Consumption of high glycemic index diets increases the appearance of age-related retinal lesions in mice. C57BL/6 mice fed high glycemic index diets can be used as a new mouse model of early AMD.

Abstract

Purpose.

Epidemiologic data indicate that people who consume low glycemic index (GI) diets are at reduced risk for the onset and progression of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The authors sought corroboration of this observation in an animal model.

Methods.

Five- and 16-month-old C57BL/6 mice were fed high or low GI diets until they were 17 and 23.5 months of age, respectively. Retinal lesions were evaluated by transmission electron microscopy, and advanced glycation end products (AGEs) were evaluated by immunohistochemistry.

Results.

Retinal lesions including basal laminar deposits, loss of basal infoldings, and vacuoles in the retinal pigment epithelium were more prevalent in the 23.5- than in the 17-month-old mice. Within each age group, consumption of a high GI diet increased the risk for lesions and the risk for photoreceptor abnormalities and accumulation of AGEs.

Conclusions.

Consuming high GI diets accelerates the appearance of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD in mice, perhaps by increasing the deposition of toxic AGEs in the retina. The data support the hypothesis that consuming lower GI diets, or simulation of their effects with nutraceuticals or drugs, may protect against AMD. The high GI-fed C57BL/6 mouse is a new model of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD and mimic the early stages of disease and may be useful for drug discovery.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in the elderly.1 Available treatments for this devastating disease are limited, targeting only advanced neovascular AMD. Only 10% of AMD cases are the neovascular form.2–10 The remaining 90% of AMD cases (approximately 7 million patients in the United States) are nonneovascular, for which treatment options are limited and disease progression is inexorable.10 The best strategy to alleviate the personal and public financial burden of this disease is to prevent the onset and progression of AMD pathology.9,11–15 It has been estimated that slowing the progression rate to late-stage AMD by 30% would prevent AMD-related blindness by 50%.16

The preventive potential of various nutrients on retinal health has been explored in many observational studies and an interventional trial, the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS).17–21 AREDS found that an antioxidant cocktail of vitamins C and E, β-carotene, zinc, and copper reduced progression from intermediate to late-stage AMD. Unfortunately, it had no effect on preventing early AMD.22 Recent analyses of data from the AREDS, Nutrition and Vision Project sub-study of the Nurses' Health Study, and the Blue Mountains Eye Study revealed that the onset of early AMD (and progression through the stages of AMD) can be delayed through modulation of dietary carbohydrates. Specifically, it was observed that those who consumed diets containing carbohydrates of a high glycemic index (GI) were at increased risk for AMD onset and progression compared with those who consumed diets of low GI. Importantly, this effect was independent of other nutrients that are thought to modulate the risk for AMD (Chiu CJ, et al. IOVS. 2008;49:ARVO E-Abstract 597).22–27

The GI of a food quantifies the rise in blood glucose level after consumption of 50 g carbohydrate from that particular food compared with the rise in glucose levels after consumption of 50 g carbohydrate from a standard food (glucose, white bread).28 Foods with a high GI induce a larger increase in blood glucose levels than foods with a low GI.

Consumption of low GI diets has also been associated with reduced risk for a number of other chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease (Chiu CJ, et al. IOVS. 2007;48:ARVO E-Abstract 2101).25,26,29–36 By controlling spikes in blood sugar, low GI diets also result in lower levels of serum advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), defined as proteins that are nonenzymatically modified by glucose or its metabolites.37,38 Increased levels of AGEs have been observed under conditions of oxidative stress and inflammation and in several chronic diseases, including AMD.37,39–68 However, there is a paucity of published information about relationships between tissue levels of AGEs and dietary GI.69,70

A large number of mouse models of AMD have been developed (see Ref. 71 for review), many of which are transgenic models that exert acute, severe stress on the retina. We used the C57BL/6 nontransgenic mouse, fed a high or low GI diet (Table 1), to determine whether chronic intake of diets of different GIs affects the rates of appearance of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD and to begin to obtain insights into the pathophysiology of these relationships.72 The lesions have been observed in human and mouse models of aging or AMD and have included the accumulation of basal laminar deposits (BLDs), accumulation of BLD-associated membranous debris, loss of basal infoldings, vacuolization of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), loss of melanin (as an indicator of retinal aging), accumulation of outer collagenous layer deposits, accumulation of lipofuscin, thickening of Bruch's membrane, disorganization of photoreceptor outer segments, thinning of outer photoreceptor nuclear and inner nuclear layers, and retinal accumulation of AGEs (Table 2).

Table 1.

Diet Composition

| Ingredient | High GI Diet (g/kg) | Low GI Diet (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 100% amylopectin (Amioca starch) | 534 | 0 |

| 70% amylose/30% amylopectin (Hylon VII starch) | 0 | 534 |

| Casein | 200 | 200 |

| Sucrose | 85 | 85 |

| Soybean oil | 56 | 56 |

| Wheat bran | 50 | 50 |

| DL methionine | 2 | 2 |

| Vitamin mix | 10 | 10 |

| Mineral mix | 35 | 35 |

| Hydroquinone | 8 | 8 |

| Macronutrient Percentage of Total Energy | High GI Diet (%) | Low GI Diet (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate | 65 | 65 |

| Protein | 21 | 21 |

| Fat | 14 | 14 |

Table 2.

Frequency and Severity Grading Scheme for Age-Related Retinal Lesions That Precede AMD

| Characteristic | Grading of Characteristics Evaluated by Frequency, Severity, or Both |

|

|---|---|---|

| Frequency Score | Severity Score | |

| Basal laminar deposits72–80 | Number of deposits (including severity grades 1–3) per micrometer | 0: no basal laminar deposits |

| 1: <1 μm with amorphous material | ||

| 2: <1 μm with fibrillar material OR >1 μm with amorphous material | ||

| 3: >1 μm with fibrillar material | ||

| Basal laminar deposit-associated membranous debris74,78,81,82 | Quantity of debris per micrometer | N/A |

| Cytoplasmic vacuoles83 | Number of vacuoles (including severity grades 1–3) per micrometer | 0: no vacuoles |

| 1: empty vacuoles | ||

| 2: vacuoles contain granular debris | ||

| 3: vacuoles contain membranous debris or undigested photoreceptor outer segments | ||

| Loss of basal infoldings83,84 | Number of occurrences of absent basal infoldings (including severity grades 1–3) per micrometer | 0: no absence of infoldings within 1 linear μm |

| 1: absence of infoldings within 1 linear μm | ||

| 2: periodic absence of infoldings, each within 1 linear μm OR absence of infoldings of 1–3 linear μm | ||

| 3: absence of infoldings of >3 linear μm | ||

| Thickened Bruch's membrane72,76,77,85 | 0: In each image, the average of the thickest and thinnest points of Bruch's membrane is <0.4 μm 1: In each image, the average of the thickest and thinnest points of Bruch's membrane is >0.4 μm | 0: <0.4 μm |

| 1: 0.4–1 μm and organized | ||

| 2: 0.4–1 μm and disorganized (loss of structure, vacuolization) OR > 1 μm and organized | ||

| 3: >1 μm and disorganized | ||

| Melanin77,86,87 | Number of melanosomes per micrometer | N/A |

| Outer collagenous layer deposits83,88 | Number of deposits (including severity grades 1–3) per micrometer | 0: no deposits |

| 1: <0.5 μm at thickest point of deposit | ||

| 2: 0.5–1 μm at thickest point of deposit | ||

| 3: >1 μm at thickest point of deposit | ||

| Lipofuscin75,77,84,89–93 | Number of lipofuscin-like or melanolipofuscin-like granules per micrometer | N/A |

N/A, not applicable.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

This study was carried out and approved under the Jean Mayer United States Department of Agriculture Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols, in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act provisions and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and with all other animal welfare guidelines, such as the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals

Five- and 16-month-old male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Ten 5-month-old mice were fed a high GI diet until 17 months of age (hereafter referred to as the 17-month-old high GI group) (Table 1). Ten other 5-month-old mice were fed a low GI diet (hereafter referred to as the 17-month-old low GI group) until 17 months of age (Table 1). The only difference between the high and low GI diets was the distribution of starch. The high GI diet starch was composed of 100% amylopectin, whereas the low GI diet starch was composed of 30% amylopectin/70% amylose. The diets were isocaloric and of identical macronutrient distribution (65% carbohydrate, 21% protein, 14% fat). Similar but not identical diets have been used previously in research regarding carbohydrate metabolism.94,95 Five more 5-month-old mice served as controls and were fed a high GI diet without hydroquinone (HQ) until 17 months of age. All 17-month-old mice were fed a high or low GI diet for 46 weeks before euthanasia.

We also fed 10 more 16-month-old mice a high GI diet (hereafter referred to as the 23.5-month-old high GI group), and we fed 10 other 16-month-old mice a low GI diet (hereafter referred to as the 23.5-month-old low GI group) until 23.5 months of age. These mice were fed their specific GI diet for 26 weeks before euthanasia. We chose to analyze middle-aged (17 months of age) and older (23.5 months of age) mice to capture AMD-related pathology because it has been shown that in 12-month-old C57BL/6 mice, age-related retinal lesions are limited and the choroid, Bruch's membrane, and RPE are healthy.89,96

In both age groups, the mice were pair-fed to ensure equal consumption between diet groups. All the diets used in this study were formulated by Bio-Serv (Frenchtown, NJ). National Starch (Bridgewater, NJ) generously donated Amioca starch (100% amylopectin) for incorporation into the high GI diet and Hylon VII starch (30% amylopectin/70% amylose) for incorporation into the low GI diet.

All mice were fasted for 6 hours before euthanasia with carbon dioxide and were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Eyes were enucleated for either transmission electron microscopy analysis or light microscopy analysis.

Transmission Electron Microscopy Analysis

After the mice were euthanized, eyes were marked at the superiormost point using a cauterizing pen. To provide orientation for future analyses, eyes were enucleated, and at the cauterization mark either a suture was inserted or a cut was made in the sclera. For electron microscopy, the eyes were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. Eyes were then postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide buffered by 0.1 M sodium cacodylate before dehydration with ethanol and embedding in epoxy resin. Proper orientation of the eyes was first confirmed by light microscopy analysis of thick sections. Ultrathin sections were then cut along the longitudinal axis from the central 2 × 2 mm area of the retina, 1 mm temporal to the optic nerve. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were examined with an electron microscope (CM-10 or CM-120; Philips, Eindhoven, Netherlands). In the 17-month-old cohort, an average of 16 images were evaluated from each of four mice in the high GI, four mice in the low GI, and three mice in the control (non-HQ) group. In the 23.5-month-old cohort, 30 images on average were evaluated from each of the three mice in the high GI and four mice in the low GI group.

Grading Scheme

Age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD were evaluated according to previously published grading schemes97,98 with modifications to include age-related lesions/indicators such as BLD-associated membranous debris, RPE cytoplasmic vacuoles, loss of basal infoldings, melanin, and lipofuscin (Table 2). In each image, Bruch's membrane thickness was determined by averaging the thickness at the thickest and thinnest points in an image. If the average Bruch's membrane thickness was >0.4 μm (the approximate thickness of Bruch's membrane in a young, healthy mouse73), that image was scored as having a thickened Bruch's membrane (score of 1). If the average Bruch's membrane thickness in each image was <0.4 μm, that image was given a score of 0. The frequency score for each mouse was the sum of those images with a score of 1 divided by the total number of images analyzed in that mouse. Mouse frequency scores were then averaged to find the frequency score for the entire diet or age group.

Frequency scores for other lesions were determined by counting the number of each lesion per micrometer in each image. In each mouse, a frequency score for a particular lesion was determined by averaging all the frequency scores for a particular lesion from the individual images from that mouse. Mouse frequency scores were then averaged to determine the frequency score for the entire diet or age group. In addition, some characteristics were graded on the severity of their appearance (score 0–3) (Table 2). Scores of 0 represented those lesions that had an appearance typical of a young mouse, whereas scores of 3 represented those lesions that would typically appear in an old or a diseased mouse, as detailed in Table 2. In each mouse, a severity score for a particular lesion was determined by averaging all the severity scores for that lesion from the individual images from that mouse. Mouse severity scores were then averaged to determine the severity score for the entire diet/age group.

Student's t-test was used to compare the frequencies of BLDs and the loss of basal infoldings. This test was also used to compare frequencies of cytoplasmic vacuoles, melanin, outer collagenous layer deposits, and lipofuscin between diet and age groups after the data were log-transformed. Wilcoxon's Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the frequencies of BLD-associated membranous debris and a thickened Bruch's membrane between diet and age groups. Severity scores for loss of basal infoldings as well as BLDs, cytoplasmic vacuoles, outer collagenous layer deposits, and Bruch's membrane were also compared between diet and age groups using Wilcoxon's Mann-Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and P < 0.1 was considered marginally significant. All statistical analyses were carried out using statistical software (SAS 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Immunohistochemistry

Eyes were isolated and their orientations were preserved as described. After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and removal of the lens, eyecups were embedded in paraffin and sectioned (5-μm thick) from the central area of the retina, 1 mm temporal to the optic nerve along the longitudinal axis. After deparaffinization with xylene and antigen retrieval with citrate buffer, sections were blocked with 5% goat serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc., West Grove, PA) in 1% BSA/TBS for 2 hours at room temperature.99–101 Sections were then incubated with 0.13 mg/mL goat–anti-mouse (AffiniPure Fab Fragment; Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.) to block endogenous mouse antibody. This was followed by incubation with avidin and biotin (Vectastain ABC Kit, standard; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to block endogenous avidin and biotin. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with 16.3 μg/mL α-MG-H1 (generously provided by M. Brownlee). After several washes, the sections were incubated with 1.7 μg/mL biotin–SP-conjugated goat–anti-mouse antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.) for 30 minutes and were washed and incubated with 1:500 dilution of streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratories) for 30 minutes. Antibody deposition was visualized with an alkaline phosphatase substrate kit (BCIP/NBT; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. For visualization of antigen in the retinal pigment epithelial cells, sections were bleached after immunolabeling with 0.05% potassium permanganate (≥99%; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 25 minutes, followed by incubation with 35% peracetic acid (FMC, Philadelphia, PA) for 25 minutes, in accordance with a modification by Bhutto et al.102 Sections were then mounted with mounting medium (VectaMount AQ; Vector Laboratories). Images were captured with a digital microscope camera (DP70; Olympus, Center Valley, PA) and densitometric analysis of images was performed using ImageJ software (developed by Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; available at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html) to determine the extent of MG-H1 staining in each retinal layer.

Sections were also stained with hematoxylin and eosin to assess the outer and inner nuclear layer thickness of mice fed a high (n = 3) or a low (n = 3) GI diet. For each section, the number of rows of inner and outer nuclei was counted from three different regions of the retina: central, superior, and inferior. For each nuclear layer, these three counts were averaged to produce a single row count for each tissue section. The thickness of each nuclear layer for each mouse was determined by averaging the row counts from each tissue section from that mouse. The thickness of each nuclear layer in the entire diet or age group was determined by averaging the row counts from all the mice in that group. Differences between groups were compared using Student's t-test (SAS 9.2; SAS Institute).

Results

Frequency and Severity of Age-Related Retinal Lesions that Precede AMD in 17- and 23.5-Month-Old Mice of the Same Diet Group

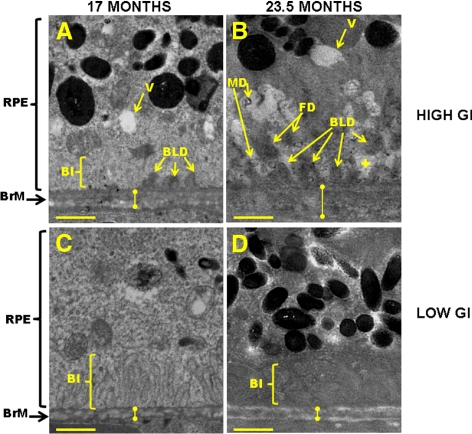

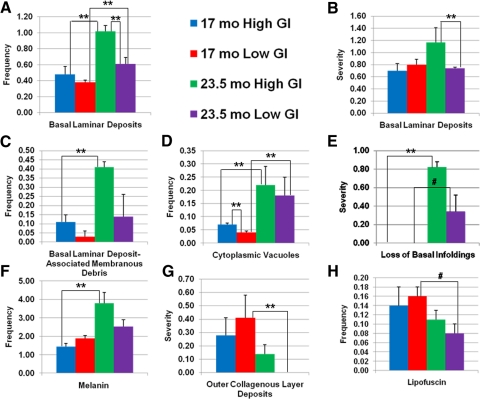

Age-related changes in retinal lesions that are associated with dietary GI have not been previously published. To determine whether animals fed these experimental diets showed advancement of retinal lesions upon aging, we evaluated the frequency and severity of age-related retinal lesions that preceded AMD in 17- and 23.5-month-old mice in each diet group. Deposition on Bruch's membrane of electron-dense BLDs, especially those of a fibrillar or collagenous composition (FD), is associated with aging and is also a precursor of AMD-like lesions.103 BLDs were observed more frequently (P < 0.05) and appeared to be of greater severity (as indicated by FD) in the 23.5-month-old mice than in the 17-month-old mice fed a high GI diet (Figs. 1B vs. 1A, 2A, 2B). BLDs were also more frequent in the 23.5- than in the 17-month-old mice fed a low GI diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A).

Figure 1.

Retinal lesions are more advanced in C57BL/6 mice that were older and that consumed the high GI diet. Electron micrographs of (A) 17-month-old high GI-fed, (B) 23.5-month-old high GI-fed, (C) 17-month-old low GI-fed, and (D) 23.5-month-old low GI-fed mice are shown. Note larger, more advanced BLDs, greater loss of BI, and vacuolization of cytoplasm in B than in A, C, and D. BI, basal infolding; BrM, Bruch's membrane (knobbed lines indicate approximate thickness of Bruch's Membrane); FD, fibrillar deposit; MD, BLD-associated membranous debris; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; V, vacuoles; +, loss of basal infoldings. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Figure 2.

Semiquantitative comparison of retinal aging features between 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed high or low GI diets. Mean values for 17-month-old high GI (blue bars), 17-month-old low GI (red bars), 23.5-month-old high GI (green bars), and 23.5-month-old low GI (purple bars) groups are shown for frequency of BLDs (A), severity of BLDs (B), frequency of BLD-associated membranous debris (C), frequency of cytoplasmic vacuoles (D), severity of loss of basal infoldings (E), frequency of melanin (F), severity of outer collagenous layer deposits (G), and frequency of lipofuscin (H). Error bars represent SEM. **P < 0.05; #P < 0.1. To keep the figure clear, P values for comparison of frequency and severity of lesions between 17-month-old low GI-fed and 23.5-month-old high GI-fed mice are not shown. These statistics are indicated in the text.

BLD-associated membranous debris is a feature associated with retinal disease and aging and is thought to precede the formation of basal linear deposits.74,104 BLD-associated membranous debris was more prevalent in the 23.5-month-old mice than in the 17-month-old mice fed the high GI diet (P < 0.05), and the same relationship was observed for the low-GI fed animals (“MD” in Figs. 1B, 2C). Similarly, small circular RPE cytoplasmic vacuoles were more prevalent in the 23.5-month-old mice than in the 17-month-old mice that consumed the high GI and low GI diets (P < 0.05 in both diet groups) (Fig. 2D).

BLDs often occupy space that was originally populated by basal infoldings. Consistent with the age-related increase in BLDs, the 23.5-month-old mice from both diet groups demonstrated greater severity of loss of basal infoldings than the 17-month-old mice (P < 0.05 and P < 0.1 for high GI and low GI groups, respectively) (plus signs indicate the spaces where basal infoldings, if present, would be found in the retinas of younger mice; Figs. 1B vs. 1A, 2E). Another commonly used metric of retinal aging and disease is Bruch's membrane thickness. Bruch's membrane tended to be thicker in the 23.5-month-old mice compared to the 17-month-old mice fed the high GI diet, but variability within each age group precluded this difference from reaching statistical significance (Figs. 1B vs. 1A, knobbed lines). Combined, these data clearly indicate that with aging the mice fed either diet were at increased risk for many age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD (Figs. 2A–E).

Previous data indicate that the number of melanin granules decreases on aging, but melanin granules had not been measured previously in mice fed these diets.105 We found an unexpected increase in the frequency of melanin pigment granules (P < 0.05) in the 23.5-month-old mice compared with the 17-month-old mice fed the high GI diet (Fig. 2F). The same relationship, albeit muted, was observed in the mice fed the low GI diet. Among the low GI-fed mice, there were also less severe (smaller) outer collagenous layer deposits (P < 0.05) and fewer lipofuscin granules (P < 0.1) in the 23.5-month-old group than in the 17-month-old group (Figs. 2G, 2H).

Frequency and Severity of Age-Related Retinal Lesions That Precede AMD in Age-Matched Mice Fed a High or Low GI Diet

We also compared the effects of dietary GI on the frequency and severity of retinal lesions in age-matched mice. In most cases, consuming the lower GI diet reduced or delayed the appearance of the lesion. This was particularly obvious in the older animals. Thus, the frequency and severity of BLDs was lower in 23.5-month-old mice fed the low GI diet compared with age-matched mice fed the high GI diet (P < 0.05) (Figs. 1D vs. 1B, 2A, 2B). Similar differences were observed for frequency of BLD-associated membranous debris, frequency of cytoplasmic vacuoles, severity of loss of basal infoldings, frequency of melanin, severity of outer collagenous layer deposits, and frequency of lipofuscin deposition in the 23.5-month-old mice (Figs. 2C–H). Some of these diet-related differences were also observed in the younger animals, including fewer BLDs, BLD-associated membranous debris, and cytoplasmic vacuoles (P < 0.05) in the low GI-fed mice (Figs. 1C vs. 1A, 2A, 2C, 2D).

Overall, the differences in frequency and severity of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD appear to be greatest between low-GI fed younger animals and high-GI fed older animals. The most robust differences between 17-month-old low GI-fed mice and 23.5-month-old high GI-fed mice were observed in the frequency of BLDs (P < 0.001), frequency of BLD-associated membranous debris (P < 0.05), frequency of cytoplasmic vacuoles (P = 0.01), severity of loss of basal infoldings (P < 0.05), and frequency of melanin (P = 0.01) (Figs. 2A, 2C–F). For each of these lesions, the frequency or severity was greater in the high GI-fed 23.5-month-old mice, suggesting that older age and higher dietary GI accelerate the retinal changes that precede AMD.

Effects of Dietary GI on AGE Accumulation

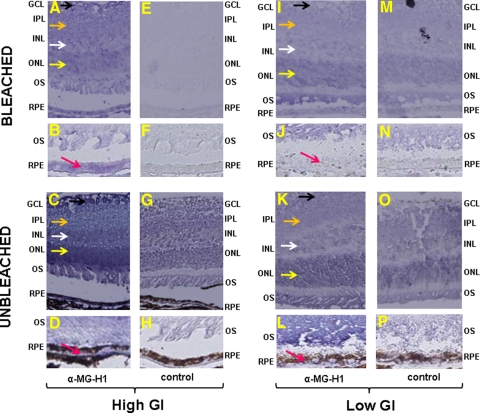

Analyses of tissues from 11-month-old 129SvPas mice fed diets of different GIs for 10 months indicated that mice fed a high GI diet accumulated more MG-H1–modified proteins (hereafter called MG-H1) in their retinas than mice fed a low GI diet.106 MG-H1, one of the most common AGEs, is formed on the reaction of methylglyoxal, a glucose metabolite, with protein.107 If chronic dietary glycemia, and therefore MG-H1 accumulation, were causally related to lesions, we would expect more severe lesions and MG-H1 accumulation in high GI-fed mice. To explore this hypothesis, the retinas were analyzed immunohistochemically. RPE of 17-month-old mice fed the high GI diet had higher levels of MG-H1 than mice that consumed the low GI diet, as indicated in bleached (Figs. 3B vs. 3J, pink arrows) and unbleached (Figs. 3D vs. 3L, pink arrows) sections. Increased deposition of MG-H1 in high GI rather than low GI-fed mouse retinas was also seen in layers of the inner retina, including the outer (yellow arrows) and inner (white arrows) nuclear layers, inner plexiform layer (orange arrows), and ganglion cell layer (black arrows) (Figs. 3A vs. 3I and 3C vs. 3K). The observed AGE accumulation in retinal layers anterior to the RPE suggested that the high GI diet increased glycative stress throughout the retina and prompted us to examine the effects of aging and dietary GI on retinal lesions interior to the RPE.

Figure 3.

MG-H1–modified protein accumulates in the retinas of mice fed a high GI diet. Retinas from 17-month-old mice fed high (A–H) or low (I–P) GI diets were incubated with control serum (E–H, M–P) or α-MG-H1 (A–D, I–L). Deposition of MG-H1–modified protein (blue stain) was evaluated in unbleached (C, D, G, H, K, L, O, P) and bleached (A, B, E, F, I, J, M, N) sections, showing increased deposition in the outer nuclear (yellow arrows), inner nuclear (white arrows), inner plexiform (orange arrows), ganglion cell (black arrows), and RPE (pink arrows) layers of the retinas from high GI-fed mice, corroborating findings on previous Western blot analysis. Images in B, D, F, H, J, L, N, and P were taken at a higher magnification to highlight changes in MG-H1 deposition in the RPE. Compared with controls, there was greater MG-H1 staining in the high GI-fed mice compared with the low GI-fed mice by 53% in the RPE, 21% in the ONL, 24% in the INL, 21% in the IPL, and 25% in the GCL. GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OS, outer segments; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium.

Damage to Photoreceptors and Inner Nuclei in 17- and 23.5-Month-Old Mice Fed High or Low GI Diets

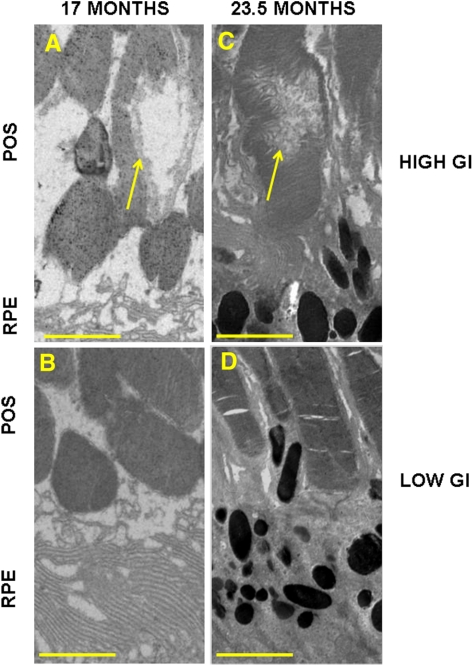

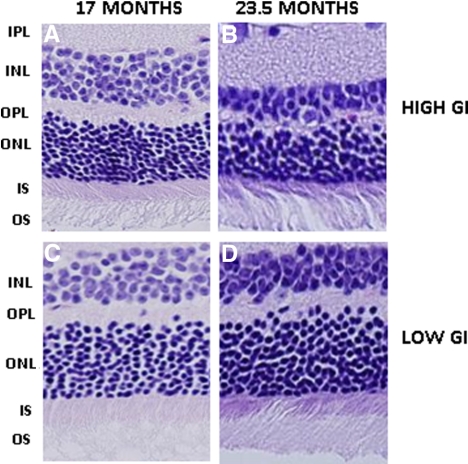

In 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed high or low GI diets, we examined the impact of aging and dietary GI on the integrity of photoreceptors that overlie the RPE. The prevalence of photoreceptor damage was low in all groups. However, more frequent focal photoreceptor outer segment vacuolization and disorganization were observed in high rather than low GI-fed mice (Figs. 4A vs. 4B, 4C vs. 4D; yellow arrows). We did not observe age-related differences.

Figure 4.

Localized damage to photoreceptor outer segments in 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed a high GI diet. Electron micrographs of individual photoreceptor outer segments in mice from the 17-month-old high GI group (A), 17-month-old low GI group (B), 23.5-month-old high GI group (C), and 23.5-month-old low GI group (D). (yellow arrows) Disorganization/vacuolization of outer segments. POS, photoreceptor outer segments; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium. Scale bar, 2 μm.

In addition to outer segment damage, we analyzed the effects of age and GI on the number of rows of photoreceptor outer nuclei because thinning of this layer has been observed in models of AMD.108 Aging was associated with a decrease in the thickness of photoreceptor outer nuclear layers in both diet groups (Table 3; P < 0.01 and P = 0.06 for low and high GI-fed mice, respectively). Although suggestive, the difference in outer nuclear layer thickness between diet groups did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outer Nuclear Layer Thickness in 17- and 23.5-Month-Old Mice Fed a High or a Low GI Diet

| Diet | Rows of Outer Nuclei ± SEM |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 17 mo | 23.5 mo | |

| High GI | 10.4 ± 0.8 | 8.5 ± 0.4* |

| Low GI | 13.1 ± 1.3 | 8.5 ± 0.3† |

Difference in mean thickness of outer nuclear layers between 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed high GI diets (P = 0.06).

Difference in mean thickness of outer nuclear layers between 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed low GI diets (P < 0.01).

Analysis of the inner nuclear layer revealed that older age was associated with thinning of this layer in animals of the same diet group (P < 0.01 for both diet groups) (Figs. 5A vs. 5B and 5C vs. 5D; Table 4). There was also a greater preservation of inner nuclear layers in the 23.5-month-old animals that consumed the low GI diet than in age-matched mice that consumed the high GI diet (P = 0.07) (Fig. 5D vs. 5B; Table 4). In comparison, at 17 months of age, the GI of the diet had less effect on the number of rows of inner nuclei (Figs. 5A vs. 5C; Table 4). These data suggest that the stresses associated with thinning of the inner nuclear layer are prominent later in life and are related to dietary glycemia.

Figure 5.

Retinal nuclei in 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed a high or low GI diet. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections from 17-month-old high GI-fed (A), 23.5-month-old high GI-fed (B), 17-month-old low GI-fed (C), and 23.5-month-old low GI-fed (D) mice are shown. INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS, inner segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; OS, outer segments.

Table 4.

Inner Nuclear Layer Thickness in 17- and 23.5-Month-Old Mice Fed a High or Low GI Diet

| Diet | Rows of Inner Nuclei ± SEM |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 17 mo | 23.5 mo | |

| High GI | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.0* |

| Low GI | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.2*† |

Difference in mean thickness of inner nuclear layers between 17- and 23.5-month-old mice fed diets of the same GI (P < 0.01).

Difference in mean thickness of inner nuclear layers between 23.5-month-old mice fed diets of different GI (P = 0.07).

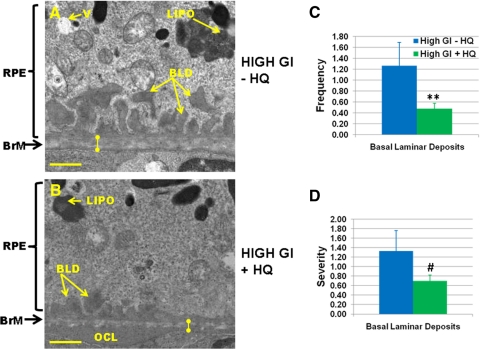

Mice Fed a High GI Diet Show Lesions in the Absence of HQ

Cigarette smoke is known to cause oxidative and other stresses that result in the accelerated formation of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD.72 We adapted a version of this stress by exposing or not exposing animals to HQ, an oxidant in cigarette smoke, with the objective of determining whether consuming lower GI diets delays the formation of these lesions. To evaluate the stress due to dietary HQ compared with that of a high GI diet alone, we compared retinal integrity between 17-month-old mice fed a high GI diet with HQ and those fed a high GI diet without HQ. Surprisingly, the singular insult of consuming the high GI diet resulted in indistinguishable or higher levels of some retinal lesions than were observed when HQ was included in the diet. The latter include higher frequency (P < 0.05) and severity (P < 0.1) of BLDs (Figs. 6A vs. 6B, C, D). The frequency of BLD-associated membranous debris, severity of loss of basal infoldings, Bruch's membrane thickness, frequency of lipofuscin, frequency of cytoplasmic vacuoles, and frequency and severity of outer collagenous layer deposits were not different between 17-month-old mice fed a high GI diet with HQ and age-matched mice fed a high GI diet without HQ (data not shown). Just as the inclusion of HQ in the diet did not exacerbate retinal lesions, the inclusion of HQ did not significantly increase metabolic stress, as indicated by body weight, fasting glucose, glucose tolerance, insulin tolerance, and glycated hemoglobin levels (Supplementary Methods and Fig. S1, http://www.iovs.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1167/iovs.11-8545/-/DCSupplemental).

Figure 6.

Comparable levels of retinal lesions observed in 17-month-old high GI-fed C57BL/6 mice in the absence or presence of HQ. Electron micrographs of retinas from mice fed high GI diets in the absence (A) or presence (B) of HQ. BLD, basal laminar deposit; BrM, Bruch's membrane (knobbed lines indicate thickness of Bruch's membrane); LIPO, lipofuscin-like granule; OCL, outer collagenous layer deposit; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; V, vacuole; +, loss of basal infoldings. Scale bar, 1 μm. Mean values for high GI-fed mice in the absence (blue bars) and presence (green bars) of HQ are shown for frequency of basal laminar deposits (C) and severity of basal laminar deposits (D). Error bars represent SEM. **P < 0.05; #P < 0.1.

Discussion

In this work, we established a relationship between age, frequency or extent of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD, and dietary GI in a murine model. The model faithfully recapitulates human epidemiologic data showing that aging is associated with more advanced lesions and that consuming low GI foods is associated with lower risk for onset and progress of early AMD. We also corroborated previous mechanistic findings by demonstrating tissue accumulation of AGEs in mice fed a higher GI diet and relating that to AGE accumulation in regions of age- and diet-associated retinal pathology.

The absence of a macula limits the capacity of the rodent retina to completely model human AMD; thus, researchers using mouse models72,75,104,108,109 rely on evaluations of retinal lesions that precede and accompany the human disease103,110–112 to determine associations between various treatments and risk for early stages of AMD. We found that on aging, mice fed either a high or a low GI diet showed increased retinal lesions such as accumulation of BLDs and cytoplasmic vacuoles, loss of basal infoldings, and loss of outer and inner nuclear layers, confirming previous reports of the age-associated nature of these lesions (Figs. 1, 2).103,110–113 Importantly, we noted that in general, there were more robust age-related differences in lesion frequency and severity in high GI-fed mice than in low GI-fed mice, indicating that consumption of a low GI diet attenuates and may delay lesions.

The only difference in the diet between the high and low GI groups is the ratio of amylopectin/amylose. Only the lower GI diet contains amylose. The physiological changes associated with consumption of these carbohydrates may explain the differences in the frequency and severity of lesions between diet groups of age-matched mice.114–117 Amylopectin is digested at a faster rate than amylose, resulting in an increased flux of glucose and methylglyoxal into the retina.118 Glycative stress in the retina is demonstrated by increased levels of MG-H1 in the RPE and photoreceptors (Fig. 3). It has been shown that glycative stress from increased glucose catabolism increases the risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease in humans.119,120 Our data suggest that this stress may impact the retina as well, creating an environment predisposed to the accumulation of lesions, as shown in Figures 1, 2, 4, and 5. A plausible link between dietary GI, retinal stress, and retinal aging may be found in deposition of AGEs, the known cytotoxicity of AGEs, and the recently discovered impairment of protein editing caused by glycative stress in the retinas of mice consuming high GI diets.106

The retinal lesions that were accelerated in the high GI-fed mice have also been observed in diabetic rodents, suggesting that it may be possible to use these data to gain insight into nutritional amelioration of diabetic retinopathy, even though these mice are not diabetic. These lesions include vacuolization of the RPE, disorganization of photoreceptor outer segments, decreased thickness of the inner nuclear layer, and accumulation of AGEs in the inner retina.121–126 AGEs directly contribute to the vascular compromises of diabetic retinopathy by increasing levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).127–134 Thus, it seems that consuming lower GI diets should reduce AGEs and the associated risk for the progression of diabetic retinopathy and of AMD.

Implementation of the high GI diet, with or without HQ, allowed us to evaluate the requirement for HQ to accelerate retinal aging and the etiology of age-related retinal lesions that precede AMD. Higher levels of lesions were not observed in animals that consumed a high GI diet with, rather than without, HQ, suggesting that HQ is not necessary to elicit these lesions in animals within the context of a high GI diet. A corollary is that consumption of a high GI diet alone (in the absence of HQ) can be used as a model for retinal aging.

This study shows that age is associated with increasing lesions in the murine retina and that a high GI diet augments this retinal pathology. Overall, the differences in AMD-like lesions appear to be greatest between low GI-fed younger animals and high GI-fed older animals. These data show that the model is responsive to environmental influences such as nutrition and will also be useful for studies of mechanisms of disease initiation. Additionally, the C57BL/6 mouse fed a high GI diet provides a new excellent platform on which to study the effects of modulators (drugs, nutraceuticals) on aging and risk for early AMD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by United States Department of Agriculture Grant 1950-510000-060-01A; Johnson & Johnson Focused Giving; American Health Assistance Foundation; National Institutes of Health Grants 13250, 21212, NEI P30 EY12576 (UCD), EY14004, and EY019904; Thome Foundation Award; and Robert Bond Welch Professorship.

Disclosure: K.A. Weikel, None; P. FitzGerald, None; F. Shang, None; M.A. Caceres, None; Q. Bian, None; J.T. Handa, None; A.W. Stitt, None; A. Taylor, None

References

- 1. Gehrs KM, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hageman GS. Age-related macular degeneration—emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Ann Med. 2006;38:450–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown DM, Michels M, Kaiser PK, Heier JS, Sy JP, Ianchulev T. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin photodynamic therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: two-year results of the ANCHOR study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, Feinsod M, Guyer DR. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friberg TR, Tolentino M, Weber P, Patel S, Campbell S, Goldbaum M. Pegaptanib sodium as maintenance therapy in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: the LEVEL study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1611–1617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forte R, Cennamo G, Finelli M, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone, bevacizumab and pegaptanib for occult choroidal neovascularization. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:e305–e310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tufail A, Patel PJ, Egan C, et al. Bevacizumab for neovascular age related macular degeneration (ABC Trial): multicentre randomised double masked study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biarnes M, Mones J, Alonso J, Arias L. Update on geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. Optom Vis Sci. 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frick KD, Gower EW, Kempen JH, Wolff JL. Economic impact of visual impairment and blindness in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:544–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klein R, Chou CF, Klein BE, Zhang X, Meuer SM, Saaddine JB. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the US population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ivers RQ, Norton R, Cumming RG, Butler M, Campbell AJ. Visual impairment and risk of hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:633–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desrosiers J, Wanet-Defalque MC, Temisjian K, et al. Participation in daily activities and social roles of older adults with visual impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:1227–1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dargent-Molina P, Favier F, Grandjean H, et al. Fall-related factors and risk of hip fracture: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet. 1996;348:145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, Kaplan RM, Brown SI. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wood J, Lacherez P, Black A, Cole M, Boon M, Kerr G. Risk of falls, injurious falls, and other injuries resulting from visual impairment among older adults with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5088–5092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Complications of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Prevention Trial (CAPT): rationale, design and methodology. Clin Trials 2004;1:91–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chiu CJ, Taylor A. Nutritional antioxidants and age-related cataract and maculopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:229–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ma L, Lin XM. Effects of lutein and zeaxanthin on aspects of eye health. J Sci Food Agric. 2010;90:2–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coleman H, Chew E. Nutritional supplementation in age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:220–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weikel KA, Taylor A. Nutritional modulation of age-related macular degeneration. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, eds. Duane's Ophthalmology. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS): design implications. AREDS report no. 1. Control Clin Trials 1999;20:573–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chew EY, Lindblad AS, Clemons T. Summary results and recommendations from the age-related eye disease study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1678–1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiu CJ, Milton RC, Klein R, Gensler G, Taylor A. Dietary carbohydrate and the progression of age-related macular degeneration: a prospective study from the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1210–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chiu CJ, Milton RC, Gensler G, Taylor A. Association between dietary glycemic index and age-related macular degeneration in nondiabetic participants in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chiu CJ, Klein R, Milton RC, Gensler G, Taylor A. Does eating particular diets alter risk of age-related macular degeneration in users of the Age-Related Eye Disease Study supplements? Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;1241–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chiu CJ, Hubbard LD, Armstrong J, et al. Dietary glycemic index and carbohydrate in relation to early age-related macular degeneration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:880–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaushik S, Wang JJ, Flood V, et al. Dietary glycemic index and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:362–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ferland A, Brassard P, Lemieux S, et al. Impact of high-fat/low-carbohydrate, high-, low-glycaemic index or low-caloric meals on glucose regulation during aerobic exercise in type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26:589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, McKeown-Eyssen G, et al. Effect of a low-glycemic index or a high-cereal fiber diet on type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2742–2753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKeown NM, Meigs JB, Liu S, et al. Dietary carbohydrates and cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Framingham offspring cohort. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28:150–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu S, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, et al. Whole-grain consumption and risk of coronary heart disease: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Riegersperger M, Sunder-Plassmann G. How to prevent progression to end stage renal disease. J Ren Care. 2007;33:105–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gopinath B, Harris DC, Flood VM, Burlutsky G, Brand-Miller J, Mitchell P. Carbohydrate nutrition is associated with the 5-year incidence of chronic kidney disease. J Nutr. 2011;141:433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wolever TM, Jenkins DJ, Vuksan V, Jenkins AL, Wong GS, Josse RG. Beneficial effect of low-glycemic index diet in overweight NIDDM subjects. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:562–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sakurai M, Nakamura K, Miura K, et al. Dietary glycemic index and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged Japanese men. Metabolism. 2012;61:47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Singh R, Barden A, Mori T, Beilin L. Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia. 2001;44:129–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fu MX, Wells-Knecht KJ, Blackledge JA, Lyons TJ, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Glycation, glycoxidation, and cross-linking of collagen by glucose: kinetics, mechanisms, and inhibition of late stages of the Maillard reaction. Diabetes. 1994;43:676–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramasamy R, Vannucci SJ, Yan SS, Herold K, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. Advanced glycation end products and RAGE: a common thread in aging, diabetes, neurodegeneration, and inflammation. Glycobiology. 2005;15:16R–28R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Yan SF, Stern DM. The multiligand receptor RAGE as a progression factor amplifying immune and inflammatory responses. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:949–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schmidt AM, Yan SD, Brett J, Mora R, Nowygrod R, Stern D. Regulation of human mononuclear phagocyte migration by cell surface-binding proteins for advanced glycation end products. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2155–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schmidt AM, Hori O, Chen JX, et al. Advanced glycation endproducts interacting with their endothelial receptor induce expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in cultured human endothelial cells and in mice: a potential mechanism for the accelerated vasculopathy of diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1395–1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Miyata T, Hori O, Zhang J, et al. The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) is a central mediator of the interaction of AGE-beta2microglobulin with human mononuclear phagocytes via an oxidant-sensitive pathway: implications for the pathogenesis of dialysis-related amyloidosis. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1088–1094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Owen WF, Jr, Hou FF, Stuart RO, et al. Beta 2-microglobulin modified with advanced glycation end products modulates collagen synthesis by human fibroblasts. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1365–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sakaguchi T, Yan SF, Yan SD, et al. Central role of RAGE-dependent neointimal expansion in arterial restenosis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:959–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Che W, Asahi M, Takahashi M, et al. Selective induction of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor by methylglyoxal and 3-deoxyglucosone in rat aortic smooth muscle cells: the involvement of reactive oxygen species formation and a possible implication for atherogenesis in diabetes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18453–18459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Makita Z, Yanagisawa K, Kuwajima S, Bucala R, Vlassara H, Koike T. The role of advanced glycosylation end-products in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(suppl 5):31–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bierhaus A, Hofmann MA, Ziegler R, Nawroth PP. AGEs and their interaction with AGE-receptors in vascular disease and diabetes mellitus, I: the AGE concept. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:586–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schleicher ED, Wagner E, Nerlich AG. Increased accumulation of the glycoxidation product N(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine in human tissues in diabetes and aging. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:457–468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sasaki N, Fukatsu R, Tsuzuki K, et al. Advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1149–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brownlee M. Glycation products and the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Diabetes Care. 1992;15:1835–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sugiyama S, Miyata T, Ueda Y, et al. Plasma levels of pentosidine in diabetic patients: an advanced glycation end product. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1681–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kilhovd BK, Giardino I, Torjesen PA, et al. Increased serum levels of the specific AGE-compound methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2003;52:163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kilhovd BK, Juutilainen A, Lehto S, et al. Increased serum levels of methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone-AGE are associated with increased cardiovascular disease mortality in nondiabetic women. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:590–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fosmark DS, Berg JP, Jensen AB, et al. Increased retinopathy occurrence in type 1 diabetes patients with increased serum levels of the advanced glycation endproduct hydroimidazolone. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:498–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Han Y, Randell E, Vasdev S, et al. Plasma advanced glycation endproduct, methylglyoxal-derived hydroimidazolone is elevated in young, complication-free patients with type 1 diabetes. Clin Biochem. 2009;42:562–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Araki N, Ueno N, Chakrabarti B, Morino Y, Horiuchi S. Immunochemical evidence for the presence of advanced glycation end products in human lens proteins and its positive correlation with aging. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10211–10214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Snow LM, Fugere NA, Thompson LV. Advanced glycation end-product accumulation and associated protein modification in type II skeletal muscle with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1204–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Semba RD, Fink JC, Sun K, Windham BG, Ferrucci L. Serum carboxymethyl-lysine, a dominant advanced glycation end product, is associated with chronic kidney disease: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Ren Nutr. 2010;20:74–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Sun K, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Plasma carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in older community-dwelling adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1874–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Howes K, Liu Y, Dunaief J, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3713–3720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Torreggiani M, Liu H, Wu J, et al. Advanced glycation end product receptor-1 transgenic mice are resistant to inflammation, oxidative stress, and post-injury intimal hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:1722–1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hofmann SM, Dong HJ, Li Z, et al. Improved insulin sensitivity is associated with restricted intake of dietary glycoxidation products in the db/db mouse. Diabetes. 2002;51:2082–2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Cai W, He JC, Zhu L, et al. Oral glycotoxins determine the effects of calorie restriction on oxidant stress, age-related diseases, and lifespan. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:327–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vlassara H, Cai W, Goodman S, et al. Protection against loss of innate defenses in adulthood by low advanced glycation end products (AGE) intake: role of the antiinflammatory AGE receptor-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4483–4491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ma W, Lee SE, Guo J, et al. RAGE ligand upregulation of VEGF secretion in ARPE-19 cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1355–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Neumann A, Schinzel R, Palm D, Riederer P, Munch G. High molecular weight hyaluronic acid inhibits advanced glycation endproduct-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine expression. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sato T, Wu X, Shimogaito N, Takino J, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M. Effects of high-AGE beverage on RAGE and VEGF expressions in the liver and kidneys. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48:6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chiarelli F, de Martino M, Mezzetti A, et al. Advanced glycation end products in children and adolescents with diabetes: relation to glycemic control and early microvascular complications. J Pediatr. 1999;134:486–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kostolanska J, Jakus V, Barak L. HbA1c and serum levels of advanced glycation and oxidation protein products in poorly and well controlled children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22:433–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rakoczy EP, Yu MJ, Nusinowitz S, Chang B, Heckenlively JR. Mouse models of age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:741–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Suner IJ, Catanuto P, Hernandez EP, Marin-Castano ME, Cousins SW. Cigarette smoke-related oxidants and the development of sub-RPE deposits in an experimental animal model of dry AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:729–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mishima H, Hasebe H. Some observations in the fine structure of age changes of the mouse retinal pigment epithelium. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1978;209:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sarks S, Cherepanoff S, Killingsworth M, Sarks J. Relationship of basal laminar deposit and membranous debris to the clinical presentation of early age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:968–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Saint-Geniez M, Kurihara T, Sekiyama E, Maldonado AE, D'Amore PA. An essential role for RPE-derived soluble VEGF in the maintenance of the choriocapillaris. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18751–18756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Provost AC, Vede L, Bigot K, et al. Morphologic and electroretinographic phenotype of SR-BI knockout mice after a long-term atherogenic diet. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3931–3942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bonilha VL. Age and disease-related structural changes in the retinal pigment epithelium. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2:413–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Cherepanoff S, McMenamin P, Gillies MC, Kettle E, Sarks SH. Bruch's membrane and choroidal macrophages in early and advanced age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:918–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Spraul CW, Grossniklaus HE. Characteristics of Drusen and Bruch's membrane in postmortem eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mishima H, Kondo K. Ultrastructure of age changes in the basal infoldings of aged mouse retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 1981;33:75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Curcio CA, Millican CL. Basal linear deposit and large drusen are specific for early age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Curcio CA, Presley JB, Millican CL, Medeiros NE. Basal deposits and drusen in eyes with age-related maculopathy: evidence for solid lipid particles. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:761–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fujihara M, Bartels E, Nielsen LB, Handa JT. A human apoB100 transgenic mouse expresses human apoB100 in the RPE and develops features of early AMD. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:1115–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Katz ML, Robison WG., Jr Age-related changes in the retinal pigment epithelium of pigmented rats. Exp Eye Res. 1984;38:137–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Augustin AJ, Kirchhof J. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:641–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sundelin SP, Nilsson SE, Brunk UT. Lipofuscin-formation in cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells is related to their melanin content. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Rozanowski B, Cuenco J, Davies S, et al. The phototoxicity of aged human retinal melanosomes. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:650–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. van der Schaft TL, de Bruijn WC, Mooy CM, Ketelaars DA, de Jong PT. Is basal laminar deposit unique for age-related macular degeneration? Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:420–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tuo J, Bojanowski CM, Zhou M, et al. Murine ccl2/cx3cr1 deficiency results in retinal lesions mimicking human age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3827–3836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sparrow JR. Bisretinoids of RPE lipofuscin: trigger for complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;703:63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Luhmann UF, Robbie S, Munro PM, et al. The drusenlike phenotype in aging Ccl2-knockout mice is caused by an accelerated accumulation of swollen autofluorescent subretinal macrophages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5934–5943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Xu H, Chen M, Manivannan A, Lois N, Forrester JV. Age-dependent accumulation of lipofuscin in perivascular and subretinal microglia in experimental mice. Aging Cell. 2008;7:58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sparrow JR, Boulton M. RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal pathobiology. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Isken F, Weickert MO, Tschop MH, et al. Metabolic effects of diets differing in glycaemic index depend on age and endogenous glucose-dependent insulinotrophic polypeptide in mice. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2159–2168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Isken F, Klaus S, Petzke KJ, Loddenkemper C, Pfeiffer AF, Weickert MO. Impairment of fat oxidation under high vs low glycemic index diet occurs prior to the development of an obese phenotype. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E297–E295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zhao Z, Chen Y, Wang J, et al. Age-related retinopathy in NRF2-deficient mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Marin-Castano ME, Striker GE, Alcazar O, Catanuto P, Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Cousins SW. Repetitive nonlethal oxidant injury to retinal pigment epithelium decreased extracellular matrix turnover in vitro and induced sub-RPE deposits in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4098–4112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ida H, Ishibashi K, Reiser K, Hjelmeland LM, Handa JT. Ultrastructural aging of the RPE-Bruch's membrane-choriocapillaris complex in the D-galactose-treated mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2348–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Takai H, Kato A, Ishiguro T, et al. Optimization of tissue processing for immunohistochemistry for the detection of human glypican-3. Acta Histochem. 2010;112:240–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Ha SK, Choi C, Chae C. Development of an optimized protocol for the detection of classical swine fever virus in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by seminested reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and comparison with in situ hybridization. Res Vet Sci. 2004;77:163–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Evke E, Minbay FZ, Temel SG, Kahveci Z. Immunohistochemical detection of p53 protein in basal cell skin cancer after microwave-assisted antigen retrieval. J Mol Histol. 2009;40:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bhutto IA, Kim SY, McLeod DS, et al. Localization of collagen XVIII and the endostatin portion of collagen XVIII in aged human control eyes and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1544–1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sarks SH, Arnold JJ, Killingsworth MC, Sarks JP. Early drusen formation in the normal and aging eye and their relation to age related maculopathy: a clinicopathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:358–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Marmorstein LY, McLaughlin PJ, Peachey NS, Sasaki T, Marmorstein AD. Formation and progression of sub-retinal pigment epithelium deposits in Efemp1 mutation knock-in mice: a model for the early pathogenic course of macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2423–2432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Weiter JJ, Delori FC, Wing GL, Fitch KA. Retinal pigment epithelial lipofuscin and melanin and choroidal melanin in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:145–152 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Uchiki T, Weikel KA, Jiao W, et al. Glycation-altered proteolysis as a pathobiologic mechanism that links dietary glycemic index, aging, and age-related disease (in non diabetics). Aging Cell. 2012;11:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Rabbani N, Thornalley PJ. Methylglyoxal, glyoxalase 1 and the dicarbonyl proteome. Amino Acids. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Justilien V, Pang JJ, Renganathan K, et al. SOD2 knockdown mouse model of early AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4407–4420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Fujihara M, Nagai N, Sussan TE, Biswal S, Handa JT. Chronic cigarette smoke causes oxidative damage and apoptosis to retinal pigmented epithelial cells in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Tso MO. Pathogenetic factors of aging macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Lewis H, Straatsma BR, Foos RY, Lightfoot DO. Reticular degeneration of the pigment epithelium. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:1485–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Sarks SH. Ageing and degeneration in the macular region: a clinicopathologic study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976;60:324–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Picard E, Ranchon-Cole I, Jonet L, et al. Light-induced retinal degeneration correlates with changes in iron metabolism gene expression, ferritin level, and aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1261–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Ader M, Bergman RN. Insulin sensitivity in the intact organism. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;1:879–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Anderson GH, Cho CE, Akhavan T, Mollard RC, Luhovyy BL, Finocchiaro ET. Relation between estimates of cornstarch digestibility by the Englyst in vitro method and glycemic response, subjective appetite, and short-term food intake in young men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;91:932–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. So PW, Yu WS, Kuo YT, et al. Impact of resistant starch on body fat patterning and central appetite regulation. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Robertson MD, Bickerton AS, Dennis AL, Vidal H, Frayn KN. Insulin-sensitizing effects of dietary resistant starch and effects on skeletal muscle and adipose tissue metabolism. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Brouwers O, Niessen PM, Haenen G, et al. Hyperglycaemia-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in rat mesenteric arteries is mediated by intracellular methylglyoxal levels in a pathway dependent on oxidative stress. Diabetologia. 2010;53:989–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M. Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the STOP-NIDDM randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2072–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M. Acarbose treatment and the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: the STOP-NIDDM trial. JAMA. 2003;290:486–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Omri S, Behar-Cohen F, de Kozak Y, et al. Microglia/macrophages migrate through retinal epithelium barrier by a transcellular route in diabetic retinopathy role of PKCzeta in the Goto Kakizaki rat model. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:942–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Tso MO, Cunha-Vaz JG, Shih CY, Jones CW. Clinicopathologic study of blood-retinal barrier in experimental diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:2032–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Arnal E, Miranda M, Johnsen-Soriano S, et al. Beneficial effect of docosahexanoic acid and lutein on retinal structural, metabolic, and functional abnormalities in diabetic rats. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:928–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Sasaki M, Ozawa Y, Kurihara T, et al. Neurodegenerative influence of oxidative stress in the retina of a murine model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53:971–979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Tang L, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, et al. Dietary wolfberry ameliorates retinal structure abnormalities in db/db mice at the early stage of diabetes. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2011;236:1051–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Sohn EJ, Kim YS, Kim CS, Lee YM, Kim JS. KIOM-79 prevents apoptotic cell death and AGEs accumulation in retinas of diabetic db/db mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;121:171–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Lu M, Kuroki M, Amano S, et al. Advanced glycation end products increase retinal vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1219–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Stitt AW, Bhaduri T, McMullen CB, Gardiner TA, Archer DB. Advanced glycation end products induce blood-retinal barrier dysfunction in normoglycemic rats. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;3:380–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Mamputu JC, Renier G. Advanced glycation end products increase, through a protein kinase C-dependent pathway, vascular endothelial growth factor expression in retinal endothelial cells: inhibitory effect of gliclazide. J Diabetes Complications. 2002;16:284–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Murata T, Nakagawa K, Khalil A, Ishibashi T, Inomata H, Sueishi K. The relation between expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier in diabetic rat retinas. Lab Invest. 1996;74:819–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Brownlee M, Cerami A, Vlassara H. Advanced glycosylation end products in tissue and the biochemical basis of diabetic complications. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1315–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Vlassara H, Bucala R. Recent progress in advanced glycation and diabetic vascular disease: role of advanced glycation end product receptors. Diabetes. 1996;45(suppl 3):S65–S66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T, et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits advanced glycation end product-induced retinal vascular hyperpermeability by blocking reactive oxygen species-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20213–20220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Okamoto T, Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, et al. Angiogenesis induced by advanced glycation end products and its prevention by cerivastatin. FASEB J. 2002;16:1928–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.