Abstract

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is a rare condition characterized by multiple pneumocysts in the submucosa or subserosa of the bowel. Here, we report a rare case of asymptomatic PI after chemotherapy induction in an 18-yr-old man with B lymphoblastic leukemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities. The patient was treated conservatively and recovered without complications. The possibility of PI should be considered as a complication during or after chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies. Conservative treatment should be considered unless there are complications, including peritonitis, bowel perforation, and severe sepsis.

Keywords: Pneumatosis intestinalis, B lymphoblastic leukemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities, Chemotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is a physical or radiographic finding caused by a large variety of underlying conditions and ranges from benign to fatal [1]. Multiple mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of PI have been proposed, but the pathogenesis is not yet fully understood. Several chemotherapeutic agents are associated with PI, including cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, docetaxel, irinotecan, and cisplatin [2-5]. Abdominal radiography and computed tomography (CT) are the best techniques for diagnosing PI [1]. The spectrum of treatment modalities ranges from emergency surgery to conservative treatment. The choice of therapeutic modality wholly depends on the patient's condition. The course of PI is benign in the absence of severe complications [6]. Here, we report a rare case of asymptomatic PI in an 18-yr-old man after induction of chemotherapy for B lymphoblastic leukemia with recurrent genetic abnormalities.

CASE REPORT

An 18-yr-old man who had been diagnosed with B lymphoblastic leukemia with a t(1;19)(q23;p13); (E2A/PBX1) complex karyotype was admitted for consolidation chemotherapy. He was treated with induction chemotherapy 2 mo prior to admission, and his bone marrow showed complete remission (CR). The induction chemotherapy consisted of prednisolone, daunorubicin, vincristine, asparaginase, and intrathecal methotrexate. On admission, he underwent routine laboratory tests and plain imaging. Chest radiography and upright abdominal radiography revealed gas collection along the wall of the colon and intraperitoneal free air (Fig. 1, 2). The vital signs were normal. On physical examination, the patient presented only with slight abdominal distention. His abdominal walls were soft, and the bowel sounds were unremarkable. He had mild anorexia, which had been present before his diagnosis. He had no history of constipation, diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting. There were no signs of peritonitis. Laboratory results revealed a leukocyte count of 8.0×109/L with 87% neutrophils, a platelet count of 278×109/L, and a hemoglobin level of 9.9 g/dL. Other laboratory findings, including electrolytes, liver function tests, amylase, and CRP, were within normal ranges. No acidosis was shown by atrial blood gas analysis.

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray demonstrating perigastric and pericolic gas accumulation.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal X-ray demonstrating a hyperlucent shadow along the entire colon.

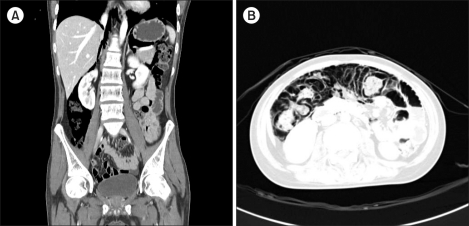

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed and revealed intramural gas along the colon as well as intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal free air (Fig. 3). The diagnosis of PI was made. Since there were no signs of secondary complications, such as peritonitis, conservative treatment was initiated. The patient was treated with high concentrations of oxygen (40% oxygen), broad-spectrum antibiotics (ceftazidime, metronidazole, and teicoplanin), and parenteral alimentation; oral intake was withheld. A blood culture remained negative for microorganisms. No Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter were isolated from the stool. A Clostridium difficile toxin assay was negative. Multiple stool samples showed no occult blood.

Fig. 3.

(A) Abdominal computed tomography (CT) image revealed pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum. (B) Abdominal CT image showed intramural and extramural gas of the ascending and transverse colon. It is seen more easily using a lung window setting.

After 2 wk of therapy, abdominal radiography and CT showed almost complete resolution of PI. The patient progressed well, and abdominal CT taken after 4 wk of therapy showed no evidence of PI. However, a few days later, the patient developed fever, and blasts were seen on his peripheral blood smear. These findings were similar to his condition on the first diagnosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Hyper-CVAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone) chemotherapy was initiated, and a follow-up bone marrow study revealed a second CR. The patient progressed well and received a haploidentical stem cell transplantation from his mother, because he did not have an HLA-matched sibling or unrelated donor.

DISCUSSION

PI is a rare condition characterized by multiple pneumocysts in the submucosa or subserosa of the bowel [7]. Several pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed to underlie PI: (1) increased intraluminal pressure, (2) defective mucosal integrity, and (3) bacterial gas production. All of these can contribute to the formation of intraluminal gas. Mechanical obstruction, blunt trauma, or vomiting can increase intraluminal pressure and cause PI [8]. Enhanced gut permeability to gas can be induced by defects in the mucosa or the gut's immune barrier (intramural lymphoid tissue). Attenuation of these barriers may account for PI in circumstances of normal intraluminal pressure, as seen in patients with PI due to immunosuppressive therapy and cytotoxic therapy. When the mucosal or immune barriers of the GI tract are compromised, bacterial invasion or gas diffusion into the wall becomes more likely. Bacterial production of gas has been suggested by several researchers. This theory is supported by reports that the gas disappears on treatment with antimicrobial drugs. However, the pathogenesis of PI is not fully understood. Based on an autopsy study, the overall incidence of PI in the general population is 0.03% [7]. It has been reported that 15% of PI is idiopathic, and 85% is secondary to various conditions, including intestinal ischemia or infarction, inflammatory bowel diseases, infections, endoscopic procedures, surgeries, alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, and some chemotherapeutic agents. The differential diagnosis for acute abdomen and radiological images of the abdomen are important for diagnosis of PI. Abdominal radiography and CT are the best techniques for diagnosing PI. On both radiographs and CT, PI usually appears as a low-density linear or bubbly pattern of gas in the bowel wall. CT is more sensitive than radiography at detecting PI [9, 10]. CT is also more sensitive for detecting hepatic portal and portomesenteric venous gas [11-13], the presence of which increases the possibility of PI due to life threatening causes [14].

There are limited data concerning treatment of PI. The treatment of PI depends on the patient's presenting symptoms and comorbidity. Clinical deterioration or signs of peritonitis and perforation are accepted surgical indications. However, PI can be asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously in some cases [15]. In mild cases, such as the present case, conservative treatment with antibiotics and nasogastric decompression can be effective. Hence, the presence of PI alone is not an indication for surgical intervention.

The prognosis of PI ranges from benign to fatal and depends on underlying diseases and complications. Many reports have indicated that PI is fatal in cases with intraportal gas, perforation, or severe sepsis. In contrast, cases without complications usually show favorable outcomes. However, the presence of pneumoperitoneum and/or portal venous gas does not necessarily represent an abdominal crisis requiring operative intervention [1]. The imaging findings do not always correlate with outcomes. Therefore, the clinical history, physical examination, and laboratory tests are important for determining the management of PI. In the case of asymptomatic PI, early diagnosis is important. If a patient with asymptomatic PI is treated with a scheduled chemotherapy regimen without perceiving PI, myelosupression by chemotherapy may exacerbate PI and cause life-threatening complications, such as severe sepsis or bowel perforation. Early diagnosis can prevent such events.

In conclusion, PI should be considered as a complication during or after chemotherapy for patients with hematologic malignancies.

References

- 1.St Peter SD, Abbas MA, Kelly KA. The spectrum of pneumatosis intestinalis. Arch Surg. 2003;138:68–75. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashimoto S, Saitoh H, Wada K, et al. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis after chemotherapy for hematological malignancies: report of 4 cases. Intern Med. 1995;34:212–215. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Candelaria M, Bourlon-Cuellar R, Zubieta JL, Noel-Ettiene LM, Sanchez-Sanchez JM. Gastrointestinal pneumatosis after docetaxel chemotherapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:444–445. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih IL, Lu YS, Wang HP, Liu KL. Pneumatosis coli after etoposide chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1623–1625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kung D, Ruan DT, Chan RK, Ericsson ML, Saund MS. Pneumatosis intestinalis and portal venous gas without bowel ischemia in a patient treated with irinotecan and cisplatin. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:217–219. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9846-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee WI, Jang JJ, Hong SI, et al. Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis with intestinal volvulus. J Korean Surg Soc. 2009;76:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heng Y, Schuffler MD, Haggitt RC, Rohrmann CA. Pneumatosis intestinalis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1747–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae SH, Hwang JY, Kim DK, et al. A case of pneumatosis intestinalis in refractory acute precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia-lymphoma. Korean J Med. 2011;80:482–485. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caudill JL, Rose BS. The role of computed tomography in the evaluation of pneumatosis intestinalis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:223–226. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198704000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor R, Jones B, Fishman EK, Siegelman SS. Pneumatosis intestinalis: role of computed tomography in diagnosis and management. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1984;8:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federle MP, Chun G, Jeffrey RB, Rayor R. Computed tomographic findings in bowel infarction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:91–95. doi: 10.2214/ajr.142.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindera ST, Triller J, Vock P, Hoppe H. Detection of hepatic portal venous gas: its clinical impact and outcome. Emerg Radiol. 2006;12:164–170. doi: 10.1007/s10140-006-0467-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher JK. Computed tomography of colonic pneumatosis intestinalis with mesenteric and portal venous air. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1984;8:573–574. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198406000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho LM, Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult: benign to life-threatening causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1604–1613. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day DL, Ramsay NK, Letourneau JG. Pneumatosis intestinalis after bone marrow transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;151:85–87. doi: 10.2214/ajr.151.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]