Abstract

Background: Increased consumption of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω3-PUFAs) from fish oil (FO) may have cardioprotective effects during ischemia/reperfusion, hypertrophy, and heart failure (HF). The cardiac Na+/H+-exchanger (NHE-1) is a key mediator for these detrimental cardiac conditions. Consequently, chronic NHE-1 inhibition appears to be a promising pharmacological tool for prevention and treatment. Acute application of the FO ω3-PUFAs eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) inhibit the NHE-1 in isolated cardiomyocytes. We studied the effects of a diet enriched with ω3-PUFAs on the NHE-1 activity in healthy rabbits and in a rabbit model of HF induced by volume- and pressure-overload. Methods: Rabbits were allocated to four groups. The first two groups consisted of healthy rabbits, which were fed either a diet containing 1.25% (w/w) FO (ω3-PUFAs), or 1.25% high-oleic sunflower oil (ω9-MUFAs) as control. The second two groups were also allocated to either a diet containing ω3-PUFAs or ω9-MUFAs, but underwent volume- and pressure-overload to induce HF. Ventricular myocytes were isolated by enzymatic dissociation and used for intracellular pH (pHi) and patch-clamp measurements. NHE-1 activity was measured in HEPES-buffered conditions as recovery rate from acidosis due to ammonium prepulses. Results: In healthy rabbits, NHE-1 activity in ω9-MUFAs and ω3-PUFAs myocytes was not significantly different. Volume- and pressure-overload in rabbits increased the NHE-1 activity in ω9-MUFAs myocytes, but not in ω3-PUFAs myocytes, resulting in a significantly lower NHE-1 activity in myocytes of ω3-PUFA fed HF rabbits. The susceptibility to induced delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs), a cellular mechanism of arrhythmias, was lower in myocytes of HF animals fed ω3-PUFAs compared to myocytes of HF animals fed ω9-MUFAs. In our rabbit HF model, the degree of hypertrophy was similar in the ω3-PUFAs group compared to the ω9-MUFAs group. Conclusion: Dietary ω3-PUFAs from FO suppress upregulation of the NHE-1 activity and lower the incidence of DADs in our rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload.

Keywords: Na+/H+-exchanger, pHi, fish oil, diet, heart failure, hypertrophy, arrhythmias

Introduction

Increased consumption of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω3-PUFAs) from fish oil (FO) may exert beneficial effects on the heart, as evidenced by a decreased risk of ischemic heart disease, sudden cardiac death (Burr et al., 1989; GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators, 1999), and a lower incidence of heart failure (HF; Mozaffarian et al., 2005; Yamagishi et al., 2008; Levitan et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2011). Various mechanisms for the observed beneficial effects of ω3-PUFAs have been proposed, i.e., decrease in blood pressure, heart rate, and platelet aggregation, anti-inflammatory (Kris-Etherton et al., 2002), and ionic remodeling resulting in a decrease of cardiac arrhythmias (den Ruijter et al., 2007; London et al., 2007), but the exact mechanisms are not fully known.

Evidence is increasing that the Na+/H+-exchanger isoform-1 (NHE-1) plays a crucial role in ischemia/reperfusion injury, hypertrophy, and HF (for reviews, see Cingolani and Ennis, 2007; Fliegel, 2009; Vaughan-Jones et al., 2009). The NHE-1 is an integral membrane protein that extrudes one H+ ion in exchange for one Na+ ion in an electroneutral fashion. Its activity is high at acidic intracellular pH (pHi) conditions and gradually declines to zero when its set-point pHi value, just above resting pHi value (∼pH 7.2) is reached. At resting pHi acid extrusion through NHE-1 activity equals acid loading activity and proton production rate, thereby maintaining pHi at neutral values. This, however, is at the expense of a continuous Na+ influx. Thus, the NHE-1 has also a major role in intracellular Na+ ([Na+]i) loading (Baartscheer and van Borren, 2008; Fliegel, 2009; Vaughan-Jones et al., 2009). This [Na+]i loading effect is of importance especially under conditions where NHE-1 activity is high such as ischemia/reperfusion (Ayoub et al., 2003; Bak and Ingwall, 2003; van Borren et al., 2004), hypertrophy, and HF (Baartscheer et al., 2003a; Chahine et al., 2005; van Borren et al., 2006; Nakamura et al., 2008). In these conditions, the [Na+]i loading via the NHE-1 shifts the driving force of Na+/Ca2+ exchange into the direction of less forward and increased reversed modes, which consequently will elevate intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) concentration with potentially detrimental cardiac effects. Consequently, a reduction of Na+ influx via NHE-1 inhibition appears to be a promising pharmacological tool for the treatment of ischemia/reperfusion, hypertrophy, and HF (Baartscheer et al., 2005; Cingolani and Ennis, 2007).

Goel et al. (2002) have shown that acute application of the ω3-PUFA eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) as well as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) inhibited the NHE-1 in isolated cardiomyocytes. Considering the importance of NHE-1 in ischemia/reperfusion injury, hypertrophy, and HF, NHE-1 inhibition may be the crucial link between FO and the well-known cardioprotective effects of ω3-PUFAs. In addition, it suggests that ω3-PUFAs may be an alternative or a complementary approach to existing NHE-1 inhibiting pharmacological drugs. In the present study we assessed the effects of long term treatment with ω3-PUFAs on NHE-1 in healthy rabbits and in a rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload. To specifically address the effects of a diet rich in ω3-PUFAs from FO on NHE-1 in our study, we chose to use the ω9-MUFAs as a control fatty acids. These fatty are more abundantly present in the human diet and do not alter cardiac electrophysiology (den Ruijter et al., 2008). Therefore, rabbits were fed a diet rich in either ω3-PUFAs from FO or omega-9 monounsaturated fatty acids (ω9-MUFAs) from high-oleic sunflower oil (HOSF) as control.

Materials and Methods

Animals and diet

All experiments were carried out in accordance with guidelines of the local institutional animal care and use committee. In addition, the investigation conforms the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Male New Zealand White rabbits (4 months old) received a diet (150 g/day; Research Diet Services, Wijk bij Duurstede, Netherlands) supplemented with either 1.25% (w/w) FO or 1.25% HOSF as control. Food consumption of every rabbit was measured and average food intake did not differ between FO and HOSF fed animals (data not shown). In the HF model, diet started 1 week before the surgical procedures to induce HF (see below). Lipids from the diet and the left ventricular tissue were extracted with the method of Folch et al. (1957). Table 1 summarizes the fatty acid composition of these diets. In short, the total PUFA content was higher in the ω3-PUFAs diet due to a larger amount of both EPA and DHA.

Table 1.

Fatty acid composition of ω9-MUFA and ω3-PUFA diets.

| ω9-MUFA | ω3-PUFA | |

|---|---|---|

| SATURATED FATTY ACIDS | ||

| Total | 16.2 | 21.8 |

| MONOUNSATURATED FATTY ACIDS | ||

| Total | 44.0 | 17.9 |

| C18:1ω9 (oleic acid) | 42.4 | 12.2 |

| POLYUNSATURATED FATTY ACIDS | ||

| Total | 37.6 | 56.6 |

| C18:2ω6 (LA) | 30.5 | 26.8 |

| C18:3ω3 (ALA) | 6.85 | 7.12 |

| C20:4ω6 (AA) | 0.00 | 0.57 |

| C20:5ω3 (EPA) | 0.1 | 9.2 |

| C22:6ω3 (DHA) | 0.1 | 6.3 |

| Other, unidentified fatty acids | 2.2 | 3.6 |

Fatty acid composition expressed as percentage of total fatty acids. ω9-MUFA, high-oleic sunflower oil; ω3-PUFA, fish oil; LA, linoleic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; AA, arachidonic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid. The sum of listed components is less than the totals indicated here, since not all components were analyzed.

Heart failure was induced by combined volume- and pressure-overload in two sequential surgical procedures as described previously in detail (Vermeulen et al., 1994; Baartscheer et al., 2003a; Verkerk et al., 2007). In short, volume overload was produced by catheter-induced damage to the aortic valve until pulse pressure was increased by about 100%. Three weeks later, pressure-overload was created by abdominal aortic stenosis by ligation of approximately 50%. After 3 weeks for the healthy animals and after 4 months for the HF animals, the rabbits were anesthetized [(ketamine (50 mg i.m.) and xylazine (10 mg i.m.)], heparinized (5000 IU), and killed by intravenous injection of pentobarbital (240 mg).

Cell preparation

Single midmyocardial myocytes were isolated by enzymatic dissociation from the most apical part of the left ventricular free wall as described previously (de Groot et al., 2003). Small aliquots of cell suspension were put in a recording chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope. Myocytes were allowed to adhere for 5 min after which superfusion with Tyrode’s solution was started. Tyrode’s solution (36 ± 0.2°C) contained (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.0, glucose 5.5, HEPES 5.0, pH 7.4 (NaOH). Quiescent rod-shaped cross-striated myocytes with a smooth surface were selected for measurements.

Intracellular pH measurements

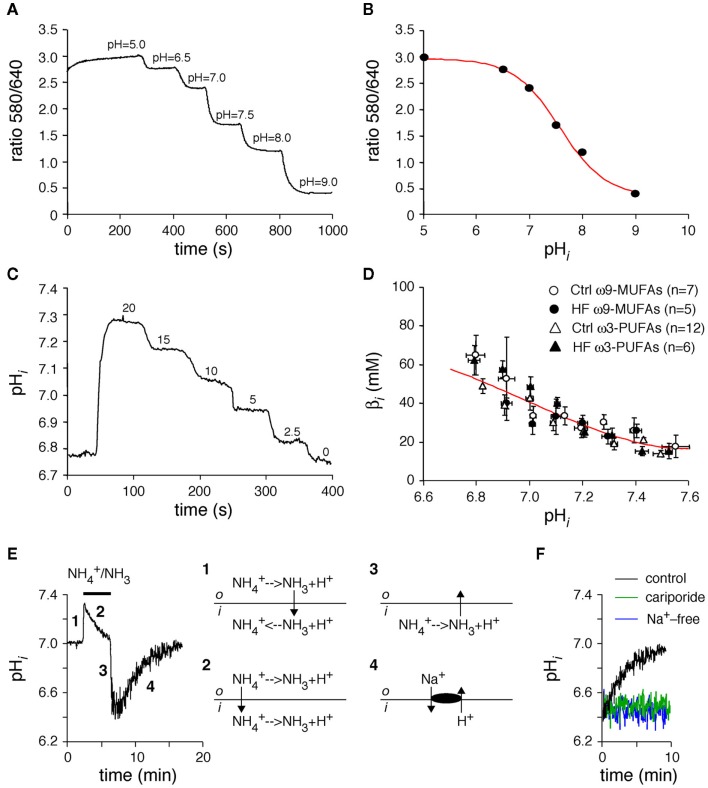

Intracellular pH (pHi) was measured in carboxy-seminaphthorhodafluor-1 (SNARF-AM, Molecular Probes) loaded myocytes as described previously (Baartscheer et al., 2003a; van Borren et al., 2004). In short, myocytes were excited at 515 nm (75 W Xenon arc lamp) and dual wavelength emission of SNARF was recorded at wavelengths of 580 nm (I580) and 640 nm (I640). A rectangular adjustable slit ensured negligible background fluorescence levels. As shown in a typical example in Figure 1A, the I580/I640 ratio was calibrated by a series of precisely set pH solutions that contained 140 mM K+ instead of Na+ and the K+/H+ ionophore nigericin (10 μM; Sigma). Figure 1B shows the resulting calibration curve were the 580/640 ratios were plot against the pHi.

Figure 1.

(A,B) In vivo calibration curve of SNARF-AM. To determine calibration curve myocytes were loaded with SNARF-AM and superfused in presence op nigericin with several high K+ solutions at various pHo values (A). When the external and internal K+ free concentrations are equal, pHi is the same as pHo. The calibration curve (B) was obtained by plotting the ratios (580/640) against the corresponding pHo. The red line represents a Henderson–Hasselbalch fit through these data, which revealed a maximum ratio of 2.97 and a minimum ratio of 0.36 and a pKa of 7.57. (C,D) Determination of the intrinsic sarcoplasmic buffer power (βi). Typical example of the “stepwise reduction in extracellular NH3/NH4+ approach” in a myocyte isolated from a healthy, ω3-PUFA fed animal (C), and pHi–βi relationships of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA myocytes of both healthy rabbits (Ctrl) and the rabbits with heart failure (HF). (E) Typical example and schematic explanation of an ammonium prepulse. (F) Typical examples of effects of Na+-free conditions and cariporide on the acid load recovery in HEPES-buffered conditions.

Intrinsic buffering power

In general, activities of acid loaders or extruders are expressed as the amount of acid or base extruded or loaded per second, the proton flux (JH; Roos and Boron, 1981). Changes in pHi are not linearly related to JH due to the presence of a pHi-dependent intrinsic sarcoplasmic buffer power (βi). βi was determined by the “stepwise reduction in extracellular NH3/NH4+ approach” as described previously (Boyarsky et al., 1988), and shown in the typical example of Figure 1C. With each stepwise decrease in extracellular NH3/NH4+, the amount of protons delivered to the cytoplasm (Δ[acid]i) was considered equal to the resultant change in intracellular NH4+ concentration, which can be calculated from the observed pHi. ΔpHi was taken as the change in pHi produced by the stepwise decrease in extracellular NH3/NH4+. βi was then calculated as −Δ[acid]i/ΔpHi (Roos and Boron, 1981). βi was assigned to the mean of the two pHi values used for its calculation. Figure 1D shows the pHi–βi relationships of myocytes isolated from ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed healthy rabbits and of myocytes of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed rabbits with model of volume- and pressure-overload. The pHi–βi relationships did not differ significantly, indicating that neither the diets nor HF affect the βi.

NHE-1 activity

Na+/H+-exchanger isoform-1 activity was measured in HEPES-buffered conditions as recovery rate from acidosis due to ammonium prepulses as described previously (van Borren et al., 2004). Figure 1E shows a typical example and explanation of the pH changes in response to an ammonium prepulse. In short, 20 mM NH4Cl (NH4+/NH3) was rapidly added to the Tyrode’s solution resulting instantly in alkalinization of myocytes (Figure 1E, phase 1), after which they slowly recovered from alkalization mainly because of NH4+ influx (Figure 1E, phase 2). After withdrawal of NH4+/NH3 from the extracellular solutions all intracellular NH4+ is converted to NH3 which leaves the myocyte and the remaining H+ acidifies the sarcoplasm (Figure 1E, phase 3). Subsequently, in HEPES-buffered solutions, the myocytes slowly recovered from the acid load due to NHE-1 activity (Figure 1E, phase 4). The recovery from acid load is Na+-dependent as well as blocked by cariporide (10 μM; Figure 1F), typical hallmarks of the NHE-1. From the pHi traces we computed the dpHi/dt’s and multiplied these with βi to arrive at JNHE-1.

Cellular electrophysiology

Action potentials (APs) and delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) were recorded with the perforated patch-clamp technique using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Signals were low-pass filtered with a cut-off frequency of 2 kHz and digitized at 3 kHz. Data acquisition and analysis were accomplished using custom software and potentials were corrected for liquid junction potential (Barry and Lynch, 1991). APs were elicited at 3 Hz by 3-ms long, 1.2× threshold current pulses through the patch pipette. We analyzed resting membrane potential (RMP), maximal upstroke velocity (Vmax), AP amplitude (APA), and AP duration at 20, 50, and 90% repolarization (APD20, APD50, and APD90, respectively). Susceptibility to DADs were evoked by a 3-Hz (10-s) rapid pacing episode followed by an 8-s pause (tracing period) in the presence of norepinephrine (100 nM, Centrafarm, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands). A DAD was defined as a temporary, short-lived deviation from (an otherwise stable) RMP of more than 2 mV. Data from five APs and five rapid pacing episode were averaged. Cell membrane capacitance, an electrophysiological measure of cell size, was estimated as we described previously in detail (Verkerk et al., 2004).

Statistics

Data are mean ± SEM. Groups were compared using Two-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA followed by pairwise comparison using the Student–Newman–Keuls test, Fisher’s exact test, or unpaired t-test. P < 0.05 is considered statistical significant.

Results

ω3-PUFA rich diet results in ω3-PUFAs incorporated in the cell membrane

The diet rich in ω3-PUFAs from FO resulted in a significant increase of ω3-PUFAs EPA and DHA of the total amount of fatty acids extracted from the heart of both healthy and HF rabbits (Table 2). The total amount of monounsaturated fatty acids, however, was significantly lower in the ω3-PUFAs fed rabbit hearts compared to the ω9-MUFAs fed rabbit hearts. Thus, ω3-PUFAs from the diet were incorporated in the cell membrane at the expense of monounsaturated fatty acids.

Table 2.

Phospholipid composition of the heart (% of total fat extracted).

| Healthy rabbits |

HF rabbits |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ω9-MUFA (n = 3) | ω3-PUFA (n = 5) | ω9-MUFA (n = 10) | ω3-PUFA (n = 8) | |

| SATURATED FATTY ACIDS | ||||

| Total | 29 ± 3 | 29 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 |

| MONOUNSATURATED FATTY ACIDS | ||||

| Total | 31 ± 4 | 22 ± 2* | 23 ± 2 | 17 ± 1* |

| C18:1ω9 (oleic acid) | 26 ± 4 | 17 ± 2* | 19 ± 2 | 13 ± 1* |

| POLYUNSATURATED FATTY ACIDS | ||||

| Total | 38 ± 6 | 47 ± 3 | 47 ± 1 | 51 ± 1* |

| C18:2ω6 (LA) | 28 ± 3 | 28 ± 1 | 32 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 |

| C18:3ω3 (ALA) | 3.8 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| C20:4ω6 (AA) | 4.7 ± 3.2 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 5.7 ± 0.6 |

| C20:5ω3 (EPA) | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 1* | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.3* |

| C22:6ω3 (DHA) | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 1.4* | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.5* |

| Unidentified fatty acids | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 7.2 ± 0.9 |

Fatty acid composition expressed as percentage of total fatty acids. ω9-MUFA, high-oleic sunflower oil; ω3-PUFA, fish oil; LA, linoleic acid; ALA, α-linolenic acid; AA, arachidonic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid. The sum of listed components is less than the totals indicated here, since not all components were analyzed. *P < 0.05 ω9-MUFA vs. 3-PUFA diet.

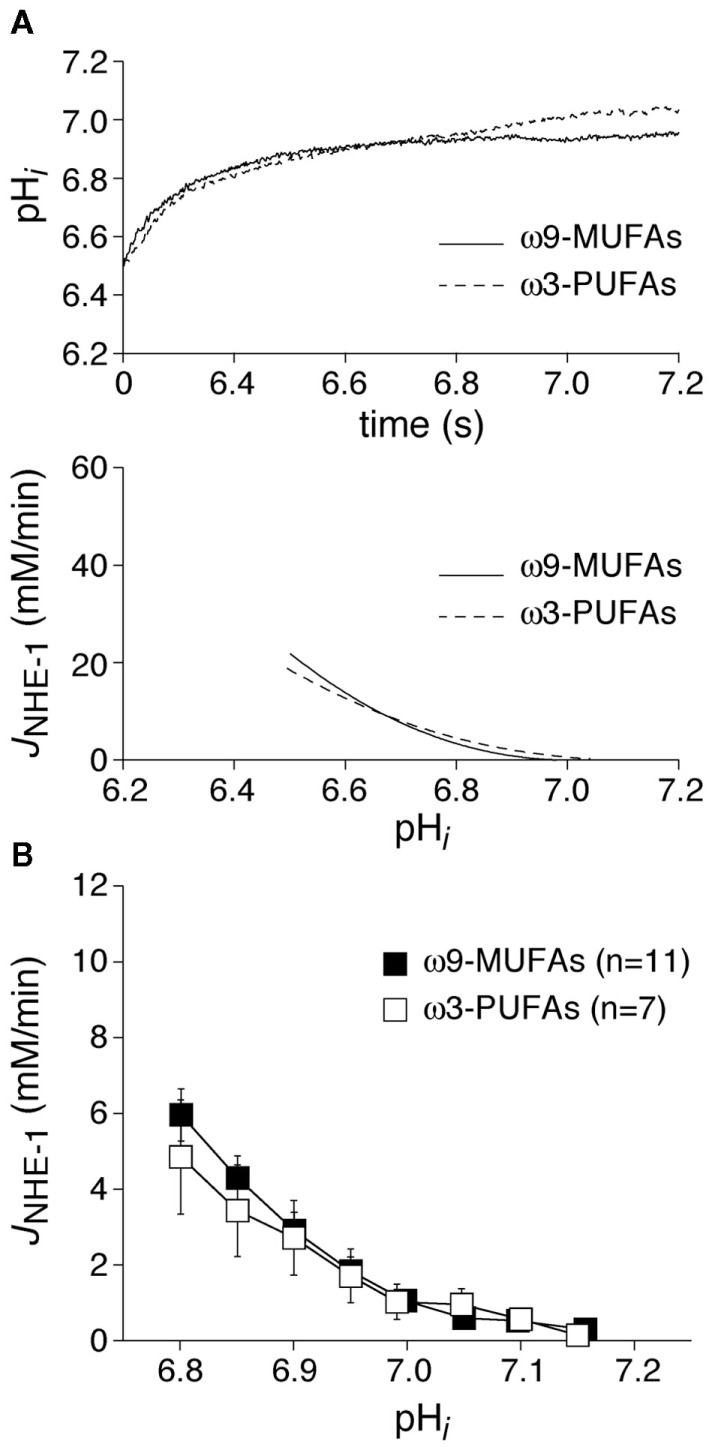

Dietary ω3-PUFAs do not affect NHE-1 activity in healthy rabbits

In a first series of experiments, we measured the NHE-1 in myocytes isolated from healthy rabbits. Body weight after 3 weeks of diet was similar in ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed animals (3.1 ± 0.2, n = 9) vs. 2.9 ± 0.2 kg (n = 7), P > 0.05). Figure 2A, top panel, shows representative recordings of the pHi recovery after an ammonium prepulse (see Materials and Methods) in a myocyte isolated from an ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed rabbit. The pHi recovery, and consequently the calculated JNHE-1 (Figure 2A, bottom panel), was virtually overlapping in the myocytes of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed animals. Figure 2B shows the average JNHE-1 in the myocytes of ω3-PUFA ω9-MUFA fed animals. The average JNHE-1 was not significantly different in the myocytes of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed animals at any of the pHi’s.

Figure 2.

(A) Typical examples of pHi recovery after an ammonium prepulse (top) and the calculated JNHE-1 (bottom) in an ω9-MUFA and ω3-PUFA myocyte isolated from healthy animals. (B) Average JNHE-1 in myocytes of ω9-MUFA and ω3-PUFA fed healthy animals.

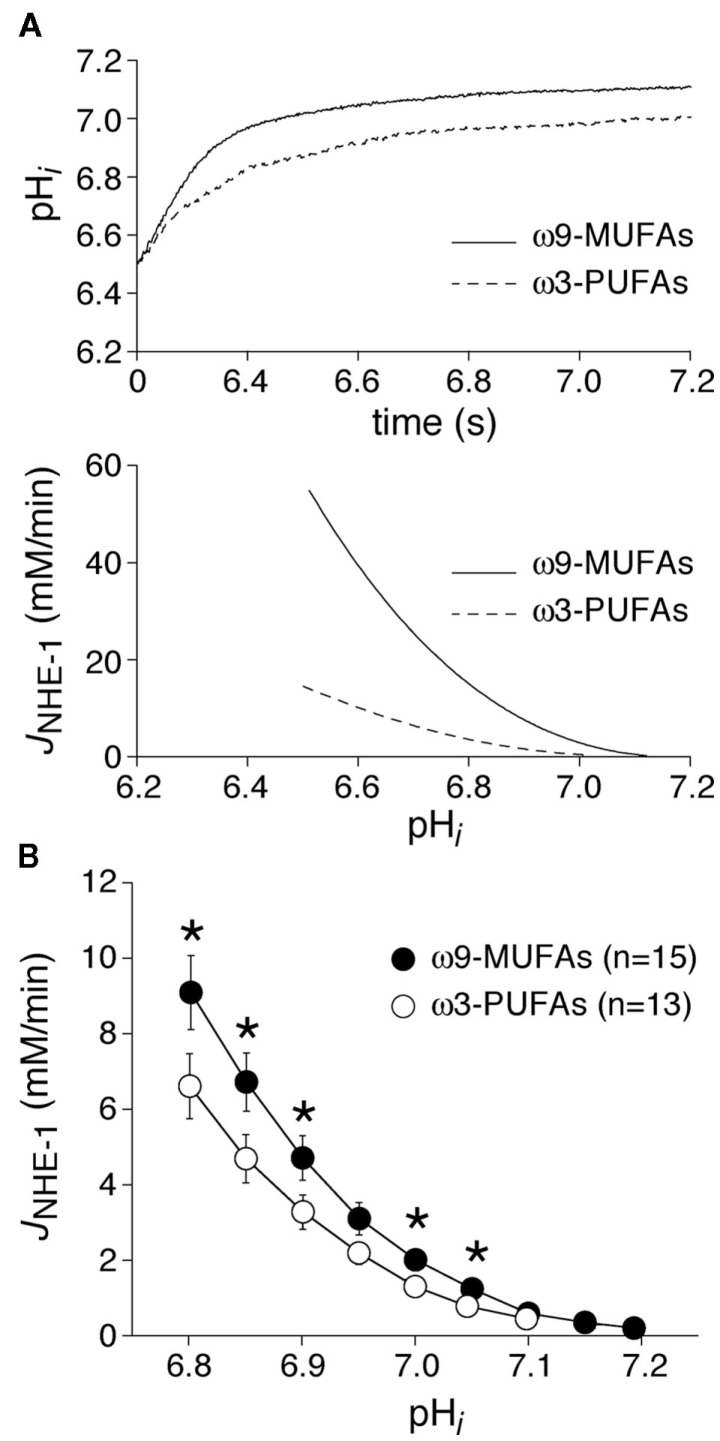

Dietary ω3-PUFAs reduces the NHE-1 activity in a rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload

In a second series of experiments, we studied the NHE-1 activity in myocytes isolated from rabbits that underwent model of volume- and pressure-overload for 4 months. Figure 3A, top panel, shows representative of the pHi recovery after an ammonium prepulse in a myocyte of an ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed animal. In the HF rabbits, pHi recovery after an ammonium prepulse was slower in the myocyte of the ω3-PUFA animal compared to that in the myocyte of the ω9-MUFA fed animal. Consequently, the calculated JNHE-1 was lower in the myocyte of the ω3-PUFA rabbit (Figure 3A, bottom panel). Figure 3B shows the average JNHE-1 in myocytes of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed HF animals. The average JNHE-1 was significantly lower in myocytes of ω3-PUFA animals at pH values lower than 7.1 (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

(A) Typical examples of pHi recovery after an ammonium prepulse (top) and the calculated JNHE-1 (bottom) in an ω9-MUFA and ω3-PUFA myocyte isolated from rabbit which underwent volume- and pressure-overload. (B) Average JNHE-1 in myocytes isolated from ω9-MUFA and ω3-PUFA fed rabbits with volume- and pressure-overload. *P < 0.05.

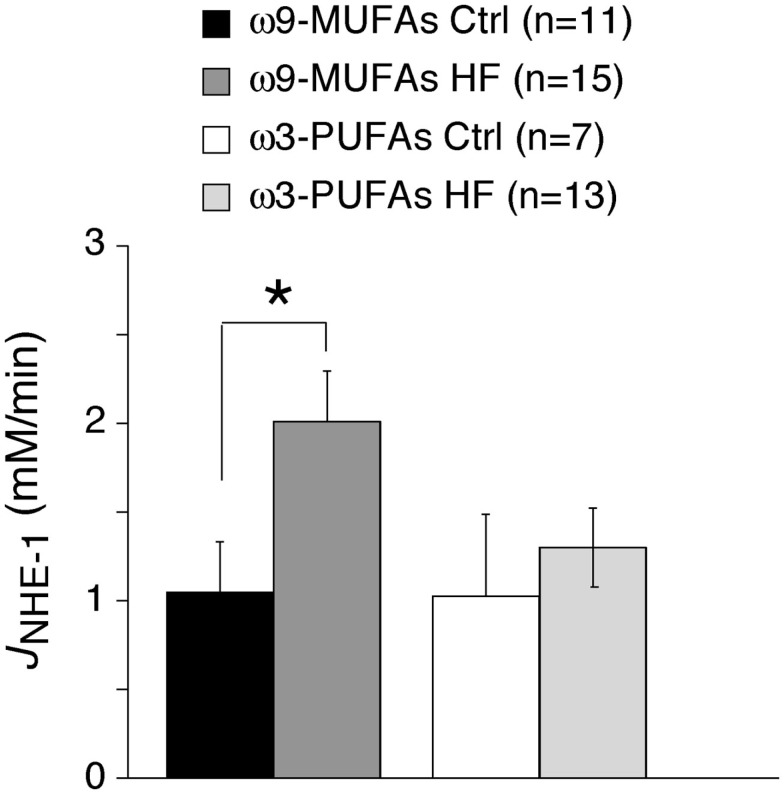

Dietary ω3-PUFAs oppose the increase in NHE-1 activity induced by heart failure

In HF animals, but not in healthy animals, NHE-1 activity in ω3-PUFAs myocytes was significantly lower than in ω9-MUFAs myocytes (Figures 2B and 3B). Previous studies demonstrate that the NHE-1 activity is significantly increased in animal and patients with HF (Baartscheer et al., 2003a; Chahine et al., 2005; van Borren et al., 2006). This suggests that dietary ω3-PUFAs suppress the increase in NHE-1 activity in our rabbit HF model. Figure 4 shows the averages JNHE-1 at pH 7.0 of myocytes of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed healthy and HF animals. HF significantly increased the JNHE-1 in myocytes of ω9-MUFA fed animals (P < 0.05), but not in myocytes of ω3-PUFA fed animals. Thus, a diet rich in ω3-PUFAs suppresses the increase in NHE-1 activity associated with HF.

Figure 4.

Average JNHE-1 at pH = 7.0 of healthy (Ctrl) and HF rabbits fed ω9-MUFA and ω3-PUFA rich diets. Note that JNHE-1 is increased in the HF model in ω9-MUFA fed animals, while it was not changed in ω3-PUFA animals. *P < 0.05.

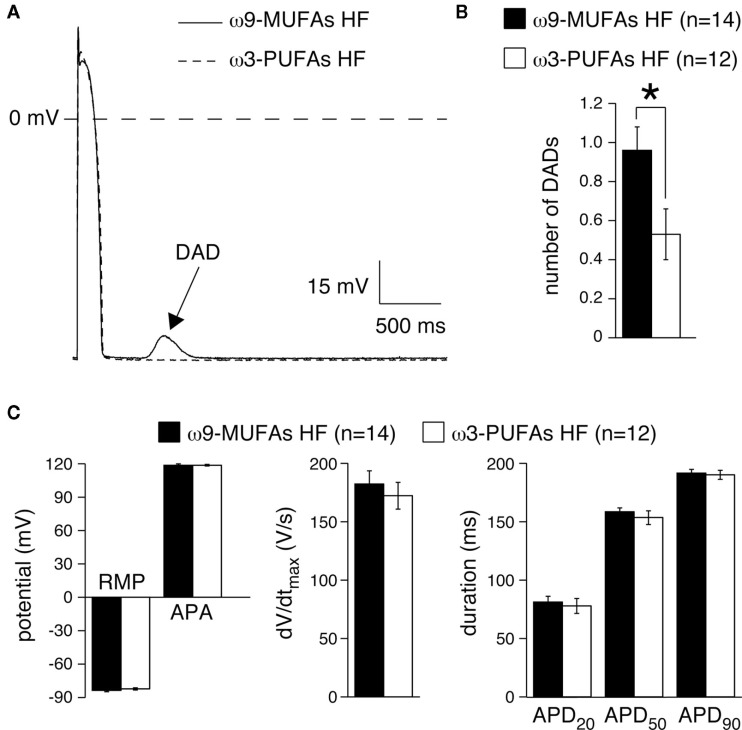

Dietary ω3-PUFAs reduces the incidence of DADs in a rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload

Volume- and pressure-overload in rabbit increased the NHE-1 activity resulting in elevated [Na+]i and secondarily to increased [Ca2+]i (Baartscheer et al., 2003a). The altered Ca2+ handling in HF is associated with spontaneous Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR; Baartscheer et al., 2003b), which activate the transient inward current, Iti, resulting in DADs (Verkerk et al., 2000a). ω3-PUFAs, and not ω9-MUFA, suppress the increase in NHE-1 activity in our rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload. Thus, we hypothesized that the incidence of DADs is lower in myocytes of ω3-PUFAs fed HF rabbits compared to those of ω9-MUFA fed HF rabbits. Next, we tested the susceptibility to induced DADs in HF myocytes by rapid pacing in the presence of 100 nM noradrenalin.

Figure 5A shows typical examples of APs and DAD of myocytes isolated from an ω3-PUFA and an ω9-MUFA fed HF animal. In the myocyte of the ω9-MUFA fed HF rabbit, but not in the myocyte of the ω3-PUFA fed HF rabbit, a DAD (arrow) was present. The amount of myocytes with more than one DAD was significantly lower (P < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test) in ω3-PUFA fed HF rabbits compared to those of ω9-MUFA fed HF animal (Table 3). In addition, the number of DADs was significantly lower in the myocytes of ω3-PUFA fed HF rabbits (Figure 5B). Figure 5C summarizes the average AP characteristics at 3 Hz of myocytes isolated from ω3-PUFA and an ω9-MUFA fed HF animal in the presence of 100 nM noradrenaline. In presences of 100 nM noradrenaline, no AP differences were observed between myocytes of ω3-PUFA and an ω9-MUFA fed HF animal.

Figure 5.

(A) Typical examples of action potentials (AP) and delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs, arrow). (B) Average number of DADs, (C) Average AP characteristics. RMP, resting membrane potential; APA, AP amplitude; dV/dtmax, maximal AP upstroke velocity; APD20, APD50, and, APD90, AP duration at 20, 50, and 90% repolarization, respectively, *P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Susceptibility to induce delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs).

| Fewer than 1 DAD | 1 or more DAD | |

|---|---|---|

| ω9-MUFA | 2 | 12 |

| ω3-PUFA | 7 | 5 |

Number of myocytes. Values indicate the number of myocytes having <1 or ≥1 DAD (average of five tracings). The susceptibility to induce DADs is significantly lower in ω3-PUFA compared to ω9-MUFA myocytes (P < 0.05, Fisher’s exact test).

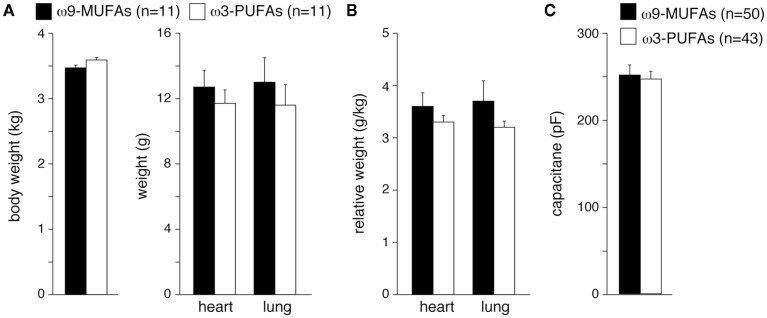

Hypertrophy is similar in ω3-PUFAs and ω9-MUFAs fed rabbits

Various studies demonstrate that ω3-PUFAs suppress development of hypertrophy and HF (Takahashi et al., 2005; Duda et al., 2007; Ramadeen et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011). Because cardiac hypertrophy leads to a decrease of the surface to volume ratio of myocytes, an increased number of NHE-1 proteins are required to maintain a normal “cytoplasmic” NHE-1 mediated acid load recovery. The maintained cytoplasmic NHE-1 activity observed in cardiomyocytes from ω3-PUFAs treated HF rabbits (Figure 4) may thus be explained also by a lower degree of hypertrophy. Therefore, we finally analyzed important parameters for hypertrophy and HF in ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed rabbits, which underwent volume- and pressure-overload. Body, lung, and heart weight were similar in ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA rabbits (Figure 6A). Consequently, relative lung weight and relative heart weight, an index of cardiac hypertrophy, were not significantly different (Figure 6B). While previously we observed relative heart weights of 2.2–2.5 in non-failing rabbits with a standard chow diet (Baartscheer et al., 2003a,b, 2005, 2008; de Groot et al., 2003; van Borren et al., 2006), the relative heart weights in the present study of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed rabbits were 3.6 ± 0.26 and 3.3 ± 1.13, respectively. Thus, despite the absence of differences in degree of hypertrophy, both ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed HF rabbit hearts are equally hypertrophied. Moreover, cell capacitance, an electrophysiological measure of cell size, was not significantly different between myocytes of ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA rabbits (Figure 6C). Furthermore, the presence of ascites assessed at autopsy was the same in ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA rabbits. These data indicate that the degree of hypertrophy and HF are similar in ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed rabbits.

Figure 6.

(A) Average body, lung, and heart weight in ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA fed rabbits which underwent volume- and pressure-overload. n, Number of rabbits (B), Relative lung weight and relative heart weight, an index of cardiac hypertrophy, in ω3-PUFA, and ω9-MUFA fed rabbits which underwent volume- and pressure-overload. (C) Average cell membrane capacitance of myocytes isolated from ω3-PUFA and ω9-MUFA rabbits. n, Number of myocytes. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Overview

In this study we examined the effects of dietary ω3-PUFAs on NHE-1 of myocytes from healthy and failing hearts. In general, NHE-1 inhibition is thought to be a pharmacological tool for the treatment of various detrimental cardiac conditions such as ischemia/reperfusion injury, arrhythmias, hypertrophy, and HF. In many pre-clinical studies, NHE-1 inhibition has been shown to reduce ischemia/reperfusion injury (Lee et al., 2005; Ayoub et al., 2010). In clinical trials, however, the cardioprotective effects of NHE-1 inhibition were less clear and the treatment with the NHE-1 inhibitor cariporide was associated with significantly greater incidence of stroke (Fliegel and Karmazyn, 2004). These adverse effects halted the further use of cariporide as cardioprotective agent.

Cardiac NHE-1 activity is also significantly increased in animal and patients with HF (Baartscheer et al., 2003a; Chahine et al., 2005). Pre-clinical studies demonstrated that chronic inhibition of NHE-1 leads to reversal of cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy and HF, and improved contractility in HF models in mice (Engelhardt et al., 2002), rats (Camillión de Hurtado et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2004), and rabbit (Baartscheer et al., 2005, 2008). In rabbit studies, a diet containing the NHE-1 inhibitor cariporide not only reversed hypertrophy and reduced signs of HF, but also reversed cardiac ionic and electrical remodeling and prevented changes in myocyte dimensions, AP duration, and NHE-1 fluxes (Baartscheer et al., 2005, 2008). In addition, Ca2+ homeostasis remained undisturbed, and no increase of the incidence of Ca2+ after transient dependent DADs occurred (Baartscheer et al., 2005). From the prevention of excessive fibrosis, prolongation of AP duration, and DADs (Nuss et al., 1999; Marx et al., 2000; Sipido et al., 2000; Janse, 2004; Pogwizd and Bers, 2004), one may infer that NHE-1 inhibition is also anti-arrhythmic. Thus, at least part of the beneficial effects of ω3-PUFAs may be attributed to NHE-1 inhibition during HF.

Dietary ω3-PUFAs do not suppress the NHE-1 in myocytes of healthy animals

In myocytes isolated from healthy animals, we found that ω3-PUFAs do not affect the NHE-1 activity as compared to ω9-MUFAs (Figure 2). Our results contrast with a study by Goel et al. (2002) that showed that ω3-PUFAs reduced the NHE-1 activity. This discrepancy is likely due to study design. We studied dietary ω3-PUFAs intake that causes ω3-PUFA incorporation into cardiac cell membranes (Owen et al., 2004), whereas Goel et al. (2002) studied direct application of ω3-PUFAs on cardiac myocytes. Acutely applied ω3-PUFAs and incorporated ω3-PUFAs have different effects on cardiac electrophysiology (den Ruijter et al., 2007, 2010; Verkerk et al., 2009), and our study suggests that it also has a different effect on pHi. Dietary ω3-PUFAs intake does not affect the resting pHi in healthy animals (present study), while acute administration resulted in acidosis (Aires et al., 2003), which could well explain the lower apparent NHE-1 activity observed by Goel et al. Other explanations may be the differences in species (pig vs. rabbit) and the technique used to measure NHE-1 activity (radioactive Na+ uptake in cell suspensions vs. single cell fluorescence).

Dietary ω3-PUFAs suppress NHE-1 upregulation in a rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload

In our rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload, we found that the NHE-1 activity in ω3-PUFAs myocytes was significantly lower than in ω9-MUFAs myocytes (Figure 3). The mechanisms for the lower NHE-1 activity are unknown. One may speculate that ω3-PUFAs affect membrane fluidity (Jahangiri et al., 2000), resulting in a decrease of NHE-1 activity (Bookstein et al., 1997). This membrane fluidity theory is frequently used to explain the effects of ω3-PUFAs on membrane channels, however, but the lack of significant effects of ω3-PUFAs on NHE-1 in healthy animals is not in line of this hypothesis.

A second hypothesis is that ω3-PUFAs attenuate cardiac hypertrophy (Takahashi et al., 2005; Duda et al., 2007; Ramadeen et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011), resulting in a decrease of NHE-1 activity (Baartscheer et al., 2005). In the present study, however, the relative heart weight and cell capacitance, both indices of cardiac hypertrophy, did not differ between ω3-PUFAs and ω9-MUFAs fed rabbits or their myocytes, respectively (Figure 6). This excludes differences in hypertrophy as a likely mechanism. The unaltered degree of hypertrophy is in contrast with observations in mice with transverse aortic constriction (Chen et al., 2011) and juvenile visceral steatosis (Takahashi et al., 2005), rats with abdominal aortic banding (Duda et al., 2007), and rapid-paced dogs (Ramadeen et al., 2010) where dietary supplementation of ω3-PUFAs attenuated cardiac hypertrophy. This discrepancy may be explained by differences in HF model, species, ω3-PUFAs concentration, but also to the control diets used. In our study, the control (ω9-MUFAs) diet was supplemented with HOSF, while in the other studies the control diet was standard chow or supplemented with corn oil. The importance of a proper control diet is supported by the finding that the relative heart weight of ω9-MUFAs fed HF rabbits was ≈3.6 (Figure 6), while in the same rabbit HF model with a standard chow diet we previously measured relative heart weights of 4.4–6.0 in our laboratory (Baartscheer et al., 2003a,b, 2005, 2008; de Groot et al., 2003; van Borren et al., 2006; den Ruijter et al., 2008). This suggests that both ω3-PUFAs and ω9-MUFAs diets reduce the degree of hypertrophy. Further studies are required to address this.

A third hypothesis is that dietary ω3-PUFAs affect cell signaling and enzymes important for NHE-1 activity. The NHE is not only activated by pHi but also by a number of other stimuli. NHE-1 activity is accelerated in response of endothelin, angiotensin II, and G protein and second messenger stimulation of PKC (diacylglycerol) and PKA (forskolin, β1-adrenoreceptor agonists; Kandasamy et al., 1995; Karmazyn et al., 2001; Díaz et al., 2010). Also, mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase-dependent pathways result in the phosphorylation of the NHE (Sartori et al., 1999). ω3-PUFAs affect several of these NHE-1 stimuli. They reduce diacylglycerol and PKC, activate the parasympathetic nervous system, and reduce angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) activity (Mohan and Das, 2001; Seung-Kim et al., 2001; Takahashi et al., 2005), although the latter is not a consistent finding (Ogawa et al., 2009). An intriguing question is why the NHE-1 activity in myocytes of ω3-PUFA fed animals is lower than in myocytes of ω9-MUFA fed animals in our model of volume- and pressure-overload, while it is not different in healthy rabbits. This suggests that the NHE-1 reduction is due to changes in cell signaling pathways active during HF (Onohara et al., 2006; Niizeki et al., 2008). One can speculate that the lower NHE-1 activity also reduces the degree of hypertrophy and HF, but this was not observed in the present study, suggesting that NHE-1 is more sensitive for ω3-PUFAs modulation of cellular signaling pathways than hypertrophy and HF. Alternatively, the time required for hypertrophy and HF attenuation might be longer than that for NHE-1 reduction. The decreased NHE-1 activity may also be the result of a decreased expression of NHE-1.

Dietary ω3-PUFAs suppress DADs

In our HF model of volume-and pressure-overload, we observed that the susceptibility for DAD development was significantly lower in myocytes of ω3-PUFAs fed rabbits compared to those of ω9-MUFAs fed rabbits (Table 3; Figure 6B). DADs occur in [Ca2+]i overload condition (Verkerk et al., 2000a, and primary references cited therein). Thus, our results indicate that myocytes of ω3-PUFAs fed failing rabbits are less sensitive for [Ca2+]i overload development than those of ω 9-MUFAs fed failing rabbits. According to the importance of the NHE-1 for [Ca2+]i (Baartscheer et al., 2003a), it is tempting to speculate that this is due to the lower NHE-1 activity in myocytes of ω3-PUFAs fed HF rabbits. Previously we observed multiple changes in ionic currents due to dietary and acute ω3-PUFAs resulting in AP shortening (Verkerk et al., 2006) and reduced susceptibility of early afterdepolarizations and DADs development (den Ruijter et al., 2006, 2008; Berecki et al., 2007).

Dietary ω3-PUFAs caused an increase of IK1 resulting in a more stable RMP (Verkerk et al., 2006). The latter will result in smaller DAD amplitudes. In addition, dietary ω3-PUFAs decreased INCX (Verkerk et al., 2006), which carries the transient inward current, Iti, responsible for DADs (Verkerk et al., 2000a, and primary references cited therein). Decreased INCX may therefore also result in DADs of smaller amplitude. However, while both changes may reduce the DAD amplitude, they will not reduce the propensity to spontaneous Ca2+ release of the SR and thus DADs. Previously, we observed AP shortening due to dietary ω3-PUFAs (Verkerk et al., 2006). AP shortening leads to an increased diastolic interval, favoring removal of excess Ca2+ from the cytosol. This will reduce [Ca2+]i overload conditions and DAD occurrence (Verkerk et al., 2000b, and primary refs. cited therein). However, in presence of 100 nM noradrenaline, AP duration did not differed significantly between myocytes of ω3-PUFAs and ω9-MUFAs fed HF rabbits (Figure 5C). Thus, in the present study the role of AP duration in susceptibility of DADs is limited, although this cannot be entirely excluded in the absence of data on intracellular calcium and sodium activity.

Conclusion

Dietary ω3-PUFAs from FO suppress upregulation of the NHE-1 activity in a rabbit model of volume- and pressure-overload. The degree of hypertrophy and HF is similar in myocytes of ω3-PUFAs and ω9-MUFAs fed HF rabbits, but the lower NHE-1 activity in myocytes of ω3-PUFAs fed HF rabbits suggests that dietary ω3-PUFAs administration during the development of HF may be anti-arrhythmic via reduction of ischemia/reperfusion injury and Ca2+-modulated arrhythmias.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charly Belterman, Cees Schumacher, and Berend de Jonge for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Netherlands Heart Foundation (2003B079 and 2007B019).

References

- Aires V., Hichami A., Moutairou K., Khan N. A. (2003). Docosahexaenoic acid and other fatty acids induce a decrease in pHi in Jurkat T-cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140, 1217–1226 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub I. M., Kolarova J., Gazmuri R. J. (2010). Cariporide given during resuscitation promotes return of electrically stable and mechanically competent cardiac activity. Resuscitation 81, 106–110 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.09.430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub I. M., Kolarova J., Yi Z., Trevedi A., Deshmukh H., Lubell D. L., Franz M. R., Maldonado F. A., Gazmuri R. J. (2003). Sodium-hydrogen exchange inhibition during ventricular fibrillation: beneficial effects on ischemic contracture, action potential duration, reperfusion arrhythmias, myocardial function, and resuscitability. Circulation 107, 1804–1809 10.1161/01.CIR.0000058704.45646.0D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baartscheer A., Hardziyenka M., Schumacher C. A., Belterman C. N. W., van Borren M. M. G. J., Verkerk A. O., Coronel R., Fiolet J. W. T. (2008). Chronic inhibition of the Na+/H+- exchanger causes regression of hypertrophy, heart failure, and ionic and electrophysiological remodelling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154, 1266–1275 10.1038/bjp.2008.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baartscheer A., Schumacher C. A., van Borren M. M. G. J., Belterman C. N. W., Coronel R., Fiolet J. W. T. (2003a). Increased Na+/H+-exchange activity is the cause of increased [Na+]i and underlies disturbed calcium handling in the rabbit pressure and volume overload heart failure model. Cardiovasc. Res. 57, 1015–1024 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00809-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baartscheer A., Schumacher C. A., Belterman C. N. W., Coronel R., Fiolet J. W. T. (2003b). SR calcium handling and calcium after-transients in a rabbit model of heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 58, 99–108 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00854-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baartscheer A., Schumacher C. A., van Borren M. M. G. J., Belterman C. N. W., Coronel R., Opthof T., Fiolet J. W. T. (2005). Chronic inhibition of Na+/H+-exchanger attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and prevents cellular remodeling in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 65, 83–92 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baartscheer A., van Borren M. M. G. J. (2008). Sodium ion transporters as new therapeutic targets in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 6, 229–236 10.2174/187152508785909546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak M. I., Ingwall J. S. (2003). Contribution of Na+/H+ exchange to Na+ overload in the ischemic hypertrophied hyperthyroid rat heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 57, 1004–1014 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00793-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry P. H., Lynch J. W. (1991). Liquid junction potentials and small cell effects in patch clamp analysis. J. Membr. Biol. 121, 101–107 10.1007/BF01870526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berecki G., den Ruijter H. M., Verkerk A. O., Schumacher C. A., Baartscheer A., Bakker D., Boukens B. J., van Ginneken A. C. G., Fiolet J. W. T., Opthof T., Coronel R. (2007). Dietary fish oil diet reduces the incidence of triggered arrhythmias in pig ventricular myocytes. Heart Rhythm 4, 1452–1460 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein C., Musch M. W., Dudeja P. K., McSwine R. L., Xie Y., Brasitus T. A., Rao M. C., Chang E. B. (1997). Inverse relationship between membrane lipid fluidity and activity of Na+/H+ exchangers, NHE1 and NHE3, in transfected fibroblasts. J. Membr. Biol. 160, 183–192 10.1007/s002329900307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyarsky G., Ganz M. B., Sterzel R. B., Boron W. F. (1988). pH regulation in single glomerular mesangial cells. I. Acid extrusion in absence and presence of HCO3-. Am. J. Physiol. 255, C844–C856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr M. L., Gilbert J. F., Holliday R. M., Elwood P. C., Fehily A. M., Rogers S., Sweetnam P. M., Deadman N. M. (1989). Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART). Lancet 334, 757–761 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90828-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camillión de Hurtado M. C., Portiansky E. L., Pérez N. G., Rebolledo O. R., Cingolani H. E. (2002). Regression of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in SHR following chronic inhibition of the Na+/H+ exchanger. Cardiovasc. Res. 53, 862–868 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00544-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahine M., Bkaily G., Nader M., Al-Khoury J., Jacques D., Beier N., Scholz W. (2005). NHE-1-dependent intracellular sodium overload in hypertrophic hereditary cardiomyopathy: prevention by NHE-1 inhibitor. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 38, 571–582 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Shearer G. C., Chen Q., Healy C. L., Beyer A. J., Nareddy V. B., Gerdes A. M., Harris W. S., O’Connell T. D., Wang D. (2011). Omega-3 fatty acids prevent pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis through activation of cyclic GMP/protein kinase G signaling in cardiac fibroblasts. Circulation 123, 584–593 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chen C. X., Can X. T., Beier N., Scolz W., Karmazyn M. (2004). Inhibition and reversal of myocardial infarction-induced hypertrophy and heart failure by NHE-1 inhibition. Am. J. Physiol. 286, H381–H387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani H. E., Ennis I. L. (2007). Sodium-hydrogen exchanger, cardiac overload, and myocardial hypertrophy. Circulation 115, 1090–1100 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.626929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot J. R., Schumacher C. A., Verkerk A. O., Baartscheer A., Fiolet J. W. T., Coronel R. (2003). Intrinsic heterogeneity in repolarization is increased in isolated failing rabbit cardiomyocytes during simulated ischemia. Cardiovasc. Res. 59, 705–714 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00460-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Ruijter H. M., Berecki G., Opthof T., Verkerk A. O., Zock P. L., Coronel R. (2007). Pro- and antiarrhythmic properties of a diet rich in fish oil. Cardiovasc. Res. 73, 316–325 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Ruijter H. M., Berecki G., Verkerk A. O., Bakker D., Baartscheer A., Schumacher C. A., Belterman C. N. W., de Jonge N., Fiolet J. W. T., Brouwer I. A., Coronel R. (2008). Acute administration of fish oil inhibits triggered activity in isolated myocytes from rabbits and patients with heart failure. Circulation 117, 536–544 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.733329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Ruijter H. M., Verkerk A. O., Berecki G., Bakker D., van Ginneken A. C. G., Coronel R. (2006). Dietary fish oil reduces the occurrence of early afterdepolarizations in pig ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 41, 914–917 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Ruijter H. M., Verkerk A. O., Coronel R. (2010). Incorporated fish oil fatty acids prevent action potential shortening induced by circulating fish oil fatty acids. Front. Physiol. 1:149. 10.3389/fphys.2010.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz R. G., Nolly M. B., Massarutti C., Casarini M. J., Garciarena C. D., Ennis I. L., Cingolani H. E., Pérez N. G. (2010). Phosphodiesterase 5A inhibition decreases NHE-1 activity without altering steady state pHi: role of phosphatases. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 26, 531–540 10.1159/000322321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda M. K., O’Shea K. M., Lei B., Barrows B. R., Azimzadeh A. M., McElfresh T. E., Hoit B. D., Kop W. J., Stanley W. C. (2007). Dietary supplementation with ω3-PUFA increases adiponectin and attenuates ventricular remodeling and dysfunction with pressure overload. Cardiovasc. Res. 76, 303–310 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt S., Hein L., Keller U., Klämbt K., Lohse M. J. (2002). Inhibition of Na+-H+ exchange prevents hypertrophy, fibrosis, and heart failure in β1-adrenergic receptor transgenic mice. Circ. Res. 90, 814–819 10.1161/01.RES.0000014966.97486.C0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegel L. (2009). Regulation of the Na+/H+ exchanger in the healthy and diseased myocardium. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 1, 55–68 10.1517/14728220802600707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegel L., Karmazyn M. (2004). The cardiac Na-H exchanger: a key downstream mediator for the cellular hypertrophic effects of paracrine, autocrine and hormonal factors. Biochem. Cell Biol. 82, 626–635 10.1139/o04-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Lees M., Stanley G. H. S. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators (1999). Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Lancet 354, 447–455 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07072-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel D. P., Maddaford T. G., Pierce G. N. (2002). Effects of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on cardiac sarcolemmal Na+/H+ exchange. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283, H1688–H1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahangiri A., Leifert W. R., Patten G. S., McMurchie E. J. (2000). Termination of asynchronous contractile activity in rat atrial myocytes by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 206, 33–41 10.1023/A:1007025007403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse M. J. (2004). Electrophysiological changes in heart failure and their relationship to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 61, 208–217 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy R. A., Yu F. H., Harris R., Boucher A., Hanrahan J. W., Orlowski J. (1995). Plasma membrane Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms (NHE-1, -2, and -3) are differentially responsive to second messenger agonists of the protein kinase A and C pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29209–29216 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmazyn M., Sostaric J. V., Gan X. T. (2001). The myocardial of Na+/H+ exchanger: a potential therapeutic target for the prevention of myocardial ischaemic and reperfusion injury and attenuation of postinfarction heart failure. Drugs 61, 375–389 10.2165/00003495-200161030-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris-Etherton P. M., Harris H. S., Appel L. J. (2002). Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 106, 2747–2757 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038493.65177.94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. H., Yi K. Y., Lee S., Lee S., Yoo S. E. (2005). Effects of KR-32570, a new sodium hydrogen exchanger inhibitor, on myocardial infarction and arrhythmias induced by ischemia and reperfusion. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 523, 101–108 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan E. B., Wolk A., Mittleman M. A. (2009). Fish consumption, marine omega-3 fatty acids, and incidence of heart failure: a population-based prospective study of middle-aged and elderly men. Eur. Heart J. 30, 1495–1500 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B., Albert C., Anderson M. E., Giles W. R., Van Wagoner D. R., Balk E., Billman G. E., Chung M., Lands W., Leaf A., McAnulty J., Martens J. R., Costello R. B., Lathrop D. A. (2007). Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiac arrhythmias: prior studies and recommendations for future research: a report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office Of Dietary Supplements Omega-3 Fatty Acids and their Role in Cardiac Arrhythmogenesis Workshop. Circulation 116, e320–e335 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx S. O., Reiken S., Hisamatsu Y., Jayaraman T., Burkhoff D., Rosemblit N., Marks A. R. (2000). PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell 101, 365–376 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80847-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan I. K., Das U. N. (2001). Effect of L-arginine-nitric oxide system on the metabolism of essential fatty acids in chemical induced diabetes mellitus in experimental animals by polyunsaturated fatty acids. Nutrition 17, 126–151 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00468-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D., Bryson C. L., Lemaitre R. N., Burke G. L., Siscovick D. S. (2005). Fish intake and risk of incident heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 2015–2021 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T. Y., Iwata Y., Arai Y., Komamura K., Wakabayashi S. (2008). Activation of Na+/H+ exchanger 1 is sufficient to generate Ca2+ signals that induce cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ. Res. 103, 891–899 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niizeki T., Takeishi Y., Kitahara T., Arimoto T., Ishino M., Bilim O., Suzuki S., Sasaki T., Nakajima O., Walsh R. A., Goto K., Kubota I. (2008). Diacylglycerol kinase-ε restores cardiac dysfunction under chronic pressure overload: a new specific regulator of Gαq signaling cascade. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295, H245–H255 10.1152/ajpheart.00066.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuss H. B., Kääb S., Kass D. A., Tomaselli G. F., Marbán E. (1999). Cellular basis of ventricular arrhythmias and abnormal automaticity in heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. 277, H80–H91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa A., Suzuki Y., Aoyama T., Takeuchi H. (2009). Dietary alpha-linolenic acid inhibits angiotensin-converting enzyme activity and mRNA expression levels in the aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Oleo Sci. 58, 355–360 10.5650/jos.58.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onohara N., Nishida M., Inoue R., Kobayashi H., Sumimoto H., Sato Y., Mori Y., Nagao T., Kurose H. (2006). TRPC3 and TRPC6 are essential for angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J. 25, 5305–5316 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen A. J., Peter-Przyborowska B. A., Hoy A. J., McLennan P. L. (2004). Dietary fish oil dose- and time-response effects on cardiac phospholipid fatty acid composition. Lipids 39, 955–961 10.1007/s11745-004-1317-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd S. M., Bers D. M. (2004). Cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 14, 61–66 10.1016/j.tcm.2003.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadeen A., Laurent G., dos Santos C. C., Hu X., Connelly K. A., Holub B. J., Mangat I., Dorian P. (2010). n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids alter expression of fibrotic and hypertrophic genes in a dog model of atrial cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 7, 520–528 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos A., Boron W. F. (1981). Intracellular pH. Physiol. Rev. 61, 296–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori M., Ceolotto G., Semplicini A. (1999). MAP Kinase and regulation of the sodium-proton exchanger in human red blood cell. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1421, 140–148 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00121-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seung-Kim H. F., Weeber E. J., Sweatt J. D., Stoll A. L., Marangell L. B. (2001). Inhibitory effects of omega-3 fatty acids on protein kinase C activity in vitro. Mol. Psychiatry 6, 246–248 10.1038/sj.mp.4000837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipido K. R., Volders P. G., de Groot S. H., Verdonck F., Van de Werf F., Wellens H. J., Vos M. A. (2000). Enhanced Ca2+ release and Na/Ca exchange activity in hypertrophied canine ventricular myocytes: potential link between contractile adaptation and arrhythmogenesis. Circulation 102, 2137–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Okumura K., Asai T., Hirai T., Murakami H., Murakami R., Numaguchi Y., Matsui H., Ito M., Murohara T. (2005). Dietary fish oil attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy due to systemic carnitine deficiency. Cardiovasc. Res. 68, 213–223 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Borren M. M. G. J., Baartscheer A., Wilders R., Ravesloot J. H. (2004). NHE-1 and NBC during pseudo-ischemia/reperfusion in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 37, 567–577 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Borren M. M. G. J., Zegers J. G., Baartscheer A., Ravesloot J. H. (2006). Contribution of NHE-1 to cell length shortening of normal and failing rabbit cardiac myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 41, 706–715 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan-Jones R. D., Spitzer K. W., Swietach P. (2009). Intracellular pH regulation in heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 46, 318–331 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk A. O., den Ruijter H. M., Bourier J., Boukens B. J., Brouwer I. A., Wilders R., Coronel R. (2009). Dietary fish oil reduces pacemaker current and heart rate in rabbit. Heart Rhythm 6, 1485–1492 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk A. O., Tan H. L., Ravesloot J. H. (2004). Ca2+-activated Cl- current reduces transmural electrical heterogeneity within the rabbit left ventricle. Acta Physiol. Scand. 180, 239–247 10.1111/j.0001-6772.2003.01252.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk A. O., van Ginneken A. C. G., Berecki G., den Ruijter H. M., Schumacher C. A., Veldkamp M. W., Baartscheer A., Casini S., Opthof T., Hovenier R., Fiolet J. W. T., Zock P. L., Coronel R. (2006). Incorporated sarcolemmal fish oil fatty acids shorten pig ventricular action potentials. Cardiovasc. Res. 70, 509–520 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk A. O., van Ginneken A. C. G., van Veen T. A. B., Tan H. L. (2007). Effects of heart failure on brain-type Na+ channels in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Europace 9, 571–577 10.1093/europace/eum121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk A. O., Veldkamp M. W., Bouman L. N., van Ginneken A. C. G. (2000a). Calcium-activated Cl- current contributes to delayed afterdepolarizations in single Purkinje and ventricular myocytes. Circulation 101, 2639–2644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk A. O., Veldkamp M. W., de Jonge N., Wilders R., van Ginneken A. C. G. (2000b). Injury current modulates afterdepolarizations in single human ventricular cells. Cardiovasc. Res. 47, 124–132 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00064-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen J. T., McGuire M. A., Opthof T., Coronel R., de Bakker J. M. T., Klöpping C., Janse M. J. (1994). Triggered activity and automaticity in ventricular trabeculae of failing human and rabbit hearts. Cardiovasc. Res. 28, 1547–1554 10.1093/cvr/28.10.1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi K., Iso H., Date C., Fukui M., Wakai K., Kikuchi S., Inaba Y., Tanabe N., Tamakoshi A. (2008). Fish, ω−3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and mortality from cardiovascular diseases in a nationwide community-based cohort of Japanese men and women: the JACC (Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for evaluation of cancer risk) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52, 988–996 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]