Abstract

Neurotrophins and their receptors adopt signaling endosomes to transmit retrograde signals. However, the mechanisms of retrograde signaling for other ligand/receptor systems are poorly understood. Here, we report that the signals of the purinergic (P)2X3 receptor, an ATP-gated ion channel, are retrogradely transported in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neuron axons. We found that Rab5, a small GTPase, controls the early sorting of P2X3 receptors into endosomes, while Rab7 mediates the fast retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors. Intraplantar injection and axonal application into the microfluidic chamber of α, β-methylene-ATP (α, β-MeATP), a P2X selective agonist, enhanced the endocytosis and retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors. The α, β-MeATP-induced Ca2+ influx activated a pathway comprised of protein kinase C, rat sarcoma viral oncogene and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK), which associated with endocytic P2X3 receptors to form signaling endosomes. Disruption of the lipid rafts abolished the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation, endocytosis and retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors. Furthermore, treatment of peripheral axons with α, β-MeATP increased the activation level of ERK and cAMP response element-binding protein in the cell bodies of DRG neurons and enhanced neuronal excitability. Impairment of either microtubule-based axonal transport in vivo or dynein function in vitro blocked α, β-MeATP-induced retrograde signals. These results indicate that P2X3 receptor-activated signals are transmitted via retrogradely transported endosomes in primary sensory neurons and provide a novel signaling mechanism for ligand-gated channels.

Keywords: P2X3 receptor, retrograde transport, Rab7, signaling endosomes, lipid raft

Introduction

Neurons extend long axons for long-distance communication between distal terminals and cell bodies. Axonal transport is thus crucial for neuronal growth, survival and synaptic plasticity 1. Motor proteins from the kinesin and dynein superfamilies generate the necessary force for microtubule-based axonal transport in anterograde and retrograde directions, respectively 2, 3. Accumulating evidence indicates that signals for target-derived neurotrophins and their receptors are transmitted via a form of “signaling endosomes” in neuron axons 4. The transmission of retrogradely transported endosomal signaling is a multi-step process that includes the endocytosis of ligand-receptor complex at axon terminals, the formation of active signaling endosomes and dynein-mediated retrograde transport to the cell body. Signaling molecules, such as phospholipase C, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, have been found in endosomes containing nerve growth factor (NGF) and its activated receptor tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) 4. These specialized endosomes are retrogradely transported to the cell body and activate transcription factors, such as cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) 5 and ETS-like transcription factor 1 (ELK-1) 6, to regulate gene expression and neuronal functions.

Although retrograde signaling within the neurotrophin-receptor system is well established, little is known about how other ligand-receptor systems in neurons transmit their signals over long distances. Purinergic (P)2X receptors are adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-gated cation channels that play important roles in pathophysiological processes 7. Among the seven isoforms in the P2X receptor subfamily, the P2X3 receptor is abundantly expressed in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons 8, which are pseudounipolar neurons with two branches of axons extending to the spinal cord and periphery. Previous nerve ligation experiments have shown that synthesized P2X3 receptors can be transported to both central and peripheral terminals in DRG neurons 8, 9. Thus, ATP released from sympathetic nerves, endothelial cells, Merkel cells and tumor cells could induce currents after binding to P2X3 receptors at the nerve terminals 10. Further results from experiments using antisense oligonucleotides 11, 12, antagonists 13 or genetic knockouts 14, 15 have revealed that the P2X3 receptor participates in neuropathic and inflammatory pain.

P2X receptors are permeable to small cations, including Ca2+. Activation of P2X3 receptors in the peripheral terminals of DRG neurons produces action potentials via Ca2+ influx, and this mechanism has been proposed to activate nociceptors and transmit primary sensation 16. Importantly, action potentials generated at the nerve terminals could activate MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) and CREB in DRG neurons 17. Intracellular signaling pathways in DRG neurons are involved in pain under both normal and pathological conditions. The elevated ERK signal in the cell bodies and peripheral nerve fibers of DRG neurons contributes to the P2X3 receptor-mediated mechanical sensitivity of inflamed joints 18. Usually, the ATP-induced effect mediated by P2X receptors is thought to initiate within minutes. However, the mechanism for the long-distance and long-term purinergic signaling mediated by P2X receptor is unclear and requires further investigation.

In this study, we report that P2X3 receptors are retrogradely transported in DRG neuron axons. The long-distance transport of P2X3 receptors is mediated by Rab7 endosomes. Both the endocytosis and retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors are ligand dependent. Retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors associate with activated MAPK/ERK signaling molecules to form signaling endosomes that further increase the activation level of ERK and CREB in the cell bodies of DRG neurons following α, β-MeATP application to nerve terminals. In addition, we show that lipid rafts are involved in both the formation of P2X3 receptor-containing signaling endosomes and the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors. Our study reveals a novel mechanism for the signaling of a ligand-gated ion channel via retrogradely transported endosomes.

Results

Retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors in the axons of DRG neurons

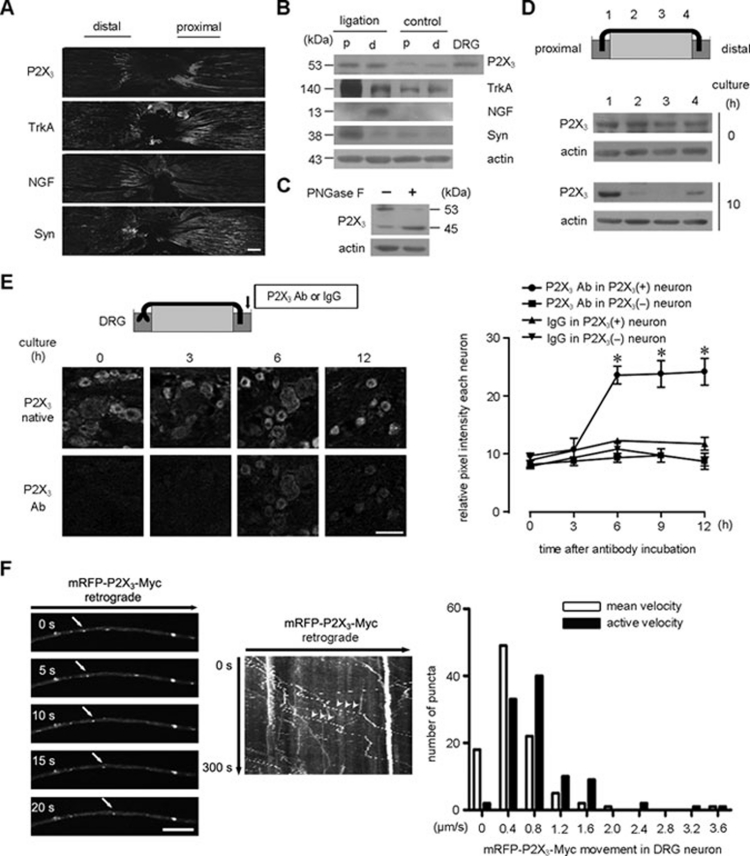

A sciatic nerve ligation model was prepared to determine whether P2X3 receptors could be retrogradely transported in vivo, similar to the neurotrophin receptor TrkA. Synaptophysin and NGF were used as the positive anterograde and retrograde control, respectively. Consistent with previous reports 6, 19, 20, immunohistochemistry and western blot experiments showed a dominantly proximal accumulation of synaptophysin (anterograde transport), an exclusively distal accumulation of NGF (retrograde transport) and both a proximal and distal accumulation of TrkA (bidirectional transport) (Figure 1A and 1B). Interestingly, a large number of P2X3 receptors accumulated in the distal nerve segment and the proximal segment of the ligated sciatic nerve (Figure 1A and 1B). The molecular weight of the detected P2X3 receptors in both the proximal and distal segments was ∼53 kD, which is consistent with the molecular weight of the P2X3 receptors in DRG neurons (Figure 1B). PNGase F, an enzyme that removes all types of N-linked glycosylation, shifted the P2X3 receptor-positive band to 45 kD (Figure 1C), the predicted molecular weight of this receptor. Thus, the P2X3 receptor that is transported in sciatic nerves is a glycosylated and non-degraded form. To minimize the effects of local ischemia and nerve injury caused by sciatic nerve ligation, we prepared a sciatic nerve-culture chamber, as previously reported 6. Prior to incubation, P2X3 receptors were distributed equally among four segments (Figure 1D). Following a 10-h culture, P2X3 receptors gradually accumulated in both terminal segments (Figure 1D), further demonstrating the bidirectional transport of this receptor in sciatic nerves. Based on a recent study 21, we co-cultured DRG with sciatic nerve and incubated the nerve end with a rabbit antibody against the C-terminus of the P2X3 receptor for 0, 3, 6, 9 or 12 h. The signals of retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors were detected within the P2X3 receptor-positive DRG neurons at 6 h after culture and lasted up to 12 h. However, these signals were not detected in the P2X3 receptor-negative neurons (Figure 1E). The signal was also not observed in the P2X3 receptor-positive neurons treated with a rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) that served as the control (Figure 1E; Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Based on nerve length, the fastest velocity of the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor was estimated to be ∼1.4 μm/s, which is in the range of fast retrograde transport 1. Taken together, these data indicate that the P2X3 receptor is indeed retrogradely transported in sciatic nerve.

Figure 1.

The P2X3 receptor is retrogradely transported in the axons of DRG neurons. (A, B) Sciatic nerves were ligated at the middle-thigh level and processed for immunostaining and immunoblotting. Similar to TrkA, P2X3 receptors accumulated at the distal (d) and proximal (p) segments of the ligated nerves. NGF and synaptophysin (Syn) accumulated at the distal and proximal segments, respectively. Actin served as a loading control. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) PNGase F treatment shifted the P2X3 receptors in the DRG lysate from 53 kD to predominantly 45 kD, which is consistent with the predicted molecular weight of this receptor. (D) The freshly dissected and cultured nerves were cut into four segments. P2X3 receptors accumulated at both the proximal and distal segments after culture. (E) The distal end of the sciatic nerve connected with DRG was incubated with a P2X3 receptor antibody or a control IgG for the indicated time. The signal for retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors in DRG neurons became visible in the receptor-positive neurons at 6 h and lasted up to 12 h after culture. Scale bar, 30 μm. * P < 0.05 versus the signal in P2X3 receptor-negative neurons at 6, 9 or 12 h (n = 3). (F) Live cell imaging showed the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors (arrowheads) in cultured DRG neuron axons. The mean and active retrograde velocity profiles were assembled with 97 puncta. Scale bar, 5 μm.

To investigate the axonal transport kinetics of P2X3 receptors using live cell imaging, we obtained a P2X3 receptor plasmid that contained a Myc tag in the extracellular loop and a GFP tag at the C-terminus (P2X3-Myc-GFP) 22. We also made an mRFP version (mRFP-P2X3-Myc with an mRFP tag at the N-terminus). The functionality of both P2X3-Myc-GFP and mRFP-P2X3-Myc was verified by electrophysiological testing (Supplementary information, Figure S1B). Forty-eight hours after electroporation into cultured DRG neurons, mRFP-P2X3-Myc displayed a bright puncta distribution in the axons (Figure 1F), similar to TrkA-GFP (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). Time-lapse imaging showed that the mRFP-P2X3-Myc-containing puncta moved rapidly in both anterograde and retrograde directions (Figure 1F, Supplementary information, Movie S1), as did TrkA-GFP (Supplementary information, Figure S1C and Movie S2). We classified every punctum into one of the following five groups: 1) retrograde, punctum moves toward the cell body in all frames; 2) anterograde, punctum moves toward the axon terminal in all frames; 3) stationary, punctum shows no sign of movement; 4) jiggling, punctum displays side-to-side oscillatory motion and has no displacement; or 5) bidirectional, punctum moves both anterogradely and retrogradely and has a small displacement in all frames. Stationary, jiggling and bidirectional were considered to be non-significant movement. Mean retrograde velocity was calculated for each punctum, including the processes of movement and pause, and the activated velocity represents only the moving portion of the same punctum. We observed that 55.6% ± 5.0% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta (N = 363 puncta, n = 3) moved in the retrograde direction, and the mean retrograde velocity and the velocity during active retrograde movement were 0.61 ± 0.06 μm/s and 0.71 ± 0.05 μm/s, respectively. For TrkA-GFP, 57.8% ± 3.8% puncta (N = 467, n = 3) showed retrograde transport, and the mean and active retrograde velocities were 0.68 ± 0.02 μm/s and 1.04 ± 0.01 μm/s, respectively. These data suggest that the P2X3 receptor displays a similar mode of retrograde transport as the TrkA receptor in the axons of DRG neurons.

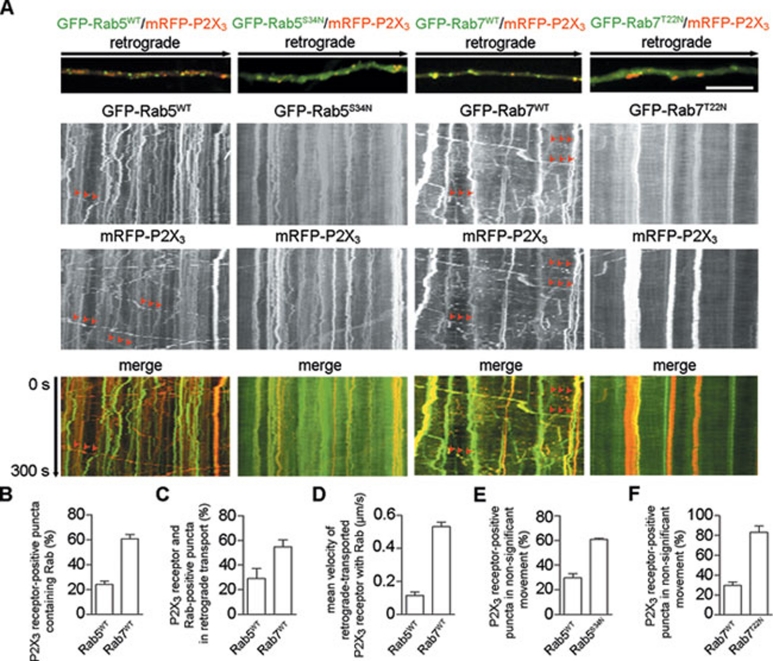

Late endosomes carry the long-distance retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors

Retrogradely transported proteins in the neuron axons can be carried by early or late endosomes. We next defined the roles of Rab5/Rab7 in mediating the retrograde transport of the P2X3 receptor. In the axons of cultured DRG neurons co-expressing GFP-tagged wild-type Rab5 (GFP-Rab5WT) and mRFP-P2X3-Myc, GFP-Rab5WT-positive puncta were stationary or displayed only short-distance movements (Figure 2A). In addition, 24.4% ± 2.6% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta (N = 487, n = 3) co-localized with GFP-Rab5WT (Figure 2A and 2B). However, 60.7% ± 3.5% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta (N = 348, n = 3) contained GFP-tagged wild-type Rab7 (GFP-Rab7WT) (Figure 2A and 2B). Moreover, 54.8% ± 5.7% of puncta co-expressing mRFP-P2X3-Myc and GFP-Rab7WT were involved in long-distance retrograde transport (Figure 2A and 2C; Supplementary information, Movie S3), in contrast to the 29.1% ± 8.1% of puncta co-expressing RFP-P2X3-Myc and GFP-Rab5WT (Figure 2A and 2C; Supplementary information, Movie S4). Kinetic analysis of puncta co-expressing GFP-Rab7WT and mRFP-P2X3-Myc showed an average retrograde velocity of 0.53 ± 0.03 μm/s (Figure 2D), similar to that of puncta expressing mRFP-P2X3-Myc alone. In contrast, mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta containing GFP-Rab5WT displayed a much slower average retrograde velocity of 0.12 ± 0.03 μm/s (Figure 2D). Furthermore, a dominant-negative Rab7 mutant, GFP-Rab7T22N, caused 83.3% ± 6.2% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta (N = 475, n = 3) to engage in non-significant movement (Figure 2A and 2F; Supplementary information, Movie S5), in contrast to 29.6% ± 3.4% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta in the axons of DRG neurons co-transfected with GFP-Rab7WT (Figure 2F). Importantly, a dominant-negative Rab5 mutant, GFP-Rab5S34N, resulted in 60.8% ± 1.0% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta (N = 746, n = 3) showing non-significant movement (Figure 2A and 2E; Supplementary information, Movie S6), in contrast to 29.7% ± 3.4% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta in the axons of DRG neurons co-transfected with GFP-Rab5WT (Figure 2E). Taken together, these results suggest that the P2X3 receptor is carried by early and late endosomes, but only the latter are responsible for the long-distance retrograde transport.

Figure 2.

Retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors are carried by late endosomes. (A) mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta containing GFP-Rab7WT, but not GFP-Rab5WT, displayed long-distance retrograde transport in live cell imaging (arrows). However, both dominant-negative Rab7 and Rab5 mutants disrupted the retrograde movement of most mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta. Scale bar, 5 μm. The percentages of P2X3 receptors co-localized with the wild-type Rab5 and Rab7 are shown in (B). The percentage and mean velocity of the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors co-localized with the wild-type Rab5 or Rab7 are presented in (C, D). The percentages of P2X3 receptors showing non-significant movement in the axons expressing wild-type versus dominant-negative Rabs are shown in (E) for Rab5 or in (F) for Rab7.

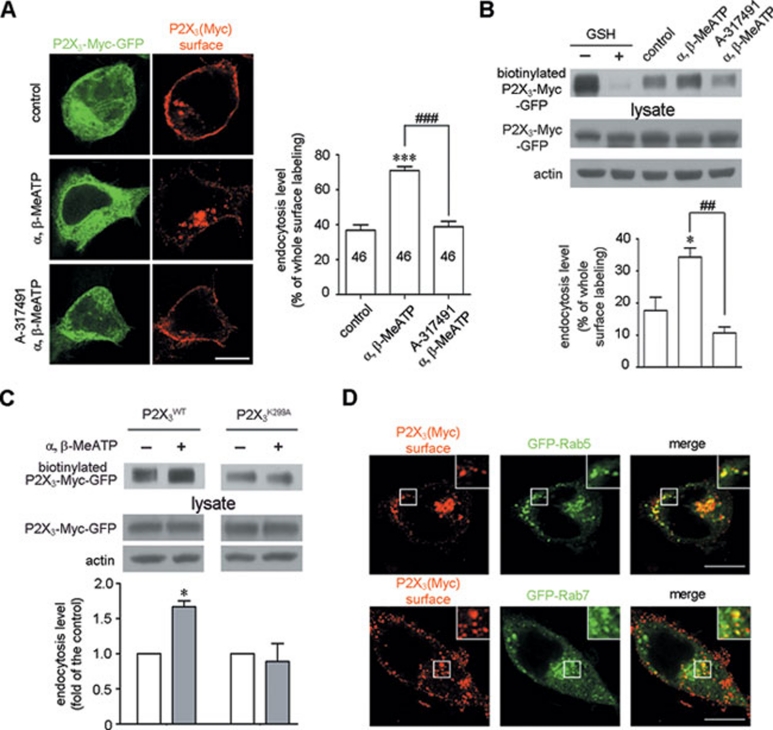

ATP-dependent endocytosis and retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors

We first examined the endocytic regulation of the P2X3 receptor by its ligand in HEK293 cells. Non-permeabilized surface labeled with an antibody against the Myc tag inserted in the extracellular loop of P2X3 receptor showed that, under basal conditions, the P2X3 receptor exhibited spontaneous endocytosis (Figure 3A). A P2X-selective agonist, α, β-MeATP, increased the number of endocytic puncta-containing P2X3 receptors, and this effect was inhibited by A-317491, a selective antagonist for the P2X3 receptor 23 (Figure 3A). We next performed a cell-surface biotinylation experiment to show that the endocytosis of P2X3-Myc-GFP was enhanced by α, β-MeATP and blocked by A-317491 (Figure 3B). The P2X3 receptor mutant in which the lysine residue at 299 is substituted with alanine (P2X3K299A-Myc-GFP) lost the ability to respond to α, β-MeATP 24 (Figure 3C). Furthermore, we found that the P2X3 receptor entered cells through the Rab5/Rab7-associated endocytic pathway. Following α, β-MeATP treatment, 43.8% ± 2.6% (n = 34 cells) and 41.3% ± 1.9% (n = 46 cells) of the P2X3 receptor-positive endocytic puncta overlapped with GFP-Rab5 and GFP-Rab7, respectively (Figure 3D). These data suggest that the activation of P2X3 receptors promotes receptor endocytosis.

Figure 3.

The endocytosis of P2X3 receptors is ligand dependent. (A) HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP were surface-labeled with a Myc antibody under non-permeabilized conditions. Representative images showed that α, β-MeATP enhanced the endocytosis of P2X3 receptors, and this effect was abolished by A-317491. Scale bar, 10 μm. The numbers on the bars represent the number of cells per condition. (B) Surface biotinylation was carried out in HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP following the same treatments as in (A). Lanes 1-2 show that surface-biotinylated P2X3-Myc-GFP was efficiently stripped with glutathione (GSH). Lanes 3-5 show that α, β-MeATP enhanced the endocytosis of P2X3 receptor, which was abolished by A-317491. Actin served as a loading control. (C) α, β-MeATP increased the endocytosis of the wild-type P2X3 receptor, but not the P2X3K299A mutant receptor. (D) Endocytic Myc-labeled P2X3 receptor-positive puncta (red) co-localized with either GFP-Rab5 or GFP-Rab7 (green) in HEK293 cells after α, β-MeATP treatment. The insets are high magnification of the areas with white square frames. Scale bar, 10 μm. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 versus control, ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 versus indicated treatment in all experiments; n = 3.

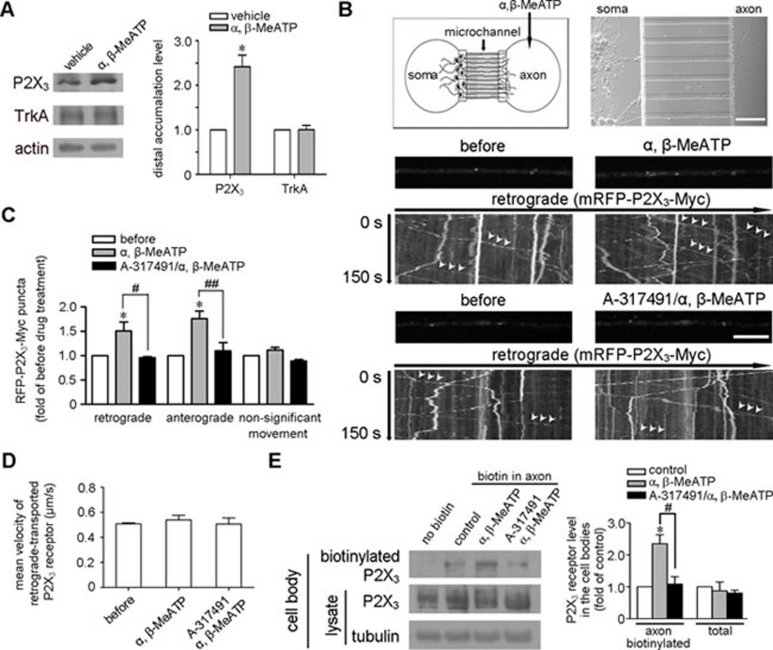

We next investigated whether the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor depends on its ligand. In vivo experiments showed that the intraplantar injection of α, β-MeATP increased the accumulation of P2X3 receptors at 24 h in the distal segment of ligated sciatic nerve compared with that in the vehicle-treated contralateral segment, but had no effect on TrkA (Figure 4A). To directly test whether the transport of P2X3 is regulated by α, β-MeATP, we used a microfluidic chamber for DRG neuron culture and live cell imaging (Figure 4B). mRFP-P2X3-Myc was expressed in DRG neurons whose axons extended through the microchannels into the axon compartment. The solution between the two compartments was not exchanged at least for 2 h, and an axon in the microchannel was observed before and after α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment. α, β-MeATP caused a 1.51 ± 0.17-fold increase in the number of retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor-positive puncta (Figure 4B and 4C). Interestingly, the number of anterogradely transported P2X3 receptor-positive puncta also exhibited a comparable 1.76 ± 0.16-fold increase. However, the mean retrograde velocity (0.54 ± 0.04 μm/s (N = 88, n = 3) for treatment versus 0.51 ± 0.01 μm/s (N = 62, n = 3) before treatment) (Figure 4D) and the number of puncta showing non-significant movement (Figure 4C) were not changed. Pre-treating with A-317491 in the axon compartment abolished the α, β-MeATP-induced changes of the numbers of retrogradely and anterogradely transported P2X3 receptor-positive puncta (Figure 4B and 4C). Consistent with this finding, the biochemical detection of the axon terminal-biotinylated proteins in the cell body compartment also showed that the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors were increased after α, β-MeATP treatment for 30 min and that A-317491 blocked this effect (Figure 4E). However, α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment had no effect on the protein level of P2X3 receptors in the cell body of DRG neurons (Figure 4E). These results suggest that ATP increases the numbers of both retrogradely and anterogradely transported P2X3 receptors.

Figure 4.

Retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors is ligand dependent. (A) Intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP following sciatic nerve ligation caused a significant increase in the number of P2X3 receptors in the distal segments of the ligated nerves but had no effect on TrkA. *P < 0.05 versus vehicle; n = 3. (B, C) A diagram of microfluidic chamber is shown (B, upper left). A differential interference contrast image of DRG neurons cultured for 5 days (B, upper right) shows that the axons crossed the microchannels into the axon compartment, while the cell bodies remained in the cell body compartment. Scale bar, 100 μm. A 2.5-min video was collected of an mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive axon in a microchannel before and after treatment in the axon compartment. The arrows indicate the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta. Quantitative data showed that α, β-MeATP increased the numbers of both retrograde and anterograde transported P2X3 receptor-positive puncta, an effect that was inhibited by A-317491, but not the number of puncta showing non-significant movement. *P < 0.05 versus that before α, β-MeATP treatment, #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 versus indicated treatment; n = 3. (D) The mean retrograde velocity was unchanged. (E) DRG neuron distal axons in the microfluidic chamber were surface-biotinylated in the axon compartment before treatments. The amount of biotinylated P2X3 receptors detected in the cell bodies of DRG neurons was increased by α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment, but not by A-317491 pre-treatment. The total level of P2X3 receptors in the cell bodies was not changed. *P < 0.05 versus control, #P < 0.05 versus indicated treatment; n = 3. Axons without biotin incubation served as a negative control. Tubulin served as a loading control.

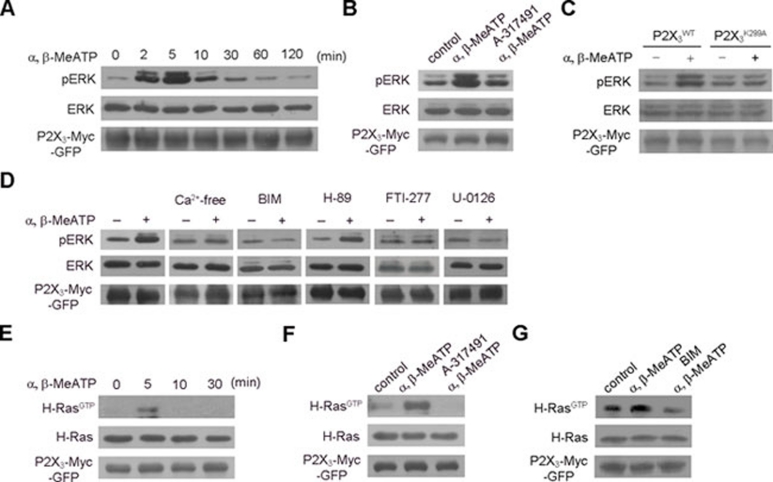

P2X3 receptor-mediated activation of a downstream signaling pathway

The P2X3 receptor is reported to activate ERK as part of the mechanical sensitivity of inflamed joints 18. In HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP, α, β-MeATP caused a relatively sustained and reversible ERK phosphorylation (pERK), with a maximum at 5 min and recovery to basal levels after 1 h (Figure 5A). Pre-treatment with A-317491 inhibited the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation (Figure 5B). The P2X3K299A-Myc-GFP mutant did not show these α, β-MeATP-mediated changes (Figure 5C). Furthermore, ERK phosphorylation was abolished when extracellular Ca2+ was absent in the medium (Figure 5D). Thus, Ca2+ influx through P2X3 receptors is required for ERK phosphorylation. We also found that depletion of extracellular Ca2+ had no effect on the α, β-MeATP-dependent endocytosis of P2X3 receptor (Supplementary information, Figure S2A and S2B), similar to the P2X4 receptor 25. Meanwhile, α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation was fully inhibited by bisindolylmaleimide I (BIM), a non-selective protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor, whereas H-89, a protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor, had no effect (Figure 5D). The Ras inhibitor FTI-277 and the MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor U-0126 also blocked the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation (Figure 5D). We used a Ras pull-down assay to detect activated Ras and found that α, β-MeATP induced Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene plasmid (H-Ras) activation in a time-dependent manner and that A-317491 abolished this effect (Figure 5E and 5F). Pre-treatment with BIM also disrupted α, β-MeATP-induced H-Ras activation, indicating that PKC is upstream of H-Ras (Figure 5G). Thus, P2X3 receptor-mediated Ca2+ influx activates a PKC-Ras-MEK-ERK pathway.

Figure 5.

ATP-induced Ca2+ influx through P2X3 receptors activates downstream signaling molecules. (A) Representative blots showed a time-dependent ERK phosphorylation (pERK) in HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP by α, β-MeATP. Total ERK served as a loading control. (B) α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation was inhibited by A-317491. (C) α, β-MeATP failed to induce ERK phosphorylation in HEK293 cells expressing P2X3K299A-Myc-GFP. (D) This ERK phosphorylation was also abolished by extracellular Ca2+ depletion (Ca2+-free) or BIM, FTI-277 or U-0126, but not H-89. (E, F) Representative blots showed a time-dependent H-Ras activation in HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP by α, β-MeATP that was abolished by A-317491. Total H-Ras served as a loading control. (G) BIM pre-treatment also abolished the α, β-MeATP-induced H-Ras activation.

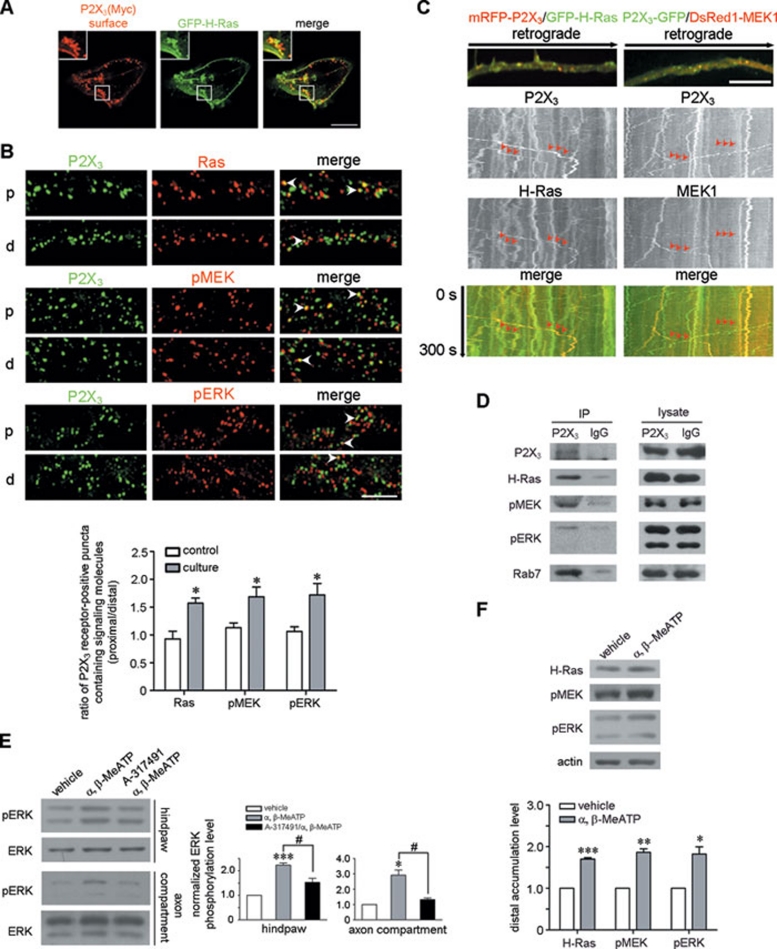

Retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors associate with activated signaling molecules

We next investigated the relationship of subcellular distribution between endocytic P2X3 receptor and signaling molecules. Non-permeabilized surface labeling in HEK293 cells expressing RFP-P2X3-Myc showed that 60.1% ± 2.1% (n = 45 cells) of the α, β-MeATP-induced endocytic P2X3 receptor-positive puncta contained GFP-tagged H-Ras (GFP-H-Ras) (Figure 6A). We then tested whether the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors associated with the signaling molecules in axons. In sciatic nerves cultured for 10 h, the ratio of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta co-localized with signaling molecules in the proximal versus distal part was significantly increased compared with the control nerves (1.57 ± 0.09 (Nproximal = 1 403, Ndistal = 1 307) versus 0.93 ± 0.14 (Nproximal = 440, Ndistal = 609) for Ras; 1.69 ± 0.17 (Nproximal = 1 646, Ndistal = 1 598) versus 1.13 ± 0.09 (Nproximal = 934, Ndistal = 891) for phospho-MEK (pMEK); 1.72 ± 0.20 (Nproximal = 1 281, Ndistal = 1 369) versus 1.06 ± 0.08 (Nproximal = 389, Ndistal = 1 728) for phospho-ERK (pERK); n = 3) (Figure 6B). We then performed live cell imaging in cultured DRG neuron axons and found that 27.6% ± 5.4% of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta (N = 386, n = 3) associated with the same carriers as GFP-H-Ras and 40.2% ± 5.6% of P2X3-Myc-GFP-positive puncta (N = 425, n = 3) with DsRed1-tagged MEK 1 (DsRed1-MEK1) during long-distance retrograde movement (Figure 6C; Supplementary information, Movie S7 and S8). Organelle immunoisolation from sciatic nerve axoplasm showed that H-Ras, pMEK, pERK and Rab7 were co-localized in P2X3 receptor-containing vesicles (Figure 6D). Intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP for 5 min activated ERK in the hindpaw (Figure 6E). Treatment with α, β-MeATP in the axon compartment of a microfluidic chamber for 5 min also activated ERK in the distal axons of DRG neurons (Figure 6E). Both activations could be inhibited by A-317491 (Figure 6E). Furthermore, intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP for 24 h increased the accumulation of H-Ras, pMEK and pERK in the distal segment of ligated sciatic nerve compared with that in the vehicle-treated contralateral segment (Figure 6F), synchronizing the promoted retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors (Figure 4A). These data suggest that the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors may associate with activated signaling molecules.

Figure 6.

P2X3 receptors couple to signaling molecules in the retrograde transport route. (A) Endocytic Myc-labeled P2X3 receptor-positive puncta (red) co-localized with GFP-H-Ras in HEK293 cells after α, β-MeATP treatment. Scale bar, 10 μm. The insets show the high magnification of the areas within the white square frames. (B) Representative images illustrated that Ras, pMEK, and pERK co-localized with P2X3 receptors (arrows) in the proximal (p) and distal (d) segments of cultured sciatic nerves. The retrogradely transported ratios calculated from the percentages of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta containing H-Ras, pMEK or pERK in the proximal versus distal segments showed a significant increase compared with those in freshly collected nerves. *P < 0.05; n = 3. Scale bar, 10 μm. (C) Live cell imaging shows that GFP-H-Ras or DsRed1-MEK1 was co-transported with P2X3 receptors along the retrograde route (arrows) in the axons of cultured DRG neurons. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) The organelle immuno-isolated with a P2X3 receptor from sciatic nerve axoplasm contained H-Ras, pMEK, pERK and Rab7. (E) α, β-MeATP application in the hindpaw and axon compartment activated ERK in nerve terminals. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle, #P < 0.05 versus indicated treatment; n = 3–4. (F) As shown in Figure 4A, intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP caused a significant increase in the levels of H-Ras, pMEK and pERK in the distal segment of the ligated sciatic nerve. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle; n = 4.

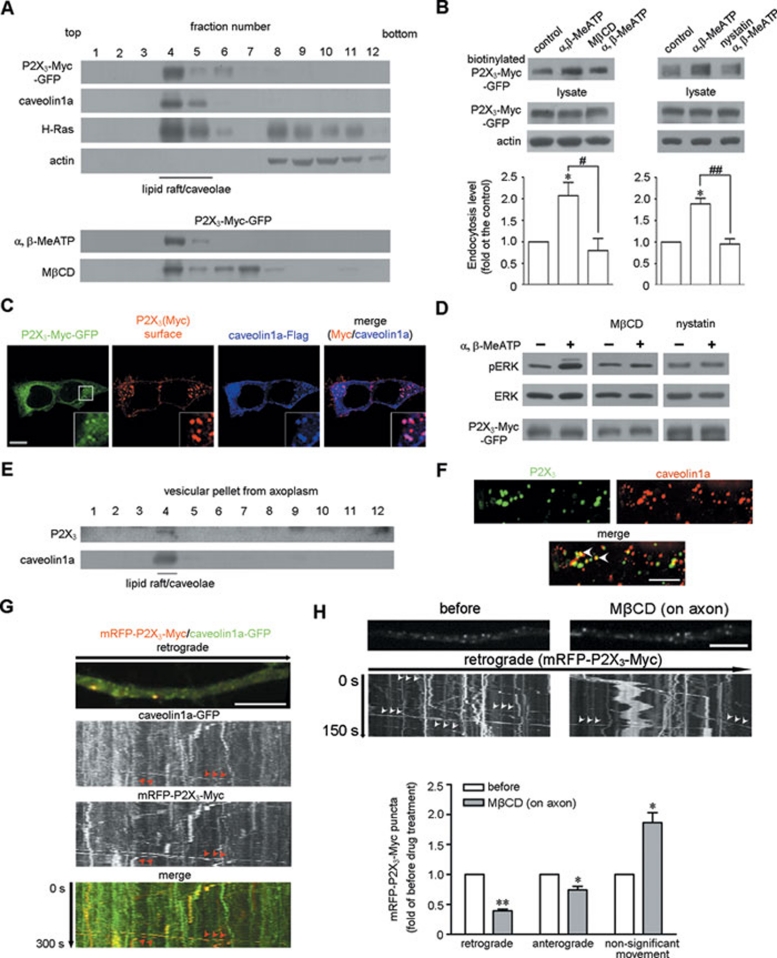

Lipid rafts may mediate the assembly of P2X3 receptor-containing signaling endosomes

How does the activation of P2X3 receptor couple to receptor endocytosis and its downstream signaling molecules? Lipid rafts are a specialized membrane microdomain 26 and participate in many signal transduction events 27, 28. The P2X3 receptor is localized in the lipid rafts of DRG neurons 29. We thus investigated the role of lipid rafts in α, β-MeATP-dependent endocytosis and signal transduction in HEK293 cells. Composition fractionation with a discontinuous sucrose gradient showed that P2X3-Myc-GFP and the downstream H-Ras 30 was abundantly distributed in fractions labeled by the lipid raft marker caveolin1a, and this pattern was not affected by α, β-MeATP (Figure 7A), similar to previous reports 29, 31. The application of cholesterol-depleting agent methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), which was reported to have no effect on membrane integrity 32, caused the P2X3 receptors to redistribute into non-lipid raft fractions (Figure 7A). The cell-surface biotinylation experiment showed that the α, β-MeATP-induced endocytosis of P2X3 receptors was inhibited by both MβCD and the cholesterol sequestration agent nystatin (Figure 7B). Non-permeabilized surface labeling of the P2X3 receptor showed that 69.6% ± 1.9% (n = 47 cells) of the endocytic P2X3 receptor-positive puncta overlapped with Flag-tagged caveolin1a (caveolin1a-Flag) after α, β-MeATP treatment in HEK293 cells (Figure 7C). MβCD and nystatin also blocked the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation (Figure 7D). Taken together, these data suggest that the lipid raft is the microdomain through which P2X3 receptor endocytosis and activation of the downstream MAPK/ERK pathway are mediated.

Figure 7.

Lipid rafts mediate the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation, endocytosis and retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors. (A) P2X3-Myc-GFP and H-Ras were co-fractionated in lipid raft fractions marked by caveolin1a in HEK293 cells. Actin was present in non-lipid raft fractions. MβCD pre-treatment, but not α, β-MeATP treatment, shifted a large portion of P2X3-Myc-GFP into the non-lipid raft fractions. (B) Both MβCD and nystatin abolished the α, β-MeATP-induced endocytosis of P2X3-Myc-GFP in HEK293 cells. *P < 0.05 versus control, #P < 0.05 and ##P < 0.01 versus indicated treatment; n = 3–4. (C) Endocytic Myc-labeled P2X3 receptor-positive puncta (red) co-localized with caveolin1a-Flag (blue) in HEK293 cells after α, β-MeATP treatment. The insets show the high magnification of the areas within the white square frame. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Both MβCD and nystatin abolished the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation. Total ERK served as a loading control. (E) Vesicular P2X3 receptors in the axoplasm of sciatic nerves were co-fractionated with caveolin1a in the lipid raft fraction. (F) Caveolin1a co-localized with P2X3 receptors in sciatic nerves. Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Live cell imaging showed that mRFP-P2X3-Myc (arrows) was co-transported with caveolin1a-GFP (arrows) in the retrograde direction in cultured DRG neuron axons. (H) The arrows indicate the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors-positive puncta in the cultured DRG neuron axons of the microfluidic chamber. The amount of retrogradely transported mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta was attenuated by the application of MβCD into the axon compartment. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 versus that before treatment; n = 3. Scale bar, 5 μm.

To detect P2X3 receptor distribution in DRG neuron axons, a sucrose-gradient fractionation with vesicular pellets prepared from sciatic nerve axoplasm showed that vesicular P2X3 receptors were abundantly distributed in lipid raft fractions (Figure 7E). Furthermore, 37.1% ± 3.2% of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta (N = 848, n = 3) in the sciatic nerve contained caveolin1a (Figure 7F). Live cell imaging showed that mRFP-P2X3-Myc could utilize the same carrier as GFP-tagged caveolin1a (caveolin1a-GFP) in the retrograde transport route (Figure 7G). MβCD treatment in the axon compartment of microfluidic chamber disrupted the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors in the cultured DRG neuron axons (Figure 7H). Thus, lipid rafts mediate the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor in the axons.

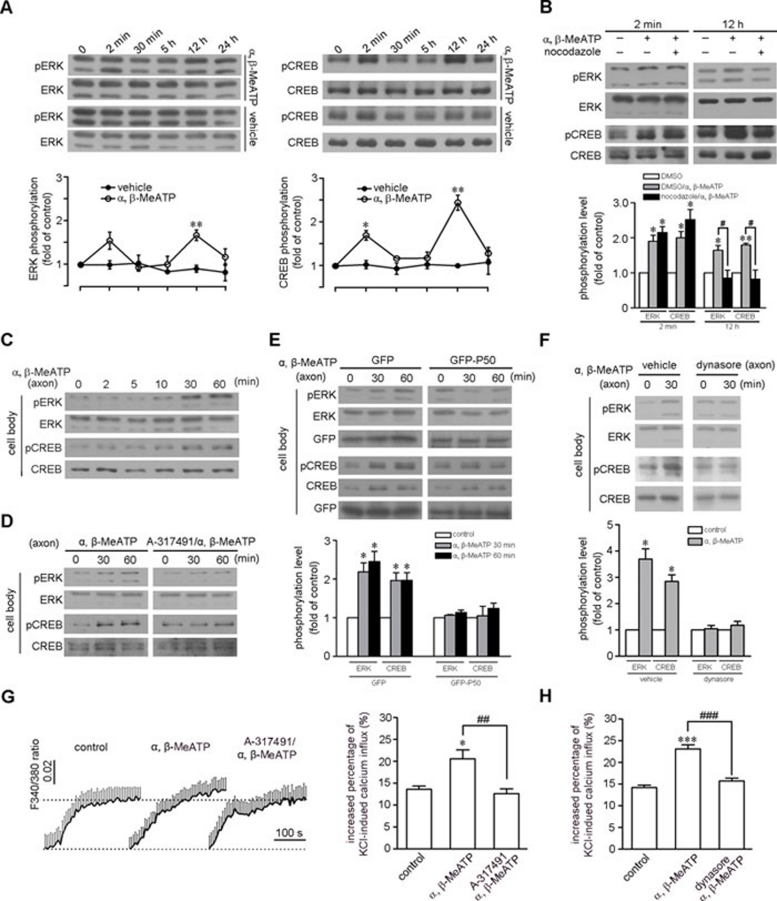

Activation of the transcription factor CREB and an increase in neuronal excitability by retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor signals

CREB is one of the most important transcription factors downstream of the Ras-MEK-ERK signaling pathway and is involved in the regulation of many genes related to cell survival and proliferation 33. We explored the effect of retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor signals in DRG neurons. Immunoblots showed that the intraplantar injection of α, β-MeATP enhanced the level of pERK and phospho-CREB (pCREB) synchronously in DRG neurons in a time-dependent manner (Figure 8A). The short-term effect appeared around 2 min after α, β-MeATP injection in the ipsilateral DRG neurons and may represent an effect of Ca2+ entry and action potential propagation following the activation of P2X3 or P2X2/P2X3 receptors, which is consistent with a previous report 17. The long-term effect occurred at approximately 12 h and diminished at approximately 24 h (Figure 8A), which coincided with the velocity of the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors calculated from our experiments in cultured DRG-sciatic nerves. In microfluidic cultured DRG neurons, the significant elevation of pERK and pCREB appeared at 30 min and persisted for 1 h in the cell body compartment following α, β-MeATP application to axon compartment (Figure 8C). Pre-treatment with A-317491 in the axon compartment abolished this elevation of pERK and pCREB (Figure 8D). In contrast, α, β-MeATP treatment applied directly to the cell body of cultured DRG neurons activated ERK and CREB within 5 min (Supplementary information, Figure S3). Thus, ATP and the P2X3 receptor system in axon terminals increase the phosphorylation level of ERK and CREB in the cell bodies of DRG neurons.

Figure 8.

Activation of ERK/CREB and an increase in neuronal excitability via retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor signals. (A, B) Intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP synchronously induced two phases of activation of ERK and CREB in L4-L5 DRG neurons with a short-term effect around 2 min and a long-term effect around 12 h. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus corresponding vehicle treatment; n = 4 (A). The activation of ERK and CREB at 12 h, but not 2 min, was abolished by the injection of nocodazole into the sciatic nerve before intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus a DMSO injection into the sciatic nerve, #P < 0.05 versus indicated treatment; n = 3 (B). (C, D) The ERK and CREB phosphorylation level in the cell bodies of cultured DRG neurons in the microfluidic chamber was elevated after α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment for 30 min and 60 min. This effect was abolished by A-317491. Total ERK and CREB served as loading controls. (E) α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment induced elevations in pERK and pCREB at 30 min and 60 min in the cell bodies of GFP-transfected neurons in the microfluidic chamber. This effect was abolished by the overexpression of GFP-P50. *P < 0.05 versus control; n = 3. Total ERK and CREB served as loading controls. (F) The elevation of pERK and pCREB in the cell bodies of DRG neurons induced by α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment for 30 min was disrupted by dynasore. *P < 0.05 versus control; n = 3. (G) α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment for 30 min increased the depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies of DRG neurons. *P < 0.05 versus control, ##P < 0.01 versus indicated treatment; n = 3. (H) Dynasore pre-treatment in the axon compartment of the microfluidic chamber inhibited the increase of high K+-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies of DRG neurons induced by α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment for 30 min. ***P < 0.001 and ###P < 0.001 versus indicated treatment; n = 3.

We further addressed whether the elevation of pERK and pCREB in the cell bodies of DRG neurons depended on the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor-activated signaling. Injection of sciatic nerves with the microtubule depolymerizing drug nocodazole abolished the increase in pERK and pCREB induced by the intraplantar injection of α, β-MeATP around 12 h, but had no effect on the increase that occurred around 2 min in the cell bodies of DRG neurons (Figure 8B), indicating that the long-term effect depends on the microtubule-based axon transport of signals. Retrograde transport is primarily mediated by the dynein-dynactin complex 34. We found that in sciatic nerves, 45.8% ± 14.0% (N = 1 785, n = 3) of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta were labeled with the dynein intermediate chain (DIC). In sciatic nerves cultured for 10 h, the ratio of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta containing DIC in the proximal versus distal part was significantly increased compared to control nerves (2.07 ± 0.22 (Nproximal = 815, Ndistal = 1 209) versus 1.10 ± 0.08 (Nproximal = 544, Ndistal = 1 241), n = 3) (Supplementary information, Figure S4A). P50-dynamitin is one subunit of the dynactin complex. Overexpression of P50 leads to the dissociation of the dynactin complex and disrupts dynein function 35. In the axons of DRG neurons co-expressing mRFP-P2X3-Myc and GFP-tagged P50 (GFP-P50), only 11.1% ± 7.6% of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta displayed retrograde transport, while 71.3% ± 7.6% of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta showed non-significant movement (N = 471, n = 3), compared with 55.6% ± 5.0% and 28.9% ± 1.5%, respectively, in neurons expressing mRFP-P2X3-Myc and GFP (N = 363, n = 3). The anterograde transport of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta was not altered by P50 (16.8% ± 6.1% versus 15.4% ± 1.5%) (Supplementary information, Figure S4B). Importantly, in GFP-P50-expressing DRG neurons, α, β-MeATP no longer elevated pERK and pCREB in the cell bodies following treatment of the axon compartment for 30 min or 1 h (Figure 8E). Thus, the retrograde axonal transport is important for P2X3 receptor-activated signaling.

We also examined the influence of endocytosis on the retrograde axonal transport of P2X3 receptor signals. Lipid raft-dependent endocytosis can be regulated by dynamin 36. Immunoblots showed that a 30-min pre-treatment with 80 μM dynasore, a cell-permeable dynamin inhibitor 37, abolished the α, β-MeATP-induced endocytosis of P2X3 receptors without any obvious effect on the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation via P2X3 receptors in HEK293 cells (Supplementary information, Figure S5A and S5B). This finding indicates that ATP-induced pERK is independent of the endocytosis of P2X3 receptors. Furthermore, dynasore pre-treatment in the axon compartment of the microfluidic chamber abolished the elevation of pERK/pCREB in the cell body compartment induced by the application of α, β-MeATP to the axon compartment for 30 min (Figure 8F); however, the α, β-MeATP-induced ERK phosphorylation in axon terminals was not affected (Supplementary information, Figure S5C). Thus, the long-distance retrograde signaling of P2X3 receptors depends on the ATP-activated receptor endocytosis.

Finally, we measured neuronal excitability by examining the high K+-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies of cultured DRG neurons in a microfluidic chamber using Ca2+ imaging. Compared to control cells (n = 41 cells), α, β-MeATP (n = 54 cells) applied to the axon compartment for 30 min increased the high K+-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies, and this increase was inhibited by A-317491 (n = 33 cells) (Figure 8G). Dynasore pre-treatment in the axon compartment of the microfluidic chamber also inhibited the α, β-MeATP-induced increase in the high K+-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies of DRG neurons (n = 54, 53 and 62 cells for control, α, β-MeATP and α, β-MeATP plus dynasore, respectively; Figure 8H). Taken together, these data indicate that the ATP-induced retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor-containing signaling endosomes activates the ERK/CREB pathway and may increase the excitability of DRG neurons.

Discussion

The P2X3 receptor is an ATP-gated ion channel and is involved in pain transduction. In the present study, we provide both in vitro and in vivo evidence for the presence of ATP-induced retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor signals in DRG neuron axons. Our results from ligated and cultured sciatic nerve experiments showed an accumulation of P2X3 receptors in the retrograde direction. Live cell imaging confirmed the retrograde movement of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta, which displayed characteristics of fast axonal transport. Furthermore, we found that ATP activates a PKC-Ras-MEK-ERK signaling pathway to form P2X3 receptor-containing signaling endosomes that move retrogradely to increase the activation level of the transcription factor CREB and neuronal excitability in the cell bodies of DRG neurons. The discovery of the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor signaling provides a novel mechanism by which ligand-gated ion channels, such as ATP receptors, function in neurons.

Ligand-dependent and endosome-mediated retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors

ATP has long been recognized as an intracellular energy source and has been proposed as a neurotransmitter 38, 39. There is clear evidence for multiple pathways of ATP release from normal cells 10, especially dying cells and damaged tissues 40, 41. It is well accepted that ATP and the P2X3 receptor play an important role in pain transmission 42, 43. In addition to their effects at neuronal terminals, we showed here that the P2X3 receptor is retrogradely transported at speeds within the range of dynein-mediated transport 1 in DRG neuron axons using sciatic nerve ligation, sciatic nerve culture and live cell imaging. Retrograde axonal transport is an accepted process for moving proteins from the axon back to the cell body for lysosomal degradation. However, consistent with the P2X3 receptors in DRG neurons, the molecular weight of these receptors from the distal segment of ligated sciatic nerves and the axon terminal-biotinylated proteins in the cell body compartment was ∼53 kD. This result suggests that the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors are not simply targeted for degradation in DRG neurons.

Is the retrograde transport of the P2X3 receptor regulated by its ligand? In HEK293 cells, the P2X receptor agonist α, β-MeATP enhanced the endocytosis of P2X3 receptors, and this effect was inhibited by the P2X3 receptor selective antagonist A-317491. In the microfluidic culture of DRG neurons, the axon terminal-biotinylated P2X3 receptors detected in the cell body compartment were increased by α, β-MeATP, and A-317491 pre-treatment in the axon compartment blocked this effect. Thus, the endocytosis of the P2X3 receptor is regulated by its ligand. Moreover, the intraplantar injection of α, β-MeATP enhanced the accumulation of P2X3 receptors in the distal segment of ligated sciatic nerve. This phenomenon resulted from the increased endocytosis of P2X3 receptors at the nerve terminal because α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment increased only the number, not the velocity, of retrogradely transported P2X3 receptor-positive puncta in cultured DRG neurons. Thus, the activation, endocytosis and ensuing fast retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors depend on ATP.

Interestingly, we found that the treatment of peripheral axons with α, β-MeATP increased the number of anterogradely transported P2X3 receptor-positive puncta to a comparable degree. ATP applied in axons had no effect on the protein level of P2X3 receptors in the cell body of DRG neurons. This regulated transport of P2X3 receptors may represent a mechanism to compensate for the loss of receptors induced by ligand stimulation at peripheral terminals. One possible explanation is that a dynamic pool of P2X3 receptors might exist in axons for delivery to nerve terminals, followed by ATP-activated endocytosis. Indeed, local treatment on distal axons with NGF enhanced the anterograde TrkA delivery and exocytosis into axon growth cones 44. We speculate that ATP-initiated anterograde transport of P2X3 receptors might be used for increasing nociceptive responses and may be involved in the hypersensitization of sensory neurons.

NGF signals appear to be carried by both Rab5-containing early endosomes 6, 45 and Rab7-containing late endosomes 46, while tetanus neurotoxin (TeNT HC) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)/tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) are retrogradely transported by late endosomes 47. We used live cell imaging to show that ∼55% of puncta co-expressing the P2X3 receptor and Rab7 moved retrogradely at a fast transport speed, compared to ∼30% of puncta co-expressing the P2X3 receptor and Rab5, which traveled at a much slower average velocity. A dominant-negative Rab7 mutant (Rab7T22N) resulted in a significant inhibition of movement for ∼80% of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta. Taken together, our data suggest that Rab7-endosomes are the primary carriers for the long-distance retrograde transport of the P2X3 receptor. Nevertheless, Rab5-endosomes appear to be required during a step that precedes the long-distance axonal transport, as proposed by Deinhardt et al. 47, given that a dominant-negative Rab5 mutant (Rab5S34N) also inhibited the movement of ∼60% of P2X3 receptor-positive puncta. P2X3 receptor-positive puncta containing GFP-Rab5WT displayed low mobility and should belong to the slowly maturing early endosome, as previously reported 48.

The P2X3 receptor-activated signaling pathway and signaling endosomes

Activation of P2X1 and P2X7 receptors could activate signaling molecules, including ERK 49, 50. Our results revealed that P2X3 receptor signaling was mediated by a PKC-Ras-MEK-ERK pathway, similar to that of the P2X1 receptor 49. Ca2+ influx through the P2X3 receptor was necessary for the activation of this signaling pathway, as neither the P2X3 receptor mutant (P2X3K299A) nor α, β-MeATP treatment in a Ca2+-free medium was able to induce ERK phosphorylation. However, the endocytosis of P2X3 receptors was not required for inducing signal transduction, as the disruption of dynamin-dependent endocytosis with dynosore blocked the α, β-MeATP-induced endocytosis of P2X3 receptor, but had no effect on ERK phosphorylation.

Usually, receptors and ion channels in neurons are activated at the nerve terminal. Signaling endosomes have been demonstrated to transmit neurotrophin signals across long distances to the cell body 45, 51, 52. Here, we propose that the P2X3 receptor, a ligand-gated ion channel, may adopt retrograde signaling endosomes to transmit its downstream signals. In our experiments, Ras, pMEK and pERK were detected in the vesicles immuno-isolated with a P2X3 receptor antibody from sciatic nerve axoplasm. Additionally, these signaling molecules co-localized with the P2X3 receptor and were found to accumulate in cultured sciatic nerve segments in a retrogradely transported direction. Live cell imaging showed that Ras and MEK1 could share carriers with the P2X3 receptor, which are primarily mediated by Rab7-endosomes during long-distance retrograde movement in cultured DRG neurons. Furthermore, intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP increased the accumulation of Ras, pMEK and pERK with P2X3 receptors in the distal segment of ligated sciatic nerve and elevated the pERK level in cell bodies of DRG neurons. In microfluidic-cultured DRG neurons, α, β-MeATP treatment of the axons also elevated the level of pERK in cell bodies at 30 min, and this increase lasted more than 1 h. Disruption of microtubule-based axonal transport with nocodazole in vivo or dynein function with P50 overexpression in vitro blocked the retrograde transport of pERK. Taken together, these results suggest that P2X3 receptors may transmit signals via retrograde signaling endosomes.

How is the activation of P2X3 receptors coupled with activated signaling molecules? Recent studies suggest that P2X receptor members, including P2X3 29, 31, P2X1, P2X2, P2X4 and P2X7 31, 53, 54, localize in lipid rafts. We also found that P2X3 receptors were concentrated in caveolin1a-marked lipid rafts in HEK293 cells and the axoplasm of sciatic nerves. Lipid rafts are proposed to be a signaling platform for efficient signal transduction 27, 28. In our study, disruption of the lipid raft with MβCD or nystatin abolished ligand-induced P2X3 receptor endocytosis and retrograde transport, and ERK phosphorylation. These results suggest that lipid rafts are essential for the assembly of P2X3 receptor-containing signaling endosomes. This hypothesis is further supported by the finding that H-Ras, preferentially localized in lipid rafts for selective signaling pathways 30, is localized in lipid rafts together with the P2X3 receptor.

Two additional critical questions are whether the P2X3 receptor just rides in the endosome to be degraded at the cell body or is part of the retrogradely transported signals and how the P2X3 receptor-activated signaling event is maintained in the endosomes en route to the cell body. The selective antagonist A-317491 is not easily permeabilized into cells due to the three carboxyl groups in its structure. Thus, we were unable to test the necessity of P2X3 receptor activation in the signaling endosomes for retrograde signaling. A cell-permeable selective antagonist of the P2X3 receptor should be developed to solve this issue. Because ATP is very stable in acidic late endosomes and lysosomes 55, it is possible that ATP within these organelles could constantly activate P2X3 receptors to maintain the signals during the long-distance retrograde transport process. Additionally, some adaptor proteins may associate with the P2X3 receptor-activated signaling molecules in the signaling endosomes to prevent their inactivation, as suggested by Perlson et al. 56.

Function of the P2X3 receptor retrograde signals

The retrograde transport of NGF-TrkA signals is believed to activate transcription factors and initiate gene transcription in the cell body 5, 57. We found a similar effect for the ATP-P2X3 receptor retrograde signals. The intraplantar injection of α, β-MeATP enhanced the pCREB level in DRG neurons in a time-dependent manner. The long-term effect observed at approximately 12 h after α, β-MeATP injection should be attributed to the long-distance physical retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor-containing signaling endosomes. In microfluidic-cultured DRG neurons, a significant activation of CREB was detected at 30 min and persisted at least 1 h following the axonal application of α, β-MeATP. These results suggest an endosome-based signaling via a long-distance movement in the axon, given that α, β-MeATP treatment applied directly to the cell body of cultured DRG neurons activated CREB within 5 min. Furthermore, the injection of sciatic nerves with nocodazole, the overexpression of P50-dynamitin and the application of dynasore to the axon terminal all inhibited the CREB activation in the cell body induced by α, β-MeATP application at the nerve terminals.

Previous reports have suggested that inflammatory and neuropathic pain increases pERK in DRG neurons and that activation of the ERK pathway is involved in peripheral sensitization following noxious stimulation 58, 59, 60. In our experiment, α, β-MeATP applied to the axon terminal for 30 min was able to increase the level of pERK as well as the depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies. This effect was inhibited by the application of a P2X3 receptor antagonist or endocytosis inhibitor to the axon terminal. Dynasore treatment did not affect the activation of P2X3 receptors or the transduction of action potentials in axons. Thus, the increase in depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx in the cell bodies of DRG neurons induced by α, β-MeATP treatment in the axon compartment for 30 min resulted from ATP-dependent endocytosis and the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptor signals. This result represents an acute and long-lasting modulation of neuronal excitability. Both protein phosphorylation and gene expression regulation may contribute to this phenomenon. The CREB activation by retrogradely transported neurotrophin signals activates the transcription of multiple genes, and induces and maintains neurite growth 5. Our microarray results (unpublished data) showed that intraplantar injection with α, β-MeATP regulated the expression of many genes in DRG neurons after 12 h. Furthermore, it is well known that peripheral inflammation and nerve injury increase ATP release. Thus, the endosome-mediated retrograde axonal transport of P2X3 receptor signals described here is hypothesized to be involved in the inflammation and injury-induced neuronal hypersensitivity.

In summary, our discovery that ion channel receptors form signaling endosomes to convey retrograde signals in neurons represents a significant advance towards understanding the cellular mechanisms by which these receptors signal and function. We conclude that P2X3 receptor-associated signaling molecules, through long-distance retrograde transport, increase the activation level of CREB and other molecules in the cell body to maintain neuronal activity and excitability. Importantly, CREB activation in cell body by P2X3 receptor-activated retrograde signaling may contribute to the long-lasting nociceptive sensitivity associated with chronic inflammation 61.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids and antibodies

The P2X3-Myc-GFP plasmid with a Myc tag in the extracellular loop and a GFP tag at the C-terminus was provided by F Rassendren (University of Sheffield, UK). mRFP-P2X3-Myc was sub-cloned from P2X3-Myc-GFP. P2X3K299A-Myc-GFP was mutated from P2X3-Myc-GFP using a KOD site-mutagenesis kit (Toyobo). Caveolin1a-Flag and caveolin1a-GFP were cloned from the rat uterus cDNA library. GFP-H-Ras was kindly provided by Prof Y Chen (Institute of Nutritional Science, CAS, China). DsRed1-MEK1 was provided by Dr H Bading (University of Heidelberg, Germany). GFP-P50 was a gift from Prof X Zhu (Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, CAS, China). GFP-Rab5WT, GFP-Rab5S34N and GFP-Rab7WT were obtained from Dr P Wang (East China Normal University, China). GFP-Rab7T22N was mutated from GFP-Rab7WT. For antibody information, please see the Supplementary information, Table S1.

Animal models of sciatic nerve ligation and ATP injection

All animal experiments were carried out according to a protocol approved by the Committee of Use of Laboratory Animals and Common facility of the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Under anesthesia, the sciatic nerves of male Sprague-Dawley rats (body weight ∼250 g; Shanghai Center of Experimental Animals, Chinese Academy of Sciences) were ligated unilaterally with a 5-0 silk suture and two ligatures, spaced 1 mm apart, at the middle thigh level. The contralateral sciatic nerve was exposed as a sham-operated control. After one day, equal lengths of the proximal and distal ligation segments from the ipsilateral and contralateral sciatic nerves were freshly dissected for western blotting to probe the levels of the P2X3 receptor, TrkA, NGF and synaptophysin. For immunohistochemistry, the rat was deeply anesthetized, and the heart was perfused with 50 ml warm (37 °C) saline followed by a warm mixture of 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), followed by the ice-cold application of the same fixative for 5 min. The nerve was dissected and then post-fixed in the same fixative for 90 min at 4 °C and in 20% sucrose in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 24 h prior to being sectioned at 10 μm for immunostaining.

For detection of ATP-dependent receptor retrograde transport, 100 nmol α, β-MeATP diluted in 100 μl PBS 62 was injected subcutaneously into the hindpaw immediately after sciatic nerve ligation. As a control, an equal volume of PBS was injected into the contralateral side following sciatic nerve ligation. Twenty-four hours after injection, equal lengths of the distal segments to ligation were dissected for western blotting to probe the levels of the P2X3 receptor, TrkA, H-Ras, pMEK and pERK. To detect local ERK activation, α, β-MeATP, α, β-MeATP/A-317491 or vehicle was injected into the hindfoot pad for 5 min prior to footpad homogenization. To test for the activation of signaling molecules in vivo, α, β-MeATP was injected into the hindfoot pad for different durations prior to the homogenization of the ipsilateral lumbar (L)4 and L5 DRG neurons for western blotting to investigate pERK, ERK, pCREB and CREB expression. The contralateral side was injected with PBS as a control. In the case of nocodazole treatment, 2.5 μl nocodazole (10 mg/ml, Sigma) was injected into the sciatic nerve with a Hamilton syringe prior to the intraplantar injection of α, β-MeATP.

PNGase F treatment

Adult rat DRG neurons were homogenized in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin; pH 7.4) followed by incubation with 0.5 μl PNGase F (5 000 units/ml; Sigma) at 37 °C for 5 h to deglycosylate proteins. The protein samples were then processed for western blotting and immunoblotted using an antibody against the P2X3 receptor.

Sciatic nerve and DRG-sciatic nerve culture

The chambers for sciatic nerve and DRG-sciatic nerve culture were modified according to previous reports 6, 21. Briefly, 4–4.5 cm sciatic nerve segments from ∼300 g rats were placed on the top of a 1% agarose gel bed in a 96-microwell plate. The nerve ends were submerged with oxygenated Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; GIBCO) supplemented with 2% B27, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM PMSF and 1 mM NaF. After a 10-h culture, the axoplasm of equal length segments was extracted using the blunt end of a razor blade and collected in PBS containing protease inhibitors for western blotting. Freshly collected sciatic nerves were processed for controls. For immunohistochemistry, proximal and distal 0.5 cm ends of the cultured sciatic nerves were cut open with Vannas scissors, and the axons were exposed with two fine pinheads, fixed with cold methanol and then hydrated with PBS and processed for immunostaining, as described below.

For the DRG-sciatic nerve culture, L4-L5 DRG neurons linked with 3 cm sciatic nerves were dissected. The sciatic nerves were placed on the gel bed with DRG neurons, and the nerve ends were submerged in the collection buffer. The distal nerve end was incubated with an antibody against the C-terminus of the P2X3 receptor or a control IgG in DMEM with B27 for 0, 3, 6, 9 or 12 h. The DRG neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C, cryoprotected in 20% sucrose, and then cut on a cryostat into 10-μm sections for immunostaining.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (GIBCO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. Transient expression was performed with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's protocol. One and a half days after transfection, cells were serum-starved for at least 12 h prior to the experiments.

Dissociated DRG neurons from ∼100 g rats were transfected by electroporation with Nucleofector II (Amaxa) using a rat neuron nucleofection kit and then plated in DMEM containing 10% FBS. After 6 h, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM/F12 (1:1) containing 1% N2 supplement, and the neurons were maintained for 48 h for further experiments. For compartment culture, the microfluidic chamber was fabricated, and dissociated DRG neurons were plated in the cell body compartment of the microfluidic chamber. Axons crossed the microchannels and reached the axon compartment within 3-5 days.

Drug treatment of cultured cells

HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP were serum starved for 12 h and treated with 1 μM α, β-MeATP (Sigma) or α, β-MeATP and 10 μM A-317491 (Sigma), as indicated. For the antagonist blockage experiment, cells were pre-treated with 10 μM A-317491 for 1 h. To define the pathway leading to ERK activation, cells were pre-treated with 5 μM of the PKC inhibitor BIM (Calbiochem), 10 μM of the PKA inhibitor H-89 (Sigma), 10 μM of the Ras farnesylation inhibitor FTI-277 (Sigma) and 10 μM of the MEK inhibitor U-0126 (Sigma) for 30 min and then treated with 1 μM α, β-MeATP for 5 min. In the case of extracellular Ca2+-free condition, the cells were incubated in Ca2+-free DMEM with 1 μM EGTA for 5 min and then treated with α, β-MeATP in the same medium. To disrupt the lipid rafts, 15 mg/ml MβCD (Sigma) or 25 μg/ml nystatin (Sigma) were added for 45 min prior to α, β-MeATP treatment. To inhibit dynamin-dependent endocytosis, cells and axons were pre-treated with 80 μM dynasore (Sigma) for 30 min.

Live cell imaging

The electroporated DRG neurons cultured on glass bottom dishes were placed on a temperature-controlled workstation (37 °C) with an inverted microscope and imaged with the PerkinElmer UltraView Vox system (PerkinElmer Inc.) using a 100× oil lens (numerical aperture 1.49), the Leica TCS SP5 II system (Leica) using a 63× oil lens (numerical aperture 1.32) or the Nikon A1R inverted confocal system (Nikon) using a 60× oil lens (numerical aperture 1.40). Regions of the axon segments were selected randomly, and 150 frames were collected for a 5-min period.

To image the transport of P2X3 receptors during drug treatment, an axon expressing mRFP-P2X3-Myc and extending to the axon compartment in a microchannel of the microfluidic chamber was selected for time-lapse imaging. A 2.5-min video was acquired before and after treatment with 1 μM α, β-MeATP or α, β-MeATP/10 μM A-317491 in the axon compartment for 10 min. The kymograph was generated using ImageJ 1.4 software (NIH). The analysis of the puncta population, total number, average velocity and active velocity in a particular kymograph was performed using Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software (Media Cybernetics Inc.). The data were acquired from at least three independent experiments.

Fabrication of microfluidic devices

The microfluidic chamber fabricated for these experiments 63 was modified from a previous report 64. Using a two-step photolithography process (photoresist Su-8 2007 and Su-8 2100), we fabricated the master with a positive relief of two heights. The chamber consisted of separate cell body and axon compartments with microchannels linking the two compartments. The cell body compartment was 100 μm in height and was used to deliver neurons, whereas the microchannels were 3-4 μm in height and were used to control axon growth. The master was replicated by curing the PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) pre-polymer with a curing agent at a ratio of 10:1. After baking 2 h at 80 °C, the PDMS mold was peeled off of the master, and the chamber was obtained by placing the mold on a poly D-lysine-coated glass bottom dish.

Immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry

Cells grown on coverslips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Cells and cryostat sections were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies (Supplementary information, Table S1) overnight at 4 °C followed by secondary antibodies conjugated with FITC or/and Cy3 or/and Cy5 (1:100, Jackson laboratory) at 37 °C for 45 min. They were then mounted and scanned with the Leica SP2 confocal microscopy system (Leica). For the sciatic nerve culture experiments, methanol-fixed nerves were incubated with the indicated primary antibodies and corresponding secondary antibodies. Co-localization was analyzed with the co-localization module of the Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software and defined as the overlapping area with a mean diameter ≥ 2 pixels between two puncta acquired with at least 3 pixels per mean diameter. We performed co-localization analyses of samples from the proximal and distal ends of cultured and freshly collected nerves. Then, the percentage ratios of proximal to distal ends were obtained. For the DRG-sciatic nerve culture experiments, cryostat sections of DRG neurons were directly incubated with donkey anti-rabbit Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:50) and simultaneously co-stained with a guinea pig-derived antibody to label the native P2X3 receptors in DRG neurons. Next, the immunofluorescence intensities of the retrogradely transported P2X3 receptors in P2X3 receptor-positive or negative neurons, from which the background signals were subtracted, were obtained using the Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software.

For non-permeabilized staining, HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP were pre-incubated with a rabbit antibody against Myc (1:50, Sigma) for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then treated with the indicated drug, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody. The endocytosis level for each cell under different conditions was calculated as the percentage of intracellular versus whole-cell immunofluorescence intensity using the Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software.

Surface biotinylation

HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP were serum-starved and biotinylated with 0.25 mg/ml cleavable Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce) in PBS containing Mg2+/Ca2+ for 45 min at 4 °C followed by quenching with glycine for 20 min. The cells were treated with the indicated drugs for 30 min at 37 °C and then stripped with a glutathione solution (50 mM glutathione, 75 mM NaCl, 75 mM NaOH and 1% BSA) for 40 min. The stripping efficiency was determined in the biotinylated cells immediately after glutathione stripping. The cells were lysed in RIPA buffer, and the lysates were incubated with neutravidin beads. The pull-down samples were processed for western blotting.

DRG neurons in the microfluidic chamber were serum-starved for 20 h, and the axon surface proteins in the axon compartment were biotinylated with 1.1 mg/ml Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce) in PBS containing 1 mg/ml glucose for 30 min at 4 °C. The axon compartment was treated with the indicated drugs for 30 min at 37 °C. Then the cell bodies were lysed and pulled down with the neutravidin beads.

Western blotting

The tissue and cell lysates or beads were incubated in SDS-PAGE loading buffer for 20-30 min at 50 °C. The samples were separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred, probed with the indicated antibodies (Supplementary information, Table S1), and visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences). The intensity of the immunoreactive bands was analyzed with the Image-Pro Plus 5.1 software. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

H-Ras activation

A Ras-activation assay kit was purchased from Millipore. After different treatments, HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP were lysed and incubated with Raf1 Ras-binding domain (RBD) agarose beads for 30 min at 4 °C. The beads were processed for western blotting and probed with an antibody against H-Ras.

Organelle immunoprecipitation

The sciatic nerve axoplasm was freshly collected in buffer (0.1% BSA, 10 mM NaF in PBS with protease inhibitors) and submitted to immunoprecipitation with a P2X3 antibody in the presence of Trueblot beads (eBioscience). Beads were intensely washed four times in PBS, and the supernatant was processed for western blotting.

Extraction of membrane lipid rafts

HEK293 cells expressing P2X3-Myc-GFP were scraped into 2 ml 500 mM Na2CO3 (pH 11) and incubated on ice for 20 min. The cells were sonicated and brought to 45% sucrose by mixing an equal volume of 90% sucrose in MBS (50 mM 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) and 300 mM NaCl, pH 6.5). The cell lysates were loaded into the bottom of ultracentrifuged tubes, overloaded with 4 ml of 35% sucrose and 4 ml of 5% sucrose in MBS (25 mM MES and 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.5) and centrifuged at 180 000× g for 20 h at 4 °C. Twelve fractions were collected from the top to the bottom of the tubes. All fractions were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and then processed for western blotting. For the detection of lipid raft-localized P2X3 receptors in sciatic nerves, the axoplasm was centrifuged 3 000× g for 10 min. The postnuclear supernatant was centrifuged at 100 000× g for 1 h to yield membrane and vesicular pellets, followed by extraction of the lipid raft described as above.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording

Whole-cell currents were recorded 2 days after the induction of the transient expression of P2X3-Myc-GFP or mRFP-P2X3-Myc in HEK293 cells with an EPC9 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik) at room temperature. All recordings were made at a holding potential of −60 mV. The following external (bath) and internal (pipette) recording solutions were used (in mM): internal- 140 CsCl, 11 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH was adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH; external- 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH (all Sigma). A test solution containing 10 μM α, β-MeATP was added to the cell vicinity through 10-μl pipettes with flow controlled by computer-operated solenoid valves for 3 s each time.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using PRISM (GraphPad Software) with a two-tailed paired or unpaired Student's t-test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30930044) and the National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB912001, 2007CB914501).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Material

The distal end of sciatic nerve connected with DRG was incubated with a normal IgG for the indicated times.

Depletion of extracellular Ca2+ had no effect on the ATP-dependent endocytosis of P2X3 receptor.

α, β-MeATP treatment applied directly to the cell body of cultured DRG neurons activated ERK and CREB within 5 min.

Dynein complex mediated the retrograde transport of P2X3 receptors.

α, β-MeATP-induced endocytosis of P2X3-Myc-GFP rather than α, β-MeATP-induced ERK activation via P2X3 receptor is dependent on dynamin.

Movement of mRFP-P2X3-Myc-positive puncta in DRG neuron axons. mRFP-P2X3-Myc was expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and its axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was 0.5 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

Movement of TrkA-GFP-positive puncta in DRG neuron axons. TrkA-GFP was expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and its axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was 0.5 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

Movement of the puncta containing GFP-Rab7WT or/and mRFP-P2X3-Myc in DRG neuron axons. GFP-Rab7WT and mRFP-P2X3-Myc were co-expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and their axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was ∼0.4 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

Movement of the puncta containing GFP-Rab5WT or/and mRFP-P2X3-Myc in DRG neuron axons. GFP-Rab5WT and mRFP-P2X3-Myc were co-expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and their axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was ∼0.4 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

The retrograde transport of mRFP-P2X3-Myc was disrupted by the overexpression of GFP-Rab7T22N in DRG neuron axons. GFP-Rab7T22N and mRFP-P2X3-Myc were co-expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and their axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was ∼0.4 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

The retrograde transport of mRFP-P2X3-Myc was disrupted by the overexpression of GFP-Rab5S34N in DRG neuron axons. GFP-Rab5S34N and mRFP-P2X3-Myc were co-expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and their axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was ∼0.4 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

Movement of GFP-H-Ras and mRFP-P2X3-Myc in DRG neuron axons. GFP-H-Ras and mRFP-P2X3-Myc were co-expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and their axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was ∼0.5 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

Movement of DsRed1-MEK1 and P2X3-GFP-Myc in DRG neuron axons. DsRed1-MEK1 and P2X3-GFP-myc were co-expressed for 48 h in cultured DRG neurons, and their axonal movement was observed using a Perkin Elmer UltraView Vox system. The cell body is on the right side of the video. The capture rate was ∼0.4 fps. The movie is played at 15 fps.

Antibody company and working concentration

References

- Goldstein LS, Yang Z. Microtubule-based transport systems in neurons: the roles of kinesins and dyneins. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:39–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Takemura R. Molecular motors in neuronal development, intracellular transport and diseases. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa N, Takemura R. Molecular motors and mechanisms of directional transport in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:201–214. doi: 10.1038/nrn1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CL, Mobley WC. Long-distance retrograde neurotrophic signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Pierchala BA, Ciarallo CL, Ginty DD. An NGF-TrkA-mediated retrograde signal to transcription factor CREB in sympathetic neurons. Science. 1997;277:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delcroix JD, Valletta JS, Wu C, et al. NGF signaling in sensory neurons: evidence that early endosomes carry NGF retrograde signals. Neuron. 2003;39:69–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, North RA. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature. 2006;442:527–532. doi: 10.1038/nature04886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Burnstock G, McMahon SB. The expression of P2X3 purinoreceptors in sensory neurons: effects of axotomy and glial-derived neurotrophic factor. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;12:256–268. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic SD, Kassotakis LC, Oglesby IB, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of P2X3 purinoceptors in sensory neurons in naive rats and following neuropathic injury. Pain. 1999;80:273–282. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. P2X receptors in sensory neurones. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:476–488. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J, Patel S, Dorn G, et al. Functional downregulation of P2X3 receptor subunit in rat sensory neurons reveals a significant role in chronic neuropathic and inflammatory pain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8139–8147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08139.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore P, Kage K, Mikusa J, et al. Analgesic profile of intrathecal P2X3 antisense oligonucleotide treatment in chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain states in rats. Pain. 2002;99:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaraughty S, Wismer CT, Zhu CZ, et al. Effects of A-317491, a novel and selective P2X3/P2X2/3 receptor antagonist, on neuropathic, inflammatory and chemogenic nociception following intrathecal and intraplantar administration. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:1381–1388. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souslova V, Cesare P, Ding Y, et al. Warm-coding deficits and aberrant inflammatory pain in mice lacking P2X3 receptors. Nature. 2000;407:1015–1017. doi: 10.1038/35039526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu I, Iida T, Guan Y, et al. Enhanced thermal avoidance in mice lacking the ATP receptor P2X3. Pain. 2005;116:96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA. P2X3 receptors and peripheral pain mechanisms. J Physiol. 2004;554:301–308. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.048587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields RD, Eshete F, Stevens B, Itoh K. Action potential-dependent regulation of gene expression: temporal specificity in Ca2+, cAMP-responsive element binding proteins, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7252–7266. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07252.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino D, Tokunaga A, Tachibana T, et al. The role of ERK signaling and the P2X receptor on mechanical pain evoked by movement of inflamed knee joint. Pain. 2006;123:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Jahn R, Dahlstrom A. Rab3a, a small GTP-binding protein, undergoes fast anterograde transport but not retrograde transport in neurons. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995;67:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry IA, Stockel K, Thoenen H, Iversen LL. The retrograde axonal transport of nerve growth factor. Brain Res. 1974;68:103–121. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90536-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi J, Fujitani M, Endo M, et al. Rap1 is involved in the signal transduction of myelin-associated glycoprotein. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:408–419. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaumont S, Jiang LH, Penna A, North RA, Rassendren F. Identification of a trafficking motif involved in the stabilization and polarization of P2X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29628–29638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403940200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MF, Burgard EC, McGaraughty S, et al. A-317491, a novel potent and selective non-nucleotide antagonist of P2X3 and P2X2/3 receptors, reduces chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:17179–17184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252537299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]