Abstract

Rab genes encode a subgroup of small GTP-binding proteins within the ras super-family that regulate targeting and fusion of transport vesicles within the secretory and endocytic pathways. These genes are of particular interest in the protozoan phylum Apicomplexa, since a family of Rab GTPases has been described for Plasmodium and most putative secretory pathway proteins in Apicomplexa have conventional predicted signal peptides. Moreover, peptide motifs have now been identified within a large number of secreted Plasmodium proteins that direct their targeting to the red blood cell cytosol, the apicoplast, the food vacuole and Maurer's clefs; in contrast, motifs that direct proteins to secretory organelles (rhoptries, micronemes and microspheres) have yet to be defined. The nature of the vesicle in which these proteins are transported to their destinations remains unknown and morphological structures equivalent to the endoplasmic reticulum and trans-Golgi stacks typical of other eukaryotes cannot be visualised in Apicomplexa. Since Rab GTPases regulate vesicular traffic in all eukaryotes, and this traffic in intracellular parasites could regulate import of nutrient and drugs and export of antigens, host cell modulatory proteins and lactate we compare and contrast here the Rab families of Apicomplexa.

Keywords: Theileria, Apicomplexa, Rab GTPases, Vesicular traffic

1. Introduction

Apicomplexan parasites are a phylum of medically important infectious organisms responsible for a large number of diseases that afflict mankind and its domestic animals. The phylum contains such notable parasites such as Plasmodium – P. falciparum the causative agent of human malaria; Toxoplasma – T. gondii the causative agent of Congenital Toxoplasmosis; Cryptosporidia – C. parvum and C. hominis the causative agents of persistent diarrhea; Neospora – N. caninum the causative agent of abortion in a wide-range of animals; Babesia – B. bovis the causative agent of Tick fever in cattle and Theileria – T. parva the causative agent of East Coast fever and T. annulata the causative agent of Tropical Theileriosis. Due to their medical importance, the sequence of the genomes of many of these Apicomplexan parasites has been determined, their proteomes compared [1] and transcriptional data exploited [2–5].

Rabs are small GTP-binding proteins that regulate targeting and fusion of transport vesicles within the secretory and endocytic pathways of eukaryotic cells [6]. The sequencing of T. parva and T. annulata has revealed two highly syntenic genomes with 82% nucleotide identity [7] that we have exploited using comparative genomics to characterise the two families coding for Rab GTPases and then to compare them with Rab families from other Apicomplexan parasites. Given the wealth of information available on P. falciparum via PlasmoDB (http://www.plasmodb.org), or GeneDB (http://www.genedb.org) and the fact that the complete family of 11 Rabs has been characterised [8], we have used this family of parasite Rabs as a benchmark for our comparative analysis, particularly with respect to transcription profiling. Moreover, a comparison between Theileria and Babesia parasites that lack a parasitophorous vacuole membrane (PVM) with Plasmodia and Toxoplasma/Neospora parasites that reside within a PVM might throw some light as to a potential role of a given Rab in mediating vesicular traffic across this barrier [9–11]. We have also included in our analysis Cryptosporidia, as these parasites have lost the Apicoplast, an organelle believed to be derived from the chloroplast of an ancestral algal endosymbiont that characterises many Apicomplexan parasites, and to which vesicular traffic is likely to occur [12].

Many microarray studies have been performed using P. falciparum parasites and this has led to the notion that its transcriptional regulation is unusual with peaks of gene expression occurring in waves, where genes encoding related functions (such as invasion) are expressed at the same time [3,4,13,14]. The concept of unusual regulation of transcription in Apicomplexa was reinforced by a study using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) of T. parva transcripts that showed that polyadenylated transcripts corresponding to 86% of T. parva genes had signature sequences in cultured infected lymphocytes harvested at a single time point [15]. Another unusual feature of transcription in Apicomplexa is the abundance of anti-sense transcripts that we will address in detail later. This level of both sense and anti-sense transcripts is consistent with the hypothesis that in Apicomplexa virtually all genes are transcribed at a basal level, but that transcripts for subsets of genes are subject to specific regulatory processes and can accumulate at different points in the life cycle. One way to explain this kind of control is via the recombinatorial binding of different factors to the regulatory regions upstream of coding sequence of P. falciparum genes [16], a notion that could explain the dearth of recognisable transcription factors encoded in the genome [1,17]. We have used previously described algorithms [16] to identify putative factor binding motifs in the regulatory regions of P. falciparum rab genes and we then compared the presence and position of these motifs to the transcription profiles of the different rab genes, as determined from published microarray data [3,4,14].

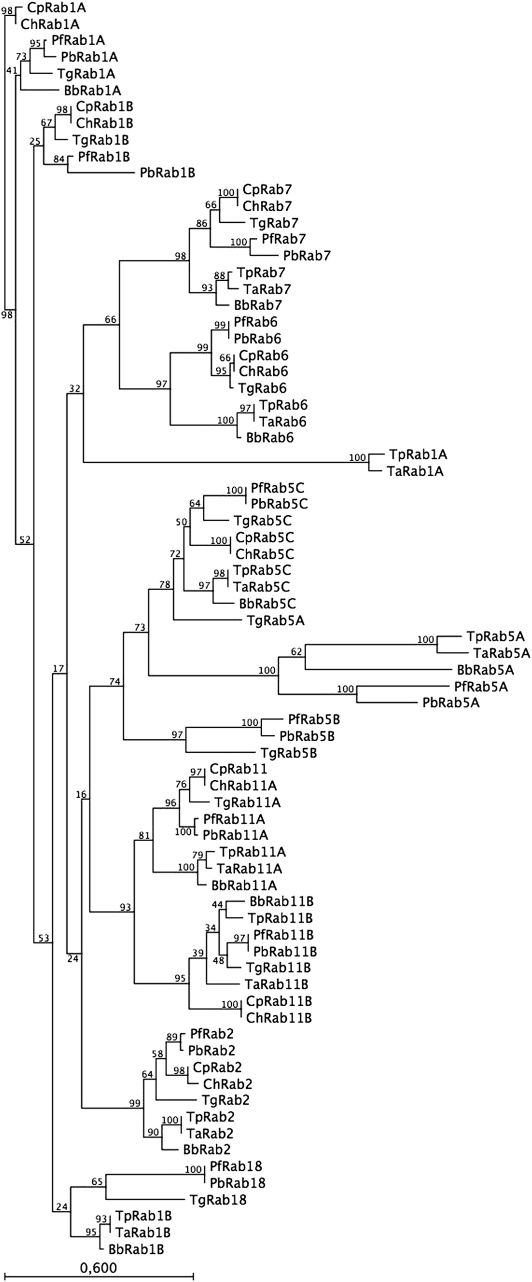

As we have previously shown, phylogenetic analysis allows grouping of different parasite Rabs into clades [8] and such associations allow us to propose similar putative functions for Rabs from the different Apicomplexa. Unlike Plasmodia [8] that have 11 rab genes, Toxoplasma and Neospora (not shown) encode 15 different Rabs probably reflecting their large host range. In contrast, Theileria and Babesia parasites have a smaller family of 9 Rabs, lacking a gene coding for Rab5A and Rab18 and in Cryptosporidia the Rab family is further reduced to only 8, as they also lack Rab5B. This could be taken as suggesting that Rab5A and Rab18 might be involved in vesicular traffic to the PVM, while Rab5B might regulate a trafficking towards the Apicoplast of Plasmodia and Toxoplasma.

2. The Theileria family is made up of 9 Rabs two of which exhibit unusual functional properties

To determine the complete complement of rab genes encoded in the T. parva and T. annulata genomes we performed an exhaustive series of BLAST analyses using P. falciparum rab genes as queries. In this way we established that both Theileria species have just 9 rab genes and that they appear to lack orthologues for rab5b and rab18 (Table 1). We noted the detection of a corresponding T. annulata expression sequence tag (EST) for each rab gene and whether the EST was derived from schizont (infected macrophages) or piroplast (infected red blood cells) mRNA, so as to gain some insight into the expression profile of the T. annulata rab family at two different life cycle stages. Even this rather superficial evaluation of expression profiles demonstrates that 7 out of 9 T. annulata rabs are expressed in infected macrophages clearly suggesting that all rabs are expressed at this stage. The lower number of corresponding piroplast ESTs is probably a reflection of the small size of the piroplast cDNA library [7].

Table 1.

For the 11 different P. falciparum Rabs is given the PlasmoDB identification (ID) and the corresponding accession number

| P. falciparum | ID | Accession numbers | T. parva | ID | T. annulata | ID | Schizont EST | Piro EST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PfRab1A | PFE0690 | AF201953 | TpRab1A | TP04_0644 | TaRab1A | TA10730 | – | – |

| PfRab1B | PFE0625w | AJ409198 | TpRab1B | Tp03_0775 | TaRab1B | TA18180 | + | + |

| PfRab2 | PFL1500w | AJ308736 | TpRab2 | TP01_0877 | TaRab2 | TA06165 | + | – |

| PfRab5A | PFB0500c | AAC71889 | TpRab5A | TP04_0575 | TaRab5A | TA09125 | – | – |

| PfRab5B | MAL13P1.51 | AJ422110 | – | – | ||||

| PfRab5C | PFA0335w | AJ420321 | TpRab5C | TP01_0639 | TaRab5C | TA03030 | + | – |

| PfRab6 | PF11_0461 | X92977 | TpRab6 | TP02_0799 | TaRab6 | TA15190 | – | + |

| PfRab7 | PF10155c | AJ290938 | TpRab7 | TP03_0666 | TaRab7 | TA17640 | + | – |

| PfRab11A | PF130119 | X93161 | TpRab11A | TP01_1204 | TaRab11A | TA09700 | + | – |

| PfRab11B | MAL03P1.205 | AJ879563 | TpRab11B | TP02_0559 | TaRab11B | TA13860 | + | – |

| PfRab18 | PF08_0110 | AJ438271 | – | – |

The T. parva TIGR Database and T. annulata GeneDB identification numbers are given for each of the 9 different Theileria Rabs. When detected the presence of schizont and prioplast ESTs are indicated for each Theileria Rab.

Two T. parva Rab proteins have previously been shown to exhibit unusual functional properties [18]. A Rab1B homologue of T. parva contained a 17 amino acid C-terminal extension and a novel XCX motif for addition of a lipid moiety through isoprenylation that differed from the typical CXC or XCC signal, but was shown to be functional in vitro [18]. Moreover, immunofluorescence indicated that T. parva Rab1B was expressed in schizont-infected lymphocytes with a perinuclear localisation typical for an ER-specific Rab. A second cDNA (GenBank accession number DQ825390) was originally described as being most similar to Rab4 [18]. However, BLAST searches performed against the range of Apicomplexan Rabs as part of this study suggest that it is a Rab11A orthologue. This Rab also contains an unusual sequence feature in having a substitution of Alanine at position 146 located within the third GTP-binding domain motif by a Cysteine. An Alanine residue is typically conserved in this position, not only in Rabs, but also in the entire ras super-family. Inspection of the different parasite genome sequences confirmed the substitution of Ala146 residue by Cysteine in T. annulata and in B. bovis.

3. Transcripts of the T. parva rab family are present in infected T cells

An alternative estimate of gene transcription can be obtained using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) and this has been applied to T. parva using mRNA isolated from infected T cell cultures [15]. We have extracted from this genome-wide data set the MPSS scores for the 9 T. parva rab genes (Table 2). One can readily see what we suspected from the T. annulata-infected macrophage EST collection, namely that transcripts for 7 different rab genes are detected in infected T cells. Although no transcripts were detected for rab1b and rab11b this is due to the absence of a DpnII restriction site that is required in the MPSS technique in order to clone the relevant cDNAs for generation of sequence signatures [15]. Moreover, ESTs were detected for both rabs in T. annulata-infected macrophages (Table 1) consistent with the two genes being transcribed. Taking the T. parva and T. annulata expression profiling data together it seems reasonable to propose that all Theileria rab genes are transcribed in infected leukocytes.

Table 2.

The massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) values, presence of sense and antisense transcripts and chromosomal locations are shown for each of the 9 T. parva rabs

| Name | TPM | Orientation | Chromosome | Locus | Common name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tprab5C | 5 | Sense | 1 | TP01_0197 | GTP-binding protein, putative |

| 53 | Sense | 1 | TP01_0639 | GTP-binding protein Rab5, putative | |

| Tpran | 1178 | Sense | 1 | TP01_0757 | GTP-binding nuclear protein ran, putative |

| Tprab2 | 261 | Sense | 1 | TP01_0877 | GTP-binding protein Rab2, putative |

| Tprab11A | 143 | Sense | 1 | TP01_1204 | GTP-binding protein Rab11, putative |

| Tprab11A | 26 | Anti-sense | 1 | TP01_1204 | GTP-binding protein Rab11, putative |

| 229 | Sense | 2 | TP02_0248 | GTP-binding nuclear protein 1, putative | |

| Tprab6 | 22 | Sense | 2 | TP02_0799 | GTP-binding protein Rab6, putative |

| Tprab11B | none | 2 | TP02_0559 | GTP-binding protein Rab11b, putative | |

| 77 | Sense | 3 | TP03_0502 | GTP-binding protein, putative | |

| 429 | Sense | 3 | TP03_0578 | GTP-binding protein, putative | |

| 539 | Anti-sense | 3 | TP03_0578 | GTP-binding protein, putative | |

| Tprab1B | none | 3 | TP03_0775 | GTP-binding protein Rab1b, putative | |

| Tprab7 | 82 | Sense | 3 | TP03_0666 | GTP-binding protein Rab7, putative |

| Tprab5A | 175 | Sense | 4 | TP04_0575 | GTP-binding protein, Rab5A putative |

| Tprab1A | 4 | Sense | 4 | TP04_0644 | GTP-binding protein, Rab1A putative |

The locus position for each rab is indicated by the corresponding TIGR Database gene ID number. Included for comparison are the MPSS scores for genes coding for number of putative GTP-binding proteins.

An advantage of MPSS is that the score (the number of transcripts sequenced) gives a more readily quantifiable estimate of the level of transcription. The individual scores indicate that different T. parva rab genes are transcribed at varying levels, going from a minimum of 4 for rab1a to 261 for rab2. It should be noted that in general rab gene transcription appears low compared to that of another small GTPase like ran that has a score 10-fold higher (Table 2). The implied level of transcription is also low relative to T. parva genes in general, with the average number transcripts per million (t.p.m) being 232 for sense signatures across the entire genome [15]. This would imply that rab-specific promoters, if they exist, are weak in nature.

There is a growing debate as to the potential role of anti-sense transcripts in P. falciparum, where they can be detected for approximately 12% of all genes [19,20]. Anti-sense transcription could be a phenomenon common to all Apicomplexa, as a similar percentage of genes have anti-sense transcripts in T. parva [15]. Anti-sense transcripts were detected only for rab11a, i.e. 1 out of 9 rab genes (11%), which is in the range described for the whole genome (Table 2). This contrasts with the gene for another GTP-binding protein (TP03_0578) that has 20-fold more anti-sense message. The anti-sense transcripts could not be explained by mRNA coming from another gene being transcribed on the opposite strand of the chromosome. Why there is an abundance of anti-sense transcription in Apicomplexa remains obscure, but it could suggest that transcriptional control in parasites is promiscuous, with the polymerase binding to and transcribing any accessible (chromatin poor) DNA. Another, non-exclusive possibility is that anti-sense transcripts are regulators of gene transcription.

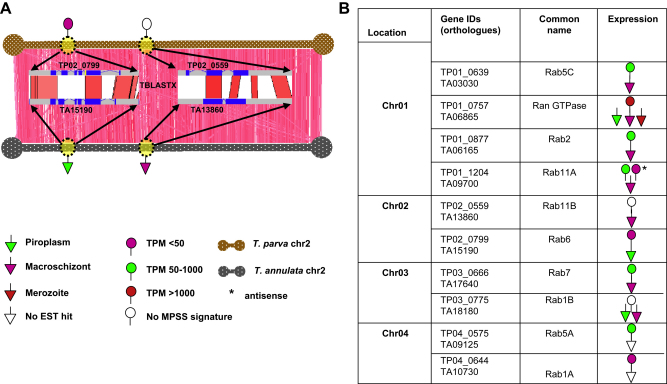

We compared the chromosomal location of each rab gene and the level of transcription and were able to rule out that chromosomal context influences transcription levels (Fig. 1). The 9 different rab genes are distributed over the 4 Theileria chromosomes with no obvious clustering. A similar genome-wide distribution of rab genes has been described for Plasmodia [21,22]. Given the high level of synteny between T. annulata and T. parva genomes each rab gene was positionally conserved located in a similar position in the two species. This is shown schematically for chromosome 2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Positionally conserved rab genes and their expression profiles in Theileria genomes. (A) Artemis comparison tool (ACT) view of conserved gene order (i.e. synteny) between T. annulata and T. parva chromosome 2 is shown. The locations of the Rab6 and Rab11B orthologs within chromosome 2 in T. annulata and T. parva are indicated with yellow spheres. The red lines connecting the 2 chromosomes represent TBLASTX matches. The annotated gene structures of the Rab6 and Rab11B in T. annulata and T. parva are shown as the zoomed in view. (B) The expression levels (as determined by the MPSS data or EST data) of the rab genes, their chromosomal position and orthologous relationships between T. annulata and T. parva are shown in tabular format.

4. Transcription profiling of P. falciparum rab genes derived from microarray analysis

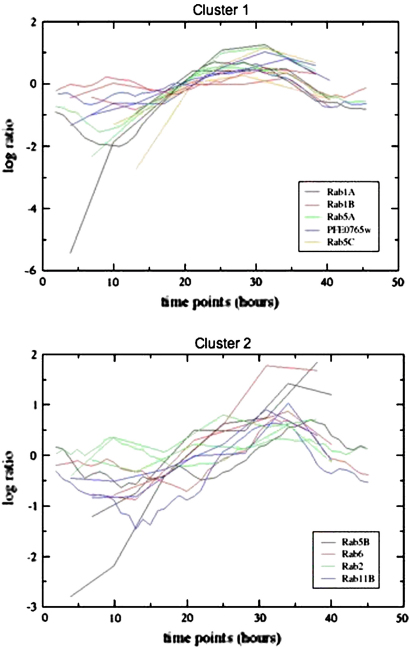

There have been several published studies investigating genome-wide transcription of P. falciparum at different life cycle stages and at different points in intra-erythrocyte development. From these analyses has arisen the notion that genes with similar transcription profiles might be involved in similar biological processes [3,4]. With this in mind we wondered if rabs coding for similar processes like the early steps in endocytosis (Rab5A, 5B, 5C) might have similar profiles to a known Rab5 effector protein such as Vsp34 [23]. Data from a second array [14,24] profiled the transcriptome of P. falciparum at various points during the erythrocytic cycle of the parasite (early and late ring, early and late trophozoite, early and late schizont, free merozoite). The normalised data from both platforms were used separately for unsupervised non-hierarchical clustering (ArrayMiner, Optimal Design) and careful examination of the clusters revealed that the transcripts for rab genes fall into three groups. The rab1a and rab1b, rab5a, rab5c and vps34 (PFE0765w) transcripts can be found in the same cluster and seem to peak at the trophozoite–late trophozoite stage (Fig. 2, top: cluster 1). In contrast, the rab2, rab5b, rab6, and rab11b transcripts fall into another cluster that seems to peak at late schizont stage (Fig. 2, bottom: cluster 2). The 3 other rab genes (rab7, rab11a and rab18) do not appear to share any specific expression profile and hence fail to fall in any cluster.

Fig. 2.

Expression profiles of individual P. falciparum rab genes in asexual life stages of the parasite. The genes rab1a, rab1b, rab5a, rab5c, and PFE0765w (vps34) are found in cluster 1, while rab5b, rab6, rab2, and rab11b are found in cluster 2. Expression profiles for each gene are colour coded as indicated in the figure. The x-axis shows the hours post-infection of a red blood cell by the parasite, and the y-axis shows the log(2) ratio of expression values for each normalised rab gene. For details of the microarray data see Supplementary Fig. S1.

Transcripts from the Rab5 effector vps34 (PFE0765w) are found in the same cluster as rab5a and rab5c, and not in the rab5b cluster. This could be taken as an indication that (1) Rab5B is not involved in the same biological process (endocytosis) as Rab5A and Rab5C and (2) Vps34 is a potential effector of Rab5A and/or Rab5C, but not Rab5B. We have previously pointed out that the presence of a 30 amino acid insertion in the effector domain of Rab5A should confer on its interactions with novel effectors [8]. This logic would favour Vps34 as a Rab5C effector. The dissociation of expression profiles of rab5a and rab5c from rab5b may be related to the observation that Rab5B appears to be a non-functional Rab, lacking the C-terminal prenylation motif necessary for its attachment to the vesicle membrane [8]. In spite of the absence of any prenylation motif, rab5b is transcribed and the coding sequence free of stop codons, implying that it plays some unusual regulatory function. As a non-vesicle associated Rab it is unlikely that Rab5B participates in endocytosis and therefore, perhaps not surprising that its expression profile does not cluster with rab5a and rab5c. Just what is the commonality between rab5b, rab2, rab6 and rab11b suggested by their expression profiles is difficult to ascertain. Why rab7, rab11a and rab18 fail to fall into any cluster is a mystery, especially given that Rab7, like Rab5 is normally a regulator of endocytosis.

5. The presence of specific binding motifs in the promoters of rab genes belonging to expression profiles of clusters 1 and 2

Even though P. falciparum undergoes many developmental changes with large variations in gene expression it encodes relatively few recognisable transcriptional regulators [17]. Recently, using a bioinformatic approach that integrated sequence conservation among species and correlations in mRNA expression (microarray data), 12 novel putative regulatory binding motifs were identified [16]. This analysis proposed a model that suggested that Plasmodium might use combinatorial binding of different protein factors to these motifs in the 5′-upstream regions (“promoters”) of genes to regulate transcription.

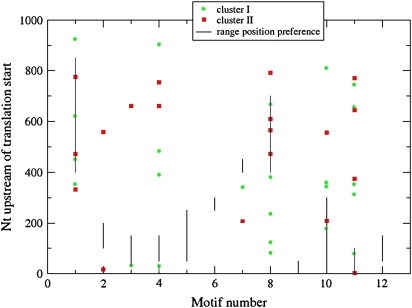

We searched for the presence of these novel motifs in 1 kb 5′ to the initiation codons of the P. falciparum rab genes to see if members of a given cluster had a specific association with motifs that might explain their expression profiles (Fig. 3). Both the presence and the position of the motifs are noted in green (cluster 1) and red (cluster 2). Some motifs are present more than once and motifs 5, 6, 9 and 12 [16] were not found in any rab upstream region. There appears to be no discernable association of a particular combination of motifs that is cluster specific (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

The presence and position of motifs [16] in 1 kb 5′ to the initiation codons of the P. falciparum rab genes is given for cluster 1 (green) and cluster 2 (red). Some motifs are present more than once and motifs 5, 6, 9 and 12 were not found in any rab upstream region.

Table 3.

Presence of regulatory elements in upstream regions of rab genes and effectors

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Max-exp | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFE0690c | Rab1A | 17 | 20 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 24 | |||||||

| PFB0500c | Rab5A | 12 | 16 | 17 | 12 | 15 | 25 | |||||||

| PFA0335w | Rab5C | 12 | 17 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 25 | |||||||

| PFE0765w | Vps34 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 30 | |||||||

| PFE0625w | Rab1B | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 30 | ||||||||

| PF11_0461 | Rab6 | 12 | 20 | 20 | 12 | 19 | 15 | 32 | ||||||

| MAL13P1.205 | Rab11B | 14 | 12 | 14 | 32 | |||||||||

| PF13_0057 | Rab5B | 12 | 19 | 16 | 12 | 16 | 14 | 37 | ||||||

| PFL1500w | Rab2 | 12 | 21 | 12 | 15 | 10 | ||||||||

| PF08_0110 | Rab18 | 12 | 21 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 9 | |||||||

| PF13_0119 | Rab11A | 12 | 15 | 12 | 14 | 25 | ||||||||

| PFI0155c | Rab7 | 14 | 18 | 15 | 11 | 15 | 30 |

Genes are ordered into cluster 1, cluster 2 and the left over cluster. Within the clusters the genes are ordered to the time of maximum level of mRNA expression for that gene. For each motif [16, p. 19], the highest score of the upstream region with that motif is given, together with the time after infection when that gene has maximum mRNA expression. For motif 4, a higher score seems to indicate earlier expression.

NB: Rab5c is expressed shortly before the Rab5 effector gene PFE0765w (vps34). If you take into account that the expression arrays of 10 and 45 h after infection PF14_0689 (Yip1p) is also close to rab2, but it would be synthesized first. Rab7 and MAL6P1.286 (PfMyoE) are both in the left over cluster and expressed shortly after each other. This is not true for PF10_0046 (Rabring 7).

6. Phylogenetic analysis indicated a core set of essential Rabs in Apicomplexa

In order to gain insights into what might constitute the minimal number of Rabs making up a core set for Apicomplexa we first established by repeated reciprocal BLAST analyses using P. falciparum Rabs as a query that T. annulata and T. parva code for a total of just 9 Rabs (see Table 1). The closely related Babesia has a similar number of 9 Rabs. Unlike Plasmodia parasites neither Theileria, nor Babesia encode Rab5B and Rab18. As stated, even though transcribed in P. falciparum Rab5B appears to be a non-functional Rab lacking a prenylation motif as its C-terminus [8]. Thus, its maintenance in both P. falciparum and P. berghei argues that Rab5B might play some novel regulatory function [11]. Importantly, Theileria and Babesia parasites differ from Plasmodia in that within host cells they do not reside inside a parasitophorous vacuole and the observation that they do not code for Rab18 may be related to the absence of the parasitophorous vacuole membrane, as a target membrane for vesicular transport.

We choose two other Apicomplexa, Toxoplasma and Cryptosporidia and asked if these related parasites posses Rab5B and Rab18 (Fig. 4). T. gondii was chosen, as like Plasmodia it resides within a parasitophorous vacuole and C. parvum and C. hominis, as they lack an apicoplast [1,25]. As we have previously remarked, similar Rabs from different Plasmodia parasites form clads with yeast Rabs (Ypts) suggesting potentially similar function [8,11]. Relevant here, is that the Rab5B clad only contains P. falciparum, P. berghei and T. gondii (Fig. 4). A Rab5B orthologue can also be detected in N. caninum (data not shown) arguing that any putative novel regulatory function performed by this unusual Rab might be common to Plasmodia and Toxoplasma/Neospora that reside within a parasitophorous vacuole.

Fig. 4.

An unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree showing the evolutionary relationships of amino acid sequences between the PM1 and PM3 domains [8] of Rab proteins from Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), Plasmodium berghei (Pb), Theileria parva (Tp), Theleria annulata (Ta), Babesia bovis (Bb), Cryptosporidium parvum (Cp), Cryptosporidium hominis (Ch), and Toxoplasma gondii (Tg). Bootstrap values are indicated on the branches. For a list of Rab sequences see Supplementary Fig. S2.

In plants Rab18 is induced by stress such as drought and its induction is thought to mobilise lipid food reserves [26]. In eukaryotes Rab18 is also associated with lipid droplets (LDs), which have been traditionally been considered relatively inert storage organelles [27]. Overexpression of Rab18 induces association of LDs with membrane cisternae connected to the rough ER [28]. The presence of Rab18 only in Plasmodia and Toxoplasma/Neospora could be taken as an indicator that Rab18 might be involved in mobilising parasite lipid reserves that will be used in the formation of the parasitophorous vacuole.

7. Discussion

Theileria parasites have just 9 Rabs, unlike Plasmodium, they do not have Rab5B and Rab18. We compared the Theileria Rab family to those of Babesia, Plasmodia, Toxoplasma and Cryptosporida to determine whether 9 represented the “core” set of minimal Rabs common to Apicomplexa (Fig. 4). Rabs have divergent N- and C-termini and as a consequence correct annotation of full-length Rabs sequences is often lacking in the different Apicomplexa databases and therefore, only circa 48 amino acids between the first two (PM1 and PM3) GTP-binding motifs [8] were used to construct the tree presented in Fig. 4. This revealed that Cryptosporidia with just 8 Rabs defines the smallest set of Rabs, while Toxoplasma with 15 (and Neospora, not shown) have the largest. Cryptosporidia differ from Theileria in lacking Rab5A and have only a single early endosome-specific Rab (Rab5C).

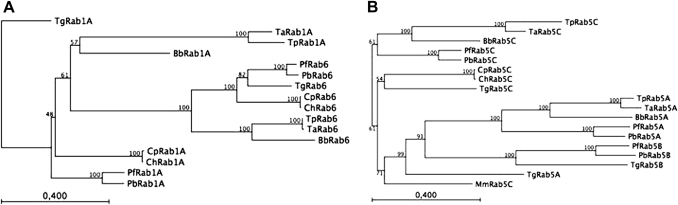

There are some notable features of the tree in Fig. 4. First, using just these “effector domain” amino acids between the PM1 and PM3 motifs [8], Rab1A from T. parva and T. annulata was found to cluster with Rab6, rather with Rab1A of the other Apicomplexa. Consequently, we repeated the phylogenic analysis with full-length Rab sequences for Rab1A, Rab6 and Rab11A for all 7 Apicomplexa (Fig. 5A). This shows that Rab1A from the two Theileria now clusters with the other Rab1As and particularly with Babesia, as expected. Due to the unusually long N-terminus of Rab1A from Toxoplasma (see Supplementary Fig. S4) it now appears as an outlier in this analysis and underscores why we used only amino acids between the PM1 and PM3 motifs in Fig. 5. Taken together, it would appear that Theileria posses an unusual Rab1A with a divergent, Rab6-like effector domain compared to Rab1As of the 6 other Apicomplexa.

Fig. 5.

A) An unrooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree showing the evolutionary relationships of full-length sequences of Rab1A, Rab6 and Rab11A from Plasmodium falciparum (Pf), Plasmodium berghei (Pb), Theileria parva (Tp), Theleria annulata (Ta), Babesia bovis (Bb), Cryptosporidium parvum (Cp), Cryptosporidium hominis (Ch), and Toxoplasma gondii (Tg). (B) A rooted neighbor-joining (NJ) tree showing the evolutionary relationships of full-length sequences of Apicomplexa Rab5A, Rab5B and Rab5C. The tree was rooted on Rab5C (GeneID: 19345) from Mus musculus (Mm). Bootstrap values are indicated on the branches. For full-length Rab1A sequences see Supplementary Fig. S3 and for full-length Rab5 sequences see Supplementary Fig. S4.

The second notable feature is the Rab5A clad with the long branch-lengths arguing that Rab5A is evolving faster than other Rabs of Apicomplexa (Fig. 4). You can note that this clad lacks Rab5A from Toxoplasma that appears in the Rab5C clad together with the Toxoplasma Rab5C orthologue. Individual BLAST analysis indicates that TgRab5A is almost similar to PfRab5A and PfRab5C. Taken as an ensemble the Rab5 clad (Rab 5A, 5B, 5C) is highly diverse and this divergence may be a reflection of adaptation of individual parasites to their specific intracellular environment (Fig. 5B). For example, Rab5A of Plasmodia is most unusual in having a 30 amino acid insertion in its effector domain and we have argued that this insertion could mediate interactions with novel Rab5 effector proteins [8,11]. This insertion is not observed in Rab5A of Theileria, Babesia and Toxoplasma strengthening the argument that any putative novel PfRab5A effectors are Plasmodia-specific. Plasmodia differ from Theileria, Babesia and Toxoplasma in that they import haemoglobin from infected erythrocytes (Babesia has no parasitophorous vacuole, nor is it known to degrade haemoglobin) and it is interesting to speculate that these putative novel Plasmodia Rab5A effectors might be involved in regulating uptake of haemoglobin.

The lack of Rab5B in Theileria might not be considered surprising given that this Rab seems to lack C-terminal geranyl-geranylation motifs [8]. Even though not attached to a vesicle, Rab5B is nonetheless expressed and probably binds some effector molecules and therefore, could play a regulatory function through sequestering these effectors into incompetent complexes. The maintenance of Rab5B in Toxoplasma that also lacks recognisable C-terminal geranyl-geranylation motifs argues that here also it is playing some unusual, perhaps similar, regulatory role. In the same vain, only Plasmodia and Toxoplasma/Neospora appear to have Rab18 (Fig. 5). We mentioned that Rab18 might be involved in mobilising parasite lipid reserves required for parasitophorous vacuole formation, but if so, it would argue that their parasitophorous vacuole differs from that of Crypstosporida and this indeed is the case [9].

The combined transcriptional profiling analysis of rab genes in Theileria (EST and MPSS profiling) and Plasmodia (microarray) concur and indicate that all Apicomplexa rab genes are transcribed all the time. MPSS scores in T. parva indicate that amounts of transcript for an individual rab, however, are generally low (10× lower than ran, see Table 2), but can vary for a given rab gene; for example, rab2 transcripts in T. parva are 60× more abundant than those for rab1a. To try and understand how parasites are controlling the levels of rab transcription we exploited the published P. falciparum microarray data and tried to correlate expression levels with the presence of a combination of specific motifs [16] in the 5′-regions 1 kb upstream of each P. falciparum rab gene (Figs. 2 and 3). We also asked if rabs with similar transcription profiles might have similar function, as suggested by their presence in the same cluster on the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). We could observe no obvious relationship between, expression profiles, a particular combination of promoter motifs and putative Rab function (Table 3).

There are a number of interesting concepts that stem from our analysis of rab gene expression, whether estimated by MPSS in T. parva, or microarray analysis in P. falciparum. Clearly, other factors such as mRNA stability may come into play and explain why some transcripts accumulate, while others do not. However, taken together, our analysis suggests that the structure of the “promoter” regions of rab genes may determine accessibility of the transcriptional machinery to the upstream regions of genes, i.e. the structure determines the level of chromatinisation and has a strong influence on transcription in Apicomplexan parasites. Low general levels of chromatinisation may explain why all (rab) genes are transcribed all the time and genes with readily accessible “promoters” are preferentially transcribed for the first few hours post-invasion.

Rabs in Apicomplexa thus provide insights not only into novel aspects of how intracellular protozoan parasites might regulate vesicular traffic, but also into (rab) gene transcription that may be controlled.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the Wellcome Trust for sponsoring part of the work described in the manuscript. The BBSRC for funding sequencing of the Neospora genome and ToxoDB and the sequencing centre (TIGR) that produced the Toxoplasma gondii sequence.

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2008.01.017.

Appendix. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Templeton T.J., Iyer L.M., Anantharaman V., Enomoto S., Abrahante J.E., Subramanian G.M., Hoffman S.L., Abrahamsen M.S., Aravind L. Comparative analysis of apicomplexa and genomic diversity in eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2004;14:1686–1695. doi: 10.1101/gr.2615304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle J.P., Saeij J.P., Cleary M.D., Boothroyd J.C. Analysis of gene expression during development: lessons from the Apicomplexa. Microb. Infect. 2006;8:1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bozdech Z., Llinas M., Pulliam B.L., Wong E.D., Zhu J., DeRisi J.L. The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bozdech Z., Zhu J., Joachimiak M.P., Cohen F.E., Pulliam B., DeRisi J.L. Expression profiling of the schizont and trophozoite stages of Plasmodium falciparum with a long-oligonucleotide microarray. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-2-r9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brayton K.A., Lau A.O., Herndon D.R., Hannick L., Kappmeyer L.S., Berens S.J., Bidwell S.L., Brown W.C., Crabtree J., Fadrosh D., Feldblum T., Forberger H.A., Haas B.J., Howell J.M., Khouri H., Koo H., Mann D.J., Norimine J., Paulsen I.T., Radune D., Ren Q., Smith R.K., Jr., Suarez C.E., White O., Wortman J.R., Knowles D.P., Jr., McElwain T.F., Nene V.M. Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1401–1413. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosshans B.L., Ortiz D., Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:11821–11827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pain A., Renauld H., Berriman M., Murphy L., Yeats C.A., Weir W., Kerhornou A., Aslett M., Bishop R., Bouchier C., Cochet M., Coulson R.M., Cronin A., de Villiers E.P., Fraser A., Fosker N., Gardner M., Goble A., Griffiths-Jones S., Harris D.E., Katzer F., Larke N., Lord A., Maser P., McKellar S., Mooney P., Morton F., Nene V., O'Neil S., Price C., Quail M.A., Rabbinowitsch E., Rawlings N.D., Rutter S., Saunders D., Seeger K., Shah T., Squares R., Squares S., Tivey A., Walker A.R., Woodward J., Dobbelaere D.A., Langsley G., Rajandream M.A., McKeever D., Shiels B., Tait A., Barrell B., Hall N. Genome of the host-cell transforming parasite Theileria annulata compared with T. parva. Science. 2005;309:131–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1110418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quevillon E., Spielmann T., Brahimi K., Chattopadhyay D., Yeramian E., Langsley G. The Plasmodium falciparum family of Rab GTPases. Gene. 2003;306:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyer T.V., Svezhova N.V., Radchenko A.I., Sidorenko N.V. Parasitophorous vacuole: morphofunctional diversity in different coccidian genera (a short insight into the problem) Cell Biol. Int. 2002;26:861–871. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2002.0943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haldar K., Mohandas N., Samuel B.U., Harrison T., Hiller N.L., Akompong T., Cheresh P. Protein and lipid trafficking induced in erythrocytes infected by malaria parasites. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:383–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baunaure F., Langsley G. Protein traffic in Plasmodium infected-red blood cells. Med. Sci. (Paris) 2005;21:523–529. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2005215523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ralph S.A., Foth B.J., Hall N., McFadden G.I. Evolutionary pressures on apicoplast transit peptides. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:2183–2194. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben Mamoun C., Gluzman I.Y., Hott C., MacMillan S.K., Amarakone A.S., Anderson D.L., Carlton J.M., Dame J.B., Chakrabarti D., Martin R.K., Brownstein B.H., Goldberg D.E. Co-ordinated programme of gene expression during asexual intraerythrocytic development of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum revealed by microarray analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;39:26–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roch K.G., Zhou Y., Batalov S., Winzeler E.A. Monitoring the chromosome 2 intraerythrocytic transcriptome of Plasmodium falciparum using oligonucleotide arrays. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002;67:233–243. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop R., Shah T., Pelle R., Hoyle D., Pearson T., Haines L., Brass A., Hulme H., Graham S.P., Taracha E.L., Kanga S., Lu C., Hass B., Wortman J., White O., Gardner M.J., Nene V., de Villiers E.P. Analysis of the transcriptome of the protozoan Theileria parva using MPSS reveals that the majority of genes are transcriptionally active in the schizont stage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5503–5511. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Noort V., Huynen M.A. Combinatorial gene regulation in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Genet. 2006;22:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aravind L., Iyer L.M., Wellems T.E., Miller L.H. Plasmodium biology: genomic gleanings. Cell. 2003;115:771–785. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janoo R., Musoke A., Wells C., Bishop R. A Rab1 homologue with a novel isoprenylation signal provides insight into the secretory pathway of Theileria parva. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999;102:131–143. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunasekera A.M., Patankar S., Schug J., Eisen G., Kissinger J., Roos D., Wirth D.F. Widespread distribution of antisense transcripts in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004;136:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patankar S., Munasinghe A., Shoaibi A., Cummings L.M., Wirth D.F. Serial analysis of gene expression in Plasmodium falciparum reveals the global expression profile of erythrocytic stages and the presence of anti-sense transcripts in the malarial parasite. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:3114–3125. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langsley G., Sibilli L., Mattei D., Falanga P., Mercereau-Puijalon O. Karyotype comparison between P. chabaudi and P. falciparum: analysis of a P. chabaudi cDNA containing sequences highly repetitive in P. falciparum. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:2203–2211. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.5.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wellems T.E., Walliker D., Smith C.L., do Rosario V.E., Maloy W.L., Howard R.J., Carter R., McCutchan T.F. A histidine-rich protein gene marks a linkage group favored strongly in a genetic cross of Plasmodium falciparum. Cell. 1987;49:633–642. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin H.W., Hayashi M., Christoforidis S., Lacas-Gervais S., Hoepfner S., Wenk M.R., Modregger J., Uttenweiler-Joseph S., Wilm M., Nystuen A., Frankel W.N., Solimena M., De Camilli P., Zerial M. An enzymatic cascade of Rab5 effectors regulates phosphoinositide turnover in the endocytic pathway. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:607–618. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Roch K.G., Zhou Y., Blair P.L., Grainger M., Moch J.K., Haynes J.D., De La Vega P., Holder A.A., Batalov S., Carucci D.J., Winzeler E.A. Discovery of gene function by expression profiling of the malaria parasite life cycle. Science. 2003;301:1503–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.1087025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ralph S.A., van Dooren G.G., Waller R.F., Crawford M.J., Fraunholz M.J., Foth B.J., Tonkin C.J., Roos D.S., McFadden G.I. Tropical infectious diseases: metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:203–216. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karim S., Aronsson H., Ericson H., Pirhonen M., Leyman B., Welin B., Mantyla E., Palva E.T., Van Dijck P., Holmstrom K.O. Improved drought tolerance without undesired side effects in transgenic plants producing trehalose. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;64:371–386. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin S., Driessen K., Nixon S.J., Zerial M., Parton R.G. Regulated localization of Rab18 to lipid droplets: effects of lipolytic stimulation and inhibition of lipid droplet catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:42325–42335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozeki S., Cheng J., Tauchi-Sato K., Hatano N., Taniguchi H., Fujimoto T. Rab18 localizes to lipid droplets and induces their close apposition to the endoplasmic reticulum-derived membrane. J. Cell. Sci. 2005;118:2601–2611. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.