Abstract

Background

A shortage of primary care physicians (PCPs) seems likely in Germany in the near future and already exists in some parts of the country. Many currently practicing PCPs will soon reach retirement age, and recruiting young physicians for family practice is difficult. The attractiveness of primary care for young physicians depends on the job satisfaction of currently practicing PCPs. We studied job satisfaction among PCPs in Lower Saxony, a large federal state in Germany.

Methods

In 2009, we sent a standardized written questionnaire on overall job satisfaction and on particular aspects of medical practice to 3296 randomly chosen PCPs and internists in family practice in Lower Saxony (50% of the entire target population).

Results

1106 physicians (34%) responded; their mean age was 52, and 69% were men. 64% said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their job overall. There were particularly high rates of satisfaction with patient contact (91%) and working atmosphere (87% satisfied or very satisfied). In contrast, there were high rates of dissatisfaction with administrative tasks (75% dissatisfied or not at all satisfied). The results were more indifferent concerning payment and work life balance. Overall, younger PCPs and physicians just entering practice were more satisfied than their older colleagues who had been in practice longer.

Conclusion

PCPs are satisfied with their job overall. However, there is significant dissatisfaction with administrative tasks. Improvements in this area may contribute to making primary care more attractive to young physicians.

Compared with other European countries, Germany has an overall high density of physicians (1). However, as far as primary care physicians (PCPs) are concerned, a shortage is imminent—and in some regions, especially those with a less developed infrastructure, this is already reality. The main reason for this is the age structure of currently practicing PCPs and problems in recruiting young doctors into primary care (2, 3). On this background, the pertinent question is how attractive general practice is as a specialty; something that is crucially influenced by working conditions and earnings (4, 5).

Currently existing, non-representative, studies of the work satisfaction of doctors in Germany mainly focused on inpatient services (6, 7); only a few studies have focused on the situation of doctors in private practice, neither of specialists (8) nor of general practitioners (9– 11). Exploratory qualitative studies have shown that PCPs are dissatisfied in particular with working conditions (remuneration, administrative tasks) as well as professional acceptance and social recognition (12, 13). In the international comparison (14), 60% of PCPs in Germany are “somewhat dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied”, a notably worse rating than in other countries (for example, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France). However, these data relate only to overall job satisfaction, without any more differentiated consideration of partial aspects of the job.

The present study sought to empirically investigate the job satisfaction of PCPs overall as well as regarding certain selected aspects. We also wanted to analyze any association with doctor-related and practice-related sociodemographic factors.

Method

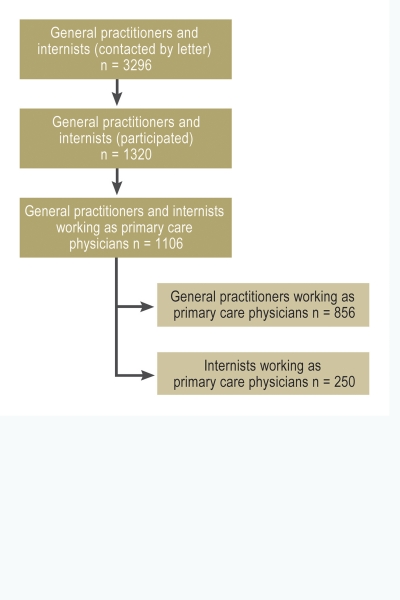

The data are based on a 50% sample, taken in the German state of Lower Saxony on a particular date (12 February 2009), of all general practitioners and specialists in internal medicine (“internists”) working as primary care physicians (PCPs) treating members of statutory health insurance schemes. The sample was derived from a primary data set from Lower Saxony’s regional Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KV Niedersachsen): 2254 general practitioners and 1042 internists were included. Later analyses included only those doctors who had reported working as PCPs (filtering question) (Figure).

Figure.

Response rates and participants

The survey was announced in Niedersächsisches Ärzteblatt (the journal of the Medical Association of Lower Saxony) as well as in the KV Niedersachsen’s bulletin. Participants were offered a fee of € 20, to cover their expenses. Non-participants were reminded twice, and in case of non-response they were asked for their reasons for not participating, on a stamped and addressed postcard.

The questionnaire contained data on the determinants of job satisfaction as described in the literature (9, 15). These were evaluated in a five-point scale ranging from “very satisfied” to “not at all satisfied”. In detail, doctors were asked for their satisfaction with the following aspects:

Overall job satisfaction

Professional challenges

Atmosphere at work

Contact with patients

Administrative tasks

Continuing medical education

Remuneration/pay

Hours worked

Autonomy

Compatibility of professional and personal life.

As sociodemographic variables relating to doctors and practices we collected age, sex, length of time worked as a doctor treating members of statutory health insurance schemes, location of practice, and type of practice.

After cleaning the data set and checking for plausibility, we analyzed the data using SPSS 18.0 for Windows. In order to calculate differences with regard to age, sex, length of time worked in the context of statutory health insurance schemes, type of practice, as well as with regard to general practitioners and internists, Pearson’s chi-square test was used. Differences of p<0.05 were defined as significant but should none the less be interpreted descriptively. Additionally, multivariate analyses (ordinal regression) was undertaken so as to determine associations between variables.

The study was part of a larger project, funded by the German Medical Association, which focuses on palliative medicine (as part of the German Medical Association’s health services research funding initiative). A possible influence of this study context on the results regarding job satisfaction will be debated in the discussion section.

The data protection officer of Hannover Medical School (MHH) monitored how the study was conducted. Ethics approval was granted by Hannover Medical School’s ethics committee.

Results

Responses from 1106 primary care physicians were evaluated; these included 856 general practitioners and 250 internists working as primary care physicians (response rate 34%) (Figure). Participants were mainly men (69%, n = 761), were on average 51 years old, and most had practiced as doctors treating members of statutory health insurance schemes for more than 10 years (64%, n = 701) (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic data for the participants (general practitioners and specialists in internal medicine working as primary care physicians; n = 1 106; excludes missing data).

| Characteristic | Detail | GPs | Internists | Total | |||

| % | abs. | % | abs. | % | abs. | ||

| Age group | 29–45 years | 22 | 186 | 35 | 86 | 25 | 272 |

| 46–60 years | 61 | 523 | 53 | 131 | 60 | 654 | |

| 61–76 years | 17 | 142 | 12 | 29 | 15 | 171 | |

| Sex | Female | 33 | 283 | 23 | 58 | 31 | 341 |

| Male | 67 | 570 | 77 | 191 | 69 | 761 | |

| Type of practice | Single-handed practice | 46 | 382 | 43 | 107 | 45 | 489 |

| Cooperative practice(group practice, outpatient medical center) | 54 | 454 | 57 | 140 | 55 | 594 | |

| Location of practice | Urban(>100 000 population) | 19 | 162 | 29 | 73 | 21 | 235 |

| Town(>20 000 population) | 28 | 240 | 37 | 92 | 30 | 332 | |

| Rural(<20 000 population) | 53 | 447 | 34 | 85 | 49 | 532 | |

| Length of time work‧ed as doctor treating members of stautory health insurance schemes | ≤10 years | 30 | 251 | 57 | 141 | 36 | 392 |

| >10 years | 70 | 594 | 43 | 107 | 64 | 701 | |

| Working hours | <40 hours per week | 12 | 105 | 10 | 25 | 12 | 130 |

| 40–60 hours per week | 60 | 500 | 58 | 143 | 59 | 643 | |

| >60 hours per week | 28 | 232 | 32 | 80 | 29 | 312 | |

| No of patients ‧treated*1 | <500 | 4 | 39 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 52 |

| 500–999 | 34 | 284 | 38 | 92 | 34 | 376 | |

| ≥1000 | 62 | 519 | 57 | 141 | 61 | 660 | |

*1relating to previous quarter; abs.: absolute frequencies; %: relative (proportional) frequency; GP, general practitioner

The participating general practitioners and internists differed with regard to the following sociodemographic variables:

A higher proportion of women among general practitioners (p = 0.003),

A higher average age among internists (p<0.001),

The proportion of internists who had worked in primary care private practice for less than 10 years was higher than that of general practitioners (p<0.001),

Internists working as primary care physicians were mostly based in urban regions compared with general practitioners (p<0.001).

Overall job satisfaction of primary care physicians

Altogether 64% of participating primary care physicians reported being “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with their jobs. When stratifying by age group, it becomes obvious that job satisfaction is highest in the group aged 29 to 45 years (73% very satisfied or satisfied). In over-45-year-old doctors treating members of statutory health insurance schemes, job satisfaction is slightly lower (Table 2).

Table 2. Satisfaction of primary care physicians (general practitioners and internists).

| Aspect | Very satisfied/ satisfied | Partially satisfied | Not at all/ not satisfied | Significance p*1 | |||||

| % | abs. | % | abs. | % | abs. | ||||

| Overall job satisfaction | Age | 29–45 years | 73 | 195 | 24 | 63 | 3 | 8 | <0.001 |

| 46–60 years | 60 | 375 | 28 | 179 | 12 | 75 | |||

| 61–76 years | 66 | 111 | 26 | 44 | 8 | 13 | |||

| Total | 64 | 681 | 27 | 286 | 9 | 96 | |||

| Length of time worked as a doctor treating members of statutory health insurance schemes | ≤10 years | 69 | 263 | 26 | 99 | 5 | 19 | <0.001 | |

| >10 years | 61 | 413 | 29 | 187 | 11 | 77 | |||

| Total | 64 | 676 | 27 | 286 | 9 | 96 | |||

| Contact with patients | Age | 29–45 years | 87 | 236 | 11 | 30 | 2 | 4 | <0.05 |

| 46–60 years | 90 | 587 | 8 | 50 | 2 | 11 | |||

| 61–76 years | 96 | 163 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Total | 91 | 986 | 8 | 86 | 1 | 15 | |||

| Length of time worked as a doctor treating members of statutory health insurance schemes | ≤10 years | 87 | 337 | 12 | 46 | 1 | 6 | <0.005 | |

| >10 years | 93 | 645 | 6 | 39 | 1 | 9 | |||

| Total | 91 | 982 | 8 | 85 | 1 | 15 | |||

| Compatibility of professional and personal life | Age | 29–45 years | 42 | 112 | 33 | 89 | 25 | 66 | <0.005 |

| 46–60 years | 31 | 202 | 32 | 208 | 37 | 235 | |||

| 61–76 years | 40 | 68 | 35 | 60 | 25 | 42 | |||

| Total | 35 | 382 | 33 | 357 | 32 | 343 | |||

| Working hours | Age | 29–45 years | 40 | 106 | 31 | 84 | 29 | 77 | <0.001 |

| 46–60 years | 31 | 200 | 25 | 163 | 44 | 280 | |||

| 61–76 years | 42 | 70 | 26 | 44 | 32 | 53 | |||

| Total | 35 | 376 | 27 | 291 | 38 | 410 | |||

| Remuneration/pay | Age | 29–45 years | 35 | 93 | 30 | 81 | 35 | 94 | <0.001 |

| 46–60 years | 27 | 173 | 27 | 176 | 46 | 297 | |||

| 61–76 years | 24 | 40 | 19 | 33 | 57 | 98 | |||

| Total | 28 | 306 | 27 | 290 | 45 | 489 | |||

| Type of practice | Single-handed practice | 24 | 116 | 23 | 111 | 53 | 254 | <0.001 | |

| Cooperative practice | 31 | 181 | 29 | 175 | 40 | 233 | |||

| Total | 28 | 297 | 27 | 286 | 45 | 487 | |||

| Administrative tasks | Length of time worked as a doctor treating members of statutory health insurance schemes | ≤10 years | 7 | 29 | 25 | 95 | 68 | 262 | <0.05 |

| >10 years | 7 | 47 | 15 | 101 | 78 | 539 | |||

| Total | 7 | 76 | 18 | 196 | 75 | 801 | |||

| Practice atmosphere | Age | 29–45 years | 91 | 245 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 7 | 0.128 |

| 46–60 years | 85 | 550 | 12 | 75 | 3 | 21 | |||

| 61–76 years | 85 | 145 | 12 | 21 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Total | 87 | 940 | 10 | 113 | 3 | 32 | |||

| Professional challenges | Age | 29–45 years | 84 | 225 | 14 | 37 | 2 | 6 | 0.115 |

| 46–60 years | 82 | 524 | 16 | 101 | 2 | 15 | |||

| 61–76 years | 90 | 153 | 8 | 13 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Total | 84 | 902 | 14 | 151 | 2 | 25 | |||

| Continuing medical education | Age | 29–45 years | 51 | 136 | 41 | 110 | 8 | 23 | <0.001 |

| 46–60 years | 58 | 372 | 36 | 233 | 6 | 36 | |||

| 61–76 years | 72 | 120 | 20 | 34 | 8 | 13 | |||

| Total | 58 | 628 | 35 | 377 | 7 | 72 | |||

| Autonomy | Age | 29–45 years | 44 | 118 | 30 | 80 | 26 | 69 | <0.001 |

| 46–60 years | 34 | 220 | 23 | 145 | 43 | 278 | |||

| 61–76 years | 36 | 61 | 23 | 38 | 41 | 69 | |||

| Total | 37 | 399 | 24 | 263 | 39 | 416 | |||

*1Pearson’s chi-square test; abs., absolute frequency; %, relative (proportional) frequency

With regard to the length of time worked within the context of statutory health insurance schemes, the “novices” were slightly more satisfied with their jobs. Only 5% of those working within the context of such schemes for less than 10 years were not satisfied or not at all satisfied, compared with more than 11% of those who had done it for more than 10 years. No differences between groups were found for the other demographic, physician-related, or practice-related characteristics.

Our multivariate analyses confirmed the results of the bivariate analyses but contributed only very little towards explaining the variance (<3%, R2 according to Nagelkerke).

Satisfaction with individual aspects of the job

When considering individual aspects of job satisfaction, distinction can be made between high satisfaction, medium satisfaction, and low satisfaction.

Aspects of high satisfaction

91% reported being satisfied or very satisfied with patient contact. The degree of satisfaction correlates with the length of time worked as doctors treating members of statutory health insurance schemes and doctors’ age (Table 2).

87% of primary care physicians were satisfied or very satisfied with the working atmosphere.

84% of participants were satisfied or very satisfied with the professional challenges (Table 2).

Aspects of average satisfaction

45% of participating doctors reported being dissatisfied or not at all satisfied with their remuneration. By contrast, 28% reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pay. Doctors in single-handed practices were slightly more dissatisfied than those working in cooperative practices. In terms of the different age groups, older doctors reported being more dissatisfied (Table 2).

35% of participants reported being able to reconcile their professional and personal lives; 32% reported being dissatisfied in this regard. Satisfaction with the compatibility of professional and personal life is highest in the group aged 29 to 45, but similarly high in the group aged 61 to 76 (Table 2).

Responses regarding satisfaction with working hours were wide ranging: 38% of participants were not satisfied/not at all satisfied, 27% were so/so, and 35% satisfied or very satisfied. The different age groups rated working hours very differently, the group aged 46 to 60 was least satisfied (Table 2). Satisfaction among women doctors did not differ from that of their male colleagues, but they often worked less than 40 hours per week, whereas more men reported working more than 60 hours per week (p<0.001). The largest groups of men and women (60% of men, n = 446; 59% of women, n = 195) reported working 40 to 60 hours per week.

58% were satisfied or very satisfied with the provision of continuing medical education, 35% were so/so. The oldest group of participants—those aged 61 to 76—was most satisfied (Table 2).

37% were satisfied or very satisfied with the aspect of autonomy, but 39% were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied in that respect. Age specific differences exist: Older doctors were more dissatisfied with autonomy in their professional activities than younger ones (Table 2).

Aspects of professional activity with high degrees of dissatisfaction

The greatest degree of dissatisfaction by some margin was expressed with regard to administrative tasks. 75% of primary care physicians reported that they were not satisfied or not at all satisfied in this respect. Doctors who had been practicing for more than 10 years were slightly more dissatisfied than those who had been practicing for less than 10 years (Table 2).

Comparison between general practitioners and internists working as primary care physicians

With regard to their satisfaction with their remuneration and administrative tasks, differences exist between general practitioners and internists (Table 3). The latter were more likely to be satisfied with their remuneration and less likely to be dissatisfied with their administrative burden. In further partial aspects of job satisfaction, no differences were found between the two groups.

Table 3. Satisfaction of general practitioners and specialists in internal medicine working as primary care physicians.

| General practitioners | Specialists in internal medicine working as PCPs | Significance p*1 | ||||

| % | abs. | % | abs. | |||

| Job satisfaction | Not at all satisfied | 10 | 83 | 5 | 13 | 0.064 |

| Partially satisfied | 26 | 217 | 29 | 71 | ||

| Very satisfied | 64 | 524 | 66 | 163 | ||

| Contact with patients | Not at all satisfied | 1 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 0.565 |

| Partially satisfied | 8 | 64 | 9 | 22 | ||

| Very satisfied | 91 | 768 | 90 | 226 | ||

| Compatibility of professional and personal life | Not at all satisfied | 31 | 260 | 34 | 85 | 0.622 |

| Partially satisfied | 33 | 279 | 32 | 80 | ||

| Very satisfied | 36 | 302 | 34 | 84 | ||

| Working hours | Not at all satisfied | 38 | 319 | 37 | 92 | 0.971 |

| Partially satisfied | 27 | 226 | 28 | 68 | ||

| Very satisfied | 35 | 293 | 35 | 87 | ||

| Remuneration/pay | Not at all satisfied | 47 | 401 | 36 | 90 | <0.001 |

| Partially satisfied | 27 | 225 | 28 | 69 | ||

| Very satisfied | 26 | 218 | 36 | 90 | ||

| Administrative Tasks | Not at all satisfied | 77 | 640 | 68 | 167 | 0.002 |

| Partially satisfied | 16 | 134 | 26 | 64 | ||

| Very satisfied | 8 | 63 | 6 | 16 | ||

| Practice atmosphere | Not at all satisfied | 3 | 25 | 3 | 7 | 0.757 |

| Partially satisfied | 11 | 91 | 99 | 23 | ||

| Very satisfied | 86 | 727 | 88 | 220 | ||

| Professional challenges | Not at all satisfied | 2 | 19 | 2 | 6 | 0.894 |

| Partially satisfied | 14 | 115 | 15 | 37 | ||

| Very satisfied | 84 | 703 | 83 | 206 | ||

| CME | Not at all satisfied | 7 | 61 | 5 | 12 | 0.409 |

| Partially satisfied | 35 | 290 | 35 | 87 | ||

| Very satisfied | 58 | 487 | 60 | 148 | ||

| Autonomy | Not at all satisfied | 39 | 328 | 36 | 90 | 0.296 |

| Partially satisfied | 23 | 196 | 28 | 70 | ||

| Very satisfied | 38 | 314 | 36 | 88 | ||

*1Pearson’s chi square test Quadrat; abs., absolute frequency; %, relative (proportional) frequency; CME, continuing medical education

Discussion

In the present study, more than 1100 primary care physicians in private practice in Lower Saxony were asked about their job satisfaction. 64% of participating doctors were overall satisfied or very satisfied. This high degree of satisfaction contradicts the tenor of a recently published study (14), according to which only 39% of primary care physicians are satisfied or even very satisfied with their own professional situation.

Both studies were conducted in 2009; the political framework conditions that might have influenced doctors’ job satisfaction are therefore comparable. However, different study designs may be partly responsible for the differences: The study reported by Koch et al. (14) was conducted in the setting of an international project studying quality in health care, and job satisfaction was one aspect in addition to rating the healthcare system, appointment systems, and other, politically oriented, aspects. Our study was borne out of a questionnaire study in the palliative setting. The questions regarding job satisfaction were posed in the concluding section of the questionnaire, without any prior focus in the announcement of the survey. The different focus of the overarching research projects may have influenced decisions in favor of or against participation as well as the response behavior.

The results from the present study—of satisfaction with their professional situation among a majority of primary care physicians—is supported by other German studies (10, 16, 17); however, regional differences have also been reported (18). The lower degree of satisfaction among female primary care physicians regarding partial aspects of job satisfaction (e.g. continuing education opportunities) was not confirmed in our study. Furthermore, effects with regard to age and length of time worked as a doctor were as good as negligible.

Administrative tasks

The extent of administrative tasks was rated as too high and burdensome in numerous studies (8, 15, 17, 18). Urgent attempts should be made to change this situation, in order to make working as a doctor more attractive. The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians has reacted to this criticism—which is by no means new—with an independent department for regulation (9, 19). On the other hand, the introduction of outpatient coding guidelines, for example, has introduced additional bureaucratic challenges, which have resulted in a notable increase in administrative tasks and are therefore subject to criticism from primary care physicians (20, 21).

Continuing medical education

Most doctors reported that they were satisfied with the provision of continuing medical educational options. This satisfaction, however, presumably does not contradict the often expressed criticism of continuing medical education for primary care physicians (5), since the physicians included in the present study have already completed their specialist training. The satisfaction with the continuing medical educational options provided is confirmed by a recent study from Bremen, but the results of this study cannot simply be extrapolated to the situation in rural Lower Saxony (23).

Professional and personal lives

In this study, a third of primary care physicians were satisfied with the compatibility of their professional and personal lives, one third responded so/so, and one third reported dissatisfaction. In a similar survey of female doctors in private practice in Lower Saxony from 2002, 40% of the women doctors reported that they did not have any children of their own (17)—in the free-text responses, they expressed the desire for improved maternity leave for doctors in private practice and a simplified process for employing locums. These demands are still valid and, on the background of an increasing proportion of women doctors, are gaining further importance, and not only for primary care.

Remuneration/pay

General practitioners working as primary care physicians are less satisfied with their remuneration than internists working as PCPs. Data from the German Federal Statistical Office show that general practitioners (practice owners) have net incomes of € 116 000 per year (20), which places them in the lower range of earnings within medical specialties. Comparisons between the incomes of general practitioners and internists working as PCPs are not available—whether actually existing differences in income might explain the greater dissatisfaction is not clear. How relevant the association between monetary aspects and job satisfaction actually is, has been the subject of controversy (7, 24)—overall, income seems to affect job satisfaction to a rather negligible degree, except where remuneration is extremely low (“hygiene factor”). In this sense, monetary enticements may help avoid dissatisfaction while not actually contributing much to greater job satisfaction.

Strengths and limitations of our study

The strengths include the large sample size and the high response rate for a study of this type of study in the German-speaking regions—namely, 34% in a large region such as the state of Lower Saxony. Still, response bias cannot be excluded, especially when considering that the study was embedded in a study of palliative medical services. Such embedding may be regarded as both a strength and a limitation: On the one hand, the primary motivation for participation was not the topic of job satisfaction, but on the other hand, no in-depth—or open—questions regarding job satisfaction were possible. Complementary qualitative studies or narrative reports are required in this context, which can provide further insights into aspects of job satisfaction that were not considered in this and other studies (25).

Compared with other studies, the present study had a large sample and captured the target group in a more systematic fashion than Götz (10), as all primary care physicians in private practice in an entire region were included. A selection bias of those who were particularly dissatisfied with their financial situation owing to the moderate expense fee of € 20 seems unlikely. In the study reported by Koch et al. (14), the same amount was offered to cover participants’ expenses, but on the whole, the participants in that study were notably more dissatisfied. Still, a bias owing to doctors dissatisfied overall or with individual partial aspects of their job cannot be ruled out.

Regional factors such as the density of physicians or healthcare structures developed following alternative models (for example, primary care physician centered care) may affect job satisfaction. At the time we conducted our survey, however, Lower Saxony had no such structures that might have affected the results.

Conclusion and outlook

According to this study, job satisfaction among primary care physicians is better than expected. The divergent opinions expressed regarding partial aspects of job satisfaction, however, clearly point at areas that require much improvement. This concerns primarily administrative tasks. Politicians and doctors’ self-governance bodies might be well advised to use this as a starting point for making primary care a more attractive career option and counteract the threat of a shortage of primary care physicians.

Key Messages.

64% of participating primary care physicians were overall satisfied or very satisfied with their jobs.

45% of participating primary care physicians were dissatisfied or not at all satisfied with their pay.

Primary care physicians expressed particular dissatisfaction (75%) with administrative tasks.

Specialists in internal medicine working as primary care physicians were less dissatisfied with their remuneration and administrative tasks than general practitioners.

Older doctors were slightly less satisfied in terms of their autonomy regarding their professional activities than their younger colleagues.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Dr Birte Twisselmann.

The project was funded by the German Medical Association in the context of the Förderinitiative Versorgungsforschung (health services research funding initiative). The authors thank all physicians who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Koch K, Gehrmann U, Sawicki PT. Primärärztliche Versorgung in Deutschland im internationalen Vergleich: Ergebnisse einer strukturvalidierten Ärztebefragung. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104(38):2584–2591. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopetsch T. 5th edition. Berlin: Bundesärztekammer und Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung; 2010. Dem deutschen Gesundheitswesen gehen die Ärzte aus! [Google Scholar]

- 3.KBV - Deutschlandweite Arztzahlen im Überblick - Deutschlandweite Arztzahlen. http://www.kbv.de/wir_ueber_uns/4131.html.

- 4.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:502–512. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmacke N. Die Sicherung der hausärztlichen Versorgung in der Perspektive des ärztlichen Nachwuchses und niedergelassener Hausärztinnen und Hausärzte. www.akg.uni-bremen.de [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mache S, Vitzthum K, Nienhaus A, Klapp BF, Groneberg DA. Physicians’ working conditions and job satisfaction: does hospital ownership in Germany make a difference? BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janus K, Amelung VE, Gaitanides M, Schwartz FW. German physicians „on strike“-shedding light on the roots of physician dissatisfaction. Health Policy. 2007;82:357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berberich HJ, Brähler E. Life satisfaction, health status, and professional satisfaction of urologists in private practice. Urologe A. 2006;45:936–938. doi: 10.1007/s00120-006-1123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gothe H, Köster A-D, Storz P, Nolting H-D, Häussler B. Arbeits- und Berufszufriedenheit von Ärzten: Eine Übersicht der internationalen Literatur. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104(20):1394–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Götz K, Broge B, Willms S, Joos S, Szecsenyi J. Job satisfaction of general practitioners. Med Klin. 2010;105:767–771. doi: 10.1007/s00063-010-8881-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van den Bussche H Arbeitsbedingungen und Befinden von Ärztinnen und Ärzten. Report Versorgungsforschung 2. 1st edition. Köln: Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2009. Arbeitsbelastung und Berufszufriedenheit bei niedergelassenen Ärztinnen und Ärzten: Genug Zeit für die Patientenversorgung? Befunde und Interventionen. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Natanzon I, Ose D, Szecsenyi J, Joos S. What factors aid in the recruitment of general practice as a career? An enquiry by interview of general practitioners. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2010;135:1011–1015. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natanzon I, Szecsenyi J, Ose D, Joos S. Future potential country doctor: the perspectives of German GPs. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch K, Miksch A, Schürmann C, Joos S, Sawicki PT. The German Health Care System in international comparison: the primary care physicians´ perspective. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(15):255–261. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Ham I, Verhoeven AAH, Groenier KH, Groothoff JW, De Haan J. Job satisfaction among general practitioners: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12:174–180. doi: 10.1080/13814780600994376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schäfer H-M, Krentz H, Harloff R. Berufszufriedenheit von Allgemeinärzten in Deutschland und Frankreich - eine vergleichende Untersuchung in 3 Großstädten. Z Allg Med. 2005;81:284–288. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goesmann C, Sens B, Heidrich S, Glowienka-Wiedenroth F. Hohe Berufszufriedenheit bei niedergelassenen Ärztinnen! Niedersächsisches Ärzteblatt. 2002;75:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schäfer H-M, Becker A, Krentz H, Reisinger E. Wie zufrieden sind Hausärzte im Nordosten Deutschlands mit ihrem Beruf? - Ein Survey zur Berufszufriedenheit von Allgemeinärzten in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2008;102:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 19.KBV - Presseecho 2009 - KBV will Bürokratie abbauen. www.kbv.de//25420.html.

- 20.Popert U, Claus C. Ambulante Kodierrichtlinien - Zeit für Verbesserungen. Der Allgemeinarzt. 2011;5:60–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DEGAM-Stellungnahme_zu_Kodierrichtlinien.pdf. www.degam.de/uploads/media/101216_DEGAM-Stellungnahme_zu_Kodierrichtli-nien.pdf.

- 22.Kempkens D, Dieterle WE, Butzlaff M, et al. German ambulatory care physicians’ perspectives on continuing medical education-a national survey. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:259–268. doi: 10.1002/chp.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egidi G, Biesewig-Siebenmorgen J, Schmiemann G. 5 Jahre Akademie für hausärztliche Fortbildung Bremen - Rückblick und Perspektiven. Z Allg Med. 2011;87:459–467. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grumbach K, Osmond D, Vranizan K, Jaffe D, Bindman AB. Primary care physicians’ experience of financial incentives in managed-care systems. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1516–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurzke U. Berufszufriedenheit und Zukunft der Versorgung. Z Allg Med. 2011;87:152–157. [Google Scholar]