Abstract

Objectives

The authors investigated if a wireless system of call handling and task management for out of hours care could replace a standard pager-based system and improve markers of efficiency, patient safety and staff satisfaction.

Design

Prospective assessment using both quantitative and qualitative methods, including interviews with staff, a standard satisfaction questionnaire, independent observation, data extraction from work logs and incident reporting systems and analysis of hospital committee reports.

Setting

A large teaching hospital in the UK.

Participants

Hospital at night co-ordinators, clinical support workers and junior doctors handling approximately 10 000 tasks requested out of hours per month.

Outcome measures

Length of hospital stay, incidents reported, co-ordinator call logging activity, user satisfaction questionnaire, staff interviews.

Results

Users were more satisfied with the new system (satisfaction score 62/90 vs 82/90, p=0.0080). With the new system over 70 h/week of co-ordinator time was released, and there were fewer untoward incidents related to handover and medical response (OR=0.30, p=0.02). Broad clinical measures (cardiac arrest calls for peri-arrest situations and length of hospital stay) improved significantly in the areas covered by the new system.

Conclusions

The introduction of call handling software and mobile technology over a medical-grade wireless network improved staff satisfaction with the Hospital at Night system. Improvements in efficiency and information flow have been accompanied by a reduction in untoward incidents, length of stay and peri-arrest calls.

Article summary

Article focus

Can an out of hours wireless task requesting and tracking system improve quality and safety in secondary care?

Key messages

The widely adopted Hospital at Night system for out of hours working is inefficient and risks introducing error. We introduced a wireless task requesting and tracking system and showed this change was acceptable and improved qualitative and quantitative markers of efficiency and safety.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study showed clinically meaningful and statistically significant positive changes using a variety of complementary assessments. The study was observational and within a single acute NHS Trust.

Background

Care for patients in hospital is broadly divided into ‘in hours’, which comprises Monday to Friday between 09:00 and 17:00, and ‘out of hours’ (OOH), which comprises the remainder of the week and public holidays. Patients are therefore subject to OOH care for three-quarters of the year. OOH care in the NHS and many other systems is normally provided by junior staff with seniors supporting from home on request. Over the past decade, there has been both a reduction in junior doctors' working hours and an increase in the amount of clinical work both generally1 and OOH.2 Locally in Nottingham, we have seen yearly admissions rise by almost 25 000 (15%) between 1999–2000 and 2010–2011,3 while individual junior doctor's hours have fallen by more than 35% to comply with the European Working Time Directive. As a consequence of this directive, it became apparent that changes to the traditional on-call system were required to maintain patient safety. In response, the Hospital at Night (H@N) project was initiated and adopted nationally.4 Although the H@N solution is confined to the UK, the issue of maximising limited clinical resources OOH is common to almost all secondary healthcare systems and local solutions outside the UK share many of the same features. The issue also arises with non-medical staff, as other healthcare and support professionals such as radiographers or physiotherapists are usually fewer in number and cover a greater area than in normal working hours.

H@N projects intend to achieve safe clinical care using teams comprising junior doctors, nurses and clinical support workers to provide OOH cover. All requests for patient-related tasks from ward nurses are directed through a co-ordinator, usually a senior nurse, who provides a triage function and allocates tasks to team members. This national initiative is intended to deploy a co-ordinated team that improves efficiency in resource management, particularly allowing medical staff more time to engage in clinical activity. The exact composition of the team varies between hospitals dependent on the composition and volume of the workload and local policy, though all should be risk assessed using standard tools.5 An initial assessment of the impact of H@N implementation in 20054 suggested H@N was as safe as other forms of care. However, subsequent government reports showed both staff numbers and the ratio of staff per bed were higher following implementation of the H@N system.6 7

Assessment of the problem

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust serves 2.5 million people and employs over 13 000 staff managing 1700 beds. These beds are divided approximately equally across two sites, Queen's Medical Centre and Nottingham City Hospital (NCH). The H@N service at NCH for OOH care was introduced in 2006. As with most hospitals, H@N was based around a landline phone and pager system, with requests phoned from the ward to the coordinator and then passed onto the junior doctor or clinical assistant by phone. Two internal reports were conducted after informal concerns were raised over the H@N service,8 9 and their findings are summarised below:

As NCH covers 46.3 hectares and patients enter via eight different specialty admission points, locating the nearest phone was often time consuming for junior doctors who were in transit across the site. The number they responded to was also often engaged due to the volume of calls. This led to delays in calls being answered, and potential delay in clinical action being taken. The coordinator introduced as part of the national H@N initiative spent their shift answering and making phone calls from an office rather than providing senior nursing input. This repetitive role with minimal clinical contact had a negative impact on their morale. These frequent calls also interrupted clinical care provided by doctors and nurses, as they have been shown to do in other settings.10

It became apparent in Nottingham, as it did nationally, that the H@N service was limited by issues around task allocation and impaired communication between team members.8 The passing of clinical information from one team to another (handover) is a particular area of concern,11 12 is something junior doctors feel ill prepared to do13 and is frequently done rapidly and inaccurately.14 15

The H@N system also highlighted issues with transcription of information: Each junior made notes on loose paper when calls were received, and these were sometimes very brief because pressing clinical matters curtailed conversations. Should the paper be lost or damaged, or the information be noted inaccurately, basic details could be difficult and time consuming to reassemble. At the end of a shift, doctors often took their notes home rather than disposing of them as confidential waste or filing them in patient records, with attendant information governance issues. These issues have also been highlighted as sources of error outside the NHS.16 Verbal handover and hand-written records also led to a difficulty in assessing what actual work was being completed in each shift and by whom, meaning little information was available for workforce planning and feedback to in hours care regarding tasks that should have been completed during that period (eg, drug card rewrites, warfarin prescribing).

The installation of a Medical-Grade Network (Cisco Systems, San Jose, California, USA) across the University Hospitals Nottingham NHS Trust sites afforded the opportunity to introduce a secure wireless communications system for H@N. We worked with an industry collaborator (NerveCentre Software, Wokingham, UK) to design and implement a software system to promote efficiency and reduce risk within H@N. The software builds on components from the ‘borderless’ and ‘collaboration’ aspects of the Cisco network and the power and connectivity of the wired components.

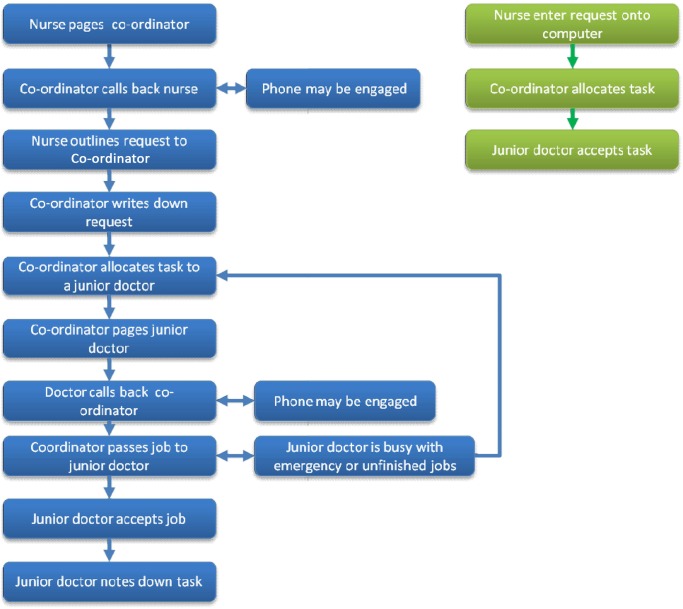

All tasks are now logged on to ward-based desktop PCs using the standardised and validated ‘SBAR’ (Situation–Background–Assessment–Recommendation) format17–19 recommended by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (http://www.institute.nhs.uk/). The task is then sent wirelessly to a co-ordinator who carries a small tablet PC weighing 0.5 kg. This task can then be triaged and allocated wirelessly to the most appropriate team member (the co-ordinator included). Tasks are relayed to junior doctors and support workers via a message to dedicated on-call mobile phones (see figure 1). The recipient accepts the task with a single button press and it is added to the freely accessible task list held on their phone. Once a task is passed to a junior doctor and accepted it stays active on both their and the co-ordinator's list until completion or reassignment to another individual. The system allows task prioritisation with jobs labelled as green, amber or red depending upon clinical need (see supplementary material). All ‘red’ tasks are copied to a phone carried by the middle grade doctor so they are aware of all potentially serious problems and can attend to assist or review as necessary. Pagers are now only carried by the cardiac arrest team as a fail-safe.

Figure 1.

Flow of information for one request under the two Hospital at Night systems.

We set out to assess the effect of the implementation of this new system on staff satisfaction, information flow and broad clinical outcomes.

Methods

We drew on the European Commission funded Model for Assessment of Telemedicine20 and the proposals of Westbrook and colleagues21 to inform our study methodology. This paper focuses on staff satisfaction and patient safety outcomes at NCH.

Review of untoward incidents

Two authors (DS and JDB) reviewed all clinical incidents that had been reported in accordance with the NHS policy via Datix software (Datix Ltd, London, UK) in the Medical Directorate over two periods of 2 months preceding (January and February 2011) and subsequent to (June and July 2011) the introduction of the new task allocation system. We chose these 2-month periods as the total number of reported incidents was identical. We selected the incidents that occurred OOH and were related to handover of information or job allocation. In the case of disagreement, arbitration was undertaken by a third author. The proportion of calls related to slow response of the H@N service or handover to or within the H@N service were compared by χ2 test. We acknowledge that incidents are traditionally under-reported in secondary care, and as such, the aim of this analysis was to ensure that the new system did not introduce any major new issues.

The number and directorate location (covered by H@N or not) of cardiac arrest calls placed at Nottingham City Hospital were recorded for a 6-month period (February to July) in 2010 prior to the introduction of H@N and for the equivalent period 1 year later. We recorded an ‘actual arrest’ where CPR or defibrillation or intubation was required as recorded on the Trust's standard cardiac arrest call audit form. ‘Urgent calls’ were those where assistance was required with an unwell patient. Three genuinely false calls requiring no medical intervention were discounted. The numbers of calls per month before and after the new system was introduced were compared by Mann–Whitney test.

Staff interviews and observation

To assess the overall impact of the new system on staff satisfaction, we undertook observation of, and non-directive interviews with, a purposive sample of H@N co-ordinators, junior doctors using the system, senior doctors, ward nursing staff and Trust management. A brief and flexible interview framework was agreed to elicit opinion and experiences regarding advantages or problems with the two systems for use OOH, information handover and the impact of the changes on the Trust generally. We also asked 20 users (five junior doctors, five co-ordinators, five ward nurses and five clinical support workers) selected in a quasi-random fashion (by day of week on shift) to complete a modified version of the IBM Computer System Usability Questionnaire22 before and after the introduction of NerveCentre software and wireless devices. These non-normally distributed paired data were analysed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

H@N co-ordinator activity

To assess the impact of the new system on the activity of the H@N co-ordinator, we recorded their activity for 1 week prior to its introduction (in March 2010) and again for a week 1 year later. The parameters recorded were the time spent by H@N co-ordinator on direct clinical care, the number of phone calls made and received, the time spent on logging and distributing tasks, the time spent giving telephone advice and the number of tasks assigned while away from their desk. The change in these parameters with the introduction of NerveCentre was assessed by t test.

Length of stay statistics

We assessed the weekly mean of lengths of stay for 6 months prior to the introduction of the new system (February to July 2010) and for the same 6 months in 2011 using centrally collated Trust statistics. The lengths of stay were compared by Mann–Whitney test.

Results

Review of untoward incidents

In both 2-month periods, there were 552 electronically reported incidents. Of these, the majority related to patients falls (see supplementary figures for a detailed breakdown). On systematic review of all 1104 incidents, we found 17 to be related to inadequate or absent handover or to a slow response of H@N, which resulted in actual patient harm or required remedial action to prevent this. Thirteen of these occurred prior to wireless working and four after its introduction. Exposure to wireless working was therefore associated with a reduction in the proportion of incidents that were attributable to the H@N system (OR=0.308, p=0.028 by χ2 test).

During the study periods, there was no change in the overall number of cardiac arrest calls placed at the NCH site (median 22.5 per month before and 21 after, p=0.973), though the total number of arrest calls for the Trust as a whole increased significantly (from 57.5 to 72 per month, p=0.041). In the initial 6 months, 26% of cardiac arrest calls placed within the area covered by H@N were to obtain help with patients who had not arrested. This proportion fell significantly to 11% after the new system was implemented (p=0.015).

Interviews

Three main themes repeatedly arose from the interviews and concerned the satisfaction of staff with the old H@N system, concerns over resource management and concerns over the accuracy of information transcription.

Satisfaction of staff with their role in the H@N system

All grades and professions reported a step change in their satisfaction with the H@N system. This was largely attributable to the facilitation of communication resulting in a marked increase in the time individuals spent undertaking tasks for which they felt they had been trained. The H@N co-ordinators felt this change most acutely, one saying simply:

“It has given me my job back” (H@N co-ordinator)

Other co-ordinators were similarly enthused to be released from overwhelming administrative duties:

“The system required you to be on the computer all the time. I didn't like that. I'm not a computer person; I'm a hands-on clinical person.” (H@N co-ordinator)

Many said that they were considering or actively seeking alternative employment before the new system was implemented:

“I wouldn't have stayed in this job if thing's hadn't changed. I would have left.” (H@N co-ordinator)

Frustration was not confined to the nursing staff, with middle grade doctors conveying their disenfranchisement with the H@N system, sometimes in explicit language not reproduced here.

“Initially we used to know what was going off [patients who are ill]. Hospital at Night put a barrier between the reg [middle grade] and the rest of hospital. Having the Blackberry [mobile phone] does make a difference. I can finally get hold of someone quickly to give advice or to let them know if I've got stuck on labour suite or somewhere.” (Middle grade)

Resource management

A recurring theme in the old system was that all pages that co-ordinators or junior doctors received appeared equally important until answered, and the process of answering pages from wards was time consuming. A co-ordinator explained she was often receiving pages faster than they could be answered, without knowing which to call back as a priority:

“(we) would write down the phone numbers and work through them one by one. For each number we would call the ward, and then bleep [page] the doctor…which could take ten minutes if the doctor was not near a phone or was busy.” (H@N co-ordinator)

It was also only by paging doctors or support workers that the co-ordinator could assess if they had completed their tasks, risking introducing additional delays.

“We had no idea when a doctor had completed a task or how long they are with a particular patient. If we page them we often take them away from the patient.” (H@N co-ordinator)

A ward sister commented that nurses placing bleeps grew frustrated with delays in obtaining a response and spent valuable time re-contacting the co-ordinator to ensure the task was treated appropriately:

“the efficiency of the new system, with nurses not needing to chase doctors, means nursing staff can spend more time with patients” (ward nurse)

Junior doctors were impressed at the reduction in time and inconvenience as the need to be bleeped greatly diminished. They also were relieved that their workload could be accurately monitored, improving the co-ordinators ability to distribute work evenly.

“I can easily contact the H@N co-ordinator, and she can see my outstanding workload at any time. It has taken away the worry that I'm leaving patients waiting.” (Junior doctor)

Senior doctors also had grown concerned with their inability to assess what actual work was being done by their juniors. Their perspective tended to be concern over potential medico-legal issues.

“Tasks range from the simple, rewriting a drug card, to the complicated, organizing a brain scan for a critically unwell unconscious adult at 4am…Our system did not accurately capture the breadth and depth of the complexities involved.” (Medical consultant)

The transcription of information

A major issue with the previous H@N system was the concern over the repeated verbal transfer of limited information. There was enthusiasm for the change in practice the new system has facilitated:

“It's great how the new system categorizes everything. It forces you to provide all the necessary information so that the doctor is properly prepared and turns up at the right place at the right time with the right patient details” (Ward sister)

Junior doctors expressed additional concerns over their own transcription of patient details when paged while busy, and their fear of losing their job list:

“I must have noted down the wrong name so I couldn't find the patient. I kept phoning the hospital at night co-ordinator but the phone was engaged so I just handed the job back at the end of the shift.” (Junior doctor)

“Love the fact that I don't need to carry paper around. There is no risk anymore that I'll lose my patient list” (Junior doctor).

As the H@N team is staffed by individuals in training posts, they are required to log the cases they see and the procedures they undertake. Few, if any, had time to prepare an anonymised second list to complement their job sheet. As a list of tasks they completed can now be emailed to each doctor at the end of the shift, this pressure has been removed.

“It was incredibly difficult to document the experience gained at night” (Junior Doctor)

Other comments that were repeated concerned the benefits in terms of reduced noise on the wards given the reduced need to make and receive phone calls and the great potential the project had for monitoring and planning OOH care in the future.

Satisfaction survey

Staff satisfaction with the H@N system itself improved significantly (p=0.008, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) from a median score of 62 (maximum possible =90) with the pager-based system to a median of 82 with the NerveCentre wireless technology system (see table 1). The minimum response score for each category improved markedly such that no-one recorded less than eight of 10 for their overall satisfaction with the system.

Table 1.

Comparative satisfaction of users of the old and new Hospital at Night (H@N) systems

| Statement | Old system |

New system |

||

| Median | Minimum | Median | Minimum | |

| Overall I am satisfied with how easy it is to use the system | 7 | 1 | 9 | 7 |

| It was easy to learn to use the system | 9 | 1 | 10 | 5 |

| The system takes little of my time allowing me to spend more time with patients | 6 | 1 | 10 | 7 |

| The system allows information on the patient to be accurately recorded | 5 | 0 | 10 | 7 |

| I feel comfortable using the system | 8 | 1 | 10 | 7 |

| Whenever I make a mistake using the system I recover quickly and without impact to safety | 8 | 1 | 9 | 7 |

| The organisation of information on the screens is clear | 6 | 1 | 9 | 7 |

| I like using the interface on this system | 6 | 0 | 9 | 5 |

| Overall, I am satisfied that the system effectively supports my job | 7 | 0 | 9 | 8 |

| Total Score (n) | 62 | 85 | ||

Scores are median values for 20 staff members (five junior doctors, five H@N co-ordinators, five clinical support workers and five ward nurses) for a modified version of the IBM Computer System Usability Questionnaire.22

H@N co-ordinator activity

Over the periods studied, the total number of tasks per shift assigned by the H@N co-ordinator did not differ significantly (weekly total 1280 vs 1379, comparison by tasks allocated per shift p=0.695). However, the number of tasks assigned to a team member while the co-ordinator was at their desk dropped sharply (weekly total 1280 vs 99, p<10−36). The time spent receiving and logging calls during each shift also fell markedly from a median (IQR) of 97% (4.32) of total shift time to 42% (27.47) of shift time (p<10−36). Commensurate to the decrease in time spent on the telephone and the ability to assign tasks away from their desks, co-ordinators were able to begin to engage in clinical care. Direct clinical care time increase from a baseline of zero to a median (IQR) of 56% (28.14) of shift time.

Length of stay statistics

The median length of stay on medical wards covered by NCH H@N was 6.50 days (n=839 in-patient stays) in the study period in 2010 and 5.67 days (n=739) in 2011 (p=0.004 by Mann–Whitney test). The median length of stay on other wards which were neither day-case units nor covered by NCH H@N was 2.90 days (n=1279 in-patient stays) in the study period in 2010 and 2.67 days (n=1254) in 2011 (p=0.263).

Discussion

In this study, we describe the implementation of a wireless system that allows task request, allocation and management on handheld devices for OOH care. Our evaluation of the new hardware and software reviewed aspects of patient safety, utilisation of resources and staff satisfaction by comparing operational processes before and after implementation.

The implementation of wireless working was extremely well received by all users with particular praise for the improvements in task-flow efficiency and information governance achieved. The H@N co-ordinators reported feeling liberated by the system and are spending vastly greater time engaged in direct clinical activity. A further marker of this is that long-standing vacancies for co-ordinator posts have now been filled. Although causality cannot be inferred, broad clinical measures such as length of stay and cardiac arrest calls placed for unwell patients fell significantly with the change in H@N system supporting at least clinical non-inferiority of new method.

Wireless systems similar to the one described here are not yet commonplace in secondary care in Europe, although limited computerised handover systems have shown the potential for patient benefit.23 24 Early adopters in other countries have seen improvements in clinical outcomes using a network to manage information passing within clinical teams and to track over pieces of equipment using radio-frequency identification tags25 26 and with electronic nursing records.27 Limited data on the use of push email to support current practise also exist.28 However, these initiatives tend to be adjuncts rather than replacements for current systems, and they are usually generic rather than tailored for purpose so do not include a standard data entry format with automatic population of fields and drop-down menus, and they do not automatically grade the urgency of communications.

Wireless technology also has the potential to allow advanced patient monitoring which can improve patient outcomes29 30 and save money.31 We also see potential for this system to collect data which will highlight wards where routine tasks are not completed in hours, to monitor the performance of different composition of OOH teams of junior doctors and to add clinical parameters to a dashboard of Trust performance. As the mobile devices are able to record the location of the users indoors and out, there is also scope for time and motion study to further increase efficiency. The wider applicability of an approach such as this to any group of individuals addressing complex and dynamic tasks with limited and geographically dispersed resources has also become apparent. Locally, portering and critical care outreach services have adopted a similar system for in-hours working, and it is being revised to manage personnel staffing emergency theatre lists and their liaison with ward nurses.

There is clearly a difficulty in assessing the impact of complex service delivery interventions such as the one described. It is practically extremely challenging to undertake a randomised trial of the system described as few centres have an appropriate network and it would require a considerable investment in equipment and staff training. Furthermore, one major flaw in the traditional pager system is its inability to accurately record activity. It is therefore difficult to assess the impact of the system at a ward or patient level as detailed information is only available post-introduction. We also acknowledge that we did not systematically record nurse and physician activity before and after implementation in the same way as was undertaken for the co-ordinators. Although the introduction of the new wireless working was associated with improvement in broad clinical measures, we also emphasise that this single centre observational study cannot prove causality. Future studies are needed to assess any benefits on patient safety or length of stay.

A major barrier to the implementation of this potentially highly productive system is cost, a factor influential in the design of H@N services nationally.32 The total cost of the software purchase and deployment across both Trust sites, and the additional hardware required for the project (40 phones for junior doctors and clinical support workers and four tablet computers for co-ordinators) was <£150 000. However, early indications are these costs will be offset relatively rapidly by the improved workforce planning facilitated by the system, by the reduction in delayed discharges or procedures and through fewer untoward incidents.

Wireless technology and securely held electronic data have become a central part of daily life outside the NHS. In this paper, we present an acceptable way of introducing such technology to address some of the issues common to H@N systems: we found it to be welcomed by users, efficient and be correlated with improved broad clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to Lizzie Poole, Michael Walker and Haydn Williams of Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust for facilitating data acquisition and to Paul Volkaerts of NerveCentre Software for revising the software to facilitate this project. We are grateful to the staff working out of hours: all those approached gave time for interviews, completion of questionnaires or allowed us to observe their activities throughout a shift.

Footnotes

To cite: Blakey JD, Guy D, Simpson C, et al. Multimodal observational assessment of quality and productivity benefits from the implementation of wireless technology for out of hours working. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000701. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000701

Contributors: DS, SC, PW, AF and JDB conceived of the ideas for study. DS, AF and JDB designed the study. DG, SC and PW undertook non-directive interviews and administered the questionnaires. CS collected and compiled data on cardiac arrest calls. AF and JDB acquired the clinical data. JDB, DES and DG reviewed the incident reports. JDB undertook the analyses. JDB and DES drafted the manuscript, which all authors critically reviewed and contributed to revising before submission.

Funding: This project was funded by Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, with salary contributions from the National Institute of Health Research (JDB), the University of Nottingham (DS), Cisco Systems (PW) and the Association of Certified Chartered Accountants (SC).

Competing interests: PW is employed by the manufacturer of the medical-grade network used in this study (Cisco Systems). The other authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The commercial entities Cisco Systems and NerveCentre Software had no role in the design and execution of analyses and were not permitted access to analyse task or patient identifiable data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Supplementary data are available as indicated in the body of the manuscript. Any task or event-level data contain information regarding the care of individual patients and as such detailed records remain confidential.

References

- 1.Peacock PJ, Peacock JL, Victor CR, et al. Changes in the emergency workload of the London Ambulance Service between 1989 and 1999. Emerg Med J 2005;22:56–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson C, Hayhurst C, Boyle A. How have changes to out-of-hours primary care services since 2004 affected emergency department attendances at a UK District General Hospital? A longitudinal study. Emerg Med J 2010;27:22–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HESOnline: Hospital Episode Statistics. NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahon A, Harris C, Tyrer J, et al. The Implementation and Impact of Hospital at Night Projects. In: Department of Health , ed. London: Crown, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 5.NPSA Hospital at Night—Patient Safety Risk Assessment Guide. Department of Health, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS Workforce Projects Model Hospital at Night Team: 2007 Survey Findings. Department of Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS Workforce Projects The Case for Hospital at Night —The Search for Evidence. Department of Health, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teahon K. Report on a Study of May 2009. Medical Out of Hours Service City Campus. University Hosptials Nottingham NHS Trust, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace S, McKinnin S, Guy D. External Review of Hospital at Night. Medical Out of Hours Service City Campus. University Hosptials Nottingham NHS Trust, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz MH, Schroeder SA. The sounds of the hospital. Paging patterns in three teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1585–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bywaters E, Calvert S, Eccles S, et al. Safe Handover: Safe Patients. British Medical Association, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabol LI, Andersen ML, Ostergaard D, et al. Descriptions of verbal communication errors between staff. An analysis of 84 root cause analysis-reports from Danish hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf 2011;20:268–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleland JA, Ross S, Miller SC, et al. “There is a chain of Chinese whispers”: empirical data support the call to formally teach handover to prequalification doctors. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:267–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokode M, O'Riordan B, Barthelmes L. “That's all I got handed over”: missed opportunities and opportunity for near misses in Wales. BMJ 2006;332:610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sithamparanathan M. Personal views—“That's all I got handed over”. BMJ 2006;332:496–96 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Volpp KG, Grande D. Residents' suggestions for reducing errors in teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med 2003;348:851–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haig KM, Sutton S, Whittington J. SBAR: a shared mental model for improving communication between clinicians. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:167–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohenhaus S, Powell S, Hohenhaus J. Enhancing patient safety during hand-offs: standardized communication and teamwork using the 'SBAR' method. Am J Nurs 2006;106:72A–72B16481861 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckett CD, Kipnis G. Collaborative communication: integrating SBAR to improve quality/patient safety outcomes. J Healthc Qual 2009;31:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidholm K, Bowes A, Dyrehauge S, et al. The MAST Manual: Model for Assessment of Telemedicine. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J, Iedema R, et al. Evaluating the impact of information communication technologies on complex organizational systems: a multi-disciplinary, multi-method framework. In: Fieschi M, ed. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2004:1323–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis JR. IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires—psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. Int J Hum Comput Interact 1995;7:57–78 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raptis DA, Fernandes C, Chua W, et al. Electronic software significantly improves quality of handover in a London teaching hospital. Health Inform J 2009;15:191–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan S, O'Riordan JM, Tierney S, et al. Impact of a new electronic handover system in surgery. Int J Surg 2011;9:217–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.HIAE Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein Protocols. Sao Paolo, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cisco-Systems Brazilian Hospital Deploys Innovative Services. MGN Consumer Case Studies. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindgren CL, Elie LG, Vidal EC, et al. Transforming to a computerized system for nursing care organizational success within magnet idealism. Comput Inform Nurs 2010;28:74–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor C, Friedrich JO, Scales DC, et al. The use of wireless e-mail to improve healthcare team communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2009;16:705–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:658–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lilly CM, Cody S, Zhao H, et al. Hospital mortality, length of stay, and preventable complications among critically ill patients before and after tele-ICU reengineering of critical care processes. JAMA 2011;305:2175–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong JR, Sirio CA, Rotondi AJ. eICU program favorably affects clinical and economic outcomes. Crit Care 2005;9:E22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hospital at Night Baseline Report. NHS, 2006 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.