ABSTRACT

Whether gestational protein restriction affects the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in uterine artery remains unknown. In this study, we hypothesized that gestational protein restriction alters the expression of RAS components in uterine artery. In study one, time-scheduled pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were fed a normal or low-protein (LP) diet from Day 3 of pregnancy until they were killed at Days 19 and 22. The uterine arteries were collected and used for gene expression of Ace, Ace2, Agtr1a, Agtr1b, Agtr2, Esr1, and Esr2 by quantitative real-time PCR and/or Western blotting. LP increased plasma levels of angiotensin II in pregnant rats. In the uterine artery, the expressions of Agtr1a, Agtr1b, and Esr1 were increased by LP at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy, whereas the abundance of AGTR1 and AGTR2 was increased by LP at Day 19 of pregnancy. The expression of Ace2 was not detectable in rat uterine artery. In study two, virgin female rats were ovariectomized and implanted with either 17beta-estradiol (E2), progesterone (P4), both E2 and P4, or placebo pellets until they were killed 7 days later. In rat uterine artery, E2 and P4 reduced the expression of Agtr1a, and E2 increased the expression of Agtr1b and Agtr2, but neither E2 nor P4 regulated the expression of Ace. These results indicate that gestational protein restriction induces an increase in Agtr1 expression in uterine artery, and thus may exacerbate the vasoconstriction to elevated angiotensin II present in maternal circulation, and that female sex hormones also play a role in this process.

Keywords: angiotensin I converting enzyme, angiotensin II/angiotensin II receptor, developmental origins of health and disease, gestational protein restriction, nutrition, pregnancy, rat, uterine artery

Gestational protein restriction increases plasma levels of angiotensin II and AGTR1 and AGTR2 protein levels in late pregnancy; estrogen plays a role in regulating the expression of angiotensin II receptors in rat uterine artery.

INTRODUCTION

During normal pregnancy, the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is activated, and its different components demonstrate progressive changes [1–4]. Besides its critical role in regulating sodium and water homeostasis, RAS, particularly in kidney, has been reported recently to play an important role in fetal programming of hypertension in response to hormonal manipulations [5, 6]; dietary manipulation, such as maternal global nutrient restriction [7] or protein restriction [8]; and uteroplacental insufficiency [9] during gestation. Accumulating evidence indicates that RAS in hypertensive offspring affected by intrauterine growth restriction or maternal protein restriction was altered either systemically or locally [9–13]. However, to date, it is unclear whether and how RAS affects maternal cardiovascular function and metabolism in response to nutritional or hormonal disruption.

Uterine artery remodeling and corresponding uteroplacental blood flow play a critical role in uterine, placental, and fetal growth during pregnancy. Uterine blood flow is a determinant of fetal growth and survival [14]. Maternal vascular remodeling ensures adequate placental perfusion by transforming maternal arteries, including uterine artery, into low-resistance, large-caliber vessels. Physiologically, uterine artery dilation during pregnancy is achieved partly, if not wholly, by increased 17β-estradiol (E2) levels and local nitric oxide production, and reduced vasoactive response to serotonin [15]. Global dietary restriction leads to a remarkable reduction in uterine and placental blood flow [16], and protein restriction itself impairs vascular relaxation of mesenteric artery in pregnant rats [17], resulting in fetal growth retardation. In addition, limited studies demonstrate that RAS regulates vasoconstriction in uterine artery. In mice, the contractile response in uterine artery to angiotensin II is elevated in mid and late pregnancy, and vasoconstriction is mainly mediated by angiotensin II receptor, type 1 (AGTR1) and modulated by angiotensin II receptor, type 2 (AGTR2) [18, 19].

Our laboratory and others have reported that maternal protein restriction, albeit to a different extent in the reduction of protein in diet, causes the development of hypertension in offspring [8, 20–25]. Although the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, it is known that a low-protein diet alters endocrine status in pregnant rats, including elevated plasma levels of testosterone and estradiol [26] and reduced plasma levels of progesterone [27, 28]. The altered endocrine status may have an impact on maternal RAS function. For instance, estradiol, mainly via estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1), regulates the expression of RAS in a tissue-specific manner, with reduced expression of angiotensin I-converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) 1 (Ace1) and angiotensin I-converting enzyme (peptidyl-dipeptidase A) 2 (Ace2) in kidney; reduced expression of angiotensin II receptor, type 1a (Agtr1a) in hypothalamus and anterior pituitary; increased expression of Agtr1a and Agtr2 in kidney; and unaltered expression of Ace, Ace2, Agtr1, and Agtr2 in lung [29–33]. So far, it is unknown whether estrogen regulates expression of RAS in uterine artery; however, the presence and/or function of ESR1 [34–36], AGTR1, and AGTR2 [18, 19, 37, 38] in the uterine artery support this possibility.

In this study, we hypothesized that gestational protein restriction and associated changes in female sex hormones may alter the expression of RAS in rat uterine artery. The objectives were to investigate the gene expression of Ace, Ace2, Agtr1a, Agtr1b, Agtr2, Esr1, and estrogen receptor 2 (ER beta; Esr2) in uterine artery in response to gestational protein restriction and to assess whether the expression of these genes is altered by estradiol and progesterone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Experimental Designs

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch and were in accordance with those published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1996). In study one, timed pregnant Sprague Dawley rats weighing between 175 and 225 g were purchased from Harlan (Houston, TX). At Day 3 of pregnancy, rats were randomly divided into two dietary groups, housed individually, and fed a control (CT; 20% casein) or low-protein (LP; 6% casein) diet until they were killed on Day 19 or 22 of pregnancy (n = 5 rats per diet per day of pregnancy). The isocaloric low-protein and normal-protein diets were purchased from Harlan Teklad (cat. TD.90016 and TD.91352, respectively; Madison, WI). Fetal weights were recorded. The plasma from pregnant rats was collected for angiotensin II enzyme immunoassay. In study two, virgin female rats were ovariectomized, recovered for 5 days, then implanted with either E2 (0.5 mg, 21-day release [OVX + E2 group]), progesterone (P4; 5 mg, 21-day release [OVX + P4 group]), both E2 and P4 (OVX + E2 + P4 group), or placebo pellets (OVX group; n = 5 rats per treatment). All animals were killed 7 days after pellet insertion. The procedures of ovariectomy, hormonal replacement, and efficacy of these procedures were described by Ross et al. [39]. The plasma levels of E2 and P4 in this study were similar to those we reported previously using a similar experimental design [39].

In both studies, the main uterine artery was separated carefully from surrounding tissues, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analyzed. The procedures for dissecting the uterine artery were described by Mandala et al. [40].

Angiotensin II Enzyme Immunoassay

Angiotensin II enzyme immunoassay kit (cat. EK-002-12; Phoenix Pharmaceutical Inc., Burlingame, CA) was used for measuring the concentration of angiotensin II in rat plasma. A total of 50 μl of rat plasma in duplicate was used for this assay. All of the procedures were conducted according to the instructions of the assay kit.

RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA from the whole piece of uterine artery (n = 4–5 rats per diet per sex per day of pregnancy) was extracted by Trizol reagent (cat. 15596-018; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The possible genomic DNA in total RNAs was digested with RNA-free DNase I (cat. 79254; Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), followed by cleanup procedures using a Qiagen RNeasy minikit (cat. 74104; Qiagen). All of these procedures were completed by following the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by RT in a total volume of 20 μl by using a MyCycler Thermal Cycler (cat. 170-9703; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) under the following conditions: one cycle at 28°C for 15 min, 42°C for 50 min, and 95°C for 5 min.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR detection was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (cat. 184-5096; Bio-Rad). TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for rat Ace (Rn00561094_m1), Ace2 (Rn01416289_m1), Agtr1a (Rn01435427_m1), Agtr1b (Rn02132799_s1), Agtr2 (Rn00560677_s1), Esr1 (R00664737_m1), Esr2 (Rn00562610_m1), and supermix reagents were from Applied Biosystems (Carlsbad, CA). The reaction reagent mixture was incubated at 50°C for 2 min, heated to 95°C for 10 min, and cycled according to the following parameters: 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles. Rn18s served as an internal control to standardize the amount of sample RNA added to a reaction. The primers for rat Rn18s are 5′-gctgagaagacggtcgaact-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-ttaatgatccttccgcaggt-3′ (reverse primer). SYBR Green Supermix (cat. 170-8882; Bio-Rad) was used for amplification of Rn18s. The mixture of reaction reagents was incubated at 95°C for 10 min and cycled according to the following parameters: 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles. Negative control without cDNA was performed to test primer specificity. The relative gene expression was calculated by use of the threshold cycle (CT) Rn18s/CT target gene.

Protein Preparation

Considering the heterogeneity of uterine artery [41], protein was extracted from the same uterine arteries where the total RNAs were prepared, as described previously [42]. Briefly, proteins were precipitated from organic phase in the RNA preparation procedure. All of the procedures followed the manufacturer's protocol. The final protein pellets were dissolved in resuspension buffer (2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 50 mM Tris, pH 7.8).

Western Blotting

Aliquots of 20 μg of protein and 4× NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (cat. NP0007; Invitrogen) were combined and subjected to electrophoresis with NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Gel (cat. NP0006; Invitrogen) and MOPS SDS Running Buffer (cat. NP0001; Invitrogen). Briefly, the separated proteins in SDS-PAGE were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 4°C overnight. After blocking in 5% nonfat milk, a rabbit anti-ACE1 polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG; cat. PT344R; Panora Biotech, Sugarland, TX) at 1:1000 dilution, a goat anti-AGTR1 polyclonal IgG (cat. Sc-31181; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), or a rabbit anti-AGTR2 polyclonal IgG (sc-9040; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:200 dilution was added to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. 1030-05; SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) or HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (cat. 6420-05; SouthernBiotech) at 1:5000 dilution at room temperature for 1 h. Proteins in blots were visualized with Pierce enhanced chemiluminescence detection (cat. 32209; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) and Blue Lite Autorad Film (cat. F9024; BioExpress, Kaysville, UT) according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Beta-actin (ACTB) was used as an internal control for Western blotting in this study. Primary antibody—mouse monoclonal antibody for ACTB (cat. 3700; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA)—and secondary antibody—HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (cat. 1030-05; SouthernBiotech)—were used at 1:10 000 and 1:5000 dilutions, respectively. Visualization of proteins in blots was the same as mentioned above. Blots were incubated with stripping buffer (cat. 46430; Thermo Scientific) at room temperature for 15 min, followed by blocking in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h. The blots were incubated with a rabbit anti-ACE2 polyclonal IgG (cat. ab87436; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA) at 1:1000 dilution at room temperature for 2 h. The following procedures were the same as those for ACE analysis.

The signals in films representing the contents of the target proteins ACE, AGTR1, and AGTR2, as well as the internal control protein ACTB, were densitometrically quantified by using Fluorchem 8000 software (Cell Biosciences, Santa Clara, CA). The relative amount of target protein was calculated by the ratio of total densitometrical value of target protein to that of ACTB in each rat uterine artery analyzed by Western blotting.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data were subjected to least-squares ANOVA by using the general linear models procedures of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data on fetal-placental weight, plasma levels of angiotensin II, and gene expression were analyzed for effects of day of pregnancy, diet treatment, and their interaction. Data from steroid hormone supplementation were analyzed using preplanned orthogonal contrasts (OVX + P4 vs. OVX, OVX + E2 vs. OVX, and OVX + P4 + E2 vs. OVX). A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant, whereas a P value of 0.05 to 0.10 was considered to represent a trend toward significance. Data in tissue weights are presented as means with standard errors, whereas data in gene expression are presented as least-squares means with overall standard errors (SEM).

RESULTS

Fetal Growth Was Impaired by Maternal Protein Restriction

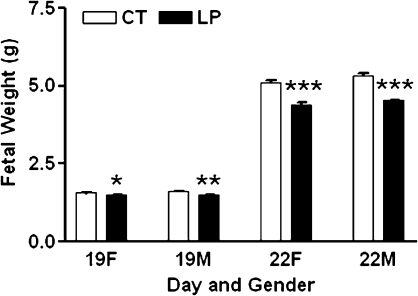

Fetal weights are shown in Figure 1. Weights of both male and female fetuses in the LP group were lower than those in the CT group at both Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy (P < 0.05).

FIG. 1.

Fetal weights in rats with (LP) or without (CT) gestational protein restriction at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

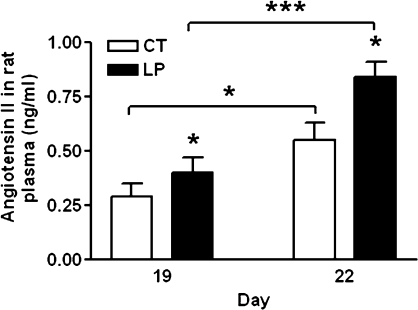

Plasma Levels of Angiotensin II in Pregnant Rats Were Increased by Maternal Protein Restriction

At Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy, the plasma levels of angiotensin II in the LP group were increased (P < 0.05) by 1.4-fold and 1.5-fold compared with those in the CT group, respectively. In the LP and CT groups, the plasma levels of angiotensin II at Day 22 of pregnancy were increased by 1.9-fold and 2.1-fold, respectively, compared with those at Day 19 of pregnancy (P < 0.05, P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Plasma levels of angiotensin II in pregnant rats with (LP) or without (CT) gestational protein restriction. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

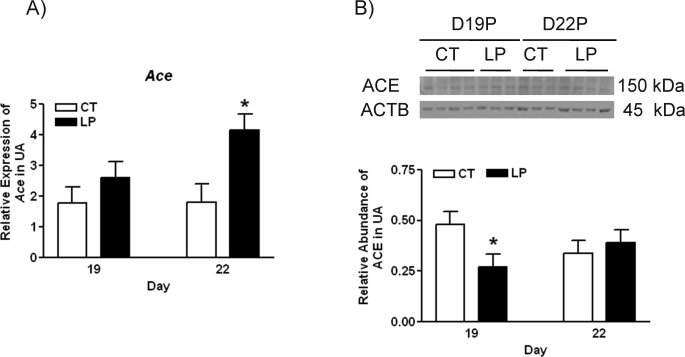

Expression of Ace in Rat Uterine Artery

For the LP group, the mRNA levels of Ace in uterine artery were not changed by Day 19 of pregnancy, but increased 2.3-fold (P < 0.05) by Day 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 3A), whereas the abundance of ACE protein was decreased by 1.7-fold in the LP group at Day 19 of pregnancy, and not changed by diet at Day 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 3B). Both Ace2 mRNAs and protein were not detectable in rat uterine artery by quantitative PCR and Western blotting, respectively (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Expressions of Ace in rat uterine artery with (LP) or without (CT) gestational protein restriction at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy. A) Quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA levels of Ace. The error bar represents the least mean ± SEM expressed as relative units of mRNA standardized against Rn18s (n = 6). B) Western blot analysis of ACE protein. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as the ratio of the density of the ACE band to that of ACTB (n = 3–4). *P < 0.05.

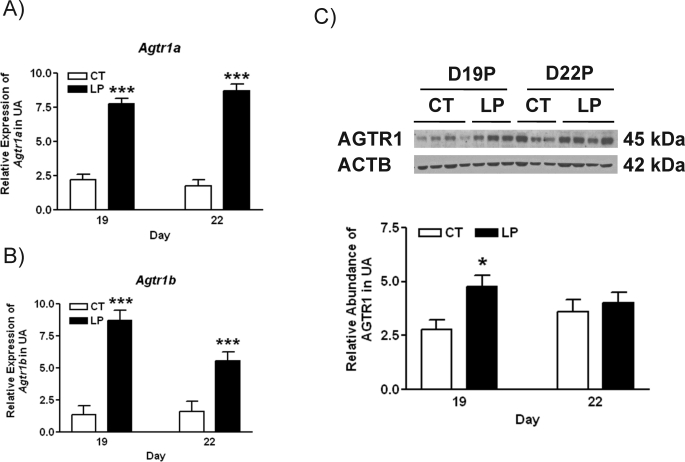

Expression of Agtr1a, Agtr1b, Agtr2, Esr1, and Esr2 in Rat Uterine Artery

The mRNA levels of Agtr1a in uterine artery were increased by 3.5-fold (P < 0.001) and 5.0-fold (P < 0.001) in the LP group at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy, respectively (Fig. 4A). The expression of Agtr1b in uterine artery was also increased in the LP group by 6.4-fold (P < 0.001) and 3.5-fold (P < 0.001) at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy, respectively (Fig. 4B). The abundance of AGTR1 protein in rat uterine artery was increased by 1.7-fold in the LP group compared with the CT group at Day 19 of pregnancy, but not changed by diet at Day 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Expressions of Agtr1 in rat uterine artery with (LP) or without (CT) gestational protein restriction at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy. A) Quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA levels of Agtr1a. B) Quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA levels of Agtr1b. The error bar represents the least mean ± SEM expressed as relative units of mRNA standardized against Rn18s (n = 6). C) Western blot analysis of AGTR1 protein. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as the ratio of density of the AGTR1 band to that of ACTB (n = 3–4). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

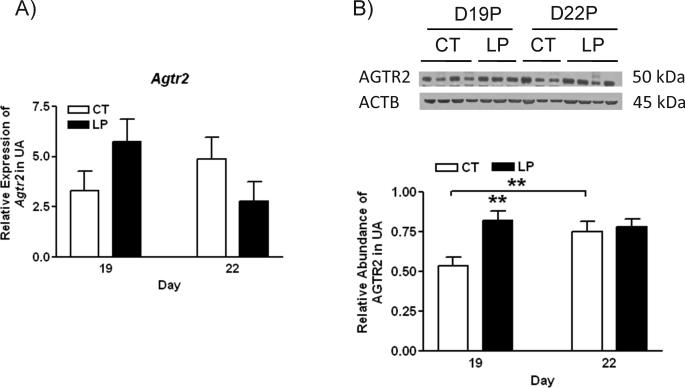

The mRNA levels of Agtr2 were not changed by diet at both Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the abundance of AGTR2 in rat uterine artery was increased by 1.5-fold in the LP group compared with the CT group at Day 19 of pregnancy and was not changed at Day 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Expressions of Agtr2 in rat uterine artery with (LP) or without (CT) gestational protein restriction at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy. A) Quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA levels of Agtr2. The error bar represents the least mean ± SEM expressed as relative units of mRNA standardized against Rn18s (n = 6). B) Western blot analysis of AGTR2 protein. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as the ratio of density of the AGTR2 band to that of ACTB (n = 3–4). **P < 0.01.

Expression of Esr1 and Esr2 in Rat Uterine Artery

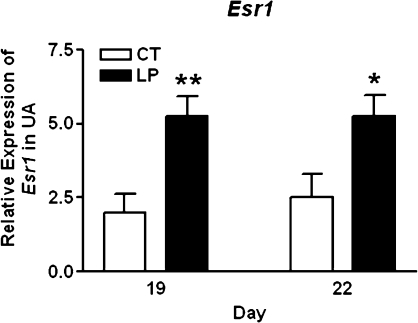

The expression of Esr1 was increased in the LP group by 2.6-fold (P < 0.001) and 2.1-fold (P < 0.05) at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy, respectively (Fig. 6A). The expression of Esr2 was marginally detectable by quantitative PCR, and CT value was in a range of 35.2–38.4 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Expressions of Esr1 in rat uterine artery with (LP) or without (CT) gestational protein restriction at Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy by quantitative PCR analysis. The error bar represents the least mean ± SEM expressed as relative units of mRNA standardized against Rn18s (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

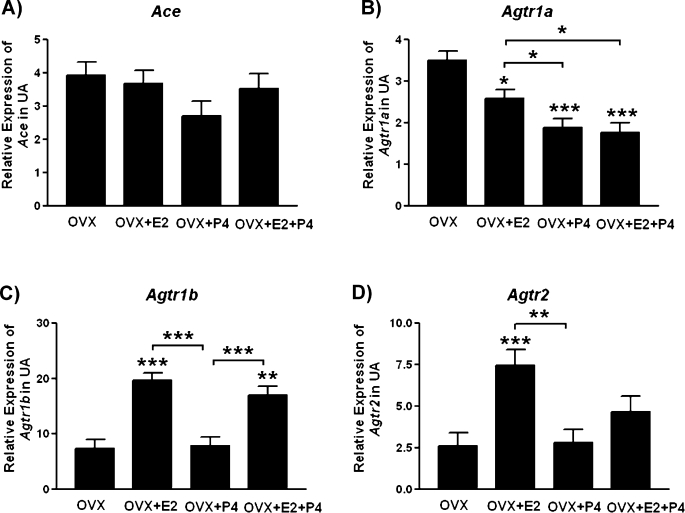

Expression of Ace, Agtr1a, Agtr1b, and Agt2 in Rat Uterine Artery Was Regulated by Female Sex Hormone

The expression of Ace was not changed by either E2 or P4 (Fig. 7A). Both E2 and P4 reduced the expression of Agtr1a by 1.4- and 1.9-fold, respectively (P < 0.05, P < 0.001; Fig. 7B); E2 increased the expression of Agtr1b by 2.5-fold (P < 0.001; Fig. 7C); and E2 increased the expression of Agtr2 by 2.9-fold (P < 0.001; Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

Hormonal regulation on the expressions of Ace (A), Agtr1a (B), Agtr1b (C), and Agtr2 (D) in rat uterine artery. The error bar represents the least mean ± SEM expressed as relative units of mRNA standardized against Rn18s (n = 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

This study, to our knowledge, reports for the first time that gestational protein restriction increases plasma levels of angiotensin II in pregnant dams and alters gene expression of RAS in uterine artery. Numerous studies examined the effects of maternal protein restriction on the RAS of the offspring, as reviewed by Moritz et al. [10]; however, whether gestational protein restriction affects the expression of RAS components and their functions on the maternal side has been largely ignored. This study shows that gestational protein restriction does affect RAS in pregnant dams and also provides a framework for the investigation of RAS function in response to gestational protein restriction. We suggest that these changes in RAS in response to gestational protein restriction may contribute to reduced vascular relaxation, and thus reduce blood flow to the uteroplacental unit, resulting in fetal growth restriction (Fig. 1).

Reductions in uterine arterial blood flow can occur through elevated angiotensin II levels in the plasma and/or elevated AGTR1 receptors in the uterine artery. Previous studies in late pregnant ewes have shown a reduction in uterine artery blood flow when plasma angiotensin II levels are elevated [43]. This study demonstrates elevated angiotensin II levels in the plasma for protein-restricted pregnant rats compared with controls. In the CT group, the plasma levels of angiotensin II were increased from Day 19 to Day 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 2). This is similar to the changes in angiotensin II in human pregnancy [44]. The LP diet did not alter this temporal pattern, but increased the plasma levels of angiotensin II compared with the CT group at both Days 19 and 22 of pregnancy (Fig. 2). The elevated angiotensin II levels may exacerbate arterial constriction by these following mechanisms: 1) The net bioavailability of angiotensin II for the uterine artery is increased in LP dams, when the elevated levels of circulating angiotensin II overcome the reduction in the local production of angiotensin II in uterine artery due to the decreased abundance of ACE protein by the LP diet (Fig. 3B). Angiotensin II binds to AGTR1 and finally causes vasoconstriction. 2) Angiotensin II up-regulates the expression of Agtr1 and down-regulates the expression of Agtr2 [45]. 3) The nonexpression of Ace2 in uterine artery (data not shown) makes it impossible to convert angiotensin II to angiotensin (1–7) and reduce the angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction. 4) In the long term, angiotensin II promotes vascular smooth muscle proliferation via AGTR1 in arteries [3, 46, 47]. As a result, gestational protein restriction may stimulate uterine artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and differentiation.

In the vascular tissue, including uterine artery, AGTR1 and AGTR2 mediate the physiological function of angiotensin II, vasoconstriction or vasodilatation, respectively. Recently, it has been reported that AGTR2 may reduce AGTR1-mediated contractile response to angiotensin II in mouse uterine artery [18], possibly by stimulating nitric oxide production [48]. During mid and late pregnancy, the vasoconstricting response to angiotensin II, primarily mediated by AGTR1 [49], is increased in mouse uterine artery, although the AGTR2-mediated vasodilatation is increased as well [48]. Although it is known that the affinities of AGTR1 and AGTR2 to angiotensin II in rat heart are similar [50], in the uterine artery angiotensin II is suggested to interact primarily with AGTR1 instead of AGTR2 [51], because the inhibitory effect mediated by AGTR2 on vasoconstriction by AGTR1 is reduced in late pregnancy [52]. In ovine uterine artery, the AGTR1:AGTR2 ratio is increased during pregnancy [53]. This may indicate that AGTR1 may be predominant over AGTR2 in regulating vascular reactivity in the uterine artery. In this study, at Day 19 of pregnancy the abundance of both AGTR1 and AGTR2 proteins was increased by the LP diet (Figs. 4B and 5B), with the unaltered ratio of AGTR1 and AGTR2 in the LP group. Notably, AGTR1 proteins detected by Western blotting in this study contain the products of two genes, Agtr1a and Agtr1b, because the antibody cannot differentiate between the two proteins because of their high identity (95%) [54]. Agtr1a and Agtr1b are different genes, but they show high identity in both nucleotide and amino acid sequences [54], and their proteins mediate similar vasoconstrictions in response to angiotensin II [55, 56]. It has been reported that protein restriction impairs the vascular relaxation of mesenteric arteries in pregnant rats [17], and global dietary restriction reduces the uteroplacental blood flow [16]. Thus, it is reasonable to predict that the overall vasoconstriction in the LP uterine artery may be enhanced, and therefore the uterine blood flow is impaired in the LP group. This will be investigated in our future studies.

The expressions of Ace and Agtr2 in uterine artery may be regulated at the posttranscriptional level. The direct evidence in this study is that the protein and mRNA levels of these genes do not match well (Figs. 3 and 5). This phenomenon also occurs in these gene expressions in rat placental labyrinth zone [57]. Recently, several studies have demonstrated that gene expressions of RAS components, such as Ace and Agtr2, are posttranscriptionally regulated by microRNAs (miRNAs) [12, 13]. Up-regulation of miRNAs, mmu-MIR27A and mmu-MIR27B by maternal protein restriction reduces the ACE proteins in the brains of offspring [13]. However, to date, the existence of miRNAs regulating the expression of Ace in uterine artery has never been reported. As for the functional significance, the reduction of ACE protein at late pregnancy in response to gestational protein restriction may be an attempt to reduce the local angiotensin II levels, and increased AGTR2 proteins may promote vasodilatation. These may represent a positive adaptation to the maternal protein restriction when fetuses grow rapidly in late pregnancy. The underlying mechanisms warrant further investigation.

The expressions of Agtr1 and Agtr2 are regulated by female sex hormones. Pregnancy demonstrates remarkable changes in hormones, metabolism, and cardiovascular functions. It has been reported that gestational protein restriction increases the maternal plasma levels of estradiol [26] while reducing the plasma levels of progesterone [27, 28]. Accumulating evidence indicates that estrogen regulates gene expression of RAS components in a tissue-specific manner [29–33]. Estrogen stimulates renal Agtr1a and Agtr2 expression in rodents [29, 30]. In contrast, estrogen down-regulates expression of Agtr1a in hypothalamus [32]. Similarly, in this study we found that the expression of Agtr1a in uterine artery was reduced by both E2 and P4 (Fig. 7B). It has been reported that gestational protein restriction decreased the plasma levels of P4 in rat [27, 28]; therefore, the elevated expression of Agtr1a in response to gestational protein restriction may be caused partly by the reduced levels of P4 [27, 28], because angiotensin II also stimulates the expression of Agtr1 [45]. This study also demonstrates that estrogen increases the expression of Agtr1b and Agtr2 in rat uterine artery (Fig. 7, C and D). Further, the expression of Esr1 in the uterine artery was elevated in protein-restricted pregnant rats (Fig. 6). Thus, elevated expression of Esr1 and plasma levels of estrogen in protein-restricted mothers could have contributed to the increased expressions of Agtr1b in uterine artery. As a result, although estrogen is a potent vasodilator and critical for the cardiovascular adaption to pregnancy, estrogen-induced RAS changes in the uterine artery in response to gestational protein restriction failed to restore normal vasoactivity, as shown by the impaired vascular relaxation [17].

In summary, this study reveals that gestational protein restriction increases the maternal plasma levels of angiotensin II and Agtr1 expression in uterine artery, and thus may exacerbate the vasoconstriction in uterine artery, and that female sex hormones also play a role in this process. In future studies, the following relevant questions will be addressed: 1) Is the vasoconstricting response of uterine artery to angiotensin II elevated in rats with gestational protein restriction? 2) Which type of angiotensin II receptors play predominant roles in the vasoconstriction of uterine artery in vivo or ex vivo? 3) Can the altered expression of RAS by gestational protein restriction be reversed by supplementation or blockage of sex hormones? These answers will provide valuable information for the role of altered RAS in fetal programming on adulthood hypertension in response to nutritional disruptions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Ms. Elizabeth A. Powell for editorial work on this manuscript and administrative support.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL102866 and R01HL58144.

REFERENCES

- Brosnihan KB, Neves LA, Anton L, Joyner J, Valdes G, Merrill DC. Enhanced expression of Ang-(1–7) during pregnancy. Braz J Med Biol Res 2004; 37: 1255 1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnihan KB, Hering L, Dechend R, Chappell MC, Herse F. Increased angiotensin II in the mesometrial triangle of a transgenic rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension 2010; 55: 562 566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering L, Herse F, Geusens N, Verlohren S, Wenzel K, Staff AC, Brosnihan KB, Huppertz B, Luft FC, Muller DN, Pijnenborg R, Cartwright JE, et al. Effects of circulating and local uteroplacental angiotensin II in rat pregnancy. Hypertension 2010; 56: 311 318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Yagil Y, Bursztyn M, Barkalifa R, Scharf S, Yagil C. ACE2 expression and activity are enhanced during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 295: R1953 R1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz KM, Johnson K, Douglas-Denton R, Wintour EM, Dodic M. Maternal glucocorticoid treatment programs alterations in the renin-angiotensin system of the ovine fetal kidney. Endocrinology 2002; 143: 4455 4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrwoll CS, Mark PJ, Mori TA, Puddey IB, Waddell BJ. Prevention of programmed hyperleptinemia and hypertension by postnatal dietary omega-3 fatty acids. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 599 606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JS, Ford SP, Lang AL, Pahl LR, Drumhiller MC, Babcock SA, Nathanielsz PW, Nijland MJ. Nutrient restriction impairs nephrogenesis in a gender-specific manner in the ovine fetus. Pediatr Res 2007; 61: 42 47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci 1999; 64: 965 974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigore D, Ojeda NB, Robertson EB, Dawson AS, Huffman CA, Bourassa EA, Speth RC, Brosnihan KB, Alexander BT. Placental insufficiency results in temporal alterations in the renin angiotensin system in male hypertensive growth restricted offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007; 293: R804 R811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz KM, Cuffe JS, Wilson LB, Dickinson H, Wlodek ME, Simmons DG, Denton KM. Review: sex specific programming: a critical role for the renal renin-angiotensin system. Placenta 2010; 31 (suppl): S40 S46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Galffy A, Field SA, Gheorghe CP, Mittal A, Longo LD. Maternal protein deprivation: changes in systemic renin-angiotensin system of the mouse fetus. Reprod Sci 2009; 16: 894 904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Lister R, Leitzke A, Goyal D, Gheorghe CP, Longo LD. Antenatal maternal hypoxic stress: adaptations of the placental renin-angiotensin system in the mouse. Placenta 2011; 32: 134 139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Goyal D, Leitzke A, Gheorghe CP, Longo LD. Brain renin-angiotensin system: fetal epigenetic programming by maternal protein restriction during pregnancy. Reprod Sci 2010; 17: 227 238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang U, Baker RS, Braems G, Zygmunt M, Kunzel W, Clark KE. Uterine blood flow–a determinant of fetal growth. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003; 110 (suppl 1): S55 S61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner CP, Thompson LP, Liu KZ, Herrig JE. Pregnancy reduces serotonin-induced contraction of guinea pig uterine and carotid arteries. Am J Physiol 1992; 263: H1764 H1769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahokas RA, Anderson GD, Lipshitz J. Cardiac output and uteroplacental blood flow in diet-restricted and diet-repleted pregnant rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1983; 146: 6 13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koumentaki A, Anthony F, Poston L, Wheeler T. Low-protein diet impairs vascular relaxation in virgin and pregnant rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002; 102: 553 560 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulgar VM, Yamashiro H, Rose JC, Moore LG. Role of the AT2 receptor in modulating the angiotensin II contractile response of the uterine artery at mid-gestation. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2011; 12: 176 183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan RE, Davis EA, Widdop RE. Functional role of angiotensin II AT2 receptor in modulation of AT1 receptor-mediated contraction in rat uterine artery: involvement of bradykinin and nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol 2003; 140: 987 995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangula PR, Reed L, Yallampalli C. Antihypertensive effects of flutamide in rats that are exposed to a low-protein diet in utero. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 952 960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong WY, Wild AE, Roberts P, Willis AC, Fleming TP. Maternal undernutrition during the preimplantation period of rat development causes blastocyst abnormalities and programming of postnatal hypertension. Development 2000; 127: 4195 4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Gardner DS, Jackson AA. Maternal protein restriction influences the programming of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Nutr 1996; 126: 1578 1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC. Sex-specific effects of prenatal low-protein and carbenoxolone exposure on renal angiotensin receptor expression in rats. Hypertension 2005; 46: 1374 1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC. Maternal low-protein diet in rat pregnancy programs blood pressure through sex-specific mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005; 288: R85 R90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins AJ, Wilkins A, Cunningham C, Perry VH, Seet MJ, Osmond C, Eckert JJ, Torrens C, Cagampang FR, Cleal J, Gray WP, Hanson MA, et al. Low protein diet fed exclusively during mouse oocyte maturation leads to behavioural and cardiovascular abnormalities in offspring. J Physiol 2008; 586: 2231 2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano E, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Guzman C, Garcia-Becerra R, Boeck L, Diaz L, Menjivar M, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. A maternal low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation in the rat impairs male reproductive development. J Physiol 2005; 563: 275 284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricks DM, Bailey LB. Effect of dietary protein restriction on hormone status and embryo survival in the pregnant rat. Biol Reprod 1976; 14: 143 150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulay S, Varma DR, Solomon S. Influence of protein deficiency in rats on hormonal status and cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors in maternal and fetal tissues. J Endocrinol 1982; 95: 49 58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armando I, Jezova M, Juorio AV, Terron JA, Falcon-Neri A, Semino-Mora C, Imboden H, Saavedra JM. Estrogen upregulates renal angiotensin II AT(2) receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2002; 283: F934 F943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiardi G, Macova M, Armando I, Ando H, Tyurmin D, Saavedra JM. Estrogen upregulates renal angiotensin II AT1 and AT2 receptors in the rat. Regul Pept 2005; 124: 7 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnihan KB, Hodgin JB, Smithies O, Maeda N, Gallagher P. Tissue-specific regulation of ACE/ACE2 and AT1/AT2 receptor gene expression by oestrogen in apolipoprotein E/oestrogen receptor-alpha knock-out mice. Exp Physiol 2008; 93: 658 664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisley LR, Sakai RR, Fluharty SJ. Estrogen decreases hypothalamic angiotensin II AT1 receptor binding and mRNA in the female rat. Brain Res 1999; 844: 34 42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer A, Pinto JE, Viglione PN, Correa FM, Libertun C, Tsutsumi K, Steele MK, Saavedra JM. Estrogens regulate angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin receptors in female rat anterior pituitary. Neuroendocrinology 1992; 55: 460 467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydrup ML, Ferno M. Correlation between estrogen receptor alpha expression, collagen content and stiffness in human uterine arteries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003; 82: 610 615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson C, Lydrup ML, Ferno M, Idvall I, Gustafsson J, Nilsson BO. Immunocytochemical demonstration of oestrogen receptor beta in blood vessels of the female rat. J Endocrinol 2001; 169: 241 247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiberman JR, Wiznitzer A, Glezerman M, Feldman B, Levy J, Sharoni Y. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in the uterine artery of rats during and after pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993; 51: 35 40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird IM, Zheng J, Cale JM, Magness RR. Pregnancy induces an increase in angiotensin II type-1 receptor expression in uterine but not systemic artery endothelium. Endocrinology 1997; 138: 490 498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell JH, Lumbers ER. Angiotensin receptor subtypes in the uterine artery during ovine pregnancy. Eur J Pharmacol 1997; 330: 257 267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross GR, Chauhan M, Gangula PR, Reed L, Thota C, Yallampalli C. Female sex steroids increase adrenomedullin-induced vasodilation by increasing the expression of adrenomedullin2 receptor components in rat mesenteric artery. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 389 396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala M, Gokina N, Osol G. Contribution of nonendothelial nitric oxide to altered rat uterine resistance artery serotonin reactivity during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187: 463 468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osol G, Mandala M. Maternal uterine vascular remodeling during pregnancy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009; 24: 58 71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yallampalli C, Kondapaka SB, Lanlua P, Wimalawansa SJ, Gangula PR. Female sex steroid hormones and pregnancy regulate receptors for calcitonin gene-related peptide in rat mesenteric arteries, but not in aorta. Biol Reprod 2004; 70: 1055 1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naden RP, Rosenfeld CR. Effect of angiotensin II on uterine and systemic vasculature in pregnant sheep. J Clin Invest 1981; 68: 468 474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PN. Broughton Pipkin F, Symonds EM. Platelet angiotensin II binding and plasma renin concentration, plasma renin substrate and plasma angiotensin II in human pregnancy. Clin Sci (Lond) 1990; 79: 403 408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Shao Y, Huang Y, Yao T, Lu LM. 17beta-estradiol inhibits angiotensin II-induced collagen synthesis of cultured rat cardiac fibroblasts via modulating angiotensin II receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 2007; 567: 186 192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves LA, Stovall K, Joyner J, Valdes G, Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Merrill DC, Brosnihan KB. ACE2 and ANG-(1–7) in the rat uterus during early and late gestation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294: R151 R161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T, Jank A, Heringer-Walther S, Horn LC, Stepan H. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor has impact on murine placentation. Placenta 2008; 29: 905 909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abadir PM, Carey RM, Siragy HM. Angiotensin AT2 receptors directly stimulate renal nitric oxide in bradykinin B2-receptor-null mice. Hypertension 2003; 42: 600 604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007; 292: C82 C97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Matsubara H, Urakami M, Inada M. Rat angiotensin II (type 1A) receptor mRNA regulation and subtype expression in myocardial growth and hypertrophy. Circ Res 1993; 73: 439 447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan RE, Gaspari TA, Davis EA, Widdop RE. Differential regulation by AT(1) and AT(2) receptors of angiotensin II-stimulated cyclic GMP production in rat uterine artery and aorta. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 141: 1024 1031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Louis J, Sicotte B, Bedard S, Brochu M. Blockade of angiotensin receptor subtypes in arcuate uterine artery of pregnant and postpartum rats. Hypertension 2001; 38: 1017 1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JA, Rupnow HL, Cale JM, Magness RR, Bird IM. Pregnancy and ovarian steroid regulation of angiotensin II type 1 and type 2 receptor expression in ovine uterine artery endothelium and vascular smooth muscle. Endothelium 2005; 12: 41 56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasamura H, Hein L, Krieger JE, Pratt RE, Kobilka BK, Dzau VJ. Cloning, characterization, and expression of two angiotensin receptor (AT-1) isoforms from the mouse genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992; 185: 253 259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Oliverio MI, Mannon PJ, Best CF, Maeda N, Smithies O, Coffman TM. Regulation of blood pressure by the type 1A angiotensin II receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995; 92: 3521 3525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Chen Y, Dirksen WP, Morris M, Periasamy M. AT1b receptor predominantly mediates contractions in major mouse blood vessels. Circ Res 2003; 93: 1089 1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Yallampalli U, Yallampalli C. Maternal protein restriction reduces expression of angiotensin I converting enzyme 2 in rat placental labyrinth zone in late pregnancy. Biol Reprod 2012; 86: 31, 1 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]