Abstract

Background

In Western countries, a history of major depression (MD) is associated with reports of received parenting that is low in warmth and caring and high in control and authoritarianism. Does a similar pattern exist in women in China?

Method

Received parenting was assessed by a shortened version of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in two groups of Han Chinese women: 1970 clinically ascertained cases with recurrent MD and 2597 matched controls. MD was assessed at personal interview.

Results

Factor analysis of the PBI revealed three factors for both mothers and fathers: warmth, protectiveness, and authoritarianism. Lower warmth and protectiveness and higher authoritarianism from both mother and father were significantly associated with risk for recurrent MD. Parental warmth was positively correlated with parental protectiveness and negatively correlated with parental authoritarianism. When examined together, paternal warmth was more strongly associated with lowered risk for MD than maternal warmth. Furthermore, paternal protectiveness was negatively and maternal protectiveness positively associated with risk for MD.

Conclusions

Although the structure of received parenting is very similar in China and Western countries, the association with MD is not. High parental protectiveness is generally pathogenic in Western countries but protective in China, especially when received from the father. Our results suggest that cultural factors impact on patterns of parenting and their association with MD.

Keywords: Major depression, parent–child relations, psychometrics, risk factors, social behaviour

Introduction

A substantial body of literature suggests a relationship between the quality of parenting received as a child and risk for psychiatric illness in general and for major depression (MD) in particular (Parker, 1979, 1983; Burbach & Borduin, 1986; Perris et al. 1986, 1994; Gerlsma et al. 1990; Duggan et al. 1998; Kendler et al. 2000). However, almost all of the available studies have been conducted in Western countries. Little is known of the impact of received parenting on the risk for MD in China.

We are aware of three studies that have examined the association between experienced parenting and depression in China, only one of which assessed the syndrome of MD. Chen (1991) examined 1441 Taiwanese college students and reported that the vulnerability to MD increased when family members failed to provide adequate support, when mothers did not provide consistent love or when fathers were too critical. Kao et al. (1998) explored the relationship between parenting and current symptomatology in 1434 adolescent students in Taiwan: strict parenting, characterized by high levels of control, was correlated with depressive symptoms. Finally, Liu (2003) examined 454 children from Eastern Taiwan. The Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker et al. 1979) was used to assess received parenting. The author failed to replicate the original two-factor structure proposed by Parker et al. (1979) and instead proposed a four-factor solution, with factors termed ‘caring’, ‘indifference’, ‘autonomy’ and ‘overprotection’. Lower levels of parental care and higher levels of parental indifference were associated with elevated self-report depressive symptoms.

Our aim was to investigate ways in which received parenting impacts on the liability to MD in mainland China. To do so, we used a cohort of 1970 Chinese women diagnosed with recurrent MD. We first explored whether the dimensions of parenting in China, as revealed through the factor structure of the PBI, resemble those found in Western countries. Second, we sought to clarify how these parenting dimensions, taken one at a time and separately in mothers and fathers, impacted on risk for MD. Third, we examined how these individual parenting dimensions altered risk for MD when viewed together with the other parenting dimensions within the same parent or the same parenting factor across spouses. Fourth, we were interested in determining whether the relationship between these factors, taken singly and in combination, and risk for MD was similar in our Chinese sample to that seen previously in European and US populations.

Method

Study subjects

The data for the present study were drawn from the ongoing China, Oxford and VCU Experimental Research on Genetic Epidemiology (CONVERGE) study of MD. CONVERGE studies only women because of evidence that the genetic risk factors for MD are not entirely the same in men and women (Kendler et al. 2006). Furthermore, because of evidence that recurrence is the best index of a high familial/genetic loading for MD (Sullivan et al. 2000), cases were required to have a history of at least two MD episodes.

The results presented here are based on a total of 1970 cases recruited from 51 provincial mental health centers and psychiatric departments of general medical hospitals in 40 cities in 21 provinces, and 2597 controls recruited from patients undergoing minor surgical procedures at general hospitals or from local community centers. All cases and controls were female and had four Han Chinese grandparents. Cases and controls were matched in each collecting center. Participants provided their Chinese national identity (ID) number, which we used to assign origin to each subject. The ID number reflects the place a participant first applied for an ID card, normally the same as their household registration (‘Hu Kou’) and the place where they grew up. The majority (68.1%) of our sample lived in cities, and there was no significant difference in rates of urban versus rural residence between cases and controls (67.9% of cases had an urban address and 68.3% of controls).

Cases and controls were excluded if they had a pre-existing history of bipolar disorder, any type of psychosis or mental retardation. Cases were aged between 30 and 60 years, had had at least two episodes of MD, with the first episode occurring between age 14 and 50 years, and had not abused drug or alcohol before the first episode of MD. Controls were chosen to match the region of origin of cases, were aged between 40 and 60 years, had never experienced an episode of MD and were not blood relatives of cases. An older minimal age of controls was used to reduce the chances that they might have a subsequent first onset of MD. The mean age (and standard deviation) of cases and controls in the dataset was 45.1 (8.8) and 47.7 (5.5) years respectively.

All subjects were interviewed using a computerized assessment system that lasted on average 2 h for a case and 1 h for a control. All interviewers were psychiatrists or psychiatric nurses and were trained by the CONVERGE team for a minimum of 1 week in the use of the interview. The interview included assessment of psychopathology, demographic and personal characteristics, and psychosocial functioning. Interviews were tape-recorded and a proportion were listened to by the trained editors who provided feedback on the quality of the interviews.

The study protocol was approved centrally by the Ethical Review Board of Oxford University and the ethics committees in participating hospitals in China.

Measures

The diagnoses of lifetime MD was established with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview [CIDI; World Health Organization (WHO) lifetime version 2.1; Chinese version], which classifies diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994). The interview was originally translated into Mandarin by a team of psychiatrists in Shanghai Mental Health Center, with the translation reviewed and modified by members of the CONVERGE team.

Parent–child relationships were measured with the 16-item Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) modified by Kendler (1996) based on the original 25-item instrument described by Parker et al. (1979) . Parker (1981) has shown that depressive state does not influence scores on the PBI. All of the seven original care items from the PBI are included in the 16-item version (items 1, 4, 5, 11, 12, 17 and 18 as originally numbered) in addition to nine items from the original overprotection scale (items 7, 8, 9, 13, 15, 19, 21, 23 and 25). Information on postnatal depression was assessed using an adaptation of the Edinburgh Scale (Cox et al. 1987).

Education was treated in two ways: as the number of years of completed full-time education and as an ordinal variable divided into seven levels: no education or pre-school (scored 0), primary school or below (scored 1), junior middle school (scored 2), senior middle school or Technical and vocational school (in China, they both take the same time to be finished) (scored 3), adult/radio/television schooling, evening education or junior college (scored 4), bachelor degree (scored 5), master degree or above (scored 6). Social class was coded as one of five: (i) executive, business owner or professional; (ii) administrative personnel, clerical or sales worker; (iii) skilled manual employee; (iv) semi-skilled or unskilled; (v) other.

Both the case and control interviews were fully computerized into a bilingual system of Mandarin and English developed in-house in Oxford, and called SysQ. Skip patterns were built into SysQ. Interviews were administered by trained interviewers and entered offline in real time onto SysQ, which was installed on laptops. Once an interview was completed, a backup file containing all the previously entered interview data could be generated with database compatible format. The backup file, together with an audio recording of the entire interview, was uploaded to a designated server currently maintained in Beijing by a service provider. All the uploaded files in the Beijing server were then transferred to an Oxford server quarterly.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the statistical programming language R (R Development Core Team, 2004). Before analysis, PBI scores from six items were reversed for consistency with Parker's original scoring (Parker et al. 1979). These items are 2, 4, 10, 12, 14 and 16. A scree plot of a principal components analysis of the PBI was used to identify factors for subsequent analysis. For three dimensions, we picked high loading items and summed their responses. All parenting dimensions were centered around their means for ease of interpretation. Logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between MD and PBI dimensions. Odds ratios (ORs) were obtained by exponentializing the logistic regression coefficients.

Results

Issues in data collection

Many interviewers reported difficulties in obtaining answers to the PBI from selected respondents. Missingness for the PBI data (402/4165 subjects=9.7%) was substantially higher than that observed with other variables in our project. It was not related to general problems of comprehension as missingness was modestly, but significantly, positively associated with educational status (p=0.00006) [OR 1.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.06–1.19]. Typically, respondents did not so much refuse to report on their parenting experiences as state that the questions did not ‘make sense’ in the context of their childhood experiences. Anecdotes from individual interviewers suggested that, in some of these cases, their inability to be able to respond to the PBI items resulted from childhood experiences of substantial deprivation (where parental concerns may have been more focused on basic needs such as providing food than on the emotional aspects of parents assessed by the PBI, in addition to instances of parental abuse and neglect).

Although our interview did not assess such deprivation directly, the finding that missing data on the PBI scales was strongly associated with our two measures of childhood adversities supports the plausibility of this explanation. Among those reporting childhood neglect, 25.3% had missing PBI data versus 7.2% of those without neglect (χ2=25.5, df=1, p=0.0000004). Among those reporting childhood physical abuse, 24.8% had missing PBI data versus 7.8% of those without neglect (χ2=12.8, df=1, p=0.0003). Finally, significantly more cases failed to answer the PBI than controls (13% v. 5% respectively; χ2=108.0, df=1, p value <2.2×10−16).

Factor analysis

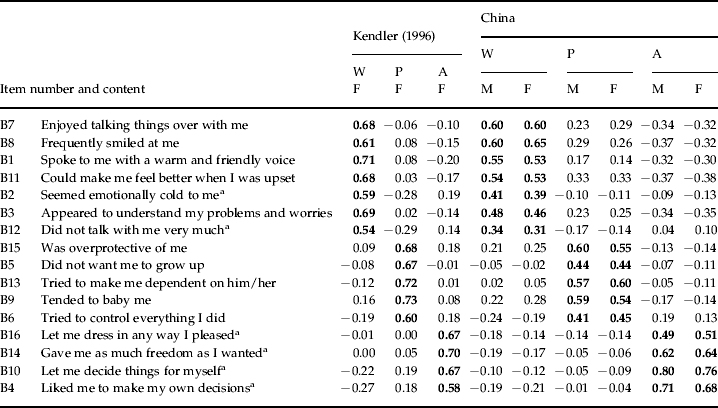

We examined the factor structure of the 16-item PBI, analyzing scores for fathers and mothers separately. In both parents, the scree plot suggested three factors that together explained 39% and 40% of the variance in mothers and fathers respectively. Table 1 shows the loadings on each item and also provides, for comparison, the results for fathers from the prior US sample of Kendler et al. (1997) . Factor loadings were reassuringly similar across the two samples. Therefore, we applied the same names to the factors in our sample: Warmth, Protectiveness and Authoritarianism. As suggested by the items, high Warmth scores reflect a caring and loving parenting style, high Protectiveness scores index an overprotective and controlling parental style, and high Authoritarianism scores reflect parenting that discourages a child's sense of independence and autonomy.

Table 1.

Factor loadings for the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) in China compared to a US study

W, Warmth; P, Protectiveness; A, Authoritarianism; F, females (mothers of subjects); M, males (fathers of subjects).

Numbers in bold in each column represent the loadings used to define the three factors (W, P and A).

Loading is reversed on these items for ease of comparability. ‘Item number’ is Parker's original numbering.

Maternal versus paternal parenting

Mothers and fathers differed in their Warmth, Protectiveness and Authoritarianism scores. Fathers were significantly more authoritarian [fathers' mean: 8.3, mothers' mean: 8.2 (t=2.40, df=4089, p=0.01)], less protective [fathers' mean: 8.7; mothers' mean: 9.1 (t=10.20, df=4088, p<0.00001)] and less warm than mothers [fathers' mean: 21.0, mothers' mean: 21.8 (t=11.99, df=4088, p<0.0001)].

Association of parenting with demographic data

We investigated whether any of the demographic features we had collected on our population were related to the PBI measures, including urban residence, number of years of occupation and social class. In particular, given the potential importance of the period 1966–1976 (Cultural Revolution) on families (Kleinman, 1986), we looked for an effect of the age of the subjects on perceived parenting scores. We also wanted to see whether the number of children in the subjects' families might contribute to variation in scores, and whether the introduction of China's one-child policy might have had an impact on scores.

Applying a correction threshold for multiple testing, we observed no effect of origin (rural versus urban address) on any of the PBI measures. Similarly, we found no significant effect of years of education, nor of social status, on any PBI measure. We also found no effect of age on any PBI measure, nor any significant differences in PBI measures for those who would have been children (under the age of 18) during the Cultural Revolution, compared to those who were either born afterwards or were older than 18 at that period. Six percent of our sample were singletons, but we found no effect of the number of children in the subject's family on the reported PBI measures.

Association of parenting with risk for MD

Main effects and interactions

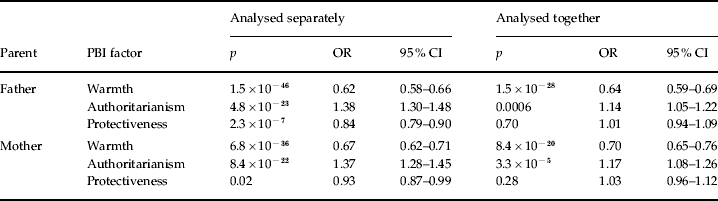

We began by testing for an association between each PBI factor individually and risk for MD separately in mothers and fathers. As shown in Table 2, in both parents, high levels of Warmth and Protectiveness reduced and high levels of Authoritarianism increased susceptibility for MD. The protective effect of Warmth was slightly greater in fathers than in mothers and a similar but somewhat larger difference was seen for Protectiveness. The pathogenic effects of high Authoritarianism were nearly identical in the two parents.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (ORs) for the association between paternal and maternal parenting dimensions and major depression (MD) examined separately, both one at a time and all together

ORs with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values (p) for the effect of three Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) dimensions on MD. Factors were standardized before analysis so that the OR represents the increase in risk for MD associated with an increase of one standard deviation in the relevant parenting dimension.

The three dimensions of parenting were significantly correlated. In fathers, the correlations were as follows (all highly significant at p<0.00001): Warmth–Protectiveness +0.36 Warmth–Authoritarianism −0.50 and Protectiveness–Authoritarianism −0.23. In mothers, the correlations were broadly similar (all highly significant at p<0.00001): Warmth–Protectiveness +0.29, Warmth–Authoritarianism −0.51 and Protectiveness–Authoritarianism −0.15. It was therefore of interest to determine, using multiple regression analyses, the effect of each dimension of parenting controlling for the other two dimensions. These results are also shown in Table 2.

In these joint analyses, the protective effect of Warmth on risk for MD was only slightly attenuated in both fathers and mothers. For Authoritarianism, the association with risk for MD declined substantially but remained highly significant in both parents. By contrast, the impact of Protectiveness on risk for MD disappeared in both mother and father.

Paternal and maternal effects considered jointly

The ratings of received parenting from mothers and fathers were highly correlated: Warmth +0.67, Authoritarianism +0.77 and Protectiveness +0.84 (all highly significant at p<0.0001). It was therefore of interest to examine jointly the impact of paternal and maternal Warmth, Authoritarianism and Protectiveness. We first examined the main effects and then, in a separate analysis, explored the significance of any possible interactions.

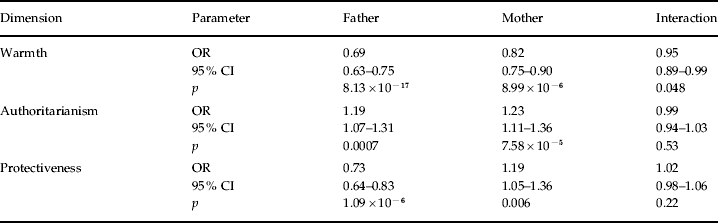

As shown in Table 3, when considered jointly, father's Warmth had a considerably stronger protective impact on risk for MD (OR 0.69) than did mother's Warmth (OR 0.82). Of note, a modestly significant positive interaction was also observed between paternal and maternal warmth. Interpreted in a positive direction, this means that, on the logistic scale, the protective effect on risk for MD of having both a mother and father with high Warmth was modestly greater than that predicted from the sum of the individual effects in mother and father taken on their own.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (ORs) for the association between paternal and maternal parenting dimensions and major depression (MD) examined together, first estimating only main effects and then estimating the interaction

ORs with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p values (p) for the effect of three Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI) factors on MD. Factors were standardized before analysis so that the OR represents the increase in risk for MD associated with an increase of one standard deviation in the relevant parenting dimension. Two models were run. The first examined only the main effects and those estimates are presented in the table. The second examined the main effects and the interaction and the estimates of the interaction from that analysis are depicted in the table.

When considered jointly, the pathogenic effect of maternal Authoritarianism was slightly stronger than that of paternal Authoritarianism and there was no evidence of an interaction. For Protectiveness, the results were very different. When examining paternal and maternal effects jointly, paternal Protectiveness remained protective, with an effect size (0.73) modestly greater than that observed when examined on its own (0.84). However, maternal Protectiveness changed sign and moved from being modestly protective when examined on its own (OR 0.92) to being associated with an increased risk for MD when paternal Protectiveness was included in the model (OR 1.19). Again, no significant interaction was observed.

Interactions between parenting dimensions

Finally, we examined interactions across dimensions, with a particular interest in evaluating Parker's hypothesis of the pathogenic effect for depression of what he termed ‘affectionless control’: the combination of low parental Warmth and high parental Protectiveness (Parker, 1979). Of the six possible two-way interactions between the three parenting dimensions, examined separately in mothers and fathers, one was significant (p<0.001) and consistent across both parents, a positive interaction between Authoritarianism and Protectiveness. That is, in the presence of high Authoritarianism (which is risk predisposing) and high Protectiveness (which is protective), the risk for MD is higher than would have been predicted by the main effects of the two parenting dimensions considered one at a time. Of the four remaining possible interactions, only one was significant and that at a marginal level (p=0.03). In fathers only, a positive interaction was observed between Warmth and Authoritarianism such that the joint effect of the two produced a higher risk for MD than would be predicted from the two dimensions taken one at a time.

Discussion

We examined, in a large sample of Chinese women, the relationship between risk for recurrent MD and three dimensions of retrospectively reported parenting received from their mothers and their fathers. We began by examining the factor structure of the PBI, the instrument we used to assess parenting. We identified in our Chinese sample a three-factor solution with individual factors representing parental Warmth, Protectiveness and Authoritarianism. This three-factor PBI solution found by Kendler et al. (1997) has been replicated in two other US samples (Cox et al. 2000; Lizardi & Klein 2002), and also in Japan (Sato et al. 1999) and Brazil (Terra et al. 2009). Although based on only a single sample and a single instrument, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that the broad dimensions of parenting are similar across culturally diverse human populations.

We assessed the independent association between the three parenting factors, separately in mothers and fathers, and the risk for MD. Consistent with a wide array of prior studies (Parker, 1979; Perris et al. 1986; Plantes et al. 1988; Parker & Hadzi-Pavlovic, 1992; Oakley-Browne et al. 1995; Rey, 1995; Rodgers, 1996a, b; Kendler et al. 2000), the most robust association we observed was an inverse one between Warmth and depressive risk. The magnitude of the association can be perhaps be best expressed by reversing the dimension and calling it parental coldness (Kendler et al. 1997). In this case, a one standard deviation increase in coldness from mother or father was associated with a 50–60% increase in risk for MD, modestly greater than the 38–47% increased risk observed in a US female twin population that included exactly this same scale analyzed in the same manner (Kendler et al. 2000).

Similar to other studies in Western populations (Oakley-Browne et al. 1995; Rey 1995; Rodgers 1996a, b; Kendler et al. 2000), we also found that high levels of Authoritarianism were associated with an increased risk for MD. The ORs seen in our sample (1.38 in fathers and 1.37 in mothers) were very similar to those seen in the US twin sample studied by Kendler et al. (2000) (1.33 in fathers and 1.34 in mothers).

However, in our sample of Chinese women, high levels of Protectiveness from both mothers and fathers, when analyzed independently, were associated with a decreased risk for MD (ORs of 0.84 and 0.93 respectively). This is the opposite pattern of that observed in Western samples. For example, in the Virginia twins, high Protectiveness was associated with an increased risk of MD, significantly in mothers (OR 1.26) and non-significantly in fathers (OR 1.14). Of note, for all three of our dimensions, the association with MD was slightly stronger for paternal than for maternal parenting, suggesting that for women in China the father has a psychological role of at least as much importance in the child's life as does the mother.

We next observed correlations in the dimensions of received parenting separately in mothers and fathers. The positive correlations between Protectiveness and Authoritarianism (+0.36 in fathers and +0.29 in mothers) were similar to the averaged correlation reported by the Virginia sample (+0.31). However, in our sample the inverse correlation between Warmth and Authoritarianism was stronger (about −0.50) than that observed in the Virginia twin (−0.33). Of particular interest, whereas in the Virginia sample Warmth and Protectiveness were modestly negatively correlated (−0.11), in our Chinese sample these two dimensions of parenting were positively correlated (+0.36 in fathers and +0.29 in mothers). These results together suggest an important cultural difference in parenting between the USA and China. In the USA, parental Protectiveness is inversely related to Warmth and increases risk for MD in offspring, whereas in China, parental Protectiveness is positively related to Warmth and decreases risk for MD.

We also examined the joint effect of all three parenting dimensions on risk for MD. Although the impact of Warmth was slightly attenuated, the effects of Authoritarianism were substantially reduced and Protectiveness completely eliminated. These results are similar to those observed in the Virginia female twin sample (Kendler et al. 2000). In both samples, the most robust and consistent relationship between parenting and risk for MD was parental Warmth. However, as noted earlier, whereas in China high parental Protectiveness can be thought of as a proxy for parental warmth and lovingness, in the USA high parental Protectiveness is a proxy for low levels of parental warmth and care.

The three levels of parenting were highly correlated in mothers and fathers, most strongly for Protectiveness and least for Warmth. It was therefore of interest to examine the impact of each parent's rearing practices, taking account of that of their spouse. These analyses could also examine interactions between paternal and maternal parenting styles, some of which have been hypothesized to be particularly pathogenic. A parenting style characterized by high levels of control and protectiveness and low levels of warmth (referred to as ‘affectionless control’) has been hypothesized to be particularly pathogenic with respect to risk for MD (Parker 1979; Mackinnon et al. 1993; Sato et al. 1998). In addition, a warm loving relationship with one parent might mitigate the impact of a poor relationship with the other parent. If so, this would predict an interaction between maternal and paternal Warmth in the prediction of MD.

When parental and maternal parenting dimensions were examined jointly, we found that the association between paternal Warmth and MD was stronger than that found for maternal Warmth. Most surprisingly, when examined jointly, high paternal Protectiveness remained protective and associated with a reduced risk for MD. However, when controlling for levels of paternal Protectiveness, high maternal Protectiveness, now more consistent with results in Western countries, becomes associated with an elevated risk of MD.

The examination of interactions between parenting was generally less informative. As seen previously in the Virginia twin sample (Kendler et al. 2000), we found no evidence for the concept of ‘affectionless control’ that the combination of low parental Warmth and high parental Protectiveness or Authoritarianism was more pathogenic than the main effects of these parenting dimensions examining in isolation.

Our findings can be usefully compared with those of the one other study in East Asia examining the association between PBI and lifetime MD of which we are aware. In 418 employed Japanese adults, Narita et al. (2000) found support for the three-factor solution of the PBI that we also observed in this study. The strongest association they observed was between low parental Warmth and risk for MD. Controlling for levels of Warmth, no significant effects were seen for Authoritarianism (which they had labeled in reverse direction ‘encouragement of behavioral freedom’). One significant effect was seen for Protectiveness (which they had labeled ‘denial of psychological autonomy’). In opposition to our findings, they found that high paternal Protectiveness increased risk for MD in women. Our findings, which require confirmation, suggest interesting differences in Chinese women that may not be shared with other East Asian populations, in the meaning of Protectiveness when received from their father.

There are several ways that perceived parenting could be linked to susceptibility to MD. For example, parenting abilities of mothers with postnatal depression could be perceived differently from those who do not suffer postnatal depression. We were not able to explore whether perinatal depression in the mothers of cases could be a link between onset of MD and perceived maternal parenting, but we were able to explore the impact of perinatal depression in cases themselves, and found no detectable effect (Tian et al. 2011).

To what extent do our findings reflect differences in parenting styles between Asian and Western parents? Although there is a dearth of studies relevant to adult psychopathology in China, there has been interest in the effects of parenting on child development and school achievement, providing instructive comparison with our results. Typically, these investigations use a different parenting typology from ours, distinguishing between authoritarian and authoritative styles (Baumrind, 1971). The former is characterized by low warmth, restricting the child's independence, and the frequent use of coercive discipline, thus conceptually similar to parents scoring low on the Warmth and high on the Authoritarianism scale of the PBI; the latter is characterized by high warmth and acceptance, respecting the child's autonomy and setting reasonable limits on behavior. These features are a combination of high scores on the Warmth and Protectiveness scales derived from the PBI.

Most studies examining the effect of parenting on children's academic, social and psychological adjustment have found patterns similar to those obtained in the West (Chen et al. 1997, 2000; Lai & McBride-Chang, 2001), but some have argued that Western categorizations of parenting styles do not capture the full range of parenting variation found in mainland China (Chao, 1994, 2000; Stewart et al. 1998; Wu et al. 2002). Our findings for the effect of Protectiveness as a proxy for parental warmth and lovingness, rather than increasing risk for MD as it does in the West, may reflect a mixed authoritarian and authoritative parenting style.

Our results add to the discussion about the similarities and dissimilarities between MD in China and the rest of the world. Kleinman has pointed out that ‘culturally coded symptoms may confound diagnosis’ (Kleinman, 2004) and has written extensively about the difference in the ways mood is conceptualized and expressed in China (Kleinman, 1986). Lee (1999) points out how psychiatric diagnoses, including MD, are in part the product of vested interests, political strategies and social policies in China; Phillips, Zhang and co-workers have explored the relationship between suicide in depression in China, demonstrating the importance of cultural factors in contributing to psychiatric disease (Phillips et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2004, 2010). Our work shows how factors known to predispose to MD in the West operate in China, sometimes in expected ways, sometimes unexpected.

Limitations

These results should be interpreted in the context of four potentially important methodological limitations. First, the sample is entirely female and our results may or may not extrapolate to men in China. Second, we were missing PBI data on a non-trivial proportion of our sample, with much higher missingness in our cases than our controls. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many of these cases had childhoods that were so deprived and stressful that the traditional PBI questions about parent–child relationships were not meaningful. The constructs of parenting assessed by the PBI were not sensible for them in the conditions in which they grew up. These missing data, however, are more likely to lead to an underestimation of the association between poor parenting on risk for MD than an overestimation.

Third, because of the retrospective nature of our data, we could not determine the degree to which the association between reporting parenting and history for MD is causal or a result of (a) retrospective recall bias, (b) passive gene–environment correlation in which depressed individuals parent poorly and pass on their risk genes to their children or (c) other confounding factors that might predispose to both poor parenting and MD. Correlations between contemporaneously recorded child-rearing practices and later recall are moderate (McCrae & Costa, 1988; Dunn & McGuire, 1994), as are the levels of agreement between relatives in retrospectively reported parenting (Parker, 1981, 1983; Schwarz et al. 1985). Reports of retrospective parenting are generally stable over time (Parker, 1989; Wilhelm et al. 2005). Although skepticism about retrospective reporting of parenting is certainly appropriate, we suggest that the reports on parenting analyzed here probably have sufficient reliability and validity to be seriously considered as a reflection of true parenting and a true causal influence on risk for MD (McCrae & Costa, 1988; Parker, 1989).

Fourth, in this report we have emphasized comparisons between data from our current sample and those obtained in the Virginia twins. This is a useful comparison because both samples were entirely female, and the studies used the same PBI items and closely related statistical methods. However, it is important to note that, whereas the Virginia sample is population based, the Chinese sample is clinically ascertained and the cases of MD in our Chinese sample would be expected on average to be more severe.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust. The authors are part of the CONVERGE consortium and gratefully acknowledge the support of all partners in hospitals across China.

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph. 1971;4:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Burbach DJ, Borduin CM. Parent-child relations and the etiology of depression: a review of methods and findings. Clinical Psychology Reviews. 1986;6:133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65:1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2000;21:233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chen RC. Vulnerability of factors of depression among college students in Taiwan. Chinese Journal of Mental Health. 1991;5:53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Dong Q, Zhou H. Authoritative and authoritarian parenting practices and social and school performance in Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21:855–873. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu M, Li B, Cen G, Chen H, Wang L. Maternal authoritative and authoritarian attitudes and mother–child interactions and relationships in urban China. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Enns MW, Clara IP. The Parental Bonding Instrument: confirmatory evidence for a three-factor model in a psychiatric clinical sample and in the National Comorbidity Survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:353–357. doi: 10.1007/s001270050250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:85. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan C, Sham P, Minne C, Lee A, Murray R. Quality of parenting and vulnerability to depression: results from a family study. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:185–191. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, McGuire S. Hetherington E. M., Reiss D., Plomin R. Separate Social Worlds of Siblings: The Impact of Nonshared Environment on Development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. Young children's nonshared experiences: a summary of studies in Cambridge and Colorado; pp. 111–128. ), pp. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlsma C, Emmelkamp PMG, Arrindell WA. Anxiety, depression, and perception of early parenting: a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10:251–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kao YM, Wu CI, Lue BH. The relationships between inept parenting and adolescent depression dimension and conduct behaviors. Chinese Journal of Family Medicine. 1998;8:11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Parenting: a genetic-epidemiologic perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:11–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:109–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA. Parenting and adult mood, anxiety and substance use disorders in female twins: an epidemiological, multi-informant, retrospective study. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:281–294. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Sham PC, MacLean CJ. The determinants of parenting: an epidemiological, multi-informant, retrospective study. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:549–563. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Social Origins of Distress and Disease. Depression, Neurasthenia and Pain in Modern China. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. Culture and depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:951–953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KW, McBride-Chang C. Suicidal ideation, parenting style, and family climate among Hong Kong adolescents. International Journal of Psychology. 2001;36:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Diagnosis postponed: shenjing shuairuo and the transformation of psychiatry in post-Mao China. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 1999;23:349–380. doi: 10.1023/a:1005586301895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y-L. Parent–child interaction and children's depression: the relationships between parent–child interaction and children's depressive symptoms in Taiwan. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26:447–457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizardi H, Klein DN. Evidence of increased sensitivity using a three-factor version of the Parental Bonding Instrument. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:619–623. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A, Henderson AS, Andrews G. Parental ‘affectionless control’ as an antecedent to adult depression: a risk factor refined. Psychological Medicine. 1993;23:135–141. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700038927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Do parental influences matter? A reply to Halverson. Journal of Personality. 1988;56:445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Narita T, Sato T, Hirano S, Gota M, Sakado K, Uehara T. Parental child-rearing behavior as measured by the Parental Bonding Instrument in a Japanese population: factor structure and relationship to a lifetime history of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;57:229–234. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley-Browne MA, Joyce PR, Wells JE, Bushnell JA, Hornblow AR. Adverse parenting and other childhood experience as risk factors for depression in women aged 18–44 years. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;34:13–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)00099-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental characteristics in relation to depressive disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;134:138–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental reports of depressives. An investigation of several explanations. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1981;3:131–140. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(81)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental Overprotection: A Risk Factor in Psychosocial Development. Grune & Stratton; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. The Parental Bonding Instrument: psychometric properties reviewed. Psychiatric Developments. 1989;7:317–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Parental representations of melancholic and non-melancholic depressives: examining for specificity to depressive type and for evidence of additive effects. Psychological Medicine. 1992;22:657–665. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700038101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Tupling H, Brown L. A Parental Bonding Instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Perris C, Arrindell WA, Eisemann ME. Parenting and Psychopathology. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Perris C, Arrindell WA, Perris H, Eisemann M, van der Ende J, von Knorring L. Perceived depriving parental rearing and depression. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;148:170–175. doi: 10.1192/bjp.148.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002;360:1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantes MM, Prusoff BA, Brennan J, Parker G. Parental representations of depressed outpatients from a U.S.A. sample. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;15:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM. Perceptions of poor maternal care are associated with adolescent depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;34:95. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B 1996aReported parental behaviour and adult affective symptoms. 1. Associations and moderating factors Psychological Medicine 2651–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B 1996bReported parental behaviour and adult affective symptoms. 2. Mediating factors Psychological Medicine 2663–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Narita T, Hirano S, Kusunoki K, Sakado K, Uehara T. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Parental Bonding Instrument in a Japanese population. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:127–133. doi: 10.1017/s003329179800779x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Sakado K, Uehara T, Narita T, Hirano S, Nishioka K, Kasahara Y. Dysfunctional parenting as a risk factor to lifetime depression in a sample of employed Japanese adults: evidence for the ‘affectionless control’ hypothesis. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:737–742. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797006430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JC, Barton-Henry ML, Pruzinsky T. Assessing child-rearing behaviors: a comparison of ratings made by mother, father, child, and sibling on the CRPBI. Child Development. 1985;56:462–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SM, Rao N, Bond MH. Chinese dimensions of parenting: broadening Western predictors and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology. 1998;33:345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terra L, Hauck S, Schestatsky S, Fillipon AP, Sanchez P, Hirakata V, Ceitlin LH. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Parental Bonding Instrument in a Brazilian female population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;43:348–354. doi: 10.1080/00048670902721053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian T, Li Y, Xie D, Shen Y, Ren J, Wu W, Guan C, Zhang Z, Zhang D, Gao C, Zhang X, Wu J, Deng H, Wang G, Zhang Y, Shao Y, Rong H, Gan Z, Sun Y, Hu B, Pan J, Sun S, Song L, Fan X, Zhao X, Yang B, Lv L, Chen Y, Wang X, Ning Y, Shi S, Kendler KS, Flint J, Tian H. Clinical features and risk factors for post-partum depression in a large cohort of Chinese women with recurrent major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.047. . Published online 6 August 2011. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Niven H, Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. The stability of the Parental Bonding Instrument over a 20-year period. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35:387–393. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Robinson CC, Yang C, Hart CH, Olsen SF, Porter CL, Jin S, Wo J, Wu J. Similarities and differences in mothers' parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:481–491. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Conwell Y, Zhou L, Jiang C. Culture, risk factors and suicide in rural China: a psychological autopsy case control study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;110:430–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Li N, Tu XM, Xiao S, Jia C. Risk factors for rural young suicide in China: a case-control study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;129:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]