Abstract

Purpose

To develop a patient self-completed questionnaire from the items of the Brief Core Set Questionnaire for Breast Cancer (BCSQ-BC) and to investigate the prevalence of specific dysfunctions throughout the course of cancer and treatments.

Methods

From January 2010 to February 2011, 96 breast cancer patients were evaluated with BCSQ-BC developed for clinical application of International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Quality of life and upper limb dysfunction using disabilities of arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) were assessed. Content validity was evaluated using correlations between BCSQ-BC and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ and DASH scores. Construct validity was computed using exploratory factor analysis. Kappa statistics were computed for agreement between test-retest ICF data. The level of significance and odds ratios were reported for individuals with early post-acute and long-term context and with total mastectomy and breast conservative surgery.

Results

There was consistently good test-retest agreement in patient-completed questionnaires (kappa value, 0.76). Body function, activity and participation subscales are significantly related with EORTC QLQ and DASH. Problems with activity and participation were strongly associated with physical functional domains of EORTC QLQ (r=-0.708, p<0.001) and DASH (r=0.761, p<0.001). The prevalence of dysfunctions varied with type of surgery and time after cancer. Immobility of joint (15% vs. 7%) and lymphatic dysfunction (17% vs. 3%) were indexed more frequently in extensive surgery cases than in conservative surgery. Muscle power (16% vs. 8%), exercise tolerance functions (12% vs. 4%) and looking after one's health (10% vs. 2%) were impaired within 1 year after surgery, while sleep dysfunction (8% vs. 14%) was a major problem over 1 year after surgery.

Conclusion

The BCSQ-BC identifies the problems comprehensively in functioning of patients with breast cancer. We revealed the interaction with the ICF framework adopting a multifactor understanding of function and disability.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, Function, Rehabilitation, Survivors

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide [1]. The development of new chemotherapeutic agents and regimens for breast cancer has contributed to reduced risk of recurrence and prolonged patient's survival. Therefore, a significantly increased number of cancer patients now spend a large proportion of their lives coping with physical, psychological, and social impairments [2]. Impairments in body functions and body structures including shoulder pain, limitation of range of motion [3], or lymphedema [4] can negatively affect the individuals' self-image [5], the relationship with the partner and can lead to social isolation [3,4,6]. Over the last years, there has been increasing interest and awareness in the functional impact of cancer treatment on the patient and health-related quality of life has now become a secondary endpoint in the assessment of outcome various scales based on clinical examination have been reported [7].

To optimize interventions aimed at maintaining functioning and minimizing disability, a proper understanding of the patient's functioning and health status is needed. The different aspects of functional outcomes of breast cancer survivors could be evaluated by a wide variety of assessment tools. Clinical observations combined with imaging or laboratory findings can assess the functioning in a rather standardized and reproducible way. On the contrary, the aspects of daily living can be obtained more easily through patient-administered questionnaires. Patient-administered questionnaires collect the subjective patient's perspective directly and without any interpretation through health professional assessment [8]. Even though there are several breast cancer specific questionnaires [9,10], there is no gold standard and no widely acceptable indicator of functional outcome that applies across different health professionals, continents and health care systems.

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) of the World Health Organization (WHO) provides a useful framework for classifying the components of health and consequences of a disease [11]. The ICF stands alongside the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10). The ICD-10 classifies medical diagnoses, and the ICF classifies patient functioning. The ICF is based on a comprehensive biopsycho-social framework, including changes in body structures and body functions, the patient's ability to participate in everyday life situations and the influence of environmental and personal factors [9]. However, since the ICF as a whole is composed of more than 1,400 categories, it is not feasible for use in clinical practice. To facilitate the implementation of the ICF into clinical practice, ICF Core Sets for a number of health conditions [12] including breast cancer have been developed. The current version of the Comprehensive ICF Core Set for Breast Cancer includes 80 ICF categories and from this a smaller subset with 40 categories was proposed [13]. The ICF is a coding system of functioning items as the basic classification unit, however, it would be appropriate tool to form the basis for developing an instrument to evaluate the functioning decrements in breast cancer survivors. The contents of the ICF categories on the basis of a patient administered questionnaire have an advantage of unified approach for measuring function. Not only a part of body function but also a comprehensive function can be evaluated by the questionnaires with systemic framework based on the ICF Core Set.

We developed a patient self-administered questionnaire from the items of the brief core set for breast cancer (BCSQ-BC). We then assessed the reliability and content validity of the BCSQ-BC in patients with breast cancer. Dysfunction during the initial phase of diagnosis and definitive treatment planning are different from those that may arise from other phases [14], so we identified and analyzed several common dysfunctions according to the course of cancer treatment using this comprehensive functional assessment, BCSQ-BC.

METHODS

Setting and participants

From January to December 2010, we recruited participants among survivors who were referred after breast cancer surgery at our hospitals and had been followed up at a rehabilitation clinic. All participants were women aged 18 years old or over. Patients with other previously diagnosed cancers, and who were not literate were excluded. The BCSQ-BC was included as part of our cohort study [15]. Demographic and personal characteristics such as age, current marital status, level of education, economic status, and occupation were recorded using self-report questionnaires. Breast cancer and related medical variables included type of surgery and time after surgery. All participants were fully informed regarding study participation and provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (ICF IRB no: B-1009/054-003).

Measures

BCSQ-breast cancer

The ICF Core Set for breast cancer is the selection of relevant items in ICF categories and not a questionnaire. The BCSQ-BC was created using the Brief ICF Core Set for breast cancer, it consists of 40 questions about problems in the last 30 days (Table 1). It can assess the degree of problem and whether a problem was caused by something other than breast cancer. Section 1 asks about 'body structures and body functions (a problem or impairment with a part of your body, which means you have trouble doing something which you want to do)', section 2 about 'problems with activity and participation (a problem or difficulty with activity and social participation)' and section 3 about 'environmental factors (how much certain factors in your living environment have either helped or hindered your progress since your diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer)'. In sections 1 and 2 patients grade their problems as none (1), mild (2, at a level you can tolerate, occurs rarely), moderate (3, sometimes interferes with your day to day life, happens occasionally), severe (4, partly disrupts your day to day life, occurs frequently), or complete (5, totally disrupts your life, affects you every day). In section 3 they grade on a -4 to +4 scale ranging from complete hindrance to complete help. Then we produced total score and 4 subscales: body function score, body structure score, activity and participation score and environmental score. Subscale scores were the sum of the grades in the items of each section.

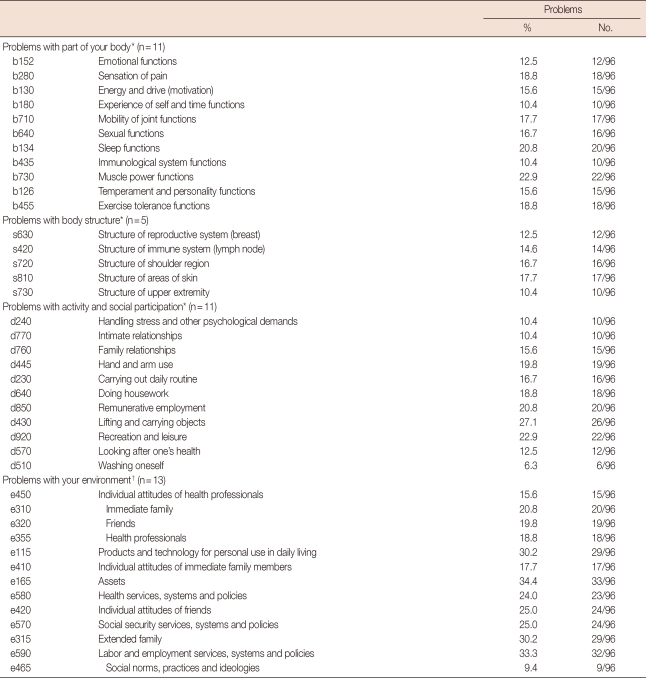

Table 1.

Overall results for the 96 patients completing the Brief ICF questionnaire

ICF=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.

*Moderate, severe, and complete grades; †Hindrance and neither hindrance or help.

Health-related quality of life

Quality of life was assessed using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30 (EORTC-C30) questionnaire. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a well-known instrument for measuring quality of life in cancer survivors; it contains 30 items that measure five functional abilities, global quality of life, and several cancer-related symptoms. A final item evaluates the perceived economic consequences of the disease. In addition, a global health status/quality of life score can be computed. This consists of two items that assess the global health status and the global quality of life. According to the guidelines provided by the EORTC, all scores of the QLQ-C30 were transformed linearly, so that all scales range from 0 to 100. On the function scales, higher scores represent a higher level of functioning. On the symptom scales/items, a higher score represents a higher level of symptoms or problem. Participants answered the questionnaires with a trained researcher [16].

Upper limb dysfunction (ULD)

Shoulder disability was measured by a validated Korean version of the widely used "disability of the arm, shoulder, and hand" (K-DASH) questionnaire [17], which is used to measure the functional status and symptoms associated with different degrees and levels of upper extremity disability. The DASH questionnaire consists of 30 items, each of which has five possible responses [18,19]. Twenty-one items ask about the degree of difficulty in performing activities of daily living (DASH-ADL), six items ask about symptoms (DASH-symptom), and the remaining three items ask about psychosocial impact (DASH-social). The DASH-global score, which includes these three domains, was considered to indicate the overall disability caused by ULD.

Analyses

The test-retest reliability was analyzed by administering the BCSQ-BC once again to the same patients 2 weeks later. Kappa statistics were computed for agreement between test-retest patient-complete ICF data. Kappa values above 0.6 represent 'good' agreement, with values above 0.80 being 'very good.' Factor analysis, the approach commonly used to reflect construct validity, was performed using the principle components method with the varimax rotation technique. Meanwhile, Kerser-Meyer-Olkin and Bartlett's test of Sphericity were carried out to evaluate the sampling adequacy for factor analysis. To determine the content validity of the BCSQ-BC, 2 analyses were carried out. Pearson's coefficient measured the amount of association between BCSQ-BC and EORTC QLQ subscale/domain scores. It was expected that all scales of the BCSQ-BC would have a negative correlation with the EORTC functional abilities. BCSQ-BC scales that mainly included the use of upper extremities should correlate substantially with the DASH scores.

The levels of significance and odds ratios (OR) for experiencing each of these functional problems were reported for individuals with early post-acute and long-term context and with conservative surgery and extensive surgery, with significant problems on ICF items, with a moderate (3), severe (4), or complete (5) score being regarded as significant for sections 1 and 2 and a hindrance/neither hindrance or help (-4 to 0) score being regarded as significant for section 3.

To identify differences in functioning between early post-acute and long-term context, while controlling for other confounders, logistic regression models were performed in an exploratory data analysis. Each of the dichotomous ICF categories was used as dependent variables in separate models. The age, current marital status, level of education, economic status, and occupation and type of adjuvant treatment were used as co-variables. SPSS software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Two-tailed p-values<0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Of 105 patients we contacted, 96 satisfied of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Nine women were excluded from the analysis because of refusal to participate in this study. Age at diagnosis ranged from 30 to 73 years (mean±standard deviation, 50.1±9.8 years). Most patients were married (93%), 77% had at least high school education, and 42.1% worked full- or part-time. The mean elapsed time from breast cancer surgery to participation was 15.4±12.9 months (1-60 months). According to the time after surgery, 53 patients (54.1%) were evaluated at less than 1 year after surgery. Forty-three patients (43.9%) were evaluated at more than 1 year after surgery. In addition, the patients were categorized according to surgical procedure, 44 patients (45.8%) underwent conservative surgery and 52 patients (54.2%) underwent extensive surgery.

Reliability

Of these 25 (33%) attended clinic for interview and also completed the ICF questionnaire (before clinic), while 22 (29%) also completed a repeat ICF questionnaire (after the first questionnaire). Though numbers are small there was consistently good test-retest agreement in patient-completed questionnaires before and after clinic, with median kappa values of 0.76 (0.69-0.85).

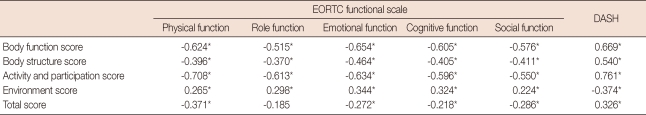

Content and construct validity

The content validity was assessed by analyzing the relationship between ICF subscales and total score and EORTC domains and DASH (Table 2). Problems with activity and participation were strongly associated with physical functional domains of EORTC and DASH. Body function, activity and participation subscales are significantly related with EORTC and DASH. Problems with activity and participation were strongly associated with physical functional domains of EORTC (r=-0.708, p<0.001) and DASH (r=0.761, p<0.001). ICF environmental problems were most prevalent among all categories of ICF, but they were weakly correlated with EORTC physical functional domains (r=0.265, p<0.001). Emotional functioning was significantly correlated with some environmental factors (range for spearman r being from 0.309 to 0.418) such as individual attitudes of health professionals, friends, health professionals, products and technology for personal use in daily living, health services, individual attitudes of friends, extended family, labor and employment services, systems and policies and social norms, practices and ideologies (data not shown).

Table 2.

Association of Brief ICF items with EORTC functional subscales and DASH

Values are Pearson correlation coefficients.

ICF=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; EORTC=European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; DASH=disabilities of arm, shoulder and hand.

*p<0.001.

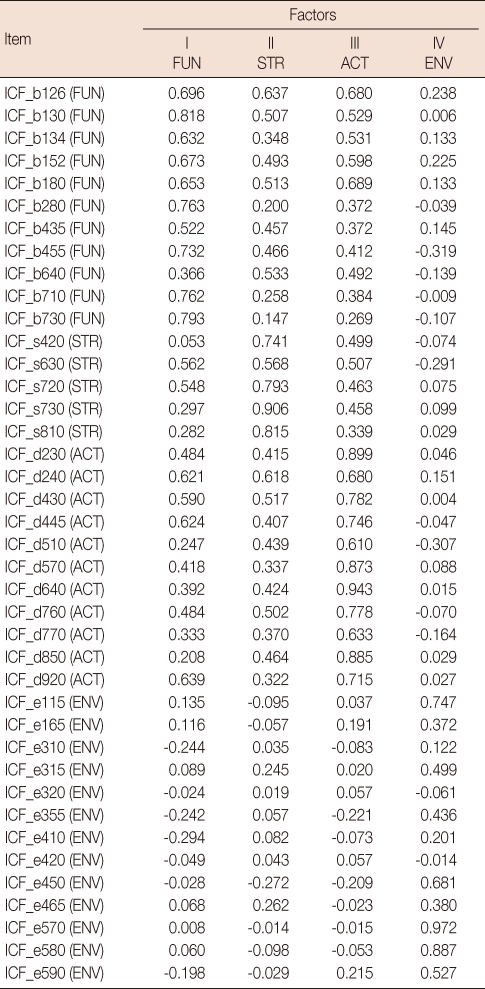

Factor analysis was conducted to test construct validity. The Kerser-Meyer-Olkin was 0.793 which was greater than 0.7, indicating an adequate correlation for factor analysis. Meanwhile, Barlett's test of Sphericity was significant with the chi-square test (351)=1,424.979 (p<0.001). Principle component analysis identified 4 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining 63.22% of the variance. The rotated component matrix is presented in Table, and 4 factors were extracted using the cutoff point of 0.4 as the criterion. Items loading on 2 factors were determined by the heavier loading point (Table 3).

Table 3.

Factor analysis of the breast ICF Core Set questionnaire: factor loading matrix by items

Varix/principal, factor loading≥0.40.

ICF=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; FUN=body function; STR=body structure; ACT=activity and participation; ENV=environmental factor.

Prevalence of dysfunction

The BCSQ-BC was generally completed. There were no notable ceiling or floor effects arising from the results of the Brief ICF questionnaire. The percentage with no problems (sections 1 and 2) or complete help (section 3) ranged from 6.3% and 62.5% between items, median 40.2% (Table 1) while the percentage with 'significant' problems (i.e., moderate, severe or complete for sections 1 and 2 or 'lack of help' including hindrance or neutral for section 3) ranged from 6.3% to 34.4%. The results emphasize problems particularly in 'muscle power functions' (22.9%) for body functions and 'lifting and carrying objects' (27.1%) for activities and participation. Significant problems on ICF environmental factors were hindrance from assets (34.4%) and labor and employment services (33.3%). A minority had 'significant' problems, most notably for washing (6.3%).

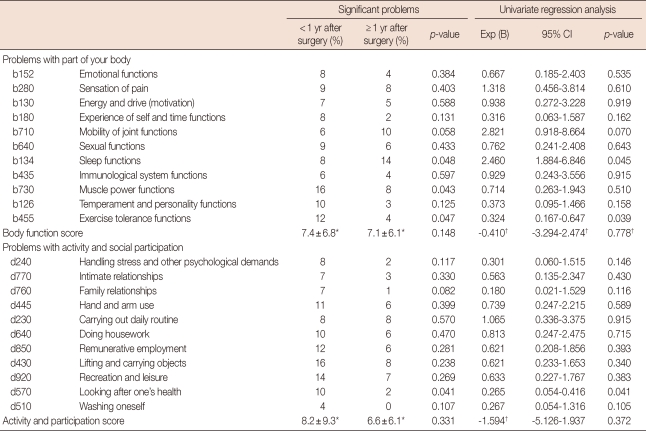

The prevalence of dysfunctions varied with type of surgery. Immobility of joint (15% vs. 7%, p=0.046) and lymphatic dysfunction (17% vs. 3%, p=0.035) were indexed more frequently in extensive surgery cases than in conservative surgery. Muscle power (16% vs. 8%, p=0.043), exercise tolerance functions (12% vs. 4%, p=0.047) and looking after one's health (10% vs. 2%, p=0.041) were mainly impaired in patients evaluated within 1 year after surgery, while sleep dysfunction (8% vs. 14%, p=0.048) was a major problem in patients evaluated over 1 year after surgery (Table 4). After adjusting the covariables such as age, current marital status, level of education, economic status, and occupation and type of adjuvant treatment, the prevalence of sleep disorder in the patients evaluated over 1 year after surgery showed a 2-fold higher risk (OR, 2.46; p=0.045).

Table 4.

Comparison of significant problem between the patients evaluated less than 1 year and more than 1 year after surgery and univariate regression analysis

Exp (B)=exponentiation of the B coefficient; CI=confidence interval.

*Comparison of subscale (body function score and activity and participation score) between groups with Wilcoxon rank sum test; †β correlation coefficient from univariate linear regression analysis after adjusting age, current marital status, level of education, economic status, and occupation and type of adjuvant treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study, to our knowledge, is the first clinical application of the breast ICF Core Set as a patient self-administered questionnaire to characterize dysfunctions in patients with breast cancer. To do this application, we developed a simple questionnaire which can be applied as a comprehensive and standardized outcome measure and not just confined to a clinical-rating scale. We found it to be a measure with good reliability and validity by means of which the main dysfunctions were confirmed throughout the course of cancer treatment. Muscle power, exercise tolerance functions and looking after one's health were mainly impaired in patients evaluated within 1 year after surgery, while sleep dysfunction was a major problem in patients evaluated over 1 year after surgery.

Although there are many health-related quality of life [9,10] and functional outcome assessment instruments in cancer, the BCSQ-BC is different in that it assessed not only changes in body structures and body functions, but also the patient's ability to participate in everyday life situations and the influence of environmental factors systemically [12] based on the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [11].

The problems and rehabilitation categories in the previous studies [20,21] did not provide a comprehensive or standardized understanding of functioning in the cancer survivors. Lehmann et al. [20] identified the needs of a cancer population and categorized the functional limitations into psychologic distress, general weakness, dependence in activities of daily living, pain, difficulties with balance in ambulation, housing, neurologic deficits, family support, and work-related problems and finances (in decreasing order of frequency). Whelan et al. [21] summarized the symptoms of cancer patients including fatigue, worry and anxiety, sleep disruption, and pain. Recently, Cheville et al. [22] subcategorized the impairments of patients with metastatic breast cancer into lymphedema, neurogenic weakness, sensory deficit, peripheral neuropathy, central nervous system deficit, cranial nerve deficit, ataxia, generalized weakness, exertional intolerance and myofacial dysfunction. While there are a wide variety of tools available to assess functioning, they refer to different aspects of functioning: some measures for the changes in body functions [22], and the others for activity limitations and participation restrictions in life situations (e.g., patient questionnaires, clinician-based rating scales like the Performance) [20,21]. Areas of functioning and health are scarcely captured comprehensively by already existing tools. The ICF is a useful tool framework to encourage a comprehensive bio-psycho-social assessment of functioning. What makes the BCSQ-BC different is its basis within the WHO International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [13].

The BCSQ-BC is designed to assess functional outcome. In this study, there were significant correlations between its items and EORTC domains. The data gained from the cross-sectional survey are supporting the content validity of the BCSQ-breast cancer. More items in the activity and participation were significantly correlated with physical, role, emotional and social functions than items in the part of body. Functioning at the level of the whole person in a social context may be more directly related with functional domain of EORTC than at the level of body or body part. Psychological function, poor body image impaired by surgery or chemotherapy categorized as health condition were interacted with not only emotional and social function but also physical function measured by DASH. The BCSQ-BC also embraces many social functions such as labor and employment services and family or health professional relationships. These were correlated with the social functioning of the EORTC. Some environmental factors were strongly associated with emotional functioning. Interestingly, friends and individual attitudes of friends were related with physical function. Relationship with friends may be influenced either by one's physical function, or this external factor may affect some physical functioning levels. The patient's functioning is conceived as a dynamic interaction between the underlying health condition and specific personal and environmental contextual factors [11,23]. It has been demonstrated that physical function had some influence on social and psychological function which were highly related to emotional function [24]. In our study, we found the interactions between health conditions and contextual factors in the ICF framework adopting a multifactor understanding of function and disability and merging several factors into a bio-psycho-social perspective.

Lymphedema and range of motion are significantly associated with type of surgery. Previous study revealed that those having a modified radical mastectomy had less external rotation in comparison with those having a lumpectomy [25]. The prevalence of pectoralis tightness and lymphedema were significantly greater in the mastectomy group compared with the breast-conserving therapy group [15]. We also demonstrated that patients having a mastectomy had more immobility of joint and lymphatic dysfunction such as lymphedema than those having conservative surgery.

There are multiple phases that impact an individual's life throughout the course of cancer and its treatments. Possible dysfunctions during the initial phase of diagnosis and treatment are different from those that may arise from other phases, i.e., during the advanced phases of recurrence or end-of-life [14]. We identified and analyzed several common dysfunctions according to the course of cancer treatment using BCSQ-BC. Weakness and exercise intolerance is the main problems in the treatment phase, while insomnia is prevalent in the after-treatment phase. Littman et al. [26] conducted a longitudinal cohort study and found that physical activity levels decreased by 50% in the 12 months after diagnosis and overall physical activity levels had increased at 19-20 months post-diagnosis. Effective and efficient rehabilitation services specified to the various phases could be developed based on our data.

We have several limitations preventing the formulation of more definitive conclusions. First, converting the Brief ICF for breast cancer into a questionnaire posed problems. The ICF is written in scientific and medical terms and necessary to reword some domains and the scoring system into a language more easily understood. In addition, the international ICF Core Set should be translated from the original English version into Korean language. Generally, a self-administered questionnaire should not only be well-translated linguistically but also be adapted culturally to maintain the quality and validity of the content. We used the ICF manual developed by Shin et al. [27] written in Korean and we had an effort to correct some complex terms into a simple and plain one in the development phase. However, to develop an ICF-oriented assessment with an international comparability, the application of item response theory and the methodology of adaptive testing are needed. We are extending our study using Rasch model, item response model used most widely. Second, the data gained from the cross-sectional survey and most were under early phase of cancer and treatment. A long-term follow-up study is required with a large number with more advanced phase.

The BCSQ-BC developed from the ICF Core Set for breast cancer is a reliable and valid instrument to measure the functioning of breast cancer patients and could be useful for identifying the problems comprehensively in functioning of patients with breast cancer. The interactions between health conditions and contextual factors were found in the ICF framework adopting a multifactor understanding of function and disability. Environmental factors referring to interpersonal support should be included in the functional assessment for breast cancer survivors.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant of the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (08-2010-047).

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:827–841. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fialka-Moser V, Crevenna R, Korpan M, Quittan M. Cancer rehabilitation: particularly with aspects on physical impairments. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35:153–162. doi: 10.1080/16501970306129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasmuth T, von Smitten K, Kalso E. Pain and other symptoms during the first year after radical and conservative surgery for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:2024–2031. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods M, Tobin M, Mortimer P. The psychosocial morbidity of breast cancer patients with lymphoedema. Cancer Nurs. 1995;18:467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimozuma K, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Hirji K. Quality of life in the first year after breast cancer surgery: rehabilitation needs and patterns of recovery. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;56:45–57. doi: 10.1023/a:1006214830854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knobf MT. Symptoms and rehabilitation needs of patients with early stage breast cancer during primary therapy. Cancer. 1990;66(6 Suppl):1392–1401. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900915)66:14+<1392::aid-cncr2820661415>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aaronson NK, van Dam FS, Polak CE, Zittoun R. Prospects and problems in European psychosocial oncology. A survery of the EORTC Study Group on Quality of Life. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1987;4:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheville AL, Beck LA, Petersen TL, Marks RS, Gamble GL. The detection and treatment of cancer-related functional problems in an outpatient setting. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0461-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoo HJ, Ahn SH, Eremenco S, Kim H, Kim WK, Kim SB, et al. Korean translation and validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast (FACT-B) scale version 4. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:1627–1632. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-7712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stucki G, Grimby G. Applying the ICF in medicine. J Rehabil Med. 2004;(44 Suppl):5–6. doi: 10.1080/16501960410022300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cieza A, Ewert T, Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Stucki G. Development of ICF Core Sets for patients with chronic conditions. J Rehabil Med. 2004;(44 Suppl):9–11. doi: 10.1080/16501960410015353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brach M, Cieza A, Stucki G, Füssl M, Cole A, Ellerin B, et al. ICF Core Sets for breast cancer. J Rehabil Med. 2004;(44 Suppl):121–127. doi: 10.1080/16501960410016811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber LH. Cancer rehabilitation into the future. Cancer. 2001;92(4 Suppl):975–979. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4+<975::aid-cncr1409>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang EJ, Park WB, Seo KS, Kim SW, Heo CY, Lim JY. Longitudinal change of treatment-related upper limb dysfunction and its impact on late dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a prospective cohort study. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:84–91. doi: 10.1002/jso.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A The EORTC Quality of Life Group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JY, Lim JY, Oh JH, Ko YM. Cross-cultural adaptation and clinical evaluation of a Korean version of the disabilities of arm, shoulder, and hand outcome questionnaire (K-DASH) J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:570–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG) Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected] Am J Ind Med. 1996;29:602–608. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jester A, Harth A, Wind G, Germann G, Sauerbier M. Disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) questionnaire: determining functional activity profiles in patients with upper extremity disorders. J Hand Surg Br. 2005;30:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehmann JF, DeLisa JA, Warren CG, deLateur BJ, Bryant PL, Nicholson CG. Cancer rehabilitation: assessment of need, development, and evaluation of a model of care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1978;59:410–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whelan TJ, Mohide EA, Willan AR, Arnold A, Tew M, Sellick S, et al. The supportive care needs of newly diagnosed cancer patients attending a regional cancer center. Cancer. 1997;80:1518–1524. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1518::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheville AL, Troxel AB, Basford JR, Kornblith AB. Prevalence and treatment patterns of physical impairments in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2621–2629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cieza A, Stucki G. New approaches to understanding the impact of musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ringdal GI, Ringdal K, Kvinnsland S, Götestam KG. Quality of life of cancer patients with different prognoses. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:143–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00435257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hack TF, Kwan WB, Thomas-Maclean RL, Towers A, Miedema B, Tilley A, et al. Predictors of arm morbidity following breast cancer surgery. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1205–1212. doi: 10.1002/pon.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littman AJ, Tang MT, Rossing MA. Longitudinal study of recreational physical activity in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin EK, Shin HI, Kim SH, Kim WS. ICF Guideline for User. Seoul: Statistics Korea; 2011. pp. 21–75. [Google Scholar]