Abstract

A minimally invasive caries-removal technique preserves potentially repairable, caries-affected dentin. Mineral-releasing cements may promote remineralization of soft residual dentin. This study evaluated the in vivo remineralization capacity of resin-based calcium-phosphate cement (Ca-PO4) used for indirect pulp-capping. Permanent carious and sound teeth indicated for extraction were excavated and restored either with or without the Ca-PO4 base (control), followed by adhesive restoration. Study teeth were extracted after 3 months, followed by sectioning and in vitro microhardness analysis of the cavity floor to 115-µm depth. Caries-affected dentin that received acid conditioning prior to Ca-PO4 basing showed significantly increased Knoop hardness near the cavity floor. The non-etched group presented results similar to those of the non-treated group. Acid etching prior to cement application increased microhardness of residual dentin near the interface after 3 months in situ.

Keywords: dental caries, Knoop hardness, Ca-PO4 cement, bioactive cement, RCT

Introduction

Contemporary caries management focuses on lesion stabilization, the creation of an optimal environment for caries-affected tissue to heal (Peters and McLean, 2001a,b). Minimally invasive treatments, such as ultraconservative caries removal (Mertz-Fairhurst et al., 1998; Maltz et al., 2002), atraumatic restorative techniques (Frencken et al., 1994), and indirect pulp-capping procedures (Bjørndal et al., 1997), have shown that caries can be halted, and affect tissue remineralization. Remineralization of residual affected dentin can be promoted by the use of bioactive, ion-releasing base materials, e.g., glass-ionomer or resin-based calcium-phosphate cements (RCPC) (Mukai et al., 1998; Dickens et al., 2003, 2004; Exterkate et al., 2005; Ngo et al., 2006). In vitro remineralization experiments with RCPC resulted in significantly increased mineral content, documenting the capacity of RCPC to remineralize and promote healing of mineral-deficient dentin (Dickens et al., 2003; Dickens and Flaim, 2008). A subsequent in vivo proof-of-principle study (Peters et al., 2010) reported increased hardness, evaluated clinically, and increased mineral content, which was determined by elemental analysis of RCPC-treated caries-affected dentin. Based on a bone regeneration material (Chow et al., 2000), RCPC is composed of calcium-phosphates incorporated into dual-curing resins, leading to enhanced clinical handling and performance, resulting in command cure, increased strength, and dentin adhesion (Dickens et al., 2004).

The present study investigated the same specimens that were used for elemental analyses (Peters et al., 2010) for the potential clinical benefit of RCPC with respect to the restoration of Knoop hardness. With standardized caries removal procedures, the hardness was evaluated on caries-affected and sound dentin after in vivo placement of RCPC for 3 mos, followed by an adhesive restoration procedure. We tested the hypothesis that placement of RCPC on caries-affected dentin would increase the microhardness of mineral-depleted dentin over time, and confirm the elemental analysis results.

Materials & Methods

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluated the in vivo remineralization potential of Ca-PO4 base cement. Detailed information on study design, conduct, and elemental results of this IRB-approved (UM #H03-00001883; FOB-USP #126/2003) RCT has been reported elsewhere (Peters et al., 2010), in accordance with CONSORT guidelines (Moher et al., 2001).

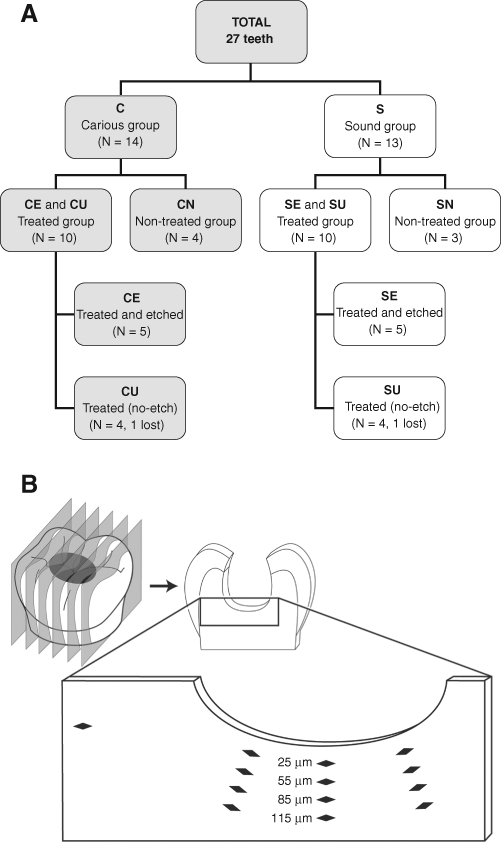

Forty-four adult patients with 87 periodontally involved carious or sound teeth indicated for extraction were included in the study. Twenty-seven carious and sound teeth (Fig. 1A) were randomly selected for previous elemental analysis (Peters et al., 2010) and evaluation of microhardness.

Figure 1.

Allocation of teeth (status/group) and location of hardness indentation in each tooth section. (A) Sample distribution. (B) Diagram of Knoop indentations at cavity floor.

In the carious group (C), unsupported enamel was removed with high-speed burs, and infected dentin was removed with polymer burs (SmartPrep-System®, SS White Burs, Inc., Lakewood, NJ, USA). In the sound group (S), standard cavities were prepared followed by instrumentation of cavity walls with polymer burs. Non-restored groups [carious, CN (N = 4); and sound, SN (N = 3)] served as control. Prior to the application of RCPC, both C and S teeth (N = 10) were randomized, by means of a random number table and concealed numbered envelopes, into 2 equal subgroups (N = 5): CE, SE with dentin pre-treatment (etched; Total Etch®, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein) and CU, SU without dentin pre-treatment (unetched). Placement of RCPC base was followed by a standard adhesive restoration. Three months later, the restored teeth were extracted. All 27 teeth were fixed, embedded, and longitudinally sectioned through the cavity (~ 3 sections/tooth, 200 µm thick) in preparation for elemental analysis and microhardness testing.

Knoop Hardness (KHN) Analysis

Knoop hardness testing was carried out with the use of a Clark Microhardness Tester (model CM-700AT, Sun-Tec Corp, Novi, MI, USA) with a Knoop diamond indenter, set at a 10-g of load for 10 sec (Craig et al., 1959). Knoop hardness (KHN) was measured along 3 lines in each section (N = 75), starting at 25 µm from the cavity floor toward the pulp. These lines were widely separated and placed perpendicularly to the cavity-base boundary. Four measurements were taken along each line, 30 µm apart up to 115 µm in depth (Fig. 1B). Microhardness measurements were obtained from the same sections and close to previously assessed locations for elemental analysis (Peters et al., 2010). As an internal control, a fourth measurement was obtained in sound dentin, distant from the lesion, for both treated carious and sound groups. In total, 949 data points were obtained, 442 in sound and 507 in caries-affected teeth, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in ‘random coefficient models’, adjusted for inherent variability of dentin (inter- and intra-tooth biologic variation, lesion depth). We used a linear mixed model to fit Knoop hardness values at each depth for each section within a tooth. The slope was measured (i.e., change in KHN with depth). A sample size of 12 sections per treatment enabled us to detect differences in slopes of 0.0365 with 90% power at alpha = 0.05.

Effects of treatment on KHN data (means) were estimated separately for sound and carious teeth by Random Coefficient Models (Verbeke and Molenberghs, 2000). Models included fixed effects of treatment, depth, and treatment-by-depth interactions. Effect of depth was modeled with both linear and quadratic trends to allow for curved relationships as depth increased. Linear and quadratic effects of depth were allowed to differ by treatment. The model for KHN data included random intercepts and slopes for each tooth, allowing characteristic KHN values and fitted curves to vary randomly between teeth. Although this proof-of-principle study is essentially exploratory in nature, we used Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons within each depth. All statistical analyses were carried out with the Proc Mixed procedure in SAS (SAS Institute, 2004).

Results

Microhardness

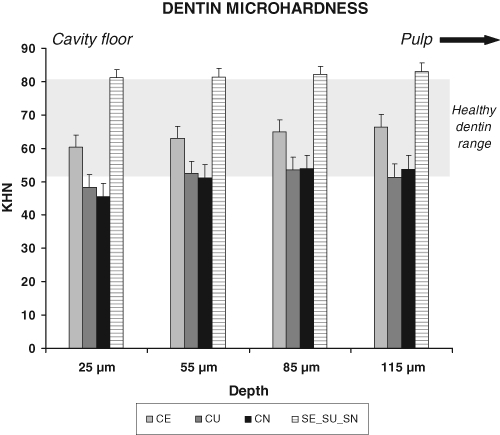

KHN values are shown at different depths for carious (CN, non-restored; CE, etched; CU, unetched) and pooled sound groups (SE_SU_SN) (Fig. 2). The shaded area represents the KHN range of healthy dentin.

Figure 2.

Microhardness of the cavity floor (p-values in the Table). KHN in caries-affected or sound dentin measured at 25, 55, 85, and 115 µm from the interface into dentin. Connection of datapoints per group by a line provides the regression lines for each group from 25 µm up to 115 µm into dentin toward the pulp. CN (N = 12 sections, with N = 36 datapoints at each depth): Values ranged from 45.6 KHN (close to the interface) up to 53.9 and 53.6 KHN (at 85 µm and 115 µm, respectively). CE (N = 15 sections, with N = 45 datapoints at each depth): started at 60.4 KHN (close to the interface) and increased up to the deepest point (66.3 KHN at 115 µm). CU (N = 12 sections, with N = 36 datapoints at each depth): Values ranged from 49.4 KHN (close to the interface), increasing to 53.4 KHN (at 85 µm) and slightly decreasing to 52.3 KHN (at 115 µm). SE_SU_SN (pooled; N = 34 sections, with N = 102 datapoints at each depth): Sound specimens, whether treated or not, showed similar KHN levels of approximately 82 KHN at each depth (range, 81.1 to 83.0 KHN from depths of 25 to 115 µm). Close to the interface, KHN levels of CE were 32% higher than those of CN, but still 26% lower than those of the pooled sound group.

Corresponding p-values are provided for multiple comparisons between groups, either within sound or caries-affected dentin or between carious and sound pooled groups (Table).

Table.

KHN Values: p-values* for Comparison of Groups

| KHN |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison |

p-values |

|||

| Depth | 25 µm | 55 µm | 85 µm | 115 µm |

| Caries-affected | ||||

| CEvs. CN | 0.0164a | 0.0452 | 0.0642 | 0.0478 |

| CUvs. CN | 0.4918 | 0.8136 | 0.9369 | 0.8176 |

| CEvs. CU | 0.0509 | 0.0595 | 0.0472 | 0.0256 |

| Sound | ||||

| SEvs. SN | 0.3641 | 0.4383 | 0.4440 | 0.3787 |

| SUvs. SN | 0.3910 | 0.7521 | 0.7652 | 0.4228 |

| SEvs. SU | 0.9560 | 0.5949 | 0.5891 | 0.9282 |

| Pooled groups | ||||

| SE_SU_SN vs. CE | 0.0002a | 0.0005a | 0.0012a | 0.0018a |

| SE_SU_SN vs. CU | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a |

| SE_SU_SN vs. CN | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a | < 0.0001a |

Significant: p ≤ 0.0166 by Bonferroni correction within caries-affected and sound teeth comparisons.

The p-values for comparisons of microhardness (KHN) data in caries-affected [CE (etched), CU (unetched), CN (non-restored)] and sound [SE (etched), SU (unetched), SN (non-restored)] dentin groups, as well as between caries-affected and pooled sound (SE_SU_SN) dentin groups. After Bonferroni correction within caries-affected and sound teeth comparisons, no statistically significant difference in KHN was observed between CE and CU, or CU and CN, or among sound subgroups (SE, SU, or SN) at the cavity floor or over deeper areas. A significantly higher KHN was observed at 25 µm between CE and CN. The pooled sound group presented significantly higher levels of KHN at all depths in comparison with each caries-affected group.

At the different depths, values of sound teeth (SE, SU, SN) were similar, and thus were pooled per depth for comparative analyses (SE_SU_SN).

The sound pooled group (SE_SU_SN) presented neither linear nor quadratic effects over depth. CE showed neither linear nor quadratic effects, indicating that values were similar throughout underlying dentin at all depths. CU presented significant linear and quadratic effects (p = 0.0191 and 0.0425, respectively), while for CN those effects were highly significant (p = 0.0001 and < 0.0071, respectively). This means that, for both CU and CN, values increased from the interface toward deeper dentin, presenting both straight linear increase as well as quadratic curved effects, i.e., slightly lower values near the interface, leveling off at deepest depths.

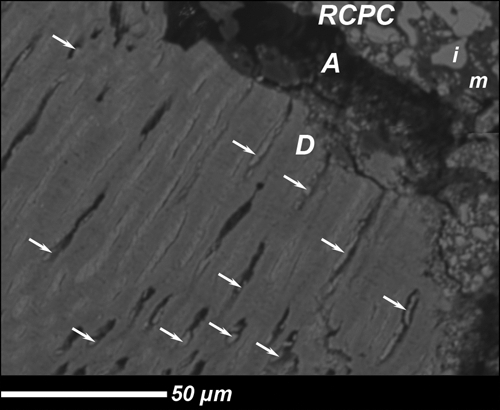

Mineral deposits were observed in tubule lumina (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Representative SEM of the dentin/RCPC interface after 3 mos in vivo. RCPC: Resin Calcium-Phosphate Cement: m = matrix, i = inorganic phase. A, artifact due to specimen fixation; D, dentin; arrow, crystals obliterating tubules.

Discussion

The repair potential of carious dentin has been demonstrated in studies supporting the stepwise excavation of deep caries lesions (Bjørndal et al., 1997). The ability of a base material to assist in remineralization and enhance tissue repair would be clinically beneficial. This study focused on the ability of RCPC to re-establish hardness of affected dentin. Clinical efficacy and mineral uptake after 3 mos of intra-oral service with this ion-releasing base have been previously reported: The clinically assessed dentin floor was hard, showing clinical signs of remineralization after 3 mos (Peters et al., 2010). Calcium and phosphorus were re-incorporated into treated caries-affected dentin, reaching sound dentin values at 30-µm depth (Peters et al., 2010). Present microhardness measurements were taken adjacent to the elemental analysis locations. The first reliable indentation for assessment of KHN was performed at 25 µm (Hossain et al., 2003) from the cavity floor, to account for edge-effects and the presence of relatively soft, superficial caries-affected dentin in carious specimens. Since the distance between measuring points was 30 µm, interference of deformation areas caused by nearby indentations was avoided (Miyauchi et al., 1978).

Carious dentin microhardness varies from 14 to 38 KHN, while sound dentin values are expected to range from 53 to 80 (Craig et al., 1959; Banerjee et al., 1999). Pooled sound dentin (SE_SU_SN) microhardness measured in this study ranged from 81 to 83 KHN. This is slightly higher than the 63 to 80 KHN reported for cavity depth (1-1.5 mm into dentin) (Miyauchi et al., 1978; Meredith et al., 1996). The limited sample size of these two studies may have contributed to the lower values reported. The hardness of non-treated caries-affected dentin (CN: 45 KHN at 25-µm depth), measured after caries removal with self-limiting polymer burs (Boston, 2003), was also slightly higher than the range reported in the literature (Peters et al., unpublished observations). While greater distance of first measurement from the cavity floor might have contributed to slightly higher values, difference in specimen preparation (Kinney et al., 2003; Angker et al., 2004) may also have played a role. The dentin samples in this study were prepared for electron probe microanalysis, and thus, were fixed and dried. Higher and more uniform microhardness values have been reported for dried vs. wet carious dentin (Pugach et al., 2009), supporting our data range. Moreover, all samples underwent the same processing steps, validating within-study comparisons.

Among the carious groups, both CN (non-restored) and CU (unetched) groups presented similar results according to KHN levels, i.e., both showed linear and quadratic effects over depth. CE (etched) presented neither linear nor quadratic effects and was higher than CN at 25 µm. Although the predicted curve for CE was at a higher level than both other carious groups, no statistical differences were found between CE and CU or CN. In comparison with the pooled sound teeth, the 3 carious groups presented significantly lower values. This is in contrast to previously published data from the same study, where mineral content was higher for both treated carious groups (CE, CU), when compared with the non-treated carious group (CN), reaching the mineral level of sound dentin at 30-µm depth (Peters et al., 2010).

In general, microhardness is associated with mineral content (Miyauchi et al., 1978; Pugach et al., 2009). However, while both KHN and EPMA methods relate to mineralization, they are not fully comparable, but rather are complementary, due to differences between these methodologies (Kinney et al., 1996a), observations on dentin structure (Landis, 1995; Kinney et al., 2003), and mechanical properties (Ogawa et al., 1983; Kinney et al., 1996b; Banerjee et al., 1999). While mineral content analysis provides data for specific components in dentinal tissue, microhardness testing provides an averaged number for this non-uniform composite substrate (Currey and Brear, 1990; Kinney et al., 1996b) and leads to a non-linear relationship between microhardness and mineral content in specific situations. Mineralization patterns that differ from the usual organization and orientation of minerals might lead to different mechanical properties of substrates (Landis, 1995; Kinney et al., 2003).

According to the structure of dentin, microhardness may be related to 3 different forms of mineralization, represented as: (a) plate-shaped crystals within tubule lumina, as shown in our specimens; (b) uniform mineral distribution in peritubular and intertubular dentin; and (c) intra- and interfibrillar mineral in collagen. Compared with sound dentin, the numbers and concentrations of plate-shaped crystals are higher within tubules in subtransparent areas of demineralized dentin that border sound dentin and often show tubule obliteration (Ogawa et al., 1983; Banerjee et al., 1999). In contrast, microhardness of this zone is lower than that of sound dentin, contradicting a correlation between mineral content and microhardness (Ogawa et al., 1983). In other areas, correlation of mineral content and microhardness is linear. Since microhardness of dentin reflects the average of a heterogeneous substrate, it is suggested that mineral deposits in tubule lumina do not necessarily contribute to increased hardness.

Recently, more detailed evaluation of inter- and peritubular dentin by nanohardness revealed that intertubular dentin in sound teeth, although presenting lower hardness values than peritubular dentin, is responsible for overall dentin hardness (Kinney et al., 1996b). Hardness of peritubular dentin is also important, since it is associated with the initial demineralization process (Pugach et al., 2009). Moreover, although from 70 to 75% of mineral may be extrafibrillar to collagen structures, if intrafibrillar remineralization is absent, the correlation between hardness and mineral content vanishes (Kinney et al., 2003). The relationship between microhardness and mineral content is complex, not yet fully understood, and warrants further detailed investigation.

Our specimens enabled us to compare microhardness data with previous EPMA data of closely located areas in the same samples. However, the microhardness results did not follow our previously reported mineral data. Although significant increases were measured, microhardness was re-established to only 74% of the level of sound dentin. This apparent lack of correlation corroborates the results of an earlier study where, after 3 mos of remineralization, higher calcium concentrations were found in shallow lesion areas, while only deeper areas showed increased microhardness (Fusayama, 1979).

Acid-etching opens dentin tubules and may assist in the mineralization of intertubular and peritubular dentin close to the interface. Since CE presented higher values than CN at the first datapoint close to the interface, acid-etching may have contributed to faster re-establishment of microhardness, with re-incorporation of minerals dispersed into intertubular dentin. Long-term studies may provide insight into remineralization dynamics, rate of mineral uptake, and hardness increase.

This study showed that, after 3 mos, treated caries-affected dentin, although being remineralized, did not regain microhardness to the level of sound dentin. Remineralization of caries-affected dentin, being a healing process, might precede re-establishment of previous microhardness levels. Remineralization is defined as restoration of lost mineral constituents. According to our data, after 3 mos under a bioactive base, dentin was remineralized, i.e., showing “normal” levels of minerals (Peters et al., 2010), while the microhardness was not re-established to normal levels. We speculate that dentin repair steps take place in different time intervals, with mineral uptake being the first step, followed by intertubular and intrafibrillar collagen remineralization, leading to re-established microhardness. Therefore, long-term clinical evaluation is warranted to determine the full dentin repair potential of RCPC base.

Acid-etching before placement of RCPC base facilitated the remineralization process, since the microhardness of dentin close to the interface was significantly increased with this pre-treatment; unetched dentin under RCPC also showed a strong trend (p = 0.0509), but it was no longer significant after Bonferroni correction at the 0.05 level of confidence.

In summary, after 3 mos in vivo, the application of RCPC base resulted in increased microhardness of the cavity floor when applied to acid-etched caries-affected dentin, partially confirming the posed hypothesis. Longer periods of evaluation might reveal continued remineralization dynamics and re-establishment of microhardness to the level of sound dentin.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. R.B. Rutherford (U-Washington, Seattle) for contributing to the study design; Drs. T.J.E. Barata, T.C. Fagundes, and R.L. Navarro (U-São Paulo, Bauru) for their excellent clinical work; and Kathy Welch (UM-CSCAR) for statistical assistance.

Footnotes

This study was supported by Dentigenix/Ivoclar-Vivadent AG (Schaan, Liechtenstein), by U-Michigan, and by CAPES #BEX3404-8 (Brazil). Co-author SHD developed RCPC at the Paffenbarger Research Center, American Dental Association Foundation. Her research was supported by NIDCR Grant No. DE013298. She was not involved in data collection or analysis, but contributed to manuscript writing.

Preliminary data were presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the American Association for Dental Research, Orlando, FL, USA (Abstr #482).

References

- Angker L, Nijhof N, Swain MV, Kilpatrick NM. (2004). Influence of hydration and mechanical characterization of carious primary dentine using an ultra-micro indentation system (UMIS). Eur J Oral Sci 112:231-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Sherriff M, Kidd EA, Watson TF. (1999). A confocal microscopic study relating the autofluorescence of carious dentine to its microhardness. Br Dent J 187:206-210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørndal L, Larsen T, Thylstrup A. (1997). A clinical and microbiological study of deep carious lesions during stepwise excavation using long treatment intervals. Caries Res 31:411-417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boston DW. (2003). New device for selective dentin caries removal. Quintessence Int 34:678-685 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow LC, Hirayama S, Takagi S, Parry E. (2000). Diametral tensile strength and compressive strength of a calcium phosphate cement: effect of applied pressure. J Biomed Mater Res 53:511-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig RG, Gehring PE, Peyton FA. (1959). Relation of structure to the microhardness of human dentin. J Dent Res 38:624-630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currey JD, Brear K. (1990). Hardness, Young’s modulus and yield stress in mammalian mineralized tissues. J Mater Sci Mater Med 1:14-20 [Google Scholar]

- Dickens SH, Flaim GM. (2008). Effect of a bonding agent on in vitro biochemical activities of remineralizing resin-based calcium phosphate cements. Dent Mater 24:1273-1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens SH, Flaim GM, Takagi S. (2003). Mechanical properties and biochemical activity of remineralizing resin-based Ca-PO4 cements. Dent Mater 19:558-566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens SH, Kelly SR, Flaim GM, Giuseppetti AA. (2004). Dentin adhesion and microleakage of a resin-based calcium phosphate pulp capping and basing cement. Eur J Oral Sci 112:452-457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exterkate RA, Damen JJ, ten Cate JM. (2005). Effect of fluoride-releasing filling materials on underlying dentinal lesions in vitro. Caries Res 39:509-513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frencken JE, Songpaisan Y, Phantumvanit P, Pilot T. (1994). An atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) technique: evaluation after one year. Int Dent J 44:460-464 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusayama T. (1979). Two layers of carious dentin; diagnosis and treatment. Oper Dent 4:63-70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M, Nakamura Y, Tamaki Y, Yamada Y, Jayawardena JA, Matsumoto K. (2003). Dentinal composition and Knoop hardness measurements of cavity floor following carious dentin removal with Carisolv. Oper Dent 28:346-351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JH, Balooch M, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW, Jr, Weihs TP. (1996a). Atomic force microscope measurements of the hardness and elasticity of peritubular and intertubular human dentin. J Biomech Eng 118:133-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JH, Balooch M, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW, Jr, Weihs TP. (1996b). Hardness and Young’s modulus of human peritubular and intertubular dentine. Arch Oral Biol 41:9-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney JH, Habelitz S, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. (2003). The importance of intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen on the mechanical properties of dentin. J Dent Res 82:957-961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis WJ. (1995). The strength of a calcified tissue depends in part on the molecular structure and organization of its constituent mineral crystals in their organic matrix. Bone 16:533-544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltz M, de Oliveira EF, Fontanella V, Bianchi R. (2002). A clinical, microbiologic, and radiographic study of deep caries lesions after incomplete caries removal. Quintessence Int 33:151-159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith N, Sherriff M, Setchell DJ, Swanson SA. (1996). Measurement of the microhardness and Young’s modulus of human enamel and dentine using an indentation technique. Arch Oral Biol 41:539-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz-Fairhurst EJ, Curtis JW, Jr, Ergle JW, Rueggeberg FA, Adair SM. (1998). Ultraconservative and cariostatic sealed restorations: results at year 10. J Am Dent Assoc 129:55-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi H, Iwaku M, Fusayama T. (1978). Physiological recalcification of carious dentin. Bull Tokyo Med Dent Univ 25:169-179 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. (2001). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 134:657-662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai Y, Tomiyama K, Okada S, Mukai K, Negishi H, Fujihara T, et al. (1998). Dentinal tubule occlusion with lanthanum fluoride and powdered apatite glass ceramics in vitro. Dent Mater J 17:253-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo HC, Mount G, McIntyre J, Tuisuva J, Von Doussa RJ. (2006). Chemical exchange between glass-ionomer restorations and residual carious dentine in permanent molars: an in vivo study. J Dent 34:608-613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Yamashita Y, Ichijo T, Fusayama T. (1983). The ultrastructure and hardness of the transparent layer of human carious dentin. J Dent Res 62:7-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MC, McLean ME. (2001a). Minimally invasive operative care. I. Minimal intervention and concepts for minimally invasive cavity preparations. J Adhes Dent 3:7-16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MC, McLean ME. (2001b). Minimally invasive operative care. II. Contemporary techniques and materials: an overview. J Adhes Dent 3:17-31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters MC, Bresciani E, Barata TJ, Fagundes TC, Navarro RL, Navarro MF, et al. (2010). In vivo dentin remineralization by calcium-phosphate cement. J Dent Res 89:286-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugach MK, Strother J, Darling CL, Fried D, Gansky SA, Marshall SJ, et al. (2009). Dentin caries zones: mineral, structure, and properties. J Dent Res 88:71-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2004). SAS/STATA v.10.0 SE. Cary, NC: SAS Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. (2000). Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer-Verlag Inc. [Google Scholar]