Abstract

Background

The subtype of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) called minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) is highly prevalent (22–74%) among patients with liver dysfunction. MEH is defined as HE without grossly evident neurologic abnormalities, but with cognitive deficits that can be revealed by psychometric testing.

Methods

This article is based on relevant original publications and reviews in English and German (1970–2011) that were retrieved by a selective key-word-based search in the Medline and PubMed databases.

Results

Despite its mild manifestations, MHE impairs patients’ quality of life and their ability to work. It impairs driving ability and is associated with a higher rate of motor vehicle accidents. Furthermore, patients with MHE fall more often and are more likely to undergo progression to overt HE. The main pathophysiological mechanism of MHE is hyperammonemia leading to astrocyte dysfunction. Psychometric tests are the standard instruments for establishing the diagnosis; further, supportive diagnostic tools include neurophysiological tests and imaging studies. Recent randomized and controlled trials have revealed that treatment with lactulose or rifaximin therapy improves the quality of life of patients with MHE. Rifaximin was also found to improve driving performance in a simulator. A combination of these two drugs prevents the recurrence of episodic HE over a 6-months follow-up period. Moreover, small-scale trials have revealed that some dietary supplements can improve the cognitive deficits of MHE.

Conclusion

Clinical trials have shown that patients with MHE and patients who have had an episode of overt HE in the past can benefit from drug treatment.

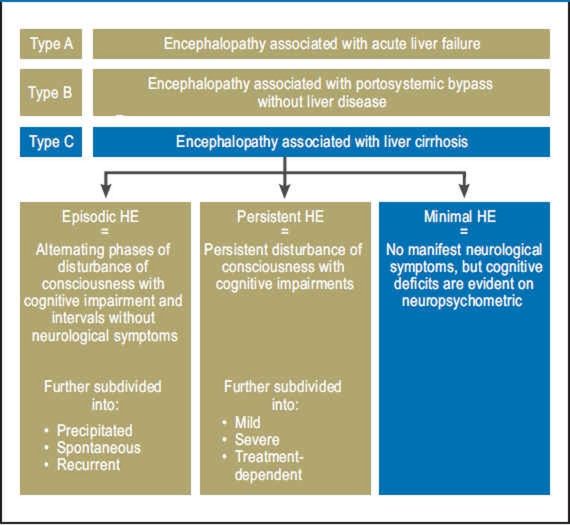

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a potentially reversible, metabolically caused disturbance of central nervous system function that occurs in patients with acute or chronic liver disease. It encompasses a broad spectrum of neurological symptoms of varying severity and is classified according to clinical symptoms (Table 1) or etiology (Figure 1). Minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE), previously known as subclinical or latent hepatic encephalopathy, is at the beginning of this spectrum. It is defined as HE without symptoms on clinical/neurological examination, but with deficits in some cognitive areas that can only be measured by neuropsychometric testing (1). The areas with impairments are attention, visuospatial perception, speed of information processing, especially in the psychomotor area, fine motor skills, and short-term memory (2). MHE has a high prevalence among patients with liver cirrhosis (22% to 74%) (e1) and also occurs in patients with noncirrhotic liver disease such as portal vein thrombosis (e2) or portosystemic shunt (e3). However, the true number of patients with MHE is unknown, firstly because the diagnostic criteria in use around the world are not entirely uniform, and secondly because MHE often remains undiagnosed due to the lack of evident symptoms (e4). However, numerous studies have shown that, although the neurological symptoms are slight, affected patients are markedly impaired in their quality of life and ability to work (3, 4). In addition, in two retrospective studies, patients with liver cirrhosis and MHE had significantly more driving accidents than those without MHE (6, e5). The reasons were more frequent driving errors (speeding, illegal turns) as shown by one study using a driving simulator (e6), a greater tendency to fatigue at the wheel (e7), and subjective overestimation of their own driving skills (e8). Other studies have shown that patients with MHE suffer from falls (5) and from the development of episodic HE more frequently (7, e9). Some studies have even identified MHE as an independent predictor of survival in patients with liver cirrhosis (8, e10). At the same time, current randomized controlled trials (RCTs) indicate that treating MHE leads to an improvement in cognitive abilities (9, 10) and driving performance (11). This review presents the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and options for treatment of MHE.

Table 1. Semiquantitative grading of mental status in hepatic encephalopathy using the West Haven criteria (modified from Conn et al. [e32]). Grade 0 corresponds to MHE.

| Level of consciousness | Neuropsychiatric symptoms | Neurological symptoms | |

| Grade 0 = MHE | Normal | aggression, marked disorientation to time and place | None |

| Grade 1 | Slight mental slowing down | Eu-/dysphoria, irritability and anxiety, shortened attention span | Fine motor skills disturbed (impaired ability to write, finger tremor) |

| Grade 2 | Increased fatigue, apathy or lethargy | Slight personality disorder, slight disorientation to time and place | Flapping tremor, ataxia, slurred speech |

| Grade 3 | Somnolence | Aggression, marked disorientation to time and place | Rigor, clonus, asterixis |

| Grade 4 | Coma | – | Signs of increased intracranial pressure |

MHE, minimal hepatic encephalopathy

Figure 1.

Nomenclature of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (1).

Method

PubMed and Medline were searched for original and review articles using a combination of the search terms “minimal hepatic encephalopathy” plus “ammonia,” “lactulose,” “psychometry,” or “rifaximin.” Publications in English and German from the years 1970 to 2011 were evaluated. The reference lists of these articles were also searched for further publications.

Pathogenesis

Ammonia

Ammonia is of central importance in the pathogenesis of HE. Under physiological conditions ammonia is primarily cleared by the synthesis of urea in the liver. If the liver is functionally impaired or a portosystemic shunt is present, this function is compromised and the extrahepatic metabolization of ammonia by the brain and musculature becomes more important (e11). Accumulation of ammonia in the brain of patients with MHE has been shown directly by positron emission tomography (PET) (12). Astrocytes are the only cells in the brain that can fix ammonia, through the formation of glutamine (e11). The intracellular glutamine concentration in the astrocytes rises with ammonia levels in the blood, and causes the cells to swell through the osmosis. This leads overall to the development of low-grade brain edema, which correlates with deterioration in psychometric tests (e12). The close association between brain edema and impaired liver function is also shown by the fact that brain edema and the cognitive impairments are reversible by liver transplantation (e12).

Other factors

Disequilibrium of the gut flora with fecal overgrowth by urease-forming bacteria has been observed in patients with MHE, and therapeutic intervention led to an improvement of this disequilibrium and of psychometric test results (14). In addition, bilateral manganese deposits have been found in the globus pallidus in patients with HE (e13). Both manganese and ammonia are believed to increase the expression of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in the brain (e14). These receptors regulate the production of neurosteroids and are present in increased density in the brain of patients with MHE (e15). Through increased synthesis of neurosteroids, which function as positive regulators of GABA-A receptors, the GABAergic tone in the brain is increased.

Diagnosis

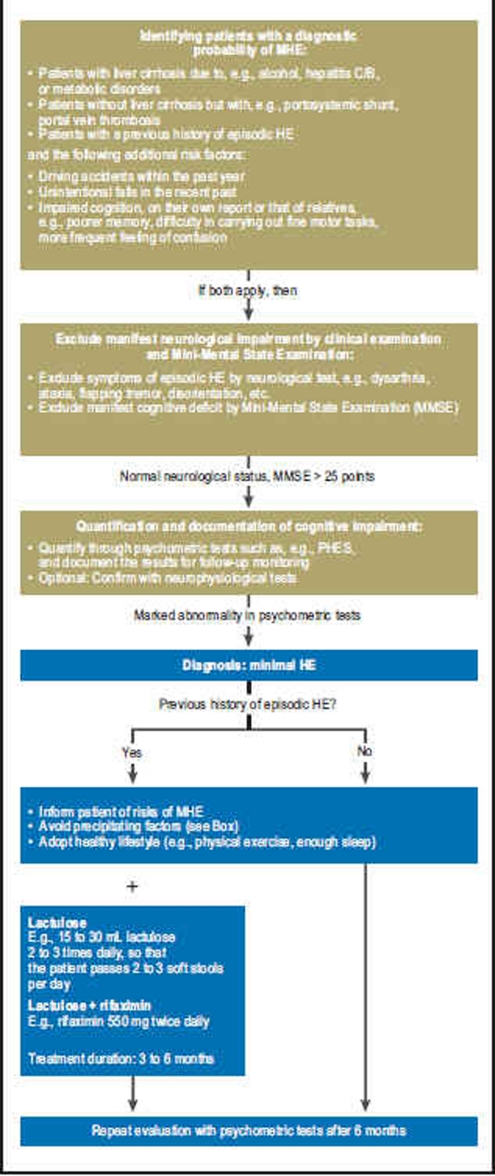

A survey of the American Society for the Study of Liver Diseases revealed that the majority of doctors regard MHE as a significant clinical problem, but only half of those actually tested their patients for MHE (e4). The West Haven criteria for clinical stratification of HE (Table 1), which are in common use, assume manifest neurological symptoms and are therefore of limited suitability in MHE. Although there is international consensus that psychometric tests are the gold standard in the diagnosis of MHE (1), no agreement exists as to what combination of tests should be carried out, and what the threshold value is at which MHE may be reliably diagnosed. This central problem is reflected in the varying reported prevalences for the disease, which range from 22% to 74% depending on which tests are chosen and where the threshold is defined (e1). A general approach to the diagnosis and treatment of MHE based on Ferenci et al. (1) is shown in Figure 2. First, obvious neurological symptoms and cognitive impairment should be ruled out. In addition to the neurological examination, the test that has proved most useful for this purpose is the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The MMSE is a widely used screening test for the diagnosis of dementia and examines the most important basic cognitive abilities (e16) (Table 2). If both the clinical examination and the MMSE yield normal results, the next step is to quantify any latent cognitive deficits through psychometric testing. Neurophysiological tests and imaging techniques exist to complement these, but are mainly used in experimental settings.

Figure 2.

Suggested procedure for diagnosis and treatment of MHE.

MHE, minimal hepatic encephalopathy,

PHES, psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score

Table 2. Mini Mental State Examination (modified from Folstein et al. [e16, e33]). In most studies episodic HE and severe cognitive impairment were ruled out by a score above 25 (10, 11).

| Score | Parameter |

| Orientation | |

| 5 | Which year, season, month is it? |

| 5 | What date is it today, what day is it? |

| Where are we (country, state, town/city, doctor’s office/hospital)? Which floor are we on? | |

| One point for each correct answer | |

| Registration | |

| 3 | Repeat three words |

| (e.g., lemon, bowl, ball); | |

| repeat until the patient has learned the words | |

| Attention and calculation | |

| 5 | Starting from 100, subtracting 7 each time (93, 86, 79, 72, 65); |

| one point for every correct answer; | |

| stop after five answers; | |

| another option: spell a five-letter word backwards (e.g., world) | |

| 3 | Recall:Ask for the words repeated above: one point for each word |

| Language and understanding Naming: | |

| 1 | What is this? (e.g., show pencil) |

| 1 | What is this? (e.g., show watch) |

| 1 | Repeat: “No ifs, ands or buts.” |

| Carrying out a three-part order | |

| 3 | e.g., “Please take this paper in your right hand, fold it in half, and put it on the floor.” One point for each part |

| Reading and performing | |

| 1 | (prepare on a separate paper) |

| “Close your eyes”. One point for both together | |

| 1 | Writing a sentence of the patient’s choice that contains a subject and a predicate and makes sense (do not dictate/ the sentence must be spontaneous/ spelling mistakes do not affect scoring) |

| 1 | Copying: |

|

|

| one point if all sides and angles are correct and the overlaps form a rectangle | |

| Have the patient copy the following figure | |

| Score | < 25 points = impairment suggesting disease |

| < 20 points = slight to moderate dementia | |

| < 10 points = severe dementia |

Ammonia concentration

In episodic HE, the venous ammonia concentration correlates with the severity of neurological impairment (15) and may be used in the differential diagnosis. Ammonia concentrations are less important in the diagnosis of MHE because they do not correlate with the degree of neurological dysfunction (13). In addition, correct measurement of the ammonia concentration requires a venous blood sample obtained without using a tourniquet and immediate laboratory analysis within 20 minutes, which in clinical routine, especially in a doctor’s office, is rarely possible (15). The ammonia concentration is also influenced by factors such as renal function, nicotine consumption, and muscle mass.

Psychometric tests

The Psychometric HE Score (PHES) consists of a series of psychometric tests and was conceived specifically for diagnosing MHE (2). It comprises the number connection test (NCT), the line-tracing test, and the number–symbol test, and takes a total of 20 to 25 minutes (Table 3). Most studies of MHE use the PHES or a selection of its constituent tests. The great advantage of this test is that for some countries, including Germany, comparative data exist from the normal population. The disadvantages of the test are the occurrence of learning effects, which limits repeatability, and the strong emphasis on fine motor skills. There are also differences as to where the border between normal and pathological should be drawn.

Table 3. Psychometric tests recommended for diagnosing minimal hepatic encephalopathy. The lower the overall score, the better the cognitive performance (modified from Ferenci et. al [1]).

| Test | Description |

| Number connection test A (NCT-A) | Randomly dispersed numbers are to be connected with each other in serial order as quickly as possible. |

| Number connection test B (NCT-B) | Randomly dispersed numbers and letters are to be connected in alternating series (1-A-2-B…) as quickly as possible. |

| Line copying test | A given line is to be traced as quickly as possible. |

| Digit–symbol test | The patient receives a sheet of paper on which each digit from 1 to 9 is assigned a symbol. Under each digit the patient is to write down the corresponding symbol within a given time. |

| Mosaic test | Cubes with various designs on each face are to be placed within a given time such that the upper faces form a particular design. |

Neurophysiological tests

To increase objectivity and reproducibility, various neurophysiological tests have been developed. Determination of the critical flicker frequency is based on the assumption that the glial cells of the retina are subject to the same functional impairment as the astrocytes in the brain. A light impulse with an initial frequency of 60 Hz is presented to the patient, who perceives it as a constant light. The frequency is then reduced by 0.1 Hz steps until the patient first perceives the light as flickering. This frequency is the critical flicker frequency. It correlates positively with psychometric test results and is not affected by gender or education, but may be affected by age (16, e17).

Another neurophysiological test is the electroencephalogram (EEG). Changes in the spectral EEG and in the discharge of visual evoked late potentials (P300 wave) are believed to have a higher sensitivity than psychometric tests and to have prognostic significance for progression to episodic HE (e18, e19). Although neurophysiological tests have considerable advantages, their use is limited by the high cost of acquiring the technical apparatus and analyzing the results. For this reason they are mainly used in experimental studies.

Imaging techniques

Various magnetic resonance techniques show pathological changes in patients with MHE. T1-weighted MRI shows a hyperintense signal in the basal ganglia (globus pallidus and substantia nigra), which is interpreted as due to manganese deposits (e20). Although the hyperintensity is not quantitatively correlated to the severity of HE, it does disappear after liver transplantation (e20). Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy, changes can also be demonstrated in the relationship between myoinositol and creatine in patients with MHE (e21). It is assumed that the osmotically active myoinositol is secreted from the cell in order to compensate for the swelling caused by glutamine. Magnetization transfer measurements have shown low-grade brain edema in patients with MHE (e22). Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and PET show changes in blood flow that correlate with psychometric test results (17, e23).

Treatment

Unlike for episodic HE, there are only a few RCTs with small case numbers on the treatment of MHE (Table 4). The effects of lactulose and rifaximin are the best investigated. So far, RCTs have shown a positive effect of treatment on cognitive abilities, quality of life (9, 10), and driving ability (11); its effect on patients’ ability to work or risk of falling remains unproven. The duration of treatment and choice of medication also remain unclear. Most treatment approaches derive from experience with episodic HE. Since deterioration of cognitive function in patients with liver cirrhosis is primarily triggered by precipitating factors (e24), consistently avoiding these factors is also paramount for patients with MHE (Box).

Table 4. Existing studies on the treatment of MHE.

| Study | n | Study design | Treatment | Duration of treatment | Diagnostic tests and outcome tests | Findings |

| Watanabe et al. 1997 (20) | 36 | RCT | Lactulose (n = 22) vs. no treatment (n = 14) | 8 weeks | Psychometric tests |

|

| Dhiman et al. 2000 (19) | 26 | RCT | Lactulose (n = 14) vs. no treatment (n = 12) | 3 months | Psychometric tests |

|

| Prasad et al. 2007 (9) | 61 | RCT | Lactulose (n = 31) vs. no treatment (n = 30) | 3 months | Psychometric tests, assessment of quality of life using SIP score |

|

| Bajaj et al. 2011 (11) | 42 | RCT | Rifaximin (n = 21) vs. placebo (n = 21) | 8 weeks | Psychometric tests, assessment of quality of life using SIP score, driving ability measured at the simulator, blood concentation of ammonia, inflammation parameters, MELD score |

|

| Sidhu et al. 2011 (10) | 94 | RCT | Rifaximin (n = 49) vs. placebo (n = 45) | 8 weeks | Psychometric tests, assessment of quality of life using SIP score |

|

| Malaguarnera et al. 2008 (24) | 115 | RCT | L-Acetyl carnitine (n = 60) vs. placebo (n = 55) | 10 weeks | Psychometric tests, EEG, lab tests (ammonia, transaminases) |

|

| Liu et al. 2004 (14) | 55 | RCT | Fermentable fiber (n = 20) vs. probiotic combination (non-urease-producing bacteria and fermentable fiber) (n = 20) vs. placebo (n = 15) | 30 days | Psychometric tests, quantitative bacterial stool analysis, stool pH value, blood concentrations of ammonia and endotoxins |

|

| Bajaj et al. 2008 (25) | 35 | RCT | Probiotic yoghurt (n = 17) vs. no treatment (n = 8) | 60 days | Psychometric tests, assessment of quality of life using SF-36 |

|

RCT: randomized, controlled study; SIP: Sickness Impact Profile (questionnaire assessing health-related quality of life; the lower the value, the better the quality of life); SF-36: short form 36 (instrument for assessing health-related quality of life); MHE: minimal hepatic encephalopathy; MELD: model for end-stage liver disease; CI: confidence interval

Box. Precipitating factors for development of MHE and episodic HE.

Gastrointestinal bleeding

Excessive protein

Hyperkalemia/hyponatremia

Constipation

Sedatives and tranquilizers

Electrolyte imbalances

Infections

Trauma

Dehydration

Uremia

MHE, minimal hepatic encephalopathy

HE, hepatic encephalopathy

Nonabsorbable disaccharides

The nonabsorbable disaccharides lactulose and lactilol are those for which the most comprehensive data is available, because both of these substances have been in clinical use for a long time. In consequence, lactulose is regarded as the first-line therapy for HE (18). Besides their laxative effect, nonabsorbable disaccharides reduce the synthesis and uptake of ammonia by lowering the pH of the colon and also reducing the uptake of glutamine from the gut (e25). It has been shown in several studies that treatment with lactulose significantly improves the performance of patients with MHE in psychometric tests, which is associated with a rise in quality of life (9, 19, 20). Lactulose is also superior to placebo in preventing episodic HE (recurrence in 19.6% of patients in the lactulose group vs. 46.8% in the placebo group, P = 0.001; duration of follow-up: 14 months) (21). The usual oral dose is 15 to 30 mL twice daily, in order to achieve a soft stool several times a day. A course of treatment should continue for at least 3 to 6 months. The adverse effects of the treatment are alteration of taste perception and bloating. Overdosing causes diarrhea which can result in severe dehydration and hyponatremia, which lead to worsening of HE (e26).

Antibiotics

The aim of antibiotic therapy is to reduce ammonia production in the gut. Neomycin was the first antibiotic to be used in the treatment of HE and appears to be as effective as lactulose (e27). Despite their low absorption, the use of macrolides has been reduced in recent years because of their marked oto- and nephrotoxicity, the more so because these adverse effects are particularly serious in patients with reduced liver function. One alternative that is being increasingly used is rifaximin. Rifaximin is an oral antibiotic that is only minimally absorbed in the gut and therefore has a very low adverse effect profile. Although it has been in use since 1987, particularly in the treatment of enteritis, no clinically significant resistance has been observed so far. Rifaximin has been licensed in the USA since 2010 for treatment of HE, and licensing is planned for Germany in 2012. Taking rifaximin improves psychometric test results, quality of life, and driving ability in patients with MHE (10, 11). The exact changes in the effect sizes are presented in Table 4. Bass et al. were able to show in a large study that long-term therapy with rifaximin plus lactulose in patients who had a history of HE gave better protection against renewed episodic HE than did the placebo treatment (hazard ratio with rifaximin: 0.42; 95% confidence interval 0.28 to 0.64; P < 0.001) (22).

Nutritional therapy/nutrition supplementation

The question whether increasing or restricting protein intake is beneficial remains under debate, since under physiological conditions, amino acids are almost fully absorbed in the ileum and consequently contribute little to ammonia production in the colon. It has nevertheless been postulated that excessive protein intake could provoke an increase in blood ammonia levels due to physiological malabsorption. On the other hand, reducing protein intake decreases body muscle mass and hence the ability to absorb ammonia extrahepatically. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) currently recommends on a purely empirical basis a protein intake of 1 to 1.2 g/kg body weight for patients with HE, with vegetable proteins being preferred to animal proteins (23). In one RCT, oral intake of branched-chain amino acids improved the psychometric test results of patients with HE (e28). In addition, there are indications that oral intake of L-ornithine aspartate, a substrate of the urea cycle, improves the cognitive abilities of patients with HE of varying severity (e29). One further potential candidate for treating MHE is L-acetyl carnitine. Two recent RCTs show improvement of cognitive function and reduction of ammonia concentrations (24, e30). Zinc deficiency is often seen in patients with liver cirrhosis and impairs the metabolization of ammonia (e31). Although the effect of zinc supplementation in HE is not entirely clear, patients with manifest zinc deficiency should receive supplements (18). Probiotics such as yoghurt can have a beneficial effect on the bacterial microflora in terms of lowering ammonia production. In two RCTS, probiotics have led to a significant improvement in MHE (14, 25). The effect of a combination of the above substances has not yet been adequately investigated.

Summary

The borderline between normal or acceptable findings and pathological findings—that is, those that are a threat to health—is fluid in MHE. The problem is that MHE can be a risk to other people, e.g., when it leads to inadequate reactions when driving. Unfortunately this is not easy to measure. In the spectrum of the heterogeneous general population, and given the physiological fluctuations in attention status, patients with MHE are often difficult to identify. For the physician, therefore, the question is whether patients with impaired liver function—e.g., patients suffering from liver cirrhosis and MHE—require a specific treatment. If a patient has never had an episode of HE, we believe that the most important step is to inform the patient about the potential risks. Lifestyle changes, with a balanced diet (not too rich in protein), exercise, enough sleep, and abstinence from alcohol and sedativa, are probably the most appropriate way to proceed. Once episodic HE has been documented, specific medical treatments recommended by the specialist societies for episodic HE should be added to the above changes on a preventative basis. Monotherapy with lactulose or (depending on the individual risk potential) a combination of lactulose with rifaximin should be chosen. Patient compliance is absolutely essential and should be ensured, e.g., by including relatives in the treatment program.

Key Messages.

Minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) is a subtype of hepatic encephalopathy without manifest neurological symptoms, but with cognitive deficits shown by psychometric tests. Patients with impaired liver function and MHE have driving accidents more often than those without MHE. This is because they commit more driving errors, suffer fatigue at the wheel more quickly, and overestimate their own driving skills.

MHE reduces the quality of life and ability to work of affected patients. Patients with MHE fall more often and develop episodic HE more frequently. MHE is also a negative predictor for survival in patients with liver cirrhosis.

MHE is primarily diagnosed using psychometric tests; the diagnosis can be confirmed by additional neurophysiological tests or imaging techniques.

In recent randomized, controlled studies, lactulose and rifaximin have improved the quality of life of patients with MHE; rifaximin also has a positive effect on their driving skills. Long-term therapy with lactulose and rifaximin plus lactulose significantly reduces the recurrence of episodic HE in patients who have previously had HE.

On the basis of existing studies, the best recommendation for primary treatment of MHE is consistent avoidance of risk factors and leading a healthy lifestyle. For patients with MHE who have had episodic HE in the past, drug therapy with lactulose or a combination of rifaximin and lactulose is recommended.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy—definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology. 2002;35:716–721. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, Ruckert N, Hecker H. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34:768–773. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schomerus H, Hamster W. Quality of life in cirrhotics with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2001;16:37–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1011610427843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groeneweg M, Quero JC, De Bruijn I, et al. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy impairs daily functioning. Hepatology. 1998;28:45–49. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roman E, Cordoba J, Torrens M, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is associated with falls. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:476–482. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Schubert CM, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is associated with motor vehicle crashes: the reality beyond the driving test. Hepatology. 2009;50:1175–1183. doi: 10.1002/hep.23128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero-Gomez M, Boza F, Garcia-Valdecasas MS, Garcia E, Aguilar-Reina J. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy predicts the development of overt hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2718–2723. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amodio P, Del Piccolo F, Marchetti P, et al. Clinical features and survivial of cirrhotic patients with subclinical cognitive alterations detected by the number connection test and computerized psychometric tests. Hepatology. 1999;29:1662–1667. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad S, Dhiman RK, Duseja A, Chawla YK, Sharma A, Agarwal R. Lactulose improves cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis who have minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:549–559. doi: 10.1002/hep.21533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Mishra BP, Sood A, Chhina RS, Soni RK. Rifaximin improves psychometric performance and health-related quality of life in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy (the RIME Trial) Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:307–316. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Wade JB, et al. Rifaximin improves driving simulator performance in a randomized trial of patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:478–487. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockwood AH, Yap EW, Wong WH. Cerebral ammonia metabolism in patients with severe liver disease and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:337–341. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shawcross DL, Wright G, Olde Damink SW, Jalan R. Role of ammonia and inflammation in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2007;22:125–138. doi: 10.1007/s11011-006-9042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q, Duan ZP, Ha DK, Bengmark S, Kurtovic J, Riordan SM. Synbiotic modulation of gut flora: effect on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2004;39:1441–1449. doi: 10.1002/hep.20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong JP, Aggarwal A, Krieger D, et al. Correlation between ammonia levels and the severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med. 2003;114:188–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kircheis G, Wettstein M, Timmermann L, Schnitzler A, Haussinger D. Critical flicker frequency for quantification of low-grade hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2002;35:357–366. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lockwood AH, Weissenborn K, Bokemeyer M, Tietge U, Burchert W. Correlations between cerebral glucose metabolism and neuropsychological test performance in nonalcoholic cirrhotics. Metab Brain Dis. 2002;17:29–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1014000313824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blei AT, Cordoba J. Hepatic Encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1968–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhiman RK, Sawhney MS, Chawla YK, Das G, Ram S, Dilawari JB. Efficacy of lactulose in cirrhotic patients with subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1549–1552. doi: 10.1023/a:1005556826152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe A, Sakai T, Sato S, et al. Clinical efficacy of lactulose in cirrhotic patients with and without subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 1997;26:1410–1414. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.pm0009397979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma BC, Sharma P, Agrawal A, Sarin SK. Secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy: an open-label randomized controlled trial of lactulose versus placebo. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:885–891. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1071–1081. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plauth M, Cabre E, Riggio O, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malaguarnera M, Gargante MP, Cristaldi E, et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine treatment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3018–3025. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, et al. Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1707–1715. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, Sharma BK, Sarin SK, Chawla YK, Butterworth R, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: consensus statement of a working party of the Indian National Association for Study of the Liver. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1029–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Sharma P, Sharma BC, Puri V, Sarin SK. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1406–1412. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Sarin SK, Nundy S. Subclinical encephalopathy after portosystemic shunts in patients with non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis. Liver. 1985;5:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1985.tb00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Bajaj JS, Etemadian A, Hafeezullah M, Saeian K. Testing for minimal hepatic encephalopathy in the United States: An AASLD survey. Hepatology. 2007;45:833–834. doi: 10.1002/hep.21515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Saeian K. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a vehicle for accidents and traffic violations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1903–1909. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Varma RR, Franco J, Binion DG, et al. Navigation skill impairment: Another dimension of the driving difficulties in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2008;47:596–604. doi: 10.1002/hep.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Zadvornova Y, Martin E, Schubert CM, Gibson DP, et al. The effect of fatigue on driving skills in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:898–905. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Hammeke TA. Patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy have poor insight into their driving skills. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1135–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.025. quiz 1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Das A, Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, Verma M, Naik SR. Prevalence and natural history of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:531–535. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Dhiman RK, Kurmi R, Thumburu KK, Venkataramarao SH, Agarwal R, Duseja A, et al. Diagnosis and prognostic significance of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis of liver. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2381–2390. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Cooper AJ, Plum F. Biochemistry and physiology of brain ammonia. Physiol Rev. 1987;67:440–519. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1987.67.2.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Cordoba J, Alonso J, Rovira A, Jacas C, Sanpedro F, Castells L, et al. The development of low-grade cerebral edema in cirrhosis is supported by the evolution of (1)H-magnetic resonance abnormalities after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;35:598–604. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Rose C, Butterworth RF, Zayed J, Normandin L, Todd K, Michalak A, et al. Manganese deposition in basal ganglia structures results from both portal-systemic shunting and liver dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:640–644. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e14.Ahboucha S, Butterworth RF. The neurosteroid system: implication in the pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e15.Cagnin A, Taylor-Robinson SD, Forton DM, Banati RB. In vivo imaging of cerebral „peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites“ in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Gut. 2006;55:547–553. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.075051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e16.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. „Mini-mental state“ A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e17.Romero-Gomez M, Cordoba J, Jover R, del Olmo JA, Ramirez M, Rey R, et al. Value of the critical flicker frequency in patients with minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2007;45:879–885. doi: 10.1002/hep.21586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e18.Amodio P, Marchetti P, Del Piccolo F, de Tourtchaninoff M, Varghese P, Zuliani C, et al. Spectral versus visual EEG analysis in mild hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1334–13344. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e19.Saxena N, Bhatia M, Joshi YK, Garg PK, Tandon RK. Auditory P300 event-related potentials and number connection test for evaluation of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis of the liver: a follow-up study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:322–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e20.Weissenborn K, Ehrenheim C, Hori A, Kubicka S, Manns MP. Pallidal lesions in patients with liver cirrhosis: clinical and MRI evaluation. Metab Brain Dis. 1995;10:219–231. doi: 10.1007/BF02081027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e21.Naegele T, Grodd W, Viebahn R, Seeger U, Klose U, Seitz D, et al. MR imaging and (1)H spectroscopy of brain metabolites in hepatic encephalopathy: time-course of renormalization after liver transplantation. Radiology. 2000;216:683–691. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se27683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e22.Kale RA, Gupta RK, Saraswat VA, Hasan KM, Trivedi R, Mishra AM, et al. Demonstration of interstitial cerebral edema with diffusion tensor MR imaging in type C hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology. 2006;43:698–706. doi: 10.1002/hep.21114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e23.Trzepacz PT, Tarter RE, Shah A, Tringali R, Faett DG, Van Thiel DH. SPECT scan and cognitive findings in subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:170–175. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.2.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e24.Bajaj JS, Sanyal AJ, Bell D, Gilles H, Heuman DM. Predictors of the recurrence of hepatic encephalopathy in lactulose-treated patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1012–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e25.van Leeuwen PA, van Berlo CL, Soeters PB. New mode of action for lactulose. Lancet. 1988;1:55–56. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e26.Als-Nielsen B, Gluud LL, Gluud C. Non-absorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy: systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328 doi: 10.1136/bmj.38048.506134.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e27.Conn HO, Leevy CM, Vlahcevic ZR, Rodgers JB, Maddrey WC, Seeff L, et al. Comparison of lactulose and neomycin in the treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy. A double blind controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:573–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e28.Les I, Doval E, Garcia-Martinez R, Planas M, Cardenas G, Gomez P, et al. Effects of branched-chain amino acids supplementation in patients with cirrhosis and a previous episode of hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1081–1088. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e29.Stauch S, Kircheis G, Adler G, Beckh K, Ditschuneit H, Gortelmeyer R, et al. Oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate therapy of chronic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a placebo-controlled double-blind study. J Hepatol. 1998;28:856–864. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e30.Malaguarnera M, Gargante MP, Cristaldi E, Vacante M, Risino C, Cammalleri L, et al. Acetyl-L-carnitine treatment in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3018–3025. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e31.Tuerk MJ, Fazel N. Zinc deficiency. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:136–143. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328321b395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e32.Conn HO, Bircher J. Conn HO, Bircher J, editors. Quantifying the severity of hepatic encephalopathy: syndromes and therapies Hepatic encephalopathy: syndromes and therapies. East Lansing MI: Medi Ed Press. 1993:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- e33.(Internet) www.meduniwien.ac.at/Neurologie/gedamb/diag/diag08.htm. Vienna: Department of Neurology, Medical Faculty of Vienna, (cited 2011 Aug 22); Spezialambulanz für Gedächtnisstörungen am AKH Wien. [Google Scholar]