Abstract

Many naturally occurring isothiocyanates (ITCs) show highly promising chemopreventive activities. Humans are commonly exposed to these compounds through consumption of cruciferous vegetables which are the main source of dietary ITCs. Dietary ITCs may play an important role in cancer prevention and in the well-recognized cancer preventive activities of cruciferous vegetables. A generic analytical method, namely the 1,2-benzenedithiol-based cyclocondensation assay, was previously developed for quantitation of ITCs and their in vivo metabolites. This method has been widely used and has contributed greatly to research on chemoprevention by ITCs. In this article, the discovery and development of the cyclocondensation assay are recapitulated, and its sensitivity and specificity as well as its advantages and limitations are scrutinized. Moreover, detailed discussion is also provided to show how this assay has been used to advance our understanding of the cancer chemopreventive potential and the mechanism of action of ITCs.

Keywords: Phytochemical, chemoprevention, cruciferous vegetable, diet and cancer prevention, isothiocyanate quantitation

Introduction

Isothiocyanates (ITCs) are a family of small molecules characterized by the presence of an –N=C=S group. They are widely distributed in plants, especially in cruciferous vegetables. Some vegetables are particularly abundant in certain ITCs, such as sulforaphane (SF) in broccoli and broccoli sprouts (Fahey et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1992b), allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) in horseradish root and mustard seed (Uematsu et al., 2002), benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) in garden cress (Gil and Macleod, 1980), and phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) in watercress (Chung et al., 1992). Indeed, the pungent flavor of some of these vegetables arises primarily from these compounds. ITCs are synthesized and stored in plants as glucosinolates and are generated from the latter through myrosinase-catalyzed hydrolysis. More than 120 glucosinolates have been identified in plants, but some glucosinolates do not finally generate ITCs (Fahey et al., 2001). Numerous studies in cells and animals have shown the cancer-preventive activities of various ITCs (Hecht, 1999; Zhang, 2010; Zhang and Talalay, 1994; Zhang and Tang, 2007). Epidemiological studies have also shown an inverse association between consumption of dietary ITCs and risk of cancer (Zhang, 2004). These findings have led to wide-spread interest in dietary ITCs, which may play an important role in cancer prevention in humans and in the well-recognized cancer preventive activities of cruciferous vegetables.

The central carbon atom of the –N=C=S group in most ITCs is strongly electrophilic and can react with oxygen-, sulfur- or nitrogen-centered nucleophiles, yielding thiocarbamates, dithiocarbamates or thiourea derivatives, respectively. Thus, the reaction of phenyl ITC with the amino groups of amino acids is the basis for Edman degradation for sequencing peptides (Edman, 1956). In vivo, the carbon atom of the –N=C=S reacts primarily with the cysteine thiol of glutathione (GSH), as described later. We reported in the early 1990s that ITCs also react with vicinal dithiols to form initially dithiocarbamates but finally five-membered cyclic products with release of the corresponding amines (Zhang et al., 1992a). This discovery led to the development of a relatively simple but highly sensitive and quantitative method, namely the cyclocondensation assay, for measurement of ITCs and their metabolites in plant extracts and biospecimens (Zhang et al., 1992a; Zhang et al., 1996). To date, this assay has been used by many investigators in a wide variety of ITC studies and has greatly facilitated the evaluation of these compounds as potential cancer preventive agents. In this article, I intend to recount the discovery and development of the cyclocondensation assay, to discuss its sensitivity and specificity as well as its advantages and limitations, and to describe how this assay has been used to advance our understanding of the cancer chemopreventive potential and the mechanism of action of ITCs.

The reaction of ITCs with vicinal dithiols

When propyl ITC was incubated with 2,3-dimercaptopropanol in an aqueous solution under slightly basic conditions, the ultraviolet absorption spectrum of the solution indicated rapid formation of a dithiocarbamate (absorbing maximally near 270 nm with a shoulder at 250 nm) (Fabian et al., 1967). Upon longer incubation, however, the absorption spectrum of the solution shifted with a well-defined single isosbestic point to one that absorbed light maximally at longer wavelengths with greater intensity, indicating conversion of the dithiocarbamate to a new product (Zhang et al., 1992a). This new product was subsequently isolated and identified as 4-hydroxymethyl-1,3-dithiolane-2-thione (Zhang et al., 1992a). Additional experiments revealed that the reaction was specific neither to propyl ITC nor to 2,3-dimercaptopropanol, and followed the general mechanism illustrated in Figure 1. Thus, attack on the carbon atom of the –N=C=S group of an ITC molecule by a thiol group of a vicinal dithiol, which gives rise to a dithiocarbamate, is followed by a second attack on the same carbon by the adjacent thiol group, resulting in formation of a five-membered 1,3-dithiolane-2-thione and the corresponding amine. Although intramolecular cyclization between ITCs and vicinal amino groups or vicinal amino and thiol groups had previously been demonstrated (Mukerjee and Ashare, 1991), a cyclocondensation with vicinal dithiols had not been reported. Thus, a new chemical reaction of ITC had been discovered. This reaction was subsequently shown to be useful for generating primary amines in good yields from alkyl and aryl ITCs (Cho and Posner, 1992), but we also realized that it might be useful for measuring ITCs by quantifying the cyclic product, providing a generic analytical method for ITCs.

Figure 1.

The cyclocondensation reaction of ITCs with vicinal dithioles. B: stands for a base.

The 1,2-benzenedithiol-based cyclocondensation assay and its sensitivity

A comparison of several vicinal dithiols identified 1,2-benzenedithiol (BDT), which is commercially available, as the favorable reagent: the cyclocondensation product, 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione, showed a high molar extinction coefficient at the long wavelength (ε = 23,000 M−1 cm−1 at 365 nm); the product formed rapidly and was very stable under a variety of conditions, including heating for 18 h at 65 °C and pH 8.5 (Zhang et al., 1992a). All aliphatic and aromatic ITCs, except tertiary ITCs, reacted quantitatively with an excess of BDT. While the rate of the cyclocondensation reaction varied among different ITCs, and with pH and temperature, we were able to find a simple reaction condition, as described later, under which every reactive ITC tested was fully converted to 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione.

ITCs are metabolized in vivo primarily through the mercapturic acid pathway. They first undergo rapid conjugation with GSH, which takes place spontaneously but is further promoted by glutathione S-transferase (GST). The GSH moiety of the conjugate then undergoes further enzymatic modification to form sequentially the cysteinylglycine-, cysteine-, and N-acetylcysteine (NAC)-conjugates, which are excreted in urine (Figure 2) (Brusewitz et al., 1977; Egner et al., 2008; Jiao et al., 1994). We demonstrated that these metabolites (dithiocarbamates) could undergo the same cyclocondensation reaction with BDT stoichiometrically (Figure 2) (Zhang et al., 1996). This finding suggested the potential utility of this assay for measurement of human and animal exposure to ITC, for determination of the bioavailability of ITC from cruciferous vegetables, and for elucidation of the mechanisms of action of these compounds. Indeed, this assay has been used in various studies in cultured cells, animals and humans, some of which are discussed later.

Figure 2.

ITC metabolism through the mercapturic acid pathway and reaction of ITCs and their metabolites with 1,2-benzenedithiol. GST, glutathione S-transferase; GT, γ-glutamyltranspeptidase; CG, cysteinylglycinase, AT, N-acetyltransferase.

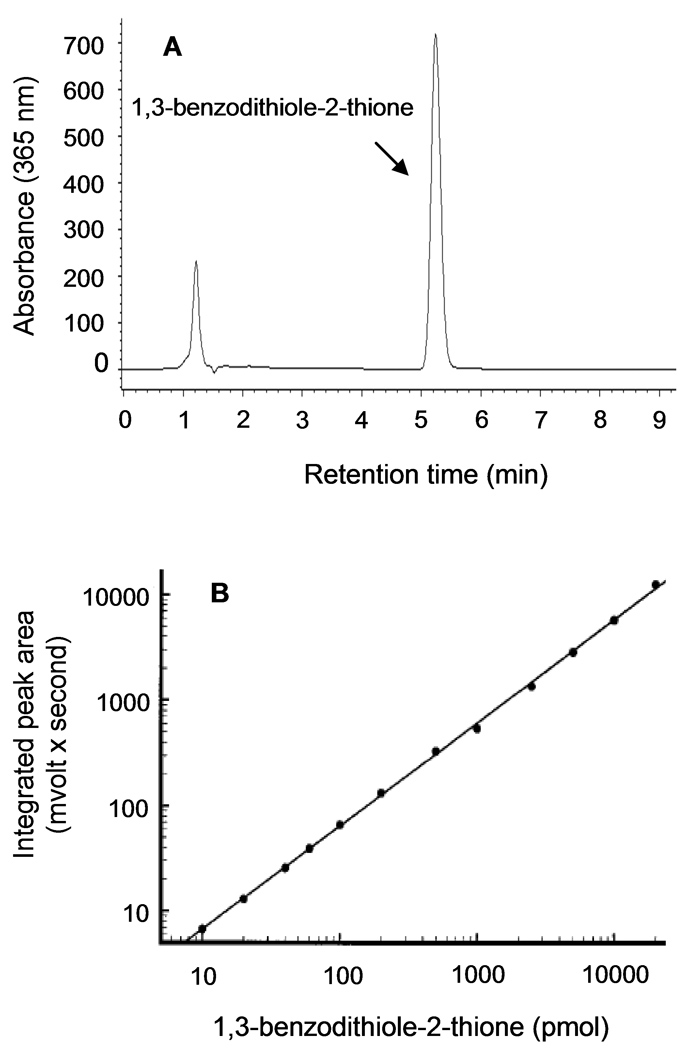

A typical 2-ml reaction consists of 1 ml methanol containing BDT, 0.5–1 ml 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 8.5), and the sample to be assayed. BDT is present in ≥100 fold excess over the ITC to be measured, typically at 4 mM. The mixture is kept in a tightly capped glass vial and is heated at 65 °C for 2 h (Zhang et al., 1992a). Although BDT was routinely distilled before use in our previous experiments, we later found that distillation was not necessary for commercial BDT at ≥90% purity. Direct spectrophotometric determination of the reacted solution at 365 nm allows measurement of as low as 1 nmol of ITC (Zhang et al., 1992a). Although this system is suitable for quantifying many ITCs and other compounds, certain modifications were later made. We showed that the sensitivity of detection could be lowered to 10 pmol by separating 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione from other substances in the reaction mixture by simple reverse phase HPLC and area integration of the product peak detected with a photodiode array detector (Figure 3B) (Zhang et al., 1996). Using an analytical C18 reverse phase column, with an isocratic mobile phase of 80% methanol and 20% water at a flow rate of 2 ml/min, 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione is eluted out at 5–6 min (Figure 3A) (Zhang et al., 1996). This approach also expanded the versatility of the assay, as samples with strong color (e.g., plant extracts or blood) could also be analyzed. Moreover, the detection sensitivity could be lowered at least another 10-fold by solid phase extraction of 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione via a small reverse phase Sep-Pak cartridge (Ye et al., 2002). The reaction volume may be reduced 10 fold, if sample availability is limited (Zhang and Talalay, 1998). For urine samples, the phosphate solution is replaced with 500 mM sodium borate buffer (pH 9.25), in order to maintain high pH of the reaction solution (Ye et al., 2002). Acetone, acetonitrile, dimethylsulfoxide, dimethylformamide or 2-propanol may be used to dissolve samples that are insoluble in methanol or water or to reduce the formation of precipitates in the reaction solution when protein-rich samples are used. These solvents may replace one-half or more of the methanol in the standard reaction solution (Chung et al., 1998; Ye et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 1996). With compounds which react slowly, the final concentration of BDT may be raised to 50 mM (Zhang and Talalay, 1998; Zhang et al., 1996). High protein levels in blood and tissue samples may hamper the assay, presumably through absorption of the relatively hydrophobic 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione by proteins in the reaction solution. We showed that this could be overcome by incubating the sample with 6% polyethylene glycol (MW 8000) or by filtration of the sample through a Centricon YM-30 filter, and assaying the supernatant/filtrate (Ye et al., 2002). It was reported that 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione could be fully extracted from the reaction solution with hexane, followed by evaporation of the extract to dryness by a Speed-Vac before HPLC analysis (Liebes et al., 2001). However, evaporation of the extract under high vacuum might cause loss of 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione (Ye et al., 2002). It is also important to note that formation of very high concentrations of 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione in the reaction solution should be avoided, as this may result in its precipitation or crystallization, although there was a linear response (over 3 orders of magnitude of concentration range) of the photodiode array detector to serial injections of this compound dissolved in methanol (Figure 3B) (Zhang et al., 1996). 1,3-Benzodithiole-2-thione is not commercially available, but a procedure to prepare it was previously described (Zhang et al., 1992a).

Figure 3.

Measurement of 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione by reverse phase HPLC. Samples were injected automatically onto a HPLC column, eluted isocratically with 80% methanol and 20% water at a flow rate of 2 ml/min. A, a typical chromatogram of a completed cyclocondensation reaction solution. B, a standard curve of 1,3-benzodithiole-2-thione measured by HPLC (Zhang et al., 1996).

The specificity of and potential false positives in the cyclocondensation assay

A wide variety of ITCs, both aliphatic and aromatic, were fully reactive with BDT under the assay conditions described above, but tert-butyl ITC and other tertiary ITCs were poorly reactive (Zhang et al., 1992a). Efforts to force the reaction by increasing the concentration of BDT to 50 mM or by prolonging the incubation period to 15 h at 65 °C led to only 20% reaction of tert-butyl ITC (Zhang et al., 1996). It is unclear whether the steric hindrance imposed by the tertiary carbon atom blocks access of the attacking thiols to the carbon of the –N=C=S group, or whether the multiple methyl groups reduced the electronegativity of the adjacent nitrogen and thus makes the departure of the free amine unfavorable. Fortunately, no tertiary ITC is known to occur in nature.

Sinigrin, the glucosinolate of AITC, was totally nonreactive under the assay condition (Zhang et al., 1992a), and there has been no report that any other glucosinolates could be detected by this assay. Besides ITCs, other products may also be generated from certain glucosinolates, including nitriles, thiocyanates or oxazolidinethiones (Pessina et al., 1990), but none of these compounds could be detected by the cyclocondensation assay. Other compounds that possess similar chemical structures such as cyanates and isocyanates did not react.

As discussed above, the dithiocarbamate metabolites of ITCs are fully reactive with BDT. However, certain dithiocarbamates that are not derived from ITCs and related compounds, including certain thiurams, metal-containing dithiocarbamates, substituted thioureas, xanthates and carbon disulfide are also reactive (Zhang et al., 1996). Some dithiocarbamates and thiurams are used as antioxidants and vulcanization accelerators for both natural and synthetic rubber. Thus, these compounds may be present at significant levels in a broad range of rubber products. For example, the total levels of dithiocarbamates and thiurams in natural and synthetic gloves as well as synthetic polymer gloves was found by the cyclocondensation assay to be as high as 43 µmol/g glove (our unpublished data). Thus, when handling the cyclocondensation assay, care is needed to avoid potential contamination by glove or blood-drawing equipment (e.g., stoppers of Vacutainers and rubber tips of syringe plungers). However, we found no dithiocarbamates and thiurams in vinyl gloves (our unpublished data). Carbon disulfide is a component of tobacco smoke and may be present at significant levels in the urine of cigarette smokers (Shapiro et al., 1998).

The advantages and limitations of the cyclocondensation assay

The cyclocondensation assay does not require prior modification of ITCs, unlike other methods that require either radiolabelling (Bollard et al., 1997; Brusewitz et al., 1977) or chemical derivatization of the compounds (Ji and Morris, 2003). It does not require highly sophisticated instruments and avoids potential under-detection which may occur with methods focused on specific ITCs or their metabolites, such as mass spectrometry-based methods. The dithiocarbamate metabolites of ITCs are unstable and can dissociate back to ITC (Conaway et al., 2001). Moreover, the side chain of a given ITC may be metabolized in vivo, as in the case of SF (Kassahun et al., 1997), leading to formation of potentially unknown dithiocarbamates. The cyclocondensation assay can overcome these problems, as it detects both ITCs and their dithiocarbamate metabolites. Moreover, because accumulating data have convincingly shown that ITC-derived dithiocarbamates serve as carriers of the ITCs (Bruggeman et al., 1986; Conaway et al., 2001) and the chemopreventive activities of these dithiocarbamates closely resemble those of their parent compounds (Chiao et al., 2002; Chung et al., 2000; Conaway et al., 2005; Jiao et al., 1997; Yang et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2005), measurement of the total level of ITC plus its dithiocarbamate metabolities in vivo by the cyclocondensation assay provides a full assessment of tissue exposure to the ITC.

However, this advantage of the cyclocondensation assay is also its limitation. Thus, it is not capable of discriminating each individual ITC or dithiocarbamate, as any reactive ITC or dithiocarbamate forms the identical cyclic product. While many population studies and a randomized clinical trial have shown that urinary level of ITC equivalents (total ITCs plus their dithiocarbamate metabolites, measured by the cyclocondensation assay), is inversely associated with the risk of various cancers (breast, colon, lung and stomach) (Fowke et al., 2003; London et al., 2000; Moy et al., 2009; Yang et al.) or carcinogen-induced DNA damage (Kensler et al., 2005), the identities of the ITCs and their metabolites measured in these studies were largely unknown. Moreover, care is needed to avoid potential false positive detection, since a number of other chemical entities can undergo the same reaction with BDT, as described above.

Measurement of ITC levels in urine and plasma

The cyclocondensation assay has been used to measure ITC equivalents in urine and plasma. Using AITC as an example, we showed that approximately 75% and 0.6% of a single oral dose of AITC to rats was detected as AITC equivalents in the first and second 24-h periods of urine after dosing (Munday et al., 2006), showing rapid AITC elimination via the urine. In previous studies using [14C]AITC, approximately 80% of the administered dose was recovered in the urine, as measured by radioactivity (Bollard et al., 1997; Ioannou et al., 1984). Thus, the cyclocondensation assay measured nearly all AITC and its metabolites in the urine. In humans, after a single 74 µmol oral dose of horseradish ITCs, the majority of which was AITC, 42% of the dose was recovered as ITC equivalents in the 10-h urine following dosing (Shapiro et al., 1998). Similar results were obtained with other ITCs. When rats were administered a single oral dose of broccoli sprout extract (BSE) which contains several alkyl ITCs (mainly SF), 70–79% and 1% of the ITC dose were detected by the cyclocondensation assay in the first and second 24-h periods of urine after dosing (Zhang et al., 2006), while another study showed that most was excreted in the first 12 h (Munday et al., 2008). In humans, after a single oral dose of BSE containing 200 µmol ITC, 58% of the ITC dose was detected as ITC equivalents in the 8-h urine after dosing (Ye et al., 2002). Moreover, subsequent studies showed that the percentage urinary recovery of ITC equivalents, remained virtually unchanged when the ITC dose delivered with BSE was increased from 10 to 250 µmol/kg in rats or 25 to 200 µmol per person (Shapiro et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2006). Likewise, the percentage urinary recovery of ITC equivalents remained unchanged when the ITC dose delivered with horseradish was increased from 12 to 74 µmol per person (Shapiro et al., 1998). These observations show the robustness of the mercapturic acid metabolic pathway and the urinary elimination process in handling ITCs. Interestingly, in rats given a single oral dose of 1-methylbutyl ITC or n-decyl ITC (25 µmol/kg), while their urinary elimination was also largely completed within 24 h, only 55% and 11% of the dose were recovered as ITC equivalents in the urine, respectively, and decreased to 34% and 7.2%, respectively, when the dose of each ITC was increased 10 fold (Munday et al., 2006). The reason for the relatively low percentages of urinary recovery for these compounds, compared with that of AITC and SF, is not known, but it is possible that high lipophilicity of these ITCs, n-decyl ITC in particular, might hinder gastrointestinal absorption.

The cyclocondensation assay has also been used to compare plasma levels of ITC equivalents with those in urine. Oral administration of AITC led to a dose-dependent increase in plasma levels of AITC equivalents in rats. Peak plasma levels of AITC equivalents of 1.5 and 23.4 µM were reached within 3 h of AITC dosing at 10 and 300 µmol/kg, followed by a rapid decline (half-life of ~3–6 h), whereas the average 6-h urinary concentrations of AITC equivalents were 0.23 and 9.94 mM, which were 150–425 fold higher than those in the plasma (Bhattacharya et al., 2010). Likewise, in rats receiving a single oral dose of BSE at 160 µmol ITC/kg, the peak plasma level of ITC equivalents (16.3 µM) was reached within 1 h, followed by a rapid decline (half-life of 8.4 h), whereas the average 1-h and 24-h urinary concentrations of ITC equivalent were 1.34 and 2.41 mM, which are 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than the peak plasma concentration (Munday et al., 2008). The cyclocondensation assay has also made it possible to show that rapid absorption and plasma clearance of ITCs as well as dramatic difference in urinary and plasma concentrations of ITC equivalents also occur in humans. For example, in volunteers administered a single oral dose of BSE (200 µmol ITC/person), plasma levels of ITC equivalents of 0.94–2.27 µM peaked at 1 h and declined rapidly thereafter (half-life of 1.8 h), whereas the average 8-h urinary concentration of ITC equivalents was 232 µM (assuming 0.5 liter of urine production), which is 102–247 fold higher than the peak plasma concentrations (Ye et al., 2002). These observations strongly indicate that dietary ITCs are preferentially delivered to bladder tissue through urinary excretion.

Measurement of cell and tissue exposure to ITC

The cyclocondensation assay has been used to measure ITC uptake by cells and tissues. In murine hepatoma Hepa 1c1c7 cells exposed to [14C]PEITC, 80–90% of the ITC that was absorbed by the cells was detected by the cyclocondensation assay, and in the case of fluorescein ITC, nearly all of its cellular uptake was detected by the cyclocondensation assay (Zhang and Talalay, 1998). These and subsequent studies, all relying on the cyclocondensation assay, have led to the discovery of rapid cellular uptake and elimination of ITCs in human and animal cells (Zhang, 2000; Zhang, 2001; Zhang and Callaway, 2002; Zhang and Talalay, 1998). Briefly, ITCs appear to penetrate cells by diffusion and upon entering the cell are rapidly conjugated with intracellular thiols. GSH which is the most abundant intracellular thiol is the major driving force for ITC accumulation. Thus, ITCs are accumulated mainly as GSH conjugates. The peak intracellular ITC accumulation is reached within 0.5–3 h and reaches100–200 fold over the extracellular concentration. However, intracellularly accumulated GSH conjugates of ITCs, perhaps other conjugates as well, are also rapidly exported by membrane transporters, including multidrug resistance associated protein-1 (MRP-1) (Callaway et al., 2004; Zhang and Callaway, 2002). For example, 50% of accumulated SF in human prostate cancer LNCaP cells was lost in 1 h, and intracellular accumulation of SF could only be maintained when there was a continuous presence of SF in the extracellular space to allow continuous cellular uptake of SF to offset the rapid export of conjugated SF (Zhang and Callaway, 2002).

The cyclocondensation assay has also been used to measure ITC levels in normal and tumor tissues. In one study, in which rats were given a single oral dose of ITC (160 µmol/kg) using BSE, and tissue levels of ITC equivalents in the liver and bladder at different time points were compared, the level of ITC equivalents in the bladder tissue was significantly higher than that in the liver (Munday et al., 2008). In another study, rats bearing both orthotopic bladder tumor and subcutaneous tumor, both of which developed from the same bladder cancer cells, were given a single oral dose of AITC at 300 µmol/kg. Tissue levels of AITC equivalents in the orthotopic bladder tumors at 3 h and 6 h after AITC dosing were 720- and 986-fold higher than that in the subcutaneous tumors at the same time points (Bhattacharya et al., 2010). These findings are consistent with other data showing that ITCs are preferentially delivered to bladder through urinary excretion and suggest that ITC may be particularly useful for bladder cancer prevention.

Measurement of ITC in plants and the bioavailability of plant ITC

The cyclocondensation assay has been used to measure total ITC levels in a variety of vegetables. Fresh or cooked vegetables were prepared as aqueous extracts and were either directly analyzed by the cyclocondensation assay or first treated with exogenous myrosinase to fully hydrolyze glucosinolates (Jiao et al., 1998; Shapiro et al., 1998). Important information has been obtained from these studies. 1. Total ITC levels in vegetable extracts after myrosinase treatment increased up to 38 fold, consistent with the notion that ITCs are stored as glucosinolates in plants and suggesting that endogenous myrosinase in these plants, if present, is inadequate for full hydrolysis of glucosinolates. 2. Total ITC levels in 11 cruciferous vegetables assayed varied by nearly 16 fold, with the highest level detected in broccoli (0.8 µmol/g fresh weight) and the lowest detected in bok choi (0.05 µmol/g fresh weight). 3. None of the 10 non-cruciferous vegetables, including lettuce, spinach, carrots, tomatoes and others, contained any detectable ITC, consistent with the knowledge that cruciferous vegetables are the primary plant source of these compounds. Although the cyclocondensation assay does not identify the specific ITCs in vegetable extracts, and mass spectrometry-based methods may be employed to gain such information, it should be cautioned that ITCs in the extracts may exist in part as conjugates of GSH or other thiols (Gasper et al., 2005).

The cyclocondensation assay has also been used to investigate the bioavailability of ITC from cruciferous vegetables. To compare ITC bioavailability from fresh and steamed vegetables (endogenous myrosinase is inactivated in the latter case), human volunteers consumed 200 g fresh or steamed broccoli, followed by measurement of urinary levels of ITC equivalents. While total ITC contents in the fresh broccoli and steamed broccoli, measured after their aqueous extracts were treated with exogenous myrosinase, were almost identical (1.1 versus 1.0 µmol/g wet weight), the average 24-h urinary recovery of ITC equivalent was 32% and 10% of the ingested dose, respectively (Conaway et al., 2000). Thus, ITC bioavailability from fresh broccoli was more than three times higher than that from steamed broccoli. In another study, where 300 g watercress was cooked in boiling water for 3 min (to inactivate endogenous myrosinase) before being consumed by volunteers, the 24-h urinary recovery as ITC equivalents was 1.2–7.3% of the dose (Getahun and Chung, 1999). In contrast, the total 24-h urinary recovery as ITC equivalents was 17.2–77.7% of ingested dose when 150 g of uncooked watercress was ingested. Likewise, when human volunteers consumed BSE containing only ITCs (glucosinolates were hydrolyzed by myrosinase) or only glucosinolates (myrosinase was heat-inactivated), the 72-h cumulative urinary excretion of ITC equivalents was 80% and 12% of the dose, respectively (Shapiro et al., 2001). These studies clearly show that vegetables whose myrosinase is functional provide much more ITC than those without myrosinase. Moreover, the cyclocondensation assay has also made it possible to better understand the role of myrosinase in the intestinal microflora in the hydrolysis of glucosinolates. When the population of microflora was reduced by a combination of mechanical cleansing and oral antibiotics, there was a reduction in 72-h urinary recovery as ITC equivalents from 11.3% (pretreatment) to 1.3% (post-treatment), following consumption of 100 µmol of broccoli sprout glucosinolates (containing no myrosinase) (Shapiro et al., 1998). In another study involving 100 volunteers who consumed BSE (400 µmol glucosinolates, myrosinase inactivated), there was high inter-individual variability in urinary recovery as ITC equivalents in 12-h urine, ranging from 1% to 45% of the administered dose (Kensler et al., 2005). In contrast, in volunteers administered BSE (only ITCs, no glucosinolates), the intra- and inter-subject variation in urinary excretion of ITC equivalents was very small (coefficient of variation, 9%) (Shapiro et al., 2001). These findings indicate a wide inter-individual variability of the activity of intestinal microbial myrosinase. Moreover, the cyclocondensation assay also permitted investigation of the effect of vegetable-eating habit on ITC availability. In a study where each volunteer was asked to either swallow without chewing or chew thoroughly before swallowing 12 g fresh broccoli sprouts containing 109 µmol of glucosinolate/ITC, chewing and not chewing the sprouts led to 39% and 26% recovery as ITC equivalents in 24 h urine, respectively (Shapiro et al., 2001).

Concluding remarks

The 1,2-benzenedithiole-based cyclocondensation assay for measurement of ITCs and their metabolites is simple, generic, sensitive, quantitative and versatile. This method has been widely used and has allowed numerous ITC studies to be carried out. Many important findings have been made from these studies. This method will undoubtedly continue to facilitate research on the nutritional and chemopreventive importance of ITCs.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Dr. Rex Munday at AgResearh New Zealand for critical reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions. This work was supported by a grant from National Cancer Institute (R01CA124627)

References

- Bhattacharya A, Tang L, Li Y, Geng F, Paonessa JD, Chen SC, Wong MK, Zhang Y. Inhibition of bladder cancer development by allyl isothiocyanate. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:281–286. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollard M, Stribbling S, Mitchell S, Caldwell J. The disposition of allyl isothiocyanate in the rat and mouse. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1997;35:933–943. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(97)00103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman IM, Temmink JH, van Bladeren PJ. Glutathione- and cysteine-mediated cytotoxicity of allyl and benzyl isothiocyanate. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1986;83:349–359. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(86)90312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusewitz G, Cameron BD, Chasseaud LF, Gorler K, Hawkins DR, Koch H, Mennicke WH. The metabolism of benzyl isothiocyanate and its cysteine conjugate. Biochem. J. 1977;162:99–107. doi: 10.1042/bj1620099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway EC, Zhang Y, Chew W, Chow HH. Cellular accumulation of dietary anticarcinogenic isothiocyanates is followed by transporter-mediated export as dithiocarbamates. Cancer Lett. 2004;204:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao JW, Chung FL, Kancherla R, Ahmed T, Mittelman A, Conaway CC. Sulforaphane and its metabolite mediate growth arrest and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2002;20:631–636. doi: 10.3892/ijo.20.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho CG, Posner GH. Alkyl and aryl isothiocyanates as masked primary amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:3599–3602. [Google Scholar]

- Chung FL, Conaway CC, Rao CV, Reddy BS. Chemoprevention of colonic aberrant crypt foci in Fischer rats by sulforaphane and phenethyl isothiocyanate. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2287–2291. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.12.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung FL, Jiao D, Getahun SM, Yu MC. A urinary biomarker for uptake of dietary isothiocyanates in humans. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung FL, Morse MA, Eklind KI, Lewis J. Quantitation of human uptake of the anticarcinogen phenethyl isothiocyanate after a watercress meal. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1992;1:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway CC, Getahun SM, Liebes LL, Pusateri DJ, Topham DK, Botero-Omary M, Chung FL. Disposition of glucosinolates and sulforaphane in humans after ingestion of steamed and fresh broccoli. Nutr. Cancer. 2000;38:168–178. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC382_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway CC, Krzeminski J, Amin S, Chung FL. Decomposition rates of isothiocyanate conjugates determine their activity as inhibitors of cytochrome p450 enzymes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001;14:1170–1176. doi: 10.1021/tx010029w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway CC, Wang CX, Pittman B, Yang YM, Schwartz JE, Tian D, McIntee EJ, Hecht SS, Chung FL. Phenethyl isothiocyanate and sulforaphane and their N-acetylcysteine conjugates inhibit malignant progression of lung adenomas induced by tobacco carcinogens in A/J mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8548–8557. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman P. On the mechanism of the phenyl isothiocyanate degradation of peptides. Adta Chemica Scandinavica. 1956;10:761–768. [Google Scholar]

- Egner PA, Kensler TW, Chen JG, Gange SJ, Groopman JD, Friesen MD. Quantification of sulforaphane mercapturic acid pathway conjugates in human urine by high-performance liquid chromatography and isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008;21:1991–1996. doi: 10.1021/tx800210k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian J, Viola H, Mayer R. Quantitative beschreibung der UV-S-absorptionen einfacher thiocarbonylverbindungen. Tetrahedron. 1967;23:4323–4329. [Google Scholar]

- Fahey JW, Zalcmann AT, Talalay P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochem. 2001;56:5–51. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey JW, Zhang Y, Talalay P. Broccoli sprouts: an exceptionally rich source of inducers of enzymes that protect against chemical carcinogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:10367–10372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowke JH, Chung FL, Jin F, Qi D, Cai Q, Conaway C, Cheng JR, Shu XO, Gao YT, Zheng W. Urinary isothiocyanate levels, brassica, and human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3980–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasper AV, Al-Janobi A, Smith JA, Bacon JR, Fortun P, Atherton C, Taylor MA, Hawkey CJ, Barrett DA, Mithen RF. Glutathione S-transferase M1 polymorphism and metabolism of sulforaphane from standard and high-glucosinolate broccoli. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;82:1283–1291. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getahun SM, Chung FL. Conversion of glucosinolates to isothiocyanates in humans after ingestion of cooked watercress. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:447–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil V, Macleod AJ. Benylglucosinolate degradation in Lepidium sativum: effects of plant age and time of autolysis. Phytochem. 1980;19:1365–1368. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht SS. Chemoprevention of cancer by isothiocyanates, modifiers of carcinogen metabolism. J. Nutr. 1999;129:768S–774S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.768S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou YM, Burka LT, Matthews HB. Allyl isothiocyanate: comparative disposition in rats and mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1984;75:173–181. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y, Morris ME. Determination of phenethyl isothiocyanate in human plasma and urine by ammonia derivatization and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2003;323:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao D, Ho CT, Foiles P, Chung FL. Identification and quantification of the N-acetylcysteine conjugate of allyl isothiocyanate in human urine after ingestion of mustard. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao D, Smith TJ, Yang CS, Pittman B, Desai D, Amin S, Chung FL. Chemopreventive activity of thiol conjugates of isothiocyanates for lung tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:2143–2147. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.11.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao D, Yu MC, Hankin JH, Low SH, Chung FL. Total isothiocyanate contents in cooked vegetables frequently consumed in Singapore. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:1055–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Kassahun K, Davis M, Hu P, Martin B, Baillie T. Biotransformation of the naturally occurring isothiocyanate sulforaphane in the rat: identification of phase I metabolites and glutathione conjugates. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997;10:1228–1233. doi: 10.1021/tx970080t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensler TW, Chen JG, Egner PA, Fahey JW, Jacobson LP, Stephenson KK, Ye L, Coady JL, Wang JB, Wu Y, Sun Y, Zhang QN, Zhang BC, Zhu YR, Qian GS, Carmella SG, Hecht SS, Benning L, Gange SJ, Groopman JD, Talalay P. Effects of glucosinolate-rich broccoli sprouts on urinary levels of aflatoxin-DNA adducts and phenanthrene tetraols in a randomized clinical trial in He Zuo township, Qidong, People's Republic of China. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2605–2613. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebes L, Conaway CC, Hochster H, Mendoza S, Hecht SS, Crowell J, Chung FL. High-performance liquid chromatography-based determination of total isothiocyanate levels in human plasma: application to studies with 2-phenethyl isothiocyanate. Anal. Biochem. 2001;291:279–289. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London SJ, Yuan JM, Chung FL, Gao YT, Coetzee GA, Ross RK, Yu MC. Isothiocyanates, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms, and lung-cancer risk: a prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Lancet. 2000;356:724–729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy KA, Yuan JM, Chung FL, Wang XL, Van Den, Berg D, Wang R, Gao YT, Yu MC. Isothiocyanates, glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk: a prospective study of men in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;125:2652–2659. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukerjee AK, Ashare R. Isothiocyanates in the chemistry of heterocycles. Chemical Reviews. 1991;91:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Munday R, Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Munday CM, Paonessa JD, Tang L, Munday JS, Lister C, Wilson P, Fahey JW, Davis W, Zhang Y. Inhibition of urinary bladder carcinogenesis by broccoli sprouts. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1593–1600. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday R, Zhang Y, Fahey JW, Jobson HE, Munday CM, Li J, Stephenson KK. Evaluation of isothiocyanates as potent inducers of carcinogen-detoxifying enzymes in the urinary bladder: critical nature of in vivo bioassay. Nutr. Cancer. 2006;54:223–231. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5402_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessina A, Thomas RM, Palmieri S, Luisi PL. An improved method for the purification of myrosinase and its physicochemical characterization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;280:383–389. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90346-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P. Human metabolism and excretion of cancer chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of cruciferous vegetables. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1091–1100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro TA, Fahey JW, Wade KL, Stephenson KK, Talalay P. Chemoprotective glucosinolates and isothiocyanates of broccoli sprouts: metabolism and excretion in humans. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:501–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu Y, Hirata K, Suzuki K, Iida K, Ueta T, Kamata K. Determination of isothiocyanates and related compounds in mustard extract and horseradish extract used as natural food additives. Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. 2002;43:10–17. doi: 10.3358/shokueishi.43.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G, Gao YT, Shu XO, Cai Q, Li GL, Li HL, Ji BT, Rothman N, Dyba M, Xiang YB, Chung FL, Chow WH, Zheng W. Isothiocyanate exposure, glutathione S-transferase polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;91:704–711. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Conaway CC, Chiao JW, Wang CX, Amin S, Whysner J, Dai W, Reinhardt J, Chung FL. Inhibition of benzo(a)pyrene-induced lung tumorigenesis in A/J mice by dietary N-acetylcysteine conjugates of benzyl and phenethyl isothiocyanates during the postinitiation phase is associated with activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases and p53 activity and induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Jhanwar-Uniyal M, Schwartz J, Conaway CC, Halicka HD, Traganos F, Chung FL. N-acetylcysteine conjugate of phenethyl isothiocyanate enhances apoptosis in growth-stimulated human lung cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8538–8547. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Wade KL, Zhang Y, Shapiro TA, Talalay P. Quantitative determination of dithiocarbamates in human plasma, serum, erythrocytes and urine: pharmacokinetics of broccoli sprout isothiocyanates in humans. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2002;316:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Allyl isothiocyanate as a cancer chemopreventive phytochemical. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2010;54:127–135. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Role of glutathione in the accumulation of anticarcinogenic isothiocyanates and their glutathione conjugates by murine hepatoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Molecular mechanism of rapid cellular accumulation of anticarcinogenic isothiocyanates. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:425–431. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Cancer-preventive isothiocyanates: measurement of human exposure and mechanism of action. Mutat. Res. 2004;555:173–190. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Callaway EC. High cellular accumulation of sulphoraphane, a dietary anticarcinogen, is followed by rapid transporter-mediated export as a glutathione conjugate. Biochem. J. 2002;364:301–307. doi: 10.1042/bj3640301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cho CG, Posner GH, Talalay P. Spectroscopic quantitation of organic isothiocyanates by cyclocondensation with vicinal dithiols. Anal. Biochem. 1992a;205:100–107. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90585-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Munday R, Jobson HE, Munday CM, Lister C, Wilson P, Fahey JW, Mhawech-Fauceglia P. Induction of GST and NQO1 in cultured bladder cells and in the urinary bladders of rats by an extract of broccoli (Brassica oleracea italica) sprouts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:9370–9376. doi: 10.1021/jf062109h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Talalay P. Anticarcinogenic activities of organic isothiocyanates: chemistry and mechanisms. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1976s–1981s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Talalay P. Mechanism of differential potencies of isothiocyanates as inducers of anticarcinogenic Phase 2 enzymes. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4632–4639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Talalay P, Cho CG, Posner GH. A major inducer of anticarcinogenic protective enzymes from broccoli: isolation and elucidation of structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992b;89:2399–2403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Tang L. Discovery and development of sulforaphane as a cancer chemopreventive phytochemical. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007;28:1343–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wade KL, Prestera T, Talalay P. Quantitative determination of isothiocyanates, dithiocarbamates, carbon disulfide, and related thiocarbonyl compounds by cyclocondensation with 1,2-benzenedithiol. Anal. Biochem. 1996;239:160–167. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]