Abstract

A highly conserved, Hsp70-based, import motor, which is associated with the translocase on the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane, is critical for protein translocation into the matrix. Hsp70 is tethered to the translocon via interaction with Tim44. Pam18, the J-protein co-chaperone, and Pam16, a structurally related protein with which Pam18 forms a heterodimer, are also critical components of the motor. Their N termini are important for the heterodimer’s translocon association, with Pam18’s and Pam16’s N termini interacting in the intermembrane space and the matrix, respectively. Here, using the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae, we report the identification of an N-terminal segment of Tim44, important for association of Pam16 with the translocon. We also report that higher amounts of Pam17, a nonessential motor component, are found associated with the translocon in both PAM16 and TIM44 mutants that affect their interaction with one another. These TIM44 and PAM16 mutations are also synthetically lethal with a deletion of PAM17. In contrast, a deletion of PAM17 has little, or no genetic interaction with a PAM18 mutation that affects translocon association of the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer, suggesting a second role for the Pam16:Tim44 interaction. A similar pattern of genetic interactions and enhanced Pam17 translocon association was observed in the absence of the C terminus of Tim17, a core component of the translocon. We suggest the Pam16:Tim44 interaction may play two roles: (1) tethering the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer to the translocon and (2) positioning the import motor for efficient engagement with the translocating polypeptide along with Tim17 and Pam17.

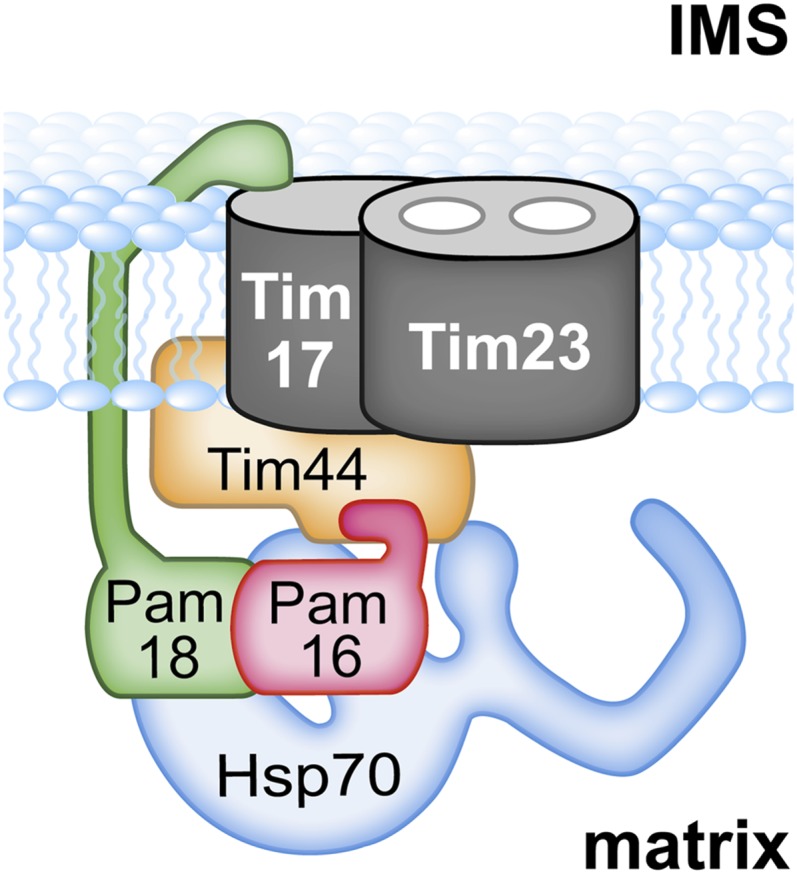

SINCE the vast majority of proteins of the mitochondrial matrix are synthesized on cytosolic ribosomes, the process of translocation across the outer and inner membranes must be efficient to maintain properly functioning mitochondria. These proteins, typically synthesized with a positively charged N-terminal targeting presequence, are first recognized by receptors on the outer membrane and then transferred sequentially through proteinaceous channels in the outer and inner membranes, the TOM and TIM23 complexes, respectively (Endo and Yamano 2009; Schmidt et al. 2010). The insertion of the N-terminal presequence into the TIM23 complex is strictly dependent on a membrane potential across the inner membrane. However, translocation of the remainder of the protein requires the action of the presequence translocase-associated motor complex (PAM), which resides on the matrix side of the inner membrane (Van Der Laan et al. 2010; Marom et al. 2011) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

Overview of import motor. Integral membrane proteins Tim23 and Tim17 form the trans-locon for translocating polypeptides across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the matrix. Pam16 and Pam18 interact via J-type domains. This heterodimer is tethered to the translocon by two interactions: Pam18’s N terminus with Tim17 in the intermembrane space (IMS) and, as discussed here, an interaction of Pam16, likely with the extreme N terminus of Tim44; Hsp70 is also tethered to the translocon via interaction with Tim44. Pam17, an integral membrane protein is not depicted because its site(s) of interaction with the translocon or other motor components is not understood.

The core of the TIM23 translocon is composed of two related, essential transmembrane proteins, Tim23 and Tim17, both of which have four membrane-spanning domains, as well as N-terminal and C-terminal segments that are exposed to the intermembrane space (IMS). Tim23 is thought to form the channel through which the translocating polypeptide passes, while evidence suggests that Tim17 may regulate the channel (Bauer et al. 1996; Ryan et al. 1998; Truscott et al. 2001; Meier et al. 2005; Martinez-Caballero et al. 2007). PAM is an Hsp70-based import motor, which couples the polypeptide binding activity of Hsp70 to the movement of the polypeptide through the channel. PAM contains four essential components, Tim44, Pam16 (also called Tim16), Pam18 (also called Tim14), and Mge1, in addition to Hsp70 (called Ssc1 in yeast). Like all Hsp70s (Mayer and Bukau 2005; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl 2009), Ssc1 binds exposed hydrophobic stretches of its client protein, the translocating polypeptide, in its ATP-bound state, with the interaction being stabilized by the hydrolysis of ATP. Efficient hydrolysis requires a partner J protein, and release of the client protein requires the action of a nucleotide exchange factor (Kampinga and Craig 2010). In PAM, these functions are carried out by the J domain of the J protein Pam18 (D’Silva et al. 2003; Mokranjac et al. 2003; Truscott et al. 2003) and the nucleotide exchange factor Mge1 (Deloche and Georgopoulos 1996; Miao et al. 1997), respectively.

While Mge1 is a soluble protein that interacts directly with Ssc1, both Ssc1 and Pam18 are tethered to the translocon (Figure 1). The results of both in vivo and in vitro experiments indicate that Ssc1 interacts directly with Tim44 (Rassow et al. 1994; Schneider et al. 1994; Liu et al. 2003). In particular, a fragment of Tim44 extending from amino acid 43, the N terminus of the mature protein, to amino acid 209 interacts with Ssc1 in vitro, with residues between 174 and 209 implicated in regulating the interaction (Merlin et al. 1999; Schiller et al. 2008). The association of Pam18 with the translocon is multifaceted. It is a transmembrane protein with a single membrane-spanning region. The N terminus is in the IMS; the C-terminal J domain, which is critical for stimulation of Ssc1’s ATPase activity, is in the matrix. The IMS domain interacts with Tim17 and helps stabilize Pam18’s association with the translocon (Chacinska et al. 2005; D’Silva et al. 2008). However, this interaction between Pam18’s IMS domain and Tim17 is not the primary mode of tethering Pam18 to the translocon. Pam18 forms a heterodimer with Pam16, which in turn interacts with the translocon (Frazier et al. 2004; Kozany et al. 2004; D’Silva et al. 2005). Genetic and cell biological evidence indicates that this interaction of Pam16 with the translocon is the more important of the two interactions for Pam18’s localization, with the Pam18 IMS:Tim17 interaction playing a secondary role (Mokranjac et al. 2007; D’Silva et al. 2008).

Pam16 has sequence and structural similarities with Pam18, with its C terminus being similar to Pam18’s J domain. It is via these J-type domains that the two proteins interact (Li et al. 2004; D’Silva et al. 2005; Mokranjac et al. 2006). The N-terminal region of Pam16 is important for its association with the translocon (Mokranjac et al. 2007; D’Silva et al. 2008). Tim44 has been implicated as Pam16’s interaction partner through genetic and crosslinking experiments (Kozany et al. 2004; Mokranjac et al. 2007; D’Silva et al. 2008; Hutu et al. 2008). Particularly relevant to this report, amino acid alterations in Tim44 (residues 79, 80, and 83) cause partial suppression of the phenotypic effects caused by alterations of amino acids in the N-terminal domain of Pam16 important for Pam16’s interaction with the translocon (D’Silva et al. 2008). In addition to these essential motor components, a nonessential protein called Pam17 is also part of the import motor (Van Der Laan et al. 2005). Mitochondria isolated from pam17-Δ cells are defective in protein import (Van Der Laan et al. 2005; Hutu et al. 2008; Schiller 2009).

As previously published work indicates (Frazier et al. 2004; Kozany et al. 2004; Chacinska et al. 2005; D’Silva et al. 2005, 2008), the translocation motor is a complex and dynamic system. Although most of the components of the translocon and the motor are essential, the complexities and functional redundancies within the system have become apparent as work has progressed toward defining specific interactions. To better understand the role of Tim44 and Pam17 in both the association of the Pam16/18 complex with the translocon and its regulation, we have carried out a more detailed genetic analysis, particularly analyzing genetic interactions between mutations that alone have little phenotypic effect. In this way, we have uncovered a critical region in the N terminus of Tim44 important for Pam16’s interaction with the translocon. In addition, we observed additional genetic interactions that suggest a function of the Tim44:Pam16 interaction, in addition to simple tethering, which involves Pam17 and the C terminus of Tim17.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains, plasmids, and genetic techniques

The genes for TIM44, PAM18, PAM16, and PAM17 were deleted in the W303 yeast strain background as previously described (Maarse et al. 1992; D’Silva et al. 2003, 2005; Schiller 2009). To create double deletion strains, the single deletion haploids were mated and the resulting diploids were transformed with the desired plasmids, sporulated and dissected. Screening for the correct deletion and plasmid marker genes identified the desired haploids. The gene for TIM17 was PCR amplified using chromosomal DNA from position –342 to +725 with Pfu Turbo polymerase (Stratagene) and cloned into the pRS series of plasmids (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). To create a deletion of TIM17, the complete ORF was replaced with the HIS3 gene using PCR and transformed into PJ53 (James et al. 1996). The heterozygous TIM17/tim17::HIS3 diploid was transformed with pRS316-TIM17, sporulated, and tim17-Δ haploids carrying pRS316-TIM17 were isolated by dissecting tetrads.

PAM18 mutants, L150W and ΔIMS, which lack the 60-amino-acid N-terminal domain localized in the IMS, were made as described previously (D’Silva et al. 2005, 2008). TIM44 mutants, Δ68-82, Δ82-99, and Δ103-118, were made as described previously (Schiller et al. 2008). The PAM16 N-terminal truncation mutations were made by PCR sewing the codons for the 69-amino-acid presequence from subunit 9 of the F1F0 ATPase to PAM16 starting at either codon 13 or codon 28, using Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) and cloning into pRS315 under control of the PAM16 promoter. All site-directed point mutations and deletions made in this study were constructed using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene).

To obtain temperature sensitive (TS) mutations in either TIM44 or PAM17, plasmid libraries containing randomly mutagenized DNA through PCR amplification were generated. For TIM44, an AatII–AgeI (+24 to +339) fragment was amplified and used to replace the same fragment in pRS314-TIM44. For PAM17, the entire gene was amplified (−412 to +925) and cloned into pRS313. tim44-Δ pam17-Δ cells carrying pRS316-TIM44 were transformed with the pRS314-tim44 library and incubated at 30° on tryptophan omission (Trp−) plates. Transformants were patched onto 5-fluoro-orotic acid (5-FOA) (Toronto Research Chemicals) plates and Trp− plates and incubated at 37° to identify those cells that could not grow at 37° in the absence of the wild-type (wt) copy of Tim44. pRS314-tim44 plasmids were recovered from those cells that could not grow at 37° on the 5-FOA plates. They were used to transform the parent strain to verify the TS phenotype. Correct candidates were sequenced at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology facility to identify the mutation. Using a similar procedure, pam17-Δ tim44-Δ cells carrying pRS314-tim44F54S and pRS316-PAM17 were transformed with the pRS313-pam17 library and incubated at 23° on histidine omission (His−) plates. Transformants were patched onto 5-FOA and His− plates and incubated at 34°. pRS313-pam17 plasmids were recovered from transformants that could not grow at 34° on 5-FOA plates. Plasmids that retested correctly were sequenced.

Co-immunoprecipitiation from mitochondrial lysates

As previously described (D’Silva et al. 2008), association of Pam16, -17, -18, and Tim44 with the Tim23 translocon was determined by co-immunoprecipitation. To insure low background, antibodies against Tim23 were affinity purified prior to cross-linking to protein A sepharose beads (D’Silva et al. 2005). Mitochondria were solubilized at 1 mg/ml in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM PMSF) containing 1% digitonin (Acros Organics) on ice for 40 min with gentle mixing (Mokranjac et al. 2003). After spinning at 20,800 × g at 4° for 15 min, the lysates were added to 20 µl (bed volume) of Tim23 antibody beads and incubated 2 hr with mixing at 4°. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer containing 0.1% digitonin before boiling in sample buffer. The proteins were separated on SDS–PAGE and detected by immunoblotting.

Protein purification and antibodies

The coding region for Pam17 mature protein (+112 to +591) was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA and cloned into pET21d (Novagen), a plasmid that supplies codons for a six-histidine C-terminal tag for purification from Escherichia coli. A C41 E. coli strain transformed with pET21d-PAM17 was grown in 500 ml of LB at 30° until OD600 of 0.7 at which time 0.5 mM IPTG was added and growth continued for 6 hr. Cells were lysed in 1× PBS containing 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol by French press. The cleared lysate was incubated with 1 ml of Ni-NTA resin, washed extensively with lysis buffer, and eluted with 500 mM imidizole in lysis buffer.

Immunoblot analysis was carried out using standard techniques with protein detection by enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare). We used polyclonal antibodies to Tim23 (D’Silva et al. 2008), Tim44 (Liu et al. 2001), Pam16 (D’Silva et al. 2005), Pam18 (D’Silva et al. 2003), Mdj1 (Voisine et al. 2001), Hsp60, and Tim17 (gift from Nikolaus Pfanner). Polyclonal antibody to Pam17 was made in rabbits by Harlan Bioproducts using purified full-length Pam17.

Miscellaneous

Pam17 orthologous proteins were identified by basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) searches (Altschul et al. 1990, 1997), using protein sequences of S. cerevisiae Pam17 as a query. Results from each BLAST search that were statistically significant were then used as query sequences in the BLAST search against the S. cerevisiae protein database to identify reciprocal-best-blast sequences as orthologs. Sequences were aligned using the ClustalW program (Thompson et al. 1994), followed by manual inspection.

Secondary structure predictions for Tim44 were carried out using the following programs: PROFsec (Rost 2001), PSSpred (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/PSSpred), and SSpro (Pollastri et al. 2002).

Mitochondria were purified from cells grown at 30° in YPgly (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, and 3% glycerol) according to a previously described protocol (Liu et al. 2001). Whole-cell lysates were generated by resuspending a 1 OD600 cell pellet in 100 µl of 2× SB and adding ∼10 µl of glass beads. After vortexing the cell suspension for 2 min at 4°, the mixture was boiled for 5 min and then centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000 rpm to clear the lysate. All chemicals, unless noted otherwise, came from Sigma.

Results

N terminus of Tim44 is important for association of Pam16 with the translocon

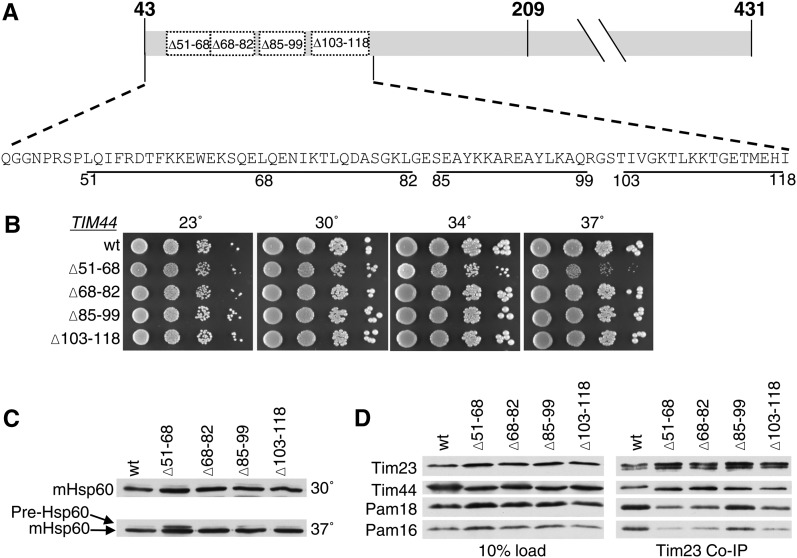

To better understand the functional interaction between the import motor and the translocon, we first sought to identify a region of Tim44 important for interaction with Pam16. On the basis of the location of previously identified mutations in TIM44 that partially suppressed the deleterious effect of mutations in PAM16 affecting translocon association (D’Silva et al. 2008), we concentrated on the N-terminal 75 amino acids of the mature form of Tim44, amino acids 43–118. As a first step, we tested the effect of three existing small internal deletions, tim44Δ68-82, tim44Δ85-99, and tim44Δ103-118 (Figure 2A). Consistent with our previous report (Schiller et al. 2008), these deletions had either no, or a very mild effect on growth (Figure 2B). We also constructed a fourth mutant, deleting codons for residues 51–68. tim44Δ51-68 grew more poorly than wt at all temperatures tested, but particularly so at 37° (Figure 2B).

Figure 2 .

N terminus of Tim44 is important for Pam16/18 association with the translocon. (A) Diagram of mature Tim44 (residues 43–431) showing the internal deletion variants marked with the numbers of the endpoint residues. (B) Growth phenotype. Tenfold serial dilutions of tim44-Δ cells carrying pRS314 expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (C) Precursor accumulation. Whole-cell lysates of the indicated TIM44 mutants were prepared from cells grown in rich media to an OD600 of 0.8–1.2 at either 30° or 37°. Proteins separated by SDS–PAGE were subjected to immunoblot analysis by using antibodies specific to Hsp60. The precursor form (pre-Hsp60) and mature (mHsp60) form of Hsp60 are indicated. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation with Tim23. Equivalent amounts of purified mitochondria from the indicated TIM44 mutant strains were solubilized in buffer containing 1% digitonin. The cleared supernatants were incubated with protein A beads cross-linked to Tim23-specific antibody. The samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Tim23-, Tim44-, Pam18-, and Pam16-specific antibodies. Ten percent of total soluble material after lysis was used as a loading control (10% load).

Many mitochondrial proteins contain an N-terminal targeting presequence that is cleaved after translocation into the mitochondrial matrix. Thus, an in vivo defect in mitochondrial import can be detected by monitoring the accumulation of the precursor form of a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein. To assess whether any of these four TIM44 deletions displayed obvious defects in mitochondrial import, the accumulation of the precursor form of Hsp60 was monitored using immunoblot analysis in each of the strains described above (Figure 2C). Precursor accumulation was observed in tim44Δ51-68 at 37°, but not the other three deletion mutants (Figure 2C), consistent with the growth defects observed.

To test whether these alterations in Tim44 affect the interaction of the Pam16/18 heterodimer with the translocon, we carried out co-immunoprecipitation experiments, using antibodies specific for Tim23 and mitochondria isolated from cells grown at 30°. Mitochondrial lysates were generated by treatment with digitonin, which disrupts the inner membrane, but preserves interactions between the PAM components and the translocon (Mokranjac et al. 2003; D’Silva et al. 2008). Co-immunoprecipitation of Tim44, Pam18, and Pam16 was assessed by immunoblot analysis. The Tim44 variants were co-immunopreciptated with the translocon at least as efficiently as wt. However, this was not the case with Pam16 and Pam18. Most relevant to this report, coprecipitation of Pam16 and Pam18 was much less efficient from lysates of mitochondria isolated from tim44Δ51-68 (Figure 2D), which, of the four deletion mutants, had the most severe growth defect and accumulates the precursor form of Hsp60.

Genetic interaction analysis provides evidence for Tim44 residues 51–82 being an interaction site for the N terminus of Pam16

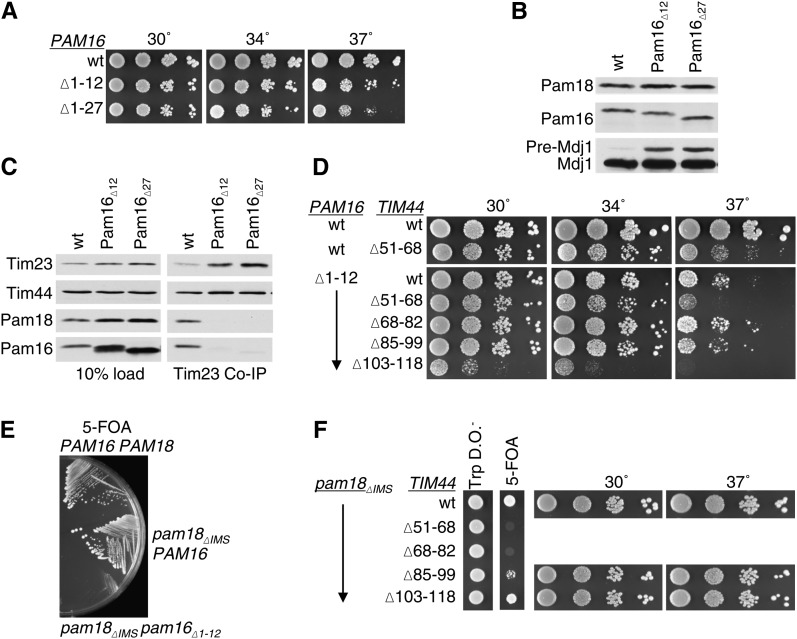

The results described above implicate the N terminus of Tim44 as being important for interaction with Pam16. If so, combining mutations in TIM44 and PAM16 that eliminate these proteins’ interaction sites would be expected to have little synthetic effect, as each mutation, individually, severely compromises the interaction. To test this idea, we first characterized in our system two PAM16 mutants, pam16Δ1-12 and pam16Δ1-27, which lack the codons for the N-terminal 12 and 27 residues, respectively. Both pam16Δ1-12 and pam16Δ1-27 were supplied with the codons for the 69-amino-acid mitochondrial presequence from subunit 9 of the F1F0-ATPase to target them to mitochondria. pam16-Δ cells carrying either of these mutant genes on a plasmid were temperature sensitive for growth at 37°, but grew only slightly more slowly than wt cells at lower temperatures (Figure 3A). Precursor accumulation of the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein Mdj1 was assessed in extracts prepared from these mutant cells grown at 30°. Strains carrying either truncation mutant accumulated Mdj1 precursor, indicating an in vivo defect in translocation of proteins into the matrix (Figure 3B). In addition, mitochondrial lysates were prepared as described above and subjected to co-immunoprecipitation analysis using Tim23-specific antibodies. Consistent with previous results (Mokranjac et al. 2007), the amount of Pam16 and Pam18 co-immunoprecipitated from mutant lysates was greatly reduced compared to that from wt extracts, although the amounts of Tim44 precipitated from the three extracts were similar (Figure 3C). Thus, the interaction between Pam16 and the translocon was severely affected in the absence of the N terminus of Pam16.

Figure 3 .

Lack of genetic interaction of PAM16 and TIM44 mutations affecting the extreme N termini of the two proteins. (A) Growth phenotype. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam16-Δ cells carrying pRS315 expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (B) Precursor accumulation. Whole-cell lysates of the indicated PAM16 mutants were prepared from cells grown in rich media to OD600 of 0.8–1.2 at 30°. Proteins separated by SDS–PAGE were subjected to immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific to Mdj1. The precursor form (pre-Mdj1) and mature (Mdj1) form of Hsp60 are indicated. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation with Tim23. Equivalent amounts of purified mitochondria from the indicated PAM16 mutant strains were solubilized in buffer containing 1% digitonin. The cleared supernatants were incubated with protein A beads cross-linked to Tim23-specific antibody. The samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Tim23-, Tim44-, Pam18-, and Pam16-specific antibodies. Ten percent of total soluble material after lysis was used as a loading control (10% load). (D) Growth phenotype. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam16-Δ tim44-Δ double deletion strains carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated for 3 days at the indicated temperatures. Spaces represent separate plates dropped at the same time. (E) Synthetic lethality of strain expressing both Pam16 lacking N-terminal residues and Pam18 lacking its IMS domain. pam16-Δ pam18-Δ strains carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were streaked onto 5-FOA plates and incubated for 5 days at 23°. (F) Synthetic interactions. pam18-Δ tim44-Δ strains, carrying PAM18 on a URA3-marked plasmid along with pam18ΔIMS on pRS315 and the indicated tim44 deletion mutants on pRS314, were dropped on tryptophan drop out plates (TRP DO) and 5-FOA plates and incubated for 4 days at 23°. Viable strains from the 5-FOA plate were serially diluted, plated on rich media, and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. Spaces represent cropping of picture taken of the same plates.

Next we constructed strains carrying combinations of pam16Δ1-12 and each of the four TIM44 mutations, tim44Δ51-68, tim44Δ68-82, tim44Δ85-99, and tim44Δ103-118. To obtain the desired strains, we first constructed a set of pam16-Δ tim44-Δ haploids. These initial haploids carried two plasmids, one containing a wt PAM16 gene on a URA3-marked plasmid and the second carrying one of the TIM44 mutants to be tested or, as a control, a wt TIM44 gene, on a TRP1-marked plasmid. Each haploid was then transformed with a plasmid carrying either wt PAM16 or pam16Δ1-12 on a LEU2-marked plasmid. Cells that had lost the wt copy of PAM16 were selected for on 5-FOA plates, as 5-FOA is toxic to cells having a functional uracil biosynthetic pathway, but not to cells lacking a functional URA3 gene (see Materials and Methods). 5-FOA–resistant colonies were recovered in all cases. The three deletion mutants removing codons encoding the most N-terminal residues, tim44Δ51-68, tim44Δ68-82, and tim44Δ85-99, showed little, or no, negative genetic interaction with the PAM16 mutation (Figure 3D, Table 1). On the other hand, tim44Δ103-118, which showed no obvious growth defect when in an otherwise wt background showed a severe genetic interaction with pam16Δ1-12. tim44Δ103-118pam16Δ1-12 was viable, but did not grow at 37° and grew very slowly at lower temperatures (Figure 3D, Table 1). That tim44Δ51-68, even though it grows more slowly than wt at 37° in a wt PAM16 background, showed no obvious genetic interaction with a mutation in PAM16 that removes sequences important for translocon association, is consistent with residues 51–68 of Tim44 being involved in the interaction of Pam16 with the translocon.

Table 1 . Strength of genetic interactions.

| Allele | pam18ΔIMS | pam16Δ1-12 | pam17-Δ | tim17ΔC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tim44Δ51-68 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| tim44Δ68-82 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| tim44Δ85-99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| tim44Δ103-118 | 0 | 3/4 | 0 | 0 |

| pam18ΔIMS | — | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| pam16Δ1-12 | 4 | — | 4 | 4 |

| pam17-Δ | 0 | 4 | — | 4 |

| tim17ΔC | 0 | 4 | 4 | — |

0, none/very mild; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, strong; and 4, very strong/lethal.

To further genetically test the idea that the N-terminal residues of Tim44, particularly in the interval between residues 51 and 82, are important for association of the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer with the translocon, we carried out an additional synthetic interaction experiment. We used a PAM18 mutant, pam18ΔIMS, which encodes a variant lacking the N-terminal 60 amino acids important for providing a second interaction site to the translocon (Chacinska et al. 2005; Mokranjac et al. 2007; D’Silva et al. 2008). First, as a control, we tested the genetic interaction between pam18ΔIMS and pam16Δ1-12, using a genetic procedure similar to that described above. However, we were unable to recover pam18ΔIMSpam16Δ1-12 colonies on 5-FOA plates (Figure 3E, Table 1), indicating that these two mutations are synthetically lethal. Upon elimination of both interaction sites, Pam16 with Tim44 and Pam18 with Tim17, cells are unable to grow, suggesting that the import motor is unable to translocate proteins at a level required for viability. Next we tested pam18ΔIMS in combination with the TIM44 N-terminal deletions. tim44Δ85-99 and tim44Δ103-118 had no obvious genetic interaction. However, tim44Δ51-68 and tim44Δ68-82 were synthetically lethal with pam18ΔIMS, as was pam16Δ1-12. (Figure 3F, Table 1). These data are consistent with previous results demonstrating a bipartite interaction of the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer with the translocon (Figure 1). In addition, they are consistent with the involvement of the N terminus of mature Tim44, that is, residues in the interval of 51–82, in the interaction with Pam16 and thus the tethering of both Pam16 and Pam18 to the translocon.

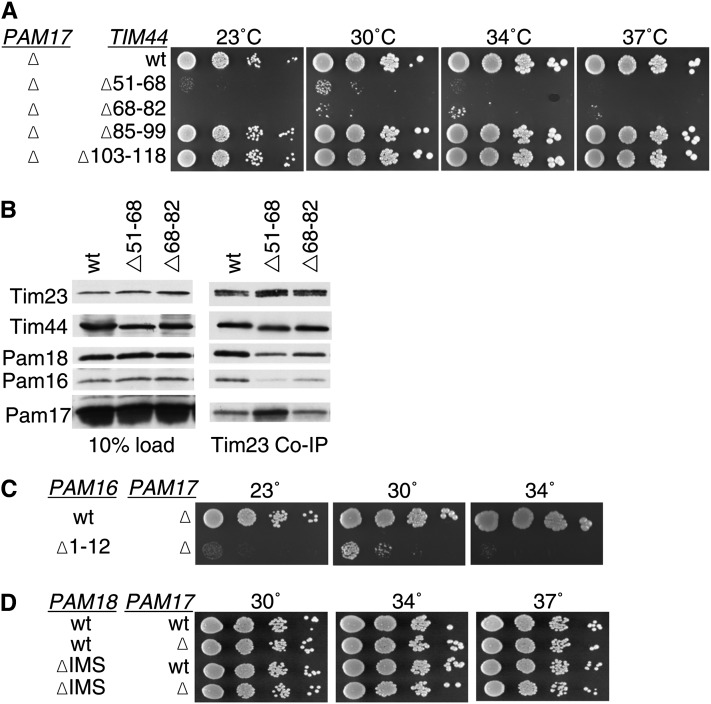

Severe genetic interactions between PAM17 deletion and N-terminal TIM44 mutations

The results described above are consistent with the N terminus of Tim44 being a site of interaction for Pam16 with the translocon. Because previous results suggested that Pam17 may also affect association of the import motor with the translocon (Van Der Laan et al. 2005; Hutu et al. 2008), we proceeded to test genetic interactions between the TIM44 deletions described above and a deletion of PAM17. In an otherwise wt background, the lack of Pam17 had no obvious effect on growth, regardless of temperature, under typical laboratory conditions. However, tim44Δ51-68 and tim44Δ68-82pam17-Δ double mutants were barely viable, growing extremely slowly at all temperatures tested (Figure 4A, Table 1). On the other hand, tim44Δ85-99 and tim44Δ103-118 showed no negative genetic interaction with pam17-Δ. Thus, the TIM44 internal deletions that were synthetic lethal with pam18ΔIMS, tim44Δ51-68, and tim44Δ68-82, also had severe genetic interactions with the PAM17 deletion. Because of these severe genetic interactions, we assessed the effect of these TIM44 deletions on the association of Pam17 with the translocon using co-immunoprecipitation. Consistent with previously published results (Popov-Celeketic et al. 2008), the percentage of Pam17 coprecipitated using Tim23-specific antibodies was significantly less than that of Tim44, Pam18, or Pam16. However, the amount of Pam17 coprecipitated with Tim23 was severalfold higher from tim44Δ51-68 than from wt lysates (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 .

Pam17 is essential when the Pam16:Tim44 interaction is compromised. (A) Growth phenotype. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam17-Δ tim44-Δ cells expressing the indicated Tim44 variants were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation with Tim23. Equivalent amounts of purified mitochondria from the indicated Tim44 mutant strains were solubilized in buffer containing 1% digitonin. The cleared supernatants were incubated with protein A beads cross-linked to Tim23-specific antibody. The samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Tim23-, Tim44-, Pam18-, Pam16-, and Pam17-specific antibodies. Ten percent of total soluble material after lysis was used as a loading control (10% load). (C and D) Growth phenotypes. Tenfold serial dilutions of either pam17-Δ pam16-Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing the indicated Pam16 protein or pam18-Δ pam17-Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days.

Since the results presented above suggest that the interval between residues 51 and 82 of Tim44 is important for association of the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer with the translocon and deletions within this region have severe genetic interactions with pam17-Δ, we assessed the generality of the synthetic genetic interactions of pam17-Δ with alterations affecting translocon association. Specifically, we tested for genetic interactions with pam16Δ1-12 and pam18ΔIMS. Like tim44Δ51-68 and tim44Δ68-82, pam16Δ1-12 had a severe genetic interaction with pam17-Δ. Although pam16Δ1-12pam17-Δ cells were recovered on 5-FOA plates, they grew extremely poorly at all temperatures tested (Figure 4C, Table 1). On the other hand, pam18ΔIMS and pam17-Δ showed no genetic interaction, growing as well as wt cells (Figure 4D).

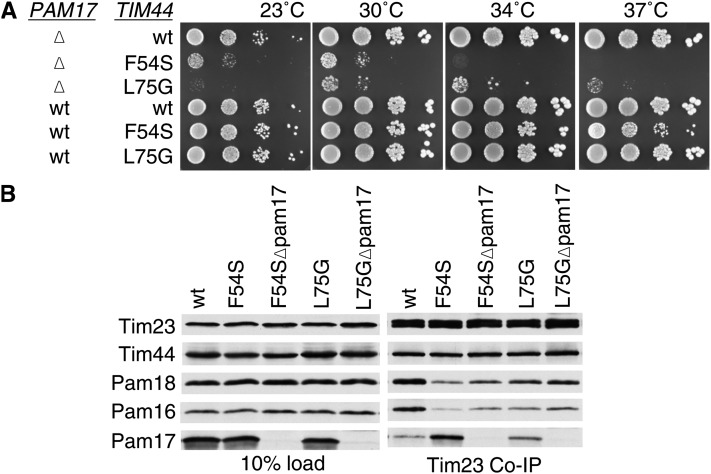

Single amino alterations cause similar phenotypic effects as deletions in N terminus of Tim44

We were concerned that the interpretation of our results might be compromised by perturbation of the overall structure of Tim44 caused by deletion of internal segments. Therefore, we made use of the strong synthetic interaction between pam17-Δ and TIM44 internal deletion mutations to screen for point mutations in TIM44 that affected function. A library was created that contained TIM44 on a TRP1-marked plasmid, which was randomly mutagenized in the first 113 codons. The library was transformed into pam17-Δ tim44-Δ cells carrying a wt copy of TIM44 on a URA3-marked plasmid. Transformants were selected on Trp− plates at 30° and screened for slow or no growth on 5-FOA plates at 37°. Two alleles having mutations that altered a single amino acid were isolated, F54S and L75G (Figure 5A). In an otherwise wt background, cells expressing Tim44F54S were temperature sensitive for growth, while those expressing Tim44L75G grew very similarly to wt. In the absence of Pam17, growth of cells also having the tim44F54S mutation grew extremely poorly at all temperatures tested; pam17-Δ tim44L75G cells grew nearly as poorly (Figure 5A). We also carried out co-immunoprecipitation assays. More Pam17 was coprecipitated with the translocon from tim44F54S lysates than wt lysates (Figure 5B), consistent with the analysis of the internal deletion tim44Δ51-68.

Figure 5 .

TIM44 point mutations having a strong synthetic interaction with pam17-Δ. (A) Growth phenotype. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam17-Δ tim44-Δ cells expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (B) Co-immunoprecipitation with Tim23. Equivalent amounts of purified mitochondria from the indicated TIM44 and PAM17 mutant strains were solubilized in buffer containing 1% digitonin. The cleared supernatants were incubated with protein A beads cross-linked to Tim23-specific antibody. The samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Tim23-, Tim44-, Pam18-, Pam16-, and Pam17-specific antibodies. Ten percent of total soluble material after lysis (10% load) was used as a loading control.

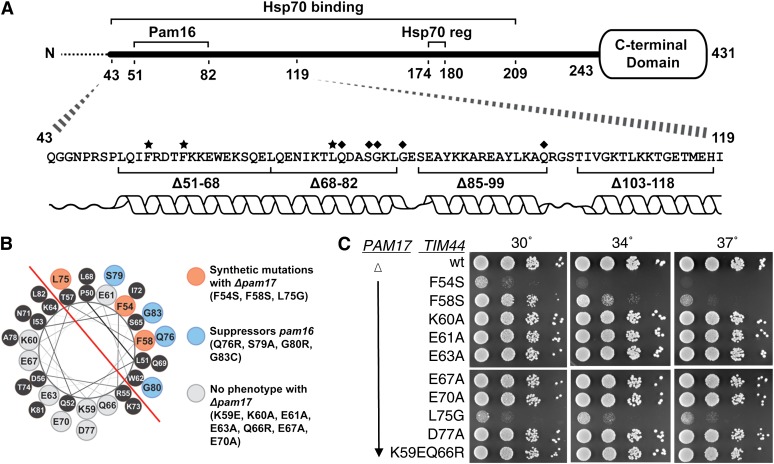

Distribution of amino acid alterations in Tim44 affecting interaction with Pam16

Secondary structure predictions suggest that the N terminus of Tim44 forms an α-helix from 51–80 (Figure 6A). One face of the proposed helix is quite hydrophobic and the opposite highly charged, as shown in a helical wheel diagram (Figure 6B). The amino acid alterations caused by two point mutations in TIM44, F54S and L75G, which were isolated on the basis of synthetic genetic interactions with pam17-Δ, fall on the hydrophobic face. In addition, previously identified suppressors in TIM44 (Q76, S79, G80, and G83) that partially overcome the defects caused by amino acid substitutions in the N terminus of Pam16 also fall on the hydrophobic face of the proposed helix (Figure 6B). To further test the importance of the hydrophobic face, F58 was changed to S and tested in the pam17-Δ tim44-Δ strain. Like F54S and L75G, F58S had a strong synthetic interaction with pam17-Δ (Figure 6C).

Figure 6 .

Residues involved in Tim44’s interaction with Pam16 fall on one side of Tim44’s predicted N-terminal α-helix. (A) Overview of Tim44. (Bottom) Residues altered by point mutations previously shown to suppress PAM16 mutations (D’Silva et al. 2008) are marked with a ♦. Residues altered by point mutations isolated in this study are marked with a ★. α-Helical prediction is shown below the sequence. (Top) Residues 174–180 implicated in regulation of Hsp70 binding (Hsp70 reg). Segment 43–209 is sufficient for Hsp70 binding in vitro (Schiller et al. 2008). Dotted line indicates the presequence that is removed upon entry into the matrix and thus not part of the mature protein. (B) Helical wheel showing Tim44 residues from P50 to G83. Red line demarks the hydrophobic side from the hydrophilic side of the helix. Tim44 residues identified in a suppressor screen of a PAM16 mutation are shown in blue. Tim44 residues that were identified in a TS screen using a PAM17 deletion background are shown in orange. Residues marked in gray were found not to have a synthetic interaction with a PAM17 deletion when altered as indicated. (C) Growth phenotype. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam17-Δ tim44-Δ cells carrying a plasmid expressing the indicated Tim44 variants were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. Spaces represent separate plates dropped at the same time.

With a goal of testing the functional importance of the charged helical face, we constructed alleles that converted individual charged residues to alanines: K60, E63, E67, E70, and D77. In addition, we constructed the double mutant K59E/Q66R, because K59 and Q66 were the two, of a total of six, residues altered that were within the N-terminal 239 amino acids, in a previously described temperature-sensitive TIM44 mutant, tim44-804 (Hutu et al. 2008). None of these alleles displayed growth defects either alone or in combination with a deletion of PAM17 (Figure 6C, data not shown). In addition, we created an allele that encoded an alteration of the only charged residue on the hydrophobic face, E61, to an alanine. It also had no phenotypic affect either alone or in combination with a deletion of PAM17 (Figure 6C, data not shown).

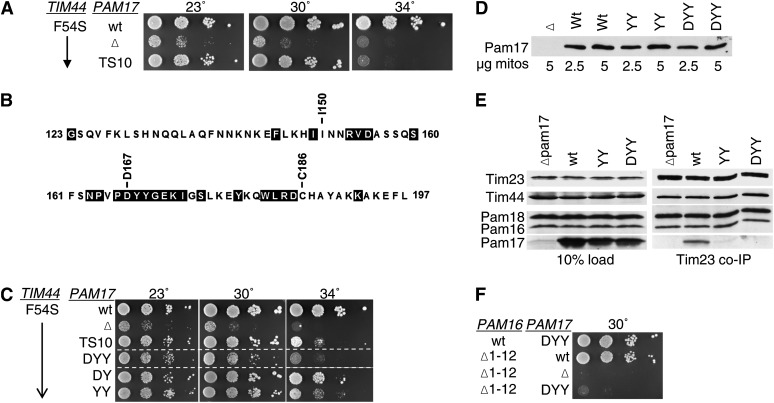

Importance of C-terminal matrix domain of Pam17 for its association with the translocon

To better understand Pam17 function, we attempted to obtain mutants encoding single-amino-acid alterations by carrying out random mutagenesis of full-length PAM17 and screening for temperature-sensitive mutants in the presence of the tim44F54S allele to sensitize the background. No alleles encoding single-amino-acid changes showing such a defect were identified. However, a triple mutant, TS10, encoding alterations at positions I150, D167, and C186, to N, A, and R, respectively, was isolated. pam17ts10tim44F54S cells were temperature sensitive for growth at 34°, but grew as well as tim44F54S cells having the wt PAM17 gene at 30° (Figure 7A). We tested each residue change individually. However, none of the single changes caused an obvious phenotype (data not shown). We then analyzed the sequences of 10 fungal Pam17 orthologs, searching for regions of particularly conserved sequences to choose for site-directed mutagenesis (Figure 7B). Residues within the 165–185 interval were particularly conserved. Since D167 was a highly conserved residue within this region, we constructed an allele encoding alterations of residues 167–169, all to alanine. The pam17DYY/AAA phenotype was more severe than that of pam17ts10, as pam17DYY/AAAtim44F54S cells also grew slowly at 30° (Figure 7C). Single- and double-alanine-substitution mutations were constructed within this interval. The growth phenotypes of the double mutants pam17YY/AA and pam17DY/AA were only slightly less severe than that of pam17DYY/AAA (Figure 7C). These variants were expressed at levels equivalent to wt Pam17 (Figure 7D).

Figure 7 .

Pam17’s C-terminal domain is important for Tim23 association. (A and C) A TS mutation in PAM17 identified in a strain expressing tim44F54S. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam17-Δ tim44-Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. PAM17 point mutants tested: original TS allele (TS10); alteration of residues D167, Y168, Y169 to A (DYY), D167 and Y168 to A (DY), Y168, Y169 to A (YY). Spaces represent separate plates dropped at the same time. (B) Sequence of the C-terminal matrix-exposed region of Pam17 orthologous proteins. Residues 123–197 of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein were aligned as described in Materials and Methods with 10 Pam17 sequences from a wide range of fungi: S. cerevisiae (National Center for Biotechnology Information RefSeq protein accession no. of S. cerevisiae Pam17p, NP_012991), Vanderwaltozyma polyspora (XP_001646868), Ashbya gossypii (NP_984424), Candida albicans (XP_720069), Yarrowia lipolytica (XP_500446), Neurospora crassa (XP_964390), Aspergillus fumigatus (XP_749937), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (NP_593381), Cryptococcus neoformans (XP_572177), and Ustilago maydis (XP_759477). Residues shaded in black are identical in at least 8 of the 10 sequences. (D) PAM17 mutants are expressed at wt levels. Purified mitochondria from the indicated PAM17 mutant strains were separated on SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted against Pam17-specific antibodies. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation with Tim23. Equivalent amounts of purified mitochondria from the indicated PAM17 mutant strains were solubilized in buffer containing 1% digitonin. The cleared supernatants were incubated with protein A beads cross-linked to Tim23-specific antibody. The samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Tim23-, Tim44-, Pam18-, Pam16-, and Pam17-specific antibodies. Ten percent of total soluble material after lysis was used as a loading control. (F) Synthetic interaction between PAM17 mutations and pam16Δ1-12. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam17-Δ pam16-Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at 30° for 3 days.

To assess the association of Pam17DYY/AAA and Pam17YY/AA with the translocon, co-immunoprecipitation assays were carried out. Co-immunoprecipitation of Pam17 with the translocon was severely compromised in extracts from both mutants, while the amount of Tim44, Pam18, and Pam16 precipitated was similar to that from wt extracts (Figure 7E). Thus, alteration of tyrosines 168 and 169 of Pam17 affects its association with the translocon. The genetic interaction of the pam17DYY/AAA and pam17-Δ alleles was also compared with pam16Δ1-12. pam17DYY/AAA and pam17-Δ had similar severe genetic interactions with pam16Δ1-12 (Figure 7F).

A “simple” model to explain the increase in association of Pam17 with the translocon observed when the Tim44:Pam16 interaction was disrupted, for example in the case of tim44Δ51-68 and tim44F54S (Figures 4B and 5B), would be that the binding of Pam17 and Pam16 to Tim44 is mutually exclusive. If this is the case, then disruption of Pam17 binding might result in an increase in Pam16 association. However, the amount of Pam16 immunoprecipitated from lysates of pam17-Δ, pam17DYY/AAA, and pam17YY/AA mitochondria, did not differ from that from wt lysates. In addition, the result shown in Figure 5B, indicates that the amount of Pam16 immunoprecipitating in tim44F54S lysates in the absence of Pam17 was only slightly greater than in its presence. Together, these results indicate that the absence of Pam17 binding to the translocon did not dramatically alter the association of Pam16 and thus provided no substantial evidence for a competition between the two proteins for overlapping binding sites.

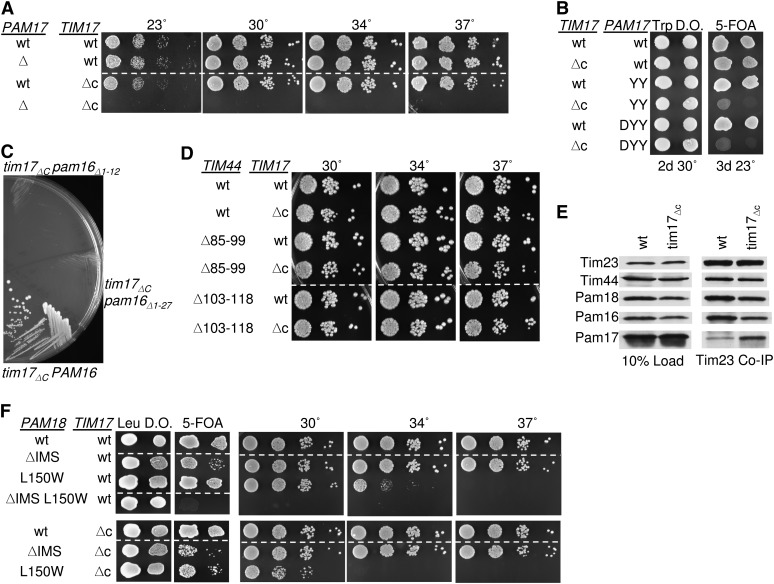

C terminus of Tim17 affects association of Pam17 and Pam16/18 with the translocon

During the course of another study, we noted that the pam17-Δ mutation had severe genetic interactions with a truncation allele of TIM17, tim17ΔC, lacking the segment encoding the C-terminal 24 residues, which is localized to the IMS. Because Tim17, a core component of the Tim23 translocon, has been implicated in the regulation of the channel (Martinez-Caballero et al. 2007) we pursued this observation. Consistent with a previous report (Meier et al. 2005), we found that cells expressing Tim17ΔC grew normally. However, a tim17ΔCpam17-Δ strain, although it could be recovered from five FOA plates, grew extremely poorly (Figure 8A, Table 1). Next, we tested the PAM17 mutations discussed above for genetic interaction with tim17ΔC. We found these double mutants, pam17DYY/AAAtim17ΔC and pam17YY/AAtim17ΔC to be as defective as pam17-Δ tim17ΔC (Figure 8B). Since pam17-Δ showed a strong synthetic interaction with TIM44 and PAM16 N-terminal mutations, we examined the interaction between tim17ΔC and these same mutations. tim17ΔC showed a similar pattern of synthetic interactions as pam17-Δ; pam16Δ1-12, tim44Δ51-68, and tim44Δ68-82 were synthetically lethal with tim17ΔC (Figure 8C, Table 1, data not shown), while tim44Δ85-99 and tim44Δ103-118 showed no synthetic interaction (Figure 8D).

Figure 8 .

Tim17 C-terminal domain is important for association of Pam16 and Pam18 with Tim23. (A and B) tim17ΔC is synthetically lethal with pam17-Δ. Tenfold serial dilutions of pam17-Δ tim17-Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (C) tim17ΔC is synthetically lethal with pam16Δ1-12. TIM17 PAM16 double deletion strains carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were streaked onto 5-FOA plates and incubated for 5 days at 23°. (D) Synthetic interactions between TIM44 mutations and tim17ΔC. Tenfold serial dilutions of tim44-Δ tim17-Δ cells carrying plasmids expressing the indicated proteins were plated on rich media and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. (E) Co-immunoprecipitation with Tim23. Equivalent amounts of purified mitochondria from the indicated PAM17 mutant strains were solubilized in buffer containing 1% digitonin. The cleared supernatants were incubated with protein A beads cross-linked to Tim23-specific antibody. The samples were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Tim23-, Tim17-, Tim44-, Pam18-, Pam16-, and Pam17-specific antibodies. Ten percent of total soluble material after lysis was used as a loading control. Tim17 was not assessed because the only antibody available is specific for the extreme C terminus. (F) pam18-Δ tim17-Δ strains, carrying PAM18 on a URA3-marked plasmid along with the indicated PAM18 mutants on pRS315 and the indicated Tim17 mutant on pRS314, were dropped on leucine drop out plates (Leu DO) and 5-FOA plates and incubated for 4 days at 23°. Viable strains from the 5-FOA plate were serially diluted, plated on rich media, and incubated at the indicated temperatures for 3 days. Dotted lines indicate where picture of same plate was cropped.

Since the pattern of genetic interactions described in the previous paragraph suggests that the Pam16:Tim44 interaction is critical in the absence of the C terminus of Tim17, just as it is in the absence of Pam17, we next tested the association of components with the Tim23 translocon in tim17ΔC mitochondria, again using Tim23-specific antibodies. We found an increase in co-immunoprecipitation of Pam17, while the association of Pam16/18 with the translocon was modestly reduced (Figure 8E). Also similar to pam17-Δ, little if any genetic interaction was observed between tim17ΔC and either pam18ΔIMS or pam18L150W, which encodes an alteration of the face of Pam18’s J domain that interacts with Pam16 (Figure 8F). Thus, the effects of deletion of PAM17 and the absence of the C-terminal IMS domain of Tim17 are similar with these PAM18 mutations.

Discussion

The import motor that drives protein translocation across the mitochondrial inner membrane is a complex and dynamic system. The results presented here add to our understanding of the translocation process by defining a region of Tim44 important for the interaction of Pam16 and thus the J-protein co-chaperone for Hsp70, Pam18. As discussed below, these results suggest a more complex role for Pam16’s interaction with the translocon than simply tethering. In addition, the genetic studies reveal a heretofore undetected role for the C-terminal domain of Tim17 in the function of the import motor.

Pam16 and the extreme N terminus of mature Tim44

As outlined in the previous sections, our results suggest that the N-terminal region of mature Tim44 is an interaction site for the N terminus of Pam16, thus serving to tether the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer to the translocon (Figure 2 and 3). At first glance, it is perhaps surprising that deletion of the segment of Tim44 that tethers the heterodimer has little phenotypic consequence. However, while most of the components of the import motor are essential proteins, as work has progressed to try to define specific interactions, the complexities and functional redundancies within the system have become apparent. For example, as earlier work indicated (Frazier et al. 2004; Kozany et al. 2004; Chacinska et al. 2005; D’Silva et al. 2005, 2008) and the results presented here extend, the association of the Pam16:Pam18 heterodimer with the translocon occurs through two interactions, one in the IMS via Pam18 and one in the matrix via Pam16. Disruption of either has rather modest effects on protein translocation and cell growth, while disruption of both has severe consequences. For example, pam18ΔIMS and pam16Δ1-12 are synthetically lethal. These genetic interactions are consistent with our observation that there is a synthetic lethal interaction between tim44Δ51-68 and pam18ΔIMS. We do note that in contrast to the relatively modest effects on growth in the absence of residues 51–68 of Tim44 we observed, it was previously reported that a TIM44 mutation causing an alteration of residue 67 from a glutamic acid to an alanine resulted in cell inviability (Slutsky-Leiderman et al. 2007). However, in our hands, this mutation had no obvious affect on cell growth (Figure 6C). The reason behind this apparent discrepancy remains unclear.

This pattern of genetic interactions among Pam18 and Pam16 alleles that affect translocon association allowed us to begin to dissect Tim44 function in relation to Pam16. Our results are consistent with the extreme N terminus of the mature form of Tim44 as being a site of interaction of the N terminus of Pam16. Deletions within this region had severe genetic interactions with mutations in PAM18, but at most mild genetic interactions with N-terminal deletions of PAM16. Although there is no direct structural information available for the N terminus of Tim44, secondary structure predictions presented here indicate a high propensity of α-helix formation (Figure 6A). The clustering of mutations that affect genetic interactions with PAM16 and PAM17 suggests that the hydrophobic face of this putative helix of Tim44 is the functionally important one for the interactions discussed here (Figure 6B). However, the highly charged nature of the opposite face and its conservation suggests that it may play an important, albeit yet to be defined, role as well.

Functional interactions of Pam17

The difference in the pattern of genetic interactions of the pam16Δ1-12 and the mutations altering the extreme N terminus of Tim44 with those in PAM18 affecting translocon association suggests that there may be specialization of the function of the N terminus of Pam16 beyond simple tethering to the translocon. The PAM18 mutation, pam18ΔIMS, had no genetic interaction with a deletion of PAM17, while the pam16Δ1-12 and the TIM44 mutations that alter the extreme N terminus of the mature protein, such as tim44Δ51-68 and tim44F54S, had very severe genetic interactions. However, this was not the case for all TIM44 mutations. For example, mutations causing nearby deletions, tim44Δ85-99 and tim44Δ103-118, showed no genetic interaction with pam17-Δ, even though tim44Δ103-118 had quite a severe genetic interaction with pam16Δ1-12.

The role of Pam17 remains enigmatic, but it has repeatedly been linked to a role in the association of Pam16:Pam18 with the translocon and the regulation of the conversion of the Tim23:Tim17 translocon complex between involvement in translocation of proteins into the matrix and the lateral insertion of proteins into the inner membrane (Van Der Laan et al. 2005; Hutu et al. 2008; Popov-Celeketic et al. 2008; Schiller et al. 2008; Schiller 2009). The results reported here extend the connection more specifically to the interaction between Tim44 and Pam16. In particular, the mutations that affect the interaction of Pam16 and Tim44 also affect the interaction of Pam17 with the translocon, leading to an increase in the amount of Pam17 co-immunoprecipitated. However, the increase in Pam17 association with the translocon cannot be explained simply by a competition between the two proteins for a binding site. As shown here, the absence of Pam17 has little affect on the amount of Pam16 associated with the translocon in the tim44F54S mutant. Similarly, the association of Pam17 with the translocon was not altered in the presence of a PAM16 mutation that affected its association with the translocon (Hutu et al. 2008). We think that the more likely explanation involves conformational changes in the components of the translocon and/or motor that affects its affinity for Pam17.

The results presented here also provide new information regarding the interaction of Pam17 with the translocon. Amino acid alterations within the highly conserved segment of the C-terminal matrix domain severely affect Pam17’s interaction with the translocon. However, further analysis will be required to determine the component of the translocon with which Pam17 directly interacts. Interestingly, Tim23 is the only component to which cross-linking to Pam17 has been observed (Hutu et al. 2008; Popov-Celeketic et al. 2008).

Similarity of genetic interactions of PAM17 and TIM17ΔC mutations

The results presented here uncovered a previously unknown connection between PAM17 and TIM17. pam17-Δ and a mutation having a deletion of the last 24 codons of TIM17 have an extremely strong genetic interaction. This result is particularly striking because of the robust growth of the individual mutants. No growth phenotype had been previously reported for cells lacking the C terminus of Tim17 (Meier et al. 2005). However, patch clamp analysis of Tim23 channels revealed a small effect of deletion of the C terminus of Tim17 (Martinez-Caballero et al. 2007). While depletion of Tim17 resulted in loss of the typical twin pore structure into a single pore and loss of voltage dependence, the translocons formed with the deletion of the C terminus maintained voltage and were twin pores, but more variable in size indicating some perturbation in structure/function. Like the pam17-Δ mutation, the tim17ΔC mutation was synthetically lethal with pam16Δ1-12, but had very modest interactions, if any, with the PAM18 ΔIMS mutation. However, the strong synthetic interaction between pam17-Δ and tim17ΔC indicates that Pam17 and the C terminus of Tim17 are not functionally redundant. Further work will be required to understand the mechanistic details behind these genetic interactions and to understand the function of both Pam17 and the C terminus of Tim17.

Possible modes of regulation of activity of the import motor

An aspect of the function of the import motor that has been heavily discussed is the idea that the activity of the J domain of Pam18 is regulated, to prevent a futile cycle of ATP hydrolysis and nucleotide exchange of Hsp70. The most prominent model over the past few years purports that the conformational alterations of the interface between Pam16 and Pam18 J-type domains regulate the stimulatory ability of Pam18. However, recent results obtained during an analysis of the PAM18 and PAM16 heterodimer indicate that this interface is not the basis of the biologically relevant alteration of ATPase stimulatory ability (Pais et al. 2011). In light of these recent results and the results reported here, it is tempting to speculate that it is the interaction between the N termini of Pam16 and Tim44 that serves such a regulatory purpose.

The results reported here implicate residues 51–82 of Tim44 in the tethering of Pam18, via Pam16, to the translocon. Residues 43–209 of Tim44 are sufficient for Hsp70 binding, with residues 174–180 implicated in regulation of the interaction (Merlin et al. 1999; Schiller et al. 2008) (Figure 6A). Thus Hsp70 and Pam18 are in close proximity when at the translocon. Certainly with such a close proximity, it is possible to imagine a conformational change within the N terminus of Tim44 that could toggle Pam18’s J domain between a position allowing for efficient stimulation of Hsp70 to one slightly out of alignment, and thus functionally in an inactive orientation. If such a situation existed, to make translocation an efficient process Tim44 would need to sense a signal that a polypeptide was entering the channel and thus motor activity was needed. The nature of such a signal is truly speculative, but the similarities in the genetic interactions between the pam17-Δ and tim17ΔC mutations and the increased association of Pam17 with the translocon upon the disruption of the Pam16:Tim44 interaction or loss of the C terminus of Tim17, points to a connection between the function of these components. The localization of Pam17 and Tim17 C termini on opposite sides of the membrane may serve as a means of communication across the membrane from the IMS where a polypeptide enters the translocon and the matrix where motor activity is required. Testing of such models generated from the genetic data presented will require assessment by biochemical and cell biological approaches.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jaroslaw Marszalek and June Pais for helpful discussions and Nikolaus Pfanner for antibody to Tim17. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant GM027870 (E.A.C.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: A. P. Mitchell

Literature Cited

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J., 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., et al. , 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M. F., Sirrenberg C., Neupert W., Brunner M., 1996. Role of Tim23 as voltage sensor and presequence receptor in protein import into mitochondria. Cell 87: 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacinska A., Lind M., Frazier A. E., Dudek J., Meisinger C., et al. , 2005. Mitochondrial presequence translocase: switching between TOM tethering and motor recruitment involves Tim21 and Tim17. Cell 120: 817–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Silva P. D., Schilke B., Walter W., Andrew A., Craig E. A., 2003. J protein cochaperone of the mitochondrial inner membrane required for protein import into the mitochondrial matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 13839–13844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Silva P. R., Schilke B., Walter W., Craig E. A., 2005. Role of Pam16’s degenerate J domain in protein import across the mitochondrial inner membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 12419–12424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Silva P. R., Schilke B., Hayashi M., Craig E. A., 2008. Interaction of the J-protein heterodimer Pam18/Pam16 of the mitochondrial import motor with the translocon of the inner membrane. Mol. Biol. Cell 19: 424–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloche O., Georgopoulos C., 1996. Purification and biochemical properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae’s Mge1p, the mitochondrial cochaperone of Ssc1p. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 23960–23966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Yamano K., 2009. Multiple pathways for mitochondrial protein traffic. Biol. Chem. 390: 723–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier A. E., Dudek J., Guiard B., Voos W., Li Y., et al. , 2004. Pam16 has an essential role in the mitochondrial protein import motor. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11: 226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M., 2009. Converging concepts of protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16: 574–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutu D. P., Guiard B., Chacinska A., Becker D., Pfanner N., et al. , 2008. Mitochondrial protein import motor: differential role of Tim44 in the recruitment of Pam17 and J-complex to the presequence translocase. Mol. Biol. Cell 19: 2642–2649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P., Halladay J., Craig E. A., 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144: 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampinga H. H., Craig E. A., 2010. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 579–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozany C., Mokranjac D., Sichting M., Neupert W., Hell K., 2004. The J domain-related cochaperone Tim16 is a constituent of the mitochondrial TIM23 preprotein translocase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11: 234–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Dudek J., Guiard B., Pfanner N., Rehling P., et al. , 2004. The presequence translocase-associated protein import motor of mitochondria. Pam16 functions in an antagonistic manner to Pam18. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 38047–38054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Krzewska J., Liberek K., Craig E. A., 2001. Mitochondrial Hsp70 Ssc1: role in protein folding. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 6112–6118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., D’Silva P., Walter W., Marszalek J., Craig E. A., 2003. Regulated cycling of mitochondrial Hsp70 at the protein import channel. Science 300: 139–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maarse A. C., Blom J., Grivell L. A., Meijer M., 1992. MPI1, an essential gene encoding a mitochondrial membrane protein, is possibly involved in protein import into yeast mitochondria. EMBO J. 11: 3619–3628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom M., Azem A., Mokranjac D., 2011. Understanding the molecular mechanism of protein translocation across the mitochondrial inner membrane: still a long way to go. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808: 990–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Caballero S., Grigoriev S. M., Herrmann J. M., Campo M. L., Kinnally K. W., 2007. Tim17p regulates the twin pore structure and voltage gating of the mitochondrial protein import complex TIM23. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 3584–3593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M. P., Bukau B., 2005. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62: 670–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier S., Neupert W., Herrmann J. M., 2005. Conserved N-terminal negative charges in the Tim17 subunit of the TIM23 translocase play a critical role in the import of preproteins into mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 7777–7785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin A., Voos W., Maarse A. C., Meijer M., Pfanner N., et al. , 1999. The J-related segment of tim44 is essential for cell viability: a mutant Tim44 remains in the mitochondrial import site, but inefficiently recruits mtHsp70 and impairs protein translocation. J. Cell Biol. 145: 961–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao B., Davis J. E., Craig E. A., 1997. Mge1 functions as a nucleotide release factor for Ssc1, a mitochondrial Hsp70 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 265: 541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokranjac D., Sichting M., Neupert W., Hell K., 2003. Tim14, a novel key component of the import motor of the TIM23 protein translocase of mitochondria. EMBO J. 22: 4945–4956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokranjac D., Bourenkov G., Hell K., Neupert W., Groll M., 2006. Structure and function of Tim14 and Tim16, the J and J-like components of the mitochondrial protein import motor. EMBO J. 25: 4675–4685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokranjac D., Berg A., Adam A., Neupert W., Hell K., 2007. Association of the Tim14.Tim16 subcomplex with the TIM23 translocase is crucial for function of the mitochondrial protein import motor. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 18037–18045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pais J. E., Schilke B., Craig E. A., 2011. Re-evaluation of the role of the Pam18:Pam16 interaction in translocation of proteins by the mitochondrial Hsp70-based import motor. Mol. Biol. Cell 22: 4740–4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollastri G., Przybylski D., Rost B., Baldi P., 2002. Improving the prediction of protein secondary structure in three and eight classes using recurrent neural networks and profiles. Proteins 47: 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov-Celeketic D., Mapa K., Neupert W., Mokranjac D., 2008. Active remodelling of the TIM23 complex during translocation of preproteins into mitochondria. EMBO J. 27: 1469–1480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassow J., Maarse A. C., Krainer E., Kubrich M., Muller H., et al. , 1994. Mitochondrial protein import: biochemical and genetic evidence for interaction of matrix hsp70 and the inner membrane protein MIM44. J. Cell Biol. 127: 1547–1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost B., 2001. Review: protein secondary structure prediction continues to rise. J. Struct. Biol. 134: 204–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K. R., Leung R. S., Jensen R. E., 1998. Characterization of the mitochondrial inner membrane translocase complex: the Tim23p hydrophobic domain interacts with Tim17p but not with other Tim23p molecules. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 178–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller D., 2009. Pam17 and Tim44 act sequentially in protein import into the mitochondrial matrix. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41: 2343–2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller D., Cheng Y. C., Liu Q., Walter W., Craig E. A., 2008. Residues of Tim44 involved in both association with the translocon of the inner mitochondrial membrane and regulation of mitochondrial Hsp70 tethering. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 4424–4433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O., Pfanner N., Meisinger C., 2010. Mitochondrial protein import: from proteomics to functional mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11: 655–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H. C., Berthold J., Bauer M. F., Dietmeier K., Guiard B., et al. , 1994. Mitochondrial Hsp70/MIM44 complex facilitates protein import. Nature 371: 768–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P., 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutsky-Leiderman O., Marom M., Iosefson O., Levy R., Maoz S., et al. , 2007. The interplay between components of the mitochondrial protein translocation motor studied using purified components. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 33935–33942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J., 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truscott K. N., Kovermann P., Geissler A., Merlin A., Meijer M., et al. , 2001. A presequence- and voltage-sensitive channel of the mitochondrial preprotein translocase formed by Tim23. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8: 1074–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truscott K. N., Voos W., Frazier A. E., Lind M., Li Y., et al. , 2003. A J-protein is an essential subunit of the presequence translocase-associated protein import motor of mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 163: 707–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan M., Chacinska A., Lind M., Perschil I., Sickmann A., et al. , 2005. Pam17 is required for architecture and translocation activity of the mitochondrial protein import motor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 7449–7458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan M., Hutu D. P., Rehling P., 2010. On the mechanism of preprotein import by the mitochondrial presequence translocase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1803: 732–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisine C., Cheng Y. C., Ohlson M., Schilke B., Hoff K., et al. , 2001. Jac1, a mitochondrial J-type chaperone, is involved in the biogenesis of Fe/S clusters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 1483–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]