Abstract

We previously reported that chick anterolateral endoderm (AL endoderm) induces cardiomyogenesis in mouse embryoid bodies. However, the requirement to micro-dissect AL endoderm from gastrulation-stage embryos precludes its use to identify novel cardiomyogenic factors, or to scale up cardiomyocyte numbers for therapeutic experiments. To circumvent this problem we have addressed whether human definitive endoderm (hDE) cells, which can be efficiently generated in large numbers from human embryonic stem cells (hESCs), can mimic the ability of AL endoderm to induce cardiac myogenesis. Results demonstrate that both hDE cells and medium conditioned by them induce cardiac myogenesis in pluripotent hESCs, as indicated by rhythmic beating and immunohistochemical/quantitative polymerase chain reaction monitoring of marker gene expression. The cardiomyogenic effect of hDE is enhanced when pluripotent hESCs are preinduced to the mes-endoderm state. Because this approach is tractable and scalable, it may facilitate identification of novel hDE-secreted factors for inclusion in defined cardiomyogenic cocktails.

Introduction

Stem cells capable of repairing damaged or diseased organs provide an attractive choice for transplantation. A major target for regenerative medicine is heart disease, an affliction representing 500,000 new cases and half as many deaths annually in the United States alone. In nearly all instances, cardiac insufficiency caused by cardiomyocyte death is irreversible because cardiomyocytes cannot restore damaged myocardium. Transplantation studies utilizing a variety of stem cell types, ranging from adult stem cells for autologous transplantation in human subjects, to pluripotent embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in animal models, have indicated that while this therapy modestly improves cardiac function, benefit is transient. Moreover, while histological evaluation of transplanted hearts has revealed evidence of revascularization, evidence of remuscularization is meager [1,2].

The replacement of muscle tissue in injured/diseased myocardium constitutes a major challenge. Resolution of this problem via transplantation will require transplantable numbers (tens of millions) of a cell type that confers remuscularization. Selection of a cell type specified to an early stage within the cardiomyogenic lineage may be ideal, since this would theoretically enable expansion and terminal differentiation of transplanted cells as they functionally integrate with host myocardium. Although resident cardiac adult stem cells may fulfill this criterion, whether these can be expanded to numbers sufficient for muscular restoration constitutes a formidable challenge [3]. On the other hand, pluripotent ESCs are theoretically available in unlimited numbers. The attractiveness of pluripotent stem cells as a therapeutic source was recently enhanced by the ability to induce skin fibroblasts into pluripotent stem (induced pluripotent stem cell) cells, thereby obviating ethical issues while providing patient-matched cells that are not rejected by the immune system [4,5].

Before pluripotent cells can be used for myocardial remuscularization, they must be induced to a differentiative endpoint that satisfies the dual requirement of avoiding tumor development while ensuring differentiation into the cardiomyogenic lineage. As a first step toward fulfilling this objective, we have taken an approach based on developmental cues that govern heart development in the early embryo. In accord with findings in this and other laboratories that the embryonic heart is induced by anterolateral endoderm (AL endoderm) [6], we previously reported that chick AL endoderm, or medium conditioned by it, could induce mouse embryoid bodies (EBs) to differentiate into cardiomyocytes with high efficiency [7]. However, the laborious requirement to micro-dissect explants from early-stage embryos to induce cardiomyogenesis in target cells severely restricts application of this approach. To circumvent this problem we have begun to evaluate the potential of human definitive endoderm (hDE) cells derived from pluripotent cells [8–10] to induce cardiomyogenesis. We report here that human hDE cells, or medium conditioned by them, can induce cocultured pluripotent human ESCs (hESCs), and especially mes-endodermal cells, into the cardiomyogenic lineage.

Materials and Methods

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts

Three days before culturing hESCs, 5×105 mitomycin-C-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were distributed to ten 60 mm cell culture dishes (18,000 cells/cm2) precoated with 0.1% gelatin (Millipore ES-006-B). MEFs were maintained in MEF growth medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (D-MEM, Millipore SLM-021-B) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen 16000-044), nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen 11140-050), and pen-strep (Invitrogen 15140-148).

Maintenance and passaging of pluripotent hESCs

H9 (WA09) hESCs were obtained from the National Stem Cell Bank (NSCB; WiCell). To maintain pluripotency hESCs were cultured on MEF feeders using hESC growth medium consisting of D-MEM/F-12 (Invitrogen 11330-032) supplemented with 20% Knockout Serum Replacement (Invitrogen 10828-028), 1 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen 25030-081), 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma M-6250), 1× nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen 11140-050), 4 ng/mL recombinant human fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-basic (amino acids 1-155; Invitrogen PHG0263), and 1× pen-strep (Invitrogen 15140-148). Pluripotent hESCs on MEF feeders were maintained under low oxygen (4% O2/5% CO2). Cells were replenished with fresh prewarmed hESC medium on a daily basis. hESCs were passaged every 7 days or earlier pending evidence of differentiation. To passage, hESC medium was replaced and colonies were scored to create 200 μm×200 μm squares using a StemPro EZPassage Tool (Invitrogen 23181-010). To avoid passaging differentiating cells, squares containing clumps of pluripotent cells were gently dislodged with a pipet tip and harvested with the medium. Clumps of pluripotent cells were diluted with hESC medium to achieve a 1:10 split and immediately replated on MEF feeder plates.

Induction of hDE differentiation in hESCs

Phases of the differentiation protocol are depicted in Fig. 1. Phase 1 was initiated by passaging 50%–70% confluent pluripotent hESCs growing on MEFs at a 1→3 split, into wells of a 12-well plate without feeders that had been precoated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences 356230). Precoating was performed by adding 0.2 mL Matrigel (83 μg/mL) in ice-cold D-MEM/F12 to each well for 30 min, followed by aspiration and air-drying. Pluripotency, in the absence of MEF feeders, was maintained by MEF-conditioned hESC medium, which was prepared by placing fresh hESC medium containing basic FGF (bFGF; 4 ng/mL) in culture dishes containing MEFs under normoxic conditions for 24 h and removing cell debris by filtration. During phase 1, hESCs were expanded under low oxygen in MEF-conditioned hESC medium for 7 days, during which time medium was replaced daily.

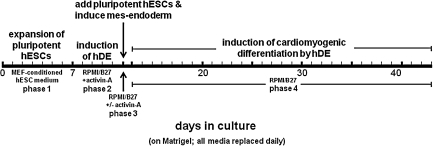

FIG. 1.

Scheme depicting experimental sequence for inducing hDE, then inducing cardiomyogenic differentiation in hESCs. hDE, human definitive endoderm cells; hESCs, human embryonic stem cells; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast.

After 7 days, pluripotent hESCs growing on Matrigel in MEF-conditioned hESC medium attained ∼95% confluency. At that time, phase 2 (Fig. 1) was initiated by inducing pluripotent hESCs into DE (hDE) by changing to defined medium consisting of Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) Medium 1640 (Invitrogen 22400) fortified with B-27 serum-free supplement (Invitrogen 17504-044), plus 100 ng/mL human recombinant activin-A (R&D Systems 338-AC). Activin-A-induced hDE differentiation was allowed to proceed for 5 days (phase 2, Fig. 1), during which time RPMI/B-27 with activin-A was replenished on a daily basis.

Induction of cardiomyogenesis in pluripotent ESCs by hDE cells

After 5 days' induction of hDE with activin-A, pluripotent hESCs growing in a separate dish under hypoxic conditions were prepared for cardiomyogenic induction by exchanging hESC medium for RPMI/B-27 (without activin-A), dissociation into 200 μm2 clumps, and seeding into the 12-well plates containing hDE at a 1→3 split. After a brief period to allow pluripotent hESC clumps to adhere to the hDE substrate, the medium was changed to either fresh RPMI/B-27, or to RPMI/B-27 containing 100 ng/mL activin-A for 24 h to induce mes-endoderm [8–10]. This 24-h period constitutes phase 3 (Fig. 1). After 24 h, all cocultures were replenished with fresh RPMI/B-27 without supplement. During the next 28–31 days (phase 4 in Fig. 1), cultures were monitored daily for evidence of cardiomyogenic differentiation. Medium in all dishes was exchanged with fresh RPMI/B-27 on a daily basis.

Induction of cardiomyogenesis in pluripotent ESCs by hDE-conditioned medium

The experimental design to assess whether hDE-conditioned medium (hDE-cm) could replace the cardiomyogenic effect of hDE cells is depicted in Fig. 5A. In these experiments, pluripotent hESCs were expanded without feeders in MEF-conditioned hESC medium for the initial 7-day period (phase 1), followed by treatment for 24 h with RPMI/B-27 without or with activin-A (100 ng/mL) to induce mes-endoderm; hence, the 5-day period (phase 2 in Fig. 1) to induce hDE cells was omitted. For the next 28–31 days cells were treated with RPMI/B-27 that had been conditioned by hDE cells for exactly 24 h; this constitutes hDE-cm. During the ensuing 28–31-day period, the medium was replaced on a daily basis with hDE-cm that had been conditioned during the previous 24-hr period.

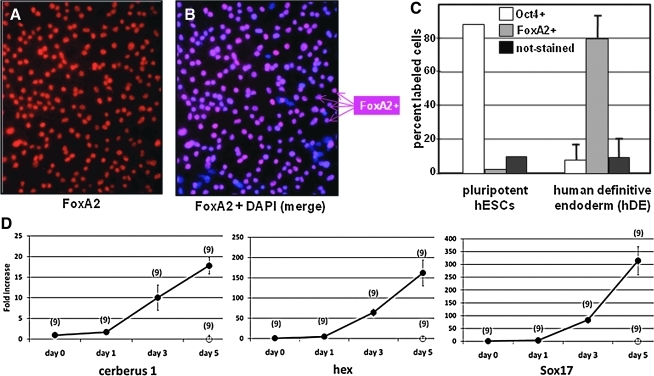

FIG. 5.

Medium conditioned by hDE-cm induces cardiac myogenesis. Panel (A) depicts the experimental scheme. This process differs from that used for the experiments described in Figs. 1–4 in that induction of hDE cells was omitted (days 7–12), replaced by induction of cardiomyogenesis with hDE-cm at day 13. Panels (B) and (C) show ImageJ quantitation of the area in each well occupied by cardiomyocytes (MHC-positive cells). Panel (B) illustrates the inductive effect of hDE-cm, in comparison with RPMI/B27 alone, on pluripotent hESCs; panel (C) illustrates that the inductive effect of hDE-cm on mes-endoderm (+activin-A 24 h) is significantly more pronounced than on pluripotent hESCs (no activin-A). Panel (D) shows real-time (qPCR) analyses of gene expressions in pluripotent cells that were preinduced with activin-A and induced with hDE-cm. Error bars=± SEM; numbers above each bar indicate the number of cultures that were evaluated. P values indicated statistically significant differences (Student's t-test). hDE-cm or cm, medium conditioned by human definitive endoderm cells; R/B, RPMI/B27; MHC, α-myosin heavy chain; cTnT, cardiac troponin-T; TEK, endothelial tyrosine kinase; VE-cad, VE-cadherin; smMHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain; CNN1, calponin-1; VE, visceral endoderm.

Immunohistochemistry

Differentiation of hDE was monitored by expression of the hDE marker HNF3β using an anti-FoxA2 (hepatocyte nuclear factor 3β [HNF3β]) antibody (Santa Cruz 6554, goat polyclonal diluted 1:200). Pluripotency was evaluated by immunostaining Oct4 (Santa Cruz sc-9081, rabbit polyclonal diluted 1:200). The medium was removed and cells were gently rinsed 3× with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 15 min fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, 15 min incubation with 0.5% Triton-X-100, and 30 min blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS. The primary antibodies were applied in 1% BSA/PBS overnight. After washing, the secondary antibodies—donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen A21206) and donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen A11057)—were applied in 1% BSA/PBS (1:1,000) for 1 h. The extent of hDE differentiation was determined by enumerating percentages of FoxA2-positive cells in the cellular monolayer.

Differentiation of cardiac myocytes was monitored by expression of myosin heavy chain (MHC) using a monoclonal antibody (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank MF20). Cells were treated as above except that fixation was with 100% ice-cold methanol for 2 h followed by rehydration and 30 min blocking using block serum-free (Dako×0909). The primary antibody was applied in Dako Antibody Diluent (1:60; S0809) overnight. After washing, the secondary antibody, donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen A21203), was applied in Dako Antibody Diluent (1:750) for 1 h.

Quantification of immunofluorescence

Because cardiomyocytes differentiate in multilayered clusters, it was necessary to estimate the extent of cardiomyocyte differentiation using digital image analysis, in which the area occupied in MHC-positive cells in cell culture dishes was quantified. For each condition evaluated, a minimum of 20 randomly selected 100× images were photomicrographically captured from each culture dish. Digital quantification was performed using ImageJ software [11], which is available from the NIH (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/nih-image/about.html). To ensure arbitrary evaluation and reproducibility, the same exposure settings were used to analyze cultures grown under all experimental conditions. Using digital subtraction, areas with positive fluorophor emission at 594 nm were outlined, using a consistent minimum intensity threshold; only those pixelated areas meeting the minimum intensity threshold were used in making these calculations. Areas of fluorescence that did not occupy a minimum contiguous area were excluded, to remove digital noise and aberrant fluorescence. The area calculated to be occupied by true fluorescent signal by this digital subtraction was compared with total image pixels to generate area percentages.

Nuclei were counter stained with 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (500 ng/mL in distilled water [DW]), which was applied for 5 min at room temperature followed by three 2 min rinses with Tris-buffered saline (25mM Tris/150mM NaCl/2mM KCl pH 7.4) (TBS).

Radioactive semi-quantitative reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction

Cultures were lysed and RNA was purified using Qiagen RNeasy Plus (Qiagen 73134). For each sample, 500 ng total RNA determined by A260 was reverse-transcribed in a final reaction volume of 20 μL using iScript (BioRad 170-8891). Radioactive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using equal aliquots of reverse-transcription (RT) product as template in GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega M7123) supplemented with 1 μCi 32P-dATP per sample. The following primer pairs were included in the reaction mixture at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/mL—MYH7 (βMHC): forward 5′-AGATGGATGCTGACCTGTCC-3′, reverse 5′-GGTTTTTCCTGTCCTCCTCC-3′; NKX2-5 (Nkx2.5); forward 5′-GGTCTATGAACTGGAGCGGC-3′, reverse 5′-ATAGGCGGGGTAGGCGTTAT-3′; GAPDH: forward 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′, reverse 5′-ACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC-3′. PCR was performed using a 10 min hot start (94°C) followed by 35 cycles of 60 s melt (94°C), 45 s annealing (60°C), and 45 s elongation (72°C). Autorads were obtained by phosphorimaging.

Real-time PCR

Cultures were lysed and RNA was purified and reverse-transcribed as described above. Quantitative (q) PCR was performed on a BioRad iCycler using a hot start followed by alternating steps of annealing/elongation (60 s at 60°C) and denaturation (15 s at 95°C). Each reaction was performed in 25 μL final volume containing 12.5 μL RT2 qPCR master mix (SABiosciences PA-011), 10.5 μL nuclease-free DW, 1.0 μL cDNA template, and 1.0 μL of one of the following proprietary SABiosciences qPCR-certified primer pairs to amplify the following human genes: CDH5 (VE-cadherin 5, SAB PPH00668E); CER1 (cerberus 1, SAB PPH01927B); CNN1 (calponin 1, SAB PPH02065A); GUSB (glucuronidase-β, SAB PPH01096E); HHEX (Hex, SAB PPH11416A); MYH6 (α-MHC, SAB PPH02439A); MYH11 [smooth muscle (sm) MHC, SAB PPH02469A]; NKX2-5 (Nkx2.5, SAB PPH02462A); SOX17 (SRY-box 17, SAB PPH02451A); TEK (endothelial cardiac tyrosine kinase, SAB PPH00795B); TNNT2 (troponin-T type 2, SAB PPH02619A).

Statistical methods

Within each experiment, each experimental condition was evaluated from wells plated in triplicate. “N” was increased by performing 3 experiments in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined using a 2-tailed equal variance Student's t-test at the 95% confidence limit.

Results

Induction of hDE

Previous studies have shown that endoderm explanted from embryos [7], or endoderm-derived murine cell lines, can induce cardiomyogenesis in pluripotent ESCs [12–16]. The goal of this study was to extend this principle by establishing an all-human system, using endoderm cells that can be generated in large numbers under defined cell culture conditions. Figure 1 depicts the overall experimental scheme for cardiomyogenic induction by hDE, which is divided into 4 phases. After expansion of pluripotent cells under feeder-free conditions in phase 1, hDE is induced in phase 2, followed by implantation of pluripotent hESCs and induction of mes-endoderm (phase 3), and finally endoderm-induced differentiation into the cardiomyogenic lineage (phase 4).

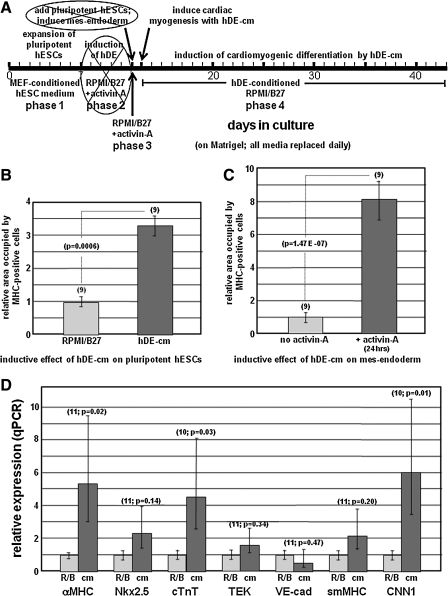

The approach employed in phase 2 to induce a “feeder layer” of hDE was based on recently described methods wherein 5 days' treatment with activin-A induces differentiation of pluripotent hESCs into hDE [8,9]. Using this approach, pluripotent hESCs differentiate into a near-homogeneous monolayer of DE cells. Immunostaining shown in Fig. 2 (A, B) revealed that the percentage of cells expressing the DE marker FoxA2 increased from nil to >80%, concomitant with downregulation of the pluripotent marker Oct4 from >80% to <10% (Fig. 2C), during the 5-day induction. Identity of the FoxA2-positive cells as definitive embryonic endoderm, rather than primitive endoderm, was confirmed by the absence of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) expression (not shown). These findings were complemented by qPCR determinations to assess the endoderm marker sox17, as well as the endoderm markers hex and cerberus, which have been associated with cardiomyogenic induction [17]. As shown in Fig. 2D, Sox17 increased >300-fold after 5 days' induction with activin-A, during which time the expression of cerberus-1 and hex, respectively, increased >15- and 150-fold. Parallel wells containing pluripotent cells that were not induced with activin-A were also evaluated, indicating that expression of these genes after 5 days was at or below the levels shown for day 0 in panel D (not shown).

FIG. 2.

Induction of hDE by activin-A. Panels (A) and (B) show the same monolayer of cultured pluripotent H9 hESCs after 5 days' treatment with 100 ng/mL activin-A. The cells in (A) were immunostained with an antibody specific for FoxA2, a marker for definitive endoderm. (B) Displays all nuclei in the culture per staining with DAPI. Panel (C) quantitatively describes the result after 5 days' induction with activin-A, wherein cells in random fields of each culture were scored for expression Oct4 (not shown) or FoxA2. Each bar indicates the average of 2 independent experiments, in each of which >5,000 cells were evaluated; error bars denote±SEM. Panel (D) shows results from real-time qPCR analysis of marker gene expression during the 5-day period of hDE induction with activin-A (filled symbols); cells not treated with activin-A are denoted by open symbols. The number of wells evaluated is shown in parentheses; vertical bars indicate±SEM. SEM, standard error of the mean; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; DAP1, 4′6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Induction of cardiomyogenesis by hDE

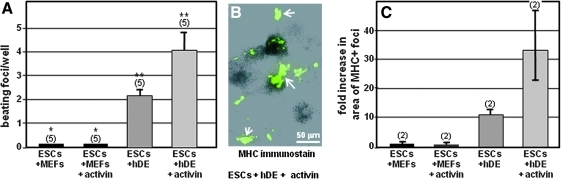

It was then determined whether a feeder layer consisting of hDE could induce roller-generated clumps of implanted pluripotent hESCs into the cardiomyogenic pathway. In these experiments the cardiomyogenic efficacy of hDE cells was compared with that of MEFs, which were selected for comparison because in the absence of pluripotency maintenance factors, MEFs support the spontaneous differentiation of various cell types. Clumps of pluripotent hESCs were seeded onto established monolayers of hDE or MEF feeder cells. In these experiments it was also of interest to ascertain whether cells at a selected stage of the differentiative pathway are more predisposed toward cardiomyogenic induction than pluripotent hESCs. Therefore, as indicated for phase 3 in Fig. 1, in some experiments the implanted hESCs were pretreated with 100 ng/mL activin-A for 24 h, which has been shown to induce mes-endoderm [18]. Thereafter (phase 4 in Fig. 1), cultures were maintained in defined medium (RPMI/B-27) without growth factors, with daily monitoring for appearance of rhythmically beating cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, hESCs plated on MEFs (ESCs/+MEFs) exhibited no beating. By contrast, rhythmically beating cells appeared when hESCs were seeded onto hDE (Fig. 3A: ESCs/+hDE). Moreover, hESCs treated with activin-A for 24 h (phase 3 in Fig. 1) to induce mes-endoderm (Fig. 3A: ESCs/+hDE/+activin) displayed increased numbers of beating foci.

FIG. 3.

Human definitive endoderm, but not MEFs, induces formation of rhythmically beating clusters in pluripotent hESCs. hDE was induced in H9 ESCs as described in the Materials and Methods section. Pluripotent hESCs were seeded onto either a hDE feeder layer, or onto an MEF feeder layer (control), with and without 1 additional day of activin-A treatment (+activin) to induce mes-endoderm. RPMI/B-27 medium was exchanged daily. Panel (A) shows the average number of beating foci. Vertical bars=± SEM; bars denoted “*” and “**” are statistically significant at P<0.05. Panel (B) is an immunostain for myosin heavy chain, showing the presence of differentiated cardiomyocyte clusters (arrows). Panel (C) shows the relative areas occupied by MHC-positive cells. Vertical bars=± SEM. MHC, myosin heavy chain; RPMI, Roswell Park Memorial Institute.

Cardiomyocyte identity was corroborated by immunostaining MHC at the end of the culture period. As shown in Fig. 3B this revealed cardiomyogenic foci as various sized, randomly dispersed clusters of multilayered cells; isolated cardiomyogenic cells were never observed. Because MHC-positive cells were present in dense multilayers, extent of cardiomyogenic differentiation was quantified by determining the area occupied by MHC-positive cells in each well, using ImageJ [11] as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 3C, this revealed that in comparison with wells containing hESCs grown on MEFs, wells containing hESCs cultured on hDE exhibited an ∼11-fold increase in cardiomyogenic area. Moreover, inclusion of activin-A for the initial 24 h of hESC growth to induce mes-endoderm resulted in a >30-fold increase in cardiomyogenic area (Fig. 3C). To summarize, the results shown in Fig. 3 indicate that hDE cells induce pluripotent hESCs to differentiate into cardiac myocytes, and that this effect is enhanced by pretreating hESCs with activin-A to induce mes-endoderm.

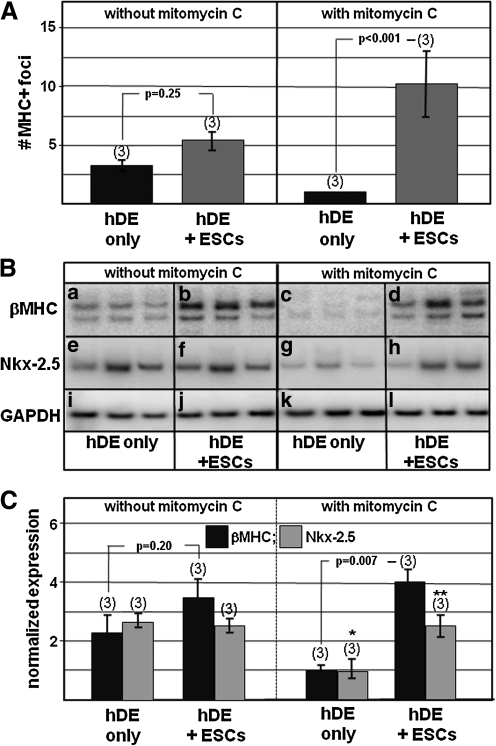

During these experiments it was noted that cultures of hDE only, without hESCs, could also produce cardiomyocytes (not shown). This was interpreted to mean that although 5 days' treatment with activin-A induced hDE in 80% of cells (Fig. 2), some cells in the remaining 20% were cardiomyogenically induced by the hDE. It was therefore important to distinguish whether cardiomyocytes in Fig. 3 originated from the monolayer of hDE feeder cells, or from the seeded clumps of pluripotent hESCs. To address this issue, experiments were performed in which the inductive hDE cells were pretreated with mitomycin-C, an approach previously used to confirm induction of islet-1-positive adult stem cells by cardiac mesenchymal cells [19]. As shown in Fig. 4A, treatment with mitomycin-C inhibited cardiomyogenesis within hDE (only) monolayers; moreover, the extent of cardiomyogenesis supported by hDE treated with mitomycin-C was increased. Semi-quantitative RT/PCR corroborated these results (Fig. 4B, C).

FIG. 4.

Mitomycin-C inhibits cardiomyogenesis in hDE, without inhibiting its ability to induce cardiomyogenesis in cocultured pluripotent hESCs. Cultures were treated as described in Fig. 1 except that hDE was pretreated with mitomycin C (see the Materials and Methods section) before being seeded with pluripotent hESCs. At the end of the culture period, cells were either immunostained for MHC or processed for RT/PCR. Panel (A) depicts the extent of MHC-positive clusters in cultures that were not treated (left) or treated (right) with mitomycin-C. Panel (B) shows results of semi-quantitative (radioactive) RT/PCR determinations. Panel (C) quantitatively summarizes the RT/PCR results in panel (B). In panels (A) and (C) the number of wells grown under each condition is noted in parentheses; vertical bars=± SEM. In (C), the P value between bars labeled “*” and “**” is 0.05. RT/PCR, reverse transcription/polymerase chain reaction.

Cardiomyogenesis is induced by medium conditioned by hDE cells

To reduce complexity of the hDE-hESC coculture system, and to further verify that cardiomyogenesis was induced in implanted hESCs rather than in residual pluripotent cells in the hDE monolayer, it was assessed whether RPMI/B27 medium conditioned by hDE cells—hereafter hDE-cm—could, similar to hDE cells, induce cardiomyogenesis in pluripotent hESCs. For these experiments, hDE-cm was obtained by conditioning RPMI/B-27 medium with hDE for exactly 24 h, followed by direct application to hESCs (see scheme, Fig. 5A). In these experiments, pluripotent hESCs were expanded for 7 days, followed in some instances (as in Fig. 5C and D) by treatment with 100 ng/mL activin-A for 24 h to induce mes-endoderm. The cells were then provided hDE-cm, which was replaced daily. After 28 days, cardiomyogenic differentiation was evaluated by immunohistochemical (Fig. 5B, C) and qPCR (Fig. 5D) analyses. Figure 5B shows that in comparison with fresh RPMI/B27, cultivation of pluripotent hESCs in hDE-cm significantly increased the extent of MHC expression. Figure 5C shows that preinduction to mes-endoderm augmented this response, resulting in an 8-fold cardiomyogenic induction by hDE-cm. Increased expression of MHC detected by immunohistochemistry was corroborated by qPCR, revealing significantly increased expression of cardiomyogenic mRNAs (Fig. 5D), including α-MHC and cTnT. Although expression of Nkx2.5 and smMHC, which are also expressed during early cardiomyogenesis, was also increased, these were not statistically significant; however, a significant increase in expression of the smooth muscle gene CNN1 was observed. In contrast, the endothelial cell markers TEK and VE-cad were unaffected.

Discussion

These results indicate that, similar to endoderm isolated from embryos or endoderm cell-lines, hDE generated from hESCs can induce cardiomyogenesis in human pluripotent ESCs. This effect is more pronounced when pluripotent cells are predifferentiated to mes-endoderm. Medium conditioned by hDE cells (hDE-cm) also has cardiomyogenic efficacy. The effect of hDE-cm may be selective for cardiomyocytes, since endothelial cell markers TEK and VE-cad are unaffected (Fig. 5D). Although the smooth muscle markers smMHC and calponin-1 are also increased by hDE, these genes are expressed during early stages of cardiac myocyte differentiation in the embryo.

It is interesting to compare the potency of hDE with other cardiomyogenic inducers. AL endoderm from gastrulation-stage embryos is essential for terminal cardiomyogenic differentiation of cocultured precardiac mesoderm [20,21]. AL endoderm can also respecify cells in the posterior primitive streak or posterolateral mesoderm (PL mesoderm), from a hemangiogenic to a cardiomyogenic fate [22]. We recently reported that chick AL endoderm potently induces cardiac myogenesis in mouse EBs, all of which exhibited rhythmic beating [7]. Although head-to-head determinations have not been performed, these findings support the notion that, among endodermal cardiomyogenic inducers, AL endoderm is the most potent. Unfortunately, paucity of this tissue, which is isolated by microscopic dissection from gastrulation-stage animal embryos, prevents the ability to characterize cardiomyogenic factors or to scale-up ESC-derived cardiomyocytes for experimental therapeutics.

Other laboratories have utilized readily obtained in vitro-generated surrogates of AL endoderm, especially murine endodermal cell lines. In one study, secretory products of END-2 cells, a VE-like cell-line derived from mouse teratocarcinoma [23], were shown to induce ∼20% enriched cardiomyocytes in pluripotent hESCs [13,14]. Because we were unable to dissociate cardiomyocytes from multilayered clusters, enumeration of cardiomyocyte percentages induced by hDE was not possible. Hence, although we cannot compare the relative efficacies of hDE and END-2 cells, these both appear to be less potent than embryonic AL endoderm. The relatively modest inductive effect of hDE reported here may indicate that DE has less cardiomyogenic potency than VE, as recently reported using the mouse system [12,16]; we are currently preparing VE from pluripotent cells to examine this possibility in the human system. Although AL endoderm explanted from embryos appears to be more cardiomyogenic than that of cultured endoderm cells, it must be kept in mind that, with the exception of our recent study using mouse EBs [7], studies employing AL endoderm addressed its effect on gastrulation-stage target tissues [21,22], in contrast to this and other studies wherein inductive effects of cultured hDE and mouse endoderm cell-lines [13] were assessed on pluripotent cells. It will be interesting to see how cells positioned at early stages within the cardiomyogenic lineage, or within other mesodermal pathways, respond to cardiomyogenic signals from hDE and/or hVE; in this regard, our results consistently revealed that the response of mes-endoderm to hDE-cm was more robust than that of pluripotent ESCs.

Although AL endoderm is comprised of DE the finding that AL endoderm and hDE have dissimilar cardiomyogenic potency is not surprising, since AL endoderm is regionally distinct in its ability to induce cardiomyogenesis. For example, whereas AL endoderm potently induces cardiomyogenesis in adjacent as well as ectopic postgastrulation mesoderm, posterolateral (PL) endoderm cannot induce cardiomyogenesis in any of these targets [7,21,22]. Evidence that AL endoderm is regionally patterned has been demonstrated by findings that chick DE consists of 2 subpopulations comprised of anterior and posterior regions that, respectively, express Sox17 and GATA6 [24]. The concept that DE must be regionally specialized to induce cardiomyogenesis is also consistent with the temporo-spatial expression pattern of known cardiomyogenic molecules, including, Cerberus, hex, and BMP2-4/FGF8 [25–28], all of which are expressed in AL endoderm adjacent to the heart-forming region in the embryo. It is therefore possible that, similar to the differential effects recently ascribed to DE and VE [12,16], the modest cardiomyogenic potency of hDE, in comparison with AL endoderm, reflects the relatively nonspecialized status of hDE when generated in homogeneous cell culture. Other factors may contribute to the relatively modest induction efficiency of hDE described here; for example, these determinations were performed in defined medium consisting of RPMI/B27, the B27 component of which contains a large quantity of insulin, which was recently shown to inhibit cardiomyocyte differentiation in pluripotent cells [29]. We are evaluating this and other possibilities, including the identification and characterization of inhibitory as well as inductive cardiomyogenic factors within the human endoderm secretome, for comparison with the recently published secretome of END-2 cells [15]. With this information we hope to attain the ultimate objective of improving the efficiency of currently employed cardiomyogenic protocols [30–32].

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by NIH HL089471.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gnecchi M. Zhang Z. Ni A. Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1204–1219. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Passier R. van Laake LW. Mummery CL. Stem-cell-based therapy and lessons from the heart. Nature. 2008;453:322–329. doi: 10.1038/nature07040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans SM. Mummery C. Doevendans PA. Progenitor cells for cardiac repair. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J. Vodyanik MA. Smuga-Otto K. Antosiewicz-Bourget J. Frane JL. Tian S. Nie J. Jonsdottir GA. Ruotti V, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K. Tanabe K. Ohnuki M. Narita M. Ichisaka T. Tomoda K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lough J. Sugi Y. Endoderm and heart development. Dev Dyn. 2000;217:327–342. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200004)217:4<327::AID-DVDY1>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudy-Reil D. Lough J. Avian precardiac endoderm/mesoderm induces cardiac myocyte differentiation in murine embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:e107–e116. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134852.12783.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLean AB. D'Amour KA. Jones KL. Krishnamoorthy M. Kulik MJ. Reynolds DM. Sheppard AM. Liu H. Xu Y. Baetge EE. Dalton S. Activin a efficiently specifies definitive endoderm from human embryonic stem cells only when phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling is suppressed. Stem Cells. 2007;25:29–38. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Amour KA. Agulnick AD. Eliazer S. Kelly OG. Kroon E. Baetge EE. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasunaga M. Tada S. Torikai-Nishikawa S. Nakano Y. Okada M. Jakt LM. Nishikawa S. Chiba T. Era T. Induction and monitoring of definitive and visceral endoderm differentiation of mouse ES cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1542–1550. doi: 10.1038/nbt1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins TJ. ImageJ for microscopy. Biotechniques. 2007;43:25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown K. Doss MX. Legros S. Artus J. Hadjantonakis AK. Foley AC. eXtraembryonic ENdoderm (XEN) stem cells produce factors that activate heart formation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passier R. Oostwaard DW. Snapper J. Kloots J. Hassink RJ. Kuijk E. Roelen B. de la Riviere AB. Mummery C. Increased cardiomyocyte differentiation from human embryonic stem cells in serum-free cultures. Stem Cells. 2005;23:772–780. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beqqali A. Kloots J. Ward-van Oostwaard D. Mummery C. Passier R. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of human embryonic stem cells differentiating to cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1956–1967. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrell DK. Niederlander NJ. Faustino RS. Behfar A. Terzic A. Cardioinductive network guiding stem cell differentiation revealed by proteomic cartography of tumor necrosis factor alpha-primed endodermal secretome. Stem Cells. 2008;26:387–400. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtzinger A. Rosenfeld GE. Evans T. Gata4 directs development of cardiac-inducing endoderm from ES cells. Dev Biol. 2010;337:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider VA. Mercola M. Spatially distinct head and heart inducers within the Xenopus organizer region. Curr Biol. 1999;9:800–809. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu H. Dalton S. Xu Y. Transcriptional profiling of definitive endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells. Comput Syst Bioinfor Conf. 2007;6:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moretti A. Caron L. Nakano A. Lam JT. Bernshausen A. Chen Y. Qyang Y. Bu L. Sasaki M, et al. Multipotent embryonic is l1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell. 2006;127:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antin PB. Taylor RG. Yatskievych T. Precardiac mesoderm is specified during gastrulation in quail. Dev Dyn. 1994;200:144–154. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugi Y. Lough J. Anterior endoderm is a specific effector of terminal cardiac myocyte differentiation of cells from the embryonic heart forming region. Dev Dyn. 1994;200:155–162. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultheiss TM. Xydas S. Lassar AB. Induction of avian cardiac myogenesis by anterior endoderm. Development. 1995;121:4203–4214. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mummery CL. Feijen A. van der Saag PT. van den Brink CE. de Laat SW. Clonal variants of differentiated P19 embryonal carcinoma cells exhibit epidermal growth factor receptor kinase activity. Dev Biol. 1985;109:402–410. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90466-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chapman SC. Matsumoto K. Cai Q. Schoenwolf GC. Specification of germ layer identity in the chick gastrula. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman SC. Schubert FR. Schoenwolf GC. Lumsden A. Analysis of spatial and temporal gene expression patterns in blastula and gastrula stage chick embryos. Dev Biol. 2002;245:187–199. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yatskievych TA. Pascoe S. Antin PB. Expression of the homebox gene Hex during early stages of chick embryo development. Mech Dev. 1999;80:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bort R. Martinez-Barbera JP. Beddington RS. Zaret KS. Hex homeobox gene-dependent tissue positioning is required for organogenesis of the ventral pancreas. Development. 2004;131:797–806. doi: 10.1242/dev.00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alsan BH. Schultheiss TM. Regulation of avian cardiogenesis by Fgf8 signaling. Development. 2002;129:1935–1943. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freund C. Ward-van Oostwaard D. Monshouwer-Kloots J. van den Brink S. van Rooijen M. Xu X. Zweigerdt R. Mummery C. Passier R. Insulin redirects differentiation from cardiogenic mesoderm and endoderm to neuroectoderm in differentiating human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:724–733. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laflamme MA. Chen KY. Naumova AV. Muskheli V. Fugate JA. Dupras SK. Reinecke H. Xu C. Hassanipour M, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang L. Soonpaa MH. Adler ED. Roepke TK. Kattman SJ. Kennedy M. Henckaerts E. Bonham K. Abbott GW, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kattman SJ. Witty AD. Gagliardi M. Dubois NC. Niapour M. Hotta A. Ellis J. Keller G. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]