Abstract

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevailing health problem that severely impacts quality of life. Because SUI is mainly due to urethral sphincter deficiency, several preclinical and clinical trials have investigated whether transplantation of patient's own skeletal muscle–derived cells (SkMDCs) can restore the sphincter musculature. The specific cell type of SkMDCs has been described as myoblasts, satellite cells, muscle progenitor cells, or muscle-derived stem cells, and thus may vary from study to study. In more recent years, other stem cell (SC) types have also been tested, including those from the bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, and adipose tissue. These studies were mostly preclinical and utilized rat SUI models that were established predominantly by pudendal or sciatic nerve injury. Less frequently used animal models were sphincter injury and vaginal distension. While transurethral injection of SCs was employed almost exclusively in clinical trials, periurethral injection was used in all preclinical trials. Intravenous injection was also used in one preclinical study. Functional assessment of therapeutic efficacy in preclinical studies has relied almost exclusively on leak point pressure measurement. Histological assessment examined the sphincter muscle content, existence of transplanted SCs, and possible differentiation of these SCs. While all of these studies reported favorable functional and histological outcomes, there are questions about the validity of the animal model and claims of multilineage differentiation. In any event, SC transplantation appears to be a promising treatment for SUI.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) afflicts more than 200 million people worldwide [1]. In the United States 17 million people were estimated to have this condition and the total annual cost of UI and associated conditions was estimated to range up to 32 billion dollars [2]. UI is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men up to age 80, after which it affects the sexes equally [3]. Approximately 50% of women older than 20 years have reported UI symptoms, and ∼50% of these reporting patients are classified as having the stress urinary incontinence (SUI). The remaining patients are classified as having either the urge type of UI (UUI, 16%) or mixed type (both SUI and UUI, 34%) [4]. UUI, defined as the involuntary loss of urine associated with a strong sensation to void, is related to detrusor overactivity (motor urgency) and hypersensitivity (sensory urgency). SUI, defined as the involuntary loss of urine in the absence of a detrusor contraction, occurs as a result of weakened muscles of the pelvic floor and the urethra, causing urine loss whenever there is an increase of abdominal pressure (eg, coughing, sneezing, or laughing). While primarily a female concern (due to pregnancy, childbirth, menopause, and hysterectomy), SUI can happen to men (mostly due to prostate surgery).

Pharmaceutical treatment of SUI has not been successful [5]. Periurethral injection of bulking agents (eg, bovine collagen) has poor long-term efficacy and is associated with complications such as voiding dysfunction, abscess formation, and pulmonary embolism [6,7]. More invasive procedures, such as sling surgery, are more efficacious but are associated with complications such as urinary track injury, bleeding, and infection [8]. Thus, alternative treatments, especially those that can restore natural continence mechanism, have been sought after. In this regard, stem cell (SC) therapy is presently considered as having the best chance to succeed.

Rationale for Using SC Therapy

Urine is continuously produced by the kidneys and flows to the bladder for storage. During this filling/storage phase, the lumen of the urethra is tightly shut. This leakage prevention mechanism is controlled by the urethra and a supportive apparatus that consists of the anterior vaginal wall and its surrounding muscles and fascial tissues [9]. The urethra is a multilayered structure that consists of striated muscle, smooth muscle, connective tissue, submucosal vascular plexus, and epithelium. While all of these tissues are important for the continence mechanism, the striated muscle has been shown to contribute the most [9]. In SUI patients and animal models, the urethral striated muscle is significantly reduced [10], and this decline roughly parallels the decline in the urethral closure pressure. Thus, if the lost striated muscle can be restored, amelioration of SUI can be expected. Likewise, while the smooth muscle plays a lesser role, it is still significantly reduced in SUI patients [9] and thus a desirable treatment target.

SCs have been shown to differentiate into striated and smooth muscle cells [11–13]. Therefore, their transplantation into the weakened urethra of SUI patients has the potential to replenish the depleted musculature. SCs also secrete a wide array of growth factors, some of which are angiogenic while others are musculotrophic [11–13]. Thus, through these paracrine actions, SCs can possibly augment both the urethral vasculature and musculature. Finally, intraurethral injection of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) into an SUI rat model has been shown to improve the urethral connective tissue [14], and this appears to be due to ADSC's ability to produce and process collagen and elastin [15].

Current Status

The initial concept of cell-based therapy for SUI was based on the hypothesis that injection of skeletal myoblasts into the weakened urethra could replenish the sphincter muscle [16]. It then evolved into substituting myoblasts with other types of skeletal muscle–derived cells (SkMDCs), including skeletal muscle–derived stem cells (SkMSCs). In 2002 Yiou et al. published the first preclinical study in which skeletal muscle precursor cells were used to treat a murine model of urethral sphincter injury [17] (Table 1). Since then and up to 2008, 10 additional preclinical and 4 clinical studies, all using SkMDCs, have been published. In January 2010, the first nonskeletal SC study was published in print form [14]; specifically, this study demonstrated the efficacy of ADSCs in treating SUI in a rat model. Meanwhile, a clinical investigation on the efficacy of ADSCs in treating postprostatectomy SUI in 2 patients was published in print form [18], but later retracted. In March of the same year another ADSC study was in print form [19], and in 2011, 2 others also became available [20,21]. During the same period (2010–2011), there have been 4 studies using bone marrow SCs (BMSCs), 2 studies using umbilical cord blood SCs (CBSCs), and 1 study using SkMSCs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stem Cell Trials for Stress Urinary Incontinence*

| Publication year/First author | Animal model/Patients | Cell type | Transplantation method/cell number | Cell tracking method | Assessment time point | Functional assessment | Urethral histology | Differentiation assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002/Yiou [17] | Sphincter injury mice | Autologous SkMSC | Periurethral/250,000 | PKH26 | 1 & 4 weeks | None | HE | None |

| 2003/Lee [42] | Sciatic nerve transection rats | Allogeneic SkMSC | Periurethral/3,000,000 | None | 1 & 4 weeks | LPP | HE, CD8 | None |

| 2003/Yiou [44] | Sphincter injury rats | Autologous SkMSC | Periurethral/5,000,000 | LacZ | 5 & 30 days | Sphincter electrostimulation | PGP9.5, AchR, β-gal | α-actinin-2 |

| 2003/Cannon [74] | Sciatic nerve transection rats | Allogeneic SkMSC | Periurethral/3,000,000 | None | 2 weeks | Organ bath | Myosin, CD4 | None |

| 2004/Chermansky [64] | Sphincter cauterization rats | Allogeneic SkMSC | Periurethral/1,500,000 | LacZ | 2, 4, & 6 weeks | LPP | HE, β-gal PGP9.5, Myosin | None |

| 2004/Lee [66] | Pudendal nerve transection rats | Allogeneic SkMSC | Periurethral/30,000,000 | None | 4 & 12 weeks | LPP | HE | None |

| 2005/Yiou [45] | Sphincter injury rats | Autologous SkMSC | Periurethral/5,000,000 | LacZ | 4 weeks | Sphincter electrostimulation | β-gal | α-actinin-2 |

| 2006/Kwon [65] | Sciatic nerve transection rats | Allogeneic SkMSC | Periurethral/1,000,000 | None | 4 weeks | LPP, Organ bath | HE | None |

| 2007/Kim [55] | Sciatic nerve transection nude rats | Human SkMSC | Periurethral/500,000 | Human lamins | 4 weeks | LPP | HE | None |

| 2007/Mitterberger [22] | 123 female patients | Autologous SkMSC | Transurethral/28,000,000 | NA | 1 year | Clinical, Urodynamic | NA | NA |

| 2008/Mitterberger [23] | 63 male patients | Autologous SkMSC | Transurethral/28,000,000 | NA | 1 year | Clinical, Urodynamic | NA | NA |

| 2008/Mitterberger [24] | 20 female patients | Autologous SkMSC | Transurethral/20,000,000 | NA | 1, 3, 6,12, & 24 months | Clinical, Urodynamic | NA | NA |

| 2008/Carr [28] | 8 female patients | Autologous SkMSC | Periurethral & Transurethral/20,000,000 | NA | 3–24 months | Clinical | NA | NA |

| 2008/Hoshi [53] | Periurethral injury rats | Allogeneic & Xenogeneic rodent SkMSC | Periurethral/Unknown cell number | GFP transgene | 4 & 12 weeks | Electrical stimulation | EM | SMA, N-200 |

| 2008/Furuta [54] | Pudendal nerve transection nude rats | Human SkMSC | Periurethral/1,000,000 | Human lamins | 6 weeks | LPP | IF for human lamins | None |

| 2010/Lin [14] | Vagina distension rats | Autologous ADSC | Periurethral & IV/1,000,000 | BrdU, EdU | 4 weeks | Conscious cystometry, LPP | Elastin, SDF-1, Trichrome | SMA |

| 2010/Fu [19] | Vagina distension rats | Allogeneic ADSC | Periurethral/4,500,000 | None | 1 and 3 months | LPP | None | None |

| 2010/Kinebuchi [48] | Sphincter injury rats | Autologous BMSC | Periurethral/500,000 | GFP | 1 to 12 weeks | LPP | HE, SMA, Myosin | Desmin, PGP9.5 |

| 2010/Lim [50] | Sphincter injury rats | Human CBSC | Periurethral/2,000,000 | Iron oxide & DiI | 2 & 4 weeks | LPP | HE, Trichrome | Desmin |

| 2010/Lee [29] | 39 female patients | Allogeneic CBSC | Periurethral/400,000,000 | NA | 1, 3, 12 months | Clinical, Urodynamic | NA | NA |

| 2010/Zou [49] | Sciatic nerve transection rats | BMSC on scaffold | Sling surgery | CFDA | 4 & 12 weeks | LPP | HE, Trichrome | None |

| 2010/Xu [63] | Pudendal nerve transection rats | Allogeneic SkMSC | Periurethral/1,000,000 | GFP | 1 & 4 weeks | LPP | FVIIIRA, Trichrome | None |

| 2011/Zhao [21] | Pudendal nerve transection rats | Autologous ADSC | Periurethral/1,000,000 | LacZ | 2, 6, & 8 weeks | LPP | PGP9.5, Trichrome | None |

| 2011/Kim [47] | Pudendal nerve transection rats | Allogeneic BMSC | Periurethral/1,500,000 | DAPI | 4 weeks | LPP | HE | SMA, Vimentin, Desmin |

| 2011/Corcos [46] | Pudendal nerve transection rats | Allogeneic BMSC | Periurethral/500,000 | PKH26 | 4 weeks | LPP | HE | Myosin, Desmin |

| 2011/Wu [20] | Pudendal nerve transection rats | Allogeneic ADSC | Periurethral/5,000,000 | Hoechst 33258 | 2 weeks | LPP | HE, Trichrome | None |

| 2011/Watanabe [22a] | Pelvic nerve transection rats | Allogeneic ADSC | Periurethral/3,000,000 | GFP | 2 & 4 weeks | LPP | HE, Trichrome | SMA, desmin |

| 2011/Sebe [30] | 12 female patients | Autologous SkMSC | Endourethral/10 to 50 million | NA | 1, 3, 6, 12 months | Clinical, Urodynamic | NA | NA |

In chronicle order based on PubMed listing. AchR, acetylcholine receptor; HE, hematoxylin eosin; LPP, leak point pressure; NA, not applicable; EM, electron microscopy; IF, immunofluorescence; FVIIIRA, factor VIII-related antigen.

Clinical Trials

The first 5 clinical studies of SC-for-SUI therapy were all published in 2007–2008 by the same group of investigators [22–26]. Two of them have now been retracted [25,26], and the reason for one of the retractions is that there were “many irregularities in the conduct of their work,” citing an Austrian government's report that concludes that “there were critical deficiencies in the way patients' consent was obtained and source data were documented” [27]. Apart from these ethical concerns, the 5 studies together reported that treatment with SkMSCs (some with co-injection of fibroblasts) resulted in cure rates of 80%–90% for both male and female patients. In another clinical trial of using SkMSCs to treat SUI, Carr et al. [28] reported improvements in 5 of 8 women, with one achieving total continence. In another clinical trial of using CBSCs to treat SUI, Lee et al. [29] reported improvements in 70%–80% of 39 female patients. A small clinical trial of using ADSCs to treat 2 male SUI patients also reported favorable outcomes, but the publication has now been retracted with no reasons given [18]. Most recently, a clinical trial using SkMSCs to treat SUI women reported that 3 of the 12 patients were dry at 12 months, 7 others showed improvements on pad test but not on voiding diary, and the remaining 2 patients were slightly worsened by the procedure. Overall, quality of life was improved in half of the patients [30].

Preclinical Trials

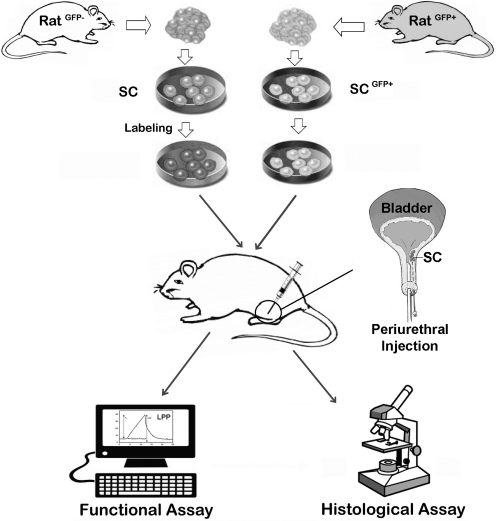

A typical preclinical trial of SC therapy for SUI is schematically depicted in Fig. 1. It involves the isolation, cultivation, sorting, and modification of SCs, followed by labeling them with a cell-tracking agent. The labeled SCs are then injected into the urethra of an SUI animal model. Weeks or months later, the animals are tested for urethral function, usually by measurement of leak point pressure (LPP). The animals are then sacrificed for histological assessment of the urethra and tracking of injected SCs.

FIG. 1.

A schematic representation of the experimental procedures of a typical preclinical stem cell therapy for stress urinary incontinence. The donor rat and recipient rat can be the same (autologous) or different (allogeneic). SCs are isolated from skeletal muscle, bone marrow, or adipose tissue, and are then modified or sorted as desired by some researchers. Labeling of SCs, which is unnecessary if from a GFP donor rat, usually incorporates a chemical agent that can be later detected by color development or fluorescence. Transplantation of the labeled SCs is most commonly done by periurethral injection, which deposits cells beneath the mucosa in the sphincter of an animal whose urethral function has been compromised by various means, for example, pudendal nerve injury or vagina distension. Weeks or months after SC transplantation, the animals are tested for urethral function, most commonly by measurement of LPP. The animals are then sacrificed for histological assessment of the urethra and identification of the injected SCs. SC, stem cell; LPP, leak point pressure; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Animal models

Rats were used in all preclinical trials except the first study, which employed mice (Table 1). Conditions mimicking SUI were usually induced by 1 of 3 alternative interventions, namely, sphincter injury, nerve injury, and vagina distension (VD). Sphincter injury can be induced by cauterization, electrocoagulation, or injection of myotoxin. Nerve injury was done by transection or crush on either the sciatic or pudendal nerves. The pudendal nerve injury rat model has been used most frequently in SC-for-SUI preclinical trials (Table 1), but it is not a durable animal model as urethral function tends to recover with increasing time at ∼2 weeks postinjury [31]. The VD model, which simulates birth trauma [32], is the most widely used animal model for mechanistic study of childbirth-induced tissue injury and recovery [31]. The VD procedure involves insertion of a Foley catheter (10 to 22 Fr) in the vagina, filling the balloon with saline (3 to 5 mL), and leaving it in place for 1–4 h with added weights (∼130 g). Four-hour VD resulted in longer-lasting urethral dysfunction than 1-h VD [33]. Variations include extra procedures such as parturition prior to VD and ovariectomy post VD that purport to better simulate birth trauma and menopause, respectively [34].

The main limitation of the VD-induced SUI model is its short durability [35,36]. Specifically, Pan et al. [33] found that, compared with sham-treated counterparts, VD-treated virgin rats exhibited significantly lower urethral resistance, as assessed by LPP test, at 10 days but not at 6 weeks after VD. More recently, Lin et al. [37] showed that, compared with sham-treated counterparts, VD-treated virgin mice displayed decreased LPP at 4 and 10 days but not at 20 days post-VD. Thus, VD alone is incapable of creating a rodent model suitable for testing SUI treatment efficacy beyond the 6-week time point. However, in one of the SC preclinical studies, VD-treated virgin rats were found to exhibit sharply lower LPP at 3 months when compared with those at 1 month after VD [19]. And, it is at the 3-month time point that in vitro myodifferentiated ADSCs were found to exhibit stronger therapeutic effects than undifferentiated ADSCs. Thus, the study's conclusion that in vitro myodifferentiation increases ADSC's therapeutic capability is based on an animal model that contradicts those designed specifically for the study of time-dependent VD-induced urethral dysfunction (see additional details in next subsection).

Stem cells

SkMDCs, which have been called variously as myoblasts, satellite cells, muscle progenitor cells (MPCs), and muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs), were used in all studies before 2008 (Table 1). However, it should be cautioned that even bearing the same name and tested by the same group of researchers, the actual cell preparations might differ considerably from one study to another. This is mainly due to uncertainty about what really constitute MDSCs and lacking of a standardized procedure to isolate and to culture these cells [38–40]. In a series of studies leading to the clinical trial by Carr et al. [28], the preparation of SkMSCs was reported to require 3 to 7 weeks in order to attain a sufficient cell number for autologous injection into human patients [41]. Such a lengthy time course is not surprising because skeletal muscle tissue can only be procured from a patient in limited quantity and the separation of SCs from non-SCs requires a week-long “preplate” procedure [42]. Therefore, a long period of time is required to select and to propagate a small number of primarily derived SkMSCs. More importantly, concerns over the loss of regenerative potential in isolated MPCs have led to the reversal from a cell-based therapy to a technically more challenging technique of skeletal muscle fiber implantation for the experimental treatment of SUI [17,43–45]. As such, in more recent years, other SC types have increasingly been used in preclinical studies (Table 1).

BMSCs have been used in 4 preclinical studies [46–49] but not in clinical studies (Table 1). One of these studies used the SCs for seeding a degradable silk scaffold, which was then implanted as a sling in SUI rats [49]. Since the cells were not used to treat the underlying tissue defect per se, this study does not fit the SC-for-SUI criterion set out in the section under “Rationale for using SC therapy.” In another study [47], BMSCs were said to be “taken from the preplate 6,” citing the preplate technique used in a previous study for the isolation of SkMSCs [42]. As such, it is not entirely certain that BMSCs were used in this study. In any case, the limited amount of tissue that can be safely harvested from a patient's bone marrow is a limiting factor going forward with BMSCs as a clinically applicable cell type.

CBSCs were tested in one preclinical and one clinical study by the same group of researchers [29,50]. Interestingly, in the preclinical study [50] human CBSCs were transplanted onto immunocompetent rats in the absence of immunosuppressant, suggesting that CBSCs can be transplanted in a xenogeneic fashion. While detailed discussion on the xenogeneic aspect of SC transplantation is beyond the scope of this article, it should be noted that numerous studies have demonstrated the feasibility of xenotransplantation with various types of MSCs, including BMSCs and ADSCs. In regard to ADSCs, we have unpublished data showing the efficacy of its xenotransplantation for SUI treatment. In regard to published studies, ADSCs have been tested in 1 clinical and 4 preclinical studies (Table 1), with the clinical study having been retracted. Due to its abundant tissue source and the availability of automated isolation [51], ADSC is the only SC type that can be isolated and transplanted autologously on a same-day basis [52].

Some studies have tested modified or sorted SCs prior to their transplantation. For example, SkMSCs were sorted into CD34+CD45− and CD34−CD45− populations; however, whether one population is better than the other remains unknown because no comparison data were provided [53]. In another study ADSCs were treated with 5-azacytidine for possible differentiation into myoblasts prior to their transplantation into a VD-treated SUI rat model [19]. Although expression of desmin and myosin was identified in cultured cells, whether the transplanted cells express muscle-specific markers remains unknown because no histological data were provided. Furthermore, although LPP test showed that myodifferentiated ADSCs were better than undifferentiated ADSCs at 3 months after transplantation, such data are perplexing because VD-treated virgin rats are known to regain normal urethral resistance in 6 weeks [31,33] and thus assessment of SC treatment efficacy at 3 months post-VD cannot be expected to yield valid differences (see other details in previous subsection). So, whether SC modification provides any beneficial effects remains unknown, although it is obvious that any modifications inevitably introduce undesirable or risk factors such as contamination, prolonged cell culturing, reduced cell number, and so on.

Cell labeling

A wide variety of methods have been used to monitor the distribution and survival of transplanted SCs. In SC-SUI field, 2 studies by the same group of researchers transplanted human SkMSCs to rats; therefore, cell tracking was done by immunofluorescent detection of human-specific lamins [54,55]. Another study labeled BMSCs with fluorescent dye CFDA for the purpose of visualizing cell seeding on scaffold, not for cell tracking [49]; therefore, the use of this dye will not be discussed further. All other SC-SUI studies either did not report cell tracking or tracked transplanted SCs that were labeled with LacZ, GFP, DiI, PKH-26, BrdU, EdU, or Hoechst 33258. Except for Hoechst 33258, all of these labels have been discussed in our recent review on SC therapy for erectile dysfunction (ED) [56]. Specifically, we cautioned that, due to problems inherently associated with most of these labels (eg, cytotoxicity, adsorption by host cells, and host issue background), their use for cell tracking might have led to erroneous data interpretation. These problems have also occurred in SC-SUI studies but will not be reiterated further. Hoechst 33258, which was not discussed in the SC-ED review because of its absence in SC-ED studies, will be discussed briefly below, as it was used in a recent SC-SUI study [20].

Hoechst dyes are a family of bis-benzimides that are cell membrane permeable and bind to DNA noncovalently in the minor groove of AT-rich sequences. In a study designed to examine possible transfer of label from transplanted cells to host cells, Iwashita et al. [57] found evidence of label transfer within hours of cell transplantation, and the label persisted in the host cells for at least 4 weeks posttransplantation. In another study designed to examine possible label transfer in cultured cells, Mohorko et al. [58] found that >50% of the initially unlabeled cells became labeled within 6 h of co-culturing with labeled cells. The authors thus concluded that Hoechst dyes are unsuitable marker for cell transplantation research. These studies and another, in which DAPI was found to get transferred from labeled transplantation cells to unlabeled host cells [59], point out that all noncovalent DNA-binding dyes should be avoided when it comes to selecting labels for tracking SCs in transplantation studies. Instead, covalent DNA-binding labels such as BrdU and EdU are safer choices, and due to its more efficient detection procedure and more reliable histological outcome, EdU is recommended over BrdU [60,61].

Cell injection routes

Transplantation of SCs for the treatment of SUI has been done almost exclusively by intraurethral injection. In experimental animals this injection was done exclusively via the periurethral route while the transurethral route was used far more often in human patients (Table 1). The clinical trial by Carr et al. [28] is the only study that utilized both injection routes and the results indicate that both routes produced positive outcomes. Regardless of the injection route, the goal of intraurethral injection is to deposit the cells in the submucosa of the urethral sphincter, thereby allowing the injected cells to differentiate into muscle cells and/or to encourage the regeneration of host tissues. The preclinical trial by Lin et al. [14] is the only study that utilized a nonurethral injection route. Specifically, the study performed both periurethral and intravenous (IV) injections, and the results indicate similar beneficial outcomes. In addition, homing factor SDF-1 was identified in the urethra of VD-treated rats, suggesting its role in guiding the IV-injected SCs to the injured urethra. Similarly, in a recent study, which did not assess treatment efficacy, IV-injected BMSCs were found to home into the urethra, vagina, rectum, and levator ani muscle at significantly higher rates in VD-treated than in sham-treated rats [62]. Thus, IV-injected SCs have the potential to simultaneously help the repair/regeneration of all damaged tissues. However, VD-induced injury is acute, whereas most clinical SUI is chronic; as such, whether the IV route of SC injection is clinically applicable requires further investigation.

Functional assessment

In clinical trials, functional assessment was done largely according to established clinical procedures such as measurements of pad weights, bladder diaries, and quality of life. Urodynamics such as maximal urinary flow rate, residual urine, maximal urethral closing pressure, and electromyography were also assessed in a few clinical trials.

In preclinical trials the most frequently used parameter to assess functional recovery is LPP, and this has been measured predominantly by either the Crede or the vertical tilt table method. The Crede technique, employed in 6 SC-SUI studies [19–21,46,49,63], is performed manually on an anesthetized animal by applying an increasing external force on the abdomen over the bladder with the experimenter's index finger. Immediately after a leak is visually observed at the urethral meatus, the experimenter lifts his/her finger off, and the peak intravesical pressure, that is, the LPP, is recorded via an intravesical catheter. A variation of this technique involves the use of a Q-tip for applying pressure directly on the bladder, and in our experience, this produces more consistent data than the finger-on-the-abdomen alternative. In the vertical tilt table method, which was employed in 8 SC-SUI studies [42,47,50,54,55,64–66], an anesthetized animal is mounted on a table so as to mimic human's upright posture. Increases in intravesical pressure are accomplished by incrementally raising the height of a saline reservoir, which is connected to the bladder via an intravesical catheter and a pressure transducer. The pressure at which a leak is visually observed at the urethral meatus is recorded as the LPP.

Two studies by the same group of researchers have performed electrical stimulation of the urethral sphincteric neurovascular bundle [44,45]. These authors considered that such a test permitted an indirect but dynamic and selective measurement of sphincter contraction, as opposed to the measurement of passive urethral resistance by the above-mentioned LPP test. In spite of these differences, nearly all studies reported improved urethral function after SC transplantation.

Histological assessment

With the exception of Fu et al. [19], all preclinical studies have performed histological examination of the urethra to (i) locate transplanted SCs, (ii) identify possible SC differentiation, and/or (iii) assess tissue improvement. In regard to localization of transplanted cells, most studies reported the detection of few or absence of such cells. One possible explanation is that the histological assessment was often performed several weeks after the initial cell transplantation; thus, most of these cells might have reached the end of their natural lifespan. In regard to tissue assessment, which was most frequently done by HE or trichrome staining, improvement in the musculature was observed in nearly all preclinical studies.

In regard to the identification of possible differentiation of the transplanted SCs, it is somewhat surprising that only 5 studies have reported having made such attempts. By using immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopy, Hoshi et al. [53] reported that transplanted SkMSCs differentiated into skeletal muscle fibers, Schwann cells, endothelial cells, and pericytes. Moreover, the skeletal muscle fibers were innervated as evidenced by the presence of neuromuscular junctions, and the endothelial cells and pericytes were localized in blood vessels around the urethra. Similarly, although on a much smaller scale, Kinebuchi et al. [48] reported that transplanted BMSCs differentiated into striated muscle cells and peripheral nerve cells. In regard to the impressive findings by Hoshi et al. [53], it should be noted that in a more recent study [67] the same group of researchers made similar observations regarding the multilineage differentiation of transplanted SkMSCs in a neurogenic bladder dysfunction rat model. However, as mentioned in the “Stem cells” subsection, there was evidence that muscle-derived cells had limited differentiation potential and this had led to the reversal from a muscle cell–based therapy to a muscle fiber implantation approach. As such, the extraordinary differentiation capability of SkMSCs demonstrated in the studies by Kinebuchi et al. and by Nitta et al. remains seemingly improbable. In any case, the remaining 3 SC-for-SUI studies are more on the negative side about SC's differentiation after their intraurethral transplantation. Specifically, Lim et al. [50] did not find differentiation of transplanted CBSCs, Lin et al. [14] found that few transplanted ADSCs expressed α-smooth muscle actin, and Kim et al. [47] only speculated about possible differentiation of transplanted BMSCs.

Future Directions

SUI is one of the few diseases that have been treated with SCs in clinical trials. However, due to ethical and regulatory concerns some of the published studies have since been retracted. As such, overcoming these concerns is perhaps the most important issue going forward for future SC-for-SUI clinical trials. Another issue for future clinical trials is the choice of SC type. As shown in Table 1 and discussed under “Clinical Trials,” the great majority of past clinical trials tested the therapeutic efficacy of SkMSCs. But, this particular SC type requires a lengthy isolation/propagation process and therefore is not the optimal SC type for clinical application. In contrast, ADSC is a SC type that can be isolated from and transplanted back to the patient on the same day. Furthermore, devices for automated isolation of ADSCs are commercially available, for example, the Celution System by Cytori, Inc. (San Diego, CA) [51], the Cell Isolation System by Tissue Genesis, Inc. (Honolulu, HI), and the YC-100 Stem Cell Isolator by Medikan Co. (Pusan, South Korea). Thus, in terms of cost, risk, ethics, expediency, and effectiveness, ADSCs should compete favorably.

Since we have demonstrated that IV injection produced similarly therapeutic effects as intraurethral injection [14], this route of SC administration should be further explored in future studies due to its ease of application. Indeed, a recent study has found that IV-injected BMSCs homed into injured tissues in a VD-induced SUI rat model [62], and another recent study demonstrated that IV injection of ADSCs produced no adverse side effects in humans or mice [68]. Thus, the opportune time appears to have arrived for a clinical trial with IV injection of SCs, particularly ADSCs, for the treatment of SUI.

While SC-for-SUI clinical trials have produced favorable outcomes, there remain many issues that can only be resolved by animal testing. However, SUI animal models that have been utilized in published SC-for-SUI studies lack a critical clinical component, namely, the chronic nature of SUI. Specifically, while most SUI patients incurred parturition-related urethral injuries years or decades ago, SUI animal models usually regain urinary continence within weeks. In addition, in most published studies SCs were transplanted soon after the urethral injury; thus, the intervention is preventive in nature, not truly therapeutical. As such, to be more clinically relevant, future preclinical studies should use a chronic type of SUI animal model and conduct SC transplantation several days or even weeks after the initial insult. In regard to the creation of chronic SUI models, Pauwels et al. [35] have described a repeated VD method and a surgical urethral transposition method. In addition, we have recently shown that intraperitoneal injection of beta-aminopropionitrile (BAPN) in VD-treated rats exacerbated the urethral dysfunction and tissue damage [69]. This additional treatment with BAPN thus has the potential to increase the durability of both the VD and nerve injury SUI rat models.

One of the most pressing issues in SC research is the lack of a clear understanding of how SCs exert their therapeutic effects. Although SC therapy was conceived on the premise that SCs could differentiate into various cell types and thereby replenish damaged/dysfunctional cells, in recent years it is becoming increasingly clear that cellular differentiation alone is far from adequate to accomplish such goals. For example, in a recent review article Mazo et al. [70] estimated that up to 1 trillion SCs are needed for replacing the damaged cardiomyocytes in a cardiac failure patient. Even if we assume 100% cardiomyocyte differentiation, up to 2 billion SCs are still needed for transplantation into an experimental rat host—a figure that is 1,000 times higher than what has been used in most published studies. Thus, the chance of a successful cell differentiation–based therapy—even in the preclinical stage—is remote. On the other hand, the paracrine aspect as a mechanism for SC's therapeutic effects is gaining broader acceptance [71]. The remaining challenges for future studies are finding what paracrine factors and knowing how they exert therapeutic effects. While a detailed discussion on these issues is beyond the scope of this review, suffice it to say that available evidence points to the following factors: (i) angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF and bFGF play key roles in overall tissue regeneration, (ii) neurotrophins such as NGF appear to promote axonal regeneration, (iii) homing factors such as SDF-1 can mobilize the host's own stem/repair cells to injury sites, and (iv) certain interleukins might modulate inflammatory response [72,73].

In summary, future studies should focus on (i) adhering to regulatory guidelines for clinical trials; (ii) selecting the most clinically applicable SC type; (iii) creating a long-term, clinically relevant SUI animal model; (iv) testing the feasibility of IV SC injection; and (v) improving our understanding of SC's therapeutic mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK64538 and DK069655).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Norton P. Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women. Lancet. 2006;367:57–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy R. Muller N. Urinary incontinence: economic burden and new choices in pharmaceutical treatment. Adv Ther. 2006;23:556–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02850045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbs CF. Johnson TM., 2nd Ouslander JG. Office management of geriatric urinary incontinence. Am J Med. 2007;120:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dooley Y. Kenton K. Cao G. Luke A. Durazo-Arvizu R. Kramer H. Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence prevalence: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol. 2008;179:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shamliyan TA. Kane RL. Wyman J. Wilt TJ. Systematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:459–473. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr LA. Bulking agents in the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: history, outcomes, patient populations, and reimbursement profile. Rev Urol. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S3–S11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sweat SD. Lightner DJ. Complications of sterile abscess formation and pulmonary embolism following periurethral bulking agents. J Urol. 1999;161:93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilchrist AS. Rovner ES. Managing complications of slings. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:291–296. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283476eb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delancey JO. Why do women have stress urinary incontinence? Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(Suppl 1):S13–17. doi: 10.1002/nau.20888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan DM. Umek W. Guire K. Morgan HK. Garabrant A. DeLancey JO. Urethral sphincter morphology and function with and without stress incontinence. J Urol. 2009;182:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin CS. Advances in stem cell therapy for the lower urinary tract. World J Stem Cells. 2010;2:1–4. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v2.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin CS. Stem cell therapy for the bladder—where do we stand? J Urol. 2011;185:779–780. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin CS. Lue TF. Stem cells in urology: how far have we come? Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5:521. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin G. Wang G. Banie L. Ning H. Shindel AW. Fandel TM. Lue TF. Lin CS. Treatment of stress urinary incontinence with adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:88–95. doi: 10.3109/14653240903350265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colazzo F. Sarathchandra P. Smolenski RT. Chester AH. Tseng YT. Czernuszka JT. Yacoub MH. Taylor PM. Extracellular matrix production by adipose-derived stem cells: implications for heart valve tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chancellor MB. Yokoyama T. Tirney S. Mattes CE. Ozawa H. Yoshimura N. de Groat WC. Huard J. Preliminary results of myoblast injection into the urethra and bladder wall: a possible method for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence and impaired detrusor contractility. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:279–287. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:3<279::aid-nau9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yiou R. Dreyfus P. Chopin DK. Abbou CC. Lefaucheur JP. Muscle precursor cell autografting in a murine model of urethral sphincter injury. BJU Int. 2002;89:298–302. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T. Gotoh M. Hattori R. Toriyama K. Kamei Y. Iwaguro H. Matsukawa Y. Funahashi Y. Periurethral injection of autologous adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy: report of two initial cases. Int J Urol. 2010;17:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu Q. Song XF. Liao GL. Deng CL. Cui L. Myoblasts differentiated from adipose-derived stem cells to treat stress urinary incontinence. Urology. 2010;75:718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu G. Song Y. Zheng X. Jiang Z. Adipose-derived stromal cell transplantation for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Tissue Cell. 2011;43:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao W. Zhang C. Jin C. Zhang Z. Kong D. Xu W. Xiu Y. Periurethral injection of autologous adipose-derived stem cells with controlled-release nerve growth factor for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence in a rat model. Eur Urol. 2011;59:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitterberger M. Marksteiner R. Margreiter E. Pinggera GM. Colleselli D. Frauscher F. Ulmer H. Fussenegger M. Bartsch G. Strasser H. Autologous myoblasts and fibroblasts for female stress incontinence: a 1-year follow-up in 123 patients. BJU Int. 2007;100:1081–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitterberger M. Marksteiner R. Margreiter E. Pinggera GM. Frauscher F. Ulmer H. Fussenegger M. Bartsch G. Strasser H. Myoblast and fibroblast therapy for post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: 1-year followup of 63 patients. J Urol. 2008;179:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitterberger M. Pinggera GM. Marksteiner R. Margreiter E. Fussenegger M. Frauscher F. Ulmer H. Hering S. Bartsch G. Strasser H. Adult stem cell therapy of female stress urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2008;53:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strasser H. Marksteiner R. Margreiter E. Mitterberger M. Pinggera GM. Frauscher F. Fussenegger M. Kofler K. Bartsch G. Transurethral ultrasonography-guided injection of adult autologous stem cells versus transurethral endoscopic injection of collagen in treatment of urinary incontinence. World J Urol. 2007;25:385–392. doi: 10.1007/s00345-007-0190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strasser H. Marksteiner R. Margreiter E. Pinggera GM. Mitterberger M. Frauscher F. Ulmer H. Fussenegger M. Kofler K. Bartsch G. Autologous myoblasts and fibroblasts versus collagen for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2179–2186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinert S. Horton R. Retraction—autologous myoblasts and fibroblasts versus collagen [corrected] for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: a [corrected] randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:789–790. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carr LK. Steele D. Steele S. Wagner D. Pruchnic R. Jankowski R. Erickson J. Huard J. Chancellor MB. 1-year follow-up of autologous muscle-derived stem cell injection pilot study to treat stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:881–883. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0553-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CN. Jang JB. Kim JY. Koh C. Baek JY. Lee KJ. Human cord blood stem cell therapy for treatment of stress urinary incontinence. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:813–816. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.6.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebe P. Doucet C. Cornu JN. Ciofu C. Costa P. de Medina SG. Pinset C. Haab F. Intrasphincteric injections of autologous muscular cells in women with refractory stress urinary incontinence: a prospective study. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:183–189. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang HH. Damaser MS. Animal models of stress urinary incontinence. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2011:45–67. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-16499-6_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin AS. Carrier S. Morgan DM. Lue TF. Effect of simulated birth trauma on the urinary continence mechanism in the rat. Urology. 1998;52:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan HQ. Kerns JM. Lin DL. Liu S. Esparza N. Damaser MS. Increased duration of simulated childbirth injuries results in increased time to recovery. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1738–R1744. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00784.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sievert KD. Emre Bakircioglu M. Tsai T. Dahms SE. Nunes L. Lue TF. The effect of simulated birth trauma and/or ovariectomy on rodent continence mechanism. Part I: functional and structural change. J Urol. 2001;166:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauwels E. De Wachter S. Wyndaele JJ. Evaluation of different techniques to create chronic urinary incontinence in the rat. BJU Int. 2009;103:782–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08158.x. discussion 785–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez LV. Chen S. Jack GS. de Almeida F. Lee KW. Zhang R. New objective measures to quantify stress urinary incontinence in a novel durable animal model of intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1332–R1338. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00760.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin YH. Liu G. Li M. Xiao N. Daneshgari F. Recovery of continence function following simulated birth trauma involves repair of muscle and nerves in the urethra in the female mouse. Eur Urol. 2010;57:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson WM. Nesti LJ. Tuan RS. Potential therapeutic applications of muscle-derived mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:505–517. doi: 10.1517/14712591003610606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu SH. Wei CF. Yang AH. Chancellor MB. Wang LS. Chen KK. Isolation and characterization of human muscle-derived cells. Urology. 2009;74:440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu X. Wang S. Chen B. An X. Muscle-derived stem cells: isolation, characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;340:549–567. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0978-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furuta A. Carr LK. Yoshimura N. Chancellor MB. Advances in the understanding of sress urinary incontinence and the promise of stem-cell therapy. Rev Urol. 2007;9:106–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee JY. Cannon TW. Pruchnic R. Fraser MO. Huard J. Chancellor MB. The effects of periurethral muscle-derived stem cell injection on leak point pressure in a rat model of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s00192-002-1004-5. discussion 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lecoeur C. Swieb S. Zini L. Riviere C. Combrisson H. Gherardi R. Abbou C. Yiou R. Intraurethral transfer of satellite cells by myofiber implants results in the formation of innervated myotubes exerting tonic contractions. J Urol. 2007;178:332–337. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yiou R. Yoo JJ. Atala A. Restoration of functional motor units in a rat model of sphincter injury by muscle precursor cell autografts. Transplantation. 2003;76:1053–1060. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000090396.71097.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yiou R. Yoo JJ. Atala A. Failure of differentiation into mature myotubes by muscle precursor cells with the side-population phenotype after injection into irreversibly damaged striated urethral sphincter. Transplantation. 2005;80:131–133. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000158276.36005.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corcos J. Loutochin O. Campeau L. Eliopoulos N. Bouchentouf M. Blok B. Galipeau J. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for external urethral sphincter restoration in a rat model of stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:447–455. doi: 10.1002/nau.20998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim SO. Na HS. Kwon D. Joo SY. Kim HS. Ahn Y. Bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation enhances closing pressure and leak point pressure in a female urinary incontinence rat model. Urol Int. 2011;86:110–116. doi: 10.1159/000317322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kinebuchi Y. Aizawa N. Imamura T. Ishizuka O. Igawa Y. Nishizawa O. Autologous bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation into injured rat urethral sphincter. Int J Urol. 2010;17:359–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou XH. Zhi YL. Chen X. Jin HM. Wang LL. Jiang YZ. Yin Z. Ouyang HW. Mesenchymal stem cell seeded knitted silk sling for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4872–4879. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim JJ. Jang JB. Kim JY. Moon SH. Lee CN. Lee KJ. Human umbilical cord blood mononuclear cell transplantation in rats with intrinsic sphincter deficiency. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:663–670. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.5.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin K. Matsubara Y. Masuda Y. Togashi K. Ohno T. Tamura T. Toyoshima Y. Sugimachi K. Toyoda M. Marc H. Douglas A. Characterization of adipose tissue-derived cells isolated with the Celution system. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:417–426. doi: 10.1080/14653240801982979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshimura K. Sato K. Aoi N. Kurita M. Hirohi T. Harii K. Cell-assisted lipotransfer for cosmetic breast augmentation: supportive use of adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:48–55. doi: 10.1007/s00266-007-9019-4. discussion 56–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoshi A. Tamaki T. Tono K. Okada Y. Akatsuka A. Usui Y. Terachi T. Reconstruction of radical prostatectomy-induced urethral damage using skeletal muscle-derived multipotent stem cells. Transplantation. 2008;85:1617–1624. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318170572b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furuta A. Jankowski RJ. Pruchnic R. Egawa S. Yoshimura N. Chancellor MB. Physiological effects of human muscle-derived stem cell implantation on urethral smooth muscle function. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:1229–1234. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0608-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim YT. Kim DK. Jankowski RJ. Pruchnic R. Usiene I. de Miguel F. Chancellor MB. Human muscle-derived cell injection in a rat model of stress urinary incontinence. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:391–393. doi: 10.1002/mus.20827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin CS. Xin ZC. Wang Z. Deng C. Huang YC. Lin G. Lue TF. Stem cell therapy for erectile dysfunction: a critical review. Stem Cells Dev. 2011 doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0303. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iwashita Y. Crang AJ. Blakemore WF. Redistribution of bisbenzimide Hoechst 33342 from transplanted cells to host cells. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1013–1016. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004070-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohorko N. Kregar-Velikonja N. Repovs G. Gorensek M. Bresjanac M. An in vitro study of Hoechst 33342 redistribution and its effects on cell viability. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:573–580. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht570oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castanheira P. Torquetti LT. Magalhas DR. Nehemy MB. Goes AM. DAPI diffusion after intravitreal injection of mesenchymal stem cells in the injured retina of rats. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:423–431. doi: 10.3727/096368909788809811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin G. Huang YC. Shindel AW. Banie L. Wang G. Lue TF. Lin CS. Labelling and tracking of mesenchymal stromal cells with EdU. Cytotherapy. 2009;11:864–873. doi: 10.3109/14653240903180084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Salic A. Mitchison TJ. A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2415–2420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cruz M. Dissaranan C. Cotleur A. Kiedrowski M. Penn M. Damaser M. Pelvic organ distribution of mesenchymal stem cells injected intravenously after simulated childbirth injury in female rats. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/612946. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu Y. Song YF. Lin ZX. Transplantation of muscle-derived stem cells plus biodegradable fibrin glue restores the urethral sphincter in a pudendal nerve-transected rat model. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43:1076–1083. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2010007500112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chermansky CJ. Tarin T. Kwon DD. Jankowski RJ. Cannon TW. de Groat WC. Huard J. Chancellor MB. Intraurethral muscle-derived cell injections increase leak point pressure in a rat model of intrinsic sphincter deficiency. Urology. 2004;63:780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kwon D. Kim Y. Pruchnic R. Jankowski R. Usiene I. de Miguel F. Huard J. Chancellor MB. Periurethral cellular injection: comparison of muscle-derived progenitor cells and fibroblasts with regard to efficacy and tissue contractility in an animal model of stress urinary incontinence. Urology. 2006;68:449–454. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee JY. Paik SY. Yuk SH. Lee JH. Ghil SH. Lee SS. Long term effects of muscle-derived stem cells on leak point pressure and closing pressure in rats with transected pudendal nerves. Mol Cells. 2004;18:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nitta M. Tamaki T. Tono K. Okada Y. Masuda M. Akatsuka A. Hoshi A. Usui Y. Terachi T. Reconstitution of experimental neurogenic bladder dysfunction using skeletal muscle-derived multipotent stem cells. Transplantation. 2010;89:1043–1049. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181d45a7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ra JC. Shin IS. Kim SH. Kang SK. Kang BC. Lee HY. Kim YJ. Jo JY. Yoon EJ. Choi HJ. Kwon E. Safety of intravenous infusion of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in animals and humans. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1297–1308. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang G. Lin G. Zhang H. Qiu X. Ning H. Banie L. Fandel T. Albersen M. Lue TF. Lin CS. Effects of prolonged vaginal distension and beta-aminopropionitrile on urinary continence and urethral structure. Urology. 2011;78:968. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.07.1381. e913-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mazo M. Gavira JJ. Pelacho B. Prosper F. Adipose-derived stem cells for myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011;4:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9246-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin CS. Lue TF. Adipose-derived stem cells for urological diseases: therapy through paracrine actions. In: Hayat MA, editor. Stem Cells and Cancer Stem Cells. Vol. 4. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Baraniak PR. McDevitt TC. Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen Med. 2010;5:121–143. doi: 10.2217/rme.09.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furuta A. Jankowski RJ. Honda M. Pruchnic R. Yoshimura N. Chancellor MB. State of the art of where we are at using stem cells for stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:966–971. doi: 10.1002/nau.20448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cannon TW. Lee JY. Somogyi G. Pruchnic R. Smith CP. Huard J. Chancellor MB. Improved sphincter contractility after allogenic muscle-derived progenitor cell injection into the denervated rat urethra. Urology. 2003;62:958–963. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]