Abstract

Cyclic soft palate elevation is temporally associated with masticatory jaw movement. However, the soft palate is normally lowered during nasal breathing to maintain retropalatal airway patency. We tested the hypothesis that the frequency and amplitude of soft palate elevation associated with mastication would be reduced during inspiration. Movements of radiopaque soft palate markers were recorded by videofluorography while 11 healthy volunteers ate solid foods. Breathing was monitored with plethysmography. Masticatory sequences were divided into processing and stage II transport cycles (food transport to the oropharynx before swallowing). In food processing, palatal elevation was less frequent and its displacement was smaller during inspiration than expiration. In stage II transport, the soft palate was elevated less frequently during inspiration than expiration. These findings suggest that masticatory soft palate movement is diminished during inspiration. The control of breathing appears to have a significant effect on soft palate elevation in mastication.

Keywords: deglutition/physiology, fluoroscopy, breathing, eating

Introduction

The pathways for air and food cross in the pharynx. While air flows through the pharynx for breathing, the food bolus accumulates in the pharynx during mastication before being swallowed (Palmer et al., 1992). There is significant risk of food inhalation during bolus aggregation in the pharynx. Thus, the fine temporal coordination among breathing, mastication, and swallowing is essential to providing proper food nutrition and to preventing pulmonary aspiration. The soft palate, which forms the roof of the oral cavity and oropharynx, serves functions in feeding and breathing, and could have a role in protecting the airway during oropharyngeal bolus aggregation.

During mastication, cyclic soft palate elevation is temporally associated with jaw movement during the eating of solid food: The soft palate moves upward as the jaw opens and downward as the jaw closes (Matsuo et al., 2005, 2008). Soft palate elevation opens the fauces, providing a route for bolus transport from the oral cavity to the pharynx (stage II transport) before swallowing. Soft palate elevation occurs in about 40% of jaw motion cycles during mastication.

During nasal breathing, palatal muscles lower the soft palate, apposing it to the tongue and closing the fauces. This prevents the airway from collapsing during inspiration (Rodenstein and Stanescu, 1986; Mortimore et al., 1995; Tangel et al., 1995; Launois et al., 1996). During eating, nasal breathing usually occurs while food is processed in the mouth. The behaviors of nasal breathing and eating promote soft palate motion in opposite directions: The soft palate is lowered for nasal breathing, but elevates cyclically during eating (to open the fauces). We examined the effect of respiratory phase (direction of airflow) on soft palate movement during eating to determine how these competing factors are integrated. We hypothesized that soft palate elevation associated with mastication would be reduced during inspiration.

Materials & Methods

To recruit potential volunteers, we posted advertisement fliers in the local community, including stores, community centers, and universities. Notice was posted on the department official Web site. Medical students, faculty in the principle investigator’s department, and hospital employees were excluded from the volunteer pool to avoid the conflict of interest. Each study participant received payment after completing the study. Eventually, 11 healthy asymptomatic volunteers (six males and five females; mean age, 24 yrs; range, 19-37 yrs) participated in this study after giving informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 86-06-25-03).

Data Acquisition

Small metal markers were glued to the left upper molar and canines. To quantify soft palate movement, after topical anesthesia of the nares, a small metal pellet marker glued to the tip of a flexible rubber tube was passed transnasally. Participants did not report discomfort, probably because the tube was small and flexible and we used topical anesthesia. The soft palate marker was positioned on the upper surface of the soft palate approximately midway between the posterior nasal spine and the tip of the uvula (Fig. 1A). Marker position was monitored with fluoroscopy and adjusted whenever necessary to maintain the proper position during recording.

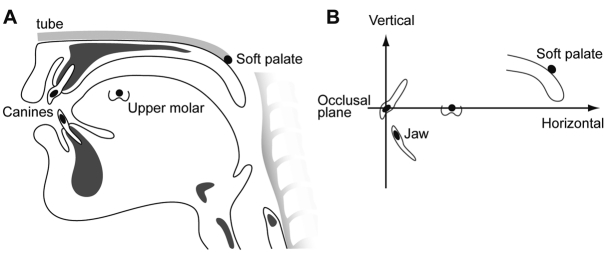

Figure 1.

Locations of the soft palate and jaw markers and those positions in Cartesian coordinates. (A) A small metal pellet (4 mm diameter, 0.2 g) glued to the tip of a thin flexible rubber tube (internal diameter 1.5 mm) was placed on the surface of the center of the soft palate transnasally. The other end of the tube was taped to the face of the participant. Radiopaque lead markers (5 mm diameter) were also cemented to the buccal surfaces of the left upper and lower canines and first molars to measure movement of the jaws. (B) The position of the soft palate and jaw was expressed in Cartesian coordinates (in mm) with the upper canine at the origin. The upper occlusal plane, defined by a line passing through the upper canine and molar markers, was the horizontal axis (X axis). The line perpendicular to the X axis at the upper canine was the vertical axis (Y axis).

Participants were seated upright comfortably in a chair and ate 6 g each of banana, chicken spread, and cookie lightly coated with barium paste, while videofluorography in lateral projection was recorded on a digital video recorder (BR-DV3000U, JVC, Yokohama, Japan) at 30 frames/sec. We recorded two trials with the soft palate marker and one trial without the marker for each food.

Respiration was monitored on a respiratory plethysmograph with bands around the chest and abdomen. The respiratory signals were collected on a digital data recorder at a 1.0-KHz acquisition rate. A square-wave spike signal was created on the digital data recorder simultaneously with a distinctive square flash image on the videofluorographic images synchronizing the respiratory data and videofluorographic images.

Data Reduction

All recordings were reviewed carefully in slow motion. Recordings were excluded from further analysis if the soft palate marker was not positioned on the middle one-third of the soft palate, or if the food was swallowed without being chewed; 54 out of 66 videofluorographic recordings were included in the data processing and analysis.

Positions of the radiopaque markers on the soft palate and upper and lower teeth were measured frame by frame with an image processing program, and then plotted over time relative to the upper occlusal plane (Fig. 1B). Jaw motion was divided into cycles starting at one minimum gape (the end of visible upward movement) and ending at the next. Cycles were each classified as one of the following three cycle types (Matsuo et al., 2005):

(1) Processing cycles. These are defined as chewing cycles without stage II transport.

(2) Stage II transport cycles. These are defined as the cycles in which food was propelled backward by the tongue, food passing below the posterior nasal spine and through the fauces to the oropharynx. Stage II transport cycles were interposed among processing cycles but mostly occurred late in the masticatory sequence (Palmer et al., 1992).

(3) Swallowing cycles. Based on our previous study (Matsuo et al., 2005), soft palate elevation cycles in feeding were classified into the following patterns by slow motion review of the recordings (Fig. 2):

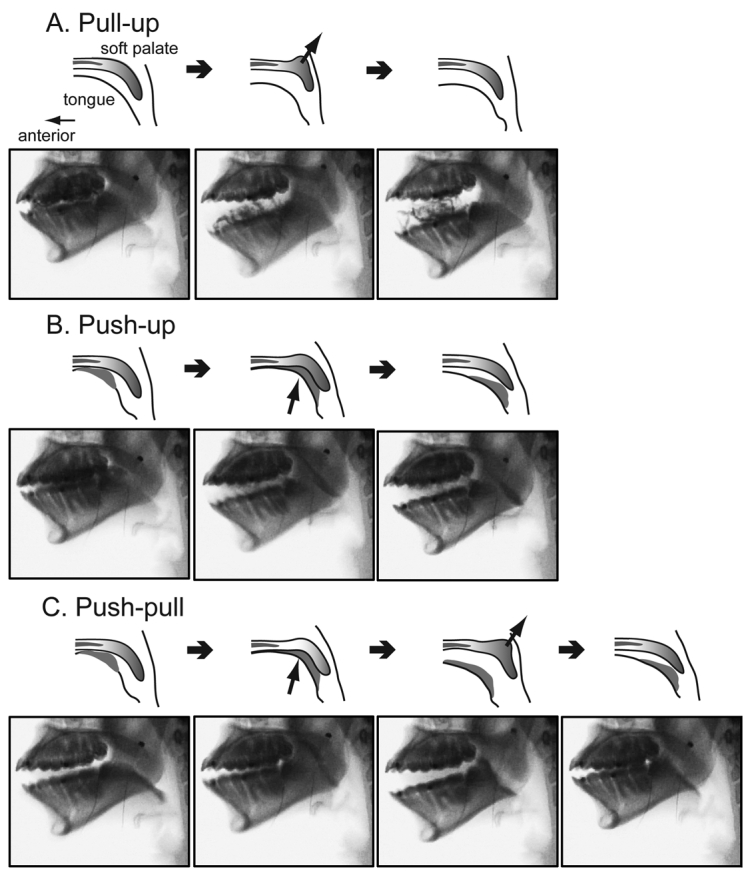

Figure 2.

Drawings and videofluorographic images of the three patterns of soft palate elevation occurring during mastication. (A) Pull-up pattern; the soft palate elevated independently of the tongue. Soft palate was drawn upward by contraction of its levator muscles. (B) Push-up pattern; the soft palate was pushed upward by the tongue. (C) Push-pull pattern; soft palate push-up followed by pull-up. The arrows indicate pulling and pushing of the soft palate movement. In B and C, the gray material between the tongue surface and the soft palate represents a bolus of food that is propelled by the tongue during stage II transport.

(a) Pull-up pattern. These had no tongue-palate contact, and soft palate elevation typically occurred during jaw opening, so we infer that the soft palate was pulled upward and backward by its levator musculature.

(b) Push-up pattern. There was visible tongue-palate contact, and the soft palate was clearly pushed upward by the rising surface of the tongue.

(c) Push-Pull pattern. The soft palate was pushed upward by the tongue (as in push-up) and then subsequently pulled upward and backward, rising above the tongue surface (as in pull-up).

(d) No-up pattern. This refers to jaw motion cycles with no concurrent soft palate elevation.

Respiratory cycles were identified from the plethysmography data with signal analysis software. An inspiratory phase was defined as the time from onset to end of inspiration, and the expiratory phase was defined as the time from end of inspiration to onset of the next inspiration.

Data Analysis

The soft palate marker had no significant effect on respiratory pattern or on the frequency of soft palate movement. For all participants combined, respiratory cycle duration was 3.4 ± 0.8 sec (mean ± SD) with and 3.2 ± 0.8 sec without the soft palate marker (p = 0.11, two-sample t test). Pull-up motion (including pull-up and push-pull) occurred in 51% (399/784) of jaw cycles with and 55% (218/396) without the soft palate marker (p = 0.20, Fisher’s exact test).

The onsets of soft palate elevation and minimum jaw gape were nearly synchronous (overall mean difference 0.01 ± 0.14 sec), and were in the same respiratory phase for 96% of their occurrences. To test the effect of the respiratory phase on soft palate movement, we first identified the respiratory phase at the onset of minimum gape for each jaw cycle, and then noted the type of soft palate elevation pattern occurring concurrently with that jaw cycle.

Frequency of Soft Palate Movement

The frequency of soft palate movement was defined as the percentage of jaw cycles having concurrent soft palate elevation (Matsuo et al., 2005). The frequency of each soft palate elevation pattern was then calculated by respiratory phase and food type. We hypothesized that soft palate elevation was less frequent for jaw cycles occurring during inspiration. Our null hypothesis was that the frequency of jaw cycles during inspiration was the same for cycles with and cycles without soft palate elevation. We tested this hypothesis with a separate logistic regression for each pattern of soft palate motion. Jaw cycles with no soft palate elevation (no-up cycles) were the statistical standard of comparison, the “quasi-control”, for each logistic regression model. The dependent variable was occurrence of soft palate elevation (yes or no) for each jaw cycle; independent variables were respiratory phase and food type.

Displacement of the Soft Palate

We calculated the displacement of the soft palate for each elevation pattern by subtracting the onset position from the peak position (vertical coordinates only). To adjust for differences among participants, displacement was normalized to the displacement during a 10-mL liquid swallow in the same participant. We analyzed differences in displacement by respiratory phase, food type, and participant for each type of jaw motion cycle and palatal elevation pattern, using mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA).

P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SPSS 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Frequency of Soft Palate Elevation

The soft palate elevated during 76% (618/812) of masticatory cycles (processing and stage II transport cycles) including 318 pull-up, 148 push-up, and 152 push-pull cycles. Elevation started at the time of minimum gape, reached its peak during jaw opening, and descended during early jaw closing. The frequency of soft palate elevation varied among participants, ranging from 33% to 100%.

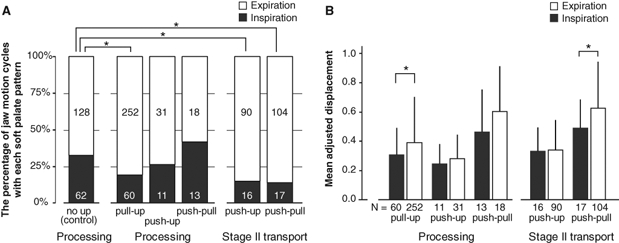

During processing cycles without soft palate elevation (no-up pattern), 33% (62/190) were initiated during inspiration. In processing cycles with pull-up elevation of the soft palate motion, however, only 19% (60/312) of jaw motion cycles started during inspiration, a 42% reduction compared with control (no-up) cycles (p < 0.001, Figs. 3A, 4A). The frequency of jaw cycles with push-up (26%, 11/42) and push-pull patterns (42%, 13/31) during inspiration did not differ significantly from control (no-up) cycles (p = 0.50 and 0.19, respectively; Fig. 4A). The overall frequency of the pull-up pattern was significantly higher when participants were eating a cookie than when they were eating the chicken (58% vs. 40%, p = 0.01), perhaps reflecting the larger percentage of processing cycles with hard food.

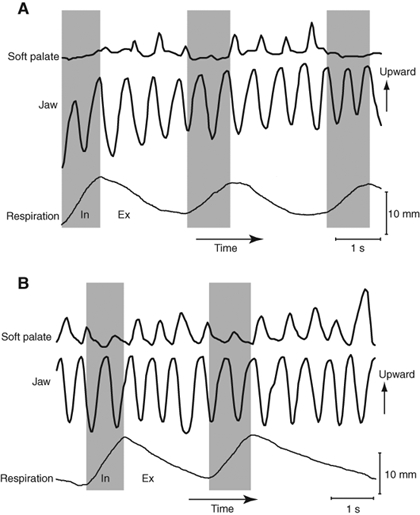

Figure 3.

Two examples of vertical jaw and soft palate movements over time with concurrent respiratory patterns in processing cycles while participants were eating a cookie. These feeding sequences were in different participants. Upward movement is shown as upward deflection on the graph. The inspiratory and expiratory phases are shown in gray and white, respectively. (A) Cyclical elevation of the soft palate was temporally linked to rhythmic jaw movement during expiration, but soft palate elevation was minimal during inspiration. (B) Soft palate elevation was temporally linked to jaw movement in every cycle. However, the amplitude of soft palate elevation was smaller during inspiration than expiration.

Figure 4.

Interaction of respiration and soft palate motion in (A) the frequency and (B) displacement of soft palate movement. (A) Stacked columns showing the percentage and number of processing and stage II transport cycles of the jaw that occurred during inspiration (gray) and expiration (white). The counts of jaw cycles with no soft palate movement (the no-up pattern) served as the statistical control for cycles with soft palate movement. During processing, jaw cycles with pull-up were significantly less frequent during inspiration (p < 0.001, logistic regression analysis). During stage II transport, cycles with push-up and push-pull were significantly less frequent during inspiration (p < 0.004). Swallow cycles are not shown, since there was no air movement during the swallow. (B) Bar graphs showing the mean (± SD) adjusted amplitude of soft palate displacement for each soft palate movement pattern and each jaw cycle type. The amplitude of pull-up soft palate displacement was significantly smaller during inspiration (dark bar) than during expiration (white bar) in processing cycles (p = 0.04, mixed-model ANOVA). During stage II transport cycles, the amplitude of push-pull displacement was significantly smaller during inspiration than during expiration (p = 0.03). Swallow cycles are not shown, since there was no air movement during the swallow. *P < 0.05 for comparison with control cycles. *P < 0.05 for inspiration vs. expiration.

In 96% of stage II transport cycles, the soft palate was pushed up by the tongue along with the food (45% push-up and 51% push-pull patterns of soft palate motion). Jaw motion cycles with push-up and push-pull elevation were 55% less likely to be initiated during inspiration than were control cycles (p < 0.004, Fig. 4A). This contrasts with processing, where push-up and push-pull cycles during inspiration did not differ in frequency from control cycles.

Displacement of the Soft Palate

In processing, jaw cycles with the pull-up pattern of soft palate elevation had a significantly smaller mean displacement during inspiration than expiration (p = 0.04, Figs. 3B, 4B). With push-up and push-pull patterns, however, soft palate displacement did not differ significantly between inspiration and expiration (p = 0.22 and 0.08, respectively). During stage II transport cycles with push-pull elevation, soft palate displacement was significantly smaller during inspiration than expiration (p = 0.03, Fig. 4B), but there was no difference in displacement between inspiration and expiration for push-up cycles, perhaps reflecting the relatively small displacement in push-up cycles. Displacement did not differ significantly by food type.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated significant effects of respiration on soft palate movement during mastication and oral food transport. In processing cycles, pull-up elevation of the soft palate (the predominant pattern) was less frequent and smaller in amplitude during inspiration than expiration. During stage II transport cycles, soft palate movement was less frequent (push-up and push-pull motion) and smaller in amplitude (push-pull only) during inspiration than expiration. These findings suggest that masticatory soft palate elevation is diminished during inspiration relative to expiration.

Pull-up of the soft palate moves it both upward and backward; this opens the fauces but narrows the velopharyngeal isthmus, potentially increasing resistance to airflow. Depression of the soft palate has the opposite effects. According to Bernoulli’s principle, the pressure exerted by a fluid varies inversely with its velocity. In the absence of muscle contraction, the pharyngeal lumen tends to collapse during inspiration, due to the negative transmural pressure gradient created by the higher velocity airflow (as in obstructive sleep apnea). This pressure gradient pulls the soft palate posteriorly, narrowing the velopharyngeal isthmus during inspiration. Contraction of the soft palate depressor muscles pulls it downward and forward, widening the velopharyngeal isthmus (Mathew, 1984; Mortimore et al., 1995; Tangel et al., 1995; Mortimore and Douglas, 1997). Fontana et al. (1992) reported that total airway resistance increases during mastication. We suggest that the increase is related to elevation of the soft palate during mastication; reducing masticatory soft palate elevation could improve patency of the velopharyngeal isthmus during inspiration.

Soft palate elevation in stage II transport is initially produced by action of the tongue squeezing food against it; this is the major mechanism of food propulsion (Franks et al., 1984; Hiiemae and Palmer, 1999). Elevation of the soft palate opens the fauces for stage II transport but narrows the pharyngeal airway, which can increase upper airway resistance. Those movements oppose the forward motions of the soft palate and tongue base that maintain pharyngeal airway patency during inspiration (Mortimore et al., 1995; Tsuiki et al., 2000; Bailey et al., 2001; Bailey and Fregosi, 2004). This may explain why both the frequency and amplitude of elevation decrease during inspiration.

While the present study clearly demonstrates changes in soft palate elevation associated with inspiration, it does not reveal underlying mechanisms. The change in motion could reflect a feed-forward mechanism originating in central respiratory centers or a feedback mechanism, depending on airway receptors that detect changes in air pressure and flow. The present study does not establish whether the reduction in elevation is due to inhibition of levator muscles or excitation of depressors; this could be resolved by combining kinematic recording with synchronous EMG. Such studies could also examine the possibility that soft palate elevator muscles are contracting even during cycles without visible motion of the soft palate.

In conclusion, masticatory soft palate elevation is reduced during inspiration. Soft palate movement is controlled by the central nervous system centers for both respiration and feeding; the control of breathing appears to have a significant effect on soft palate elevation in mastication. The fine interaction of breathing and feeding centers in control of soft palatal movement is essential to providing nutrition and preventing pulmonary aspiration.

Acknowledgments

The late Dr. Karen Hiiemae contributed immeasurably to the planning and design of this study. We thank Ms. Chune Yang for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This study was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Award R01-DC-02123 and MEXT KAKENHI (21792163).

References

- Bailey EF, Fregosi RF. (2004). Coordination of intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles during spontaneous breathing in the rat. J Appl Physiol 96:440-449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey EF, Jones CL, Reeder JC, Fuller DD, Fregosi RF. (2001). Effect of pulmonary stretch receptor feedback and CO(2) on upper airway and respiratory pump muscle activity in the rat. J Physiol 532(Pt 2):525-534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana GA, Pantaleo T, Bongianni F, Cresci F, Viroli L, Sarago G. (1992). Changes in respiratory activity induced by mastication in humans. J Appl Physiol 72:779-786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks HA, Crompton AW, German RZ. (1984). Mechanism of intraoral transport in macaques. Am J Phys Anthropol 65:275-282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiiemae KM, Palmer JB. (1999). Food transport and bolus formation during complete feeding sequences on foods of different initial consistency. Dysphagia 14:31-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launois SH, Remsburg S, Yang WJ, Weiss JW. (1996). Relationship between velopharyngeal dimensions and palatal EMG during progressive hypercapnia. J Appl Physiol 80:478-485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew OP. (1984). Upper airway negative-pressure effects on respiratory activity of upper airway muscles. J Appl Physiol 56:500-505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Hiiemae KM, Palmer JB. (2005). Cyclic motion of the soft palate in feeding. J Dent Res 84:39-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo K, Metani H, Mays KA, Palmer JB. (2008). Tempospatial linkage of soft palate and jaw movements in feeding [in Japanese]. Jpn J Dysphagia Rehabil 12:20-30 [Google Scholar]

- Mortimore IL, Douglas NJ. (1997). Palatal muscle EMG response to negative pressure in awake sleep apneic and control subjects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156(3 Pt 1):867-873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimore IL, Mathur R, Douglas NJ. (1995). Effect of posture, route of respiration, and negative pressure on palatal muscle activity in humans. J Appl Physiol 79:448-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JB, Rudin NJ, Lara G, Crompton AW. (1992). Coordination of mastication and swallowing. Dysphagia 7:187-200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenstein DO, Stanescu DC. (1986). The soft palate and breathing. Am Rev Respir Dis 134:311-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangel DJ, Mezzanotte WS, White DP. (1995). Respiratory-related control of palatoglossus and levator palatini muscle activity. J Appl Physiol 78:680-688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuiki S, Ono T, Ishiwata Y, Kuroda T. (2000). Functional divergence of human genioglossus motor units with respiratory-related activity. Eur Respir J 15:906-910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]