Abstract

Dengue is one of the most important mosquito-borne viral illnesses. The first DHF outbreak was reported from the Philippines in 1953. Initially it was endemic only in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific regions. After about 50 years from the first outbreak, it spread globally to almost every continent including North and South America, Australia and Africa. The majority of cases during the 50s to 80s were children, but today the disease affects both children and adults of all age groups. The disease is caused by dengue viruses that have four serotypes: dengue 1, dengue 2, dengue 3 and dengue 4. Primary infection usually results in milder illness, while more severe disease occurs in cases of repeated infection with different serotypes. In this paper clinical manifestations and management of dengue/DHF/DSS are summarized.

Keywords: dengue, clinical manifestations, early diagnosis, case management

Introduction

The clinical presentations of dengue viral infections range from asymptomatic to severe illness that may lead to death if not properly managed. The symptomatic cases are categorized as undifferentiated febrile illness (UF), dengue fever (DF), dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), dengue shock syndrome (DSS) and unusual dengue (UD) or expanded dengue syndrome (EDS) [1].

• UF cannot be diagnosed clinically and the diagnosis is based on serology or virology.

• DF is considered to be a mild disease because death is rarely reported, but massive bleeding may be associated with DF.

• DHF – clinical presentations during the febrile phase are similar to those in DF. The distinct feature of DHF is the increase in vascular permeability (plasma leakage) that differentiates DHF from DF. The plasma leakage is selective leakage into the pleural and peritoneal cavities that results in pleural effusion and ascites.

• DSS – presentations are the same as those in DHF but the plasma leakage is so severe that the patient develops shock.

• UD – most of the unusual cases are DHF cases with prolonged shock or DHF inpatients with co-morbidities or DHF together with other infections [2].

The majority of the cases are UF and DF. DHF/DSS accounts for about 10% of the symptomatic cases [3].

Case definition of suspected dengue infection

In the first few days of dengue illness, most patients present with acute febrile illness with non-specific signs and symptoms: headache, malaise, nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain and sometimes rash. Retro-orbital pain, myalgia and arthralgia are found mostly in DF patients, but some DHF/DSS may also have these symptoms. The most common bleeding manifestations are petechiae and other symptoms (epistaxis, gum bleeding, hematemesis, melena, hypermenorrhea, hemoglobinuria) which help in identifying early suspected dengue but are often missed by doctors/nurses in busy out-patient or primary care units. Tourniquet test is a simple tool that helps in the early diagnosis of dengue infection.

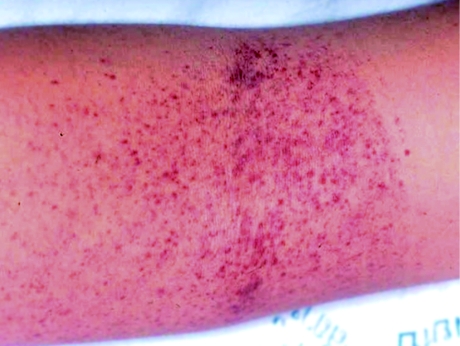

The standard tourniquet test, the Winthrobe technique, involves raising the blood pressure to midway between systolic and diastolic pressure for five minutes. Then release pressure and wait about one minute or until the circulation comes back to normal. Read the result. The positive test is ≥ 10 petechiae/mm3 (Figure 1). The Daisy technique for tourniquet test is easier and can be used in children > five years old and adults. In this technique, pressure is applied to 80 mmHg for five minutes and then released and the result read as in the Winthrobe technique [2].

Fig. 1.

According to the WHO 2011 case definition [1], dengue infection is suspected in a patient with high fever and two of the following signs or symptoms:

• Headache

• Retro-orbital pain

• Myalgia

• Arthralgia/ bone pain

• Rash

• Bleeding manifestations: petechiae, epistaxis, gum bleeding, hematemesis, melena, or positive tourniquet test.

• Leukopenia (WBC ≤ 5,000 cells/mm3)

• Platelet count ≤ 150,000 cell/mm3

• Hematocrit (Hct) rising 5–10%.

In Thailand, the case definition for dengue for surveillance, control and early clinical diagnosis uses the following two criteria: tourniquet test positive or petechiae + leukopenia. The positive predictive value of this case definition is 70–83% [3, 4].

Case definition of DHF

The modified WHO/SEARO 2011 criteria are as follows:

Major criteria: plasma leakage: elevation of Hct ≥ 20%, detection of ascites, pleural effusion by physical examination, chest film (right lateral decubitus position) or ultrasound,

Minor criteria:

1. bleeding or positive tourniquet test.

2. Platelet counts ≤ 100,000 cells/mm3.

Patients who have evidence of plasma leakage do not necessarily have bleeding or positive tourniquet test and their platelet count can be around 100,000 cells/mm3.

DHF severity is divided into four grades according to the severity:

• DHF grade I, DHF grade II – DHF

• DHF grade III and DHF grade IV – DSS

Clinical course of DHF

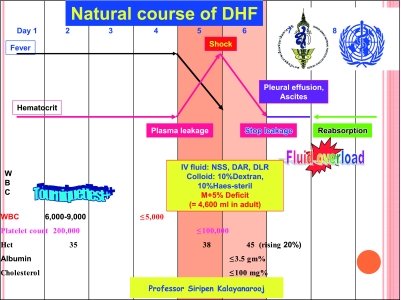

DHF clinical course (Figure 2) is divided into three phases: febrile phase (2–7 days), critical or leakage phase (24–48 hours), and convalescence phase (2–7 days). In the febrile phase, only supportive and symptomatic treatment is conducted. At the end of the febrile phase, plasma leakage begins. More severe cases, i.e. those with moderate to severe plasma leakage and without adequate oral intake, need hospital admission and proper intravenous replacement. Milder cases with minimal plasma leakage and adequate oral intake may recover without treatment. It should be noted that after the critical period, ascites and pleural effusion will be reabsorbed back into the circulation 12–24 hours after leakage stops, i.e. 36–48 hours after shock or 60–72 hours after plasma leakage.

Fig. 2.

Management of patients [2, 3]

The management of patients with dengue infections depends on the phase of illness, i.e. febrile phase, critical/ leakage phase and convalescence phase, as follows:

1. Febrile phase [2–4]: (Early diagnosis of dengue infection: )

Clinical sign:

Rapid diagnostic test:

• NS1Ag test during the febrile phase (first five days of fever): sensitivity 60–70%, specificity >99%

• PCR – good sensitivity and specificity but expensive and not available in most places

• ELISA- IgM, IgG test – not suitable for early diagnosis because the antibody significantly rises after day 5 of fever

(Management)

• Reduction of high fever: paracetamol only, tepid sponge

• Promote oral feeding: soft diet, milk, fruit juice, oral rehydration solution (ORS). Avoid IV fluid if there is no vomiting and moderate/ severe dehydration

• Follow up CBC everyday

• Advise to come back to the hospital ASAP when there is no clinical improvement despite a lack of fever, severe abdominal pain/ vomiting, bleeding, restless/irritable, drowsy, refusal to eat or drink (some patients may be thirsty), urine not passed for 4–6 hours

2. Critical/ Leakage phase: (Early detection of plasma leakage/ shock:)

• Thrombocytopenia, i.e. platelet count ≤ 100,000 cells/mm3, is the best indicator for plasma leakage: Platelet count between 50,000 and 100,000 cells/mm3 – beginning of plasma leakage (about half of DF patients have thrombocytopenia at this level), platelet count < 50,000 cells/mm3 – DHF is most likely and usually indicates that plasma leakage has occured, probably for 24 hours.

• Admit patients with thrombocytopenia and poor appetite/ poor clinical conditions. Consider admitting high risk patients: infants, obese patients, patients with prolonged shock (grade IV), bleeding, encephalopathy, underlying diseases, pregnancy.

• Detection of pleural effusion and ascites by physical examination in the early leakage phase or even at the time of shock is very difficult. Chest film – right lateral decubitus technique, ultrasonogarphy or serum albumin ≤ 3.5 gm% are the alternative ways to detect plasma leakage.

(Proper IV fluid management during the critical period:)

• Isotonic salt solution in the critical period, e.g. 5% dextrose in normal saline solution (NSS), 5% Ringer Acetate, 5% Ringer-Lactate. The 5% dextrose in NSS is preferable because the severe cases needing admission are those with poor appetite, nausea/ vomiting and abdominal pain.

• The total amount of fluid needed during the critical period of 24–48 hours is estimated to be maintenance + 5% deficit (M+5%D), including oral and IV fluids. In DSS patients the duration of IV fluid may be 24–36 hours and in non-shock DHF 48–60 hours.

• The rate of IV fluid should be adjusted according to clinical vital signs (BP, pulse, respiratory rate, temperature), hematocrit (Hct) and urine output (0.5 ml/kg/hr)

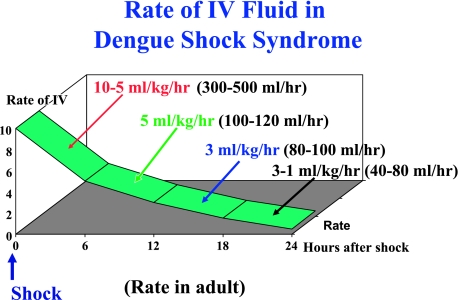

• The rate of IV fluid for shock patients (DHF grade III) is shown in Figure 3. The IV fluid resuscitation for DHF grade III is less than that recommended for other kinds of shock, i.e. only 10 ml/kg/hr, not 20 ml/kg/hr or over. A larger amount of IV fluid is needed for DHF grade IV, but the rate should be reduced to 10 ml/kg/hr as soon as the blood pressure is restored.

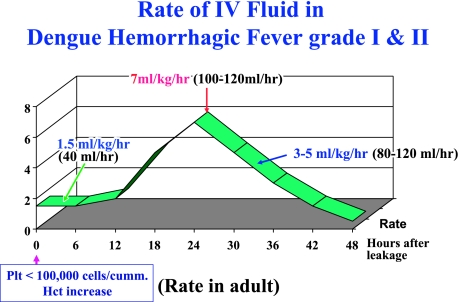

• The rate of IV fluid for non-shock patients (DHF grade I and II) is shown in Figure 4. The administration should begin at a slower rate if leakage is in the earlier stage, i.e. platelet count is between 50,000 and 100,000 cells/mm3. The rate of IV should be more rapid when the leakage has continued for some time, i.e. platelet count < 50,000 cells/mm3.

-

• If the clinical response is not good (re-shock, unstable vital signs, inability to reduce the rate of IV fluid) investigate and correct the following laboratory data:

A – Acidosis – blood gas (capillary or venous), if present, check liver and renal functions. Correct acidosis when blood pH is < 7.35 and HCO3 < 15 mEq/L.

B – Bleeding – Hct: if high, dextran is indicated, if low or not rising, consider blood transfusion and consider giving vitamin K1 intravenously.

C – iCa and other electrolytes: Na, K. Give cagluconate 1 ml/kg/dose diluted twice with IV fluid and IV push slowly. Maximum dose is 10 ml/dose.

S – Blood sugar

• Colloidal solution: only plasma expander that has an osmolarity higher than that of plasma is recommended, e.g. 10% Dextran-40 in NSS. Bolus dose of 10 ml/kg/hr in children or 500 ml/hr in adults is recommended, and this will usually bring the Hct down to 10 points in cases with signs of fluid overload or persistently high Hct.

• In cases with significant bleeding, i.e. > 6–8 ml/kg ideal body weight in children or 300 ml in adult, blood transfusion is recommended as soon as possible. The amount to transfuse is equal to the estimated amount. If it is impossible to estimate (concealed internal bleeding), transfuse 10 ml/kg of fresh whole blood (FWB) or 5 ml/kg of packed red cells (PRC) in children to raise Hct by 5 points. In adults, transfuse 1 unit of FWB or PRC.

• Platelets are indicated in cases with significant bleeding. If the patient already has signs of fluid overload, however, do not give platelets because this will cause fluid overload (possibly acute pulmonary edema). Platelet transfusion is only adjunct therapy, not specific treatment. There is no platelet prophylaxis in children, no matter how low the platelet count. Clinicians may consider prophylactic platelet transfusion in adults with underlying hypertension or heart disease and a platelet count < 10,000 cells/mm3.

• Plasma has almost no role in the management of acute DHF in the critical phase.

• Steroid has no role in the management of DSS.

• At the children’s hospital, Bangkok, DHF/DSS patients were treated with NSS (100%), Dextran-40 (20–25%), blood transfusion (10–15%) and platelet transfusion (0.4%) [3].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

3. Convalescence phase:

• Stop IV fluid when there are signs of recovery: convalescence rash, itching, increase in appetite or > 30 hours after shock and > 60 hours after plasma leakage. Sinus bradycardia may be observed in some patients.

• Patients who have massive ascites and pleural effusion may need diuretic during this period of reabsorption of extravasated plasma into the circulation.

• Some patients may not regain their appetite in this period. This may be due to diuresis and loss of potassium in the urine. Potassium supplement may be necessary in this phase. Fruit (bananas, oranges) and fruit juice are rich in potassium and are preferred by most patients.

• In adults, the convalescence period may extend for 2–4 weeks with fatigue.

4. Management of volume overload [2]

The most common complication in DHF/DSS management is fluid overload, which may lead to heart failure, acute pulmonary edema or even death if not managed properly and timely.

Steps in the management of fluid overload:

-

1) Early detection of signs and symptoms of fluid overload.

Early signs of fluid overload: puffy eyelids, tachypnea, distended abdomen with abdominal discomfort

Late signs of fluid overload = indication for diuretic (furosemide 1 mg/kg/dose)* : Cough, respiratory distress (dyspnea/ orthopnea), very tense abdomen, wide pulse pressure (some may have narrowing of pulse pressure), strong and bounding pulse, hypertension (reabsorption phase), abnormal lung signs (crepitation, rhonchi, wheezing). Urinary catheter should be inserted in every patient with late signs of fluid overload.

2) Know the status of the patient: time after shock or time after plasma leakage. If the patients are still in the leakage phase, dextran bolus is recommended 15–30 minutes before administer furosemide.

3) Status of the patient at that time: shock or non-shock. If the patients are in shock state, dextran bolus is recommended for 15–30 minutes before administer furosemide.

-

4) Assessment and correct associated complications: bleeding, electrolyte/metabolic/acid-base disturbance, liver/renal failure?

* Clinicians are urged to measure the vital signs four times at 15-minute intervals after furosemide administration because furosemide acts for less than 1 hour.

5. Management of DHF with encephalopathy [2]:

Most cases of encephalopathy are observed in DHF patients during or after the critical phase, but it may occur early in the febrile phase. Few cases are found among DF patients. The presentations include behavior change (aggression, violence, vulgar language), consciousness change (irritation, agitation, confusion, hallucinations, coma) and convulsion.

More than half of DHF patients who present with encephalopathy are cases of prolonged shock and liver/renal failure. The other common causes are hyponatremia, hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia. Intracranial bleeding, although quite rare, is usually found in DSS patients with prolonged shock and multi-organ failure and occurs very late, i.e. > 3 days after shock.

Management of dengue encephalopathy is generally the same as that of hepatic encephalopathy, as follows:

1) Maintain adequate airway oxygenation with oxygen therapy. Intubation may be necessary for patients who are in respiratory failure or semi-coma/ coma.

-

2) Prevent/ reduce ICP by the following measures:

Give minimal IV fluid to maintain adequate intra-vascular volume, ideally the total IV fluid should not exceed 80% maintenance

Switch to colloidal solution earlier if Hct continues to rise or a large volume of IV is needed in cases with severe plasma leakage.

Administer diuretic if indicated in cases with signs and symptoms of fluid overload.

Consider steroids to reduce ICP. Dexamethazone 0.5 mg/kg/day IV every 6–8 hours is recommended.

Hyperventilation?

-

3) Decrease ammonia production:

Give lactulose 5–10 ml every 6 hours for induction of osmotic diarrhea.

Local antibiotics to eliminate bowel flora. This is not necessary if systemic antibiotics are given.

4) Maintain blood sugar level > 60 mg%. Recommend glucose infusion rate between 4–6 mg/kg/hour.

5) Correct acid-base and electrolyte balance, e.g. correct hypo/hypernatremia, hypo/hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia and acidosis.

6) Vitamin K1 IV administration: 3 mg for < 1 year old, 5 mg for < 5 years old and 10 mg for > 5 years old and adults.

7) Anti-convulsants should be given for control of seizures; phenobarbital, dilantin and diazepam IV as indicated.

8) Transfuse blood, preferably fresh packed red cells as indicated. Other blood components such as platelets and fresh frozen plasma should not be given because the fluid overload may cause increased ICP.

9) Empiric antibiotic therapy may be indicated if suspected superimposed bacterial infections occur.

10) H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitor may be given to alleviate gastro-intestinal bleeding.

11) Avoid unnecessary drugs because most drugs have to be metabolized by the liver.

12) Consider plasmapheresis or hemodialysis or renal replacement therapy in cases of clinical deterioration.

References

- 1.WHO SEARO. Comprehensive Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever Revised and expanded 2011.

- 2.Kalayanarooj S, Nimmannitya S. Guidelines for Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever Case Management. Bangkok: Bangkok Medical Publisher; 2004.

- 3.Kalayanarooj S.Standardized clinical management: evidence of reduction of dengue hemorrhagic fever case-fatality rate in Thailand. Dengue Bulltetin 1999; 23: 10–16 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalayanarooj S, Nimmannitya S, Suntayakorn S, Vaughn DW, Nisalak A, Green S, Chansiriwongs V, Rothman A, Ennis FA.Can doctors make an accurate diagnosis of dengue? Dengue Bulletin 1999; 23: 1–9 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalayanarooj S, Vaughn DW, Nimmannitya S, Green S, Suntayakorn S, Kunentrasai N, Viramitrachai W, Ratanachu-eke S, Kiatpolpoj S, Innis BL, Rothman AL, Nisalak A, Ennis FA.Early clinical and laboratory indicators of acute dengue illness. J Infect Dis 1997; 176(2): 313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]