Summary

Background and objectives

Clinical practice guidelines recommend that body mass index (BMI) in children with CKD be expressed relative to height-age (BMI-height-age-z) rather than chronologic age (BMI-age-z) to account for delayed growth and sexual maturation. This approach has not been validated. This study sought to (1) compare children who have CKD with healthy children regarding the relationships between BMI-age-z and each of relative lean mass (LM) and adiposity and (2) determine whether BMI-height-age-z reflects relative LM and adiposity in CKD in the same way that BMI-age-z does in healthy children.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In a cross-sectional study, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry was used to assess whole-body fat mass (FM) and LM in 143 participants with CKD and 958 healthy participants (age, 5–21 years); FM and LM were expressed as sex-specific Z-scores relative to height (LM-height-z, FM-height-z), with healthy participants as the reference. BMI-age-z and BMI-height-age-z were determined using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference data.

Results

Compared with healthy children of the same sex, age, race, and BMI-age-z, LM-height-z was significantly higher in males with all CKD stages (by 0.41–0.43 SDs) and in females with mild to moderate CKD (by 0.38 SD); FM-height-z was significantly higher in both males (by 0.26 SD) and females (by 0.52 SD) with severe CKD. Underestimation of relative LM and adiposity was improved by expressing BMI relative to height-age.

Conclusions

In children with CKD, BMI-height-age-z reflects relative LM and adiposity in the same way that BMI-age-z does in healthy children.

Children with CKD are at risk for growth retardation and muscle wasting (1–3). Therefore, clinical practice guidelines recommend regular assessment of growth and nutritional status, including determination of body mass index (BMI), a measure of weight relative to height (4). Although BMI does not provide direct information on body composition, it is generally accepted as a reliable method of assessing adiposity (fat mass [FM] relative to height) in healthy children (5,6), particularly at the upper end of the BMI range; at the lower end of the BMI range, BMI better reflects lean mass (LM) relative to height (7–10). In clinical practice, BMI is often calculated in children with CKD with a view to identifying underweight and LM wasting.

In children, normal BMI changes with age due to changes in height, body proportions, and body composition (8,11). Therefore, BMI in children is expressed as a percentile or Z-score relative to age (BMI-age-z). In healthy children, in whom age, height, and sexual maturation are highly correlated, this approach works well; age provides a reasonable surrogate for both height and stage of sexual maturation (4). However, in CKD the normal relations between age, height, and sexual maturation are commonly disturbed; BMI-age-z may not be interpretable in the same way in children with CKD as it is in healthy children (12). For this reason, current clinical practice guidelines recommend that BMI be expressed relative to height-age rather than relative to age (4). Height-age is the age at which a child would be of average height (50th percentile) for age. The rationale for this recommendation is that short, relatively sexually immature children with CKD may be more appropriately compared with younger, similarly shorter and less mature healthy children than with children of the same age. Although this seems logical, the approach has never been validated and remains controversial.

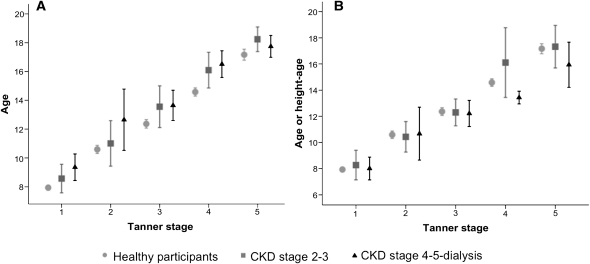

We hypothesized that expressing BMI relative to chronologic age in children with CKD would result in underestimation of relative LM and adiposity, given that LM and adiposity increase with maturation and that children with CKD are less mature than age-matched healthy children. We further hypothesized that this underestimation would be improved by expressing BMI relative to height-age. The aims of this cross-sectional observational study were two-fold. First, we sought to identify differences in the age distributions between healthy and CKD participants within each stage of pubertal development (Tanner stage) and to determine whether height-age corresponds better than chronologic age to the expected age distribution within each Tanner stage in children with CKD. Second, we aimed to determine whether the relations between BMI-age-z and each of relative LM and adiposity differ in children with CKD compared with healthy children and, if so, whether BMI expressed relative to height-age (BMI-height-age-z) in CKD can be interpreted in the same way that BMI-age-z is interpreted in healthy children.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The same participants presented here were previously described in a study that compared total and regional body composition between healthy children and children with CKD (1). Briefly, children and adolescents with CKD (estimated GFR < 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 [13]), between 5 and 21 years of age, were recruited from the nephrology clinics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Healthy children and adolescents were recruited from general pediatric clinics in Philadelphia and Cincinnati and the surrounding communities. Individuals with chronic medical conditions potentially affecting growth, pubertal development, or body composition were excluded. Obesity was not an exclusion criterion. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both sites, and written informed consent was obtained.

Disease and Treatment Characteristics

Medical charts were reviewed to obtain disease and treatment characteristics. The GFR was estimated from serum creatinine for all patients with CKD using the updated Schwartz equation (14) and was used to classify patients with CKD into Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative CKD stages (15). CKD stages 2 and 3 were combined (mild to moderate), as were CKD stages 4, 5, and dialysis (severe).

Anthropometry and Tanner Staging

Height was measured with a wall-mounted stadiometer (Holtain, Crosswell, Wales) and weight with a digital scale (Scaletronix, White Plains, NJ). BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Sex-specific height-for-age Z-scores and BMI-age-z were calculated for all participants using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) centile curves as the reference; these curves were also used to determine height-age (16) and to calculate BMI-height-age-z for patients with CKD. Pubertal status was determined by self-assessment and classified according to the method of Tanner (17,18). Participants were asked to categorize their race according to the National Institutes of Health categories.

Body Composition

Whole-body FM and LM (excluding the head) were assessed in all participants with whole-body dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using a Delphi or Discovery densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA) with a fan beam in the array mode, using standard positioning techniques. Scans were obtained when dialysis participants were at their estimated dry weight. DXA is a precise (coefficient of variation, 1%–4%) (19) and widely used method for describing age-, sex-, race-, and pubertal maturation–related variability in body composition (20–23). All scans were analyzed at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia with Hologic software version 12.4. The calibration of the scanners at each site was checked daily using a hydroxyapatite spine phantom and weekly with a whole-body phantom. The intra-individual coefficients of variation of DXA for whole-body LM and FM are 1.0% and 2.1%, respectively (24).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using Stata software, version 10.0 (College Station, TX), and LMS Chartmaker Pro (Institute for Child Health, London, United Kingdom). Two-sided tests were used throughout, and a P value less than 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference. Within each Tanner stage, mean age and height-age for each CKD group were compared with mean age for healthy participants using a t test. Mean height was also compared between each CKD group and healthy participants within each Tanner stage using a t test (with unequal variance).

Relative LM and Adiposity Assessment.

In the absence of accepted gold standard methods of assessing relative LM or adiposity, we quantified relative LM and adiposity by expressing each of whole-body LM and whole-body FM as Z-scores relative to height, as previously described (1). Briefly, we used the LMS method (25–27) and data from the healthy participants to generate sex- and race-specific LM-for-height and FM-for-height centile curves; then, a LM-for-height Z-score (LM-height-z) and a FM-for-height Z-score (FM-height-z) was calculated for each CKD and healthy participant.

Assessing BMI-Age-Z as a Measure of Relative LM and Adiposity in CKD.

If BMI-age-z reflects relative LM among children with CKD in the same way that it does among healthy children, the relationship between BMI-age-z and LM-height-z should be the same for children with CKD as for healthy children. To compare this relationship between patients with CKD and healthy participants, we first built sex-specific multivariable linear regression equations to predict LM-height-z from BMI-age-z, age, race, and study site among the healthy participants. These equations were then used to predict LM-height-z from BMI-age-z, age, race, and study site for CKD participants. The difference between measured LM-height-z and LM-height-z predicted from BMI-age-z among patients with CKD was determined; this difference indicated how much the LM-height-z was overestimated (negative values) or underestimated (positive values) from BMI-age-z. Then the same regression equations were used to predict LM-height-z for patients with CKD, but this time BMI-height-age-z was substituted for BMI-age-z in the equations. The agreement between measured LM-height-z and LM-height-z predicted from BMI-height-age-z was determined. The same approach was taken to determine the relation between BMI-age-z and FM-height-z.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The characteristics of the 958 healthy participants and 143 participants with CKD are summarized in Table 1. Among the patients with CKD, 64 were in CKD stages 2–3 and 79 were in CKD stages 4–5–dialysis (20 hemodialysis, 14 peritoneal dialysis). As previously reported, patients with CKD 2–3 and CKD 4–5–dialysis had significantly lower height-for-age z-scores than healthy children (both P<0.001) (1). Disease characteristics for the CKD participants are presented elsewhere (1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variable | Healthy | CKD Stage 2–3 | CKD Stage 4–5–Dialysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| Participants (n) | 459 | 499 | 35 | 29 | 52 | 27 |

| Age (yr) | 11.9±4.0 | 11.9±4.0 | 12.4±4.2 | 14.8±3.8 | 13.9±3.8 | 14.9±3.5 |

| Black, n (%) | 191 (42) | 200 (40) | 7 (20) | 7 (24) | 16 (31) | 912 (33) |

| Tanner stage (IQR) | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (1, 4) | 2 (1, 4) | 4 (2, 5) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (2, 5) |

| Height-age | 12.2±4.1 | 12.2±4.7 | 12.1±4.6 | 14.0±4.2 | 12.4±3.8 | 11.8±2.8 |

| Height-for-age Z-score | 0.24±0.91 | 0.32±0.92 | −0.19±1.02 | −0.28±1.32 | −0.92±1.26 | −1.23±1.08 |

| BMI-age-z | 0.35±1.04 | 0.35±0.99 | 0.40±1.06 | 0.34±1.20 | 0.39±1.27 | −0.05±1.16 |

| BMI-height-age-z | 0.28±1.03 | 0.24±1.03 | 0.42±1.09 | 0.51±1.17 | 0.67±1.19 | 0.47±1.10 |

| FM-height-z | 0.02±1.01 | 0.008±1.01 | 0.03±1.31 | 0.32±1.33 | 0.36±1.26 | 0.30±1.20 |

| LM-height-z | 0.005±1.0 | −0.02±1.0 | 0.52±1.25 | 0.39±1.39 | 0.50±1.26 | −0.06±1.19 |

| Current growth hormone use, n (%) | — | — | 3 (9) | 0 (0) | 8 (15) | 2 (7) |

| Ever growth hormone use, n (%) | — | — | 4 (11) | 1 (3) | 20 (38) | 5 (19) |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD except for number of participants and for Tanner stage, which is expressed as a median with interquartile range. IQR, interquartile range.

Height, Age, and Height-Age Distributions by Tanner Stage

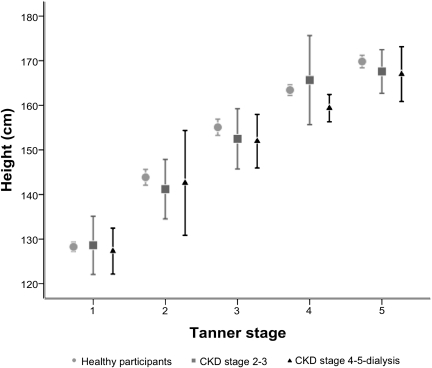

As shown in Figure 1, patients with CKD were slightly shorter than healthy children within the same Tanner stage for most Tanner stages; however, these differences were not statistically significant. Patients with CKD were significantly older than healthy participants in the same Tanner stage (Figure 2A). In contrast, the height-age distributions of patients with CKD were not significantly different from the chronologic age distributions in healthy participants of the same Tanner stage (Figure 2B). The same results were observed in analyses stratified by sex, but numbers in each sex-Tanner stage category were very small, so the sexes were combined.

Figure 1.

Mean height (with 95% confidence intervals) by Tanner stage among healthy participants and those with CKD.

Figure 2.

Comparison of age or height age by Tanner stage between CKD and healthy participants. (A) Mean age (with 95% confidence intervals) within each Tanner stage for healthy participants compared with that among CKD participants. (B) Mean age (with 95% confidence intervals) within each Tanner stage for healthy participants compared with mean height-age (with 95% confidence intervals) for CKD participants.

Relationship between BMI-Age-Z and Relative LM

Patients with CKD had higher LM-height-z than healthy participants of the same BMI-age-z; underestimation of LM-height-z from BMI-age-z was more marked in males than in females. As shown on the left side of Table 2, among males, measured LM-height-z values were 0.43 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13–0.74) SD higher for patients with CKD stage 2–3 (P=0.001) and 0.41 (95% CI, 0.17–0.65) SD higher for those with CKD stage 4–5–dialysis (P<0.001) than LM-height-z predicted from BMI-age-z. Among females, measured LM-height-z was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.01–.75) SD higher for patients with CKD stage 2–3 than predicted LM-height-z; measured LM-height-z was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.10–0.55) SD higher for female patients with CKD stage 4–5–dialysis than LM-height-z predicted from BMI-age-z, but this finding was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of BMI-age-z with BMI-height-age-z as predictors of adiposity and relative lean mass in CKD

| CKD Stage | Measured Minus Predicted LM-Height-Z | Measured Minus Predicted FM-Height-Z | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||

| Predicted from BMI-age-z | Predicted from BMI-height-age-z | Predicted from BMI-age-z | Predicted from BMI-height-age-z | Predicted from BMI-age-z | Predicted from BMI-height-age-z | Predicted from BMI-age-z | Predicted from BMI-height-age-z | |

| CKD stage 2–3 | 0.43 (0.13–0.74) | 0.41 (0.13–0.70) | 0.38 (0.01–0.75) | 0.25 (−0.11 to 0.60) | −0.14 (−0.40 to 0.13) | −0.16 (−0.43 to 0.12) | 0.16 (−0.14 to 0.46) | 0.01 (−0.27 to 0.30) |

| CKD stage 4–5–dialysis | 0.41 (0.17–0.65) | 0.20 (−0.03 to 0.42) | 0.27 (−0.01 to 0.55) | −0.15 (−0.43 to 0.13) | 0.26 (0.05–0.46) | 0.03 (−0.18 to 0.24) | 0.50 (0.24–0.76) | 0.05 (−0.16 to 0.27) |

Each of LM-height-z and FM-height-z were predicted first from BMI-age-z, age, race, and study site. The predicted LM-height-z and FM-height-z were each subtracted from the corresponding measured values; the mean differences with 95% confidence intervals are presented. Then, BMI-height-age-z was substituted for BMI-age-z in the predictive equations to predict each of LM-height-z and FM-height-z. The BMI-height-age-z predicted LM-height-z and FM-height-z were each subtracted from the corresponding measured values; the mean differences with 95% confidence intervals are presented. Confidence intervals that do not include zero indicate statistically significant differences. LM, lean mass; FM, fat mass; BMI, body mass index.

The relationship between BMI-height-age-z and LM-height-z in patients with CKD was similar to that between BMI-age-z and LM-height-z in healthy participants. As shown in Table 2, when we predicted LM-height-z for CKD participants by substituting BMI-height-age-z for BMI-age-z in the predictive equations derived using the healthy participants, the LM-height-z estimation was improved for males in the CKD stage 4–5–dialysis group and for females in the CKD stage 2–3 group. For males in the CKD stage 4–5–dialysis group, LM-height-z predicted from BMI-height-age-z was not significantly different from measured LM-height-z (difference, 0.20 [95% CI, −0.03 to 0.42] SD). For females in the CKD stage 2–3 group, LM-height-z predicted from BMI-height-age-z was also not significantly different from measured LM-height-z (difference, 0.25 [95% CI, −0.11 to 0.60] SD). LM-height-z was still underestimated to the same degree in males with CKD stage 2–3. In females in the CKD stage 4–5–dialysis group, the difference between measured LM-height-z and LM-height-z predicted from BMI-height-age-z was somewhat smaller than the difference between measured LM-height-z and LM-height-z predicted from BMI-age-z (difference, −0.15 [95% CI, −0.43 to 0.13] SD), but neither difference was statistically significant.

Relationship between BMI-Age-Z and Adiposity

Overall, the relationships observed between BMI-age-z and adiposity were similar to those observed for relative LM. As shown on the right side of Table 2, patients with CKD had higher FM-height-z than healthy participants with the same BMI-age-z; underestimation of adiposity from BMI-age-z among children with CKD was greater in females than males and was greater with more severe CKD. When the equation derived using the healthy participants was used to predict FM-height-z from BMI-age-z among patients with CKD, predicted FM-height-z was not significantly different from measured FM-height-z for female patients with CKD stage 2–3 (FM-height-z difference, 0.16 [95% CI, −0.14 to 0.46] SD) but was 0.50 [95% CI, 0.24–0.76] SD higher for patients with CKD stage 4–5–dialysis. Similarly, in male patients with CKD stage 2–3, FM-height-z predicted from BMI-age-z did not differ significantly from measured FM-height-z (FM-height-z difference, −0.14 [95% CI, −0.40 to 0.13] SD) but was 0.26 [95% CI, 0.05–0.46] SD higher for male patients with CKD stage 4–5–dialysis.

The relationship between FM-height-z and BMI-height-age-z in patients with CKD mirrored the relation between FM-height-z and BMI-age-z in healthy participants. As shown on the right side of Table 2, when BMI-height-age-z was substituted for BMI-age-z in the predictive equation for patients with CKD, the differences between predicted and measured FM-height-z were not significantly different from zero for males or females in either CKD group.

Effect of Different Reference Populations for BMI Z-Scores and LM and FM Z-Scores

The BMI Z-scores were generated using the CDC reference population, whereas LM-height-z and FM-height-z were generated using data from the healthy participants of this study. Healthy participants of this study were somewhat taller and heavier than the CDC reference population, reflecting the higher prevalence of overweight and obesity, and taller stature, in contemporary populations (28,29). As a result, the LM-height-z and FM-height-z calculated for this study were lower than they would have been had body composition data been available to generate LM-height-z and FM-height-z from the CDC population. However, because we were interested in comparing the relationships between BMI-age-z and each of LM-height-z and FM-height-z among CKD participants with those among healthy participants, and not in the absolute differences between BMI-age-z and LM-height-z or FM-height-z, the different reference populations do not affect interpretation of study results. When analyses were repeated using both BMI-for-age centile curves and Z-scores generated using data from our healthy participants, the results were identical.

Discussion

Although children with CKD are short and sexually immature compared with healthy children of the same age, this study demonstrates that the heights and height-ages of children with CKD are similar to the heights and chronologic ages of (younger) healthy children at the same stage of sexual maturation. In other words, it appears that, in CKD, height-age reflects physical developmental age in a way similar to that of chronologic age in healthy children.

We have also shown that BMI expressed relative to chronologic age (BMI-age-z) underestimates both relative LM and adiposity in children and adolescents with CKD. Therefore, using BMI-age-z may result in overdiagnosis of underweight in this population. Underestimation of relative LM was greater in males than females, whereas underestimation of adiposity was more marked in females.

An understanding of the normal changes in body composition that occur with sexual development is important for the interpretation of these findings. Over the course of pubertal development, males experience a substantial increase in LM relative to height (30). In contrast, females experience important increases in adiposity during puberty and only modest increases in relative LM (31). BMI increases during sexual development in both sexes, but in males this reflects an increase in relative LM, whereas in females, increases in BMI are due primarily to increases in adiposity. When sexually immature females with CKD are compared with more developed healthy females of the same chronologic age, they appear to have inappropriately low adiposity, when in fact their adiposity may be appropriate for their level of maturation. Similarly, males with CKD and delayed maturation will appear to have LM deficits compared with healthy boys of the same age but of more advanced sexual development.

By expressing BMI relative to height-age rather than chronologic age, children with CKD are effectively compared with healthy children of a similar height and stage of development, resulting in more accurate estimates of relative LM and adiposity from BMI. We showed that the relations between BMI-height-age-z and each of relative LM (LM-height-z) and adiposity (FM-height-z) in CKD mirror the relations between BMI-age-z and each of relative LM and adiposity in healthy children and adolescents. Although BMI-age-z did not significantly underestimate relative LM and adiposity in all CKD stages, BMI-height-age-z performed as well or better in all CKD stages.

There are some caveats to using BMI-height-age-z in the assessment of individuals with CKD. Adolescents with CKD may have short stature even after completion of sexual maturation; height-age will underestimate maturation in this case and should therefore not be used to determine BMI z-score. Short stature in CKD may also be more marked than expected based solely on delayed maturation. When short stature is out of proportion with the degree of delay in sexual maturation, expressing BMI relative to height-age will lead to overestimation of adiposity and relative LM. A careful assessment of sexual maturation, and estimation of the physical developmental age, is important in the interpretation of BMI. In addition, we did not assess the appropriateness of using height-age to determine BMI z-score in children younger than 5 years of age; this area requires further study.

BMI and measures of body composition were expressed relative to height-age in prior studies of nutrition and body composition in children with CKD, in an effort to account for the abnormal relationships between age, height, and maturation in CKD (12,32). Although this study suggests that this is a useful and valid approach in clinical practice—and is preferable to expressing these measures relative to chronologic age—it is an imperfect solution for research. A preferable approach is to compare individuals with CKD with a healthy reference population and to use regression methods to adjust for differences in the joint distributions of age, height, and sexual maturation, as previously described in these same study participants (1).

It is also important to remember that no matter how BMI is expressed, it is not a measure of body composition but rather a measure of weight for height. In healthy populations, the relative proportions of fat and lean vary little among individuals of the same height, weight, sex, and age; therefore, BMI reasonably reflects body composition. However, in individuals with CKD, muscle deficits may be present, accompanied by excess adiposity or fluid overload (1). In such cases, weight for height may be preserved in the face of abnormal body composition. Body composition abnormalities may be subtle in children with CKD. In our previous study of the same children with CKD, we were unable to detect deficits in whole-body LM among participants with predialysis CKD, even though leg muscle deficits were evident in CKD stages 4 and 5 (1). The present study does not address differences in body composition between children with CKD and healthy children.

In conclusion, expressing BMI relative to chronologic age results in significant underestimation of relative LM and adiposity in children and adolescents with CKD and may result in overdiagnosis of underweight. Height-age appears to be a reasonable surrogate for physical developmental age in children with CKD. Therefore, BMI expressed relative to height-age reflects relative LM and adiposity in children with CKD in a way similar to that of BMI expressed relative to age in healthy children. However, given the inability of BMI to distinguish LM from FM, conclusions regarding the appropriateness of relative LM or adiposity based on BMI should be made with caution, especially in severe CKD. In the absence of clinically feasible alternatives, BMI-height-age-z represents a reasonable tool in the nutritional assessment of children with CKD that appears to be superior to BMI-age-z.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK060030, R01-HD040714, K24-DK076808, and F32-DK062637) and by the General Clinical Research Centers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. B.J.F. is a member of the McGill University Health Centre Research Institute (supported in part by the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec). During data analysis, B.J.F. was support by the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec and by a KRESCENT New Investigator award, jointly funded by the Kidney Foundation of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the Canadian Society of Nephrology.

This work was presented in abstract form at the 2009 American Society of Nephrology meeting, San Diego, California, October 29–31, 2009.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org

References

- 1.Foster BJ, Kalkwarf HJ, Shults J, Zemel BS, Wetzsteon RJ, Thayu M, Foerster DL, Leonard MB: Association of chronic kidney disease with muscle deficits in children. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 377–386, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster BJ, Leonard MB: Measuring nutritional status in children with chronic kidney disease. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 801–814, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schärer K, Study Group on Pubertal Development in Chronic Renal Failure : Growth and development of children with chronic renal failure. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 366: 90–92, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.KDOQI Work Group : KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Nutrition in Children with CKD: 2008 update. Executive summary. Am J Kidney Dis 53[Suppl 2]: S11–S104, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA: Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 73: 25–29, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khosla T, Lowe CR: Indices of obesity derived from body weight and height. Br J Prev Soc Med 21: 122–128, 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, Heo M: What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? Eur J Clin Nutr 59: 419–425, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman DS, Ogden CL, Berenson GS, Horlick M: Body mass index and body fatness in childhood. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 8: 618–623, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman DS, Sherry B: The validity of BMI as an indicator of body fatness and risk among children. Pediatrics 124[Suppl 1]: S23–S34, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman DS, Wang J, Maynard LM, Thornton JC, Mei Z, Pierson RN, Dietz WH, Horlick M: Relation of BMI to fat and fat-free mass among children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond) 29: 1–8, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL: CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data 314: 1–27, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaefer F, Wühl E, Feneberg R, Mehls O, Schärer K: Assessment of body composition in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol 14: 673–678, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz GJ, Feld LG, Langford DJ: A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in full-term infants during the first year of life. J Pediatr 104: 849–854, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz GJ, Muñoz A, Schneider MF, Mak RH, Kaskel F, Warady BA, Furth SL: New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 629–637, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Kidney Foundation: Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S128–S142, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, Grummer-Strawn LM, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics 109: 45–60, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duke PM, Litt IF, Gross RT: Adolescents’ self-assessment of sexual maturation. Pediatrics 66: 918–920, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner JM: Growth at Adolescence, Oxford, Blackwell Scientific Publication, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis KJ, Shypailo RJ, Abrams SA, Wong WW: The reference child and adolescent models of body composition. A contemporary comparison. Ann N Y Acad Sci 904: 374–382, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis KJ: Body composition of a young, multiethnic, male population. Am J Clin Nutr 66: 1323–1331, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goulding A, Taylor RW, Gold E, Lewis-Barned NJ: Regional body fat distribution in relation to pubertal stage: A dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry study of New Zealand girls and young women. Am J Clin Nutr 64: 546–551, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lloyd T, Chinchilli VM, Eggli DF, Rollings N, Kulin HE: Body composition development of adolescent white females: The Penn State Young Women’s Health Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 152: 998–1002, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogle GD, Allen JR, Humphries IR, Lu PW, Briody JN, Morley K, Howman-Giles R, Cowell CT: Body-composition assessment by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry in subjects aged 4-26 y. Am J Clin Nutr 61: 746–753, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuerst T, Genant HK: Evaluation of body composition and total bone mass with the Hologic QDR 4500 [Abstract PMo474]. Osteoporos Int 6: 202, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole TJ: The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr 44: 45–60, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thayu M, Denson LA, Shults J, Zemel BS, Burnham JM, Baldassano RN, Howard KM, Ryan A, Leonard MB: Determinants of changes in linear growth and body composition in incident pediatric Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 139: 430–438, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thayu M, Shults J, Burnham JM, Zemel BS, Baldassano RN, Leonard MB: Gender differences in body composition deficits at diagnosis in children and adolescents with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 13: 1121–1128, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM: Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA 291: 2847–2850, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster BJ, Shults J, Zemel BS, Leonard MB: Interactions between growth and body composition in children treated with high-dose chronic glucocorticoids. Am J Clin Nutr 80: 1334–1341, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loomba-Albrecht LA, Styne DM: Effect of puberty on body composition. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 16: 10–15, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siervogel RM, Demerath EW, Schubert C, Remsberg KE, Chumlea WC, Sun S, Czerwinski SA, Towne B: Puberty and body composition. Horm Res 60[Suppl 1]: 36–45, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rashid R, Neill E, Smith W, King D, Beattie TJ, Murphy A, Ramage IJ, Maxwell H, Ahmed SF: Body composition and nutritional intake in children with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol 21: 1730–1738, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]