Abstract

Objective:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health issue, yet little is known about the association between IPV victimization and problem drinking among women. Study objectives were to (a) identify subtypes of problem drinking among women according to abuse and dependence criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV); (b) examine the association between recent IPV and the problem drinking classes; and (c) evaluate major depressive disorder (MDD) as a mediator of the IPV-alcohol relationship.

Method:

Data come from a cohort of 11,782 female current drinkers participating in Wave 2 (2004–2005) of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Latent class analysis was used to group participants into problem drinking classes according to 11 DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria. The IPV measure was derived from six questions regarding abusive behaviors perpetrated by a romantic partner in the past year. Past-year MDD was assessed according to DSM-IV criteria. Latent class regression was used to test the association between drinking class and IPV.

Results:

Three classes of problem drinkers were identified: Severe (Class 1: 1.9%; n = 224), moderate (Class 2: 14.2%; n = 1,676), and nonsymptomatic (Class 3: 83.9%; n = 9,882). Past-year IPV was associated with severe and moderate classes (severe: adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 5.70, 95% CI [3.70, 8.77]; moderate: aOR = 1.92, 95% CI [1.43, 2.57]). Past-year MDD was a possible mediator of the IPV–drinking class relationship.

Conclusions:

Results indicate a strong association between recent IPV and problem drinking class membership. This study offers preliminary evidence that programs aimed at preventing problem drinking among women should take IPV and MDD into consideration.

Nearly 3 in 10 u.s. adults engage in high-risk drinking patterns, sometimes called problem drinking, that are linked with increased adverse health outcomes and risk of injury and violence (Leadley et al., 2000; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2006). Although alcohol use historically has been less among women compared with men, evidence suggests that the gender gap in severity of problem drinking is narrowing, particularly for heavy drinking, lifetime consumption, and, among younger cohorts, diagnoses of alcohol abuse and dependence (Greenfield et al, 2010; Keyes et al, 2008). Prior research has noted differential risk for problem drinking and alcohol use disorders (AUDs) according to race/ethnicity subgroups (Grant et al, 2004a; Kalaydjian et al, 2009), although few studies examine such differences within gender categories (Alvanzo et al, 2011).

Alcohol misuse has been linked with intimate partner violence (IPV). The association between alcohol and male-to-female IPV perpetration is well characterized in current literature (Coker et al, 2000; Foran and O'Leary, 2008; Hove et al, 2010; Jewkes, 2002; Klostermann et al, 2009; McKinney et al, 2010; O'Leary and Schumacher, 2003), but little is known about IPV victimization in the epidemiology of problem drinking among women (Klostermann and Fals-Stewart, 2006). IPV is associated with negative health outcomes for women, including alcohol and substance use, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, chronic disease, and interpersonal problems (Campbell et al, 2002; Coker et al, 2002; Plichta, 2004; Rees et al, 2011).

To date, studies evaluating the IPV victimization and alcohol relationship have done so primarily using samples obtained from clinical, court, shelter, or health care systems using standard alcohol measures (i.e., alcohol frequency and quantity), or AUD (presence/absence) as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Caetano et al., 2000; Cohn et al., 2010; Foran and O'Leary, 2008; Shannon et al., 2008). However, traditional regression methods often mask the heterogeneity in drinking profiles or subtypes (McCutcheon, 1987). In contrast, latent class analysis (LCA) enables researchers to identify homogeneous groups of individuals who share similar patterns of symptom or criteria endorsement and to model the association between these patterns or ‘classes’ of individuals and various outcomes, such as IPV (McCutcheon, 1987).

In the current study, we used LCA to examine subtypes of problem drinking among women. This is both beneficial and timely given that the proposed revisions to DSM-IV criteria suggest a change from a categorical to a dimensional approach to AUDs (Borges et al., 2011). Specifically, current diagnostic criteria may miss individuals with subthreshold disorders, affecting treatment receipt for alcohol problems (Ko et al., 2010). In contrast to analytic approaches based on criteria counts, LCA provides a more nuanced look at individual symptoms and their potential to establish a hierarchy of severity of alcohol use, not just their presence in number. Few previous studies using LCA with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms have examined this issue among adult, population-based samples, and none have investigated the association with IPV (Ko et al., 2010; Moss et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 1998).

The interrelationship between IPV, problem drinking, and major depressive disorder (MDD) remains unclear. The self-medication hypothesis of alcohol use suggests that alcohol acts as an anxiolytic agent to reduce and disable anxiety (Khantzian, 1997). Consistent with a self-medication theory, women may be more motivated than men to consume alcohol out of response to stress (Greenfield et al., 2010). Available cross-sectional research assessing the impact of prior violence victimization on women's problem drinking supports a self-medication model (Corbin et al., 2001; Ullman et al., 2006). Evidence for a self-medication model is bolstered by longitudinal studies reporting associations between prior victimization and future alcohol use directly (Kilpatrick, 1997; Thompson et al., 2008; Widom et al., 2006) and indirectly through mood disorders such as MDD, a psychiatric consequence shared by many victims of violence (Clark et al., 2003; Golding, 1999; Madruga et al., 2011).

Gender studies of alcohol use have revealed differences between men and women with respect to tolerance, heavy drinking, time spent in drinking-related activities, physical illness, and harmful social consequences (Nichol et al., 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). Related research by Muthén (2006) described latent variable approaches to characterize DSM-IV AUDs among men. In that study, LCA was applied to the 11 DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria among a representative cohort of male current drinkers. Results yielded four distinct alcohol problem subtypes based on severity profiles ranging from low to high symptom endorsement (Muthén, 2006). The two most severe problem drinking classes comprised men with high endorsement of hazardous drinking and alcohol dependence criteria, with social impairment (major role failure and social problems) distinguishing the most severe classes.

Motivated by findings of gender differences in alcohol use, the present study extends the work of Muthén by using LCA to identify classes of problem drinking among women based on DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria. This research further examines the complex associations between IPV, MDD, and problem drinking among female alcohol users by assessing the relationship between IPV and alcohol problem subtype. Classes corresponding to a hierarchy of problem drinking severity are expected, as are differential criteria for problem drinking versus non-problem-drinking classes. The purpose of the present study is to use LCA to identify subtypes of problem drinking among women in the U.S. general population according to 11 DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence, assess the relationship of past-year IPV with these alcohol problem subtypes, and explore MDD as a potential mediator of the IPV-alcohol relationship.

Method

Study population

Data for this study came from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Consequences (NESARC), a nationally representative survey of 43,093 civilian participants ages 18 or older in the United States. The study was conducted in 2001–2002 (Wave 1) with a follow-up in 2004–2005 (Wave 2). Face-to-face interviews were conducted with eligible participants for an overall 81% retention rate. Sampling procedures and retention strategies are described elsewhere (Grant et al., 2004a). Nearly 40% of the sample (n = 7,879) reported abstinence from alcohol at Wave 2 interview and were excluded. The analyses presented were restricted to 11,782 women identified as current drinkers (respondents who reported drinking at least one alcoholic beverage in the past year) at Wave 2 (Mage = 45.3 years, SD = 16.12); 82.1% of women in this cohort reported currently being in a relationship.

Measures

Alcohol use.

Alcohol abuse and dependence criteria were assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS-IV), a structured diagnostic interview designed primarily to assess alcohol, drug, and mental disorders according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria (Grant et al., 2003). The present analyses focused on four alcohol abuse criteria and seven alcohol dependence criteria created as binary variables from a set of past-year symptom questions and used to form the outcome latent classes. Alcohol abuse criteria included recurrent drinking resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations, recurrent drinking in hazardous situations, recurrent drinking-related legal problems, and continued drinking despite recurrent interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by drinking. Alcohol dependence criteria included tolerance; having two or more withdrawal symptoms; drinking larger amounts or for a longer period than intended; having a persistent desire or unsuccessful attempts to cut down on drinking; spending a great deal of time obtaining alcohol, drinking, or recovering from drinking's effects; giving up important social, occupational, or recreational activities to drink; and continued drinking despite physical or psychological problems caused by drinking (Muthén, 2006). Past-year AUD measured at Wave 1 was included as a categorical control variable (0 = no AUD, 1 = abuse only, 2 = dependence only, 3 = both abuse and dependence). Reliability and validity of the AUDADIS-IV modules are reportedly good (Grant et al., 2003; Ruan etal., 2008).

Intimate partner violence.

Consistent with prior research (Ruan et al., 2008), a binary IPV (primary exposure) measure was derived as a composite from questions adopted from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) regarding six abusive behaviors perpetrated by a spouse or romantic partner in the 12 months preceding Wave 2: (a) pushing, grabbing, or shoving; (b) slapping, kicking, biting, or hitting; (c) threatening with a weapon such as a knife or gun; (d) cutting or bruising; (e) having forced sex; and (f) inflicting an injury that required medical care. The reported internal consistency of IPV victimization items among the full cohort was acceptable (α = .73; Ruan et al., 2008), as it was among women in the current analysis (α = .74). Endorsement of any of the six abuse questions yielded an endorsement of past-year IPV.

Major depressive disorder.

The AUDADIS-IV was also used to assess past-year mood disorders, excluding those attributable to an underlying medical condition or induced by substance use (independent MDD) (Grant et al., 2004b). MDD was examined as a potential mediator in this study. A binary depression variable was created according to whether the respondent met criteria for a major depressive episode in the past year at Wave 2. The reported reliability for past-year MDD among the full cohort was good (κ = .59; Grant et al., 2003).

Sociodemographic characteristics.

Potential sociodemo-graphic confounders measured at Wave 2 were included in the analyses. Age was measured in years and included as categories 18–29 years, 30–49 years, and 50 years or older. Race/ethnicity was included as a categorical variable (0 = non-Hispanic White, 1 = non-Hispanic Black, 2 = Hispanic, 3 = other, including Asian and Native American women) with non-Hispanic Whites as the reference group. Relationship status was determined by self-report, and a binary variable was created from affirmative response to whether the woman was married, dating, or involved in a romantic relationship in the past year.

Statistical analyses

LCA is a “person-centered” approach used to describe the structure of an underlying categorical latent variable (i.e., class membership), which is assumed to influence endorsement of survey items. Conscious of several model fit indices, a likely class membership (posterior probability estimated using Bayesian techniques) is determined independently for each individual, and the probability of item endorsement within each mutually exclusive class is obtained (Nylund et al., 2007). Using the 11 categorical DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence criteria as indicators of problem drinking, a series of unrestricted latent class models (one to four classes) was fit to determine the appropriate number of classes. The best-fitting LCA model was extended using latent class regression (LCR) that permitted simultaneous exploration of the direct association between IPV as a main exposure, along with the covariates of age, race/ethnicity, relationship status, and prior AUD. LCR assumes both conditional independence and nondifferential measurement; within class, the measured indicators are uncorrelated with each other, and the covariates do not influence the indicators given class membership, respectively (Bandeen-Roche et al., 1997; Xue and Bandeen-Roche, 2002). On the premise that disparities may exist in problem drinking according to race/ethnicity, stratified analyses based on race/ethnicity subgroups were conducted.

Two separate LCR analyses were conducted to examine the association between IPV and class membership with and without MDD, adjusting for potential confounders. Latent class modeling was carried out using the MPlus software (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2010). A continuous weighting variable was included in all analyses to account for the NESARC's oversampling of young adults, Hispanics, and Blacks; nonresponse at the household and individual levels; and the selection of one individual per household.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of key variables are shown in Table 1. Overall proportions and counts of criteria endorsement are reported in Table 2. The proportion of criteria endorsement in the sample of women was moderately high for withdrawal symptoms (12.5%), drinking larger amounts or for longer periods than intended (10.8%), attempting to cut down on drinking (9.2%), and hazardous drinking (6.2%), whereas items such as having legal problems (0.3%) and major role failure (0.6%) were among the least prevalent criteria endorsed by this cohort.

Table 1.

Distribution of sociodemographic and alcohol characteristics for female current drinkers (N = 11,782), National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol-Related Conditions, 2003–2004

| Characteristics | n | Weighted % | Unweighted % |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 7,663 | 78.75 | 65.04 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1,960 | 9.21 | 16.64 |

| Hispanic | 1,891 | 8.98 | 16.05 |

| Other | 268 | 3.05 | 2.27 |

| Age, in years | |||

| 18–29 | 1,993 | 19.21 | 16.92 |

| 30–49 | 5,515 | 44.20 | 46.81 |

| ≥50 | 4,274 | 36.58 | 36.28 |

| Currently in intimate relationship | |||

| Yes | 9,091 | 82.08 | 77.16 |

| No | 2,691 | 17.92 | 22.84 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 1,139 | 8.55 | 9.99 |

| High school | 2,788 | 24.55 | 24.46 |

| Some college | 2,862 | 25.56 | 25.11 |

| College or more | 4,608 | 41.34 | 40.43 |

| Income, in U.S. $ | |||

| <$30,000 | 7,897 | 73.73 | 72.47 |

| $30,000–49,999 | 1,585 | 13.66 | 14.54 |

| $50,000–79,999 | 1,038 | 8.84 | 9.52 |

| ≥$80,000 | 377 | 3.77 | 3.46 |

| Intimate partner violence, past year | |||

| Yes | 687 | 5.30 | 5.83 |

| No | 11,095 | 94.70 | 94.17 |

| Alcohol use disorder at Wave 1 | |||

| Alcohol abuse | 550 | 4.36 | 4.67 |

| Alcohol dependence | 219 | 1.89 | 1.86 |

| Alcohol abuse + dependence | 284 | 2.46 | 2.41 |

| No | 10,729 | 91.30 | 91.06 |

| Drinking pattern, past year | |||

| Less than every day | 10,868 | 92.05 | 92.33 |

| Every day or nearly every day | 903 | 7.95 | 7.67 |

| Amount of alcohol consumed on drinking days, past-year | |||

| <5 drinks | 11,184 | 94.81 | 94.92 |

| ≥5 drinks | 598 | 5.19 | 5.08 |

| Major depressive disorder, past year | |||

| Yes | 1,406 | 11.81 | 11.93 |

| No | 10,376 | 88.19 | 88.07 |

Table 2.

Overall criteria weighted percentages and counts among female current drinkers in National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol-Related Conditions (N = 11,782)

| Symptom | % | n |

| Major role failure | 0.6 | 127 |

| Hazardous drinking | 6.2 | 1,236 |

| Legal problems | 0.3 | 64 |

| Social problems | 1.2 | 232 |

| Tolerance | 5.5 | 1,097 |

| Withdrawal | 12.5 | 2,504 |

| Larger amount | 10.8 | 2,175 |

| Cut down | 9.2 | 1,844 |

| Time spent | 1.9 | 389 |

| Give up | 0.6 | 113 |

| Physical/psychological problems | 3.4 | 686 |

Latent class analysis results

Three latent classes of drinkers were identified. A number of fit indices informed model selection, including the Akaike Information Criterion, sample-size-adjusted Bayes-ian Information Criterion, and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (McCutcheon, 1987; Nylund et al., 2007) (Table 3). Model selection was based on the best overall model indices and interpreted similarly to a scree plot, in which the best candidate model emerges at the level where the fit indices begin to level off (Muthén, 2004). Results showed that the Akaike Information Criterion, Bayesian Information Criterion, and sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion values decreased substantially with the addition of each class and began to level off after the third class. Substantive and clinical interpretation combined with model fit indices suggests that the three-class model is preferred, likelihood ratio χ2(2010) = 1,370, to the less parsimonious, higher-class models where class prevalence is deemed too low (<1%). The entropy for the three-class model was .875, suggesting an acceptable level of classification accuracy (Celeux and Soromenho, 1996).

Table 3.

Latent class analysis: Model fit indices

| Variable | Number of classes |

|||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Starts | 1000, 10a | 1000, 10a | 1000, 10a | 1000, 10a |

| Pearson χ2 | 27,350.271 | 3,624.189 | 1,535.220 | 1,478.955 |

| Pearson2p value | .00 | .9995 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| LRχ | 4,947.372 | 1,274.381 | 1,370.212 | 1,337.907 |

| df | 1,924 | 2,005 | 2,010 | 1,997 |

| Log likelihood | −22,040.849 | −17,967.877 | −17,441.467 | −17,363.414 |

| Parameters, n | 11 | 23 | 35 | 47 |

| AIC | 44,103.699 | 35,981.753 | 3,4952.935 | 34,820.828 |

| BIC | 44,184.816 | 36,151.361 | 35,211.036 | 35,167.422 |

| nBIC | 44,149.859 | 36,078.270 | 35,099.810 | 35,018.061 |

| LMRp | n.a. | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Entropy | n.a. | .903 | .875 | .874 |

Notes: LR = likelihood ratio; AIC = Akaike Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; nBIC = sample-size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin; n.a. = not available.

“Starts 1000, 10” indicates that 1,000 random sets of starting values for the initial stage and 10 final stage optimizations were used in the analysis.

Stratified analyses by race/ethnicity were conducted by fitting one to four class models with the 11 DSM-IV alcohol indicators for the non-Hispanic White women, non-Hispanic Black women, and Hispanic women. As with the full cohort, the three-class model was favored by fit statistics and substantive interpretation. Because the stratified analyses did not yield appreciable differences by race/ethnicity, the full cohort measurement model was retained for subsequent analyses.

The overall prevalence estimates and conditional probabilities of endorsement of items within each class were relatively consistent across the three-class model groups. Conditional independence was evaluated and met by checking pairwise odds ratios among selected items within each class. Under this assumption, within each class, items previously correlated were unrelated to each other. Of the 1,023 possible response patterns for the 11 abuse/dependence criteria, 254 patterns were observed in the data.

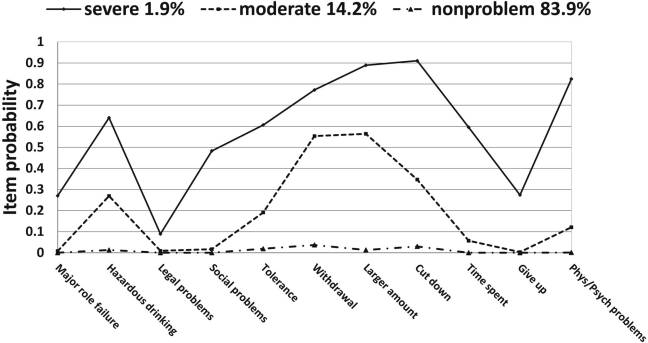

Figure 1 reports the item profile plot reporting conditional probabilities of symptom criteria by alcohol problem subtype for the three-class model. Classes were characterized by endorsement of 11 DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria. The nonsymptomatic class (83.9%; n = 9,882), the largest class prevalence, contained the nonproblem drinkers or those women who had low to no endorsement of any of the 11 abuse/dependence criteria. The nonsymptomatic class served as the reference group for subsequent class comparisons. The moderate class (14.2%; n = 1,676) contained drinkers who drank under physically hazardous conditions (26.9%) and who had moderate endorsement of alcohol dependence criteria. In contrast, severe drinkers (1.9%; n = 224) endorsed a greater number of alcohol abuse and dependence criteria—including larger amounts for longer periods (89.0%), unsuccessful attempts to cut down drinking (91.0%), continued drinking despite physical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by drinking (82.4%), withdrawal symptoms (77.2%), hazardous drinking (64.0%), continued drinking despite recurrent social problems (48.3%), major role failure (27.0%), and giving up important activities to drink (27.4%)—than moderate or nonsymptomatic drinkers.

Figure 1.

Weighted probability of endorsing abuse and dependence criteria given latent class among women current drinkers, National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2004–2005 (N= 11,782). Phys/psych = physical/psychological.

To gauge potential misclassification, the distribution of IPV, past-year AUD, and other key characteristics across latent classes was examined (Table 4). The prevalence of past-year IPV in this cohort of women was 5.3% (n = 687). Significant differences were noted comparing severe and moderate problem drinking subtypes, particularly with respect to IPV, prior AUD, MDD, and age. Compared with the moderate class, women in the severe drinking class were younger, had higher prevalence of IPV in the past year, and had higher prevalence of both prior AUD and MDD. The severe problem-drinking class contained the largest proportion (25.6%) of abused women, followed by the moderate problem-drinking class (9.0%). The lowest proportion of abused women was in the nonsymptomatic drinking class (4.3%). Similarly, the severe class also contained the highest proportion of women meeting DSM-IV criteria for dependence (32.4%), followed by the moderate class (11.9%). By contrast, only 1.6% of women in the nonsymptomatic class met DSM criteria for dependence, and 95.7% had no AUD.

Table 4.

Distribution of sociodemographic and alcohol characteristics by latent class membership for current female alcohol users (N = 11,782), National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol-Related Conditions, 2004–2005

| Variable | Class 1 severe |

Class 2 moderate |

Class 3 nonsymptomatic |

p* | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .34 | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 125 | 76.25 | 980 | 77.32 | 6,558 | 79.02 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 42 | 11.52 | 285 | 10.78 | 1,633 | 8.92 | |

| Hispanic | 25 | 5.78 | 247 | 9.54 | 1,619 | 8.96 | |

| Age, in years | <.0001 | ||||||

| 18–29 | 65 | 39.63a,b | 461 | 35.53c | 1,467 | 16.28 | |

| 30–49 | 112 | 50.45b | 816 | 48.05c | 4,587 | 43.48 | |

| ≥50 | 21 | 9.92a,b | 262 | 16.42c | 3,991 | 40.24 | |

| Currently in intimate relationship | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 164 | 87.3b | 1,299 | 86.65c | 7,628 | 81.27 | |

| No | 34 | 12.7 | 240 | 13.35 | 2,417 | 18.73 | |

| Intimate partner violence, past year | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 54 | 25.58a,b | 161 | 9.04c | 472 | 4.31 | |

| No | 144 | 74.43 | 1,378 | 90.96 | 9,573 | 95.69 | |

| Alcohol use disorder at Wave 1 | <.0001 | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 24 | 12.66a,b | 154 | 10.12c | 294 | 2.67 | |

| Alcohol dependence | 21 | 10.11a,b | 91 | 5.58c | 21 | 0.87 | |

| Alcohol abuse + dependence | 46 | 22.29a,b | 95 | 6.34c | 46 | 0.75 | |

| No | 107 | 54.94 | 1,199 | 77.96 | 9,597 | 95.7 | |

| Major depressive disorder, past year | <.0001 | ||||||

| Yes | 89 | 50.45a,b | 279 | 17.81c | 1,038 | 10.09 | |

| No | 109 | 49.55 | 1,260 | 82.19 | 9,007 | 89.91 | |

Difference between Class 1 and Class 2,p < .05;

difference between Class 1 and Class 3,p < .05;

difference between Class 2 and Class 3,p <.05.

Chi-square statistic with Bonferroni-adjusted p values.

Latent class regression results

The three-class measurement model was extended into an LCR model to include IPV as a main exposure, along with age, race/ethnicity, relationship status, and prior AUD. To test the influence of the interpersonal problems indicator on model results, sensitivity analyses were conducted in which this indicator was removed from both LCA and LCR estimations; no appreciable differences in regression estimates were noted. Table 5 presents class prevalence and estimated odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) between IPV and alcohol problem subtype for the fully adjusted model (the nonsymptomatic class as reference). The results indicate that problem-drinking class prevalence varies as a function of IPV, age, and prior AUD but not as a function of relationship status or race/ethnicity. Women with a recent history of IPV were more likely to be in a problem-drinking class than nonabused women after adjusting for potential confounders (severe class: adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 5.70, 95% CI [3.70, 8.77]; moderate class: aOR = 1.92, 95% CI [1.43, 2.57]). Age was negatively associated with membership in both the severe and moderate problem-drinking classes. In contrast, relationship status showed no significant association with either problem-drinking class. Prior AUD was strongly associated with alcohol subtype, particularly for the severe class.

Table 5.

Three-class latent class regression model: Odds of class membership given covariates among female current drinkers in National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol-Related Conditions (N = 11,782)

| Covariates | Severe classa |

Moderate classa |

Severe vs. moderate class |

|||||||

| OR | [95% CI] | aOR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] | aOR | [95% CI] | aOR | [95% CI] | |

| Excluding MDD | ||||||||||

| IPV | 8.50 | [5.42, 13.34] | 5.70 | [3.70, 8.77] | 2.53 | [1.93, 3.33] | 1.92 | [1.43, 2.57] | 2.97 | [1.89, 4.65] |

| Relationship | 1.50 | [0.87, 2.61] | 0.91 | [0.53, 1.58] | 1.71 | [1.36, 2.17] | 1.26 | [0.99, 1.59] | 0.72 | [0.40, 1.30] |

| Age, in years | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | 3.47 | [2.20, 5.42] | 6.75 | [3.54, 12.89] | 3.34 | [2.81, 4.00] | 6.30 | [4.88, 8.12] | 1.07 | [0.55, 2.06] |

| 30–49 | 1.34 | [0.87, 2.06] | 3.35 | [1.94, 5.81] | 1.35 | [1.13, 1.61] | 3.06 | [2.38, 3.95] | 2.41 | [0.61, 1.96] |

| ≥50 | 0.17 | [0.10, 0.30] | ref. | 0.22 | [0.17, 0.28] | ref. | ref. | |||

| Prior AUD | 6.61 | [5.13, 8.54] | 7.32 | [4.66, 11.48] | 4.11 | [3.17, 5.28] | 4.39 | [2.85, 6.76] | 1.65 | [1.43, 1.90] |

| Race/ethnicity | 1.15 | [0.82, 1.61] | 0.9 | [0.71, 1.38] | 0.99 | [0.90, 1.09] | 0.83 | [0.78, 0.95] | 1.15 | [0.82, 1.60] |

| Including MDD | ||||||||||

| IPV | – | – | 3.97 | [2.58, 6.12] | – | – | 1.77 | [1.32, 2.37] | 2.24 | [1.39, 3.59] |

| Relationship | – | – | 0.98 | [0.56, 1.73] | – | – | 1.28 | [1.01, 1.62] | 0.83 | [0.44, 1.53] |

| Age, in years | ||||||||||

| 18–29 | – | – | 6.55 | [3.50, 12.27] | – | – | 6.17 | [4.69, 8.12] | 1.06 | [0.55, 2.02] |

| 30–49 | – | – | 3.10 | [1.82, 5.26] | – | – | 3.00 | [2.33, 3.88] | 1.03 | [0.58, 1.83] |

| ≥50 | ref. | – | ref. | ref. | ||||||

| Prior AUD | – | – | 7.60 | [1.60, 11.72] | – | – | 4.53 | [2.88, 7.11] | 1.63 | [1.41, 1.89] |

| MDD | 10.80 | [6.88, 16.96] | 6.99 | [4.57, 10.82] | 2.12 | [1.71, 2.63] | 1.80 | [1.43, 2.28] | 4.17 | [2.65, 6.55] |

| Race/ethnicity | – | – | 0.98 | [0.73, 1.32] | – | – | 0.86 | [0.77, 0.97] | 1.16 | [0.86, 1.58] |

Notes: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; aOR = adjusted OR; MDD = major depressive disorder; IPV = intimate partner violence; AUD = alcohol use disorder; ref. = reference.

The nonsymptomatic class served as a reference group for both models.

Mediation by depression

To advance the hypothesis that abused women are likely to experience depression, which influences their drinking, MDD was entered into the fully adjusted model using the Baron–Kenny approach to mediation (Baron, 1986). The association of the main exposure, IPV, with class membership attenuated sharply yet remained statistically significant. In a model with MDD, women with history of IPV were more likely to be in the severe drinking class than non-abused women after adjusting for age, relationship status, race, and prior AUD (aOR = 3.97, 95% CI [2.58, 6.12]). The association between IPV and the moderate class also attenuated, suggestive of partial mediation (aOR = 1.77, 95% CI [1.32, 2.37]). Additionally, a significant association was observed between IPV exposure and MDD itself (aOR = 2.94, 95% CI [2.67, 3.22]). The Sobel (1982) product-of-coefficients test for the presence of mediation was also statistically significant (Sobel statistic = 8.71, p < .001).

Discussion

The present study yielded three classes of alcohol problem subtypes among a U.S. nationally representative cohort of women (overall and within each race/ethnicity subgroup): two problem-drinking (severe and moderate) classes and one nonsymptomatic class. The problematic classes were distinguished primarily by social problems, including giving up important activities to drink, and drinking despite physical or psychological problems. Prior LCA research of alcohol abuse and dependence criteria and symptomatology among other population-based cohorts and among male current drinkers in the NESARC reported a four-class model as the preferred solution (Ko et al., 2010; Muthén, 2006). By focusing on women, this research casts unique light on the heterogeneity among female current drinkers by identifying three distinct classes characterized by alcohol abuse and dependence criteria.

This study is one of the first to show that women in the general population with a recent history of IPV are more likely to be in a severe class of problem drinkers than non-abused women. Although prior research has established an association between violence and individual facets of drinking behavior (Breiding et al., 2008; Graham et al., 2011; O'Leary and Schumacher, 2003), this study demonstrates a direct relationship between IPV and subtypes of problem drinking and provides support for an indirect association via MDD.

These results support the hypothesized mediated relationship of IPV exposure and problem drinking class by MDD. Consistent with a self-medication theory, the strong associations observed between MDD and alcohol problem subtype and between IPV and MDD suggest that MDD may be a mechanism by which the outcome is produced. This was supported by the observed attenuation of the IPV main effect for the severe drinking class after inclusion of MDD in the fully adjusted model. Taken together, these results support partial mediation of IPV-problem drinking relationship by MDD, suggesting that other indirect paths may exist independent of MDD. This finding is consistent with prior studies suggesting that psychiatric conditions at least partly account for the relationship between prior trauma and alcohol use (Edwards et al., 2006; Sartor et al., 2010). The current study's results should be considered with longitudinal research by Fergus-son and colleagues, which suggests the causal direction flows from AUD to MDD (Fergusson et al., 2009). Yet other studies of community-dwelling men and women report that the relationship of MDD to AUD is established in both directions (e.g., Gilman and Abraham, 2001).

Limitations and strengths

This study's findings should be viewed in light of several limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the data restricts the ability to establish temporal ordering of IPV exposure, MDD, and AUD symptoms. The temporal uncertainty of exposure and outcome gives rise to the possibility of reverse causation (i.e., problem drinking leads to IPV victimization and MDD). A longitudinal design is needed to bolster evidence in favor of a self-medication model proposed by the current study. The present analyses were limited to a cross-sectional examination as IPV items were available only in NESARC Wave 2.

Although LCA accounts for imperfect measurement of key variables, AUD criteria, MDD criteria, and IPV exposure nonetheless are self-reported items and subject to misclassification bias. The study would have been additionally strengthened with the inclusion of information on IPV perpetration by the women themselves, as well their partners’ drinking patterns (Caetano et al., 2005; Sullivan et al., 2009; Testa et al., 2003; Wilsnack and Wilsnack, 1995). Future research should focus on the interplay of factors involved in reciprocal violence as they relate to the IPV-alcohol association.

The use of latent variable modeling in assessing the relationship between IPV and problem drinking confers several unique advantages. LCA assumes that items are measured imperfectly and estimates measurement error for categorical indicators (Flaherty, 2002). Current diagnostic approaches using criteria counts carry an assumption that all symptoms are weighted equally or carry the same potential for impairment. LCA permits use of all available information to describe a hierarchy of criteria, thus providing a nuanced look at individual criteria and their potential to distinguish a hierarchy of problem drinking severity, not just their presence in number. The current study provides insight into specific criteria that distinguish between classes of problem drinking severity among women: giving up important activities in favor of drinking, continue drinking despite physical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by drinking, failure to fulfill major roles, continued drinking despite recurrent social problems. In the current study, these four AUD criteria signal a level of significant impairment, interruption of daily functioning, and vulnerability to severe problem drinking among women. To examine the influence of MDD on latent class membership, individuals were assigned to latent classes using posterior probabilities as weights (Clark and Muthén, 2009). The study involves one of the largest cohorts of women available in a U.S. nationally representative epidemiological survey, marking the appropriateness of the data set to research on women's problem drinking and IPV.

These results should be considered with respect to proposed revisions to the definition of AUD. Such revisions conceptualize AUD as a single disorder of graded severity based on observed symptoms comprising criteria for both alcohol abuse and dependence. Discrete categories of abuse and dependence may no longer reflect the complexity of women's problem drinking and related risk factors. At the extreme, current diagnostic categories may not adequately address the needs of women whose alcohol symptoms warrant concern but who ultimately are ineligible for treatment because of absence of diagnosable disorder. In the current study, subtypes of problem drinking comprise both alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms. Although the three alcohol subtypes identified appear to differ by severity, the subset of symptoms that distinguishes between problem drinking classes signals a level of social impairment (e.g., major role failure, interpersonal and social problems, giving up of social activities) that otherwise might pass undetected. Interestingly, symptoms of social impairment characterized the most severe problem drinking classes among men also in the same study cohort (Muthén, 2006), suggesting that social impairment may be a hallmark feature of problem drinking in both sexes.

This study reports significant, consistent associations between recent IPV and problem drinking among a representative cohort of women. The results support the identification of IPV victimization as a risk factor for women's severe problem drinking characterized by social impairment. Future work in development of preventive interventions would benefit from considering the impact of IPV and MDD on women's alcohol use.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse Grant F31AA 018935-01A1 (to Lareina N. La Flair) and Grant AA016346 (to Rosa M. Crum).

References

- Alvanzo AA, Storr CL, La Flair L, Green KM, Wagner FA, Crum RM. Race/ethnicity and sex differences in progression from drinking initiation to the development of alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Miglioretti DL, Zeger SL, Rathouz PJ. Latent variable regression for multiple discrete outcomes. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1997;92:1375–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G. Threshold and optimal cut-points for alcohol use disorders among patients in the emergency department. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1270–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01462.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence–18 U.S. states/territories, 2005. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Clark CL, Schafer J. Intimate partner violence and drinking patterns among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, McGrath C, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Field CA. Drinking, alcohol problems and the five-year recurrence and incidence of male to female and female to male partner violence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:98–106. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150015.84381.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O'Campo P, Wynne C. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:1157–1163. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, De Bellis MD, Lynch KG, Cornelius JR, Martin CS. Physical and sexual abuse, depression and alcohol use disorders in adolescents: Onsets and outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S, Muthén B. Manuscript submitted for publication. Los Angeles: University of California; 2009. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook SM. Men's avoidance coping and female partner's drinking behavior: A high-risk context for partner violence? Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25:679–687. doi: 10.1007/s10896-010-9327-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ. Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: Physical, sexual, and psychological battering. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:553–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Bernat JA, Calhoun KS, McNair LD, Seals KL. The role of alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption among sexually victimized and nonvictimized college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C, Dunham D, Ries A, Barnett J. Symptoms of traumatic stress and substance use in a non-clinical sample of young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:2094–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Tests of causal links between alcohol abuse or dependence and major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:260–266. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty BP. Assessing reliability of categorical substance use measures with latent class analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;68(Supplement):7–20. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O'Leary KD. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abraham HD. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;63:277–286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Wilsnack SC, Gmel G. Alcohol may not cause partner violence but it seems to make it worse: A cross national comparison of the relationship between alcohol and severity of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:1503–1523. doi: 10.1177/0886260510370596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004a;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004b;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33:339–355. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove MC, Parkhill MR, Neighbors C, McConchie JM, Fossos N. Alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: The role of self-determination. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:78–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaydjian A, Swendsen J, Chiu W-T, Dierker L, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Kessler R. Sociodemographic predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use, disorders, and remission in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann K, Mignone T, Chen R. Subtypes of alcohol and intimate partner violence: A latent class analysis. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:563–576. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: Exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11:587–597. [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Martins SS, Kuramoto SJ, Chilcoat HD. Patterns of alcohol-dependence symptoms using a latent empirical approach: Associations with treatment usage and other correlates. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:870–878. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadley K, Clark CL, Caetano R. Couples’ drinking patterns, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related partnership problems. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madruga CS, Laranjeira R, Caetano R, Ribeiro W, Zaleski M, Pinsky I, Ferry CP. Early life exposure to violence and substance misuse in adulthood-The first Brazilian national survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AL. Latent class analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McKinney CM, Caetano R, Rodriguez LA, Okoro N. Does alcohol involvement increase the severity of intimate partner violence? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:655–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HB, Chen CM, Yi H-Y. DSM-IV criteria endorsement patterns in alcohol dependence: Relationship to severity. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:306–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, editor. Latent variable analysis: Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. Should substance use disorders be considered as categorical or dimensional? Addiction, 101, Supplement. 2006;1:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus users guide (Version 6) Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States: Main findings from the 2001– 2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). (NIH Publication No. 05–5737) Bethesda, MD: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CB, Heath AC, Kessler RC. Temporal progression of alcohol dependence symptoms in the U.S. household population: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:474–483. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol PE, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Investigating gender differences in alcohol problems: A latent trait modeling approach. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14:535–569. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary KD, Schumacher JA. The association between alcohol use and intimate partner violence: Linear effect, threshold effect, or both? Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1575–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plichta SB. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences: Policy and practice implications. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1296–1323. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees S, Silove D, Chey T, Ivancic L, Steel Z, Creamer,Forbes MD. Lifetime prevalence of gender-based violence in women and the relationship with mental disorders and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, McCutcheon VV, Pommer NE, Nelson EC, Duncan AE, Waldron M, Heath AC. Posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence in young women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:810–818. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon L, Logan TK, Cole J, Walker R. An examination of women's alcohol use and partner victimization experiences among women with protective orders. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008;43:1110–1128. doi: 10.1080/10826080801918155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Cavanaugh CE, Ufner MJ, Swan SC, Snow DL. Relationships among women's use of aggression, their victimization, and substance use problems: A test of the moderating effects of race/ethnicity. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2009;18:646–666. doi: 10.1080/10926770903103263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Leonard KE. Women's substance use and experiences of intimate partner violence: A longitudinal investigation among a community sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1649–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Sims L, Kingree JB, Windle M. Longitudinal associations between problem alcohol use and violent victimization in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM, Starzynski LL. Correlates of comorbid PTSD and drinking problems among sexual assault survivors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Schuck AM, White HR. An examination of pathways from childhood victimization to violence: The role of early aggression and problematic alcohol use. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:675–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack SC, Wilsnack RW. Drinking and problem drinking in US women. Patterns and recent trends. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 1995;12:29–60. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47138-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue QL, Bandeen-Roche K. Combining complete multivari-ate outcomes with incomplete covariate information: A latent class approach. Biometrics. 2002;58:110–120. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]