (Karu 1989). Cytochrome c oxidase (Cco) is proposed to be the primary photoacceptor for the red-NIR light range in mammalian cells. Absorption spectra obtained for biological responses to light were found to be very similar to the absorption spectra of Cco in different oxidation states (Karu and Kolyakov 2005).LLLT on isolated mitochondria increased proton electrochemical potential, ATP synthesis (Passarella et al. 1984), increased RNA and protein synthesis (Greco et al. 1989) and increases in oxygen consumption, mitochondrial membrane potential, and enhanced synthesis of NADH and ATP.

ROS release and Redox signaling pathway

Mitochondria are an important source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within most mammalian cells. Mitochondrial ROS may act as a modulatable redox signal, reversibly affecting the activity of a range of functions in the mitochondria, cytosol and nucleus. ROS are very small molecules that include oxygen ions such as superoxide, free radicals such as hydroxyl radical, hydrogen peroxide, and organic peroxides. ROS are highly reactive with biological molecules such as proteins, nucleic acids and unsaturated lipids. ROS are also involved in the signaling pathways from mitochondria to nuclei. It is thought that cells have ROS or redox sensors whose function is to detect potentially harmful levels of ROS that may cause cell damage, and then induce expression of anti-oxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutase and catalase.

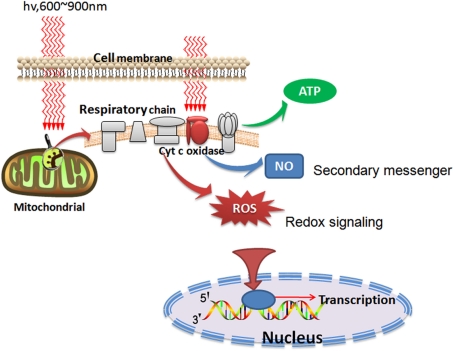

LLLT was reported to produce a shift in overall cell redox potential in the direction of greater oxidation (Karu 1999) and increased ROS generation and cell redox activity have been demonstrated (Lubart et al. 2005). These cytosolic responses may in turn induce transcriptional changes. Several transcription factors are regulated by changes in cellular redox state, but the most important one is nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). Figure 1 graphically illustrates some of the intracellular signaling pathways that are proposed to occur after LLLT.

FIG. 1.

Schematic depiction of the cellular signaling pathways triggered by LLLT. After photons are absorbed by chromophores in the mitochondria, respiration and ATP is increased but in addition signaling molecules such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) are also produced.

NO release and NO signaling

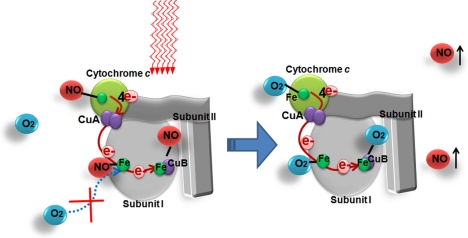

There have been reports of the production and/or release of NO from cells after in vitro LLLT. It is possible that the delivery of low fluences of red/NIR light produces a small amount of NO from mitochondria by dissociation from intracellular stores (Shiva and Gladwin 2009), such as nitrosothiols (Borutaite et al. 2000), NO bound to hemoglobin or myoglobin (Lohr et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009) or by dissociation of NO from Cco (Lane 2006) as depicted in Figure 2. A second mechanism for NO production is by light-mediated increase of the nitrite reductase activity of cytochrome c oxidase (Lane 2006). A third possibility is that light can cause increase of the activity of an isoform of nitric oxide synthase (Poyton and Ball 2011), possibly by increasing intracellular calcium levels. This low concentration of NO produced by illumination is proposed to be beneficial through cell-signaling pathways (Ball et al. 2011).

FIG. 2.

One possible theory that can explain the simultaneous increase in respiration an production of nitric oxide is the photodissociation of bound NO that is inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase by displacing oxygen.

BIPHASIC DOSE RESPONSES IN LLLT

Many reports of biphasic dose responses in LLLT were reviewed in our previous contribution and for convenience we have assembled these reports into Tables. Table 1 lists reports on cultured cells in vitro, Table 2 lists those reports in animal models in vivo, while Table 3 contains the only report of biphasic dose response in clinical studies.

TABLE 1.

Biphasic dose response studies of LLLT in vitro.

| Year | Cells | Laser characteristics | Fluence | Irradiance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Lymphocytes in vitro | “threshold phenomenon” | Mester et al. 1978 | ||

| 1990 | Macrophage cell lines (U-937) | 820nm Laser; 120mW/cm2; 2.4J/ cm2 to 9.6J/cm2 | Cell proliferation: Maximum at 7.2J/cm2 least at 9.6J/cm2 | Bolton et al. 1990 | |

| 1991 | Macrophage cell lines (U-937) | 820nm Laser; 2.4J/cm2 or 7.2J/cm2; 400mW/ cm2 or 800mW/ cm2 | cell proliferation increased at 400mW/ cm2; Cell viability reduced at 800mW/cm2 | Bolton et al. 1991 | |

| 1994 | Human oral mucosal fibroblast cells | 812nm laser; 4.5mW/cm2; | Cell proliferation peak at 0.45 J/cm2; less at 1.422J/cm2 | Loevschall and Arenholt-Bindslev 1994 | |

| 2001 | Chinese hamster ovary and human fibroblast cells | He-Ne laser;1.25 mW/cm2; 0.06 to 0.6J/cm2 | Cell proliferation peak at 0.18 J/cm2; less at 0.6J/cm2. | al-Watban and Andres 2001 | |

| 2003 | human fibroblast cells | 628nm LED; 11.46 mW/cm2; 0, 0.44, 0.88, 2.00, 4.40, and 8.68 J /cm2 | Cell proliferation maximum at 0.88 J/cm2; reduced at 8.68 J/cm2 | Zhang et al. 2003 | |

| 2005 | Human HEP-2 and murine L-929 cell lines | 670 nm LED; 5 J/cm2 per treatment; Total 50J/cm2/day; 1 to 4 treatments/day | Cell proliferation bigger at 2 treatments/day | Brondon et al. 2005 | |

| 2005 | Hela cells | wavelength range of 580–860 nm | DNA synthesis rate maximum at 0.1 J/cm2 with 0.8 mW/cm2 | Karu and Kolyakov 2005 | |

| 2005 | Wounded fibroblasts | 632.8nm laser; 2mW/cm2; 0.5, 2.5, 5.0 or 10.0 J/cm2 | Cell proliferation maximum at a single dose of 2.5J/cm2; Cellular damage at 10J/cm2 | Hawkins and Abrahamse 2005 | |

| 2006 | Wounded fibroblasts | 632.8nm laser; 5.0 J/ cm2 or 16J/ cm2 | Cell proliferation and cell viability increased at 5 J/cm2; decreased at 10 and 16 J/cm2 | Hawkins and Abrahamse 2006a | |

| 2006 | Wounded fibroblasts | 632.8nm laser; 5.0 J/cm2 or 16J/cm2 | Cell migration and proliferation increased at a single dose of 5.0 J/cm2 and two or three doses of 2.5 J/cm2; inhibited at 16 J/cm2 | Hawkins and Abrahamse 2006b | |

| 2007 | Human Neural Progenitor Cells (NHNPCs) | 810nm; 0.2J/ cm2; 50mW/cm2 and 100mW/ cm2 | Neurite outgrowth greater at 50mW/cm2; less at 100mW/cm2 | Anders et al. 2007 | |

| 2009 | Rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes | 810nm laser_1, 3, 5, 10, 20 and 50 J/cm2 | Cell proliferation increased at 5 J/cm2 (16.7 mW/cm2); Lower at 50 J/cm2 | Yamaura et al. 2009 | |

| 2009 | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | 810nm laser; 0.003,0.03,0.3,3 or 30J/cm2 | NF-κB activation maximum at 0.3 J/cm2; decreased at 3 J/cm2 and 30 J/cm2 | Chen et al. 2009 |

TABLE 2.

Biphasic dose response studies of LLLT in vivo (animal models).

| Year | Tissue | Laser characteristics | Fluence | Irradiance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | wound closure | He-Ne laser4 J/cm2 | Wound healing best at 45 mW/cm2; least at 12.4 mW/cm2 | Ginsbach 1979 | |

| 2001 | Induced heart attacks in rats | 810 nm laser; 2.5 to 20mW/cm2 ; | Reductions of infarct size maximum at 5mW/cm2 Lower effects both at 2.5mW/cm2 and 20mW/cm2 |

Oron et al. 2001 | |

| 2005 | Mouse pleurisy induced by Carrageenan | 650nm laser; 2.5 mW in 0.08 cm2; 3 J/cm2, 7.5 J/cm2, and 15 J/cm2 | Inflammatory cell migration reduction most at 7.5 J/cm2; Less at 3 and 15 J/cm2 | Lopes-Martins et al. 2005 | |

| 2007 | Healing of pressure ulcers in mice | 670nm LED; 5 J/cm2 at 0.7, 2, 8 or 40mW/cm2 | Healing significant improved only at 8mW/cm2;Less at 0.7, 2, and 40 mW/cm2 | Lanzafame et al. 2007 | |

| 2007 | Full thickness dorsal excisional wound in BALB/c mice | a single exposure from 635, 670, 720 or 820nm filtered lamp; 1, 2, 10 and 50 J/cm2; 100 mW/cm2 10, 20, 100 and 500 seconds | Healing effect best at 2 J/cm2 for 635nm light; worse at 50 J/cm2 for most wavelengths compared to no treatment | 820nm was the best wavelength | Demidova-Rice et al. 2007 |

| 2007 | Inflammatory arthritis induced by zymosan in rats | 810-nm laser; 3 and 30 J/cm2; 5 mW/cm2 and 50 mW/cm2 | 30 J/cm2 was better than 3 J/cm2 at 50mW/cm2 | 3 J/cm2 has effective at 5mW/cm2 but not 50mW/cm2 | Castano et al. 2007 |

TABLE 3.

Biphasic dose response studies of LLLT in clinical studies.

| Year | Patients | Laser characteristics | Fluence | Irradiance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Patients with post herpetic neuralgia of the facial type | 830nm lasers; 60mW laser and 150mW laser; irradiance point at 4mm in diameter | Pain reduction greater at 150mW laser; less at 60mW laser when exposure to the same time. | Hashimoto et al. 1997 |

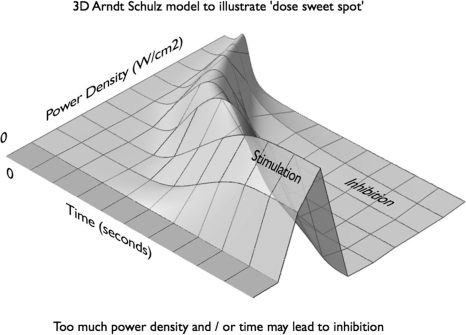

Figure 3 shows a 3D depiction of the Arndt Schulz model to illustrate a possible dose “sweet spot” at the target tissue. This graph suggests that insufficient power density or too short a time will have no effect on the pathology, that too much power density and / or time may have inhibitory effects and that there may be an optimal balance between power density and time that produces a maximal beneficial effect. There even may be a (low) power density for which infinite irradiation time would only have positive effects and no inhibitory effect. We believe that the absolute figures will be different at different wavelengths, tissue types, redox states, and may be affected further by different pulse parameters.

FIG. 3.

Three-dimensional model of the Arndt-Schulz curve illustrating how either irradiance or illumination time (fluence) can have biphasic dose response effects in LLLT.

CURRENT BIPHASIC DOSE RESPONSE STUDIES IN LLLT

In this section we cover the new reports of biphasic dose responses in LLLT that have been published in the last two years since our previous review.

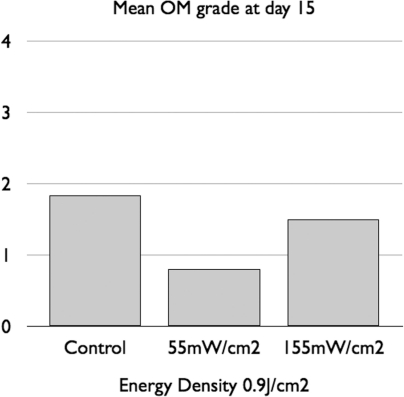

In an oral mucositis hamster model Lopes and coworkers (Lopes et al. 2009) delivered 660-nm laser at two different irradiances (55 mW/cm2 for 16 seconds per point or 155 mW/cm2 for 6 seconds per point). Both regimens delivered 0.9 J/cm2 per point. On day 7, 11 and 15 the authors reported reduced severity of clinical mucositis and lower levels of COX-2 staining in the 55 mW/cm2 group and that the 155 mW/cm2 had no significant differences when compared with controls. This data is summarized in Figure 4.

FIG. 4.

Mean grading of oral mucositis (OM) in a hamster cheek pouch model treated with 0.9 J/cm2 of 660-nm laser at two different irradiances (55 mW/cm2 for 16 seconds per point or 155 mW/cm2 for 6 seconds per point). Graph redrawn from data contained in (Lopes, Plapler et al. 2009).

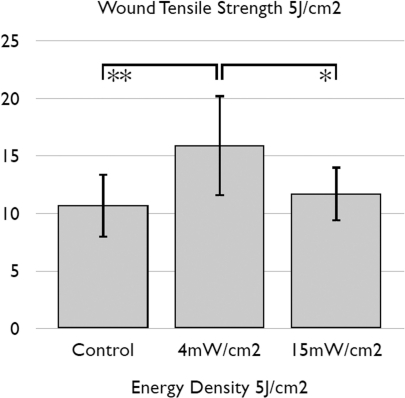

Gal et al (Gal et al. 2009) compared the effects of delivering 5 J/cm2 of 670-nm laser at different power densities on wound tensile strength in a rat model. They found (Figure 5) that 670 nm laser achieved a significant effect using 4mW/cm2 applied for 1,250 seconds (20 mins 50 seconds) but that this effect was lost if the same 5J/cm2 fluence was delivered at 15 mW/cm2 for 333 seconds (5 mins 33 seconds).

FIG. 5.

Mean wound tensile strength obtained after delivering 5 J/cm2 of 670-nm laser at different power densities (4mW/cm2 applied for 1,250 seconds or 15 mW/cm2 for 333 seconds). Graph redrawn from data contained in (Gal, Mokry et al. 2009).

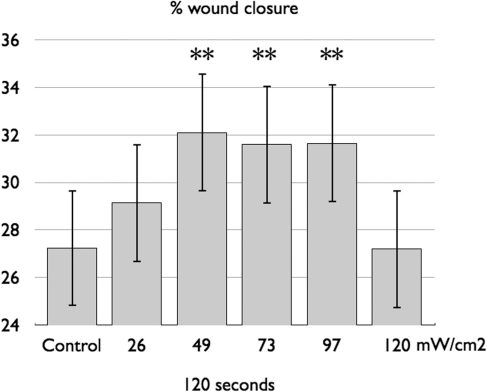

(Skopin and Molitor 2009) studied the effects of different influences of 980 nm laser on a human fibroblast in vitro model of wound healing. A small pipette was used to induce a wound in fibroblast cell cultures, which were exposed to a range of laser doses (1.5–66 J/cm2). Exposure to low- and medium-dose laser light accelerated cell growth, whereas high-intensity light negated the beneficial effects of laser exposure as shown in Figure 6.

FIG. 6.

Mean percentage of healing induced in a scratch wounded culture of human fibroblasts using different fluences (constant time, increasing irradiance) of 980-nm laser. Graph redrawn from data contained in (Gal, Mokry et al. 2009).

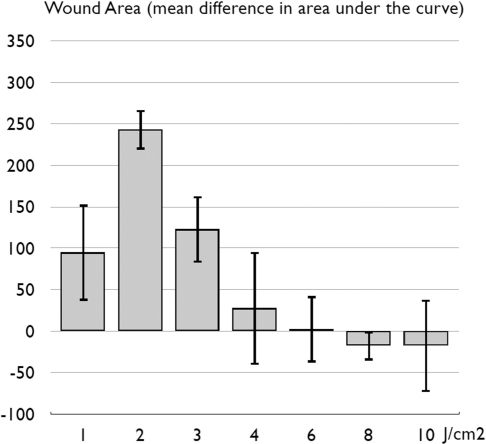

(Prabhu et al. 2010) performed a dose response study by applying a 7 mW HeNe (632.8-nm) laser with a power density of 4 mW/cm2 to 15×15 mm excisional wounds on Swiss albino mice for a range of irradiation times from 249 seconds (4.15 mins) up to 2,290 seconds (41.46 mins). As Figure 7 shows, there was a clear biphasic response (including a possible inhibitory effect) with changes in irradiation time and therefore fluence.

FIG. 7.

Mean area under the curve of wound area over time in a mouse excisional wound healing model treated with a 7 mW (power density of 4 mW/cm2) HeNe (632.8-nm) laser for times ranging from 249 to 2,290 seconds. Graph redrawn from data contained in (Prabhu, Rao et al. 2010).

BIPHASIC LLLT DOSE RESPONSE STUDIES IN CULTURED NEURONS AND TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY MODELS IN MICE

LLLT studies on cultured cortical neurons

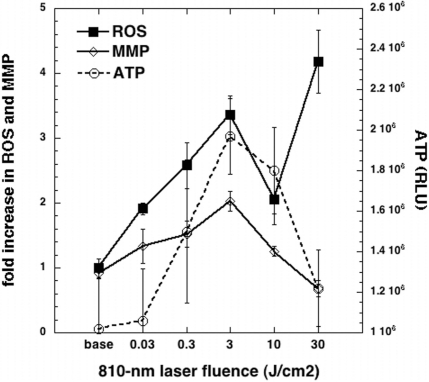

In order to elucidate the mechanism responsible for the beneficial effect reported by LLLT for brain related disorders, we carried out studies to look into effects of 810 nm laser on different cellular signaling molecules in primary cortical neurons. The primary cortical neurons were isolated from brains taken from embryonic mice. We irradiated the neurons with different fluences of 0.03, 0.3, 3, 10 or 30 J/cm2 delivered at a constant irradiance of 25 mW/cm2, and subsequently the intracellular levels of ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and ATP was measured. The changes in mitochondrial function were studied in terms of ATP and MMP. Low-level light was found to induce a significant increase in ATP and MMP at lower fluences and a decrease at higher fluence. ROS was induced significantly by light at all light doses but there was a distinctive pattern of a double peak with the first peak coinciding with the other peaks of ATP and MMP at 3 J/cm2 (Figure 8). However in contrast to ATP and MMP there was a second larger rise in ROS at 30 J/cm2 that coincided with the reduction in MMP below baseline. The results of the this study suggested that LLLT at lower fluences is capable of inducing mediators of cell signaling process which in turn may be responsible for the biomodulatory effects of the low level laser. Conversely at higher fluences beneficial mediators are reduced but potentially harmful mediators are increased. Thus this study offered an explanation for the biphasic dose response induced by LLLT.

FIG. 8.

Mean expression levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS, measured by MitoSox red fluorescence), mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP, measured by red/green fluorescence ration of JC1 dye) and ATP (measured by firefly luciferase assay) in primary mouse cortical neurons treated with various fluences of 810-laser delivered at 25 mW/cm2 over times varying from 1.2 to 1200 seconds.

LLLT in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury

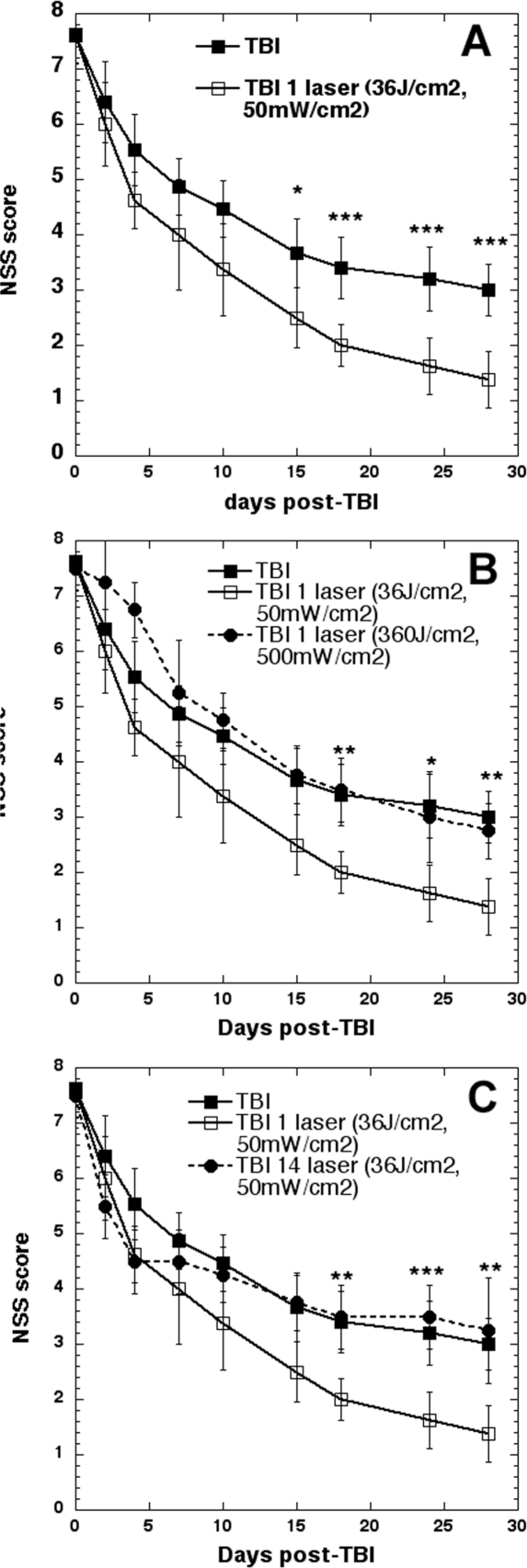

We have been studying the effect of transcranial laser (810-nm) on mouse models of traumatic brain injury. The model involves a controlled cortical impact using a pneumatic piston device through a craniotomy followed by closure of the head. This injury can be adjusted in severity to produce a neurological severity score (NSS based on a panel of standardized behavioral tests) of 7–8 on a scale of 0 (normal mice) to 10 (severe brain injury that causes death). The basic finding was that delivering a single dose of 36 J/cm2 810-nm laser delivered at 50 mW/cm2 (12 minutes illumination time) in a spot of 1-cm diameter centered on the top of the mouse head at a time point of 4 hours post-TBI was highly effective in ameliorating the neurological symptoms suffered by the mice (Figure 9A). When we delivered 10 times as much 810-nm laser (360 J/cm2 at 500 mW/cm2) also taking 12 minutes the beneficial effect totally disappeared, and at early time points (1–6 days) the high fluence appeared to be worse than no treatment (Figure 9B).

FIG. 9.

Transcranial laser therapy (36 J/cm2 of 810-nm laser delivered at 50 mW/cm2 (12 minutes illumination time) in a spot of 1-cm diameter centered on the top of the mouse head) was used to treat mice with controlled cortical impact TBI four hours after injury. (A) Significant improvement in neurological severity score continuing for 4 weeks after a single treatment. (B) Delivering ten times more light by increasing irradiance tenfold (500 mW/cm2) loses all therapeutic benefit, and produces worse performance soon after laser. (C) Repeating beneficial laser treatment daily for 14 days loses benefit in performance after 5 days.

When we repeated the effective laser treatments 14 times (36 J/cm2 delivered at 50-mW/cm2 once a day for 14 days starting 4 hours post-TB) we found a very interesting result (Figure 9C). For the first 4 days the improvement in NSS in the repeated laser group was marginally better than the single treatment. However on day 5 the gradual improvement ceased and as the laser was repeated the NSS got closer to that of untreated TBI mice until at day 14 it actually crossed over. Although the differences were not statistically significant it appeared that from day 16 until day 28 the mice that received 14 laser treatments did worse than those that received no treatment at all.

POSSIBLE EXPLANATIONS FOR BIPHASIC DOSE RESPONSE IN LLLT

The triphasic dose response we have observed for ROS production in cultured cortical neurons (see Fig 7) suggests an explanation for the biphasic dose response. The hypothesis is that there are two kinds of ROS. Good ROS are produced at fairly low fluences of light. The reason for the production of good ROS is likely to be connected with stimulation of mitochondrial electron transport as shown by increases in MMP and increases in ATP production. These good ROS can initiate beneficial cell signaling pathwas leading to activation of redox sensitive transcription factors such as NF-κB (Chandel et al. 2000; Groeger et al. 2009). NF-κB activation induces expression of a large number of gene products related to cell proliferation and survival (Karin and Lin 2002; Brea-Calvo et al. 2009). As the fluence of light is increased the beneficial ROS production in the mitochondria decreases in tandem with reductions in MMP and a drop-off in ATP production. Then when even more light is delivered there is a second peak in ROS production, which we will call bad ROS. Bad ROS can damage the mitochondria leading to a drop in MMP below baseline levels and presumably can lead to initiation of apoptosis by the mitochondrial pathway including cytochrome c release. It remains to be seen whether the good and bad ROS are identical species and just differ in amount, or whether they are chemically different species. For instance it may be hypothesized that the good ROS consists mainly of superoxide while the bad ROS consists of more damaging ROS such as hydroxyl radicals and peroxynitrite. In Figure 7 we used just one type of fluorescent ROS indicator (mitoSOX red), which is commonly supposed to be specific for superoxide but will likely also be activated by hydroxyl radicals and peroxynitrite.

There have been several studies showing that relatively high doses of light can induce apoptosis in various cell types via ROS-mediated signaling pathways (Huang et al. 2011). Meanwhile, there is an important proapoptotic signaling pathway has been identified which involves Akt/GSK3beta inactivation after high-fluence low-power laser irradiation (HF-LPLI) (Huang, Wu et al. 2011). This research extended the knowledge of the biological mechanisms of cytotoxicity induced by HF-LPLI. In one of the studies it was shown that HF-LPLI does not activate caspase-8, indicating that the induced apoptosis was initiated directly from mitochondrial ROS generation and a decrease in MMP, independent of cas-pase-8 activation (Wu et al. 2007). Another study revealed HF-LPLI induced cell apoptosis via the CsA-sensitive MPT, which was ROS-dependent. They also showed a secondary signaling pathway through Bax activation. It was concluded that link between MPT and triggering ROS could be a fundamental phenomenon in HF-LPLI-induced cell apoptosis (Wu et al. 2009).

Further work is necessary to fully elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for the biphasic dose response in LLLT. Besides the role of ROS, which we have discussed above, the role of another Janus-type mediator, nitric oxide (NO) may play a role. If high fluences of light could produce high concentrations of NO, this might result in cytotoxicity via formation of peroxynitrite or other reactive nitrogen species (Hirst and Robson 2010).

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The number of instances of biphasic dose response reported in the LLLT literature is increasing as time progresses. This increase may be due to an increasing realization that the phenomenon is real, and thus prompting investigators to look for it. At present there has been no convincing report of biphasic dose responses occurring in patients, but several systematic reviews and meta analyses of randomized controlled trials in LLLT have found (Bjordal et al. 2003; Tumilty et al. 2009) that some ineffective trials may be explained by over-dosing, in that the guidelines set by World Association for Laser Therapy (www.walt.nu) were exceeded. As more clinical trials of LLLT are reported there is an increasing likelihood that this unfortunate state of affairs will continue unless the dosimetry is designed to take into account the biphasic dose response phenomenon. Moreover it is unknown to what extent the parameters needed for the onset of the biphasic dose response will vary in a highly heterogeneous patient population, as compared with a highly uniform population of experimental animals (inbred lab animals are genetically identical).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI050875, Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology (DAMD17-02-2-0006), CDMRP Program in TBI (W81XWH-09-1-0514) and Air Force Office of Scientific Research (FA9950-04-1-0079).

REFERENCES

- al-Watban FA, Andres BL. The effect of He-Ne laser (632.8 nm) and Solcoseryl in vitro. Lasers Med Sci. 2001;16(4):267–275. doi: 10.1007/pl00011363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders J, Romanczyk T, Moges H, Ilev I, Waynant R, Longo L. Light Interaction With Human Central Nervous System Progenitor Cells. NAALT conference proceedings; 2007. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ball KA, Castello PR, Poyton RO. Low intensity light stimulates nitrite-dependent nitric oxide synthesis but not oxygen consumption by cytochrome c oxidase: Implications for phototherapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011;102(3):182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjordal JM, Couppe C, Chow RT, Tuner J, Ljunggren EA. A systematic review of low level laser therapy with location-specific doses for pain from chronic joint disorders. Aust J Physiother. 2003;49(2):107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60127-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Young S, Dyson M. Macrophage responsiveness to light therapy: a dose response study. Laser Ther. 1990;2:101–106. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900090513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P, Young S, Dyson M. Macrophage responsiveness to light therapy with varying power and energy densities. Laser Therapy. 1991;3(3):105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Borutaite V, Budriunaite A, Brown GC. Reversal of nitric oxide-, peroxynitrite- and S-nitrosothiol-induced inhibition of mitochondrial respiration or complex I activity by light and thiols. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2000;1459(2–3):405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brea-Calvo G, Siendones E, Sanchez-Alcazar JA, de Cabo R, Navas P. Cell survival from chemotherapy depends on NF-kappaB transcriptional up-regulation of coenzyme Q biosynthesis. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondon P, Stadler I, Lanzafame RJ. A study of the effects of phototherapy dose interval on photobiomodulation of cell cultures. Lasers Surg Med. 2005;36(5):409–413. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano AP, Dai T, Yaroslavsky I, Cohen R, Apruzzese WA, Smotrich MH, Hamblin MR. Low-level laser therapy for zymosan-induced arthritis in rats: Importance of illumination time. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39(6):543–550. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Trzyna WC, McClintock DS, Schumacker PT. Role of oxidants in NF-kappa B activation and TNF-alpha gene transcription induced by hypoxia and endotoxin. J Immunol. 2000;165(2):1013–1021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC-H, Arany PR, Huang Y-Y, Tomkinson EM, Saleem T, Yull FE, Blackwell TS, Hamblin MR. Low level laser therapy activates NF-κB via generation of reactive oxygen species in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proc. SPIE 7165. 2009:71650B. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidova-Rice TN, Salomatina EV, Yaroslavsky AN, Herman IM, Hamblin MR. Low-level light stimulates excisional wound healing in mice. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39(9):706–715. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal P, Mokry M, Vidinsky B, Kilik R, Depta F, Harakalova M, Longauer F, Mozes S, Sabo J. Effect of equal daily doses achieved by different power densities of low-level laser therapy at 635 nm on open skin wound healing in normal and corticosteroid-treated rats. Laser Med Sci. 2009;24(4):539–547. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsbach G. Laser induced stimulation of wound healing in bad healing wounds; Proc Laser ‘79 Opto Elektronics Conf Munich; IPC Science and Technology Press Guildford UK. 1979. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Greco M, Guida G, Perlino E, Marra E, Quagliariello E. Increase in RNA and protein synthesis by mitochondria irradiated with helium-neon laser. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163(3):1428–1434. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)91138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeger G, Quiney C, Cotter TG. Hydrogen peroxide as a cell-survival signaling molecule. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(11):2655–2671. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Kemmotsu O, Otsuka H, Numazawa R, Ohta Y. Efficacy of laser irradiation on the area near the stellate ganglion is dose-dependent: a double-blind crossover placebo-controlled study. Laser Therapy. 1997;7:5. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D, Abrahamse H. Biological effects of helium-neon laser irradiation on normal and wounded human skin fibroblasts. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23(3):251–259. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins D, Abrahamse H. Effect of multiple exposures of low-level laser therapy on the cellular responses of wounded human skin fibroblasts. Photomed Laser Surg. 2006b;24(6):705–714. doi: 10.1089/pho.2006.24.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins DH, Abrahamse H. The role of laser fluence in cell viability, proliferation, and membrane integrity of wounded human skin fibroblasts following helium-neon laser irradiation. Lasers Surg Med. 2006a;38(1):74–83. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst DG, Robson T. Nitrosative stress as a mediator of apoptosis: implications for cancer therapy. Curr Pharm Design. 2010;16(1):45–55. doi: 10.2174/138161210789941838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Wu S, Xing D. High fluence low-power laser irradiation induces apoptosis via inactivation of Akt/GSK3beta signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(3):588–601. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Chen AC, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy. Dose Response. 2009;7(4):358–383. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.09-027.Hamblin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(3):221–227. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karu TI. Laser biostimulation: a photobiological phenomenon. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1989;3(4):638–640. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(89)80088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karu TI. Primary and secondary mechanisms of action of visible to near-IR radiation on cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1999;49(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(98)00219-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karu TI, Afanas’eva NI. Cytochrome c oxidase as the primary photoacceptor upon laser exposure of cultured cells to visible and near IR-range light. Dokl Akad Nauk. 1995;342(5):693–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karu TI, Kolyakov SF. Exact action spectra for cellular responses relevant to phototherapy. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23(4):355–361. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N. Cell biology: power games. Nature. 2006;443(7114):901–903. doi: 10.1038/443901a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzafame RJ, Stadler I, Kurtz AF, Connelly R, Peter TA, Sr, Brondon P, Olson D. Reciprocity of exposure time and irradiance on energy density during photoradiation on wound healing in a murine pressure ulcer model. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39(6):534–542. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loevschall H, Arenholt-Bindslev D. Effect of low level diode laser irradiation of human oral mucosa fibroblasts in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 1994;14(4):347–354. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900140407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr NL, Keszler A, Pratt P, Bienengraber M, Warltier DC, Hogg N. Enhancement of nitric oxide release from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin by red/near infrared radiation: Potential role in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes-Martins RA, Albertini R, Martins PS, Bjordal JM, Faria Neto HC. Spontaneous effects of low-level laser therapy (650 nm) in acute inflammatory mouse pleurisy induced by Carrageenan. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23(4):377–381. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes NN, Plapler H, Chavantes MC, Lalla RV, Yoshimura EM, Alves MT. Cyclooxygenase-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in 5-fluorouracil-induced oral mucositis in hamsters: evaluation of two low-intensity laser protocols. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(11):1409–1415. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0603-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubart R, Eichler M, Lavi R, Friedman H, Shainberg A. Low-energy laser irradiation promotes cellular redox activity. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23(1):3–9. doi: 10.1089/pho.2005.23.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mester E, Nagylucskay S, Waidelich W, Tisza S, Greguss P, Haina D, Mester A. Effects of direct laser radiation on human lymphocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 1978;263(3):241–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00446940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oron U, Yaakobi T, Oron A, Hayam G, Gepstein L, Rubin O, Wolf T, Ben Haim S. Attenuation of infarct size in rats and dogs after myocardial infarction by low-energy laser irradiation. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28(3):204–211. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarella S, Casamassima E, Molinari S, Pastore D, Quagliariello E, Catalano IM, Cingolani A. Increase of proton electrochemical potential and ATP synthesis in rat liver mitochondria irradiated in vitro by helium-neon laser. FEBS Lett. 1984;175(1):95–99. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80577-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyton RO, Ball KA. Therapeutic photobiomodulation: nitric oxide and a novel function of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase. Discov Med. 2011;11(57):154–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu V, Rao SB, Rao NB, Aithal KB, Kumar P, Mahato KK. Development and evaluation of fiber optic probe-based helium-neon low-level laser therapy system for tissue regeneration—an in vivo experimental study. Photochem Photobiol. 2010;86(6):1364–1372. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2010.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiva S, Gladwin MT. Shining a light on tissue NO stores: near infrared release of NO from nitrite and nitrosylated hemes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopin MD, Molitor SC. Effects of near-infrared laser exposure in a cellular model of wound healing. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2009;25(2):75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2009.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland JC. Biological effects of polychromatic light. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;76(2):164–170. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)076<0164:beopl>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumilty S, Munn J, McDonough S, Hurley DA, Basford JR, Baxter GD. Low Level Laser Treatment of Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis Photomed Laser Surg Ahead of print. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wu S, Xing D, Gao X, Chen WR. High fluence low-power laser irradiation induces mitochondrial permeability transition mediated by reactive oxygen species. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(3):603–611. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Xing D, Wang F, Chen T, Chen WR. Mechanistic study of apoptosis induced by high-fluence low-power laser irradiation using fluorescence imaging techniques. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12(6):064015. doi: 10.1117/1.2804923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaura M, Yao M, Yaroslavsky I, Cohen R, Smotrich M, Kochevar IE. Low level light effects on inflammatory cytokine production by rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. Lasers Surg Med. 2009;41(4):282–290. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Mio Y, Pratt PF, Lohr N, Warltier DC, Whelan HT, Zhu D, Jacobs ER, Medhora M, Bienengraeber M. Near infrared light protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and reoxygenation injury by a nitric oxide dependent mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Song S, Fong CC, Tsang CH, Yang Z, Yang M. cDNA microarray analysis of gene expression profiles in human fibroblast cells irradiated with red light. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120(5):849–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]