Abstract

Chemically induced skin carcinomas in mice are a paradigm for epithelial neoplasia, where oncogenic ras mutations precede p53 and INK4a/ARF mutations during the progression toward malignancy. To explore the biological basis for these genetic interactions, we studied cellular responses to oncogenic ras in primary murine keratinocytes. In wild-type keratinocytes, ras induced a cell-cycle arrest that displayed some features of terminal differentiation and was accompanied by increased expression of the p19ARF, p16INK4a, and p53 tumor suppressors. In ARF-null keratinocytes, ras was unable to promote cell-cycle arrest, induce differentiation markers, or properly activate p53. Although oncogenic ras produced a substantial increase in both nucleolar and nucleoplasmic p19ARF, Mdm2 did not relocalize to the nucleolus or to nuclear bodies but remained distributed throughout the nucleoplasm. This result suggests that p19ARF can activate p53 without overtly affecting Mdm2 subcellular localization. Nevertheless, like p53-null keratinocytes, ARF-null keratinocytes were transformed by oncogenic ras and rapidly formed carcinomas in vivo. Thus, oncogenic ras can activate the ARF-p53 program to suppress epithelial cell transformation. Disruption of this program may be important during skin carcinogenesis and the development of other carcinomas.

Normal cells possess natural defense mechanisms that counter uncontrolled mitogenic signaling, and these safeguards may be eliminated by mutation during multistage carcinogenesis (1). One such safeguard is illustrated by the transforming interactions between oncogenic ras and various tumor suppressor genes in primary fibroblasts. The ras family of proto-oncogenes are small GTPases that, when activated by mutation, constitutively transmit growth promoting signals via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade and other pathways (2). Oncogenic ras readily transforms immortal rodent cell lines; however, it is unable to transform primary cells because it induces a premature senescence program involving tumor suppressors such as p53, p16INK4a, p19ARF, p15INK4b, and the promyelocytic leukemia gene product (PML; refs. 3–7). Importantly, mutations that disable the arrest program cooperate with ras in transformation (5, 8–10). Given the high frequency of ras, p53, and INK4a/ARF mutations in human cancers (11), this safeguard may be an important tumor suppressor mechanism.

The INK4a/ARF locus is a critical sensor of hyperproliferative signals produced by ras and other oncogenes (12). This locus encodes the two structurally unrelated tumor suppressors p16INK4a and p19ARF (13, 14). p16 INK4a, an inhibitor to cyclin D-dependent kinase, regulates the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein to block the G1-S transition (15). In contrast, p19ARF can activate p53 by interfering with the p53 antagonist Mdm2 (16–19), leading to cell-cycle arrest or apoptosis depending on context (12). Both p16INK4a and p19ARF accumulate during the serial passaging of cells in culture (20–22), and can be induced acutely by expression of mitogenic oncogenes (4, 21–23). Oncogenic ras induces p16INK4a and p19ARF through the MAPK cascade, suggesting that the process is directly coupled to the pro-mitogenic activity of oncogenic ras (9). Both p16INK4a and p19ARF may contribute to premature senescence in human cells, whereas p19ARF dominates the program in rodent cells (4, 9, 22). Thus, primary fibroblasts derived from ARF−/− mice fail to arrest in response to oncogenic ras and are transformed by ras alone (4, 24).

Fail-safe mechanisms involving ras, the INK4a/ARF locus, and p53 have been described in fibroblasts, but much less is known about the processes in epithelial cells—the normal precursor to most adult cancers. Perhaps the most well characterized model of epithelial neoplasia involves chemically induced skin carcinogenesis in mice (25). In this paradigm, animals are treated with a carcinogen, 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA), and a tumor promoter, phorbol 12-tetradecanoate 13-acetate (TPA). DMBA treatment produces ras mutations and, with continued application of TPA, benign papillomas. Progression to squamous cell carcinomas is a rare event that requires additional mutations, including inactivation of p53 and the INK4a/ARF locus (25). Although the biological basis for these genetic interactions is unknown, they can be recapitulated by using transgenic and knockout mice. For example, loss of p53 promotes the progression, but not initiation, of chemically induced carcinomas (26).

The epidermal keratinocyte is the normal cell precursor to squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. In normal skin, keratinocytes undergo a continuous process of proliferation and differentiation as a self-renewal program (27). This differentiation program is characterized by an irreversible cell-cycle exit and the induction of well-established differentiation markers (27). Primary murine keratinocytes proliferate for several passages in culture, but undergo a normal differentiation program after calcium addition (28). Notably, oncogenic ras cooperates with p53 loss to oncogenically transform primary keratinocytes (29), demonstrating that this simplified system recapitulates the genetic interactions involved in tumor progression in vivo. In this study, we examined cellular responses to ectopic expression of oncogenic ras in primary epidermal keratinocytes. Our results highlight the role of ARF-p53 pathway during epithelial cell transformation, and suggest a biological basis for genetic interactions involved in chemically induced skin carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

Primary epidermal keratinocytes populations were prepared from newborn mice (2 days old) that are wild-type, ARF-null (24), and p53-null (30) by using a previously published protocol (31) with minor modifications. Briefly, mice skins were floated, dermis down, in 0.05% trypsin/0.5 mM EDTA at 4°C overnight. Afterward, skin pieces were placed with the dermis-side up, and the dermis was peeled back with a forceps. Keratinocytes were isolated by trypsinizing the tissues for an additional 15 min at 37°C. Cells were collected, washed in PBS containing 0.5% FBS and were resuspended in serum-free keratinocyte medium with supplements [recombinant epidermal growth factor/bovine pituitary extract (GIBCO)/50 units/ml penicillin G/25 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate/0.3 mM Ca2+]. Cells were plated at 0.5 mouse equivalents per 60-mm Petri dish, after which the medium was changed and the calcium concentration was reduced to 0.05 mM. Keratinocytes were subcultured once (1:3 dilution) for subsequent experiments.

Retroviral Gene Transfer.

Helpervirus-free retroviruses expressing H-rasV12 [pBabe-Puro-ras (3)] or an empty vector were produced by transient transfection of the Phoenix ecotropic packaging line (G. Nolan, Stanford University) as previously described (3). Filtered supernatant supplemented with 4 μg/ml polybrene was used to infect freshly isolated mouse skin keratinocytes within 24 to 48 hr postplating (3). Meanwhile, the packaging cells were replenished with keratinocyte medium containing 10% Chelex-treated FBS (Chelex-100, Sigma), and the virus-containing supernatant was collected every 6 hr for two additional infections. Twelve hours after the last infection, the cells were selected in 1.5 μg/ml puromycin for 48 h.

Measurement of Cell Proliferation.

Mouse skin keratinocytes were plated onto LAB-TEK Chamber Slides (Nalge Nunc) and were subsequently labeled with BrdU (100 μg/ml, Sigma) and 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FdU, 10 μg/ml, Sigma) for 12 h. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 15 min. After fixation, cells were permeabilized, denatured, and labeled with BrdU as previously described (9). BrdU incorporation was measured by immunofluorescence by using an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (1:200, Amersham Pharmacia), and DNA was stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml). DNA content analysis by using propidium iodide and flow cytometry was carried out as described (9).

Immunoblotting.

Western blot analysis was carried out on whole cell lysates as previously described by using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham) detection (9). Typically, 20 μg of proteins from each sample were loaded and separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore). Blots were probed with the following antibodies: anti-p53 (CM5, 1:2000, Novocastra, Newcastle, U.K.), anti-p19ARF (1:500, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), anti-p16 (M156, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-p21 (C-19, 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-mouse keratin 5 (K5, 1:1000, BAbCO, Richmond, CA), anti-Ras (OP23, 1:200, Oncogene), anti-involucrin (1:1000, BAbCO), anti-filaggrin (1:2000, BAbCO).

Immunostaining.

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by permeabilization in 0.2% Triton X-100/0.5% normal goat serum/PBS. Cells were subsequently incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with the following antibodies, respectively: CM5 (anti-p53, Novocastra, 1:200), anti-p19ARF (Novus Biologicals, 1:100), anti-Mdm2 (2A10 or 4B11, generously provided by Dr. A. Levine, The Rockefeller University, 1:50), anti-K5 (1:1000, BAbCO), anti-involucrin (1:600, BAbCO), and anti-fibrillarin (1:50, Sigma). Alexa Fluor Conjugates (Molecular Probes) were used as the secondary antibodies, and DNA was visualized by using DAPI. Confocal images were obtained by using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser scanning microscope.

Tumorigenicity Assays.

Two days after selection, retrovirally transduced cells were collected, and 5 × 105 cells were injected s.c. into nude mice (two sites/mouse). Tumor growth was monitored every 3 days by palpation at the sites of injection. The length (L) and width (W) were measured by using a caliper, and the volume of tumor formed was determined by using the formula V = (L × W2/2. After 3 weeks, each tumor was dissected, weighed, and fixed in formalin for staining with hematoxylin and eosin.

Results

Oncogenic ras Induces Cell Cycle Arrest in Primary Murine Keratinocytes.

Primary epidermal keratinocytes were isolated from newborn mice and cultured in serum-free medium by using conditions that do not support fibroblast growth. By using this procedure, pure keratinocyte populations were obtained, as judged by their polygonal morphology and immunoreactivity with a K5-specific antibody (Fig. 1). Twenty-four hours later, keratinocytes were infected with high-titer retroviruses coexpressing oncogenic ras (H-rasV12) with a puromycin resistance gene to isolate cells in which the virus was stably transduced. A vector expressing the puromycin resistance gene alone was used as a control. This procedure resulted in the infection of >30% of keratinocytes as measured in parallel infections by using a green fluorescence protein (GFP)-encoding retrovirus (data not shown). Infected cell populations were selected for 2 days in puromycin, and then subcultured once for all subsequent analyses. Hence, this procedure allowed us to examine the biological consequences of ras expression in whole primary cell populations without substantial growth or selection in culture.

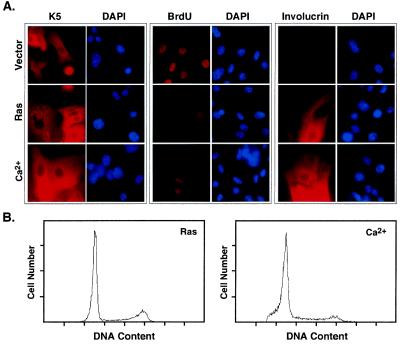

Figure 1.

Oncogenic ras arrests primary murine keratinocytes. Primary epidermal keratinocytes were infected with a control (Vector) or H-rasV12 (Ras) retroviral vector. Alternatively, the cells were treated with medium containing 1.4 mM Ca2+ (Ca2+) to induce terminal differentiation. (A) Keratinocyte populations were analyzed for K5 and involucrin expression by indirect immunofluorescence using antibodies directed against each protein. Cell proliferation was measured by incubating cells with BrdU for 12 h, and identifying BrdU-positive cells by immunofluorescence by using an antibody against BrdU. Cells were counterstained with DAPI. Representative fields are shown. (B) Cell cycle distribution of keratinocytes 48 hr after selection or calcium treatment. Cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide for the DNA content analysis by using flow cytometry.

Oncogenic ras expression produced marked changes to keratinocyte morphology and proliferation that were not apparent in populations expressing the control vector (Fig. 1A; see also Figs. 2 and 3). By using a BrdU incorporation assay to determine the percentage of cells synthesizing DNA, we observed a substantial reduction in proliferation within 3 days of oncogenic ras transduction (Fig. 1A, quantified in 2B). The reduction of BrdU incorporation was similar to that produced by the addition of exogenous calcium (Figs. 1A and 2B left), a stimulus that initiates a normal program of terminal differentiation (28). Cells arrested by both oncogenic ras and exogenous calcium displayed a predominantly 2N DNA content, although ras-expressing cells retained more cells with a 4N content (Fig. 1B). The DNA content profile of ras-expressing cells was similar to vector-expressing controls (data not shown), with the only major difference being a lack of BrdU incorporation in the ras-arrested cells (Fig. 1A). Similarly, cells arrested by both oncogenic ras and exogenous calcium displayed features of terminal differentiation (Fig. 1A; see also Fig. 3). For example, immunofluorescence experiments revealed that ≈30% of the ras-expressing keratinocytes were positive for involucrin (Fig. 1A), a major protein precursor of the epidermal cornified envelope and a differentiation marker (32). However, calcium-induced differentiation was more robust, because virtually 100% of these cells were involucrin-positive. Therefore, oncogenic ras can induce a cell-cycle arrest in epidermal keratinocytes that has some features of terminal differentiation.

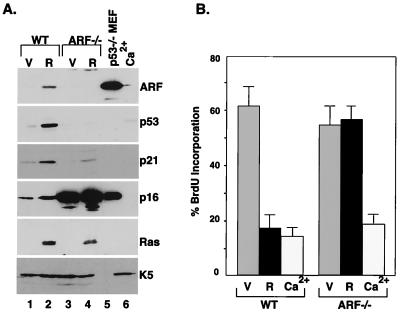

Figure 2.

p19ARF is required for ras-induced arrest of keratinocytes. Primary skin keratinocytes were isolated from wild-type (WT) or ARF-null (ARF−/−) mice. Cell populations were transduced with a control vector (V) or oncogenic ras (R), or were with 1.4 mM Ca2+ for 48 h. (A) Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates by using antibodies against p19ARF, p53, p21, p16INK4a, Ras, and K5. p53-null (p53−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were used as a control. (B) The cell populations described above were labeled with BrdU and fixed, and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells was determined by immunofluorescence by using an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells was determined by counting the BrdU-positive cells among at least 200 cells from each sample. The results represent the mean ± SD from three experiments.

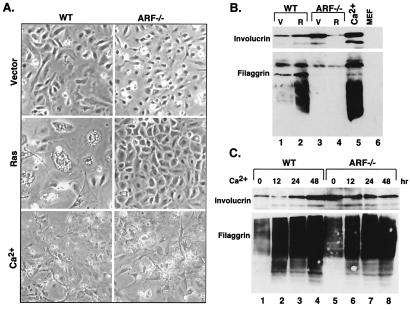

Figure 3.

p19ARF is not required for terminal differentiation. (A) Morphological appearance of the cell populations described in Fig. 2. Photographs were taken 48 hr after selection for virus-infected cells, or 48 hr after calcium treatment. (B) Expression of differentiation-associated markers, as shown by using immunoblotting with antibodies directed against involucrin and filaggrin. Extracts from MEFs were used for comparison. V, vector; R, H-rasV12. (C) Expression of differentiation-associated markers in wild-type (WT) and ARF−/− keratinocytes treated with exogenous calcium. Cell extracts were prepared at the indicated times posttreatment, and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies directed against involucrin or filaggrin.

p19ARF Is Required for ras-Induced Arrest.

In fibroblasts, ras-induced cell-cycle arrest is accompanied by up-regulation of several tumor suppressors, including p53, p16INK4a, p19ARF, p15INK4b, and promyelocytic leukemia gene product (PML), and each of these proteins contributes to the arrest program in some settings (3–7). To determine whether some of these proteins are altered during ras-induced arrest in keratinocytes, we performed a series of Western blots on total cell extracts from ras-expressing keratinocytes and their normal (vector) counterparts. Expression of oncogenic ras produced substantial increases in p19ARF, p53, the p53 transcriptional target p21, and p16 within 4 days of gene transfer (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 and 2). A similar increase in p19ARF and p53 occurred in keratinocytes expressing a constitutively activated MAPK kinase (MEK1Q56P), implying that Ras induced p19ARF and p53 through deregulated MAPK signaling (data not shown). Remarkably, p16INK4a expression was extremely high in ARF-null keratinocytes (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 1 and 3), suggesting that ARF-null cells are resistant to p16 inhibition, or that the expressed p16 is not an effective cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor.

In murine fibroblasts, ARF and p53 are required for ras-induced arrest, because disruption of either gene circumvents arrest and allows uncontrolled proliferation (3, 4). To determine whether the ARF-p53 pathway is operative in keratinocytes, we tested whether oncogenic ras could induce p53 and promote cell-cycle arrest in keratinocytes derived from ARF-null (ARF−/−) mice. Oncogenic ras did not induce p53 in ARF−/− keratinocytes, and the induction of p21 was substantially reduced compared with wild-type cells (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 2 and 4). Furthermore, ARF−/− cells did not arrest in response to oncogenic ras, and incorporated as much BrdU as controls (Fig. 2B). It seems unlikely that the failure of ARF−/− cells to arrest is due to rare secondary mutations that exist in these cells, because a large percentage of the initial populations were infected and then analyzed within days. Similar results were observed in p53−/− keratinocytes (data not shown). Thus, disruption of ARF prevents ras-induced arrest in murine keratinocytes, apparently because ras is unable to efficiently activate p53.

Consistent with their failure to arrest, ARF−/− cells expressing oncogenic ras did not acquire features of terminal differentiation. Hence, these cells did not acquire the enlarged and flat morphology characteristic of ras-arrested controls (Fig. 3A). Similarly, as shown by immunoblotting of SDS/polyacrylamide gels, these cells did not induce involucrin or filaggrin, another differentiation-associated marker (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 2 and 4). During keratinocyte differentiation, involucrin and filaggrin are processed and expressed in multiple electrophoretically distinct forms (33, 34). Although these expression patterns were induced by ras in normal keratinocytes, they were not detected in ARF−/− cells. Paradoxically, ARF−/− cells reproducibly displayed substantially higher levels of involucrin than wild-type cells, although the significance of this observations is unknown (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 1 and 3). Together, these data indicate that the induction of differentiation-associated markers by oncogenic ras is not a direct consequence of Ras signaling but, rather, accompanies cell-cycle arrest.

p19ARF Is Not Required for Terminal Differentiation Induced by Calcium.

Although p19ARF was required for the induction of differentiation markers by oncogenic ras, it was dispensable for terminal differentiation initiated by exogenous calcium. Thus, calcium did not induce p19ARF or other tumor suppressors in primary keratinocytes (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 2 and 6), and ARF−/− keratinocytes underwent an apparently normal differentiation program (Fig. 2B). Specifically, ARF−/− keratinocytes were morphologically indistinguishable from controls after calcium treatment (Fig. 3A), and achieved a similar increase in involucrin and filaggrin as occurred in wild-type cells (Fig. 3C). In fact, ARF−/− cells treated with calcium appeared more fully differentiated than normal cells expressing oncogenic ras; for example, ARF−/− cells treated with calcium became stratified and formed tight junctions, whereas normal cells expressing oncogenic ras did not (Fig. 3A; data not shown). Clearly, the requirement for p19ARF during ras-induced arrest distinguishes this process from normal differentiation.

p19ARF Does Not Overtly Alter Mdm2 Localization in ras-Arrested Keratinocytes.

Studies suggest that p19ARF activates p53 by interfering with the ability of Mdm2 to antagonize p53 (35). In some settings, p19ARF sequesters Mdm2 in the nucleolus, allowing p53 to function unopposed in the nucleoplasm (36, 37). To determine whether p19ARF alters Mdm2 localization in keratinocytes, we examined the distribution of p19ARF, p53, and Mdm2 in control and ras-arrested keratinocytes by using antibodies specific for each protein. Consistent with the immunoblotting experiments, p19ARF and p53 were elevated in keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras compared with controls (Fig. 4 A and B). As expected, a substantial amount of p19ARF localized to the nucleolus, as demonstrated by its colocalization with the nucleolar marker, fibrillarin (Fig. 4 A and D). However, p19ARF also was expressed in the nucleoplasm. Thus, the anti-p19ARF antibody produced clear nuclear staining that did not only colocalize with fibrillarin (Fig. 4A) and was not present in ARF−/− counterparts (data not shown). Conversely, whereas p53 was expressed in the nucleoplasm, a substantial amount colocalized with fibrillarin in the nucleolus (Fig. 4B). The immunofluorescence signal was specific for p53, because p53−/− cells expressing oncogenic ras did not show nucleolar staining (data not shown). Whether nucleolar p53 is functionally active remains to be determined.

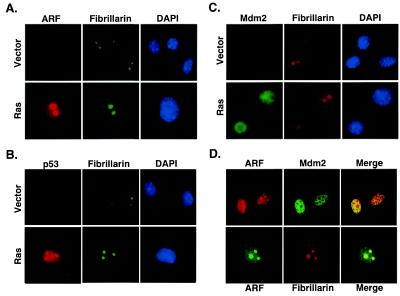

Figure 4.

p19ARF colocalizes with Mdm2 in the nucleoplasm of ras-arrested keratinocytes. The subcellular localization of p19ARF (A), p53 (B), and Mdm2 (C) was determined in keratinocyte populations expressing a vector control (Vector) or oncogenic ras (Ras) by immunofluorescence using antibodies specific for each protein (see Materials and Methods). Each cell population was costained with fibrillarin to mark the nucleolus, and counterstained with DAPI to identify the nucleus. (D) ras-arrested keratinocytes were fixed, costained with antibodies directed against p19ARF and Mdm2, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Note that the antibodies for p19ARF and p53 did not show a signal in ARF−/− and p53−/− cells (data not shown). All images were representative of multiple fields and experiments.

Although Mdm2 also accumulated in keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras, it did not localize to the nucleolus (Fig. 4C). In fact, as indicated by using both standard immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy, Mdm2 was distributed throughout the nucleoplasm and excluded from the nucleolus (Fig. 4 C and D). This nucleoplasmic staining was diffuse and did not localize to nuclear bodies as has been described in some settings (17). Although the experiments shown in Fig. 4 used the monoclonal antibody 2A10 to detect Mdm2, we obtained identical results by using antibody 4B11, which recognizes a distinct Mdm2 epitope (data not shown). These results suggest that, at least in keratinocytes, p19ARF does not activate p53 by sequestering Mdm2 in the nucleolus. Indeed, the only compartment where p19ARF and Mdm2 were coexpressed was in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 4D).

ARF-Null Keratinocytes Expressing Oncogenic ras Form Squamous Cell Carcinomas.

In murine fibroblasts and lymphoid cells, p19ARF appears to activate p53 as part of a protective mechanism that limits the transforming potential of mitogenic oncogenes (35). In keratinocytes, p53 loss can facilitate ras-induced transformation, because p53−/− cells expressing oncogenic ras are highly tumorigenic in immunocompromised mice (29). To determine whether inactivation of ARF would also facilitate keratinocyte transformation, we introduced oncogenic ras into wild-type, ARF+/−, and ARF−/− cells and tested the ability of infected populations to form tumors when injected s.c. into athymic “nude” mice. For comparison, we also tested p53−/− cells expressing oncogenic ras, as well as all cell populations infected with the control retroviral vector. Infected cell populations were selected with puromycin for 48 h, grown for 2 days in culture, and injected s.c. into nude mice. Tumor growth was measured with time; at 3 weeks, tumors were removed, weighed, and prepared for histological analysis.

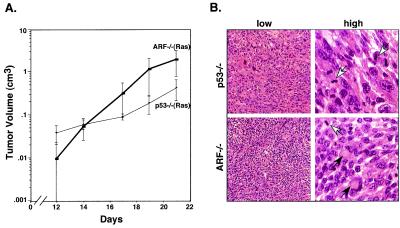

Wild-type keratinocytes were not tumorigenic, irrespective of whether they were controls or expressed oncogenic ras (Table 1). In contrast, ARF−/− keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras gave rise to rapidly growing tumors within 2 weeks of injection (Fig. 5; Table 1). p53−/− keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras also formed tumors, with a kinetics and frequency similar to ARF−/− cells (Fig. 5A; Table 1). Neither ARF−/− nor p53−/− keratinocytes harboring the control vector formed tumors (Table 1). Interestingly, ARF+/− keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras also formed tumors (Table 1) and, as determined by using an allele-specific PCR assay on tumor-derived DNA, those tumors that formed lost the remaining wild-type ARF allele (data not shown). These results imply that ARF is strongly selected against during tumor outgrowth. In all cases, the tumors had features of undifferentiated squamous cell carcinomas, and were anaplastic with aberrant mitotic figures (Fig. 5B, Table 1). Taken together, these data demonstrate that p19ARF suppresses ras-induced transformation in epidermal keratinocytes, presumably by coupling Ras mitogenic signaling to a p53 arrest program. As a result, loss of ARF can cooperate with ras to promote squamous cell carcinomas.

Table 1.

Tumorigenicity assay

| Genotype* | Tumorigenicity† | Tumor weight, g‡ | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT (Vector) | 0/6 | NA | NA |

| WT (Ras) | 0/6 | NA | NA |

| p53−/− (Vector) | 0/2 | NA | NA |

| p53−/− (Ras) | 4/4 | 0.27 ± 0.15 | SCC§ |

| ARF−/− (Vector) | 0/5 | NA | NA |

| ARF−/− (Ras) | 5/5 | 0.9 ± 0.5 | SCC§ |

| ARF+/− (Ras) | 3/3¶ | 0.86 ± 1.27 | SCC¶ |

Primary skin keratinocytes were derived from wild-type (WT), ARF-null (ARF−/−), ARF heterozygous (ARF+/−), and p53-null (p53−/−) mice and were infected with control vector (Vector) or H-rasV12 (Ras).

Tumorigenicity is defined as the ratio between the number of tumors arising to the number of sites injected. Mice harboring tumors were examined for 3 weeks; mice that did not form tumors were examined for up to 3 months.

Tumor weights were measured 3 weeks after injection of cells.

SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Allele-specific PCR revealed loss of the remaining wild-type ARF allele in all tumors.

Figure 5.

ARF-null keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras form carcinomas in vivo. Primary keratinocyte cultures derived from wild-type, ARF−/−, and p53−/− mice were infected with ras-expressing retroviruses or a control vector, and 5 × 105 cells (per site) were injected s.c. into the rear flanks of athymic nude mice. (A) Tumor growth was monitored by biweekly caliper measurements of tumor masses at the site of injection. (B) Histological analysis of tumors derived from ARF−/− or p53−/− keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras. After 3 weeks, tumors were excised from mice and processed for staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Shown are representative examples at both low and high magnification. Both tumor types were classified as aggressive and relatively undifferentiated squamous cell carcinomas. All tumors were anaplastic, with poor cellular organization and without fibrous stroma within the masses. Most tumors also had multiple areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. White arrows, mitotic figures; black arrows, keratin pearls.

Discussion

In this study, we examined cellular responses to oncogenic ras in primary epidermal keratinocytes—a well-characterized epithelial cell type that can be readily isolated from mice and is the precursor for chemically induced skin carcinomas. As previously reported for fibroblasts, expression of oncogenic ras in keratinocytes induces p19ARF, p16INK4a, and p53, leading to a cell-cycle arrest program. Similarly, an activated MEK1—a downstream effector or Ras in the MAPK cascade—recapitulates the effects of oncogenic ras in promoting both fibroblast and keratinocyte arrest [(9); data not shown]. However, whereas the arrest program of fibroblasts resembles cellular senescence, the process in keratinocytes is reminiscent of terminal differentiation. In keratinocytes, loss of p19ARF uncouples Ras signaling from p53 leading, ultimately, to oncogenic transformation. Thus, both ARF−/− and p53−/− keratinocytes expressing oncogenic ras rapidly form carcinomas on injection into nude mice. Previous reports introducing v-H-ras (instead of the H-rasV12 used here) into keratinocytes did not observe an obvious arrest, although v-H-ras does transform p53−/− and p21−/− keratinocytes (29, 38, 39). Although in this study we cannot rule out the possibility that p19ARF also acts independently of p53 (40), our results provide the first direct evidence that the ARF-p53 pathway can suppress epithelial cell transformation.

That ras-arrested keratinocytes display features of terminally differentiated skin raises the possibility that ras might transmit differentiation signals during normal skin differentiation. Consistent with this notion, Ras mediates a neuronal differentiation program in PC12 cells after nerve growth factor (NGF) addition (41), and MAPK activity is induced in keratinocytes after addition of exogenous calcium (42). However, ras-induced arrest in keratinocytes is distinct from terminal differentiation. First, although ras-expressing keratinocytes induce certain differentiation markers, the effect is not as robust as observed after calcium addition, nor do the arrested cells acquire the morphology of terminally differentiated keratinocytes. More importantly, the cell-cycle regulators that are activated in response to oncogenic ras are not induced during terminal differentiation (e.g., p19ARF, p53, p21, and p16INK4a), and mice lacking these genes develop normal skin (8, 9, 24, 39, 43, 44). In fact, we show that ARF−/− keratinocytes are capable of terminal differentiation although they fail to arrest in response to oncogenic ras. Therefore, ras-induced arrest and differentiation achieve overlapping endpoints by using fundamentally different mechanisms. This observation may reflect the unique purpose of each program: whereas terminal differentiation of keratinocytes produces cellular specialization, ras-induced arrest of keratinocytes—like premature senescence in fibroblasts—counters uncontrolled mitogenic signaling.

How does p19ARF activate p53 in ras-expressing keratinocytes? In normal cells, p53 protein level is tightly controlled by Mdm2. Mdm2 antagonizes p53 function by preventing p53-dependent transcription, by acting as an E3 ligase to facilitate p53 degradation, and by promoting p53 nuclear export (35). p19ARF physically associates with Mdm2, which presumably uncouples Mdm2 from p53 (16–19). How this uncoupling occurs may depend on context, but most studies suggest that p19ARF alters Mdm2 compartmentalization. For example, some studies demonstrate that p19ARF sequesters Mdm2 in the nucleolus (37, 45), whereas another observes colocalization of p19ARF and Mdm2 in nuclear bodies (17). In either setting, p53 is liberated to act unopposed in the nucleoplasm. p19ARF also interferes with the nuclear export functions of Mdm2, leading to Mdm2 accumulation in the nucleolus and, in principle, active p53 in the nucleoplasm (36). In keratinocytes, oncogenic ras produces a substantial increase in nucleolar and nucleoplasmic p19ARF, but Mdm2 does not relocalize to the nucleolus or to nuclear bodies. Instead, Mdm2 colocalizes with the fraction of p19ARF that distributes throughout the nucleoplasm. Of note, short N-terminal p19ARF peptides inhibit the Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination of p53 in solution (46, 47), and perhaps this anti-ubiquitination activity of p19ARF couples Ras signaling to p53 in keratinocytes. Thus, it appears that p19ARF can activate p53 through multiple mechanisms.

The responses of primary keratinocytes to oncogenic ras display remarkable parallels to the progression of chemically induced skin carcinomas in mice. We show that oncogenic ras is unable to transform primary keratinocytes, in part, because it activates a cell-cycle arrest program. Similarly, DMBA/ TPA treatment of murine skin—which produces endogenous ras mutations—produces benign papillomas that rarely progress (48). Interestingly, like ras-arrested keratinocytes, these papillomas have elevated levels of wild-type p53 (49). We show that oncogenic ras induces p19ARF and p53, and that loss of either protein prevents arrest and facilitates transformation. Similarly, the progression of chemically induced papillomas to squamous cell carcinomas is associated with mutations in p53 or at the INK4a/ARF locus (8, 26, 50). In addition, p53−/− mice display a remarkably high rate of malignant conversion of papillomas to carcinomas, whereas INK4a/ARF−/− and ARF−/− mice are prone to skin carcinomas induced by DMBA and UV irradiation (8, 50). Nevertheless, whereas ras-induced arrest in vitro occurs over several days, the DMBA-initiated cells harboring endogenous ras mutations undergo many population doublings before producing a benign papilloma. Perhaps the MAPK levels produced by ectopic ras expression exceed those produced by endogenous ras mutations, which may lead to a more accelerated arrest in vitro. Alternatively, growth factors in the microenvironment or TPA itself might delay or attenuate the arrest program. Such additional levels of regulation are not unprecedented; for example, Rho can suppress ras-mediated induction of p21, and microenvironmental survival factors govern the decision of myc-overexpressing cells to proliferate or undergo apoptosis (51, 52). In any case, our data provide a provocative explanation for genetic interactions that promote chemically induced skin carcinomas. Similar biological and genetic interactions may occur during the evolution of human carcinomas.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Sherr for ARF-null mice; G. Hannon, C. Sherr, and members of the Lowe Laboratory for helpful discussions and advice; G. Ferbeyre, E. de Stanchina, M. Narita, and E. Querido for critical readings of the manuscript; C. Rosenthal for animal husbandry; T. Howard for help with confocal microscopy; K. Velinzon for assistance with flow cytometry; K. Sokol for histology; and B. Stillman for support. We also thank the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Animal Facility and Graphic Arts Department for their patience and help. S.W.L. is a Rita Allen Scholar. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (AG16379).

Abbreviations

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- DMBA

7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene

- TPA

phorbol 12-tetradecanoate 13-acetate

- BrdU

5-bromodeoxyuridine

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- K5

keratin 5

References

- 1.Weinberg R A. Cell. 1997;88:573–575. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81897-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz M E, McCormick F. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano M, Lin A W, McCurrach M E, Beach D, Lowe S W. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmero I, Pantoja C, Serrano M. Nature (London) 1998;395:125–126. doi: 10.1038/25870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malumbres M, Perez De Castro I, Hernandez M I, Jimenez M, Corral T, Pellicer A. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2915–2925. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.8.2915-2925.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferbeyre G, de Stanchina E, Querido E, Baptiste N, Prives C, Lowe S W. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2015–2027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearson M, Carbone R, Sebastiani C, Cioce M, Fagioli M, Saito S, Higashimoto Y, Appella E, Minucci S, Pandolfi P P, Pelicci P G. Nature (London) 2000;406:207–210. doi: 10.1038/35018127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrano M, Lee H, Chin L, Cordon-Cardo C, Beach D, DePinho R A. Cell. 1996;85:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin A W, Barradas M, Stone J C, van Aelst L, Serrano M, Lowe S W. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3008–3019. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn W C, Counter C M, Lundberg A S, Beijersbergen R L, Brooks M W, Weinberg R A. Nature (London) 1999;400:464–468. doi: 10.1038/22780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan D, Weinberg R A. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherr C J. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2984–2991. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serrano M, Hannon G J, Beach D. Nature (London) 1993;366:704–707. doi: 10.1038/366704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quelle D E, Zindy F, Ashmun R A, Sherr C J. Cell. 1995;83:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherr C J. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3689–3695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois N J, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, Potes J, Chen K, Orlow I, Lee H W, Cordon-Cardo C, DePinho R A. Cell. 1998;92:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough W G. Cell. 1998;92:725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamijo T, Weber J D, Zambetti G, Zindy F, Roussel M F, Sherr C J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8292–8297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stott F J, Bates S, James M C, McConnell B B, Starborg M, Brookes S, Palmero I, Ryan K, Hara E, Vousden K H, Peters G. EMBO J. 1998;17:5001–5014. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reznikoff C A, Yeager T R, Belair C D, Savelieva E, Puthenveettil J A, Stadler W M. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2886–2890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zindy F, Eischen C M, Randle D H, Kamijo T, Cleveland J L, Sherr C J, Roussel M F. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2424–2433. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimri G P, Itahana K, Acosta M, Campisi J. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:273–285. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.1.273-285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Stanchina E, McCurrach M E, Zindy F, Shieh S Y, Ferbeyre G, Samuelson A V, Prives C, Roussel M F, Sherr C J, Lowe S W. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2434–2442. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel M F, Quelle D E, Downing J R, Ashmun R A, Grosveld G, Sherr C J. Cell. 1997;91:649–569. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balmain A, Harris C C. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:371–377. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemp C J, Donehower L A, Bradley A, Balmain A. Cell. 1993;74:813–822. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuspa S H, Hennings H, Tucker R W, Jaken S, Kilkenny A E, Roop D R. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;548:191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb18806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennings H, Michael D, Cheng C, Steinert P, Holbrook K, Yuspa S H. Cell. 1980;19:245–254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinberg W C, Azzoli C G, Kadiwar N, Yuspa S H. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5584–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams B O, Schmitt E M, Halachmi S, Bronson R T, Weinberg R A. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hennings H. In: Keratinocyte Methods. Leigh I, Watt F, editors. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1994. pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watt F M, Green H. Nature (London) 1982;295:434–436. doi: 10.1038/295434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dale B A, Scofield J A, Hennings H, Stanley J R, Yuspa S H. J Invest Dermatol. 1983;81:90s–95s. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12540769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michel S, Schmidt R, Robinson S M, Shroot B, Reichert U. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:301–305. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12466177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherr C J, Weber J D. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:94–99. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tao W, Levine A J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6937–6941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber J D, Taylor L J, Roussel M F, Sherr C J, Bar-Sagi D. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:20–26. doi: 10.1038/8991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roop D R, Lowy D R, Tambourin P E, Strickland J, Harper J R, Balaschak M, Spangler E F, Yuspa S H. Nature (London) 1986;323:822–824. doi: 10.1038/323822a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Missero C, Di Cunto F, Kiyokawa H, Koff A, Dotto G P. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3065–3075. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weber J D, Jeffers J R, Rehg J E, Randle D H, Lozano G, Roussel M F, Sherr C J, Zambetti G P. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2358–2365. doi: 10.1101/gad.827300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cowley S, Paterson H, Kemp P, Marshall C J. Cell. 1994;77:841–852. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt M, Goebeler M, Posern G, Feller S M, Seitz C S, Brocker E B, Rapp U R, Ludwig S. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41011–41017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donehower L A, Harvey M, Slagle B L, McArthur M J, Montgomery C A, Jr, Butel J S, Bradley A. Nature (London) 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng C, Zhang P, Harper J W, Elledge S J, Leder P. Cell. 1995;82:675–684. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lohrum M A, Ashcroft M, Kubbutat M H, Vousden K H. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:179–181. doi: 10.1038/35004057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Midgley C A, Desterro J M, Saville M K, Howard S, Sparks A, Hay R T, Lane D P. Oncogene. 2000;19:2312–2323. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Honda R, Yasuda H. EMBO J. 1999;18:22–27. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hennings H, Shores R, Mitchell P, Spangler E F, Yuspa S H. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:1607–1610. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.11.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kemp C J, Sun S, Gurley K E. Cancer Res. 2001;61:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamijo T, Bodner S, van de Kamp E, Randle D H, Sherr C J. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2217–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olson M F, Paterson H F, Marshall C J. Nature (London) 1998;394:295–299. doi: 10.1038/28425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evan G, Littlewood T. Science. 1997;281:1317–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]