Abstract

Background

The number of pathological gamblers seeking treatment has risen continuously till the present, and the trend shows no sign of reversal. Estimates of the number of pathological gamblers in Germany range from 103 000 to 290 000, corresponding to 0.2% to 0.6% of the population. Pathological gambling often accompanies other mental disturbances. Doctors who learn that their patients suffer from such disturbances should ask targeted questions about gambling behavior to increase the chance that this problem will be detected early on.

Methods

This article is based on an analysis of secondary data obtained from the German Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme and the Federal Statistical Office and on a selective review of the literature on comorbidities and available interventions.

Results

The rate of inpatient treatment for pathological gambling tripled from 2000 to 2010. Most pathological gamblers are men (70%–80%). More than 90% of the patients suffer from more than one mental disturbance; 40% of them carry five different psychiatric diagnoses. Simple screening instruments for pathological gambling are easy to use in routine practice and facilitate the diagnosis.

Conclusion

As with alcoholics, only a small fraction of pathological gamblers receives the appropriate support and treatment. Educational seminars to raise awareness among physicians and targeted measures for early detection might result in more of the affected persons getting suitable help.

In Germany, the number of patients seeking outpatient or inpatient treatment for gambling addition has risen continually during the past decade. Gambling addiction is the vernacular term for the ICD-10 diagnosis “Pathological gambling” (F63.0). The main characteristic is frequent and repeated episodes of gambling, to quote directly, “that dominate the patient’s life to the detriment of social, occupational, material, and family values and commitments” (e1). In analogy to the use of psychotropic substances, gambling is an effective but inadequate strategy used to cope with stressors or stresses (1). Imaging methods have shown that persons with substance related disorders and pathological gamblers resemble each other in the patterns of their neurological amplification mechanisms (2). Many of those affected are given medical treatment for their mental comorbidities, but the pathological gambling is not mentioned. The aim should be to identify as many pathological gamblers as possible in routine clinical practice and to provide early treatment.

After a brief explanation of the legal framework in Germany, this article will set out diagnostic criteria and a brief screening instrument for routine clinical practice. In this context we will show different types and common characteristics of gamblers. We will go on to present secondary data about trends in the prevalence rates of treatment. Subsequently we will introduce commonly encountered comorbidities. We hope that these insights will enable treating physicians to identify the problem early on. Following on from that we will briefly describe the support services that are available to those affected.

Legal framework

In Germany, gambling is prohibited as a demerit good according to sections 284ff of the penal code. In order to enable legal gambling, games that are organized as public events and concessions are exempted and are instead regulated by the state treaty relating to the gambling sector in Germany (e2)—the state treaty on gaming in Germany (GlüStV, Glücksspielstaatsvertrag). A vital objective of the treaty is to protect gamblers (section 1 GlüStV). However, gambling in commercial arcades is currently regulated by trade regulations (GewO, Gewerbeordnung; [e3]) or gambling regulations (SpielVO, Spielverordnung; [e4]). Arcade machines are referred to as “gaming apparatus providing an opportunity for winnings” (section 33 c of the GewO). One effect of this distinction is that pathological gamblers can have themselves blocked by national lotteries and casinos, but not in gaming arcades.

Diagnostic evaluation and screening instruments

Pathological gambling (PG) is currently categorized as a habit and impulse disorder. However, there are indications that in future, PG will be classified as a “non-substance related dependency” (e1) (Table 1).

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for “pathological gambling“ according to DSM-IV (e5) and ICD-10 (e1)—a brief comparison.

| DSM-IV Pathological gambling (312.31) | ICD-10 Pathological gambling (F63.0) |

| Diagnostic criteria | |

| Persistent and recurrent maladaptive gambling behavior as indicated by five (or more) of the following: | The disorder consists of frequent, repeated episodes of gambling that dominate the patient’s life to the detriment of social, occupational, material, and family values and commitments. |

|

Diagnostic criteria:

|

| Differential diagnosis | |

Distinct from

|

Exclusions:

|

NB: In the presence of three to four diagnoses of the DSM-IV, the term used is problematic gambling behavior

Important differential diagnoses for PG are gambling in the context of manic episodes and gambling problems in dissocial personality disorder. PG also needs to be differentiated from social and professional gambling.

In routine clinical practice, a short screening instrument is suitable in case of suspected pathological gambling. The treating physician can ask three questions based on the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS) in order to check whether PG was present in the preceding 12 months (3). The questionnaire is based on a secondary analysis of a large US population study. Stepwise discriminant analysis was used to determine the diagnostic criteria that distinguish pathological gamblers from healthy subjects. The sensitivity and specificity of the BBGS are high, but at present this instrument has not been validated in Germany (Box 1).

Box 1. Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS).

During the past 12 months, have you become restless, irritable, or anxious when trying to stop and (or) cut down on gambling?

During the past 12 months, have you tried to keep your family or friends from knowing how much you gambled?

During the past 12 months, did you have such financial trouble as a result of gambling that you had to get help with living expenses from family, friends, or welfare?

If your patient responded “yes” to one or several questions, it is likely that pathological gambling is present.

A screening instrument for clinical practice: the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen ([3]; https://divisiononaddictions.org/html/reprints/Gebauer_etal_2010.pdf)

A multitude of instruments is available for the purposes of thorough diagnostic evaluation, although no single unified standard has been agreed in Germany. The short questionnaire on gambling behavior by Petry and Baulig (e6, in German) or the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) by Lesieur and Blume (e7) are suitable examples; the latter is also being used by the German Federal Centre for Health Education for representative surveys (4, e8). However, using this method leads to overestimates of the proportion of pathological gamblers in the general population, since the questionnaire was originally developed for use in the clinical setting (5). For this reason, the obvious choice seems to be the list of criteria set out by Stinchfield (5), which decodes the current diagnostic criteria into 19 questions. This is available in a German translation, for downloading free of charge, from Bavaria’s state office for gambling addiction in the context of the practice handbook Glücksspiel (gambling) (6) (www.lsgbayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/lsg/Praxishandbuch_neu/36_Selbsttest_Gluecksspielsucht.pdf).

Types of gamblers and their characteristics

In addition to the diagnostic evaluation, several characteristics are relevant for the practicing physician. Among others, biological and cognitive factors play a part in the trajectory that takes a social gambler to developing into a pathological gambler (overview in [e9]). This also affects the motivation for seeking treatment or the setting required for treatment. Blaszczynski and Nower conclude from existing studies on factors of influence that there are three distinct types of gambler (7) (Box 2), which were confirmed by a recent meta-analysis (8).

Box 2. Types of gambler according to Blaszczynski and Nower (7).

Behaviorally conditioned problem gamblers: This group displays only minimal levels of psychopathology. The gamblers are mostly motivated to start treatment. Often, minimal interventions and counselling are sufficient.

Emotionally vulnerable problem gamblers: Premorbid anxiety and/or depression as well as poor coping and problem solving skills are characteristic of this group. Therefore, change is harder to achieve. The underlying vulnerability needs to be addressed and treated in the context of therapy.

Antisocial impulsivist problem gamblers: In contrast to the emotionally vulnerable problem gamblers, this group has a higher prevalence of antisocial personality disorders, attention deficit disorders, and a high degree of impulsivity. It is difficult to motivate such gamblers to start treatment; they show low compliance and have high dropout rates. Furthermore, they respond poorly to any form of intervention.

There are notable differences between the sexes: 70% to 80% of all pathological gamblers are male (9). In the advisory/treatment settings, women are underrepresented, with just 10% in outpatient treatment centers (e10). Female pathological gamblers receiving treatment in inpatient settings reported trauma during their childhood and adolescence, as well as severe and continued neglect, significantly more often than male gamblers (22% of women versus 11% of men), as well as physical (29% women versus 16% men) and sexual abuse (35% women versus 4% of men). Similarly, trauma during adulthood—such as muggings, rape, or life-threatening accidents—were found significantly more often in women (23% women versus 7% men), as was partner violence (15% women versus 1% men) (10). For those affected, gambling represents a distraction for the short term reduction of symptoms (10).

Prevalence

Six studies with prevalence estimates of PG currently exist for Germany (4, 9, 11, 12, e8, e11): according to these, 103 000 to 290 000 people are pathological gamblers (4, 11), another 103 000 to 350 000 display problematic gambling behaviors (4, 12). For both, this corresponds to some 0.2% to 0.6% of the population (12 month prevalence).

According to the Information System of the Federal Health Monitoring service of the Federal Statistical Office, 360 patients with a first diagnosis of PG were treated in hospitals in 2009, with the treatment covered by the statutory health insurers. Another 911 patients with a first diagnosis and 625 patients with a secondary diagnosis of PG were treated on an inpatient basis, with the treatment covered by the German statutory pension insurance scheme (e12). With regard to outpatient treatment, the data are sparse: In 2009, 33 patients with a first diagnosis of PG and 28 patients with a secondary diagnosis of PG received outpatient rehabilitation treatment (e12). For the number of patients treated by psychological psychotherapists in private practice, an extrapolation is available only for Bavaria (13). According to this, some 150 to 500 pathological gamblers were receiving psychotherapy in 2009. In the same year, according to statistics from the German center for addiction issues (Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen), 6090 pathological gamblers sought out outpatient care services in the whole of Germany—and this is not taking into account once-only contacts.

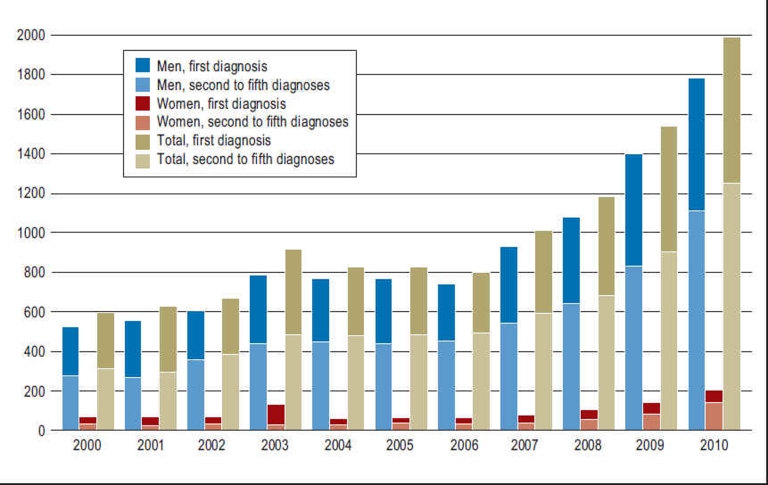

For 2010, the only available data are inpatient data from the German statutory pension insurance scheme. When main diagnoses and secondary diagnoses are considered, a rise of 29% is observed compared with the preceding year: 1249 patients with a first diagnosis and 729 patients with a secondary diagnosis of PG (F63.0) made use of inpatient services (Figure 1). The proportion of women with a first diagnosis of PG was 10.9%, and with a secondary diagnosis of PG was 8.1%.

Figure 1.

Inpatient services for medical rehabilitation

or other services for adult patients with a diagnosis of pathological gambling (ICD-10 F63.0) (2000–2010); differentiated by sex and by first diagnosis and further diagnoses (calculated from e12).

A large gap exists between the number of those affected and the proportion of those who seek treatment. Of the estimated 290 000 affected people (4), in 2009 scarcely 7400 patients were admitted to addiction services or hospitals for advice or treatment. This corresponds to 2.6% and excludes all those receiving treatment from psychotherapists.

Patient characteristics

Men and women differ from one another not only in terms of prevalence rates but also with regard to age distribution. Affected men tend to be younger; the age peak is 30–39 years. Affected women are on average 10 years older (e12).

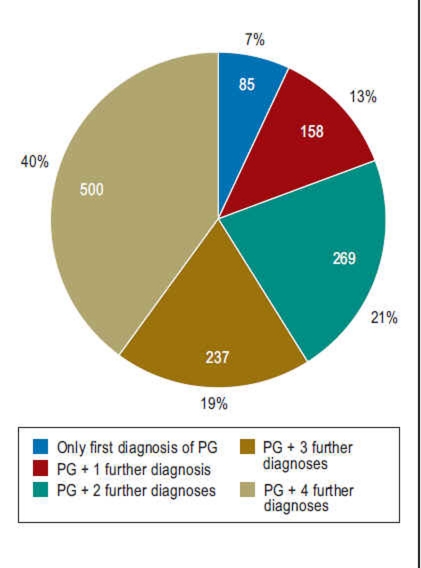

93% of patients (Figure 2) have comorbidities, mainly from the following list (in descending order of prevalence):

Figure 2.

Number of diagnoses in patients (n = 1249) diagnosed with pathological gambling (ICD-10 F63.0) (first diagosis) who received inpatient treatment for the purposes of medical rehabilitation or other services for adults from the Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme in 2010 (calculated from e12).

Mental and behavioral disorders

Disorders of the digestive system/metabolic disorders

Disorders of the musculoskeletal system/connective tissues

Disorders of the circulatory and respiratory system.

Women tend to have a greater number of secondary diagnoses compared to men. The proportion of women with five additional diagnoses is 48% whereas it is 39% in men. On the basis of the available data set we cannot comment on the combinations of comorbidities.

Comorbidities

Mental and behavioral disorders are the commonest comorbidities in pathological gamblers who are receiving treatment (e12). The additional diagnoses coded in this setting (multiple mentions possible) are mostly further mental disorders (81%). Furthermore, alcohol specific diagnoses are common and diagnoses related to medical substances/illicit drugs (11%).

Compared with pathological gamblers in the general population (e11), anxiety disorders and nicotine abuse/dependence are more common in those receiving inpatient treatment (14). Pathological gamblers in the general population, by contrast, are more prone to displaying personality disorders (Table 2).

Table 2. Lifetime prevalence of comorbid mental disorders in PG, in a comparison between the general population (e11) and a clinical sample (14).

| Comorbid mental disorders | Lifetime prevalence | |

| 7 | Pathological gamblers in the general population*1 (2011; n = 15 023) (e11) | Pathological gamblers in inpatient treatment*2 (2008; n = 101) (14) |

| Affective disorders | 63.1% | 61.4% |

| Anxiety disorders | 37.1% | 57.4% |

| Personality disorders | 35.2% | 27.7% |

| Tobacco-related disorders | 78.2% | 86.1% |

| Alcohol-related disorders | 54.9% (abuse and dependency) | 23.8% (abuse) 31.7% (dependency) |

| Substance-related disorders (excl. tobacco) | 44.3% (dependency only) | 60,4% (abuse and dependency) |

*1Data on gambling behavior in the general population were collected by means of telephone interviews. If the criteria for problematic or pathological gambling were met, in-depth clinical interviews (confirming comorbidities by means of M-CIDI and Skid II) were conducted.

*2In pathological gamblers receiving treatment, comorbid mental disorders were ascertained by means of standardized interviews (DIA-X, IPDE). PG, pathological gambling

Affective disorders

Pathological gambling and affective disorders often go hand in hand. Depression is diagnosed in more than half of pathological gamblers (e11). Furthermore, 32% of gamblers receiving treatment develop suicidal ideation and 17% actually attempt suicide (e13). Some authors postulate that affective disorders are the result of PG (14, 15). In other studies, no differences were found in the incidence of affective disorders before or after PG had developed (e14). This might be because the types of gamblers listed earlier display depressive symptoms at different times. In “emotionally vulnerable problem gamblers,” depression is present even before the onset of PG, whereas “problem gamblers with conditioned gambling behavior” often develop depression as a consequence of PG (7).

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders are also common in PG (14, 16). These are mostly present even before the PG and increase the risk of developing PG (7). They mostly are panic disorders (16).

Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma

15.5% of pathological gamblers in the general population have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (e11). In addition to fully expressed PSTD, high rates of trauma have been observed. In a patient study of pathological gamblers, 64% reported emotional trauma, 40.5% physical trauma, and 24.3% sexual trauma (17). By comparison, the following rates are reported for the general population: 14.9% emotional trauma, 12.0% physical trauma, and 12.5% sexual abuse of varying degrees of severity during childhood and adolescence (e15). Gambling women receiving treatment had significantly higher trauma rates than men (10). On average, pathological gamblers (without PTSD) reported four types of trauma with an average of 25 episodes of trauma each. 24% of persons with PTSD (without PG) display moderately risky gambling behavior and 9.5% problematic gambling behavior (e16).

Substance related disorders

A French cross sectional study that included patients from addiction treatment centers, found 6.5% pathological gamblers and 12% problematic gamblers among the people treated for alcohol addiction in the centers. All age groups were equally affected. Abstinence did not prompt a reduction in gambling problems (18).

Another study compared gamblers seeking treatment with regard to their smoking behavior. Regular smokers were found to be more beset with gambling problems, among others, than occasional smokers. They gambled more on weekdays, gambled higher sums, and had a stronger craving for gambling and a reduced feeling of being in control (e17). Altogether, 80% of pathological gamblers in the general population smoke (e11).

A US study of patients receiving methadone substitution treatment showed prevalence rates of 17.7% for pathological gambling and 11.3% displayed problematic gambling behavior (e18). The pathological gamblers did worse in terms of therapeutic success—that is, relating to their abstinence from cocaine or heroin during therapy and completion of therapy as planned. Another study that included inpatients with addiction disorders found the highest annual prevalence of PG, of 24%, for patients abusing cannabis, followed by 11.5% in those abusing cocaine. Alcohol and opiate abuse were of notably minor importance, with 4.0% and 4.8%, respectively (e19).

Personality disorders

A number of studies have reported high comorbidity rates with personality disorders (19), with prevalences roughly comparable to those found in psychiatric patients in general (e20). In pathological gamblers who are not undergoing treatment, borderline personality disorders have been observed particularly often (19). Gamblers undergoing treatment have also been found to have high rates of borderline personality disorders as well as histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders (e20). By contrast, a sample of pathological gamblers in Germany who received inpatient treatment often had obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, anxious (avoidant) personality disorder, or dependent personality disorder (14).

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Hyperkinetic disorders are also more common in pathological gamblers. People who have attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) into adulthood display more severe gambling behavior than persons without hyperkinetic disorders or those whose ADHD disappeared before adulthood (20). Adolescents with ADHD who were categorized in a recent cross sectional study into the dominant characteristics “attention deficit” and “hyperactivity-impulsivity in combination with attention deficit” gambled to an identical extent. The second group, however, displayed twice the rate of problematic gambling behavior (21).

Treatment with dopamine agonists in Parkinson’s disease

In recent years there have been repeated indications in the literature that treatment with dopamine agonists—for example, in Parkinson’s disease—can trigger impulse control disorders (22, 23, e21). A large cross sectional study from the US, which included more than 3000 patients with Parkinson’s disease from 46 treatment centers found such disorders in 13.6%. The proportion of pathological gamblers was 5.0% (24). Risk factors for developing an impulse control disorder are, in addition to intake of dopamine agonists (odds ratio [OR] = 2.7), being in a younger age group (OR = 2.5), an abnormal family history regarding PG (OR = 2.1), and positive smoking status (OR = 1.7). For the development of compulsive buying, PG, and hypersexuality, a dose-response effect has been observed. The higher the dosage the more common the corresponding disorders (25).

Interventions

For the treatment of PG thus far no clear preference for a particular psychotherapeutic approach has been identified (e22) and neither has a therapeutic program been found that meets current standards regarding the proof of effectiveness (e23); however, in Germany, the following relevant services are available to clinical practitioners. Currently there are a total of 25 hospitals that accept patients with a primary diagnosis of PG. Another 30 hospitals accept patients with PG as a secondary diagnosis. The hospitals are mostly located in Baden-Württemberg, North Rhine–Westphalia (9 hospitals each), Bavaria (8 hospitals), Lower Saxony (6 hospitals), Rhineland-Palatinate (6 hospitals), and Hesse (5 hospitals). The remaining federal states each have 1–2 of such hospitals, with the exception of Hamburg (Winter S et al.: Die Versorgungssituation pathologischer Glücksspieler – eine Experteneinschätzung [Services for pathological gamblers—an expert assessment]. Poster presentation at the 12th interdisciplinary conference on addiction medicine, Munich, July 2011). A suitable rehabilitation hospital can be found more easily by using LSG-Klinikexplorer (www.lsgbayern.de/index.php?id=243), which lists hospitals for PG for the whole of Germany, with different treatment focuses.

In the outpatient setting, services have been expanded since the GlüStV came into power. From 2007 to 2010 the German center for addiction issues (Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen, DHS) ran a nationwide early intervention project, and in individual states, coordination centers specializing in gambling addiction and specialized advisory centers have been set up (overview in [6]). Increasingly, advice centers also provide the option of outpatient rehabilitation. In Bavaria, for example, 14 advice centers have gained the required recognition status. This is reflected in the trends in the use of outpatient services: From 2004 to 2010, the numbers of those seeking treatment have more than doubled (e12).

The internet also provides support services, such as self-help forums (e.g., www.gamcare.org.uk, www.problemgambling.ca, www.gamblingselfchange.org) or an online service provided by the Federal Centre [sic] for Health Education (www.check-dein-spiel.de [in German]).

In view of the gambling options currently on offer, expansion and extension of support services are urgently needed, in order to raise awareness of problems and enable early intervention. Ideally, this would also mean that more of those affected could receive adequate advice and treatment earlier on.

Key Messages.

Pathological gamblers are a group of patients under intense psychological pressure and prone to comorbidities.

Patients with substance-related and affective disorders and anxiety and personality disorders should be interviewed about their gambling behavior.

Compared with the total number of pathological gamblers, only a small fraction is receiving treatment, similar to people misusing alcohol.

Awareness of screening instruments and types of gamblers enables physicians to more easily identify pathological gamblers in routine clinical practice.

Continuing medical educational events for doctors, as well as targeted early detection measures, can contribute to provide more pathological gamblers with adequate support than has been possible in the past.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr Birte Twisselmann.

The authors thank Thomas Bütefisch from the German Statutory Pension Insurance Scheme for the special evaluation F63.0.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Ministries and subordinate authorities in the Free State of Bavaria are active as operators or grant licenses for gambling. The Bavarian Academy for Addiction and Health Issues (BAS) is supported by funds from Bavaria’s State Ministry of the Environment and Public Health. The funding is not subject to any obligations on the authors’ part.

References

- 1.Grüsser SM, Albrecht U. Rien ne va plus - wenn Glücksspiele Leiden schaffen. Bern: Hans Huber. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Holst RJ, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ, Goudriaan AE. Why gamblers fail to win: A review of cognitive and neuroimaging findings in pathological gambling. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34:87–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebauer L, LaBrie RA, Shaffer HJ. Optimizing DSM-IV-TR classification accuracy: A brief biosocial screen for detecting current gambling disorders among gamblers in the general household population. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:82–90. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orth B, Töppich J, Lang P. Glücksspielverhalten in Deutschland 2007 und 2009. Ergebnisse aus zwei repräsentativen Bevölkerungsbefragung. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stinchfield R. Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) Addict Behav. 2002;27:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchner UG, Irles-Garcia V, Koytek A, Kroher M, Sassen M, editors. www.lsgbayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/lsg/Praxishandbuch_neu/36_Selbsttest_Gluecksspielsucht.pdf. München: Landesstelle Glücksspielsucht in Bayern; 2009. Praxishandbuch Glücksspiel. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaszczynski A, Nower L. A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction. 2002;97:487–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milosevic A, Ledgerwood DM. The subtyping of pathological gambling: A comprehensive review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:988–998. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buth S, Stöver H. Glücksspielteilnahme und Glücksspielprobleme in Deutschland: Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Repräsentativbefragung. Suchttherapie. 2008;9:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogelgesang M. Traumata, traumatogene Faktoren und pathologisches Glücksspielen. Psychotherapeut. 2010;55:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bühringer G, Kraus L, Sonntag D, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T, Steiner S. Pathologisches Glücksspiel in Deutschland: Spiel- und Bevölkerungsrisiken. Sucht. 2007;53:296–308. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sassen M, Kraus L, Bühringer G, Pabst A, Piontek D, Taqi Z. Gambling among adults in Germany: Prevalence, disorder and risk factors. Sucht. 2011;57:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraus L, Sassen M, Kroher M, Taqi Z, Bühringer G. Beitrag der Psychologischen Psychotherapeuten zur Behandlung pathologischer Glücksspieler: Ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie in Bayern. Psychotherapeutenjournal. 2011;2:152–156. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Premper V, Schulz W. Komorbidität bei Pathologischem Glücksspiel. Sucht. 2008;54:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou KL, Afifi TO. Disordered (pathologic or problem) gambling and Axis I psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:1289–1297. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petry NM, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Comorbidity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:564–574. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kausch O, Rugle L, Rowland DY. Lifetime histories of trauma among pathological Gamblers. Am J Addict. 2006;15:35–43. doi: 10.1080/10550490500419045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nalpas B, Yguel J, Fleury B, Martin S, Jarraus D, Craplet M. Pathological gambling in treatment-seeking alcoholics: a national survey in France. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:156–160. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bagby R M, Vachon D D, Bulmash E L, Toneatto T, Quilty LC. Personality disorders and pathological gambling: a review and re-examination of prevalence rates. J Pers Disord. 2008;22:191–207. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breyer JL, Botzet AM, Winters KC, Stinchfield PD, August G, Realmuto G. Young adult gambling behaviors and their relationship with the persistence of ADHD. J Gambl Stud. 2009;25:227–238. doi: 10.1007/s10899-009-9126-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faregh N, Derevensky J. Gambling behavior among adolescents with attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. J Gambl Stud. 2011;27:243–256. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crockford D, Quickfall J, Currie S, Furtado S, Suchowersky O, el-Guebaly N. Prevalence of problem and pathological gambling in Parkinson’s disease. J Gambl Stud. 2008;24:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s10899-008-9099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voon V, Thomsen T, Miyasaki JM, et al. Factors associated with dopaminergic drug-related pathological gambling in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:212–216. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN, Siderowf AD, Stacy M, Voon V, Whetteckey J, Wunderlich GR, Lang AE. Impulse control disorders in parkinson disease. A Cross-Sectional Study of 3090 Patients. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:589–595. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim JW, Cho J, Lee WY. Association between the dose of dopaminergic medication and the behavioral distubances in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Dilling H, editor. 5th revised edition. Göttingen: Huber; 2010. Taschenführer zur ICD-10-Klassifikation psychischer Störungen. [Google Scholar]

- e2.Staatsvertrag zum Glücksspielwesen in Deutschland (Glücksspielstaatsvertrag) www.lsgbayern.de/fileadmin/user_upload/lsg/Praxishandbuch_neu/54_Gesetze_Verordnungen.pdf.

- e3.Gewerbeordnung. www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/gewo/gesamt.pdf.

- e4.Verordnung über Spielgeräte und andere Spiele mit Gewinnmöglichkeit (Spielverordnung) www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/spielv/gesamt.pdf.

- e5.Saß H, Wittchen H-U, Zaudig M, editors. 2nd edition. Göttingen: Huber; 1998. Diagnostische Kriterien des Diagnostischen und Statistischen Manuals Psychischer Störungen DSM-IV. [Google Scholar]

- e6.Petry J. Weinheim. Psychologie Verlags Union; 1996. Psychotherapie der Glücksspielsucht. [Google Scholar]

- e7.Lesieur HR, Blume S. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1184–1188. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Orth B, Töppich J, Lang P. Glücksspielverhalten und problematisches Glücksspielen in Deutschland 2007. Ergebnisse einer Repräsentativbefragung. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- e9.Hodgins DC, Stea JN, Grant JE. Gambling disorders. Lancet. 2011;378:1874–1884. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62185-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Pfeiffer-Gerschel T, Kiepke I, Steppan M. Deutsche Suchthilfestatistik. www.suchthilfestatistik.de. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- e11.Meyer C, Rumpf HJ, Kreuzer A, et al. Pathologisches Glücksspielen und Epidemiologie (PAGE): Entstehung, Komorbidität, Remission und Behandlung. Endbericht. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- e12.Sonderauswertung F63.0 der Deutschen Rentenversicherung Bund für die Bayerische Akademie für Sucht- und Gesundheitsfragen. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- e13.Petry NM, Kiluk BD. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:462–469. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000022447.27689.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Hodgins DC, Peden N, Cassidy E. The association between comorbidity and outcome in pathological gambling: a prospective follow-up of recent quitters. J Gambl Stud. 2005;21:255–271. doi: 10.1007/s10899-005-3099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Häuser W, Schmutzer G, Brähler E, Glaesmer H. Maltreatment in childhood and adolescence—results from a survey of a representative sample of the German population. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:287–294. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Najavits L, Meyer T, Johnson K, Korn D. Pathological gambling and posttraumatic stress disorder: A study of the co-morbidity versus each alone. J Gambl Stud. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9230-0. online first 30.12.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Petry N M, Oncken C. Cigarette smoking is associated with increasing severity of gambling problems in treatment-seeking gamblers. Addiction. 2002;97:745–753. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Ledgerwood DM, Downey KK. Relationship between problem gambling and substance use in methadone maintenance population. Addict Behav. 2002;27:483–491. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Toneatto T, Brennan J. Pathological gambling in treatment-seeking substance abusers. Addict Behav. 2002;27:465–469. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Blaszczynski A, Steel Z. Personality disorders among pathological gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 1998;14:51–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1023098525869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Bostwick JM, Hecksel KA, Stevens SR, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE. Frequency of new-onset pathological compulsive gambling or hypersexuality after drug treatment of idiopathic Parkinson disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:310–316. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60538-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Winters KC, Kushner MG. Treatment issues pertaining to pathological gamblers with a comorbid disorder. J Gambl Stud. 2003;19:261–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1024203403982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Westphal JR. Are the effects of gambling treatment overestimated? Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2007;5:56–79. [Google Scholar]