Abstract

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation remains the only curative therapy for myelofibrosis. Despite advances in transplant, the morbidity and the mortality of the procedure necessitate careful patient selection. In this manuscript, we describe the new prognostic scoring system to help select appropriate patients for transplant and less aggressive therapies. We explore the advances in non-transplant therapy, such as with investigational agents. We review the blossoming literature on results of myeloablative, reduced intensity and alternative donor transplantation. Finally, we make recommendations for which patients are most likely to benefit from transplantation.

Keywords: transplantation, myelofibrosis, cord blood

Definitions of myelofibrosis

Myelofibrosis is now categorized based on the World Health Organization criteria as a myeloproliferative neoplasm. Myelofibrosis can be either primary or secondary, developing in patients with polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia.1 The median age is in the seventh decade and clinical features include anemia, splenomegaly and bone marrow fibrosis. About 70% of patients are positive for the Janus2 kinase (JAK2 kinase) mutation.2 Patients must fulfill all the three major criteria (megakaryocyte proliferation, no evidence of other myeloid neoplasm, and JAK2/V617F or other clonal marker, or no reactive marrow fibrosis) and two minor criteria (leukoerythroblastosis, increased serum lactate dehydrogenase, anemia, palpable splenomegaly) to have primary myelofibrosis.3

Risk stratification

Several prognostic systems have been developed over the last 20 years to help determine which patients might benefit from aggressive transplantation treatment. The older scoring system, such as the Lille or Dupriez, and the Cervantes score, focused primarily on blood counts as the major prognostic factors.4 A newer prognostic system is the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS), which includes age >65, hemoglobin level <10, white blood count >25 × 109/l, circulating blasts ⩾1% and presence of constitutional symptoms.5 The IPSS was further modified to the dynamic IPSS (DIPSS) for use at any time during the course of the disease, and then to the DIPSS Plus, which also incorporates the need for red blood cell transfusions, platelet count <100 × 109/l and unfavorable karyotype (Table 1).6

Table 1. DIPSS Plus.

| Variable | DIPSS (points) | DIPSS Plus (points) |

|---|---|---|

| Age >65 years | 1 | 1 |

| Constitutional symptoms | 1 | 1 |

| Hemoglobin <100 g/l | 2 | 1 |

| White blood count >25 × 109/l | 1 | 1 |

| Circulating blasts >1% | 1 | 1 |

| Platelet count <100 × 109/l | — | 1 |

| Red blood cell transfusion-dependent | — | 1 |

| Unfavorable karyotype | — | 1 |

Abbreviation: DIPSS, Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System.

Prognosis

Newer prognostic models have incorporated the DIPSS Plus model. Low-risk disease is defined as the presence of no adverse factors, and has a median survival of 15 years.6 Intermediate-1 risk is the presence of one risk factor and has a median survival of 7 years. Patients with intermediate-2 disease have two or three risk factors and a median survival of 2.9 years. Finally, high-risk patients have four or more adverse factors with a median survival of only 1.3 years. Thus, these newer prognostic models can aid in selecting the appropriate higher risk patients for transplantation. Recently, an analysis of 884 patients, which included 38% DIPSS Plus patients, reported features associated with a greater than 80% 2-year mortality. These poor prognostic features included monosomal karyotype, inv (3)/i(17q) abnormalities, or any two of the following factors: peripheral blast percentage >9%, white blood count ⩾40 × 109/l or other unfavorable karyotype.7 Thus, these modern predictive scores allow selection of patients who are likely to do poorly with conventional treatment.

Choice of treatment

Although allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) remains the only known curative therapy for myelofibrosis, other treatment options must be considered, especially for patients with lower risk disease. These options include observation, erythroid-stimulating agents, hydroxyurea, prednisone, thalidomide or lenalidomide.8, 9 Response rates, including improvement in blood counts and splenomegaly, vary but are about 20%.10 Low-dose radiation treatments or splenectomy can also be helpful for painful splenomegaly.11 These treatments may be helpful for palliation of symptoms, but the responses are of short duration, usually less than 1 year.

Investigational treatments

Investigational options for the treatment of myelofibrosis have blossomed with the discovery of JAK2 kinase inhibitors. The JAK2 inhibitors tested in clinical trial include INCB018424, TG101348 and CEP-701.12 The majority of patients had improvement in constitutional symptoms, and 44% had improvement in spleen size, with major side effects being thrombocytopenia and a cytokine rebound reaction.12 Other drugs under investigation include pomalidomide and the histone deacetylase inhibitors.13 The impact of these investigational agents on the long-term management of myelofibrosis is uncertain.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation

Myeloablative transplant

Allogeneic transplantation is the only known curative treatment for myelofibrosis. Several studies have shown survival rates of 40–60% after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (Table 2). The first transplants for myelofibrosis used myeloablative conditioning, usually total body radiation or busulfan-based treatment. Guardiola et al.14 reported on 55 patients with a median age of 42 years and showed a 5-year overall survival of 47%. Anemia was a predictive factor for poor survival.

Table 2. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis.

| Author | N | Median age (years) | 1-year TRM, % | 5-year overall survival, % | 5-year progression free-survival, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballen et al.15 | 289 | 47 | 27 (sibling), 43 (unrelated) | 37 (sibling), 30 (unrelated) | 33 (sibling), 27 (unrelated) |

| Patriarca et al.16 | 100 | 49 | 35 | 31 | 28 |

| Robin et al.17 | 147 | 53 | 29 (4 years) | 39 (4 years) | 32 (4 years) |

| Kerbauy et al.22 | 104 | 47 | 27 | 61 (7 years) | — |

| Deeg et al.21 | 56 | 43 | 35 | 58 | — |

Abbreviation: TRM, transplant-related mortality.

The largest study, reported by Ballen et al.15 from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), analyzed 289 patients with primary myelofibrosis. Patients were transplanted between 1989 and 2002 at 118 centers, with a variety of conditioning regimens. Patient and disease characteristics were very heterogeneous, as typical for registry studies. A total of 162 patients received a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling transplant, 101 received a matched unrelated donor (MUD) transplant and 26 received a graft from a non-HLA-matched related donor. The majority of patients received bone marrow as the stem cell source, and 83% received an ablative regimen, likely reflecting the time period of the study. The 100-day transplant-related mortality was 18% for the HLA-matched sibling patients and 33% for the MUD patients. Graft failure rate was 9% for the HLA-matched sibling patients and 20% for the MUD patients. Splenomegaly did not impact the graft failure rate. Graft versus host disease (GVHD) grades II–IV occurred in 43% of the sibling patients and 40% of the MUD patients. The overall survival at 5 years was 37% for the sibling patients and 30% for the MUD recipients. Disease-free survival at 5 years was 33% for recipients of an HLA-identical sibling allograft and 27% for recipients of a MUD transplant. Thus, about one out of three patients can be cured of their disease after allogeneic transplant. Positive predictors for survival in this study included an HLA-identical sibling donor, performance status ⩾90% and no peripheral blood blasts.15 Patients who had a poor Karnofsky score, peripheral blood blasts and an unrelated donor had 15% 3-year probability of survival.

Other reports of allogeneic transplant have confirmed the findings of the CIBMTR study. The Italian group analyzed 100 patients from 26 centers; 48% received a myeloablative conditioning regimen.16 The risk of graft failure was 13%, and the 1-year transplant-related mortality was 35%. The 5-year overall and disease-free survival rates were 31% and 28%, respectively. Positive predictors for survival included an HLA-matched sibling donor, transplantation after 1995 and a short interval between diagnosis and transplantation.

The French group reported similar results. A total of 147 patients with primary or secondary myelofibrosis received an allogeneic stem cell transplant, 31% with a myeloablative regimen.17 Sixty percent of patients received a transplant from an HLA-identical sibling donor. Forty-three percent of patients had acute GVHD, grades II–IV. The 4-year overall survival was 39%, progression-free survival 32% and the non-relapse mortality was 39%. In a multivariate analysis, neither the Lille nor IPSS score predicted survival. Positive predictors for survival included splenectomy, female gender and an HLA-identical sibling donor.

Other studies have confirmed these results. The Seattle group reported on 104 patients with myelofibrosis, either primary or after polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia.18 The survival at 7 years was 61%. Use of a targeted busulfan-based chemotherapy regimen, younger age and a lower comorbidity score predicted for better survival. Investigators, including Mittal et al.19, Ditschokowski et al.20, Deeg et al.21, Kerbauy et al.22 and Daly et al.23 have all reported 3-year probabilities of overall survival of 37–58% in small series.

Reduced-intensity conditioning

Because of the advanced age of many patients with myelofibrosis and hematological malignancies, and the high transplant-related mortality with traditional myeloablative conditioning, the transplant community has pioneered reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC). The RIC regimens use chemotherapy, often fludarabine-based, which is more immunosuppressive than myelosuppressive.24, 25, 26 Early RIC studies for myelofibrosis included the work of Devine et al.27 and Rondelli et al.28. Table 3 outlines the larger studies for myelofibrosis. Kroger et al.29 treated 103 patients with primary myelofibrosis or myelofibrosis post-polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia. Patients received a busulfan- and fludarabine-based conditioning regimen. A total of 98% of the patients engrafted, and acute GVHD grades II–IV occurred in 27% of the patients. The incidence of relapse at 3 years was 22%, and patients with a low Lille score had a lower incidence of relapse, 14% versus 34%, suggesting patients transplanted earlier in the course of disease fared better. The 5-year event-free survival was 51% and as expected, younger patients and those with a matched donor did better. These results are impressive and mimic the survival seen with a myeloablative preparative regimen.

Table 3. Reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis.

| Author | N | Median age (years) | 1-year TRM, % | 5-year overall survival, % | 5-year progression-free survival, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kroger et al.29 | 103 | 53 | 16 | 67 | 51 |

| Merrup et al.30 | 27 | 51 | 10 (RIC), 30 (ablative) | 90 (RIC), 55 (ablative) | — |

| Ballen et al.15 | 60 | 47 (myeloablative and RIC) | 15 | — | 39 |

| Bacigalupo et al.37 | 46 | 51 | 24 | 45 | 43 |

| Alchalby et al.42 | 162 | 57 | 22 | 62 | 46 |

| Stewart et al.32 | 51 | 54 | 32 (RIC), 41 (ablative; 3 years) | 31 (RIC), 44 (ablative) | 24 (RIC), 44 (ablative) |

Abbreviations: RIC, reduced-intensity conditioning; TRM, transplant-related mortality.

The Swedish group compared results from 17 patients undergoing myeloablative with 10 patients undergoing reduced intensity transplant for myelofibrosis.30 Transplant-related mortality was lower in the reduced intensity arm, 10% versus 30%. With a median follow-up of 55 months, 90% of reduced intensity patients and 55% of the myeloablative patients are alive. However, the groups were not randomized. There were no significant predictors of improved survival.

The CIBMTR study, reported by Ballen et al.15 and described above, included 60 patients who received reduced intensity or non-myeloablative regimens. Transplant-related mortality was 15%, less than for the myeloablative patients, and disease-free survival was comparable at 39%. Snyder et al.31 using tacrolimus and sirolimus for GVHD prophylaxis, reported a low incidence (10%) of acute GVHD grades III–IV and 93% survival. Stewart et al.32 treated 27 patients with a myeloablative and 24 patients with a reduced intensity regimen. There was no difference in non-relapse mortality, overall survival or progression-free survival between the myeloablative and reduced intensity groups. With the use of RIC regimens, patients in their 60's and 70's have been transplanted successfully.33 Predictive factors for survival are difficult to ascertain in the large registry studies that combine both myeloablative and RIC recipients. The RIC regimens have been instrumental in expanding transplant eligibility; these regimens reduce the transplant-related mortality compared with high-intensity regimens, but without randomized studies, the exact improvement in survival is difficult to determine.

Alternative donor transplant

Only 30% of patients have a matched sibling donor and it is often difficult for African Americans and other minorities to find MUDs. Alternative stem cell graft sources for these patients include umbilical cord blood, a mismatched unrelated donor, or a mismatched family member (haploidentical) transplant. These graft sources have never been compared in a randomized fashion, and the optimal graft source for patients without a fully matched related donor or MUD is uncertain.34 Umbilical cord blood transplantation is a useful alternative stem cell source for patients without matched donors.35 Because of the delayed engraftment routinely seen after cord blood transplant, transplant physicians may have been reluctant to extend cord blood transplantation to patients with myelofibrosis. The recent report of Takagi et al.36 suggest that successful engraftment can be achieved after reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation for myelofibrosis. Fourteen patients classified as myelofibrosis, including several that had transformed to acute myelogeneous leukemia, underwent cord blood transplant with an RIC regimen. In all, 13 patients engrafted, and the overall survival was 29% at 4 years.

Predictors for survival

Selection of the appropriate patients for transplant and the appropriate timing of transplant have been difficult, given the early risk associated with transplant, even a reduced intensity transplant. Predictive factors studied have included age, graft source, performance status, comorbidity score, splenomegaly, Dupriez score or IPSS score. The CIBMTR study reported by Ballen et al.15 found that an HLA-identical sibling donor, performance status ⩾90% and no peripheral blood blasts predicted for better survival. Recently, Bacigalupo et al.37 have formulated a predictive score for survival. Forty-six patients underwent a reduced intensity transplant for primary myelofibrosis with a thiotepa-based regimen, either thiotepa and cyclophosphamide, or thiotepa, cyclophosphamide and melphalan. In a multivariate analysis, independent factors for poor survival were >20 red blood cell transfusions, spleen size >22 cm and an alternative donor. Two or more risk factors were considered high risk, and these high-risk patients had a 5-year survival of 8%, compared with 77% for the low-risk patients with 0 or 1 risk factor. These results suggest that certain high-risk patients may not benefit from allogeneic stem cell transplant. The predictive score maintained its predictive value even when correcting for patient age, Dupriez, or IPSS score.

Scott et al.38 presented a preliminary analysis of predictive factors for survival after allogeneic transplantation for myelofibrosis. The authors retrospectively studied 169 recipients of allogeneic HCT in Seattle. The International Working Group score, based on age, constitutional symptoms, anemia, leukocytosis and circulating peripheral blasts, was highly predictive for survival after HCT. At 1 year, survival was 40% in the high-risk group and 80% in the low-risk group.

Splenomegaly and splenectomy

The appropriate management of the spleen pre-HCT remains controversial. Ciurea et al.39 showed prolonged neutrophil and platelet recovery in patients with massive splenomegaly, but no effect on survival. Preliminary data from the CIBMTR in a broader population found that splenectomy facilitates engraftment, but had no effect on transplant-related mortality.40 Recently, post-transplant splenectomy has been studied as a way to manage delayed engraftment in patients with splenomegaly and myelofibrosis.41

Markers of minimal residual disease

The role of JAK2 V617F status after transplant is controversial. A study of 162 patients treated with RIC showed a reduced survival in patients with the JAK2 wild type.42 Patients who cleared the JAK2 mutation 6 months after transplant had a lower risk of relapse (5% versus 35%, P=0.03). The reappearance of the JAK2 gene mutation after transplant was associated with the presence of mixed chimerism and relapse; thus, JAK2 mutation serves as a marker of minimal residual disease.43 The JAK2 kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib has recently been approved by the United States Food and Drug Association and is commercially available. The role of the JAK2 kinase inhibitors as part of a transplantation strategy is unclear; these drugs might be helpful for disease reduction pre-HCT or as maintenance therapy post-HCT.

Treatment failure

The options for patients that relapse after HCT are limited. Stewart et al.32 showed a trend toward a higher rate of relapse in patients who received RIC regimens compared retrospectively with patients who received myeloablative conditioning. Donor lymphocyte infusion has been utilized for post-HCT relapse, but it is not clear if there is a strong graft versus myelofibrosis effect.32

Choosing between transplant and non-transplant therapy

Allogeneic transplant remains the only curative therapy for myelofibrosis, but the transplant-related mortality remains high, at 15–30%, and there can be significant morbidity for patients with chronic GVHD. Thus, the selection of patients for transplant is crucial. Some centers will transplant only those patients whose median survival is less than 5 years without transplant, such as those patients with intermediate-2 and high-risk disease.44 Another approach would be to exclude patients with high-risk features of splenomegaly >22 cm, >20 transfusions and alternative donor as defined by Bacigalupo et al.37; these patients have less than a 10% survival after HCT.

For low-risk patients, a more aggressive approach is to monitor these patients and to perform transplant early in the disease if there are any signs of progression, such as anemia, increased lactate dehydrogenase or constitutional symptoms.45

How to manage the transplant question in myelofibrosis

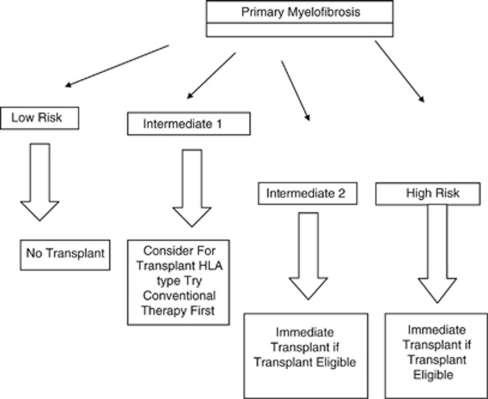

At Massachusetts General Hospital, we perform allogeneic transplants up to age 75. In general, patients over age 60 years or with significant comorbid disease will receive a reduced intensity regimen, usually busulfan and fludarabine. Younger patients receive a myeloablative regimen with busulfan and cyclophosphamide. Patients without a matched sibling donor proceed to unrelated donor search. If an HLA 10/10 allele-matched donor is identified, patients will receive an unrelated transplant. Patients without matched related donor or fully MUD receive double cord blood transplant at our center.35 Patients must have a performance status of 0, 1, 2 and adequate organ function to proceed to transplant. An algorithm for transplantation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection strategy for transplantation in primary myelofibrosis.

As many patients with myelofibrosis enjoy prolonged survival, we select those patients whose survival is likely to be less than 5 years with conventional therapy. Patients with monosomal karyotype have a median survival of 6 months and should be transplanted promptly.46

Patient with low-risk disease by the DIPSS criteria have a median survival of 15 years and should not be considered for transplant, given the morbidity and mortality of allogeneic transplant.10 Patients with intermediate-1 disease have a median survival of 6 years; these patients are considered for transplant and HLA typing performed. However, these patients' symptoms can often be managed by hydroxyurea or low-dose splenic radiation, and it is reasonable to try these measures first before proceeding to transplant. However, most patients with intermediate-1 disease will die of myelofibrosis or its complications, and should be considered as potential transplant candidates.

Patients with intermediate-2 have a median survival of 2.9 years, and patients with high-risk disease have a median survival of 1.3 years. These patients are considered for immediate transplant as soon as a suitable donor is identified. Patients who have transformed to acute leukemia receive induction chemotherapy before transplantation. Patients with massive splenomegaly may undergo low-dose splenic radiation before transplant.

Patients who are likely to have <10% long-term survival after transplant are excluded from transplant. These patients may have the risk factors mentioned, including massively enlarged spleen and a significant transfusion requirement. Patients with poor performance status and significant comorbid conditions may not be transplant candidates.

Conclusion

Treatment for myelofibrosis has evolved with a better understanding of the prognostic factors for survival. Investigational agents such as pomalidomide are currently in clinical trial, and a JAK2 kinase inhibitor is now approved for use in the United States. Allogeneic transplant remains the only known curative therapy for this disease. The advent of RIC has extended the upper age limit of HCT into the 70's. Alternative donor transplantation, including umbilical cord blood transplantation, has provided a larger number of patients, particularly minority patients, with the option for transplant. Over the next 5 years, reduction of transplant-related mortality and optimal patient selection will ensure continued progress in this field.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi AM, Antonioli E, Guglielmelli P, Pardanani A, Tefferi A. Clinical correlates of JAK2V617F presence or allele burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms: a critical reappraisal. Leukemia. 2008;22:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Thiele J, Orazi A, Kvasnicka HM, Barbui T, Hanson CA, et al. Proposals and rationale for revision of the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis: recommendations from an ad hoc international expert panel. Blood. 2007;110:1092–1097. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupriez B, Morel P, Demory JL, Lai JL, Simon M, Plantier I, et al. Prognostic factors in agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: a report on 195 cases with a new scoring system. Blood. 1996;88:1013–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes F, Dupriez B, Pereira A, Passamonti F, Reilly JT, Morra E, et al. New prognostic scoring system for primary myelofibrosis based on a study of the International Working Group for Myelofibrosis Research and Treatment. Blood. 2009;113:2895–2901. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-170449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangat N, Caramazza D, Vaidya R, George G, Begna K, Schwager S, et al. DIPSS-Plus: a refined Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System (DIPSS) for primary myelofibrosis that incorporates prognostic information from karyotype, platelet count, and transfusion status. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:392–397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Jimma T, Gangat N, Vaidya R, Begna KH, Hanson CA, et al. Predictors of greater than 80% 2-year mortality in primary myelofibrosis: a Mayo Clinic study of 884 karyotypically annotated patients. Blood. 2011;118:4595–4598. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-371096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes F, Alvarez-Laran A, Hernandez-Boluda JC, Sureda A, Torrebadell M, Montserrat E. Erythropoietin treatment of the anemia of myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia: results in 20 patients and review of the literature. Brit J Hematol. 2004;127:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Cortes J, Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Thomas D, Lasho TL, et al. Lenalidomide therapy in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2006;108:1158–1164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A. How I treat myelofibrosis. Blood. 2011;117:3494–3504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-315614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Mesa RA, Nogomey DM, Schroeder G, Silverstein MN. Splenectomy in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia: a single-institution experience with 223 patients. Blood. 2000;95:2226–2233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Mesa RA, Pardanani AD, Cortes-Franco J, Thomas DA, et al. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK 1 and JAK 2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1117–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begna KH, Mesa RA, Pardanani A, Hogan WJ, Litzow MR, McClure RF, et al. A phase 2 trial of low-dose pomalidomide in myelofibrosis with anemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:301–304. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardiola P, Anderson JE, Bandini G, Cervantes F, Funde V, Arcese W, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: a European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle, Gruppos Italiano per il Trapianto Del Midollod Osseo, and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Collaborative Study. Blood. 1999;93:2831–2838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballen KK, Shrestha S, Sobocinski KA, Zhang MJ, Bashey A, Bolwell BJ, et al. Outcome of transplantation for myelofibrosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca F, Bacigalupo A, Sperotto A, Isola M, Soldano F, Bruno B, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in myelofibrosis: the 20-year experience of the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto di Midollo Osseo (GITMO) Hematologica. 2008;93:1514–1522. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robin M, Tabrizi R, Mohty M, Furst S, Michallet M, Bay JO, et al. Allogeneic hematopoeitic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis: a report of the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire. Brit J Hematol. 2010;10:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang DY, Deeg HJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for patients with myelofibrosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;15:140–146. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283257ab2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal P, Saliba RM, Giralt SA, Shahjahan M, Cohen AI, Karandish S, et al. Allogeneic transplantation: a therapeutic option for myelofibrosis, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and Philadelphia negative/bcr-abl negative chronic myelogeneous leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;3:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditschkowski M, Beelen DW, Trenschel R, Koldehoff M, Elmaagacli AH. Outcome of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with myelofibrosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34:807–813. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg HJ, Gooley TA, Flowers ME, Sale GE, Slattery JT, Anasetti C, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2003;102:3912–3918. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbauy DM, Gooley TM, Sale GE, Flowers ME, Doney KC, Georges GE, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation as curative therapy for idiopathic myelofibrosis, advanced polycythemia vera, and essential thrombocythemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly A, Song K, Nevill T, Nantel S, Toze C, Hogge D, et al. Stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis: a report from two Canadian centers. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:35–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91:756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey BR, McAfee S, Sackstein R, Colby C, Saidman S, Weymouth D, et al. Successful allogeneic stem cell transplantation with nonmyeloablative conditioning in patients with relapsed hematologic malignancy following autologous stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:604–612. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11760148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giralt S, Thall PF, Khouri I, Wang X, Braunschweig I, Ippolitti C, et al. Melphalan and purine analog-containing preparative regimens: reduced intensity conditioning for patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;97:631–637. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine SM, Hoffman R, Verma A, Shah R, Bradlow BA, Stock W, et al. Allogeneic blood cell transplantation following reduced intensity conditioning is effective therapy for older patients with myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2002;99:2255–2258. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondelli D, Barosi G, Bacigalupo A, Prchal JT, Popat U, Alessandrino EP, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning in intermediate-or high-risk patients with myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2005;105:4115–4119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger N, Holler E, Kobbe G, Bornhauser M, Schwedtfeger R, Baurmann H, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation after reduced-intensity conditioning in patients with myelofibrosis: a prospective, multicenter study of the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2009;114:5264–5270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrup M, Lazarevic V, Nahi H, Andreasson B, Malm C, Nilsson L, et al. Different outcome of allogeneic transplantation in myelofibrosis using conventional or reduced-intensity conditioning regimens. Brit J Hematol. 2006;135:367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DS, Palmer J, Gaal K, Pullarkat V, Sahebi F, Cohen S, et al. Improved outcomes using tacrolimus/sirolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant as treatment for myelofibrosis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart WA, Pearce R, Kirkland KE, Bloor A, Thomson K, Apperley J, et al. The role of allogeneic SCT in primary myelofibrosis: a British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1587–1593. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson S, Sandmaier BM, Heslop HE, Popat U, Carrum G, Champlin RE, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for myelofibrosis in 30 patients 60–78 years of age. Brit J Hematol. 2011;153:76–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballen KK, Spitzer TR. The great debate: haploidentical or cord blood transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:323–329. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballen KK, Spitzer TR, Yeap BY, McAfee S, Dey B, Attar E, et al. Double unrelated reduced intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation in adults. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S, Ota Y, Uchida N, Takahashi K, Ishiwata K, Tsuji M, et al. Successful engraftment after reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2010;116:649–652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacigalupo A, Soraru M, Dominietto A, Pozzi S, Geroldi S, Van Lint MT, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic SCT for patients with primary myelofibrosis: a predictive transplant score based on transfusion requirement, spleen size, and donor type. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:458–463. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott BL, Gooley TA, Linenberger ML, Sandmaier BM, Myerson D, Chauncey T, et al. International Working Group scores predict post-transplant outcomes in patients with myelofibrosis. Blood. 2010;116:965a (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ciurea SO, Sadegi B, Wilbur A, Alagiozian-Angelova V, Gaitonade S, Dobogai LC, et al. Effects of extensive splenomegaly in patients with myelofibrosis undergoing a reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Brit J Hematol. 2008;141:80–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akpek G, Pasquini MC, Agovi MA, Logan B, Cooke KR, Maziarz RT, et al. Spleen status and engraftment after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;116:3486a. [Google Scholar]

- Robin M, Esperous H, Peffault R, Petropoulou AD, Xhaard A, Ribauad P, et al. Splenectomy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with primary myelofibrosis. Brit J Hematol. 2010;150:721–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alchalby H, Badbaran A, Zabelina T, Kobbe G, Hahn J, Wolff D, et al. Impact of JAK2V617F mutation status, allele burden, and clearance after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis. Blood. 2010;116:3572–3581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-260588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steckel NK, Koldehoff M, Ditschkowski M, Beelen DW, Elmaagacli AH. Use of the activating gene mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 as a minimal disease marker in patients with myelofibrosis and myeloid metaplasia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83:1518–1520. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000263393.65764.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation versus drugs in myelofibrosis: the risk-benefit balancing act. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:419–421. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroger N, Mesa RA. Choosing between stem cell therapy and drugs in myelofibrosis. Leukemia. 2008;22:474–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya R, Caramazza C, Begna KH, Gangat N, VanDyke DL, Hanson CA, et al. Monosomal karyotype in primary myelofibrosis is detrimental to both overall and leukemia-free survival. Blood. 2011;117:5612–5615. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-320002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]