Abstract

At present there is considerable variability in the psychiatric evaluation and follow-up of patients in epilepsy surgery programs globally. There is a large body of research now demonstrating heightened risk for psychological disturbance in surgically remedial patients before and after surgery. This evidence provides a compelling case for the routine provision of psychiatric and psychological treatment to optimize the benefits of epilepsy surgery and patient outcomes. In a comprehensive model of care, presurgical psychiatric and psychosocial evaluation plays an integral role in shaping the team's understanding of surgical candidacy and the patient's capacity for informed consent. After surgery, efficacious treatment of psychiatric comorbidity increases the likelihood of seizure freedom as well as optimizes psychosocial functioning and quality of life. By contrast, failure to treat can allow psychiatric comorbidity to persist or psychological difficulties to develop as the patient adjusts to life after surgery.

Introduction

The increasing sophistication of diagnostic and neurosurgical techniques has markedly improved our ability to successfully localize and resect epileptogenic tissue in patients with surgically remediable seizure syndromes (1). Despite this, psychiatric comorbidities remain under-recognized and undertreated (2), leading to a call for the prioritization of their management in recent international consensus clinical practice statements (3). Using contemporary psychiatric nosology (i.e., Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition [DSM-IV] and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition [ICD-10], this review focuses on the three most commonly reported psychiatric comorbidities experienced by adults before and after epilepsy surgery that may arise in the peri-ictal or inter-ictal state, namely depression, anxiety, and psychosis. In so doing, it provides strong empirical support for a model of comprehensive care that includes the routine provision of psychiatric and psychological services to all patients before and after seizure surgery to ensure an optimal outcome.

Psychological Disturbance in Surgically Remedial Epilepsy

Depressive Disorders

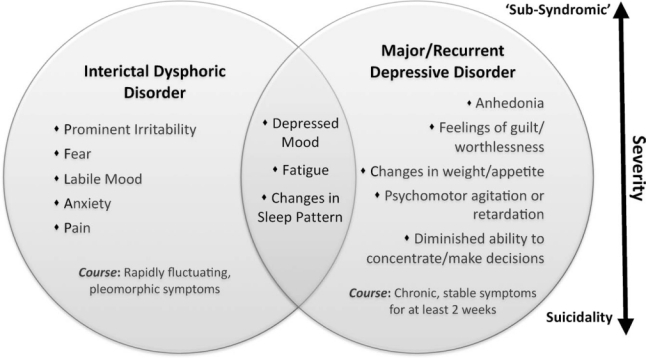

Depressed mood is the most prominent psychiatric symptom of epilepsy (4). Around 30 percent of people with refractory epilepsy experience clinically significant depressive symptoms in their lifetime (5), with 43 percent higher odds of developing depression than healthy controls (6). Major depression in epilepsy may be qualitatively different to that seen in the broader psychiatric population (7; see Figure 1). It requires assessment of whether depressive symptoms are temporally related to the ictal event, as inter-ictal and peri-ictal depressive disorders may respond differently to pharmacological treatment (3). Suicide is a chief cause of death among epilepsy patients, being up to 25 times more frequent than in the wider community (8). The recent international consensus statements recommend screening for depression on an annual basis, and given the increased risk of suicide promote active treatment rather than “watchful waiting,” even in patients with only mild depressive symptoms (3).

Figure 1.

Depressive disorders in epilepsy are considered to lie on a spectrum of severity ranging from low-grade ‘sub-syndromic’ depressive episodes to severe, suicidal depression. They may not always fit dominant category-based diagnostic systems such as DSM-IV-TR or ICD-10 (40,41), but can show overlapping features. Interictal Dysphoric Disorder is thought to be caused by paroxysmal, subthreshold hypersynchronous neural discharges that produce increasingly inhibitory responses in the mood network (7). The identification of IDD as a separate entity, however, has been clinically debated with further research needed to resolve the issue.

Both psychosocial and neurobiological mechanisms are thought to underpin depression in refractory epilepsy. Psychosocially, the challenges of living with habitual seizures are well-established and include physical restrictions, perceived and enacted stigma, low self-esteem, an inability to drive, reduced educational and vocational opportunities, disrupted family functioning, social isolation, and reduced quality of life (9–11). As children with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) transition into adulthood, a significant subset (48%) fail to master normative developmental tasks such as forming close interpersonal relationships, developing vocational direction, and obtaining financial independence. Lifespan approaches have also identified neurobiological factors associated with a heightened risk of depression, including illness chronicity (increased duration and frequency of seizures), nonlesional focal epilepsy, and the psychotropic effects of some antiepileptic drugs (11–13). Structural and functional neuroimaging findings have identified neural regions generally implicated in depression, such as inferior frontal and mesial temporal regions (14, 15), with ongoing epileptiform activity likely disrupting the integrity of the mood network bilaterally.

One particularly compelling hypothesis is that a shared pathophysiological mechanism accounts for both depression and seizures (16). This is driven by the empirical observation that a bidirectional relationship exists between seizures and depression, whereby patients with epilepsy are more likely to develop depression than people in the general population, and sufferers of major depression are at 4- to 7-times greater risk of experiencing an unprovoked seizure (17). Mechanisms thought to underlie the heightened comorbidity of mood disturbance and epilepsy include abnormal neurotransmitter functioning, aberrant inflammation by cytokines in response to epileptiform discharges, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, genetic aberrations, and abnormal neurogenesis in limbic structures such as the hippocampus (16).

Postsurgical depression

Prospective studies indicate that following surgery, around 30 percent of patients experience major depression (9, 18). Most depressive episodes are diagnosed in the first 3 months and persist for at least 6 months, with rates of depression steadily declining across a 24-month follow-up period. Moderate to severe levels of depressive symptoms can persist in about 15 percent of patients who continue to have postoperative seizures (19). Risk factors for depression after surgery include a preoperative history of affective disturbance and poor postoperative family dynamics (9). Surgical resections disrupting mesial temporal structures may place patients at increased risk of de novo depression after surgery (15, 18). In such patients, the onset of symptoms may be preceded by significant postoperative irritability and relationship conflict that may act as a catalyst for deteriorating mood. This supports the interaction of psychosocial and neurobiological antecedents of depression in epilepsy (9, 18).

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders comprise the second most prevalent psychiatric condition in epilepsy, occurring both peri-ictally and inter-ictally (4, 19). Because clinical research has focused on depression largely to the exclusion of anxiety, the risk factors and mechanisms underpinning anxiety remain ill-defined. Studies indicate that around 15 percent of patients with epilepsy meet criteria for one or more DSM-IV anxiety disorders (2), with a lifetime prevalence of 19 to 26 percent (19–21). Clinically, anxiety disorders in epilepsy are similar to those in the general population and commonly co-occur with depression, with a lifetime prevalence of mixed major depression/anxiety disorder reported as 34 percent compared with 19 percent in people without epilepsy (4). Comorbid anxiety/depressive disorders in epilepsy are associated with a poorer quality of life and worse response to treatment in each condition (2).

Variables that increase susceptibility to anxiety disorders in epilepsy include female gender, frequent seizures, and symptomatic focal epilepsies (22), with no clear relationship observed for the laterality or location of the seizure focus (19). Psychosocial factors have also been identified as independent determinants of anxiety, including stigma, insufficient information about seizures, and a sense of lack of control over seizure occurrence (11).

Postsurgical Anxiety

The clinical trajectory of anxiety after surgery typically shows a spike in anxious symptoms immediately following the procedure, with up to 40 percent of patients diagnosed with an anxiety disorder, including 32 percent with de novo symptomotology (21). Symptoms then steadily decline until baseline levels of anxiety are reached around 24 months postsurgery (19). There is also a trend for seizure-free patients to show a reduction in anxious symptoms (19). Patients at the highest risk of developing postoperative anxiety disorders are those with a past history of affective disorders, or TLE patients who typically experienced fear as a presurgical aura (16, 23). Neurobiologically, recent research has found that resection of an ipsilateral amygdala of normal volume is associated with postoperative anxiety in patients with mesial temporal resections, regardless of seizure outcome (21). This is broadly consistent with functional imaging data suggesting that greater preoperative ipsilateral amygdala activation in TLE patients with right foci is associated with significantly increased anxious symptomotology after surgery (24).

Psychosis

Although psychotic disorders are less common in people with epilepsy, they occur in around 7 percent of patients with refractory focal seizures (13), which is several times higher than the general population (25). Psychotic disorders may be temporally linked to the ictus, as in post-ictal psychosis, or they may show a more chronic and stable course that resembles schizophrenia (26). In general, the clinical presentation tends to be less severe and is characterized by an absence of negative symptoms, intact insight, and preserved personality, as well as a better response to pharmacotherapy than seen in schizophrenia (26). Factors associated with post-ictal psychosis include a history of psychiatric hospitalizations or family neuropsychiatric history, more frequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures than seen in patients without postictal psychois, bilateral interictal electroencephalographic activity, bilateral seizure foci, ambiguous seizure localization or a history of encephalitis, and clusters of seizures immediately preceding the psychotic episode (27–29). A number of studies have noted that poorly controlled TLE carries a heightened risk of psychosis (8), with structural imaging revealing widespread grey and white matter reduction in bilateral mesial temporal, lateral temporal, subcortical, and extratemporal structures that are akin to changes in patients with schizophrenia (30), as well as abnormalities in cortical thickness (31).

Postsurgical Psychosis

De novo psychosis after epilepsy surgery is rare, with around a 3 percent incidence following the most common procedure, anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL: 32). Clinicians working in epilepsy surgery programs often hold the belief that patients who achieve seizure relief after surgery also become free from post-ictal psychosis given the direct causal link between the two (26). Potential risk factors for developing de novo psychosis include a family history of psychosis, undergoing surgery aged 30 years and older, and epileptogenic pathology of cortical dysplasia or hamartoma (33, 34). The mechanisms for these vulnerability factors, however, remain unclear. In one study, a small subset of patients who developed de novo psychosis or aggravation of pre-existing psychoses showed dysfunctional personality traits before surgery (35), suggesting they may have developed psychotic disorders irrespective of epilepsy surgery (23).

Surgery: A Turning Point?

For many patients, epilepsy surgery can mark a critical juncture in their psychiatric trajectory. As noted above, for most patients it leads to improved mental health, but for some, it heralds an exacerbation or recurrence of a presurgical neurobehavioral condition, or the emergence of de novo symptoms. Early reports identified a 12–24 month lag between postoperative seizure relief and psychiatric improvements (1), during which time a transient deterioration in psychological well-being may occur. In approximately 60 percent of all ATL patients followed up at our seizure surgery follow-up and rehabilitation program, this takes the form of psychosocial adjustment difficulties, likened to being “burdened with normality” as patients face new challenges and refashion their psychosocial milieu while undergoing a transition from chronically ill to well (10, 32). Although the majority of patients master these challenges with the support of a seizure surgery follow-up and rehabilitation program, others remain psychiatrically unwell, with one study reporting ongoing use of psychotropic medication in up to 44 percent of patients at 24 months postsurgery (27).

To date, the majority of psychiatric outcome studies have focused on patient trajectories in the context of significant seizure improvement. What then becomes of the 30 percent of patients who experience seizure recurrence (36)? This question is especially pertinent to the management of psychiatrically vulnerable patients, as a lifetime history of psychiatric disturbance predicts worse seizure outcome after surgery (37). At this stage, significantly more research effort is needed to examine the psychological and social outcomes of patients with suboptimal medical outcomes to identify factors that promote resilience and protect against poor long-term outcomes (38).

Providing Comprehensive Surgical Care

At present there is considerable variability in the evaluation and follow-up of patients in epilepsy surgery programs. This poses a significant challenge to interpreting the results of outcome studies that has important implications for evidence-based clinical management (38). Ideally, comprehensive presurgical evaluation includes seizure diagnosis, neurophysiologic, neuroimaging, and neurocognitive investigations, psychiatric and psychosocial assessments, and routine counseling of the patient and family members. The latter should address expectations of surgical outcome, any identified neurobiologic or psychosocial risk factors and their prophylactic treatment, and the requirements of postoperative rehabilitation. Predicting individual patient outcomes after surgery remains a key challenge for clinicians, in particular identifying the interplay of factors that creates the greatest risk for each person (39). It requires a detailed understanding of the patient's suitability for surgery and optimal timing to maximize a range of outcomes, including medical, cognitive, psychiatric, and psychosocial functioning. In a comprehensive model of care, presurgical psychiatric evaluation plays an integral role in determining surgical candidacy, particularly in individuals with refractory seizures and comorbid psychotic episodes. Here, specialist neurobehavioral assessment is best used to determine the patient's ability to comply with treatment and to make an informed decision about elective surgery by weighing the risks against its potential therapeutic benefits (3). This assessment must canvass not only current psychopathology, but also previous episodes of psychiatric illness that are currently asymptomatic (2).

In line with presurgical evaluation, a comprehensive assessment of outcome should canvass a range of markers, including seizure, neurologic and cognitive outcomes, psychiatric and psychosocial functioning, and the patient's perceived quality of life. To achieve this, regular provision of medical and psychological follow-up is pertinent, particularly early after surgery. Compared with a traditional model of physical recovery after brain injury, rehabilitation after epilepsy surgery is often more psychosocially focused. Patients may require assistance with a change in their sense of self as they transition to a life without seizures that incorporates real benefits of seizure freedom. Moreover, any patient with both epilepsy and comor-bid psychopathology will often warrant both pharmacological and psychological interventions, with symptom remission achievable in up 60 percent of epilepsy patients treated with either pharmacotherapy or cognitive behavior therapy (39). In surgical patients, this, in turn, can increase the likelihood of achieving postoperative seizure freedom and maximizing psychosocial functioning and quality of life (3, 38).

Conclusions

This paper highlights the compelling body of research demonstrating that patients with surgically remediable epilepsy are vulnerable to neurobehavioral disturbance before and after surgery. It makes a strong case for obligatory psychiatric and psychosocial evaluation of every person being considered for epilepsy surgery, to provide the best chance of optimizing its benefits. The data reviewed here clearly highlight the need to routinely address all aspects of a surgical candidate's functioning so that current or potential psychiatric difficulties are flagged and treated. Although challenging to achieve, this comprehensive multidisciplinary approach provides a benchmark of best clinical practice for tertiary epilepsy centers. Failure to treat may allow pre-existing psychiatric conditions to worsen or increase the risk of adjustment difficulties and neurobehavioral disturbance postsurgery.

Highlights:

Patients with surgically remediable epilepsy are vulnerable to psychiatric disturbance before and after surgery.

A comprehensive model of surgical care includes routine psychiatric and psychosocial assessment so that current or potential difficulties may be flagged and treated.

Successful treatment of psychiatric comorbidity increases the likelihood of seizure freedom and optimizes the psychosocial benefits afforded by epilepsy surgery.

References

- 1.Wilson SJ, Engel J., Jr. Diverse perspectives on developments in epilepsy surgery. Seizure. 2010;19:659–668. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanner AM, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Hermann B, Meador KJ. Anxiety disorders, subsyndromic depressive episodes, and major depressive episodes: Do they differ on their impact on the quality of life of patients with epilepsy? Epilepsia. 2010;51:1152–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr MP, Mensah S, Besag F, de Toffol B, Ettinger A, Kanemoto K, Kanner A, Kemp S, Krishnamoorthy E, LaFrance WC, Mula M, Schmitz B, Tebartz van Elst L, Trollor J, Wilson SJ. International consensus clinical practice statements for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions associated with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52:2133–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tellez-Zenteno JF, Patten SB, Jette N, Williams J, Wiebe S. Psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy: A population-based analysis. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2336–2344. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Bell B. Psychiatric comorbidity in chronic epilepsy: Identification, consequences, and treatment of major depression. Epilepsia. 2000;4:S31–S41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller-Thomson E, Brennenstuhl S. The association between depression and epilepsy in a nationally representative sample. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1051–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blumer D, Montouris G, Davies K. The interictal dysphoric disorder: Recognition, pathogenesis, and treatment of the major psychiatric disorder of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;6:826–840. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaitatzis A, Trimble MR, Sander JW. The psychiatric comorbidity of epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;110:207–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2004.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrench JM, Rayner G, Wilson SJ. Profiling the evolution of depression after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2011;52:900–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson SJ, Bladin PF, Saling MM. The ‘burden of normality’: Concepts of adjustment after seizure surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2001;70:649–656. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.5.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacoby A, Baker GA, Steen N, Potts P, Chadwick DW. The clinical course of epilepsy and its psychosocial correlates: Findings from a U.K. community study. Epilepsia. 1996;37:148–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ettinger AB. Psychotropic effects of antiepileptic drugs. Neurology. 2006;67:1916–1925. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247045.85646.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams SJ, O'Brien TJ, Lloyd J, Kilpatrick CJ, Salzberg MR, Velakoulis D. Neuropsychiatric morbidity in focal epilepsy. Br J Psychiatr. 2008;192:464–469. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bromfield EB, Altshuler L, Leiderman DB, Balish M, Ketter TA, Devinsky O, Post RM, Theodore WH. Cerebral metabolism and depression in patients with complex partial seizures. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:617–623. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530300049010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wrench JM, Wilson SJ, Bladin PF, MD, Reutens DC. Hippocampal volume and major depression: insights from epilepsy surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2009;80:539–544. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.152165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salzberg M. Neurobiological links between epilepsy and mood disorders. Neurol Asia. 2011;16:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanner AM. Depression and epilepsy: A bidirectional relation? Epilepsia. 2011;52:21–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wrench JM, Wilson SJ, O'Shea MF, Reutens DC. Characterising de novo depression after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Res. 2009;83:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, Berg AT, Bazil CW, Pacia SV, Langfitt JT, Walczak TS, Sperling MR, Shinnar S, Spencer SS. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65:1744–1749. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt C, Schoendienst M, Trentowska M, May TW, Pohlmann-Eden B, Tuschen-Caffier B, Schrecke M, Fueratsch N, Witte-Boelt K, Ebner A. Prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with refractory focal epilepsy—A prospective clinic based survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;17:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halley SA, Wrench JM, Reutens DC, Wilson SJ. The amygdala and anxiety after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;18:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimiskidis VK, Triantafyllou NI, Kararizou E, Gatzonis S, Fountoulakis KN, Siatouni A, Loucaidis P, Pseftogianni D, Vlaikidis N, Kaprinis GS. Depression and anxiety in epilepsy: The association with demographic and seizure-related variables. Ann Gen Psychiatr. 2007;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foong J, Flugel D. Psychiatric outcome of surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy and presurgical considerations. Epilepsy Res. 2007;75:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonelli SB, Powell R, Yogarajah M, Thompson PJ, Symms MR, Koepp MJ, Duncan JS. Preoperative amygdala fMRI in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50:217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1996;53:1022–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanner AM. Psychosis of epilepsy: A neurologist's perspective. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1:219–227. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanner AM. Does a history of postictal psychosis predict a poor postsurgical seizure outcome? Epilepsy Curr. 2009;9:96–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2009.01304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alper K, Devinsky O, Westbrook L, Luciano D, Pacia S, Perrine P, Vazquez B. Premorbid psychiatric risk factors for postictal psychosis. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2001;13:492–499. doi: 10.1176/jnp.13.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Devinsky O, Abramson H, Alper K, Savino-Fitzgerald L, Perrine K, Calderon J, Luciano D. Postictal psychosis: A case control series of 20 patients and 150 controls. Epilepsy Res. 1995;20:247–253. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(94)00085-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundram F, Cannon M, Doherty CP, Barker GJ, Fitzsimons M, Delanty N, Cotter D. Neuroanatomical correlates of psychosis in temporal lobe epilepsy: Voxel-based morphometry study. Br J Psychiatr. 2010;197:482–492. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubois JM, Devinsky O, Carlson C, Kuzniecky R, Quinn BT, Alper K, Butler T, Starner K, Halgren E, Thesen T. Abnormalities of cortical thickness in postictal psychosis. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;21:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bladin PF. Psychosocial difficulties and outcome after temporal lobectomy. Epilepsia. 1992;33:898–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1992.tb02198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, O'Connor MJ, Sperling MR. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:53–58. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor DC. Factors influencing the occurrence of schizophrenia-like psychosis in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Psychol Med. 1975;5:249–254. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700056609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoue Y, Mihara T. Psychiatric disorders before and after surgery for epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2001;42:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McIntosh AM, Wilson SJ, Berkovic SF. Seizure outcome after temporal lobectomy: Current research practice and findings. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1288–1307. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanner AM, Byrne R, Chicharro A, Wuu J, Frey M. A lifetime psychiatric history predicts a worse seizure outcome following temporal lobectomy. Neurology. 2009;72:793–799. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343850.85763.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirbin CA, McIntosh AM, Wilson SJ. The experience of seizures after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;16:82–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wrench JM, Matsumoto R, Inoue Y, Wilson SJ. Current challenges in the practice of epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilliam FG, Black KJ, Vahle V, Randall A, Sheline Y, Wei-Yann T, Lustman P. Depression and health outcomes in epilepsy: A randomized trial (Abstract) Neurology. 2009;72:A261. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]