Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus belongs to the Gram-positive low G + C content group of the Firmicutes division of bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus is an important human and veterinary pathogen that causes a broad spectrum of diseases, and has developed important multidrug resistant forms such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Staphylococcus simiae was isolated from South American squirrel monkeys in 2000, and is a coagulase-negative bacterium, closely related, and possibly the sister group, to S. aureus. Comparative genomic analyses of closely related bacteria with different phenotypes can provide information relevant to understanding adaptation to host environment and mechanisms of pathogenicity.

Results

We determined a Roche/454 draft genome sequence for S. simiae and included it in comparative genomic analyses with 11 other Staphylococcus species including S. aureus. A genome based phylogeny of the genus confirms that S. simiae is the sister group to S. aureus and indicates that the most basal Staphylococcus lineage is Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, followed by Staphylococcus carnosus. Given the primary niche of these two latter taxa, compared to the other species in the genus, this phylogeny suggests that human adaptation evolved after the split of S. carnosus. The two coagulase-positive species (S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius) are not phylogenetically closest but share many virulence factors exclusively, suggesting that these genes were acquired by horizontal transfer. Enrichment in genes related to mobile elements such as prophage in S. aureus relative to S. simiae suggests that pathogenesis in the S. aureus group has developed by gene gain through horizontal transfer, after the split of S. aureus and S. simiae from their common ancestor.

Conclusions

Comparative genomic analyses across 12 Staphylococcus species provide hypotheses about lineages in which human adaptation has taken place and contributions of horizontal transfer in pathogenesis.

Background

Staphylococcus belongs to the Gram-positive low G + C content group of the Firmicutes division of bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus is an important human and veterinary pathogen that causes a broad spectrum of diseases, and has developed important multidrug resistant forms such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) [1-3]. Despite emergence of MRSA in human and various animal species, mechanisms of host adaptation are poorly understood [4]. Comparative genomic analyses of phylogenetically closely related bacteria with different phenotypes (e.g. host specificity and pathogenicity) can provide information relevant to understanding adaptation to host environment and mechanisms of pathogenicity [5-10]. Staphylococcus simiae was isolated from South American squirrel monkeys in 2000, and is a coagulase-negative bacterium closely related, and indeed possibly the sister group, to S. aureus [11]. Comparison between S. aureus and S. simiae genomes could provide valuable information regarding host adaptation and pathogenesis. Thus, we determined a draft genome sequence of S. simiae type strain CCM 7213T (= LMG 22723T), and included it in comparative genomic analyses with 11 other Staphylococcus species.

Methods

Genome sequencing and data collation

We determined the genome sequence of Staphylococcus simiae type strain CCM 7213T (= LMG 22723T), isolated from the faeces of a South American squirrel monkey [11]. Roche/454 pyrosequencing, involving a single full run of the GS-20 sequencer, was used to determine the sequence of the Staphylococcus simiae genome. The sequences were assembled (De novo assembly with Newbler Software) into 565 contigs. Genome annotation for the strain was done by the NCBI Prokaryotic Genomes Automatic Annotation Pipeline. The S. simiae whole genome shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession AEUN00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version, AEUN01000000. For comparative analysis genome sequences of bacteria in GenBank format [12] were retrieved from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) site ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. We analyzed sequences of 28 Staphylococcus strains belonging to 12 different species, and an outgroup Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402 [13] (Table 1 and Additional file 1, Table S1). The 16 Staphylococcus aureus strains included COL [14], ED133 [15], ED98 [16], JH1, JH9, MRSA252 [17], MSSA476 [17], Mu3 [18], Mu50 [19], MW2 [20], N315 [19], NCTC_8325, Newman [21], RF122/ET3-1 [22], USA300_FPR3757 [23], and USA300_TCH1516 [24]. The remaining 12 Staphylococcus strains included Staphylococcus capitis SK14 [25], Staphylococcus caprae C87, Staphylococcus carnosus TM300 [26], Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228 [27], Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62a [14], Staphylococcus haemolyticus JCSC1435 [28], Staphylococcus hominis SK119, Staphylococcus lugdunensis HKU09-01 [29], Staphylococcus pseudintermedius HKU10-03 [30], Staphylococcus saprophyticus ATCC_15305 [31], Staphylococcus simiae [11], and Staphylococcus warneri L37603. Genome sequence analyses were implemented using Bioperl version 1.6.1 [32] and G-language Genome Analysis Environment version 1.8.12 [33-35]. Statistical tests and graphics were implemented using R, version 2.11.1 [36].

Table 1.

Genomic features of Macrococcus caseolyticus and 28 Staphylococcus strains.

| Organism | Size (bp) | %G + C | S | No.CDS | No.MCL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSC5402 | 2219737 | 36.6 | 1.27 | 2052 | 1688 |

| Staphylococcus aureus COL | 2813862 | 32.8 | 1.58 | 2615 | 2304 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ED133 | 2832478 | 32.9 | 1.55 | 2653 | 2291 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ED98 | 2847542 | 32.8 | 1.56 | 2689 | 2338 |

| Staphylococcus aureus JH1 | 2936936 | 32.9 | 1.40 | 2780 | 2389 |

| Staphylococcus aureus JH9 | 2937129 | 32.9 | 1.40 | 2726 | 2389 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MRSA252 | 2902619 | 32.8 | 1.57 | 2650 | 2353 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MSSA476 | 2820454 | 32.8 | 1.57 | 2590 | 2330 |

| Staphylococcus aureus Mu3 | 2880168 | 32.9 | 1.54 | 2690 | 2368 |

| Staphylococcus aureus Mu50 | 2903636 | 32.8 | 1.54 | 2730 | 2389 |

| Staphylococcus aureus MW2 | 2820462 | 32.8 | 1.58 | 2624 | 2319 |

| Staphylococcus aureus N315 | 2839469 | 32.8 | 1.55 | 2614 | 2307 |

| Staphylococcus aureus NCTC_8325 | 2821361 | 32.9 | 1.56 | 2891 | 2347 |

| Staphylococcus aureus Newman | 2878897 | 32.9 | 1.54 | 2614 | 2338 |

| Staphylococcus aureus RF122 | 2742531 | 32.8 | 1.55 | 2509 | 2267 |

| Staphylococcus aureus USA300_FPR3757 | 2917469 | 32.7 | 1.58 | 2604 | 2385 |

| Staphylococcus aureus USA300_TCH1516 | 2903081 | 32.7 | 1.56 | 2689 | 2382 |

| Staphylococcus capitis SK14 | 2435835 | 32.8 | 1.47 | 2230 | 1847 |

| Staphylococcus caprae C87 | 2473608 | 32.6 | 1.46 | 2402 | 1887 |

| Staphylococcus carnosus TM300 | 2566424 | 34.6 | 1.42 | 2461 | 1859 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC_12228 | 2564615 | 32.0 | 1.12 | 2482 | 1972 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A | 2643840 | 32.1 | 1.15 | 2525 | 2068 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus JCSC1435 | 2697861 | 32.8 | 1.42 | 2692 | 2021 |

| Staphylococcus hominis SK119 | 2226236 | 31.3 | 1.53 | 2182 | 1729 |

| Staphylococcus lugdunensis HKU09-01 | 2658366 | 33.9 | 1.26 | 2490 | 1896 |

| Staphylococcus pseudintermedius HKU10-03 | 2617381 | 37.5 | 1.50 | 2450 | 1910 |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus ATCC_15305 | 2577899 | 33.2 | 1.34 | 2514 | 1838 |

| Staphylococcus simiae CCM_7213 | 2587121 | 31.9 | 1.33 | 2592 | 1950 |

| Staphylococcus warneri L37603 | 2425653 | 32.8 | 1.42 | 2381 | 1875 |

%G + C = 100 × (G + C)/(A + T + G + C).

S = Selected codon usage bias.

No.CDS = Number of protein-coding sequences.

No.MCL = Number of protein families built by BLAST and Markov clustering.

Gene content analysis

Protein-coding sequences were retrieved from chromosomes and plasmids of the 29 strains of bacteria (Table 1 and Additional file 1 Table S1). A group of homologous proteins (protein family) was built by all-against-all protein sequence comparison of the 29 strains' proteomes using BLASTP [37], followed by Markov clustering (MCL) with an inflation factor of 1.2 [38]. Homologous proteins were identified by BLASTP on the criteria of an E-value cutoff of 1e-5, and minimum aligned sequence length coverage of 50% of a query sequence. This approach yielded 5014 protein families containing 74122 individual proteins from the 29 strains (see Additional file 1, Table S2). We assigned functions to each protein family by using multiple databases: the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) [39,40], JCVI [41], KEGG [42], SEED [43], Virulence Factors Database (VFDB) [44], MvirDB [45], Pfam [46], and Gene Ontology (GO) [47] database. We searched protein sequences against the Pfam library of hidden Markov models (HMMs) using HMMER http://hmmer.janelia.org/, and converted Pfam accession numbers to GO terms using the 'pfam2go' mapping http://www.geneontology.org/external2go/pfam2go. We performed TBLASTN searches (on the criteria of an E-value cutoff of 1e-5, and minimum aligned sequence length coverage of 50% of a query sequence) of each of the 29 strains' proteomes against whole nucleotide sequences of all the other strains to avoid artefacts caused by differences in protein-coding sequence prediction [8,48]. The resulting gene content (binary data for presence or absence of each protein family) is shown in Additional file 1, Table S2.

Hierarchical clustering (UPGMA) of the 29 strains was performed using a distance between two genomes based on gene content (binary data for presence or absence of each protein family) measured by one minus the Jaccard coefficient (Jaccard distance). To identify taxon-specific genes, we calculated Cramer's V to screen protein families showing biased distributions between comparative groups. Cramer's V is a measure of the degree of correlation in contingency tables. Cramer's V values close to 0 indicate weak associations between variables, while those close to 1 indicate strong associations. We used the most stringent threshold (i.e. Cramer's V of 1) to identify S. aureus and S. simiae unique proteins or protein families. To examine over- or underrepresented functional categories in the 16 S. aureus strains relative to the single S. simiae strain, a 2 × 2 contingency table was constructed for each functional category from the COG, JCVI, KEGG, SEED, VFDB, and GO databases: (a) the number of S. aureus protein families in this category; (b) the number of S. aureus protein families not in this category; (c) the number of S. simiae protein families in this category; and (d) the number of S. simiae protein families not in this category. The odds ratio (= ad/bc) was used to rank the relative over-representation (> 1) or under-representation (< 1) of each of the functional categories.

Phylogenetic analysis

Of the 5014 protein families, 497 were shared by all the 29 strains and contained only a single copy from each strain (did not contain paralogs). This set of 497 single-copy core genes were identified as putative orthologous genes. The sequences were first aligned at the amino acid level using Probalign [49], then backtranslated to DNA. Alignment columns with a posterior probability < 0.6 were removed, and alignments with > 50% of the sites removed were discarded from the analysis. Multiple alignments with Probalign retained 491 reliably aligned genes from a set of the 497 orthologous genes. Gene trees were reconstructed using PhyML (Phylogenetic estimation using Maximum Likelihood) [50,51] with the General Time Reversible plus Gamma (GTR + G) substitution model of DNA evolution, and the Subtree Pruning-Regrafting (SPR) branch-swapping method. Each gene tree search was bootstrapped (500 pseudoreplicates) using PhyML with the Nearest-Neighbor Interchange (NNI) branch-swapping method to detect genes that support or conflict with various bipartitions. A majority rule consensus of the gene trees was constructed using the consense program of PHYLIP 3.69 [52]. All the alignments were also concatenated, and a tree search was performed using PhyML with the same settings as for the gene trees. Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402 was used as an outgroup to root the trees. We used DendroPy [53] to annotate the nodes of the estimated consensus and concatenated gene trees with the percentage of gene trees in which the node was found. Resulting phylogenetic trees were drawn using the R package APE (Analysis of Phylogenetics and Evolution) [54].

Results and discussion

Genomic features

Roche/454 pyrosequencing was used to determine the sequence of the Staphylococcus simiae genome. A total of 643168 single-end reads resulted from the GS-20 sequencer for S. simiae. De novo assembly with Newbler yielded 565 contigs for a total genome size of 2,587,121 bp with G + C content of 31.9% and 2592 protein-coding sequences (Table 1) with sequencing coverage of 27.4 (2623 singleton reads). The N50 size of the contigs is 19200.

Genome size was larger in S. aureus (ranging from to 2.743 Mbp to 2.937 Mbp) than in the other Staphylococcus species (ranging from to 2.220 Mbp to 2.698 Mbp). Genomic G + C content of M. caseolyticus (36.6%), S. pseudintermedius (37.5%), and S. carnosus (34.6%) were higher than those of the other Staphylococcus species (ranging from to 31.3% to 33.9%). Genomic G + C content is a result of mutation and selection [55], involving multiple factors including environment [56], symbiotic lifestyle [57], aerobiosis [58], and nitrogen fixation ability [59]. Bacteria showing evidence of translational selection on synonymous codon usage of highly expressed genes tend to have more rRNA operons, more tRNA genes, and faster growth rate [60]. The strength of translationally selected codon usage bias (S) [60] was significantly higher in S. aureus (median S = 1.56) than in the other Staphylococcus species (median S = 1.42) based on Mann-Whitney test (P < 10-4); S. epidermidis strains RP62A (S = 1.15) and ATCC_12228 (S = 1.12) showed the lowest values of S (Table 1).

Phylogeny

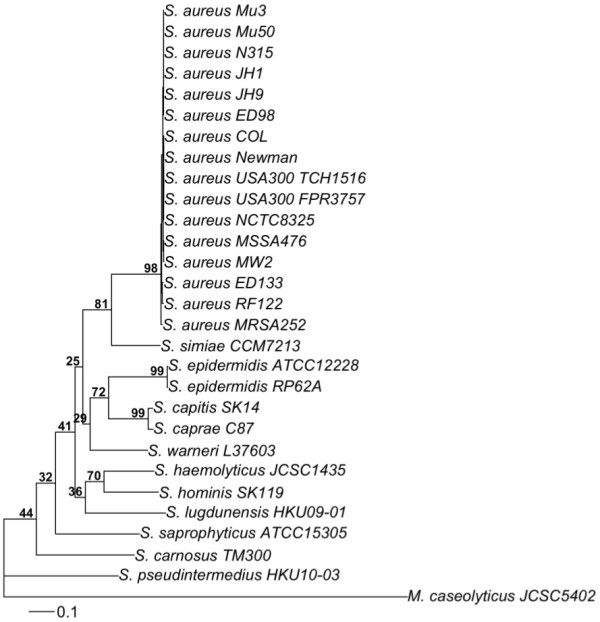

The 491 orthologous genes were used to infer phylogenetic relationships of the 28 Staphylococcus strains. The phylogenetic tree inferred from concatenated genes (Figure 1), as well as the majority rule consensus of the individual gene trees (Additional file 2, Figure S1) demonstrated that the vast majority of genes supported the monophyly of the 16 S. aureus strains (98%), the monophyly of the two S. epidermidis strains (99%), and the monophyly of the clade of S. aureus and S. simiae (81%), supporting previous suggestions that S. simiae is the putative sister group to S. aureus [11]. Of the 491 gene trees, 486, 491, and 322 (99%, 100%, and 65.6%) supported these three nodes with bootstrap support in excess of 70%, and none had a strongly supported conflicting signal compared to that topology.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree inferred from concatenated genes. Maximum likelihood tree obtained from a concatenated nucleotide sequence alignment of the orthologous core genes for the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402 (outgroup). The horizontal bar at the base of the figure represents 0.1 substitutions per nucleotide site. The percentages of genes that support the branches of the tree are indicated.

The most basal Staphylococcus lineage in our phylogenetic trees was S. pseudintermedius, followed by S. carnosus. Although support for these two nodes involved only 217 and 156 (44% and 32%) of the 491 gene trees, there were only a few instances of genes that had a strongly supported conflicting signal compared to that topology. Only 37 and 17 (7.5% and 3.5%) of the 491 genes had a conflicting evolutionary history for these two nodes with bootstrap support in excess of 70%, while 107 and 56 (21.8% and 11.4%) supported these two nodes with bootstrap support in excess of 70%. Staphylococcus species which are indigenous to humans include S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. caprae, S. capitis, S. warneri, S. hominis, S. haemolyticus, S. lugdunensis, and S. saprophyticus [61]. S. carnosus has not been isolated from human skin or mucosa, and its natural habitat is unknown despite its natural occurrence in meat and fish products [26]. S. pseudintermedius is a coagulase-positive species from animals [62], and M. caseolyticus is typically isolated from animal skin and food such as milk and meat [13]. Although species indigenous to animals may be found occasionally on humans by recent contact [61,63], our phylogeny suggests that human adaptation evolved after the split of S. carnosus.

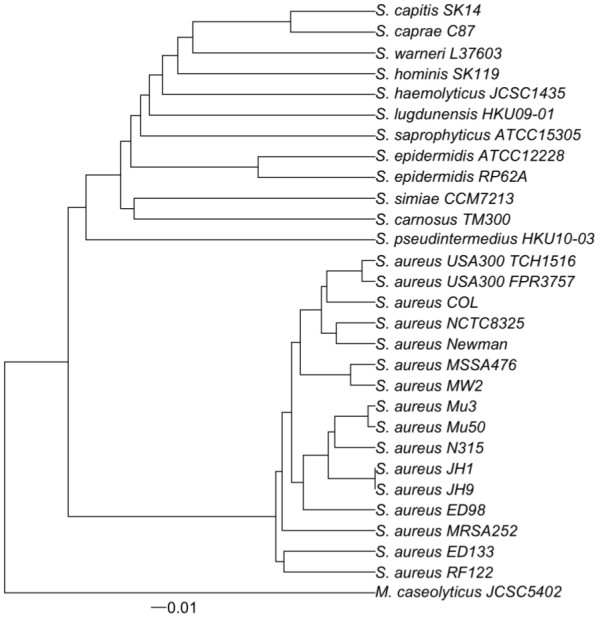

Gene content

The 69171 protein-coding sequences from the 29 strains were classified into 5361 homolgous groups or protein families (see Additional file 1, Table S2). A dendrogram constructed by hierarchical clustering (Figure 2) indicates that the overall similarity of the 29 strains based on gene content (binary data for presence or absence of different protein families) did not strictly follow their phylogenetic history (Figure 1 and Additional file 2, Figure S1). This indicates that the Staphylococcus gene repertoire reflects not only vertical inheritance of genes, but probable instances of one or more of the following: lineage-specific gene loss, non-orthologous gene displacement, or gene gain through horizontal gene transfer [64].

Figure 2.

Gene content dendrogram. A dendrogram constructed by hierarchical clustering based on dissimilarities in gene content (binary data for presence or absence of protein families) for the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402. The dissimilarities were measured using the Jaccard distance, ranging from 0 to 1, represented by the horizontal bar at the base of the figure.

We assessed presence of virulence factors in the Staphylococcus strains based on the gene content table (Additional file 1, Table S2) and percent identity values of TBLASTN best hits against VFDB (Additional file 3, Figure S2). Many virulence genes of S. aureus are encoded on mobile genetic elements such as staphylococcal cassette chromosomes (SCC), genomic islands, pathogenicity islands, prophages, plasmids, insertion sequences, and transposons [2,3,65]. For movement, SCC carries cassette chromosome recombinase (ccr) gene(s) (ccrAB or ccrC) [66,67]. The three ccr genes (ccrA, ccrB, and ccrC) are homologous and have no homolog in S. carnosus. The genetic determinant of methicillin resistance (mec) is encoded on SCC in S. aureus, designated as SCCmec [68]. Expression of beta-lactamase (blaZ) and penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP 2a) genes (mecA) is controlled by the BlaR-BlaI-BlaZ and MecR-MecI-MecA regulatory systems, respectively [69]. There is homology between blaI and mecI, between blaR1 and mecR1, and between the promoter and N-terminal portions of blaZ and mecA [70]. mecA gene homologs were present in all Staphylococcus species, while presence of blaI/mecI and blaR1/mecR1 gene homologs varied among different Staphylococcus species and even between different strains within S. aureus. S. aureus genomic islands and pathogenicity islands carry superantigenic toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) encoded by tst [71] homologous to the staphylococcal exotoxin-like (set) proteins, renamed staphylococcal superantigen-like (ssl) proteins. The tst gene homolog was present in S. carnosus TM300 (Sca_0436 and Sca_0905) and S. pseudintermedius HKU10-03 (SPSINT_0099). A previous study [26] reported that S. carnosus TM300 lacks the known superantigens such as toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (tst) and enterotoxins (sea to sep). The serine protease (spl) gene homolog was not found in S. lugdunensis. Lipoprotein (lpl) gene homologs were present in S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, and S. lugdunensis. S. aureus prophages carry virulence factors such as Panton-Valentine leukocidin (lukS-PV and lukF-PV), staphylokinase (sak), exfoliative toxin A (eta), and enterotoxins [72]. The sak gene homolog was present in the 12 S. aureus strains but absent in the 4 S. aureus strains (COL, ED133, ED98, and RF122). The eta gene homolog was present in S. aureus, S. carnosus TM300 (Sca_2302), and S. pseudintermedius HKU10-03 (SPSINT_0069). S. aureus can produce several homologous two-component pore-forming toxins including Panton-Valentine leukocidin (lukS-PV and lukF-PV on prophage), leukotoxin D and E (lukD and lukE on genomic island), and gamma-hemolysin (hlgA, hlgB, and hlgC) [73,74], with homologs present in S. pseudintermedius HKU10-03 (SPSINT_1566 and SPSINT_1567). Staphylococcal enterotoxins (entD, entE, sea, seb, sec1, sec3, sed, seg2, seh, and sek2) encoded on S. aureus mobile genetic elements [2] were homologous and have a single homolog in S. pseudintermedius HKU10-03 (SPSINT_0513). As expected, a secreted von Willebrand factor-binding protein (coagulase) [75] was present in the coagulase-positive staphylococci (S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius) but absent in the coagulase-negative staphylococci [76].

To identify S. aureus and S. simiae unique genes, we compared gene presence and absence between the 16 S. aureus strains and the other 12 Staphylococcus strains, and between the single S. simiae strain and the other 27 Staphylococcus strains. A total of 272 protein families were present in S. aureus but absent in the other Staphylococcus species (Additional file 1, Table S3). This set included known as well as candidate virulence factors of S. aureus such as staphylococcal complement inhibitor SCIN (fibrinogen-binding protein), hyaluronate lyase (hysA), GntR family transcriptional regulator, secretory extracellular matrix and plasma binding protein, isdD (Iron uptake; Heme uptake), zinc finger SWIM domain-containing protein, 1-phosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase known as a virulence factor (Exoenzyme; Membrane-damaging; Phospholipase) of Listeria monocytogenes (serovar 1/2a) EGD-e, formyl peptide receptor-like 1 inhibitory protein, NADH dehydrogenase subunit, 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase, probable exported proteins and membrane proteins. Genes encoding quaternary ammonium compound-resistance protein SugE were absent in S. aureus but present in the other Staphylococcus species. It was previously shown that high-level expression of SugE of Escherichia coli leads to resistance to a subset of toxic quaternary ammonium compounds [77]. A total of 129 unique protein families were present in S. simiae but absent in other Staphylococcus species (Additional file 1, Table S4). This set included surface anchored protein, DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase II, reverse transcriptase, transcriptional regulators, and phage-related proteins. The S. aureus and S. simiae unique genes may have been gained on the branch leading to the S. aureus ancestor and the S. simiae strain, and could be linked to their specific host adaptation and pathogenesis. Many of these genes were, however, quite short (< 150 bp) and functionally unknown, and thus could be protein-coding sequence prediction error.

Enrichment tests across functional categories indicated that the JCVI mainrole categories "Cell envelope" (odds ratio = 1.15) and "Mobile and extrachromosomal element functions" (odds ratio = 1.38), the JCVI subrole categories "Pathogenesis" (odds ratio = 1.40) and "Prophage functions" (odds ratio = 1.38), the KEGG pathway map "Staphylococcus aureus infection" (odds ratio = 1.91), and the VFDB keyword "Type VII secretion system" (odds ratio = 7.06) were overrepresented in S. aureus relative to S. simiae (Additional file 1, Table S5). None of the functional categories were significantly over- or underrepresented based on Fisher's exact test after false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons (P < 0.05). A total of 52 protein families associated with cell envelope were identified here, and the numbers were higher in S. aureus (ranging from 48 to 50) than in other Staphylococcus species (ranging from 33 to 45). Cell wall-associated proteins are involved in host-pathogen interactions, and those from S. aureus ED133 have been shown to be under diversifying selection pressure [15]. A total of 79 protein families associated with cell wall were identified here, and the numbers were higher in S. aureus (ranging from 60 to 64) than in other Staphylococcus species (ranging from 47 to 60). A cluster of eight genes, esxA, esaA, essA, essB, esaB, essC, esaC, and esxB, related to type VII secretion system [78] was present in the 15 S. aureus strains. Of the eight genes, esxA, esaA, essA, essB, esaB, and essC were present but esaC and esxB were absent in S. aureus MRSA252 and S. lugdunensis HKU09-01. S. aureus is known to carry a variety of mobile genetic elements such as prophages, plasmids, and transposons [2,72]. A total of 302, 166, and 27 protein families associated with phage, plasmid, and transposase were identified here. The numbers of protein families annotated as phage, plasmid, and transposase in S. simiae were 126, 75, and 13, whereas the numbers present in genomes of S. aureus ranged from 130-195, 84-124, and 11-20. This ranks S. aureus among the top of Staphylococcus genomes in terms of abundance of genes related to mobile genetic elements. Our results suggest that pathogenesis in the S. aureus group has developed by gene gain through horizontal transfer of mobile genetic elements, after divergence of S. simiae and S. aureus from their common ancestor.

Authors' contributions

HS carried out the bioinformatics analyses, and wrote the manuscript. TL participated in the bioinformatics analyses. PPB performed the laboratory experiments. MJS conceived the study and helped write the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Genomic information of the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402. Supplementary Table S2. Gene content table for the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402. The first 13 columns contain the protein family identification number, partial sequence (0, no; 1, one side; 2, both sides), amino acid length (Laa), locus_tag or protein_id (tag), functional annotations from different databases: COG, GenBank, JCVI, KEGG, VFDB, MvirDB, Pfam, and GO. The remaining columns show binary data (1 or 0) for presence or absence of each protein family for each of the 29 strains. Supplementary Table S3. Protein families present in Staphylococcus aureus and absent in other Staphylococcus species, and vice versa. The first 13 columns are explained in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Table S4. Protein families present in Staphylococcus simiae and absent in other Staphylococcus species, and vice versa. The first 13 columns are explained in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Table S5. Database categories that are over- or underrepresented in Staphylococcus aureus relative to Staphylococcus simiae. a = the number of the S. aureus strains' protein families in this category, b = the number of the S. aureus strains' protein families not in this category, c = the number of the S. simiae strain's protein families in this category, d = the number of the S. simiae strain's protein families not in this category, odds ratio = ad/bc, p-value obtained by Fisher's exact test, and q-value (false discovery rate adjusted p-value).

Supplementary Figure S1. A majority rule consensus of the maximum likelihood trees obtained from nucleotide sequences of the orthologous core genes for the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402 (outgroup). The percentages of genes that support the branches of the tree are indicated.

Supplementary Figure S2. A heatmap showing % identity values of TBLASTN (E-value cutoff of 1e-5) best hits in the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402, against Staphylococcus virulence genes deposited in Virulence Factors Database (VFDB).

Contributor Information

Haruo Suzuki, Email: hs568@cornell.edu.

Tristan Lefébure, Email: tristan.lefebure@univ-lyon1.fr.

Paulina Pavinski Bitar, Email: pdm37@cornell.edu.

Michael J Stanhope, Email: mjs297@cornell.edu.

Acknowledgements

We thank Vincent P. Richards for helpful discussion, and Robert Bukowski for his help with the parallelization of the analyses on a Linux cluster at the Computational Biology Service Unit of Cornell University. This work was supported by Cornell University start-up funds and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, US National Institutes of Health, under grant number R01AI073368 awarded to M.J.S.

References

- Gould IM. VRSA-doomsday superbug or damp squib? Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(12):816–818. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malachowa N, DeLeo FR. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67(18):3057–3071. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plata K, Rosato AE, Wegrzyn G. Staphylococcus aureus as an infectious agent: overview of biochemistry and molecular genetics of its pathogenicity. Acta Biochim Pol. 2009;56(4):597–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuny C, Friedrich A, Kozytska S, Layer F, Nubel U, Ohlsen K, Strommenger B, Walther B, Wieler L, Witte W. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in different animal species. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300(2-3):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebure T, Stanhope MJ. Evolution of the core and pan-genome of Streptococcus: positive selection, recombination, and genome composition. Genome Biol. 2007;8(5):R71. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebure T, Stanhope MJ. Pervasive, genome-wide positive selection leading to functional divergence in the bacterial genus Campylobacter. Genome Res. 2009;19(7):1224–1232. doi: 10.1101/gr.089250.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SL, Hung CS, Xu J, Reigstad CS, Magrini V, Sabo A, Blasiar D, Bieri T, Meyer RR, Ozersky P. et al. Identification of genes subject to positive selection in uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli: a comparative genomics approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(15):5977–5982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y, Ooka T, Iguchi A, Toh H, Asadulghani M, Oshima K, Kodama T, Abe H, Nakayama K, Kurokawa K. et al. Comparative genomics reveal the mechanism of the parallel evolution of O157 and non-O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(42):17939–17944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903585106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi RH, Sun Q, Wiedmann M. Genome-wide analyses reveal lineage specific contributions of positive selection and recombination to the evolution of Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soyer Y, Orsi RH, Rodriguez-Rivera LD, Sun Q, Wiedmann M. Genome wide evolutionary analyses reveal serotype specific patterns of positive selection in selected Salmonella serotypes. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9:264. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantucek R, Sedlacek I, Petras P, Koukalova D, Svec P, Stetina V, Vancanneyt M, Chrastinova L, Vokurkova J, Ruzickova V. et al. Staphylococcus simiae sp. nov., isolated from South American squirrel monkeys. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55(Pt 5):1953–1958. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011. pp. D32–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baba T, Kuwahara-Arai K, Uchiyama I, Takeuchi F, Ito T, Hiramatsu K. Complete genome sequence of Macrococcus caseolyticus strain JCSCS5402, [corrected] reflecting the ancestral genome of the human-pathogenic staphylococci. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(4):1180–1190. doi: 10.1128/JB.01058-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SR, Fouts DE, Archer GL, Mongodin EF, Deboy RT, Ravel J, Paulsen IT, Kolonay JF, Brinkac L, Beanan M. et al. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(7):2426–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2426-2438.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinane CM, Ben Zakour NL, Tormo-Mas MA, Weinert LA, Lowder BV, Cartwright RA, Smyth DS, Smyth CJ, Lindsay JA, Gould KA. et al. Evolutionary genomics of Staphylococcus aureus reveals insights into the origin and molecular basis of ruminant host adaptation. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:454–466. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowder BV, Guinane CM, Ben Zakour NL, Weinert LA, Conway-Morris A, Cartwright RA, Simpson AJ, Rambaut A, Nubel U, Fitzgerald JR. Recent human-to-poultry host jump, adaptation, and pandemic spread of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(46):19545–19550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909285106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden MT, Feil EJ, Lindsay JA, Peacock SJ, Day NP, Enright MC, Foster TJ, Moore CE, Hurst L, Atkin R. et al. Complete genomes of two clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains: evidence for the rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(26):9786–9791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402521101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neoh HM, Cui L, Yuzawa H, Takeuchi F, Matsuo M, Hiramatsu K. Mutated response regulator graR is responsible for phenotypic conversion of Staphylococcus aureus from heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate resistance to vancomycin-intermediate resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(1):45–53. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00534-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y. et al. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2001;357(9264):1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Takeuchi F, Kuroda M, Yuzawa H, Aoki K, Oguchi A, Nagai Y, Iwama N, Asano K, Naimi T. et al. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet. 2002;359(9320):1819–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08713-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Bae T, Schneewind O, Takeuchi F, Hiramatsu K. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes: polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(1):300–310. doi: 10.1128/JB.01000-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herron-Olson L, Fitzgerald JR, Musser JM, Kapur V. Molecular correlates of host specialization in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2007;2(10):e1120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG, Lin F, Lin J, Carleton HA, Mongodin EF. et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highlander SK, Hulten KG, Qin X, Jiang H, Yerrapragada S, Mason EO Jr, Shang Y, Williams TM, Fortunov RM, Liu Y. et al. Subtle genetic changes enhance virulence of methicillin resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Ames B, Gorovits E, Prater BD, Syribeys P, Vernachio JH, Patti JM. SdrX, a serine-aspartate repeat protein expressed by Staphylococcus capitis with collagen VI binding activity. Infect Immun. 2004;72(11):6237–6244. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6237-6244.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein R, Nerz C, Biswas L, Resch A, Raddatz G, Schuster SC, Gotz F. Genome analysis of the meat starter culture bacterium Staphylococcus carnosus TM300. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(3):811–822. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01982-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Ren SX, Li HL, Wang YX, Fu G, Yang J, Qin ZQ, Miao YG, Wang WY, Chen RS. et al. Genome-based analysis of virulence genes in a non-biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis strain (ATCC 12228) Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(6):1577–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi F, Watanabe S, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Ito T, Morimoto Y, Kuroda M, Cui L, Takahashi M, Ankai A. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus haemolyticus uncovers the extreme plasticity of its genome and the evolution of human-colonizing staphylococcal species. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(21):7292–7308. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7292-7308.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse H, Tsoi HW, Leung SP, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus lugdunensis strain HKU09-01. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(5):1471–1472. doi: 10.1128/JB.01627-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse H, Tsoi HW, Leung SP, Urquhart IJ, Lau SK, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Complete Genome Sequence of the Veterinary Pathogen Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Strain HKU10-03, Isolated in a Case of Canine Pyoderma. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(7):1783–1784. doi: 10.1128/JB.00023-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda M, Yamashita A, Hirakawa H, Kumano M, Morikawa K, Higashide M, Maruyama A, Inose Y, Matoba K, Toh H. et al. Whole genome sequence of Staphylococcus saprophyticus reveals the pathogenesis of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(37):13272–13277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich JE, Block D, Boulez K, Brenner SE, Chervitz SA, Dagdigian C, Fuellen G, Gilbert JG, Korf I, Lapp H. et al. The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. Genome Res. 2002;12(10):1611–1618. doi: 10.1101/gr.361602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa K, Mori K, Ikeda K, Matsuzaki T, Kobayashi Y, Tomita M. G-language Genome Analysis Environment: a workbench for nucleotide sequence data mining. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(2):305–306. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa K, Suzuki H, Tomita M. Computational Genome Analysis Using The G-language System. Genes, Genomes and Genomics. 2008;2(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa K, Tomita M. G-language System as a platform for large-scale analysis of high-throughput omics data. J Pesticide Sci. 2006;31(3):282–288. doi: 10.1584/jpestics.31.282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R_Development_Core_Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2010.

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen S. PhD thesis. University of Utrecht; 2000. Graph Clustering by Flow Simulation. [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, Kiryutin B, Galperin MY, Fedorova ND, Koonin EV. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsen T, Beck E, Ganapathy A, Montgomery R, Zafar N, Yang Q, Madupu R, Goetz P, Galinsky K, White O, The comprehensive microbial resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010. pp. D340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Begley T, Butler RM, Choudhuri JV, Chuang HY, Cohoon M, de Crecy-Lagard V, Diaz N, Disz T, Edwards R. et al. The subsystems approach to genome annotation and its use in the project to annotate 1000 genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(17):5691–5702. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yang J, Yu J, Yao Z, Sun L, Shen Y, Jin Q. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005. pp. D325–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhou CE, Smith J, Lam M, Zemla A, Dyer MD, Slezak T. MvirDB--a microbial database of protein toxins, virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes for bio-defence applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007. pp. D391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010. pp. D211–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25(1):25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi A, Thomson NR, Ogura Y, Saunders D, Ooka T, Henderson IR, Harris D, Asadulghani M, Kurokawa K, Dean P. et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O127:H6 strain E2348/69. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(1):347–354. doi: 10.1128/JB.01238-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshan U, Livesay DR. Probalign: multiple sequence alignment using partition function posterior probabilities. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(22):2715–2721. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol. 2010;59(3):307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52(5):696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP - Phylogeny Inference Package (Version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran J, Holder MT. DendroPy: a Python library for phylogenetic computing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(12):1569–1571. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(2):289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand F, Meyer A, Eyre-Walker A. Evidence of selection upon genomic GC-content in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foerstner KU, von Mering C, Hooper SD, Bork P. Environments shape the nucleotide composition of genomes. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(12):1208–1213. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EP, Danchin A. Base composition bias might result from competition for metabolic resources. Trends Genet. 2002;18(6):291–294. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya H, Romero H, Zavala A, Alvarez B, Musto H. Aerobiosis increases the genomic guanine plus cytosine content (GC%) in prokaryotes. J Mol Evol. 2002;55(3):260–264. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan CE, Gatherer D, McEwan NR. Nitrogen-fixing aerobic bacteria have higher genomic GC content than non-fixing species within the same genus. Hereditas. 1998;128(2):173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.1998.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PM, Bailes E, Grocock RJ, Peden JF, Sockett RE. Variation in the strength of selected codon usage bias among bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(4):1141–1153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos WE, Bannerman TL. Update on clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7(1):117–140. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriese LA, Vancanneyt M, Baele M, Vaneechoutte M, De Graef E, Snauwaert C, Cleenwerck I, Dawyndt P, Swings J, Decostere A. et al. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species from animals. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55(Pt 4):1569–1573. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoovels L, Vankeerberghen A, Boel A, Van Vaerenbergh K, De Beenhouwer H. First case of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius infection in a human. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(12):4609–4612. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01308-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Who's your neighbor? New computational approaches for functional genomics. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(6):609–613. doi: 10.1038/76443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekinne J-A, Ostyn A, Guillier F, Herbin S, Prufer A-L, Dragacci S. How Should Staphylococcal Food Poisoning Outbreaks Be Characterized? Toxins. 2010;2:2106–2116. doi: 10.3390/toxins2082106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Ma XX, Takeuchi F, Okuma K, Yuzawa H, Hiramatsu K. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(7):2637–2651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2637-2651.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Archer GL. Roles of CcrA and CcrB in excision and integration of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec, a Staphylococcus aureus genomic island. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(12):3204–3212. doi: 10.1128/JB.01520-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen AM, Ericson Sollid JU. SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;46(1):8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuda CC, Fisher JF, Mobashery S. Beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: the adaptive resistance of a plastic genome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62(22):2617–2633. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernodle DS. In: Gram-Positive Pathogens. Fischetti VA NR, Ferretti JJ, Portnoy DA, Rood J, editor. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006. Mechanisms of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics; pp. 769–781. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl K, Bischoff M, Berger-Bachi B. CcpA mediates the catabolite repression of tst in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2008;76(11):5093–5099. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00724-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goerke C, Pantucek R, Holtfreter S, Schulte B, Zink M, Grumann D, Broker BM, Doskar J, Wolz C. Diversity of prophages in dominant Staphylococcus aureus clonal lineages. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(11):3462–3468. doi: 10.1128/JB.01804-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CW, Kyme P, Low J, Rocha MA, Alsabeh R, Miller LG, Otto M, Arditi M, Diep BA, Nizet V. et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin contributes to inflammation and muscle tissue injury. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura CL, Malachowa N, Hammer CH, Nardone GA, Robinson MA, Kobayashi SD, DeLeo FR. Identification of a novel Staphylococcus aureus two-component leukotoxin using cell surface proteomics. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerketorp J, Jacobsson K, Frykberg L. The von Willebrand factor-binding protein (vWbp) of Staphylococcus aureus is a coagulase. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;234(2):309–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DQ, Lundberg F, Ljungh A. Binding of von Willebrand factor by coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49(3):217–225. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-3-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YJ, Saier MH Jr. Overexpression of the Escherichia coli sugE gene confers resistance to a narrow range of quaternary ammonium compounds. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(9):2543–2545. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.9.2543-2545.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burts ML, DeDent AC, Missiakas DM. EsaC substrate for the ESAT-6 secretion pathway and its role in persistent infections of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2008;69(3):736–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Genomic information of the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402. Supplementary Table S2. Gene content table for the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402. The first 13 columns contain the protein family identification number, partial sequence (0, no; 1, one side; 2, both sides), amino acid length (Laa), locus_tag or protein_id (tag), functional annotations from different databases: COG, GenBank, JCVI, KEGG, VFDB, MvirDB, Pfam, and GO. The remaining columns show binary data (1 or 0) for presence or absence of each protein family for each of the 29 strains. Supplementary Table S3. Protein families present in Staphylococcus aureus and absent in other Staphylococcus species, and vice versa. The first 13 columns are explained in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Table S4. Protein families present in Staphylococcus simiae and absent in other Staphylococcus species, and vice versa. The first 13 columns are explained in Supplementary Table S2. Supplementary Table S5. Database categories that are over- or underrepresented in Staphylococcus aureus relative to Staphylococcus simiae. a = the number of the S. aureus strains' protein families in this category, b = the number of the S. aureus strains' protein families not in this category, c = the number of the S. simiae strain's protein families in this category, d = the number of the S. simiae strain's protein families not in this category, odds ratio = ad/bc, p-value obtained by Fisher's exact test, and q-value (false discovery rate adjusted p-value).

Supplementary Figure S1. A majority rule consensus of the maximum likelihood trees obtained from nucleotide sequences of the orthologous core genes for the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402 (outgroup). The percentages of genes that support the branches of the tree are indicated.

Supplementary Figure S2. A heatmap showing % identity values of TBLASTN (E-value cutoff of 1e-5) best hits in the 28 Staphylococcus strains and Macrococcus caseolyticus JCSCS5402, against Staphylococcus virulence genes deposited in Virulence Factors Database (VFDB).