These findings clearly demonstrate that substratum nanotopography inhibits TGFβ-induced corneal myofibroblast differentiation and suggests that structural features of this scale help to stabilize the keratocyte and fibroblast phenotypes in vivo.

Abstract

Purpose.

The transition of corneal fibroblasts to the myofibroblast phenotype is known to be important in wound healing. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of topographic cues on TGFβ-induced myofibroblast transformation of corneal cells.

Methods.

Rabbit corneal fibroblasts were cultured on nanopatterned surfaces having topographic features of varying sizes. Cells were cultured in media containing TGFβ at concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 ng/mL. RNA and protein were collected from cells cultured on topographically patterned and planar substrates and analyzed for the myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and Smad7 expression by quantitative real time PCR. Western blot and immunocytochemistry analysis for αSMA were also performed.

Results.

Cells grown on patterned surfaces demonstrated significantly reduced levels of αSMA (P < 0.002) compared with planar surfaces when exposed to TGFβ; the greatest reduction was seen on the 1400 nm surface. Smad7 mRNA expression was significantly greater on all patterned surfaces exposed to TGFβ (P < 0.002), whereas cells grown on planar surfaces showed equal or reduced levels of Smad7. Western blot analysis and αSMA immunocytochemical staining demonstrated reduced transition to the myofibroblast phenotype on the 1400 nm surface when compared with cells on a planar surface.

Conclusions.

These data demonstrate that nanoscale topographic features modulate TGFβ-induced myofibroblast differentiation and αSMA expression, possibly through upregulation of Smad7. It is therefore proposed that in the wound environment, native nanotopographic cues assist in stabilizing the keratocyte/fibroblast phenotype while pathologic microenvironmental alterations may be permissive for increased myofibroblast differentiation and the development of fibrosis and corneal haze.

Corneal stromal wounding initiates a cascade of events which results in the activation and differentiation of the relatively quiescent stromal keratocyte to the more proliferative and metabolically active fibroblast and myofibroblast phenotypes.1–4 This transformation is critical in normal wound healing but can also be associated with corneal scar formation and the development of haze,5 a condition in which increased numbers of myofibroblasts at the surgical wound have been observed and corneal opacity is increased, thus impairing vision.6–8 The presence of myofibroblasts at the wound site leads to increased light-scattering, decreased expression of the corneal crystallin ALDH1A1, and the production of a disorganized extracellular matrix, all which contribute to corneal haze.9 Understanding the transition from keratocyte to myofibroblast is critical to the development of therapeutic strategies to reduce corneal scarring and haze.

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) initiates the transition of corneal keratocytes to the repair myofibroblast phenotype.10 Myofibroblasts are defined by their unique expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA) fibers.10 Myofibroblast transition is antagonized by bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and Smad7,2,11–13 which is involved in a negative feedback loop with the Smad-specific ubiquitin ligase Smurf to inhibit TGFβ activity.14

In addition to these known biochemical mediators, corneal stromal keratocytes in vivo are exposed to a multitude of additional environmental stimuli, including the biophysical attributes of the surrounding microenvironment. The native corneal stroma is a rich topographically patterned environment comprising sheet-like transparent fibrillar parallel bundles of collagen, with a sparse population of keratocytes located between the lamellae.2,15 Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of biophysical cues and their impact on other corneal cell types. Several studies have been undertaken to characterize the role(s) of these biophysical cues in mediating cellular behavior.10,16–18 Specifically, Pot et al. 19 demonstrated that nanoscale topography modulates the fundamental behaviors of cultured rabbit corneal keratocytes, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts.

Primary rabbit corneal keratocytes grown in culture can be reliably transformed to the myofibroblast phenotype in growth medium containing added TGFβ.20 Preliminary data from our laboratory suggests that myofibroblasts cultured on nanopatterned surfaces express decreased levels of αSMA (Pot SA, et al. IOVS 2007;48:ARVO E-Abstract 1962). We hypothesized that the native topographically rich environment of the corneal stroma stabilizes the fibroblast phenotype in the presence of TGFβ, while alterations in this environment may increase the transition to the myofibroblast phenotype. The goal of this study was to assess the effect of substratum topography on TGFβ-induced transformation of corneal fibroblast cells to the myofibroblast phenotype through evaluation of mRNA expression, Western blot analysis, and immunohistochemical analysis.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Primary keratocyte cultures were obtained from freshly enucleated rabbit eyes (PelFreez, Rogers, AR) after removal of the cornea and overnight digestion with collagenase and hyaluronidase. Eyes were examined before dissection; all samples were processed within 36 hours of tissue harvest. Tissue culture plates were coated for 30 minutes with 97% collagen I and 3% collagen III (PureCol; Advanced Biomatrix, Fremont, CA) diluted in an equal volume of 12 mM HCl (Acros Oganics, Geel, Belgium) in filter-sterilized H2O. The dishes were then rinsed twice with serum-free medium (Dulbecco's minimum essential medium [DMEM]) containing 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1% vitamin solution (RPMI 1640), 0.055 mg/mL L-ascorbic acid (both from Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B (Invitrogen) and left wet until use. Cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, or Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) supplemented with antibiotics as previously described.20 Cells were incubated for 3 days to assure transition to the fibroblast phenotype.

Fabrication of Micro and Nanoscale Surfaces

Patterned silicon surfaces were constructed at the Center for Nanotechnology (University of Washington-Madison) using x-ray lithography, reactive ion etching, and low pressure chemical vapor deposition silicon oxide coating as previously described.21 Each substrate contains an area with an anisotropic feature size, comprising grooves and ridges of 400 nm, 1400 nm, or 4000 nm pitch (pitch = groove + ridge width), with a groove depth of 300 nm. These silicon surfaces were used as templates for the production of patterned polyurethane cell culture surfaces using soft lithography and composite stamping replication techniques as previously described.22 An electron micrograph of a representative topographic substrate can be seen in our previous work.19 Identically created planar surfaces served as control substrates.

Surfaces were coated with 97% collagen I and 3% collagen III (PureCol; Advanced Biomatrix) for 1 minute as described above directly before use in any of the experiments.

Gene Assays

Fibroblast cultures were plated at a density of 1 × 106 onto 97% collagen I and 3% collagen III (PureCol; Advanced Biomatrix)-coated surfaces of planar or 400 nm, 1400 nm, and 4000 nm pitch sizes. Serum-containing media was removed 24 hours later; two plates of each topographic size were treated by addition of 2 mL of serum-containing medium with 0, 0.1, 1, or 10 ng/mL of TGFβ (Sigma).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Seventy-two hours after TGFβ induction, RNA was extracted using a kit (RNeasy; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed with 75 ng RNA per sample using a one-step kit (TaqMan; Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and commercially available primers for αSMA and Smad7 in total volumes of 10 μL per reaction (Applied Biosystems). The reverse transcription reaction was performed for 20 minutes at 50°C followed by PCR enzyme activation for 10 minutes at 95°C and 40 cycles of 60°C for 1 minute followed by 95°C for 15 seconds. 18S ribosomal RNA served as a reference. At least three reactions were run for each sample, and the experimental setup was performed in triplicate. Gene expression was normalized relative to the expression of mRNA from planar surfaces under the influence of 10 ng/mL TGFβ using the ΔΔCt method as described previously.23 The mRNA from the planar surface at 10 ng/mL of TGFβ was given an arbitrary value of 1.0.

Protein Analysis

After induction for 72 hours in either 0 or 10 ng/mL TGFβ-containing medium, cells were lysed with reagent (M-PER; Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent; Pierce, Rockford, IL) containing protease inhibitors, and the lysate was collected into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes. Removal of insoluble cellular debris was performed by centrifugation at maximum speed (14,000 rpm) in a table top microcentrifuge for 5 minutes; supernatants were collected into fresh tubes. Equivalent volumes of protein samples were loaded onto a gel (NuPAGE Bis-Tris Pre-Cast gel; Invitrogen) after mixing with loading buffer and denaturation by boiling. Gel electrophoresis was performed at 140 V for 1 hour followed by transfer to nitrocellulose at 35 V for 45 minutes. Ponceau S staining was used to confirm successful protein transfer and for protein normalization.

Western Blot Analysis

The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked for 1 hour at room temperature (Milk Diluent Blocking Concentrate; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD), diluted 1:10 in ultrapure water before incubating with mouse anti-αSMA antibody (Sigma) at 1:20,000 dilution in above blocking solution for 2 hours. The blot was washed 5 times in phosphate-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T) for 5 minutes before incubating with conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody (IRDye 800CW; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) at 1:20,000 dilution for 1 hour in the dark. After washing 5 times in PBS-T for 5 minutes, the blot was scanned with an infrared imaging system (Odyssey; LI-COR). Relative intensities of infrared signals were normalized with Ponceau S staining intensities. Densitometric analyses were performed with software (ImageQuant TL; GE Health Care Life Sciences, Waukesha, WI). Western blot analysis was performed on samples from three independent experiments.

Immunocytochemistry

Both planar and 1400 nm pitch collagen-coated surfaces were seeded with cells in growth medium as previously described; 0 or 10 ng/mL TGFβ in growth medium was added 24 hours postseeding. After 72 hours in experimental medium, cells were washed 3 times in 1x PBS, then fixed with 4% formaldehyde in 1x PBS for 10 minutes. After three additional 1x PBS washes, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes. Blocking was performed with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 1x PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. The samples were then incubated with 1:200 mouse anti-αSMA antibody (Sigma) in 1% BSA at room temperature for 60 minutes. Cells were washed 3 times with 1x PBS before incubation with Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody at 1:400 in 1% BSA at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes (Invitrogen). Cell nuclei were stained for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen). Finally, the cells were left in 1x PBS until immunofluorescent imaging with an epifluorescent microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss Imaging Solutions GmbH, Munich, Germany). For analysis of αSMA protein expression, 20 random images of each plate surface were taken using the 20 × air objective for both DAPI and Alexa 488 fluorescence. Cells displaying Alexa 488 signal were counted as positive for αSMA, while DAPI-stained nuclei were counted for total cells per image. Each surface and experimental medium combination was performed in triplicate for a total of 12 plates analyzed, and the experiment was repeated three times in total.

Statistical Analysis

Within one experiment, all data sets were compared with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When variability between the data set means was determined to be significant, a Bonferroni multiple comparison test was used to compare selected data sets. For direct comparison between groups, the Tukey test was used. The level for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 for all comparisons. Graphing (GraphPad Prism 2003; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and plotting (Sigma Plot; Systat Software, San Jose, CA) software were used for statistical analyses.

Results

Topographic Cues Decrease αSMA Gene Expression

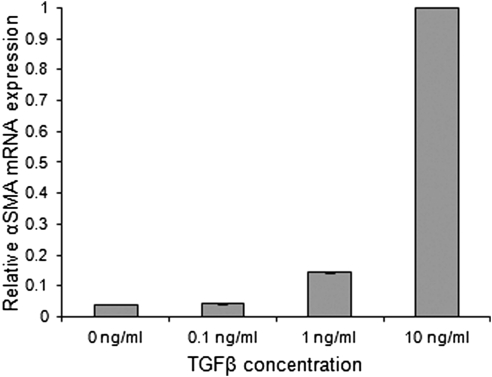

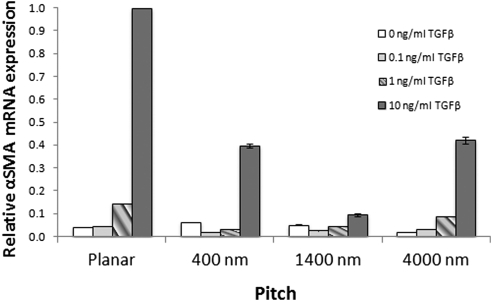

αSMA gene expression displayed a clear dose-response to TGFβ (Fig. 1). Cells grown on planar surfaces expressed negligible levels of αSMA at 0 and 0.1 ng/mL TGFβ. Rabbit corneal stromal cells grown under serum-positive conditions comprise a small percentage of myofibroblasts.20 This would be consistent with the αSMA expression observed in fibroblasts not exposed to TGFβ. A threefold increase in αSMA expression was observed at 1 ng/mL and a 23-fold increase at 10 ng/mL. The provision of topographic cues significantly decreased αSMA gene expression when compared with planar surfaces. All cells cultured on topographically patterned surfaces demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in relative αSMA mRNA expression (P < 0.005; Fig. 2). The greatest decrease in expression was seen on the 1400 nm pitch size, which showed a 90% decrease in expression when cells were exposed to 10 ng/mL TGFβ. The decreased αSMA mRNA expression was demonstrable in three different experiments.

Figure 1.

TGFβ exposure correlates with a measurable increase in αSMA gene expression in fibroblasts. Minimal αSMA expression is seen at the 0 and 0.1 ng/mL concentrations of TGFβ. A threefold increase was observed at 1 ng/mL and a 23-fold increase at 10 ng/mL.

Figure 2.

Exposure to all topographically patterned surfaces decreases αSMA expression in rabbit corneal stromal cells. Expression is presented as the amount of αSMA relative to the planar surface at 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Cells grown on all topographically patterned surfaces demonstrated significantly reduced levels of αSMA compared with the planar surface when exposed to at least 1 ng/mL of TGFβ. Cells on the 1400 nm pitch surface expressed the lowest levels of αSMA, expressing 3.3-fold less than those on planar surfaces at 1 ng/mL TGFβ and 10.7-fold less αSMA at 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Error bars indicate SEM. **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.002.

Topographic Cues Inhibit the Transition to the Corneal Myofibroblast Phenotype

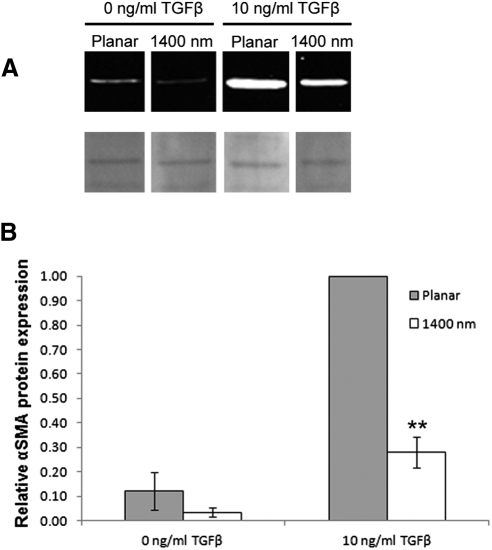

Western blot analysis was performed on samples collected from corneal cells cultured on either planar or 1400 nm surfaces in the presence or absence of added TGFβ. Cells on planar substrates cultured in 10 ng/mL TGFβ showed the highest level of αSMA protein expression, while expression in cells cultured on 1400 nm pitch in the same medium was considerably lower (Fig. 3A). Normalization of αSMA signal intensities with Ponceau S staining indicated that cells on 1400 nm pitch decreased αSMA protein expression by more than threefold compared with cells on planar surfaces (P < 0.01; Fig. 3B). Similar results were obtained with β-actin normalization (data not shown).

Figure 3.

αSMA protein is reduced in corneal stromal cells cultured on 1400 nm pitch compared with planar surfaces. (A) Western blot analysis of lysates from cells cultured on surfaces and media as shown (top row); Ponceau S band used for semiquantitative normalization shown below blots. Images are from the same blot reordered for clarity. (B) Graph indicating normalization of αSMA protein signal intensities; signal is significantly reduced on 1400 nm compared with adjacent planar control. Error bars indicate SEM. **P < 0.01.

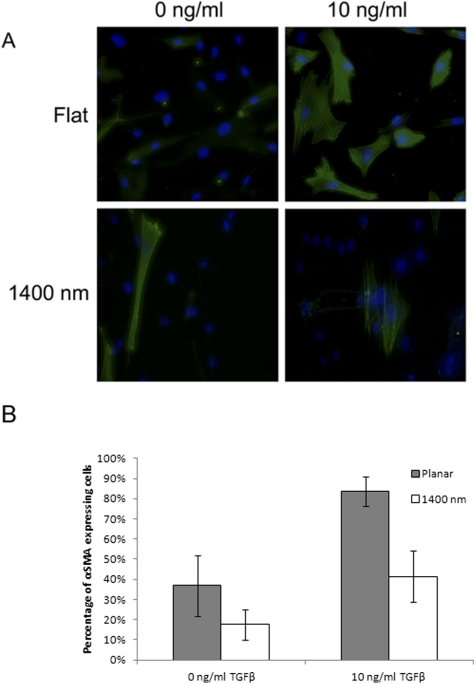

To determine whether the observed decrease in αSMA protein from Western blot analysis results in fewer individual cells forming αSMA fibers, as opposed to a uniform decrease in SMA expression across all cells cultured on topography, immunocytochemical staining for αSMA was performed. Decreased numbers of myofibroblasts were observed on the 1400 nm pitch compared with planar surfaces when cells were exposed to 10 ng/mL TGFβ (Fig. 4). Percent transformation was significantly reduced in cells cultured on the 1400 nm pitch, decreasing from 83.8% on planar surfaces to 41.5% on the 1400 nm pitch (P < 0.05; Fig. 4). Taken together, these results indicate that topographic features can attenuate TGFβ-mediated differentiation in corneal stromal cells.

Figure 4.

Exposure to topographically patterned surfaces decreases transformation of rabbit corneal fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. (A) Representative images of stromal cells cultured on indicated substrates and indicated amounts of exogenous TGFβ added to growth medium. Green signal: αSMA; blue: DAPI. (B) Graph depicting quantification of αSMA-positive cells. Cells grown on the 1400 nm pitch had fewer than 50% the number of transformed cells than those grown on planar surfaces when exposed to 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05.

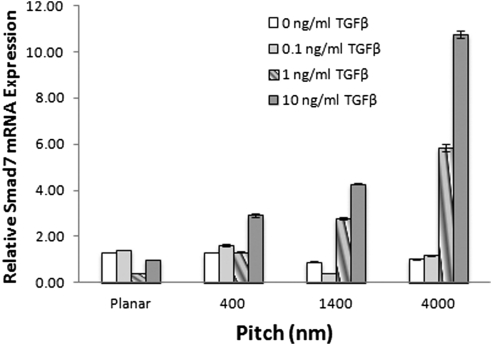

Topographic Cues Increase Smad7 Gene Expression

Topographic features were uniquely associated with increased expression of Smad7. Cells grown on planar surfaces at all concentrations of TGFβ demonstrated low levels of Smad7. However, Smad7 expression was significantly increased on all patterned surfaces with TGFβ concentrations of 1 ng/mL or greater (P < 0.002). A threefold increase in expression on 400 nm and a fourfold increase on 1400 nm were observed at a TGFβ concentration of 10 ng/mL (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Exposure to all pitch sizes of topographically patterned surfaces increases Smad7 expression in rabbit corneal fibroblasts. Expression is presented as the amount of Smad7 relative to the planar surface at 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Cells grown on all topographically patterned surfaces demonstrated significantly increased levels of Smad7 (**P < 0.002) compared with the planar surface when exposed to at least 1 ng/mL of TGFβ. Cells on 4000 nm pitch expressed the highest levels of Smad7, expressing a 5.8-fold increase in Smad7 expression at 1 ng/mL TGFβ and 10.7-fold increase in Smad7 at 10 ng/mL TGFβ. Representative graph of the experiment completed in triplicate. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

Topographic Cues Impact Cell Behavior

Biophysical cuing has emerged as an important factor in the modulation of multiple cellular behaviors. Many cell types in multicellular organisms intimately associate with a specialization of the extracellular matrix, the basement membrane. To better understand the native microenvironments cells experience in vivo, basement membranes from different species and tissues have been characterized with both electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy, revealing an interconnecting network of submicron and nanoscale fibers, undulations, and pores.24–27 Cells residing on the surface of basement membranes directly contact thousands of these features. Although most corneal stromal cells are not adjacent to a basement membrane, they are interspersed between lamellae comprising fibrillar bundles of uniformly sized collagen fibers with defined spatial architecture in the nanoscale range and thus experience contact with nanoscale topographic features.1

In recent years, several studies have shown that multiple cell types respond to biophysical cues. A wide variety of cell behaviors, including proliferation, adhesion, spreading, migration, extracellular matrix protein secretion, and differentiation, can be affected by changes in the topographic features of the cellular microenvironment. For example, in the cornea, fundamental behaviors of epithelial and stromal cells, including proliferation, adhesion, and migration, are modulated by substratum topography.19,21,22,28 The proliferative and differentiation capacities of human embryonic stem cells have been shown to be influenced by culture on engineered topographic surfaces.29–32 Mesenchymal cells have been shown to differentiate into mineral-producing osteoblasts when cultured on a nanoscale scaffold in the absence of osteogenic medium,33 a media typically necessary for differentiation induction in this cell type. Additionally, the ability of human osteoblasts to spread and adhere was found to be attenuated on nanoscale pits in vitro.34 Vascular endothelial cells cultured on anisotropically ordered nanoscale ridges and grooves preferentially elongated and migrated parallel to the long axis of the substrate.35 Over 3000 genes were found to be more than twofold up- or downregulated in vascular endothelial cells by the presentation of topographic cues.36 Collectively, these findings demonstrate the importance of biophysical cues in modulating behaviors of multiple cell types.

Substratum Topography Stabilizes the Corneal Fibroblast Phenotype In Vitro

In the present study, we examined if micro- and nanoscale substratum topography had an effect on TGFβ-mediated corneal fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Our results demonstrate that the provision of these topographic cues inhibits the transition of rabbit corneal stromal cells from the fibroblast to the myofibroblast phenotype, as determined by the expression of αSMA. The decreased expression of αSMA mRNA and protein, particularly on the 1400 nm pitch, suggests that structural features of this scale help to stabilize the keratocyte and fibroblast phenotypes, even in the presence of TGFβ. As Western blot analysis is semiquantitative and cannot discern whether all cells decrease αSMA expression overall or if individual cells do not express αSMA, we performed immunocytochemical staining. This analysis of stromal cells cultured on topography indicates that it is the fundamental transition from the fibroblast to myofibroblast phenotype that is inhibited on nanoscale topography. These findings suggest that in vivo, the native topographic features of the surrounding microenvironment in the stroma play a role in the maintenance of the less differentiated corneal stromal cell phenotypes. In a corneal wounding event, this architecture is disrupted, which may aid in TGFβ-mediated transition to the myofibroblast phenotype. Myofibroblasts that persist at the corneal wound site after closure increase light-scattering, show decreased expression of corneal crystallins, and produce a disordered extracellular matrix, leading to loss of transparency and scarring.5–8,37 Understanding the factors that can mediate keratocyte phenotype stabilization may enable the development of therapies to reduce corneal scarring and haze.

A previous study by Netto et al.6 indicated that larger-scale topographic irregularities caused by corneal surgical intervention contribute to myofibroblast generation and haze formation in vivo. These larger-scale disruptions undoubtedly result in micro- and nanoscale alterations as well. We have demonstrated that nanoscale features help to stabilize the fibroblast phenotype. It is possible that macro-, micro-, and nanoscale changes may all contribute to altered myofibroblast behavior; this question warrants further investigation.

It is important to note that myofibroblasts found in corneal wounds differentiate from both native keratocytes and from bone marrow-derived cells.38 Currently, it is unclear what percentage of myofibroblasts is of bone marrow cell origin during in vivo corneal wounding. In our study, all myofibroblasts were derived from corneal fibroblasts, and it is unknown whether myofibroblasts of differing origins will respond in a similar manner to micro- and nanoscale topographic cues. A recent study on stem cells derived from rat bone marrow suggests that their differentiation potential is modulated by the provision of nanotopographic cues39; however, to date, no studies have been carried out on the differentiation capacity of bone-derived myofibroblasts in the cornea in response to such cues. Future studies on this process are warranted.

The Role of Smad7 in Substratum Topographic Inhibition of Myofibroblast Transition

Smad7 appears to play an inhibitory role in topographic substratum-induced effects on differentiation. The decrease in αSMA expression is concurrent with an increase in Smad7 mRNA expression. Smad7 is a well-established feedback inhibitor for TGFβ-driven processes,2,11,40–42 and disruption of Smad7 has been shown to increase fibrosis, likely through the loss of this feedback mechanism.11,40–43 We hypothesize that the effect of nanotopography on fibroblast behavior is mediated through upregulation of Smad7. The greatest increase in Smad7 expression was seen on the 4000 nm surface size while the greatest decrease in αSMA mRNA expression occurred on the 1400 nm pitch size. This may reflect a difference between mRNA and protein expression, such as a delay between peak message expression and peak protein expression. Smad7 exerts its inhibition of TGFβ-driven transformation to the myofibroblast phenotype via multiple mechanisms, including TGFβ receptor degradation. Smad7 recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligases Smurf1 and Smurf2, which bind and degrade the TGFβ receptor TβR1,44 which also results in Smad7 degradation. One possible explanation for these results is that Smad7 mRNA expression is lower on the 1400 nm pitch size due to increased receptor degradation compared with the 4000 nm pitch. Future studies on topographic feature size, Smad7 gene and protein expression, and TβR1 may clarify the interplay between them in the fibroblast to myofibroblast transition process.

We acknowledge that two-dimensional culture systems do not directly mimic the more complex 3-D environment of the native cornea. Complex spatial signals within a 3-D matrix can change protein expression. Matrices are currently being developed and studied that attempt to address the problem of the third dimension.45–49 However, the use of our anisotropically-patterned two-dimensional surfaces with controlled topographic patterns of defined feature shape, size scale, and surface order allows us to isolate cell responses to very specific topographic stimuli.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the presence of nanoscale to submicron topographic features decreases the TGFβ-driven transition of rabbit corneal stromal fibroblasts to the myofibroblast phenotype. The increased expression of inhibitory Smad7 suggests a mechanism for this transition inhibition, and further studies to elucidate the role of Smad7 and its associated signaling molecules in this process are warranted. We theorize that the topographically rich environment of the native corneal stroma stabilizes the keratocyte phenotype, whereas pathologic alterations in the environment that disrupt normal topographic cuing are permissive for the change to the myofibroblast phenotype. Scenarios where this may come into play include corneal inflammation with enzymatic degradation of the extracellular matrix and corneal refractive surgical procedures. Additional studies on the effects of in vivo corneal microenvironment disruption on stromal cell behavior, particularly the stromal cell differentiation pathway, are required to better understand the gamut of processes leading to scarring and haze.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH 5R01EY012253-07, NIH EY07348-20, NIH EYO16665, NSF MRSEC DMR-9632527, NSF MRSEC CTS-9703207, NIH P30EY12576, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Disclosure: K.E. Myrna, None; R. Mendonsa, None; P. Russell, None; S.A. Pot, None; S.J. Liliensiek, None; J.V. Jester, None; P.F. Nealey, None; D. Brown, None; C.J. Murphy, None

References

- 1. Snyder MC, Bergmanson JP, Doughty MJ. Keratocytes: no more the quiet cells. J Am Optom Assoc. 1998;69:180–187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yan X, Liu Z, Chen Y. Regulation of TGF-beta signaling by Smad7. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2009;41:263–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jester JV, Petroll WM, Barry PA, Cavanagh HD. Expression of alpha-smooth muscle (alpha-SM) actin during corneal stromal wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:809–819 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Netto MV, Mohan RR, Ambrosio R, Jr, Hutcheon AE, Zieske JD, Wilson SE. Wound healing in the cornea: a review of refractive surgery complications and new prospects for therapy. Cornea. 2005;24:509–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saika S, Yamanaka O, Sumioka T, et al. Fibrotic disorders in the eye: targets of gene therapy. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:177–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Netto MV, Mohan RR, Sinha S, Sharma A, Dupps W, Wilson SE. Stromal haze, myofibroblasts, and surface irregularity after PRK. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:788–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moller-Pedersen T. Keratocyte reflectivity and corneal haze. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:553–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moller-Pedersen T, Cavanagh HD, Petroll WM, Jester JV. Stromal wound healing explains refractive instability and haze development after photorefractive keratectomy: a 1-year confocal microscopic study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1235–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jester JV, Budge A, Fisher S, Huang J. Corneal keratocytes: phenotypic and species differences in abundant protein expression and in vitro light-scattering. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2369–2378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jester JV, Ho-Chang J. Modulation of cultured corneal keratocyte phenotype by growth factors/cytokines control in vitro contractility and extracellular matrix contraction. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:581–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeisberg M, Hanai J, Sugimoto H, et al. BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat Med. 2003;9:964–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. You L, Kruse FE. Differential effect of activin A and BMP-7 on myofibroblast differentiation and the role of the Smad signaling pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:72–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Savagner P. Leaving the neighborhood: molecular mechanisms involved during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Bioessays. 2001;23:912–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inoue Y, Imamura T. Regulation of TGF-beta family signaling by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2107–2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ. Cornea. 2nd ed Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dalby MJ, Riehle MO, Sutherland DS, Agheli H, Curtis AS. Use of nanotopography to study mechanotransduction in fibroblasts-methods and perspectives. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seliktar D. Extracellular stimulation in tissue engineering. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:386–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Teixeira AI, McKie GA, Foley JD, Bertics PJ, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. The effect of environmental factors on the response of human corneal epithelial cells to nanoscale substrate topography. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3945–3954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pot SA, Liliensiek SJ, Myrna KE, et al. Nanoscale topography-induced modulation of fundamental cell behaviors of rabbit corneal keratocytes, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1373–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jester JV, Barry-Lane PA, Cavanagh HD, Petroll WM. Induction of alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and myofibroblast transformation in cultured corneal keratocytes. Cornea. 1996;15:505–516 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teixeira AI, Abrams GA, Bertics PJ, Murphy CJ, Nealey PF. Epithelial contact guidance on well-defined micro- and nanostructured substrates. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1881–1892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liliensiek SJ, Campbell S, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. The scale of substratum topographic features modulates proliferation of corneal epithelial cells and corneal fibroblasts. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:185–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bookout AL, Cummins CL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Pesola JM, Kramer MF. High-throughput real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2006;Chapter 15:Unit 15 18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abrams GA, Schaus SS, Goodman SL, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Nanoscale topography of the corneal epithelial basement membrane and Descemet's membrane of the human. Cornea. 2000;19:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abrams GA, Murphy CJ, Wang ZY, Nealey PF, Bjorling DE. Ultrastructural basement membrane topography of the bladder epithelium. Urol Res. 2003;31:341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abrams GA, Goodman SL, Nealey PF, Franco M, Murphy CJ. Nanoscale topography of the basement membrane underlying the corneal epithelium of the rhesus macaque. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;299:39–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abrams GA, Bentley E, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Electron microscopy of the canine corneal basement membranes. Cells Tissues Organs. 2002;170:251–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tocce EJ, Smirnov VK, Kibalov DS, Liliensiek SJ, Murphy CJ, Nealey PF. The ability of corneal epithelial cells to recognize high aspect ratio nanostructures. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4064–4072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levenberg S, Huang NF, Lavik E, Rogers AB, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer R. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on three-dimensional polymer scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12741–12746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith LA, Liu X, Hu J, Ma PX. The influence of three-dimensional nanofibrous scaffolds on the osteogenic differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2516–2522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McFarlin DR, Finn KJ, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Nanoscale through substratum topographic cues modulate human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. J Biomim Biomater Tissue Eng. 2009;2:15–26 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee MR, Kwon KW, Jung H, et al. Direct differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into selective neurons on nanoscale ridge/groove pattern arrays. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4360–4366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Tare R, et al. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nat Mater. 2007;6:997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Biggs MJ, Richards RG, Gadegaard N, Wilkinson CD, Dalby MJ. The effects of nanoscale pits on primary human osteoblast adhesion formation and cellular spreading. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liliensiek SJ, Wood JA, Yong J, Auerbach R, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Modulation of human vascular endothelial cell behaviors by nanotopographic cues. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5418–5426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gasiorowski JZ, Liliensiek SJ, Russell P, Stephan DA, Nealey PF, Murphy CJ. Alterations in gene expression of human vascular endothelial cells associated with nanotopographic cues. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8882–8888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saika S, Yamanaka O, Sumioka T, et al. Transforming growth factor beta signal transduction: a potential target for maintenance/restoration of transparency of the cornea. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36:286–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barbosa FL, Chaurasia SS, Cutler A, et al. Corneal myofibroblast generation from bone marrow-derived cells. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:92–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang G, Zheng L, Zhao H, et al. In vitro assessment of the differentiation potential of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells on genipin-chitosan conjugation scaffold with surface hydroxyapatite nanostructure for bone tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:1341–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saika S. TGFbeta pathobiology in the eye. Lab Invest. 2006;86:106–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Funaki T, Nakao A, Ebihara N, et al. Smad7 suppresses the inhibitory effect of TGF-beta2 on corneal endothelial cell proliferation and accelerates corneal endothelial wound closure in vitro. Cornea. 2003;22:153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sumioka T, Ikeda K, Okada Y, Yamanaka O, Kitano A, Saika S. Inhibitory effect of blocking TGF-beta/Smad signal on injury-induced fibrosis of corneal endothelium. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2272–2281 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang W, Koka V, Lan HY. Transforming growth factor-beta and Smad signalling in kidney diseases. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Itoh S, ten Dijke P. Negative regulation of TGF-beta receptor/Smad signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lawrence BD, Marchant JK, Pindrus MA, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Silk film biomaterials for cornea tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1299–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flanders KC. Smad3 as a mediator of the fibrotic response. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:47–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kobayashi T, Liu X, Kim HJ, et al. TGF-beta1 and serum both stimulate contraction but differentially affect apoptosis in 3D collagen gels. Respir Res. 2005;6:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pedersen JA, Swartz MA. Mechanobiology in the third dimension. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:1469–1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim A, Lakshman N, Karamichos D, Petroll WM. Growth factor regulation of corneal keratocyte differentiation and migration in compressed collagen matrices. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:864–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]