Abstract

Objectives

Universally offered child health reviews form the backbone of the UK child health programme. The reviews assess children's health, development and well-being and facilitate access to additional support as required. The number of reviews offered per child has been reduced over recent years to allow more flexible provision of support to families in need: equitable coverage of the remaining reviews is therefore particularly important. This study assessed the coverage of universal child health reviews, with an emphasis on trends over time and inequalities in coverage by deprivation.

Design

Assessment of the coverage of child health reviews by area-based deprivation using routinely available data. Supplementary audit of the quality of the routine data source used.

Setting

Scotland.

Participants

Two cohorts of around 40 000 children each. The cohorts were born in 1998/1999 and 2007/2008 and eligible for the previous programme of five and the current programme of two preschool reviews, respectively.

Outcome measures

Coverage of the specified child health reviews for the whole cohorts and by deprivation.

Results

Coverage of the 10 day review is high (99%), but it progressively declines for reviews at older ages (86% for the 39–42 month review). Coverage is lower in children living in the most deprived areas for all reviews, and the discrepancy progressively increases for reviews at older ages (78% and 92% coverage for the 39–42 month review in most and least deprived groups). Coverage has been stable over time: it has not increased for the remaining reviews after reduction in the number of reviews provided.

Conclusions

The inverse care law continues to operate in relation to ‘universal’ child health reviews. Equitable uptake of reviews is important to ensure maximum likely impact on inequalities in children's outcomes.

Article summary

Article focus

A series of universally offered child health reviews providing assessment of children's health, development and well-being forms the backbone of the UK child health programme.

The number of reviews offered per child has been reduced over recent years to increase capacity to provide effective individualised support to families in need: equitable coverage of the remaining reviews is therefore particularly important.

We used routinely available data to assess the coverage of the various child health reviews (overall and by deprivation) before and after the change in the number of reviews offered.

Key messages

Coverage of reviews offered in early infancy is high, but it progressively declines for reviews at older ages (around 99% coverage for the 10 day review and 86% for the 39–42 month review).

Coverage is lower in the most deprived groups for all reviews, and the discrepancy progressively increases for reviews at older ages (78% and 92% coverage for the 39–42 month review in most and least deprived groups).

Coverage has not changed for the remaining reviews after reduction in the number of reviews offered: the inverse care law continues to operate in relation to provision of ‘universal’ child health reviews.

Strengths and limitations of this study

To our knowledge, no quantitative assessment of the coverage of child health reviews offered in the UK has previously been published.

This analysis involved large numbers of children: over 80 000 children eligible to receive their child health reviews in Scotland were included.

Careful consideration must be given to data quality when analysing routinely available data: we conducted an audit of data quality to allow the uncertainty in the results to be quantified.

Introduction

Children's early experiences profoundly shape their development and long-term health and well-being.1 2 The UK child health promotion programme aims to support children through their early years and help them attain their developmental and health potential.3 4 The programme comprises screening, immunisation, developmental reviews, parental support and health promotion. A number of reviews are offered to all children at specified ages. The reviews are usually carried out by health visitors (HVs), sometimes alongside others such as general practitioners (GPs), and focus on assessing children's growth, development, health and wider family well-being and thus determining the need for further professional input.

Professional guidance on the delivery of the child health programme issued in 20035 suggested that there was too much emphasis on provision of these ‘routine’ reviews leading to a relatively inflexible system that had done little to address persistent inequalities in children's outcomes.6 Adoption of this guidance across the UK has led to a new emphasis on a ‘progressive universalism’ model of delivery, with a reduced programme of universal reviews complemented by more intensive individualised care for those families in need of professional services.7

The Scottish Government took particularly decisive action in this regard. Policy issued in 2005 reduced the number of universal preschool child health reviews from six (at 10 days, 6–8 weeks, and 8–9, 22–24, 39–42 and 48–54 months) to two (at 10 days and 6–8 weeks).8 At the same time, a three-category indicator of need (the Health Plan Indicator—core, additional and intensive) was introduced to facilitate the identification of those children requiring enhanced support in addition to that offered through the universal programme. The revised programme was implemented in different NHS board areas between 2005 and 2010.

People who are most in need of health services are often the least likely to access them.9 People from deprived areas are particularly disadvantaged in terms of access to preventive/proactive healthcare.10 11 There is evidence from the USA of marked inequalities in uptake of ‘well child’ care,12–14 but, to our knowledge, no information on inequalities in uptake of child health reviews in the UK has been published to date. Ambivalence towards, or disinclination to engage with, the child health programme has been documented, however, particularly among families from deprived areas.15–18

For the programme to contribute to reducing inequalities in children's outcomes, it is essential that children from across the social spectrum participate in the universal reviews and hence have the opportunity to receive the level of input required to secure good outcomes. We therefore used routine Scottish data to explore the following questions:

What proportion of children actually receives the universal child health reviews?

How does review coverage vary by deprivation?

How has (inequality in) review coverage changed over time, in particular before and after the reduction in number of reviews offered?

We also audited the quality of the relevant routine data to provide additional information not previously available.

Methods

Routine data sources used

All children in Scotland have a record created in the child health programme national information system. One element of the system, Child Health Surveillance Programme—PreSchool (CHSP-PS), administers the child health reviews offered to preschool children.19 When a child is due for a review, CHSP-PS sends an appointment to the family and the appropriate paper review form (in triplicate) to the HV. After the review, one copy of the completed form is returned to the local child health department where administrative staff enter the findings into the CHSP-PS system; one copy is retained in the child's HV notes and the third copy is inserted into the child's parent held record. The NHS Information Services Division (ISD) receives quarterly downloads from the system for analytical purposes.

Child health reviews included

Table 1 shows the reviews offered to all children in Scotland before and after implementation of the 2005 policy that are included in this study. It was not mandatory to record provision of the old 48–54 month review on CHSP-PS (a situation that reflects a historical decision) hence that review has been excluded. HVs are solely responsible for provision of the 10 day review. The 6–8 week review usually involves an initial assessment by the HV, followed by a medical examination by the GP. GP input into provision of reviews at older ages varied.

Table 1.

Cohorts included in the analysis

| Cohort | Date of birth range | Included child health reviews |

Date of CHSP-PS extract used in analysis | |

| Review name | Upper age limit by which the review should be completed | |||

| Old child health programme | 1 November 1998–31 October 1999 | 10 day | None specified | November 2003 |

| 6–8 week | 12 weeks | |||

| 8–9 month | 10 months | |||

| 22–24 month | 26 months | |||

| 39–42 month | 44 months | |||

| New child health programme | 1 July 2007–30 June 2008 | 10 day | 28 days | February 2009 |

| 6–8 week | 12 weeks | |||

CHSP-PS, Child Health Surveillance Programme—PreSchool.

Cohorts included in study

Table 1 also shows the two cohorts that were studied. The ‘old child health programme’ cohort had the opportunity to receive all five previously offered reviews, whereas the ‘new child health programme’ cohort had the opportunity to receive the current reduced programme of two reviews. Children who were consistently registered to receive their child health programme in selected NHS board areas from birth up to the date of the relevant CHSP-PS data extracts were included. Boards that were established users of the CHSP-PS system by November 1998 and had implemented the revised child health programme by the beginning of 2007 were selected. These were Argyll and Clyde, Ayrshire and Arran, Borders, Fife, Forth Valley, Greater Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Lothian and Tayside. These areas together contain around 82% of the Scottish population aged younger than 5 years. The CHSP-PS downloads taken around 4 months after the upper age at which the children should have had the last included review were used for analysis.

Assessing coverage of universally offered child health reviews

All included children in each cohort were identified. Their postcode of residence at the time of data extract was used to derive their 2006 Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile and whether they lived in one of the 15% most or least deprived areas of Scotland.20 Whether the children had a record on CHSP-PS of receiving each of the relevant reviews was then noted. Whether they received their reviews below the recommended upper age limit21 (see table 1) was also noted for all reviews except the 10 day review as the age of the child at this review is incompletely recorded. Coverage of the various reviews (at any age or where possible within the recommended age range) by deprivation level was calculated.

Differences in coverage were assessed by χ2 tests with Yates' continuity correction.22 CIs for differences in coverage between least and most deprived groups were calculated using the Newcombe–Wilson formula.23 Finally, the total number of registered births occurring within the corresponding date ranges and NHS board areas was noted to assess the number of children excluded due to dying or moving over the period of study.

Audit of CHSP-PS data quality

Due to the way the CHSP-PS system works, it may be that some children with no CHSP-PS record of a review did actually receive their review, but the paper form went astray prior to data entry. To quantify this potential for underestimation of review coverage, we conducted an audit of CHSP-PS data.

ISD prepared a case listing of all children from the new child health programme cohort that were registered with a GP practice in two localities as at February 2010 who had no CHSP-PS record of receiving a 10 day and/or a 6–8 week review. The two localities (in Greater Glasgow and Fife) were selected as they both had review coverage rates similar to that seen for Scotland as a whole, included a range of deprived/affluent and urban/rural areas, and had HV managers who were enthusiastic to undertake the audit.

Individual audit forms for all children on the case listings were securely transferred to the relevant HV teams. The forms asked whether the apparently missing review had in fact been received and then either why it had been missed or why no record was available on CHSP-PS as appropriate. The HVs completed the forms after reviewing the children's contemporaneous clinical notes. All audit returns were entered into SPSS V. 17.0. Two authors (AS and RW) agreed on appropriate coding of free text fields. Additional variables derived from the children's overall child health programme electronic records, specifically the child's sex, deprivation quintile and most recently recorded Health Plan Indicator category were merged into the analysis file. The resulting data were analysed using simple descriptive statistics.

Results

Coverage of universally offered child health reviews

The number of children included in each cohort is shown in table 2. The proportion of children born in the relevant board areas that were excluded from the analysis is higher for the old child health programme cohort as these children had to remain resident in the same board area for a longer period to be included. The proportion of children with an unknown deprivation category was low in both cohorts.

Table 2.

Number of children in each cohort

| Cohort | Total number of births in included boards in relevant date range | Number (%) of children included in cohort | Number (%) of children in cohort with known deprivation status |

| Old child health programme | 45 122 | 37 668 (83.5) | 37 325 (99.1) |

| New child health programme | 48 310 | 45 777 (94.8) | 45 624 (99.7) |

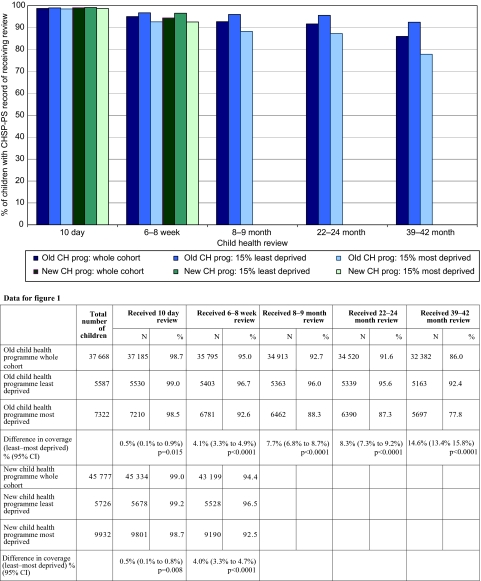

The proportion of children in each cohort that had a CHSP-PS record of receiving the various child health reviews is shown in figure 1. In the old child health programme cohort, coverage declined for each subsequent review: 98.7% and 86.0% of children had a record of receiving their 10 day and 39–42 month reviews, respectively. For each review, children living in the most deprived areas were significantly less likely to have a record of receiving the review than those living in the least deprived areas. The absolute difference in review coverage between deprived and affluent areas increased for each subsequent review: for example, 77.8% and 92.4% of children from the most and least deprived areas had a record of receiving their 39–42 month review, respectively (difference of 14.6%, 95% CI 13.4% to 15.8%, p<0.0001). Coverage of the 10 day and 6–8 week reviews was very similar for the new child health programme cohort to that seen for the earlier cohort. The degree of inequality in coverage of these reviews also remained unchanged.

Figure 1.

Coverage of universally offered child health reviews. Least and most deprived groups are children living in the 15% least and most deprived areas of Scotland, respectively. CH, child health; CHSP-PS, Child Health Surveillance Programme—PreSchool.

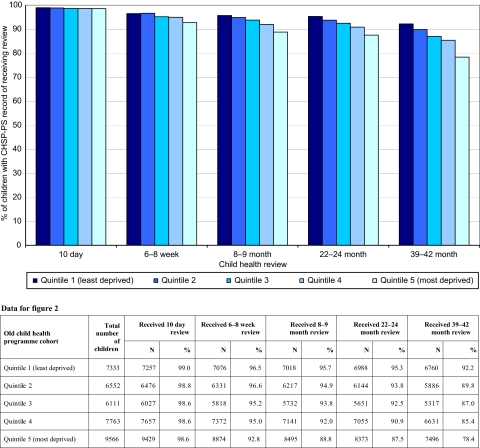

When coverage was assessed for all deprivation quintiles rather than just the least and most deprived groups, a clear deprivation gradient was found for all reviews except the 10 day review for each cohort (figure 2). Coverage of the 10 day review was very high for both cohorts, and although the most deprived quintile always had lower coverage than the least deprived quintile, no clear gradient was evident for the intermediate deprivation groups.

Figure 2.

Coverage of universally offered child health reviews by deprivation quintile (old child health programme cohort for illustration). CHSP-PS, Child Health Surveillance Programme—PreSchool.

When only reviews conducted within the recommended age limit were included, overall coverage reduced by between 3.0% and 5.6%. Children from deprived areas were consistently more likely to have their reviews late hence inequalities in coverage of timely reviews were particularly wide. In the new child health programme cohort, 93.8% of children from the least deprived areas had a record of receiving a 6–8 week review before 12 weeks of age (96.5% at any age) compared with 87.8% of children from the most deprived areas (92.5% at any age).

Audit of CHSP-PS data

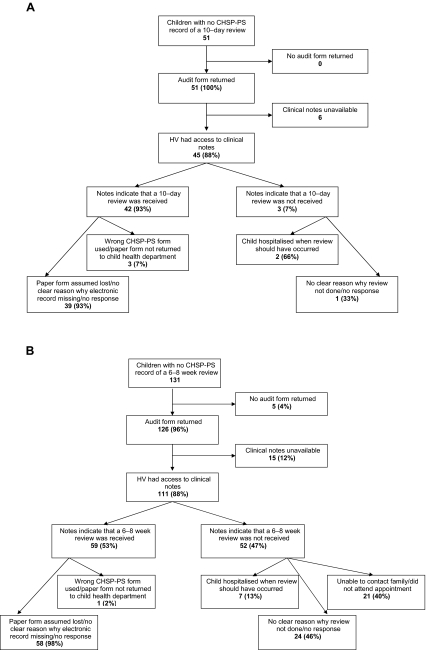

A total of 2784 children were resident in the two audit areas and eligible for inclusion: 51 (1.8%) had no CHSP-PS record of a 10 day review and 131 (4.7%) had no record of a 6–8 week review. Six children were in both categories; hence, a total of 182 missing reviews for 176 children were included in the audit. The audit results are summarised in figure 3. A very high rate of return (177/182, 97%) was achieved, and in the large majority of cases (156/177, 88%), the child's clinical notes had been available to the HV, hence the returned form was informative.

Figure 3.

Results of audit of Child Health Surveillance Programme—PreSchool (CHSP-PS) data. (A) Children with no CHSP-PS record of a 10 day review. (B) Children with no CHSP-PS record of a 6–8 week review. HV, health visitor.

For 42 of the 45 (93%) children with no CHSP-PS record of a 10 day review (and who had an informative audit return), the clinical notes indicated that a review had actually taken place. By contrast, a review had only been provided to 59 of the 111 (53%) children with no record of a 6–8 week review. For 21 of the 52 (40%) children who had genuinely missed their 6–8 week review, the HV specifically indicated that this was due to being unable to contact the family or the family repeatedly not attending appointments. In a further seven (13%) cases, the review was not provided due to the child being in hospital.

There was a clear tendency for children who genuinely missed their 6–8 week review (compared with those who received the review but had no CHSP-PS record) to have higher needs. For example, 41/52 (79%) of the children who missed their review lived in one of the two most deprived quintile areas compared with 23/59 (39%) of the children who did receive the review. Similarly, 35/52 (67%) of children who missed their review had ‘additional’ or ‘intensive’ as the most recently recorded Health Plan Indicator category on their overall child health programme electronic record compared with 20/59 (34%) of children who received their review.

HVs were asked whether they had had any contact with the children who genuinely missed their 6–8 week review when the children were aged between 4 and 12 weeks: in 45/52 (87%) cases, the HV indicated they had had at least one face-to-face or telephone contact with the child or parents; in four cases, the HV indicated they had had no contact at all (and in all cases, this was ascribed to the child being in hospital), and no response was provided in three cases.

Discussion

This analysis of routinely available data shows that not all children who are offered ‘universal’ child health reviews actually receive them. Coverage of the 10 day review is very high, but it declines for each subsequent review. The ‘inverse care law’9 applies to coverage of child health reviews: children from more deprived areas are less likely to receive their reviews and the inequalities are wider for reviews offered at older ages. The level of inequality in coverage has been stable over time and (for the remaining reviews) has not changed following the implementation of a new child health programme offering a much reduced number of reviews.

A further two cohorts were examined to confirm the consistency of the findings. One cohort of children born November 2000 to October 2001 that had the opportunity to receive the old child health programme immediately before it was withdrawn and one born April 2006 to July 2006 who received the revised programme immediately after its implementation: (inequalities in) review coverage was very similar for these cohorts.

We recognise that our analysis is restricted to children who remained resident in the same NHS board area for the period of study, that is, up to 59 months of age for the old child health programme cohort and up to 18 months for the new cohort. A previous unpublished analysis conducted by ISD found that the coverage of child health reviews experienced by children who remain in the same NHS board area throughout childhood is marginally, but not significantly, higher than that experienced by children who move between board areas. Coverage of child health reviews for children who emigrate out of Scotland altogether is unknown, but emigration is commoner among least deprived groups. Our results are therefore likely to provide a reasonable estimate of the child health review coverage in the whole Scottish population.

The audit of CHSP-PS data provides valuable information on the reliability of the findings. The audit shows that the reliance on transfer of paper forms before data entry does result in some data loss. The actual level of review coverage is therefore likely to be somewhat higher than the results suggest. For example, the overall percentage of children missing their 6–8 week review is likely to be closer to 2.5% than 5%. The general patterns observed are very likely to be real, however. Indeed, the audit findings emphasise the association between missing child health reviews and greater vulnerability: the level of inequality in review coverage may therefore actually be wider than that presented.

For children born after the implementation of the revised child health programme, it has obviously only been possible to examine the coverage of the two remaining reviews, both of which are offered in early infancy. Implementation of the revised review schedule aimed to strengthen the programme's ability to consistently reach children in need of support, provide effective early intervention and thus reduce inequalities in children's outcomes.8 One would therefore have hoped and expected to see reduced inequality in coverage for the remaining reviews. The finding that there has been no change is disappointing.

It appears that a minority of families (with relatively high needs) continue to miss out on their child health reviews. This analysis cannot fully explain why children miss their reviews, but the audit results suggest that unavailability (eg, child in hospital) or parental disengagement (eg, failure to respond to multiple invitations) are the most common underlying reasons. The audit results provide reassurance that almost all children who genuinely missed their 6–8 week review had some kind of contact with their HV, however, indicating that few if any children are completely unknown to services. Further qualitative work with HVs and parents will be required to more fully understand why some families do not participate in child health reviews and to develop innovative services that meet their needs. There has been a significant reduction in inequalities in breastfeeding rates in Scotland over recent years (driven mainly by increasing rates in more deprived groups),24 giving cause for optimism that child health promotion activities can effectively engage deprived groups and reduce inequalities. Work looking at facilitation of, and barriers to, engagement of families in other child well-being services such as Sure Start may also hold valuable lessons for the child health programme.25–27 There is evidence that the distribution of HV resources are not always adequate for, or aligned with, population needs. Achieving equitable coverage of child health reviews will therefore also require careful consideration of the HV resources available in different areas.28–30

There has been debate in Scotland recently as to whether the core programme of universal child health reviews has been reduced too far. HVs have expressed unease at the lack of a ‘safety net’ opportunity for reassessment of children's needs after early infancy. The Scottish Government therefore issued guidance in early 2011 recommending a further review at 24–30 months of age,31 although this is yet to be fully implemented. It will be particularly important to strive for equitable coverage of this new review in light of the historical results presented here that show marked inequalities in uptake of reviews in this age group.

In England, despite an established policy to review all children at 24–30 months, there are still only 60% of Primary Care Trusts commissioning this.32 A robust universal service is essential on which to base targeted professional input, but this is not being uniformly achieved. It is clear that children who do not attend their child health reviews are likely to have relatively high needs, and robust efforts should be made to assess their needs and engage them and their families with appropriate and sensitive services. It will remain important to monitor the coverage of universal child health reviews as an indicator of the performance of the child health programme and its likely impact on inequalities in children's outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the HV managers and practitioners who contributed to the audit of CHSP-PS data, in particular Cathy Holden and Lorraine Ronalson, and to Heather Graveson for inputting audit results. We are also grateful to Harry Campbell and Sarah Cunningham-Burley for guidance and comments.

Footnotes

To cite: Wood R, Stirling A, Nolan C, et al. Trends in the coverage of ‘universal’ child health reviews: observational study using routinely available data. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000759. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000759

Funding: RW undertook this work while in receipt of a Clinical Academic Fellowship from the Scottish Government's Chief Scientist Office (CAF/06/05). Study design, conduct and reporting were independent of funders at all times.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was not required for this study. Information Services Division staff adhered to NHS National Services Scotland Confidentiality Guidelines at all times when handling patient data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The routine data analysed for this study are held by NHS National Services Scotland Information Services Division (http://www.isdscotland.org/).

References

- 1.Shore R. Rethinking the Brain: New Insights into Early Development. New York: New York Families and Work Institute, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin LG, Siddiqi A, Hertzman C. Early Child Development: A Powerful Equalizer. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Human Early Learning Partnership, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair M, Hall D. From health surveillance to health promotion: the changing focus in preventive children's services. Arch Dis Child 2006;91:730–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair M. Promoting children's health. Paediatr Child Health 2010;20:174–8 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall DMB, Elliman D. Health for All Children. 4th edn Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer N. European Society for Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ESSOP) position statement. Social inequalities in child health—towards equity and social justice in child health outcomes. Child Care Health Dev 2008;34:631–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health The Child Health Promotion Programme. Pregnancy and the First Five Years of Life. London: UK Government, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scottish Executive Health for All Children 4: Guidance on Implementation in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tudor Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;297:405–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goddard M, Smith P. Equity of access to health care services: theory and evidence from the UK. Soc Sci Med 2001;53:1149–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acheson D. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report. London: The Stationery Office, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ronsaville DS, Hakim RB. Well child care in the United States: racial differences in compliance with guidelines. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1436–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu SM, Bellamy HA, Kogan MD, et al. Factors that influence receipt of recommended preventive pediatric health and dental care. Pediatrics 2002;110:e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung PJ, Lee TC, Morrison JL, et al. Preventive care for children in the United States: quality and barriers. Annu Rev Public Health 2006;27:491–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray L, Woolgar M, Murray J, et al. Self-exclusion from health care in women at high risk for postpartum depression. J Public Health Med 2003;25:131–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roche B, Cowley S, Salt N, et al. Reassurance or judgement? Parents' views on the delivery of child health surveillance programmes. Fam Pract 2005;22:507–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karmali J, Madeley RJ. Mothers' attitudes to a child health clinic in a deprived area of Nottingham. Public Health 1986;100:156–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyle G. Parents' view of child health surveillance. Health Educ J 1993;52:42–4 [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Child-Health/Child-Health-Programme/Child-Health-Systems-Programme-Pre-School.asp (accessed 7 Oct 2011).

- 20.Scottish Executive Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2006: General Report. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive, 2006. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/SIMD (accessed 7 Oct 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21.NHS Scotland Child Health Surveillance Programme Pre-school: Clinical Guidelines. Edinburgh: NHS Scotland, 2010. http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Child-Health/Child-Health-Programme/PS_clinical_guidelines_oct10.pdf (accessed 7 Oct 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 22.http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/Contingency1.cfm (accessed 7 Oct 2011).

- 23.http://faculty.vassar.edu/lowry/VassarStats.html (accessed 7 Oct 2011).

- 24.http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Child-Health/Infant-Feeding/ (accessed 27 Oct 2011).

- 25.Coe C, Gibson A, Spencer N, et al. Sure start: voices of the ‘hard-to-reach'. Child Care Health Dev 2008;34:447–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northrop M, Pittam G, Caan W. The expectations of families and patterns of participation in a Trailblazer Sure Start. Community Pract 2008;81:24–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lever M, Moore J. Home visiting and child health surveillance attendance. Community Pract 2005;78:246–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crofts DJ, Bowns IR, Williams TS, et al. Hitting the target: the equitable distribution of health visitors across caseloads. J Public Health Med 2000;22:295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steel N, Reading R, Allen C. An assessment of need for health visiting in general practice populations. J Public Health Med 2001;23:121–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cowley S. A funding model for health visiting (part 1): baseline requirements. Community Pract 2007;80:18–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scottish Government A New Look at Hall 4-the Early Years—Good Health for Every Child. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32.http://www.childrensmapping.org.uk/topics/healthychild/ (accessed 7 Oct 2011).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.