Abstract

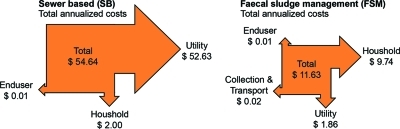

A financial comparison of a parallel sewer based (SB) system with activated sludge, and a fecal sludge management (FSM) system with onsite septic tanks, collection and transport (C&T) trucks, and drying beds was conducted. The annualized capital for the SB ($42.66 capita–1 year–1) was ten times higher than the FSM ($4.05 capita–1 year–1), the annual operating cost for the SB ($11.98 capita–1 year–1) was 1.5 times higher than the FSM ($7.58 capita–1 year–1), and the combined capital and operating for the SB ($54.64 capita–1 year–1) was five times higher than FSM ($11.63 capita–1 year–1). In Dakar, costs for SB are almost entirely borne by the sanitation utility, with only 6% of the annualized cost borne by users of the system. In addition to costing less overall, FSM operates with a different business model, with costs spread among households, private companies, and the utility. Hence, SB was 40 times more expensive to implement for the utility than FSM. However, the majority of FSM costs are borne at the household level and are inequitable. The results of the study illustrate that in low-income countries, vast improvements in sanitation can be affordable when employing FSM, whereas SB systems are prohibitively expensive.

Introduction

The United Nations, World Bank, and World Health Organization consider onsite septic tanks, onsite ventilated improved pit latrines (VIPs), and centralized sewer-based (SB) systems to be equivalent “improved” sanitation systems in meeting the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for sanitation.1 However, the management or treatment of fecal sludge from the onsite technologies is not included in their definitions. The unfortunate result is that frequently development projects do not address fecal sludge or include a comprehensive fecal sludge management (FSM) plan.2 SB systems include household connections, trunk lines, and pumping stations for wastewater conveyance, a centralized wastewater treatment plant (WWTP), and resource recovery or disposal of treatment end-products. Onsite sanitation technologies, such as septic tanks and ventilated improved pit latrines (VIPs), each represent only one component of a comprehensive FSM system. Just as with SB systems, a complete FSM system must also include fecal sludge collection and transport (C&T), a treatment plant, and resource recovery or disposal of treatment end-products.3,4

Previously, onsite sanitation systems were considered to be temporary solutions until SB systems could be implemented and are still typically only considered to be permanent, viable solutions for rural areas.5 However, the perception of onsite or decentralized sanitation technologies is gradually changing and is increasingly being considered as long-term, sustainable options in urban areas, especially in low- and middle-income countries that do not have sewer infrastructures.2 This is an important development for the design approach of sanitation systems and is especially relevant when taking into account the current reality that 65–100% of sanitation in urban areas of sub-Saharan Africa is provided with onsite technologies.6 Management of the fecal sludge from these onsite technologies needs to be implemented to ensure that improved sanitation is really being provided.

Adequate financial information is lacking for decision makers to be able to compare the associated capital and operating costs of SB and FSM systems. The capital and operating costs of some onsite technologies have been evaluated in low-income countries, but not for a comprehensive FSM system,7,8 and the costs of FSM and SB systems have been compared, but not for low-income countries.9 There is a lack of information to use for financial analyses, as comprehensive FSM systems have not been extensively implemented. This experience is necessary to determine actual costs associated with FSM systems and to be able to compare costs and select the optimal type of sanitation system for each given context. The ongoing annual operation and maintenance costs are as important to consider as capital investments when evaluating the financial viability of SB and FSM systems. Not planning for this has frequently resulted in failures and/or the long-term reliance on external subsidies.2 It is also important to consider the overall cost and affordability for each stakeholder in the system to ensure there are adequate funds for capital and operating costs and to ensure an equitable and sustainable sanitation system.10,11

Dakar, Senegal provides a unique opportunity to compare the capital and operating costs of a SB and FSM system under the same operating conditions as the two types of systems currently exist side by side. Operating parameters will change the cost of sanitation systems in every location where they are implemented, but a comparison of the two types of systems under the same operating conditions in a low-income country has never been possible before. This study evaluates the capital and operating costs of the parallel SB and FSM systems and determines the financial flows of major stakeholders in the two systems. The objective of this study was to make a financial comparison for the two types of systems under the same operating conditions, and based on actual capital and operating costs of full-scale, implemented systems.

Materials and Methods

Study Area

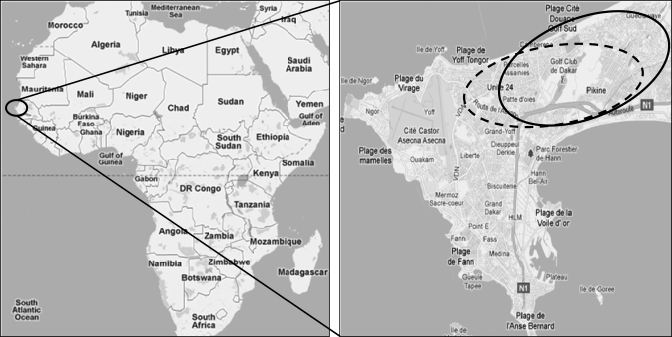

The metropolitan population of Dakar, Senegal is 2.5 million residents. As shown in Figure 1, Dakar is located on a peninsula on the Atlantic Ocean. The soil is sandy, and the topography is relatively flat. 70% of the city is served by a FSM system including septic tanks at the household level, and 30% by a centralized SB system. This study focused on the Cambérène area of Dakar, as it provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the capital and operating costs of existing side by side FSM and SB systems. Cambérène is comprised of the districts Parcelles Assainises, Grand Yoff, Guediawaye, and Hann, with fecal sludge and wastewater both being treated in parallel systems at the Cambérène treatment plant. The population of Cambérène is 500,000 residents, the population density is 22,000 capita km–2, and each household has an average of 10 residents.12,13 This analysis was based on the assumption that both systems are equivalent and are providing the same service (i.e., adequate protection of human and environmental health).

Figure 1.

Map on left depicting location of Dakar, Senegal. Map on right depicting location of study area in Dakar. Area of fecal sludge management system (FSM) shown with solid line, area of sewer based (SB) system with dashed line (Google).

Sewer Based (SB) System

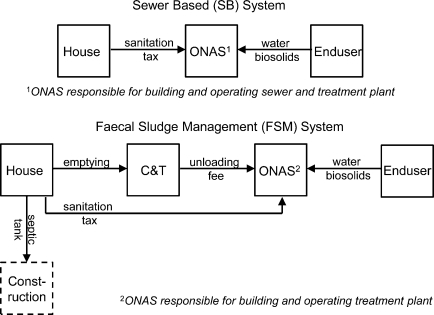

The Cambérène SB system includes 340 km of trunk lines, 26 pumping stations, and a WWTP. As shown in Figure 2, for this analysis stakeholders that were considered in the SB service chain were household level users, the Senegal National Sanitation Utility (ONAS) that is responsible for operation and maintenance of the SB system, and end users of treatment end-products. Prior to primary treatment, the WWTP process consists of screening and fat, oil grease, and sand removal. The primary treatment consists of two settling tanks that together have a capacity of 19,200 m3 day–1. Primary treatment is followed by activated sludge treatment, with a design capacity of 9,600 m3 day–1 (at the time of the study, the capacity has since been increased). Following clarifiers, the solid fraction goes to anaerobic digestion, including methane gas capture for onsite power generation. The biosolids are sold to building and public works companies which use them as a soil amendment for urban green ways. There is tertiary treatment with a design capacity of 5,700 m3 day–1 that consists of sand filters and chlorination for partial reclamation of the effluent. The tertiary treated fraction is sold to neighboring golf courses for irrigation, and the secondary treated effluent is discharged to the ocean.

Figure 2.

Financial flows between stakeholders in existing sewer based (SB) and fecal sludge management (FSM) systems. Dashed line represents stakeholder not included in this analysis.

Fecal Sludge Management (FSM) System

As shown in Figure 2, for this analysis stakeholders that were considered in the FSM service chain were household level users, private collection and transport (C&T) businesses that empty the fecal sludge with vacuum trucks from onsite septic tanks and transport it to the treatment facility, ONAS who is responsible for operation and maintenance of the FSTP, and end users of treatment end-products. The FSTP consists of settling/thickening tanks followed by unplanted drying beds, with the effluent going to the WWTP. The plant has been in operation since 2006 and was designed to receive 100 m3 day–1 of FS. Following treatment, the biosolids from the FSTP are also sold to building and public works companies.

Determination of Costs and Financial Flows

The financial flows considered in this analysis were those of the major stakeholders and of the most significant components of the FSM and SB sanitation systems. Details of determined costs and assumptions are presented in the Supporting Information. The study did not include subsidies by external funding agencies, as they were not considered to be a part of a financially sustainable system.

The methodology consisted of the following steps: 1. Determining capital and operating costs of the FSM and SB systems through existing reports, databases, and interviews with stakeholders. 2. Itemizing capital and operating costs according to the major components of each system. 3. Evaluating the financial flows of stakeholders relevant to each system component. 4. Converting the financial flows to an annualized per capita basis, in order to provide a method of comparison between the FSM and SB sanitation systems.

A real interest rate of 5% was assumed for the lending interest rate adjusted for inflation based on values used by the World Bank. An exchange rate of 500 West African Francs (CFA) to 1 United States Dollar (USD) was assumed, and capital and annual operating costs were expressed as USD capita–1year–1. Units of energy were expressed in mega-joules (MJ) capita–1 year–1. The price for diesel oil and electricity were set at average prices in Dakar of 1.4 USD for 1 L of diesel oil containing 42 MJ of energy, and 0.2 USD for 1 Kwh of electricity containing 3.6 MJ based on reported city statistics.12 The assumed service lives are provided in the Supporting Information, and they are the same as those defined by ONAS in their financial model,14 except for the items “septic tank” and “emptying truck” which were estimated based on previous operational experience determined through interviews.

The annualized cost of capital and operating costs were calculated over the service life of the SB and FSM systems with the following formula

| 1 |

where ACo = annualized cost of sanitation system component o (USD capita–1 year–1), Co = capital cost of sanitation system component o (USD capita–1), no = service lifetime of sanitation system o (years), i = real interest rate, and Fo = annual operating cost of sanitation system component o (USD capita–1 year–1).

Costs for Sewer Based (SB) System

The capital costs for components of the SB system include household connections, sewer network, pumping stations, and WWTP. Capital costs were mostly obtained from the financial model of the ONAS departments of Accounting and Financial Management.14 However, costs associated with the sewer network and pumping stations could not be obtained from ONAS as the records were incomplete. Capital costs for the sewer were estimated based on the Sahm Notaire area in the District of Guédiawaye, as it is topographically representative of Dakar, the demographics and population density of the two areas are very similar, and detailed financial information was available from a sewer project that had been implemented there. Sahm Notaire has a population of 72,000 residents, 47 km of trunk lines, and three pumping stations. The capital costs of the sewer for the whole Cambérène area were estimated to be proportional to the length of the network, the number of pumping stations, and the number of residents connected to the sewer. The capital cost for the WWTP was obtained from ONAS records, and a surcharge of 15% was added to include the preliminary design studies and project management. The costs were then adjusted for inflation to 2008 equivalents, the year the data for this study was conducted.

Negative and positive annual operating costs for the SB system include sewer network, pumping stations, WWTP, treatment end-products, and the sanitation tax paid by every resident based on their drinking water consumption. ONAS financial records for 2007 were used to determine operating costs and to categorize them based on component and exact nature of cost. The valorization of treatment end-products was also considered, as methane is captured and used for energy production, reclaimed water is sold for irrigation, and biosolids as a soil conditioner. A sanitation fee of $0.1 m–3 is paid by all Dakar residents connected to the drinking water supply system based on consumption. ONAS does not have a record of how much this contributes to the operating costs, and so it was estimated to be $2 capita–1 year–1 based on the average water consumption in Dakar of 57 L capita–1 day–115,16. For conversion to a per capita basis, the number of residents served by the Cambérène WWTP in 2008 was estimated to be 230,000 based on the known 20,410 households that were connected in 2004, an annual population growth of 2.96% and an average of 10 residents per household.12,13

Costs for Fecal Sludge Management (FSM) System

The capital costs for the FSM system include installation of septic tanks, vacuum trucks purchased by C&T companies, and the FSTP. The average cost of septic tank installation was based on ONAS financial records. Subsidies for septic tanks are frequently funded through international donors, but for modeling purposes it was assumed that this cost is paid by the household. The main capital cost for C&T companies is the purchase of a vacuum truck. It was assumed that each C&T company owns one truck based on the information reported in Mbéguéré (∼1 truck per 10,000 capita).17 The capital costs of the FSTP were obtained from ONAS financial records.18 A surcharge of 15% was added to include the overhead associated with design studies and project management. The costs were then adjusted for inflation to the year 2008.

Negative and positive annual operating costs for the FSM system include emptying septic tanks, C&T companies, the FSTP, and the valorization of treatment end-products. The fees paid by the household were estimated based on values reported by Mbéguéré.17 The annual operating costs for C&T companies were based on one 10 m3 capacity truck performing four round trips a day between the FSTP and households, as reported by Gning,13 and also included a discharge fee at the FSTP of $0.4 m–3. The operation and maintenance costs for the FSTP were obtained from ONAS financial records for 2007. FSTP end-products (biosolids) are sold to building and public works companies for $0.8 m–3, based on an analysis of performance and quantity of end-products.19 For conversion to a per capita basis, the number of residents served by the FSTP was estimated to be 41,500 residents based on the design capacity (100 m–3 day–1), 260 days of operation per year, and FS production of 2.7 L capita–1 day–1.

Results and Discussion

Capital and Operating Costs

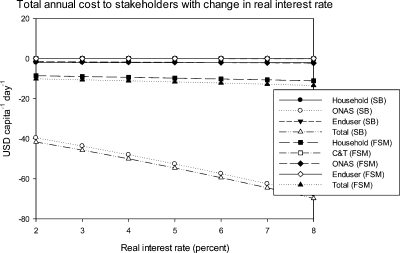

The capital and operating costs that were determined based on this research, and all assumptions that were derived for calculations, are presented in the Supporting Information. The results of the annual value analyses for capital and operating costs for the FSM and SB systems are presented in Table 1. The annualized capital cost for the SB system ($42.66 capita–1 year–1) is ten times higher than for the FSM system ($4.04 capita–1 year–1). The total operating costs for the SB system ($11.98 capita–1 year–1) is also higher than for the FSM system ($7.58 capita–1 year–1) but only 1.5 times higher. The combined capital and operating costs of the SB system ($54.65 capita–1 year–1) is five times more expensive than the FSM system ($11.62 capita–1 year–1). A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate the validity of assumptions that have the greatest impact on the financial model. As illustrated in Figure 3, changes in the real interest rate only make a significant impact on the annualized capital costs of the SB system, but at every rate the SB system is still much more expensive to implement than the FSM system. In addition, changing the lifetime of the septic tank from 50 to 30 years only made a difference of $0.51 capita–1 year–1 to the household. Changing the sewer lifetime from 30 to 50 years resulted in a change of $3.04 capita–1 year–1 or only 6% of the annualized capital sewer cost.

Table 1. Annualized Capital and Operating Cost Results for Fecal Sludge Management (FSM) and Sewer Based (SB) Systemsg.

| sewer

based (SB) |

fecal sludge management (FSM) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| house | ONAS | end user | total | house | C&T | ONAS | end user | total | |

| Annualized Capital Costs (Per Capita*Year) | |||||||||

| household connectiona | 0.00 | –4.98 | 0.00 | –2.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| collection conveyanceb | 0.00 | –30.20 | 0.00 | 0.00 | –0.28 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| treatment plantc | 0.00 | –7.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | –1.03 | 0.00 | ||

| total | 0.00 | –42.66 | 0.00 | –42.66 | –2.74 | –0.28 | –1.03 | 0.00 | –4.04 |

| Annual Operating Costs (Per Capita*Year) | |||||||||

| collection conveyanced | 0.00 | –6.64 | 0.00 | –5.00 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| sanitation taxe | –2.00 | 2.00 | 0.00 | –2.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| treatment plantc | 0.00 | –6.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | –0.84 | 0.00 | ||

| valorization endproductsf | 0.00 | 1.13 | –0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | –0.01 | ||

| total | –2.00 | –9.97 | –0.01 | –11.98 | –7.00 | 0.26 | –0.83 | –0.01 | –7.58 |

| Capital and Annual Operating Costs Combined (Per Capita*Year) | |||||||||

| total | –2.00 | –52.63 | –0.01 | –54.64 | –9.74 | –0.02 | –1.86 | –0.01 | –11.63 |

Household connection (capital) = household sewer connection (20 year lifetime), septic tank (50 year lifetime).

Collection conveyance (capital) = sewer and pumping stations (30 year lifetime), vacuum trucks (15 year lifetime).

Treatment plant (capital and operating) = wastewater treatment plant, fecal sludge treatment plant (30 year lifetime).

Collection conveyance (operating) = sewer, pumping stations, onsite emptying fee, truck transport.

Sanitation tax (operating) = sanitation tax paid by every resident based on water consumption.

Valorization end-products (operating) = biogas, reclaimed water, biosolids.

Brief explanations are provided, and further details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Change in total annualized capital and operating cost to stakeholders based on changes in the real interest rate. SB = sewer based system, FSM = fecal sludge management system.

The annual per capita cost ($54.64 capita–1 year–1) for the SB system is much lower compared to similar systems in other locations, for example the Danube region of Europe ($120 capita–1 year–1).20 This is due to differences in factors such as labor rates and electricity costs. However, in the SB system 67% of the overall cost is due to construction and operation of the sewer infrastructure, and 66% of the WWTP operating budget is due to electricity. This is similar to countries in other regions, where it is well established that with conventional centralized treatment the sewer infrastructure represents the majority of the annualized cost, and with activated sludge treatment electricity represents a significant portion of the WWTP operating costs.21 There are many parameters that will impact operating costs when comparing similar systems in diverse locations. For example, Dakar’s location on a peninsula in the Atlantic Ocean increases the cost of the sewer, as the flat topography requires more pumping stations and the sewers frequently clog from an influx of sand. The relatively high population density (22,000 capita km–2) also means that less energy intensive centralized treatment options that require more land are not feasible (e.g., lagoons or ponds), but an increased population density can also result in lower per capita costs.

The substantial difference in annualized costs between the FSM and SB systems are largely explained by the significant cost of the sewer network and a less energy intensive treatment process (electricity only accounts for 8% of the FSTP operating costs). There are also many factors that will impact the cost of FSM when comparing among different locations. One of the most important factors to consider is regional fecal sludge characteristics, which vary widely depending on the type of onsite technologies. The per capita production of fecal sludge in Dakar (2.7 L capita–1 day–1) is relatively high compared to other countries in West Africa, for example 1 L capita–1 day–1 in Accra, Ghana.22 The higher volume is due to an increased prevalence of flush toilets, access to drinking water, and high groundwater table. The high water table results in infiltration of septic systems and the fecal sludge being less concentrated (4.5 g total solids liter–1).19 The increased volume and reduced concentration results in an increased emptying frequency of onsite systems22 and a reduced dewatering performance and overall cost efficiency of treatment.23 Utilization of other types of treatment technologies will also have an impact on the overall cost (e.g., planted drying beds, anaerobic treatment). The FSM system could also be further optimized by more efficient billing and tracking of customers, improved quality of septic tanks, and locating fecal sludge transfer or relay stations and FSTPs to reduce transport distance.4

In an evaluation of engineering economics, Maurer24 points out an inherent flaw in comparing decentralized versus SB sanitation systems when converting capital investments to annual equivalents based on their expected life times. A SB system with a 30 year lifetime is typically not designed to reach capacity until near the end of that 30 year period. That means that during a significant portion of the lifetime the system will be operating considerably under capacity, especially in rapidly growing areas. In contrast, a FSM system can operate near capacity and is a modular based system that can readily be expanded to meet actual demands. Maurer24 concludes that when incorporating the actual demand and capacity into an annual equivalent, a FSM system, even with a higher capital investment, can still be more cost-effective than a SB system in rapidly growing areas, conditions that are prevalent in the majority of Sub-Saharan African urban areas. In addition, as illustrated by this analysis, a FSM system typically represents a much lower capital investment than a SB system.

Additional Factors for Consideration

There are also many important factors to consider in an evaluation that do not come across in a strictly financial comparison, for example, because the FSM system is not as reliant on electricity, it will be much more robust in locations like Dakar where frequent power outages occur. The FSM system is much more adaptable to the existing infrastructure, for example, in many dense urban areas of sub-Saharan Africa implementation of a SB system would result in the displacement of many households. The risk of failure is also greatly reduced with a decentralized FSM system, having a much lower impact on the overall system if one component fails (e.g., one truck breaking down versus entire sewer blockage; one septic tank failure versus the WWTP). The FSM system can also be much more readily adapted to growth and densification and is hence more flexible to meet the actual demand for sanitation treatment.

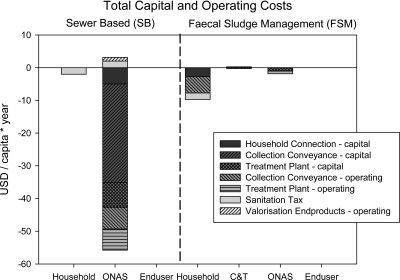

Financial Flows

In addition to considering the total costs it is important to evaluate by whom the costs are borne. As illustrated by Figure 4, the cost of the SB system is mostly the responsibility of ONAS, and the SB system is operating at a huge net loss with only 5.8% of the total annual costs coming in as positive cash flow from the sanitation tax and valorization of end-products. In addition to having a much lower capital investment, the FSM system has a different business model and financial flows, with the costs for the system spread among ONAS, households, and C&T companies, as illustrated by Figure 2 and Figure 4. This is much different than the traditional model of sanitation services being provided solely by a municipality or utility. As a result, the capital investment to ONAS for the FSM system was 40 times lower than the SB system, and hence it was much more affordable for ONAS to implement. C&T companies play an essential role in a FSM system as they provide the means for conveyance. In Dakar, the C&T companies are currently not generating a net profit solely through the collection and transport of fecal sludge as shown in Table 1 and typically rely on emptying storage tanks for commercial industries to generate a profit.17 This also increases the risk of industrial contaminants getting into the FSM stream and having a negative impact on the valorization of end-products. To ensure a reliable FSM system, the profitability of C&T companies needs to be increased. Possibilities include subsidies or tax benefits to reduce the capital investment of vacuum trucks, minimizing transport distances, and extending the hours of operation of the FSTP to allow for more emptying trips.

Figure 4.

Annual capital and operating costs for the sewer based (SB) and fecal sludge management (FSM) sanitation systems.

Although the FSM system is much less expensive to implement and operate than the SB system, the majority of the costs for the FSM system in Dakar are currently borne at the household level, which pays an average of $5.00 capita–1 year–1 to have the fecal sludge from their onsite system removed, $2.74 capita–1 year–1 for septic tank installation, and $2.00 capita–1 year–1 for sanitation tax. The sanitation tax, which goes to ONAS for funding the SB system, is collected from every resident of Dakar that receives drinking water regardless of if they are served by the SB or FSM system. This is particularly inequitable for residents served by the FSM system, as it means they are effectively paying twice for sanitation services (i.e., both the SB and FSM system), and the residents served by the FSM system are in general poorer than those served by the SB system. A maximum of 5% of total household income allocated for drinking water and sanitation is considered to be financially viable.25 The average income in Dakar is $306 household–1 month–1, and for the poorest third of residents it is $202 household–1 month–1.12 The average fee for drinking water is $14.50 capita–1 year–1, which represents 4–6% of household income, together with sanitation the fees amount to 7–10% of household income. Eliminating the sanitation tax for households not on the SB system would reduce it to 6–9% of household income, and septic tank subsidies provided by ONAS would reduce it to 5–8%. For access to sanitation to be affordable and equitable, another source of revenue needs to be developed to reduce the burden at the household level. The high costs result in 37% of the poorest households in Dakar resorting to illegal manual emptying of their onsite systems, which ultimately means that the untreated fecal sludge ends up directly disposed of in the environment.26 In this case, even though access to “improved” sanitation is being met, human and environmental health protection is not actually being adequately provided.

This analysis illustrates the importance of not only changing the approach to designing sanitation systems to meet local demands but also considering business models, including how the systems are managed, owned, and operated. For example, the funds currently generated by ONAS with resource recovery through the valorization of end-products are negligible. Potentially, if markets could be identified and developed for fecal sludge based products, it could provide a financial driver for the entire sanitation system, ultimately increasing access to sanitation by reducing costs at the household level and increasing profits for C&T companies. One promising possibility is if C&T companies could sell fecal sludge to industries that could use it as a fuel (e.g., energy intensive processes like cement production), they could then receive payment for discharge instead of paying a fee. Also important to consider are fee structures, such as a sanitation tax being based on sanitation services provided versus drinking water access. The creation of financially sustainable business models will require innovative thinking about types of technology, who provides services, and who the costs are borne by.

Implications

The analysis in this paper was based on the assumption that both the SB and FSM systems are functioning, providing access to “improved” sanitation, and protecting human and environmental health.1 However, in reality, with the dense population of Dakar, the sandy soils, and the relatively high groundwater table, it most likely means that adequate treatment of septic tank effluent is not being achieved, as this treatment relies on adequate retention time and capacity of soils. In reality, the WWTP and pumping stations also do not operate as they were designed, with frequent power interruptions and pump blockages, leading to frequent raw wastewater discharge directly to the environment.

Although the septic-based FSM system in Dakar is not providing the highest level of human and environmental health protection, it is obviously a huge improvement over the alternative of no management of fecal sludge from onsite septic tanks. The lessons learned by the experience illustrate that in low-income countries vast improvements in sanitation can be affordable when employing FSM, whereas SB systems are prohibitively expensive, and so unattainable in most situations. Another benefit to a septic-based FSM system like that in Dakar is that it provides a gradual way to increase the infrastructure and level of treatment as financial resources become available. For example, the septic based system in Dakar could in the future be modified to a settled sewerage system to provide improved human and environmental health protection.27 The capital costs associated with settled sewerage are well accepted to be less than conventional sewers.28 Other factors that will affect capital and operating costs in different locations include fecal sludge characteristics, geography, climate, population density, treatment technology, onsite storage technology, C&T technology, business models, enduse of treatment products, and location of treatment facilities. In each unique setting, a planning based approach that includes studies of the local conditions needs to be conducted prior to implementation to determine optimal treatment technologies and management structure. Although the costs reported here are specific to the situation in Dakar, the lessons learned can be readily transferred to other locations. One of the most important conclusions of this analysis is that this stepwise approach to implementation can provide the benefit of access to sanitation actually being affordable and achievable, in contrast to only trying to implement SB solutions that were developed for other contexts, are financially unattainable, and when implemented most commonly result in failures.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Senegal National Sanitation Utility (ONAS) for their involvement in this study and openness and willingness to share detailed financial data regarding their sanitation infrastructure, support and collaboration of Doulaye Koné, TOC graphic by Yvonne Lehnhard, and thoughtful reviews by Max Maurer, Tiku Tanyimboh, Elizabeth Tilley, and Magalie Bassan. Funding was received for this study from the Velux Foundation and the Swiss Development Corporation (SDC).

Supporting Information Available

The capital and operating costs that were determined based on this research, and all assumptions that were derived for calculations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Global Water Supply and Sanitation Assessment 2000 Report; World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Koné D. Making urban excreta and wastewater management contribute to cities’ economic development: a paradigm shift. Water Policy 2010, 12, 602–10. [Google Scholar]

- Montangero A.; Koné D.; Strauss M. In Planning towards improved excreta management, IWA 5th Conference on Small Water and Wastewater Treatment Systems, Istanbul, Turkey, 2002; IWA, Ed. Istanbul, Turkey, 2002.

- Tilley E.; Lüthi C.; Morel A.; Zurbrügg C.; Schertenleib R.. Compendium of sanitation systems and technologies; Dübendorf, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Massoud M. A.; Tarhini A.; Nasr J. A. Decentralized approaches to wastewater treatment and management: Applicability in developing countries. J. Environ. Manage. 2009, 90, 652–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss M.; Larmie S. A.; Heinss U.; Montangero A. Treating faecal sludges in ponds. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 42 (10–11), 283–290. [Google Scholar]

- Münch E. V.; Mayumbelo K. M. K. Methodology to compare costs of sanitation options for low-income peri-urban areas in Lusaka, Zambia. Water SA 2007, 33 (5), 593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Boot N.; Scott R.. Faecal sludge management in Accra, Ghana: strengthening links in the chain. In 33rd WEDC International Conference on access to sanitation and safe water: global partnerships and local actions, WEDC, Ed. Accra, Ghana, 2008.

- Pinkham R. D.; Hurley E.; Watkins K.; Lovins A. G.; Magliaro J.; Etnier C.. Valuing Decentralized Wastewater Technologies: A Catolog of Benefits, Costs, and Economic Analysis Techniques; 2004.

- Alexandre O.; Lagange C.; Victoire R.. Stations d’épuration des petites collectivités - Méthodologie et analyse des coûts d’investissement et d’exploitation par unité fonctionnelle (Small waste water treatment plants - Functional unit methodology and analysis of capital and operation costs). Quae: Versailles, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton G.; Pfeiffer V. Blume S.; Münch E. v.; Yaniv M.. Cost and economics. In Sustainable Sanitation Alliance Factsheet Volume 8, Sustainable Sanitation Alliance (SuSanA): 2009; p 8. [Google Scholar]

- ANSD Situation économique & sociale 2005 - région Dakar (Socio-economic status, Dakar); Dakar, Senegal, 2005.

- Gning J. B.Evaluation socio-économique de la filière des boues de vidange dans la région de Dakar (Socio-economic assessment of the feacal sludge sanitation system in Dakar area). Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, Dakar, Senegal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ICEA Modèle de simulation financière du secteur de l’assainissement en milieu urbain (Financial simulation model for the urban sanitation sector), ONAS: Dakar, Senegal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ICEA Modèle de simulation financière du secteur de l’assainissement en milieu urbain (Financial simulation model of the urban sanitation sector).

- ANSD Situation économique & sociale 2005 - région Dakar (Socio-economic situation 2005 - Dakar district). In Ministère de l’économie et des finances du Sénégal: 2005.

- Mbéguéré M.; Gning J. B.; Dodane P. H.; Kone D. Socio-economic profile and profitability of faecal sludge emptying companies. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar]

- GKW Déposantes de boues de vidange à Dakar: dossier d’appel d’offre (Faecal sludge treatment plants in Dakar: Proposal); ONAS: Dakar, Senegal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Badji K.; Dodane P. H.; Mbéguéré M.; Kone D. In Traitement des boues de vidange: éléments affectant la performance des lits de séchage non plantés en taille réelle et les mécanismes de séchage, Actes du symposium international sur la Gestion des Boues de Vidange, Dakar, Senegal, 2011; Eawag/Sandec, Ed. Dakar, Senegal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zessner M.; Lampert C.; Kroiss H.; Lindtner S. Cost comparison of wastewater in Danubian countries. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 62 (2), 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy M. Wastewater Engineering, Treatment and Reuse; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heinss U.; Larmie S. A.; Strauss M.. Solids Separation and Pond Systems for the Treatment of Faecal Sludges in the Tropics; Eawag/Sandec: Dübendorf, Switzerland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dodane P. H.; Mbéguéré M.; Koné D.. Technico-Financial Optimisation of Unplanted Drying Beds. Sandec News n°10 2009, not supplied.

- Maurer M. Specific net present value: An improved method for assessing modularisation costs in water services with growing demand. Water Res. 2009, 43, 2121–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleaver F.; Lomas I. The 5% ’rule’: Fact or fiction?. Development policy review 1996, 14, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bereziat E.The market for mechanical pit-emptying in Dakar & the realities of engaging entrepeneurs; Building Partnerships for Development in Water and Sanitation: United Kingdom, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mara D. D.Low-Cost Sanitation; Wiley: Chichester, U.K., 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Crites R.; Tchobanoglous G.. Small and Decentralized Wastewater Management Systems; WCB and McGraw-Hill: New York, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.