Abstract

Background

It is not known whether exposure to smoking depicted in movies carries greater influence during early or late adolescence. We aimed to quantify the independent relative contribution to established smoking of exposure to smoking depicted in movies during both early and late adolescence.

Methods

We prospectively assessed 2049 nonsmoking students recruited from 14 randomly selected public schools in New Hampshire and Vermont. At baseline enrollment, students aged 10–14 years completed a written survey to determine personal, family, and sociodemographic characteristics and exposure to depictions of smoking in the movies (early exposure). Seven years later, we conducted follow-up telephone interviews to ascertain follow-up exposure to movie smoking (late exposure) and smoking behavior. We used multiple regression models to assess associations between early and late exposure and development of established smoking.

Results

One-sixth (17.3%) of the sample progressed to established smoking. In analyses that controlled for covariates and included early and late exposure in the same model, we found that students in the highest quartile for early exposure had 73% greater risk of established smoking than those in the lowest quartile for early exposure (27.8% vs 8.6%; relative risk for Q4 vs Q1 = 1.73, 95% confidence interval = 1.14 to 2.62). However, late exposure to depictions of smoking in movies was not statistically significantly associated with established smoking (22.1% vs 14.0%; relative risk for Q4 vs Q1 = 1.13, 95% confidence interval = 0.89 to 1.44). Whereas 31.6% of established smoking was attributable to early exposure, only an additional 5.3% was attributable to late exposure.

Conclusions

Early exposure to smoking depicted in movies is associated with established smoking among adolescents. Educational and policy-related interventions should focus on minimizing early exposure to smoking depicted in movies.

CONTEXTS AND CAVEATS

Prior knowledge

There were few studies of the association between exposure to smoking depicted in movies and acquisition of established smoking behavior, and none addressed the age at which smoking in movies might be most influential.

Study design

Data were collected from 2049 students in New England who were not established smokers at baseline and who completed written surveys in 1999 (at ages 9–14 years) and follow-up telephone interviews in 2006–2007 (at ages 16–22 years) regarding background, movies watched, and tobacco use. For both of these time points, which reflected early and late exposure, movie data were evaluated for smoking episodes, and subjects were divided into quartiles based on the number of smoking episodes watched. Poisson regression was used to estimate relative risks of becoming an established smoker between individuals in the lowest and highest quartiles of movie smoking exposure.

Contributions

Acquisition of established smoking behavior increased with the number of smoking episodes watched. Students who were in the highest quartile of exposure to smoking in movies at ages 9–14 years were at 73% higher risk of becoming established smokers than peers who watched fewer smoking episodes. However, students who were in the highest quartile of exposure at ages 16–22 years were not at statistically significantly greater risk than peers who saw fewer smoking episodes.

Implication

Younger children appear to be more influenced by exposure to smoking in movies than late adolescents.

Limitations

The study results may have been influenced by which students participated in follow-up, and it remains to be seen whether these results are generalizable to different demographics. There may also be limitations to the methods used in calculating attributable risk.

From the Editors

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States (1), and approximately 90% of individuals who die from smoking begin to smoke during adolescence (2). Although smoking is associated with multiple sociodemographic, personal, and environmental factors (2), evidence indicates that exposure to smoking depicted in movies is a strong risk factor for smoking outcomes among adolescents (3–5).

A link between exposure to smoking depicted in movies and development of an actual smoking habit is supported by theoretical arguments (6), laboratory experiments (7,8), and population-based studies that have assessed early indicators of smoking, including smoking susceptibility and initiation (3–5,9–16). However, because the majority of adolescent experimenters do not progress to subsequent stages of smoking (17), it is important to focus on the outcome of established smoking behavior, which is strongly related to morbidity and mortality (18,19).

A few studies have assessed the association between smoking depicted in movies and established smoking behavior. One focused primarily on the influence of participation in sports on this association (20). Another study, because of relatively brief follow-up, was able to demonstrate only a difference between those with extremely high and extremely low exposure to smoking depicted in movies (those in the 95th vs 5th percentiles) (21). Although a third study demonstrated an association between early smoking exposure and long-term established smoking behavior (22), it involved only one baseline measurement of exposure to smoking depicted in movies during a 7-year period. As a result, we could learn very little from that study about the developmental time period at which youth are most susceptible to this exposure. Because early adolescence coincides with pivotal developmental stages related to identity formation, exposure to smoking depicted in movies during early adolescence may more strongly influence attitudes and beliefs related to substance use than exposure during late adolescence (23,24). Conversely, because late adolescence is closer to the time when smoking patterns are usually established, exposure to smoking depicted in movies during this period may be more influential (17,25).

By determining the stage at which children are maximally vulnerable to visual stimuli that persuade them to smoke, we might better plan the timing, content, and context of future interventions aimed at reducing a principal risk factor for the leading cause of preventable death. We therefore designed a longitudinal study to assess the relative contribution of early and late exposure to smoking depicted in movies on establishment of smoking habits among adolescents.

Subjects and Methods

Study Setting and Participants

Study participants were students who were enrolled in the fifth through eighth grades at 14 randomly selected public middle schools in Vermont and New Hampshire. The study methodology has been reported in detail (3,4) and is briefly summarized here.

In 1999, we collected baseline data from 5473 students with a self-administered in-school written survey. This survey gathered socioeconomic and personal data, information about the students’ previous exposure to smoking depicted in movies, and information about their smoking behavior (3). Students were eligible for analysis if they listed contact information, provided data about exposure and smoking behavior, agreed to participate in the longitudinal study, and had parental consent to participate. Of the 5473 students, 3122 (57.0%) met these eligibility requirements and were enrolled in the longitudinal study. Compared with students who did not enroll in the longitudinal study, those who did enroll were more likely to be female (51.8% vs 48.7%; P = .02), to be white (93.6% vs 89.6%; P < .001), or to have parents who both graduated from high school (82.8% vs 69.0%; P < .001).

In 2006–2007, we used a telephone survey to gather follow-up data from the longitudinal study participants about their exposure to smoking depicted in movies and their smoking behavior. For this survey, trained interviewers used a computer-assisted telephone interview system (4).

The protocol for the study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College.

Measures

Established Smoking.

To assess lifetime smoking experience at baseline and follow-up, we asked the participants “How many cigarettes have you smoked in your life?” and offered five answer options: none, just a few puffs, 1–19 cigarettes, 20–100 cigarettes, or more than 100 cigarettes. Consistent with prior work (22), we classified those who reported smoking more than 100 cigarettes as established smokers.

Exposure to Smoking Depicted in Movies.

As previously described (3,4), we used the Beach method (26) to measure the participants’ exposure to smoking depicted in movies. To assess early exposure, the baseline questionnaire asked participants whether they had seen 50 specific movies randomly selected from a larger list of 601 popular movies that had been released between 1988 and 1999. Each of the 601 movies had been measured previously by trained coders for smoking content (27). We stratified the movie selection so that each student's list of 50 movies had the same distribution of ratings as the larger sample of top movies, with 45% rated R, 31% rated PG-13, 20% rated PG, and 4% rated G. For each participant, we calculated exposure by summing the number of smoking episodes from each movie he or she had seen, expressing this as a proportion of the total number of smoking episodes contained in the 50 movies included in the survey, and multiplying this proportion by the total number of episodes in the full sample of movies (601 movies for baseline). Using a computer-based algorithm (Stata Corp, College Station, TX), we then classified each participant's early exposure in quartiles based on the early exposure distribution for study participants.

To assess late exposure, the follow-up telephone interview queried students about 50 movies randomly selected from a sample of 600 popular movies released between 2000 and 2005. We again stratified the movie selection so that each list of 50 had the same distribution of ratings as the larger sample, of which 30% were rated R, 48% were rated PG-13, 17% were rated PG, and 4% were rated G. The sample of movies for the follow-up survey had proportionately fewer R-rated movies because there were fewer R-rated movies in the top 100 box office hits for those years. We then followed the other procedures outlined above.

Covariates.

The baseline survey gathered information about three types of information that could confound the association between exposure and established smoking behavior: sociodemographic factors, personal factors, and family and social influences. Sociodemographic covariates included sex, race/ethnicity, grade in school, age, and parental education as a proxy for socioeconomic status. Personal factors included self-reported school performance (one item), sensation seeking (six items), rebelliousness (seven items), and self-esteem (eight items). Family and social influences included parental disapproval of smoking, two components of authoritative parenting [supervision and responsiveness; ref (28)] and parental, sibling, and peer smoking. Details about these individual items and the reliability of scales used to measure adolescent personality and parenting characteristics have been reported previously (3).

For some items in the personal, family, and social influence categories (eg, questions about parental, sibling, and peer smoking), we asked participants to respond yes or no. For most other items, we asked participants to use a 4-point Likert-type scale to indicate how well certain statements described them or their primary caregiver, with 1 indicating not at all and 4 indicating very well. We calculated summary scores for these items and then classified participants in terms of tertiles based on the distribution of scores.

Statistical Analyses

We used χ2 tests and bivariable Poisson regression to determine associations and estimate relative risks directly between covariates and our primary outcome, which was established smoking at follow-up. We then built multivariable Poisson regression models that included our two primary predictors (quartiles of early exposure measured at baseline and quartiles of late exposure measured at follow-up), along with potential confounders measured at baseline. We only included in these models potential confounders that demonstrated a bivariable association of P values less than .20 with established smoking. P values were derived from two-sided χ2 tests. These multivariable analyses also controlled for clustering of participants within schools by robust sandwich estimator of variance. We reported the results as relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

We estimated covariate-adjusted attributable risk by calculating the reduced probability of established smoking realized by decreasing each participant's exposure from his or her reported level to the first quartile (29). Multivariable model covariates, all of which were categorical, included sex, grade in school, number of parents who graduated from high school, school performance, sensation seeking, rebelliousness, self-esteem, parental disapproval of smoking, parental supervision, parental responsiveness, and parental, sibling, and peer smoking.

In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses to verify the robustness of our results. First, we conducted regression analyses using stepwise forward regression and stepwise backward regression with P greater than .20 as the criterion for entry and exit from the analyses. Next, we used exposure as a continuous rather than a categorical variable.

Results

Study Sample

Of 3122 participants in the longitudinal study, 2074 (66.4%) completed the follow-up survey. The mean time between baseline and follow-up was 6.7 years (SD = 0.2 years).

Of the 1048 students who did not complete the follow-up survey, 469 could not be located or reached and 579 declined to participate. Compared with students who completed the survey, those who did not were less likely to be female (53.2% vs 48.8%; P = .002), to be white (94.3% vs 90.4%; P < .001), or to have parents who both graduated from high school (84.9% vs 72.3%; P < .001).

Of the 2074 participants who completed the follow-up survey, 25 (1.2%) were classified as established smokers at baseline and were therefore excluded from the statistical analyses. Of the final sample of 2049 participants, 1886 (92.0%) were non-Hispanic white and 1092 (53.3%) were female students. At baseline, the participants’ mean age was 12.1 years (SD = 1.1 years). At follow-up, ages ranged from 16 to 22 years, with a mean of 18.7 years (SD = 1.1 years); 21.2% were in high school, 58.6% were in college, 1.6% were in technical school, and 18.3% were not enrolled in school.

Smoking Experience

At baseline, 250 (12.2%) of the 2049 study participants reported that they had tried smoking. Of these 250 individuals, 176 (70.4%) had smoked less than one cigarette, 56 (22.4%) had smoked 1–19 cigarettes, and 18 (7.2%) had smoked 20–100 cigarettes.

At follow-up, 1057 (51.6%) of the 2049 study participants reported that they had tried smoking. Of those who had tried smoking, 241 (22.8%) smoked less than 1 cigarette, 314 (29.7%) smoked 1–19 cigarettes, 148 (14.0%) smoked 20–100 cigarettes, and 354 (33.5%) smoked more than 100 cigarettes. The 354 participants who smoked more than 100 cigarettes were classified as established smokers and represented 17.3% of the follow-up survey group. Of these 354 participants, the majority (319; 90.1%) were classified as current smokers, having smoked within 30 days before the follow-up survey.

Exposure to Smoking Depicted in Movies

At baseline, participants were exposed to a mean of 1190 episodes of smoking in movies (SD = 900 episodes). For early exposure, quartile (Q) breakdowns were 0–525 episodes in Q1, 526–955 in Q2, 956–1664 in Q3, and 1665–5308 in Q4. At follow-up, participants were exposed to a mean of 1333 episodes (SD = 669 episodes), with quartile breakdowns of 0–837 episodes in Q1, 838–1280 in Q2, 1281–1764 in Q3, and 1765–3495 in Q4. Quartiles of early and late exposure to smoking in movies were correlated (Pearson r = 0.27), but not so much as to raise concern for multicollinearity in the analysis.

Bivariable Analyses

Nearly all baseline characteristics had statistically significant bivariable associations with established smoking at follow-up (Table 1). Factors associated with a higher odds of being an established smoker were male sex, older age, being a sensation-seeker, being rebellious, and having parents, siblings, or peers who smoke. Factors associated with lower odds of being an established smoker were having above-average school performance, high self-esteem, and responsive parents.

Table 1.

Results of bivariable and multivariable analyses of associations between independent variables, covariates, and established smoking at follow-up among 2049 adolescents*

| Variable | No. of participants | Percentage of participants who were established smokers at follow-up | Unadjusted relative risk (95% CI) for established smoking | Adjusted† relative risk (95% CI) for established smoking |

| Exposure to smoking depicted in movies‡ | ||||

| Early exposure | ||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 514 | 8.6 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent)§ |

| Quartile 2 | 511 | 13.1 | 1.53 (1.05 to 2.24) | 1.26 (0.87 to 1.84) |

| Quartile 3 | 513 | 19.7 | 2.30 (1.61 to 3.28) | 1.57 (1.08 to 2.29) |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 511 | 27.8 | 3.25 (2.31 to 4.55) | 1.73 (1.14 to 2.62) |

| Late exposure | ||||

| Quartile 1 (lowest) | 513 | 14.0 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent)‖ |

| Quartile 2 | 512 | 15.2 | 1.09 (0.79 to 1.50) | 1.08 (0.83 to 1.41) |

| Quartile 3 | 512 | 17.8 | 1.27 (0.93 to 1.73) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.29) |

| Quartile 4 (highest) | 512 | 22.1 | 1.57 (1.17 to 2.11) | 1.13 (0.89 to 1.44) |

| Sociodemographic factors¶ | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1092 | 13.7 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Male | 957 | 21.3 | 1.55 (1.26 to 1.92) | 1.34 (1.15 to 1.56) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1886 | 17.5 | 1 (referent) | NA |

| Nonwhite | 113 | 15.0 | 0.86 (0.53 to 1.40) | |

| Grade in school | ||||

| Fifth | 205 | 8.3 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Sixth | 535 | 13.8 | 1.67 (0.98 to 2.83) | 1.63 (0.81 to 3.30) |

| Seventh | 654 | 18.7 | 2.25 (1.35 to 3.74) | 1.94 (1.03 to 3.63) |

| Eighth | 655 | 21.5 | 2.60 (1.57 to 4.30) | 1.91 (0.95 to 3.85) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 9–10 | 188 | 6.9 | 1 (referent) | NA |

| 11 | 450 | 12.0 | 1.74 (0.95 to 3.18) | |

| 12 | 632 | 18.5 | 2.68 (1.51 to 4.75) | |

| 13 | 633 | 22.0 | 3.18 (1.80 to 5.61) | |

| 14 | 146 | 21.2 | 3.10 (1.61 to 5.87) | |

| No. of parents who graduated from high school | ||||

| 0 | 54 | 24.1 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| 1 | 248 | 28.6 | 1.19 (0.66 to 2.15) | 1.59 (0.68 to 3.73) |

| 2 | 1729 | 14.9 | 0.62 (0.35 to 1.08) | 1.10 (0.57 to 2.16) |

| Personal factors¶ | ||||

| School performance | ||||

| Average | 397 | 34.5 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Good | 761 | 16.4 | 0.48 (0.37 to 0.61) | 0.74 (0.60 to 0.90) |

| Excellent | 890 | 10.3 | 0.30 (0.23 to 0.39) | 0.63 (0.46 to 0.86) |

| Sensation seeking | ||||

| Tertile 1 (lowest) | 904 | 9.6 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Tertile 2 | 608 | 17.1 | 1.78 (1.34 to 2.36) | 1.23 (0.96 to 1.59) |

| Tertile 3 (highest) | 532 | 29.9 | 3.11 (2.39 to 4.03) | 1.40 (0.98 to 2.00) |

| Rebelliousness | ||||

| Tertile 1 (lowest) | 1009 | 10.0 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Tertile 2 | 506 | 16.4 | 1.64 (1.23 to 2.19) | 1.10 (0.76 to 1.58) |

| Tertile 3 (highest) | 529 | 31.8 | 3.17 (2.48 to 4.06) | 1.37 (1.00 to 1.88) |

| Self-esteem | ||||

| Tertile 1 (lowest) | 704 | 23.4 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Tertile 2 | 828 | 14.5 | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.78) | 0.91 (0.69 to 1.21) |

| Tertile 3 (highest) | 515 | 13.4 | 0.57 (0.43 to 0.76) | 0.97 (0.68 to 1.38) |

| Family and social influences¶ | ||||

| Parents disapprove of smoking | ||||

| No | 375 | 23.2 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Yes | 1670 | 15.9 | 0.68 (0.54 to 0.87) | 1.00 (0.78 to 1.28) |

| Parental supervision | ||||

| Tertile 1 (lowest) | 752 | 19.2 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Tertile 2 | 842 | 15.3 | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.01) | 0.95 (0.81 to 1.11) |

| Tertile 3 (highest) | 448 | 17.4 | 0.91 (0.69 to 1.20) | 1.24 (1.00 to 1.53) |

| Parental responsiveness | ||||

| Tertile 1 (lowest) | 877 | 21.0 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Tertile 2 | 520 | 14.0 | 0.67 (0.51 to 0.88) | 0.93 (0.75 to 1.15) |

| Tertile 3 (highest) | 647 | 14.5 | 0.69 (0.54 to 0.89) | 1.06 (0.80 to 1.41) |

| Parental smoking | ||||

| No | 1467 | 13.4 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Yes | 581 | 27.0 | 2.02 (1.64 to 2.49) | 1.36 (1.14 to 1.63) |

| Sibling smoking | ||||

| No | 1815 | 14.8 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Yes | 232 | 36.6 | 2.48 (1.94 to 3.17) | 1.29 (1.01 to 1.65) |

| Peer smoking | ||||

| No | 1448 | 11.0 | 1 (referent) | 1 (referent) |

| Yes | 595 | 32.3 | 2.94 (2.38 to 3.63) | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.11) |

CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable.

The adjusted model accounted for clustering of individuals within schools and controlled for the variables listed. Race was not included in the multivariable model because it was not statistically significant in two-sided χ2 models (P < .20). Age was not included in the multivariable model because of collinearity with grade level.

Early exposure was assessed at baseline, and late exposure was assessed at follow-up. For early exposure, the quartile (Q) breakdowns were 0–525 episodes of exposure in Q1, 526–955 in Q2, 956–1664 in Q3, and 1665–5308 in Q4. For late exposure, the breakdowns were 0–837 episodes in Q1, 838–1280 in Q2, 281–1764 in Q3, and 1765–3495 in Q4.

Ptrend = .01 from multiple regression models in which the independent variables (early exposure and late exposure) were replaced with continuous instead of categorical variables.

Ptrend = .32 from multiple regression models as above.

Sociodemographic factors, personal factors, and family and social influences were assessed at baseline.

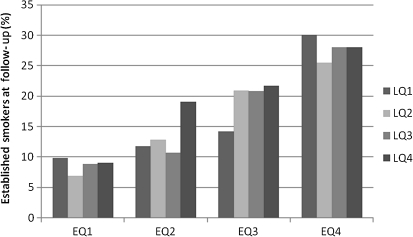

The percentage of participants who progressed to established smoking varied by quartile of early and late exposure period (Figure 1). For example, of those who were in the lowest quartile of exposure at both baseline and follow-up (EQ1 and LQ1), 9.8% progressed to established smoking. Of those who were in the highest quartile of exposure at baseline and the lowest quartile of exposure (EQ4 and LQ1) at follow-up, 30.0% progressed to established smoking. The percentage of students who were established smokers increased from 8.6% to 13.1% to 19.7% to 27.8% for the first (lowest), second, third, and fourth (highest) quartiles of early exposure, respectively. A less pronounced progression was observed for late exposure; the percentage of established smokers was 14.0%, 15.2%, 17.8%, and 22.1%, respectively, for the lowest to highest quartile of late exposure.

Figure 1.

Established smoking among adolescents and its relationship to early vs late exposure to smoking depicted in movies. Early exposure was assessed at baseline (youths aged 10–14 years), and late exposure was assessed at follow-up (youths aged 17–21 years). For early exposure, the quartile (EQ) breakdowns were 0–525 episodes of exposure in EQ1, 526–955 in EQ2, 956-1664 in EQ3, and 1665–5308 in EQ4. For late exposure, the quartile (LQ) breakdowns were 0–837 episodes in LQ1, 838–1280 in LQ2, 281–1764 in LQ3, and 1765–3495 in LQ4.

Multivariable Analyses

In analyses that controlled for covariates and included early and late exposure in the same statistical model (last column of Table 1), students in the highest quartile of early exposure had a 73% greater risk of smoking than those in the lowest quartile for early exposure (RR for Q4 vs Q1 = 1.73; 95% CI = 1.14 to 2.62). However, risk did not differ for those in the highest and lowest quartiles of late exposure (RR for Q4 vs Q1 = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.89 to 1.44).

According to attributable risk models, early exposure was responsible for 31.6% (95% CI = 10.1 to 53.2) of established smoking in these adolescents. This suggests, for example, that if baseline exposure for all participants were reduced to the lowest quartile, the percent of established smokers at follow-up would decrease from 17.3% to 11.9%. However, only an additional 5.3% (95% CI = −7.0 to 17.5) of established smoking was attributable to late exposure.

Sensitivity Analyses

Results of multivariable analyses were similar to those presented above when we used stepwise backward regression and stepwise forward regression. They were also the same regardless of whether we treated exposure as a linear variable or categorical variable.

Discussion

These results indicate that early exposure to smoking depicted in movies is associated with established smoking in adolescents, whereas late exposure is not. Attributable risk calculations suggest that reducing early exposure to the levels of the lowest exposure group could substantially reduce the number of adolescents who become established smokers, which would likely be associated with reductions in morbidity and mortality.

A previous study of smoking initiation similarly showed that movie-related exposures occurring in childhood were as influential as those occurring closer to smoking initiation (6). These findings are also compatible with a report finding an association between restriction of viewing of R-rated movies and lower smoking initiation (30). Finally, our study results are consistent with social cognitive theory, which suggests that exposure to glamorized portrayals of smoking in movies may promote identification with smokers and positive expectations that may influence smoking behavior via attitudes and cognitions (10). However, our analysis goes beyond many other studies in its use of established smoking as a long-term primary outcome. Additionally, this study parses out the relative influence of movie smoking during different developmental stages of youth. Thus, our study supports and extends earlier findings, lending further credence to childhood as a critical period for reducing risk of smoking associated with media exposures.

Being in the highest quartile of early exposure was associated with a 73% increase in the relative risk of becoming an established smoker. This suggests that early exposure to smoking depicted in movies is a stronger risk factor than many other factors previously assumed to be highly potent, including parent, sibling, and peer smoking, which had relative risks of 1.36, 1.29, and 1.64, respectively.

Most social influences on adolescent smoking generally are better predictors when measured more proximally to the time of smoking initiation (31,32). Our findings, however, suggest that efforts to reduce movie smoking exposure should target young age groups. Doing so may facilitate intervention, as early adolescent exposures are easier to influence compared with late adolescent exposures. One way of reducing early adolescent exposure to depictions of smoking in movies would be to eliminate smoking from all youth-rated movies. Although smoking in youth-rated movies has decreased substantially during the past 5 years, greater than 30% of youth-rated movies (G, PG, and PG-13) still contain scenes involving smoking (33). Interventions may also be needed to increase parental awareness of the importance of minimizing exposure to smoking in movies during childhood and early adolescence. However, because many parents do not believe that smoking in movies poses a risk for smoking behavior (34), even if smoking descriptors were consistently applied, parents may not be motivated to restrict their children's exposure. Rating all movies with smoking “R,” therefore, may represent the most effective means of eliminating exposure through youth-rated movies.

In addition to minimizing exposure to smoking-related media, smoking media literacy—an educational approach involving the analysis and evaluation of media messages containing smoking—may buffer the influence of the media messages on smoking behaviors (35–37). Our findings therefore suggest that this type of prevention may be particularly valuable during early developmental stages, as soon as youth are able to understand the concepts.

The generalizability of our findings may be limited by the demographic characteristics of our sample, which predominantly consisted of white students from northern New England public schools. It is also possible that the influence of movie smoking exposure begins even earlier in childhood, which we were unable to assess. Our study results, however, indicate that preventive efforts should not be delayed past early adolescence.

The characteristics of students who participated in follow-up suggested that they were of lower risk of smoking than those who discontinued participation. Because previous studies suggest that lower-risk youth are more susceptible to movie-related smoking influences (20), this may have resulted in an overestimate of the effect of movie smoking. However, it is also possible that we underestimated the effect of movie smoking because some students were only 16–17 years old at follow-up, which may not be old enough for some youth to have become fully established smokers.

Although we included 14 covariates in our models representing various domains, there is always the possibility of residual confounding. It may therefore be valuable for future studies to consider other possible covariates. Similarly, although we used robust analyses, other approaches to modeling, such as semiparametric models, may be valuable to explore in the future.

Finally, there are limitations in the interpretation of our attributable risk percentage, which was calculated as the difference between the fully adjusted risk of being an established smoker for the reported quartile of movie smoking exposure, and the predicted risk if movie smoking exposure was reduced to the first quartile. In particular, although this is considered an established and valid method of calculating attributable risk, it assumes that no other forces would replace smoking in movies as an influence and its generalizability to different populations needs to be demonstrated.

Despite these limitations, our results demonstrate a strong, independent longitudinal association between early exposure to smoking depicted in movies and established smoking in adolescents, even when simultaneously considering the influence of late adolescent exposure to smoking depicted in movies. These findings suggest that prevention efforts should focus on the reduction of exposure to smoking depicted in movies when children are at a young age.

Footnotes

The funding source had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the article.

The authors would like to thank M. Bridget Ahrens, Loren Bush, and Aaron Jenkyn for data collection; Jennifer Tickle, Elaina Bergamini, Daniel Nassau, and Bindi Rakhra for coding the movies; and Susan Martin for providing administrative support. These individuals were all compensated for their work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA077026 and R01-CA108918 to MD and K07-CA114315 to BP).

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People, A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, et al. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323(7326):1394–1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362(9380):281–285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sargent J, Beach M, Adachi-Mejia A, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking initiation among U.S. adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wakefield M, Flay B, Nichter M, Giovino G. Role of the media in influencing trajectories of youth smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 1):79–103. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lochbuehler K, Peters M, Scholte RH, Engels RC. Effects of smoking cues in movies on immediate smoking behavior. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(9):913–918. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shmueli D, Prochaska JJ, Glantz SA. Effect of smoking scenes in films on immediate smoking: a randomized controlled study. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Distefan JM, Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. Do favorite movie stars influence adolescent smoking initiation? Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1239–1244. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, Heatherton TF. Favourite movie stars, their tobacco use in contemporary movies, and its association with adolescent smoking. Tob Control. 2001;10(1):16–22. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Titus-Ernstoff L, Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, Beach ML. A longitudinal study of viewing smoking in movies and smoking initiation in children. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):15–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Sargent JD, et al. Relation between parental restrictions on movies and adolescent use of tobacco and alcohol. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargent JD, Dalton MA, Beach ML, et al. Viewing tobacco use in movies: does it shape attitudes that mediate adolescent smoking? Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(3):137–145. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00434-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pechmann C, Shih CF. Smoking scenes in movies and antismoking advertisements before movies: effects on youth. J Marketing. 1999;63(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalton MA, Adachi-Mejia AM, Longacre MR, et al. Parental rules and monitoring of children's movie viewing associated with children's risk for smoking and drinking. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1932–1942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in internationally distributed American movies and youth smoking in Germany: a cross-cultural cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e108–e117. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karp I, O’Loughlin J, Paradis G, Hanley J, Difranza J. Smoking trajectories of adolescent novice smokers in a longitudinal study of tobacco use. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(6):445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu D, Kelly TN, Wu X, et al. Mortality attributable to smoking in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(2):150–159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jha P, Jacob B, Gajalakshmi V, et al. A nationally representative case-control study of smoking and death in India. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1137–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi-Mejia AM, Primack BA, Beach ML, et al. Influence of movie smoking exposure and team sports participation on established smoking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(7):638–643. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Worth KA, et al. Exposure to smoking depictions in movies: its association with established adolescent smoking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(9):849–856. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalton MA, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Early exposure to movie smoking predicts established smoking by older teens and young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e551–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS, et al. Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychol Sci. 2008;19(10):1037–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zapert K, Snow DL, Tebes JK. Patterns of substance use in early through late adolescence. Am J Community Psychol. 2002;30(6):835–852. doi: 10.1023/A:1020257103376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sargent JD, Worth KA, Beach M, Gerard M, Heatherton T. Population based assessment of exposure to risk behaviors in motion pictures. Commun Methods Meas. 2008;2(1–2):1–18. doi: 10.1080/19312450802063404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. The incidence and context of tobacco use in popular movies from 1988 to 1997. Prev Med. 2002;34(5):516–523. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(3):319–337. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benichou J. A review of adjusted estimators of attributable risk. Stat Methods Med Res. 2001;10(3):195–216. doi: 10.1177/096228020101000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Leeuw RN, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Tanski SE. Association of smoking onset with R-rated movie restrictions and adolescent sensation seeking. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e96–e105. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Reducing early smokers’ risk for future smoking and other problem behavior: insights from a five-year longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(4):394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bricker J, Peterson AJ, Andersen M, Rajan K, Leroux B, Sarason I. Childhood friends who smoke: do they influence adolescents to make smoking transitions? Addict Behav. 2006;31(5):889–900. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glantz SA, Mitchell S, Titus K, Polansky JR, Kaufmann RB, Bauer UE. Smoking in top-grossing movies, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(27):909–913. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Longacre MR, Adachi-Mejia AM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson JJ, Beach ML, Dalton MA. Parental attitudes about cigarette smoking and alcohol use in the Motion Picture Association of America rating system. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(3):218–224. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, Austin EW. Media literacy education for elementary school substance use prevention: study of media detective. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):525–531. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Primack BA, Fine D, Yang CK, Wickett D, Zickmund S. Adolescents’ impressions of antismoking media literacy education: qualitative results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(4):608–621. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Primack BA, Gold MA, Land SR, Fine MJ. Association of cigarette smoking and media literacy about smoking among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(4):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]