Abstract

Background

Few cohort studies of the health effects of urban air pollution have been published. There is evidence, most consistently in studies with individual measurement of social factors, that more deprived populations are particularly sensitive to air pollution effects.

Methods

Records from the 1996 New Zealand census were anonymously and probabilistically linked to mortality data, creating a cohort study of the New Zealand population followed up for 3 years. There were 1.06 million adults living in urban areas for which data were available on all covariates. Estimates of exposure to air pollution (measured as particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than 10 μm, PM10) were available for census area units from a previous land use regression study. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate associations between cause-specific mortality rates and average exposure to PM10 in urban areas, with control for confounding by age, sex, ethnicity, social deprivation, income, education, smoking history and ambient temperature.

Results

The odds of all-cause mortality in adults (aged 30–74 years at census) increased by 7% per 10 μg/m3 increase in average PM10 exposure (95% CI 3% to 10%) and 20% per 10 μg/m3 among Maori, but with wide CI (7% to 33%). Associations were stronger for respiratory and lung cancer deaths.

Conclusions

An association of PM10 with mortality is reported in a country with relatively low levels of air pollution. The major limitation of the study is the probable misclassification of PM10 exposure. On balance, this means the strength of association was probably underestimated. The apparently greater association among Maori might be due to different levels of co-morbidity.

Keywords: Air pollution, environmental epidemiology, mortality SI, social inequalities

Anthropogenic air pollution is thought to cause a substantial global burden of disease, even if conservative assumptions are used for the analysis.1 Most epidemiological studies of air pollution effects use a time series design, in which day-to-day changes in morbidity or mortality (usually in a single city) are related to day-to-day changes in air pollution exposure. These studies have the advantage of controlling for time invariant (or slowly varying) confounding factors by design. Time series studies provide extensive and detailed evidence of short-term air pollution effects, but are not the best basis for public health policy on air pollution.2 This is because cohort studies suggest that long-term exposures have much greater public health impact than short-term exposures. Because it is difficult to estimate air pollution exposure for large populations over long periods, relatively few cohort studies have been reported and few such studies have been conducted outside north America and Europe.3–18

We report here the findings from a longitudinal study in New Zealand, based on the national census. In New Zealand, major sources of urban air pollution are home heating and motor vehicle emissions and levels of pollution are low by international standards. Typical annual average levels of particulate air pollution (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than 10 μm, PM10) at monitoring stations in the main urban centres are in the range 15–25 μg/m3. In this study, we analyse the spatial association between average PM10 exposure and mortality over the years 1996–9. We also investigate potential modification by social factors (age, sex, ethnicity, income, education and area level deprivation).

We hypothesise a priori that effects of PM10 on mortality will be stronger for cardiorespiratory causes of death than for all diseases, because these causes are most sensitive to air pollution effects.

Methods

The New Zealand Census-Mortality Study is a population-wide cohort study, in which the cohort consists of the entire 1996 resident population (N=3 732 000) and the outcome of interest is mortality. For this analysis, records from the 1996 census were anonymously linked to 3 years of subsequent mortality data, creating a cohort study of the New Zealand population followed up for 3 years.19 20 In New Zealand, urban areas are defined as cities having a population of at least 30 000 people; about half of the approximately 2000 census areas are classified as urban. Because the definition of ‘urban areas’ in New Zealand includes small towns and suburbs, many urban census areas have low levels of air pollution.

Record linkage

The method of record linkage has been described in detail elsewhere.19 Briefly, probabilistic record linkage is a process used to link two files of records, in which records in one file have a corresponding record in the other file. Records from the first file are compared with records from the second file in order to find ‘matching’ record pairs (ie, two records belonging to the same individual). Census and mortality records were linked using date of birth (day, month and year as separate matching variables), country of birth, sex, ethnicity and address of usual residence. (Geocoded addresses were the most discriminatory matching variable.) Linkage was restricted to individuals aged 74 years or below at the time of the census. The proportion of mortality records linked overall was 78%,20 and varied by sex, age, ethnicity and the deprivation index.19 Weights were therefore applied to adjust for linkage bias, by strata of sex, age, ethnicity, deprivation, rurality and cause of death.21 For example, if 20 of 30 Maori men who died aged 45–64 years and living in moderately deprived (see below) rural areas of New Zealand were linked to a census record, each of the 20 linked records received a weight of 1.5 (30/20). The estimated proportion of links being true links was 97%.

Air pollution exposure estimation

Air pollution monitoring data are typically only available for a few sites and may not be representative of exposure in other areas. Detailed atmospheric dispersion modelling can be used to provide estimates of air pollution exposure for small areas, but these models are difficult to apply to large areas due to data and computer processing limitations. The method of air pollution exposure assessment has been described in detail elsewhere.22 Briefly, the approach to modelling long-term average PM10 was as follows. Atmospheric dispersion modelling results were available for one city (Christchurch, population 300 000). These data were assumed to be representative of the spatial pattern of annual average PM10 exposures for small areas (census area units) in Christchurch.23 Data on meteorological variables and indicators of air pollutant emissions for these areas were used as predictors of PM10 exposure in Christchurch, using regression models.

The predictors for the regression models were: census data on domestic heating; estimates of industrial emissions; and vehicle kilometres travelled within small areas. Because data for these predictor variables were available for all of New Zealand, we were able to extrapolate the empirical results for the Christchurch regression model to urban census area units throughout the country.

The resulting exposure estimates agreed well with multiyear averages of PM10 based on routine monitoring data for urban centres (1995–2001) (N=43; r2=0.87). While we acknowledge that there may be considerable exposure misclassification, we assume that the PM10 estimates are representative of long-term average spatial patterns of exposure during the 1990s.

Ideally, for analyses with the New Zealand Census Mortality Study data we would have used the continuous PM10 estimates for individual census areas. However, because the New Zealand Census Mortality Study data contain census information at unit record level, access to the data is restricted and additional data can only be added if confidentiality is not compromised as a result. Assigning continuous PM10 estimates at census area level would have permitted many census areas to be uniquely identified. In order to maintain confidentiality, it was necessary to aggregate the PM10 estimates into quintiles before they could be merged with the census data. Quintiles of exposure were calculated based on the estimates for individual census areas. For this purpose, we assigned a PM10 estimate of 0 μg/m3 to rural census areas where PM10 estimates were unavailable. The average PM10 level for all New Zealand census areas was 8.3 μg/m3 (SD 8.4 μg/m3) and the cut-off values between PM10 quintiles were 0.0, 0.5, 12.5 and 15.4 μg/m3.

Individuals were assigned to quintiles of PM10 exposure depending on their census area of residence on census night. In order to avoid bias affecting analyses in smaller rural areas due to migration to cities following the development of disease, we restricted the analyses to the urban population. This resulted in 1 065 645 observationsi with complete data. Following restriction to the urban population, the lowest two quintiles of exposure had relatively few observations (table 1). For this reason, and given the small variation in PM levels between quintiles 1 and 2, we combined the two lowest quintiles of PM10 to produce four categories in total. The estimated mean PM10 levels for these categories were 0.1, 7, 14 and 19 μg/m3 (long-term averages).

Table 1.

Summary data

| Census counts | Deaths* | ||||||||

| All | Complete data† | All causes | Natural causes‡ | Cardiovascular | Respiratory | Lung cancer | Injury | Other | |

| Age (decade) | |||||||||

| 30 | 443 610 | 347 772 | 1152 | 552 | 168 | 48 | 27 | 453 | 483 |

| 40 | 375 699 | 291 885 | 1941 | 1482 | 567 | 156 | 96 | 294 | 927 |

| 50 | 257 274 | 199 044 | 3645 | 3183 | 1155 | 474 | 309 | 186 | 1830 |

| 60 | 199 599 | 157 185 | 7794 | 7056 | 2814 | 1410 | 759 | 186 | 3387 |

| 70 | 88 275 | 69 750 | 6237 | 5664 | 2574 | 1125 | 495 | 111 | 2421 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 661 314 | 515 007 | 12 468 | 10 656 | 4881 | 1917 | 1044 | 903 | 4770 |

| Female | 703 137 | 550 635 | 8301 | 7281 | 2397 | 1296 | 639 | 327 | 4281 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Maori | 121 026 | 87 825 | 2253 | 1908 | 861 | 414 | 243 | 180 | 801 |

| Pacific | 59 574 | 35 916 | 771 | 651 | 315 | 84 | 54 | 42 | 327 |

| European | 1 183 851 | 941 904 | 17 745 | 15 378 | 6096 | 2715 | 1389 | 1011 | 7923 |

| Income (tertiles) | |||||||||

| Missing | 255 492 | ||||||||

| Lower | 375 462 | 356 853 | 11 973 | 10 476 | 4410 | 2115 | 1038 | 537 | 4908 |

| Middle | 363 870 | 350 490 | 5571 | 4779 | 1878 | 774 | 435 | 375 | 2547 |

| Upper | 369 627 | 358 302 | 3225 | 2679 | 990 | 318 | 210 | 318 | 1596 |

| NZDep (quintiles) | |||||||||

| Missing | 768 | ||||||||

| Rich | 352 656 | 289 071 | 3918 | 3387 | 1278 | 477 | 252 | 234 | 1926 |

| 278 199 | 225 192 | 3729 | 3240 | 1254 | 531 | 291 | 204 | 1740 | |

| 257 613 | 204 690 | 4014 | 3477 | 1389 | 612 | 333 | 237 | 1779 | |

| 247 107 | 189 117 | 4473 | 3867 | 1608 | 774 | 405 | 267 | 1827 | |

| Poor | 228 111 | 157 572 | 4638 | 3963 | 1746 | 819 | 402 | 288 | 1779 |

| Education | |||||||||

| Missing | 66 492 | ||||||||

| None | 443 736 | 353 280 | 10 446 | 9150 | 3789 | 1860 | 981 | 480 | 4317 |

| School | 344 745 | 286 479 | 4584 | 3915 | 1536 | 660 | 330 | 300 | 2091 |

| Higher | 509 478 | 425 883 | 5742 | 4869 | 1953 | 693 | 372 | 450 | 2646 |

| Smoking | |||||||||

| Missing | 100 926 | ||||||||

| Current | 283 992 | 232 995 | 5559 | 4713 | 1998 | 1317 | 789 | 450 | 1794 |

| Past | 328 548 | 283 470 | 7812 | 6975 | 2784 | 1425 | 690 | 300 | 3300 |

| Never | 650 991 | 549 180 | 7401 | 6246 | 2493 | 471 | 207 | 477 | 3957 |

| Temperature (°C) | |||||||||

| 0.2 | 168 261 | 137 571 | 3003 | 2625 | 1041 | 480 | 267 | 150 | 1335 |

| 2 | 224 265 | 176 730 | 3849 | 3300 | 1329 | 648 | 315 | 234 | 1638 |

| 3 | 249 363 | 199 971 | 4131 | 3576 | 1491 | 636 | 351 | 255 | 1752 |

| 5 | 354 780 | 275 739 | 5172 | 4419 | 1809 | 807 | 414 | 330 | 2223 |

| 7 | 367 788 | 275 634 | 4614 | 4014 | 1611 | 639 | 333 | 264 | 2100 |

| Particulate (μg/m3) | |||||||||

| 0.1 | 72 102 | 57 213 | 999 | 861 | 348 | 135 | 69 | 51 | 462 |

| 7 | 319 914 | 251 109 | 4665 | 3975 | 1659 | 702 | 375 | 312 | 1992 |

| 14 | 506 913 | 388 134 | 7083 | 6132 | 2472 | 1050 | 549 | 417 | 3141 |

| 19 | 465 522 | 369 189 | 8022 | 6969 | 2799 | 1323 | 693 | 444 | 3453 |

| Totals | 1 364 451 | 1 065 645 | 20 769 | 17 937 | 7278 | 3210 | 1686 | 1224 | 9048 |

Weighted counts, for deaths occurring among the census respondents with complete data.

The complete dataset is that used for final analyses in this paper.

All causes of death excluding accidents and injury.

Ethnicity and socioeconomic position are strong predictors of mortality in New Zealand, and potential confounders of the association of air pollution with mortality. We assigned each respondent to a mutually exclusive ethnic group using a prioritisation system commonly used in New Zealand: Maori, if any one of the responses was Maori; Pacific, if any one response was Pacific but not Maori; and the remainder non-Maori non-Pacific (mostly New Zealand European). Smoking status was reported in the census using the categories: never smoker, ex-smoker, or current smoker.24 Socioeconomic position was characterised as: total household income, with adjustment for the number of children and adults in the household to allow for economies of scale, log-transformed having first set all values of less than NZ$1000 to equal NZ$1000;20 highest educational qualification (higher than school, school, or none); and neighbourhood deprivation measured by the NZDep index (in quintiles).25 This index of deprivation within small geographical areas was calculated using census data on socioeconomic characteristics (eg, car access, tenure and receipt of benefits) at aggregations of approximately 100 people, and assigned to mortality data by use of address.

As climate is correlated with PM10, and associated with mortality (independently of PM10), temperature has the potential to confound air pollution effects. Therefore, we also included estimates of long-term average minimum temperature (in addition to the above sociodemographic factors) in the models, also in quintiles based on place of residence. These data were derived from an interpolated temperature surface.26 Mean values for the minimum temperature quintiles were 0.2, 2, 4, 5 and 7°C.

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate associations between all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates and average exposure to PM10, with control for confounding by age, sex, ethnicity, social deprivation, income, education, smoking history and average minimum temperature. As death is a rare outcome over 3 years for the age groups included in the analysis, logistic regression results differ very little from those from either Poisson or Cox proportional hazards modelling. Initial models incorporated PM10 categories as dummy variables, and given a reasonably linear dose–response, final models used the estimated mean PM10 for these four categories (see above). In order to facilitate comparison with overseas findings, we report results for adults aged 30–74 years. In final models, age was included as a linear plus a squared term, and the income variable was natural-log transformed. All other covariates were included as dummy variables (table 2).

Table 2.

Logistic regression model including all variables listed as independent variables (all deaths, all ethnicities: N= 1 065 645)*

| OR | 95% CI | ||

| lower | upper | ||

| Particulate | |||

| PM10 (μg/m3) | 1.007 | 1.003 | 1.010 |

| Temperature quintile (base: lowest) | |||

| 2 | 0.967 | 0.915 | 1.022 |

| 3 | 0.987 | 0.932 | 1.046 |

| 4 | 0.957 | 0.908 | 1.010 |

| 5 | 0.908 | 0.861 | 0.959 |

| Age | 1.088 | 1.071 | 1.105 |

| Age squared | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Natural log of income | 0.819 | 0.799 | 0.839 |

| Sex (base: male) | |||

| Female | 0.598 | 0.579 | 0.618 |

| Ethnicity (base: Māori) | |||

| Pacific | 0.813 | 0.731 | 0.905 |

| European | 0.500 | 0.472 | 0.529 |

| Deprivation quintile (base: least deprived) | |||

| 2 | 1.078 | 1.025 | 1.134 |

| 3 | 1.173 | 1.116 | 1.234 |

| 4 | 1.330 | 1.265 | 1.399 |

| 5 | 1.548 | 1.469 | 1.632 |

| Smoking (base: current smoker) | |||

| past | 0.706 | 0.677 | 0.736 |

| never | 0.498 | 0.477 | 0.519 |

| Education (base: none) | |||

| school | 0.933 | 0.895 | 0.971 |

| higher | 0.860 | 0.828 | 0.894 |

Rounded; for logit form of model, constant −6.528 (−7.036 to −6.020).

Any association of air pollution with mortality might be modified by social and environmental factors, due to different vulnerability or intensity of exposure to air pollution. We tested for interaction both by stratification and by inclusion of interaction terms.

Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by restricting the dataset for analysis to those people who had lived in the same geographical unit at the 1991 census as they did at the time of exposure assignment (1996) in this cohort study. This restriction should reduce exposure misclassification by excluding those people who have not been exposed to the same level of PM10 for at least 5 years.

Results

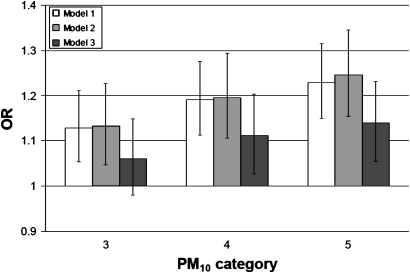

When PM10 was modelled using dummy variables, there was an approximately linear increase in mortality with increasing average PM10 exposure (figure 1). Three models are shown: (1) adjusting for sex, age and ethnicity on all observations (N=1 364 454); (2) the same model, but restricted to observations with non-missing data on other covariates (N=1 065 645; a test of any selection bias compared with model 1); (3) fully adjusted model (N=1 065 645; a test of possible confounding compared with model 2). There is no meaningful difference between models 1 and 2, suggesting no selection bias when restricting analyses to those with full data on covariates. Adjusting for potential confounders in model 3 attenuated the OR for all non-referent groups, although the relative differences between quintiles 3, 4 and 5 were not much reduced. That is, adjusting for confounders mostly closed the gap between the referent group and quintile 3.

Figure 1.

OR and 95% CI of all-cause mortality for people living in the three non-referent PM10 categories, compared with quintiles 1 and 2 combined. Model is for sexes combined, restricted to adults aged 30–74 years on census night, urban population, with covariates as follows: model 1: age, sex, ethnicity, all data, N=1 364 454; model 2: age, sex, ethnicity, data with non-missing values for covariates in model 3, N=1 065 645; model 3: age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, income, education, smoking, temperature, N=1 065 645.

Considering the preferred model 3, the OR increased monotonically and linearly with increasing PM10 level, and the 95% CI for the two highest quintiles excluded 1.0. Given the approximately linear association of PM10 with mortality described above, subsequent models incorporated PM10 as a linear term, using the average PM10 for each category) (tables 2 and 3). Table 2 shows the same model as in figure 1, except for the continuous treatment of PM10. The OR of 1.007 corresponds to a 1 unit increase in PM10, which equates to an increase of 7% (95% CI 3% to 10%) in the odds of all-cause mortality in adults (aged between age 30 and 74 years at census) per 10 μg/m3 increase in long-term average PM10 exposure.

Table 3.

Findings by subgroups of ethnicity and cause of death (model 3, fully adjusted)

| N* | OR (per 1 μg/m3 PM10) | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Model | ||||

| All deaths, all ethnicities | 1 065 645 | 1.007 | 1.003 | 1.010 |

| All deaths, living in the same census area as for the 1991 census | 601 401 | 1.008 | 1.004 | 1.011 |

| All natural causes, all ethnicities (excludes accidents and injury) | 1 063 563 | 1.007 | 1.003 | 1.010 |

| All natural causes, European | 940 107 | 1.006 | 1.003 | 1.010 |

| All natural causes, Maori | 87 615 | 1.018 | 1.007 | 1.029 |

| Analyses by specific cause of death, based on ICD9 codes† | ||||

| Lung cancers (ICD 162) | 1 050 222 | 1.015 | 1.004 | 1.026 |

| Respiratory disease (ICD 162, 470–478, 490–519) | 1 051 464 | 1.013 | 1.005 | 1.021 |

| Cardiovascular disease (ICD 393–438) | 1 054 731 | 1.006 | 1.001 | 1.011 |

| Accidents and injury (ICD 800–949) | 1 049 646 | 1.004 | 0.990 | 1.018 |

| Other, includes unspecified‡ | 1 056 288 | 1.005 | 1.001 | 1.010 |

Rounded.

Note: Models included persons dying from the specified causes (coded 1) and people presumed alive at the end of follow-up (coded 0), but excluded persons dying from other causes. Respiratory disease includes lung cancers.

‘Other’ deaths are all those deaths (including unspecified) that are not included among lung cancer, respiratory, cardiovascular disease or accidents.

ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

We found stronger effects of PM10 among people who lived in the same census area in 1991 (at the time of the previous census), 8% (4% to 12%) per 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10. By cause of death, the association was similar for all natural causes, 7% (3% to 10%), but substantially stronger for respiratory deaths (including lung cancers), 14% (5% to 23%) and for lung cancers, 16% (4% to 29%). For cardiovascular disease, 6% (1% to 12%) and for ‘other and unspecified’ causes of death, 5% (1% to 10%), the association was marginally significant; while for accidental deaths and injuries, the association was non-significant, 4% (−9% to 20%) (table 3).

Considering interaction with social variables, there was an apparently stronger association of PM10 with all-cause mortality among Maori, 20% (7% to 33%). However, the 95% CI for Europeans overlapped that for Maori, 7% (3% to 10%). A Wald test for interaction between ethnicity and PM10 was not significant (p=0.12). There were no statistically significant interactions with age, sex, income, deprivation, educational status or average temperature. Mortality was lower among people living in warmer census areas, and the difference between the lowest and the highest quintile of annual average temperature was statistically significant.

Discussion

Using linked mortality and census data, we report a significant positive association between estimated long-term exposure to air pollution (PM10) and mortality in New Zealand urban areas. This setting includes approximately 75% of the New Zealand population, who are exposed to relatively low levels of PM10 compared with other countries.

Selection bias and confounding seem unlikely to explain our results. There is no evidence of selection bias (figure 1). The results persist after controlling for plausible confounders, including multiple measures of socioeconomic position and smoking. It seems unlikely that mismeasured or unknown confounders might explain the remaining association.

There is likely to be substantial misclassification of the air pollution exposure. Most of this misclassification was probably non-differential by mortality risk (meaning we have probably significantly underestimated the true strength of association). There is potential differential misclassification of PM10 by mortality risk in our study, because our assessment was based on modelling in one city using proxies, including domestic heating, estimates of industrial emissions and vehicle kilometres travelled within small areas. If these proxies are not such reliable predictors of PM10 in other cities, and are (say) correlated with socioeconomic position, then it may be that our PM10 estimates are also capturing aspects of socioeconomic exposure. However, the fact that an association remained after extensive control of socioeconomic factors, including individual level income and education, makes this an unlikely explanation of the results. The use of modelled estimates of PM10 exposure will tend to smooth the data and reduce the resulting CI. However, this should not affect the central effect estimates.

It is possible that less healthy people might migrate towards health services (or other service amenities) that happen to be in more polluted areas—a form of reverse causation or endogeneity. However, we think this is unlikely to be an important factor as New Zealand cities are relatively small (maximum 1.4 million), and most suburbs in New Zealand's main cities have relatively good access to hospitals.

The odds of all-cause mortality in adults (aged between 30 and 74 years at census) increased by 7% (95% CI 3% to 10%) per 10 μg/m3 increase in average PM10 exposure. Our observations are consistent with an increasing number of studies of long-term exposure to particulate matter and mortality.3–10 13–18

The original US Six Cities Study reported an adjusted mortality rate ratio of 1.27 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.48) for the most polluted compared with the least polluted city, corresponding to 18.2 and 46.5 μg/m3 PM10, respectively3—equivalent to an increase in mortality of approximately 10% per 10 μg/m3 PM10. In the US Nurses Health Study, there was a 16% (5% to 28%) increase in all-cause mortality per 10 μg/m3 PM10.14 It is not yet clear to what extent the heterogeneity in reported dose response in those studies is related to differences in the accuracy of exposure measurement, to differences in the toxicity of complex mixtures of pollutants at differing levels of exposure, and/or differences in the sensitivity of exposed populations.

The exposure measures in other studies are not directly comparable. Recent studies use the more specific measure PM2.5 (particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 μm) rather than PM10, whereas several European studies use black smoke or total suspended particulates as the exposure measure. The association between particulate air pollution exposure and mortality is usually found to be strongest for finer fractions, such that the dose response for PM2.5 is greater than for PM10, which in turn is greater than for total suspended particulates. An extended follow-up of the US Six Cities Study reported a 14% (6% to 22%) increase in mortality per 10 μg/m3 PM2.5,9 whereas the American Cancer Society Study reported 6% (2% to 11%) and the Nurses Health Study 26% (2% to 54%), while coarse particulate matter exposure (PM10–2.5) was not associated with an increase in mortality in that study.27 An analysis based on electoral wards in the UK found a 1.3% (1% to 1.6%) increase in all-cause mortality per 10 μg/m3 increase in black smoke.10 In 18 regions in France, the PAARC study reported a 7% (3% to 10%) increase per 10 μg/m3 increase in black smoke and a 5% (2% to 8%) increase for total suspended particulates.7 In The Netherlands, there was a 5% (0% to 10%) increase in mortality per 10 μg/m3 increase in black smoke.

Our study assessed the association of PM10 and mortality over 3 years. In the US Nurses Health Study, mortality was most strongly associated with average PM10 exposures in the 24 months before death. In the UK, the association, although weak, was stronger for exposure in the 4 years before death. However, a re-analysis of the American Cancer Society Study found no clear effect of exposure period.17

A priori, we hypothesised that the association of PM10 with mortality in our study would be stronger for a cohort restricted to those census respondents who lived in the same census area at the time of the 1991 census. We also hypothesised that the association of PM10 with mortality would be stronger for cardiorespiratory deaths. Our results were consistent with these a priori hypotheses, strengthening the ability to make causal inference.

There is some evidence, most consistently in studies with individual measurements of social factors, that more deprived populations are particularly sensitive to air pollution effects.5 11 12 28 29 Our ability to detect a true difference by ethnicity in sensitivity to air pollution was limited by the relatively small Maori population. Although not significant, the difference in our central effect estimates for European and Maori was substantial: 7% versus 20%. The reasons for this difference, if real, are not clear. This might reflect a higher prevalence of pre-existing cardiorespiratory disease among Maori, or a difference in the toxicity of air pollution to which different ethnic groups are typically exposed. Alternatively, this finding may reflect biases in exposure estimates. We found no other suggestion of interaction of social factors with PM10 in the association with mortality.

Conclusion

In this longitudinal study we report an association of PM10 with mortality, consistent with that reported elsewhere, in a country with low levels of air pollution. The major limitation of our study is the probable misclassification of the PM10 exposure. On balance, this means we have probably underestimated the strength of association. The study design has several strengths, including national population coverage and good control of confounding. We found that the association was, as hypothesised a priori, stronger for cardiorespiratory deaths and people with less residential mobility.

What is already known on this subject.

Relatively few cohort studies of the health effects of urban air pollution have been published, particularly outside north America and Europe. We report here findings from a longitudinal study in New Zealand, based on the national census. There is evidence, most consistently in studies with individual measurement of social factors, that more deprived populations are particularly sensitive to air pollution effects.

What this study adds.

We found an association of PM10 with mortality in a country with relatively low levels of air pollution. There was some evidence that Maori may have greater susceptibility to life-shortening effects of air pollution. This might reflect a higher prevalence of pre-existing cardiorespiratory disease among Maori.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank June Atkinson for preparing the data for analysis.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was funded by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA). The New Zealand Census Mortality Study is conducted in collaboration with Statistics New Zealand and within the confines of the Statistics Act 1975. The New Zealand Census Mortality Study study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand, and receives continuing funding from the Ministry of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Contributors: TB conceived the analysis and contributed to the design, interpretation and revision of drafts. SH performed the analyses, drafted the text of the paper and contributed to the design and interpretation of results. SH had full access to the data, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the analysis and the accuracy of the results. AW contributed to study design, the interpretation of results and revision of drafts.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

i: All counts were randomly rounded to a multiple of 3 in order to preserve confidentiality, as per Statistics New Zealand protocol. For this reason, subtotals may not match across categories. Note that regression analyses, however, were undertaken on actual unit record data.

References

- 1.Cohen AJ, Anderson HR, Ostro B, et al. The global burden of disease due to outdoor air pollution. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2005;68:1301–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMichael AJ, Anderson HR, Brunekreef B, et al. Inappropriate use of daily mortality analyses to estimate longer-term mortality effects of air pollution. Int J Epidemiol 1998;27:450–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dockery DW, Pope CA, Xu X, et al. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1753–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope CA, Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, et al. Particulate air pollution as a predictor of mortality in a prospective study of U.S. adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;151:669–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krewski D, Burnett R, Goldberg M. Reanalysis of the Harvard six cities study and the American cancer society study of particulate air pollution and mortality. Cambridge, MA: Health Effects Institute, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope CA, Burnett RT, Thun MJ, et al. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution. JAMA 2002;287:1132–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filleul L, Rondeau V, Vandentorren S, et al. Twenty five year mortality and air pollution: results from the French PAARC survey. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:453–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gehring U, Heinrich J, Krämer U, et al. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and cardiopulmonary mortality in women. Epidemiology 2006;17:545–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laden F, Schwartz J, Speizer FE, et al. Reduction in fine particulate air pollution and mortality: extended follow-up of the Harvard Six Cities study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:667–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott P, Shaddick G, Wakefield JC, et al. Long-term associations of outdoor air pollution with mortality in Great Britain. Thorax 2007;62:1088–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laurent O, Bard D, Filleul L, et al. Effect of socioeconomic status on the relationship between atmospheric pollution and mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:665–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naess O, Piro FN, Nafstad P, et al. Air pollution, social deprivation, and mortality a multilevel cohort study. Epidemiology 2007;18:686–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beelen R, Hoek G, van Den Brandt PA, et al. Long-term effects of traffic-related air pollution on mortality in a Dutch cohort (NLCS–AIR study). Environ Health Perspect 2008;116:196–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puett RC, Schwartz J, Hart JE, et al. Chronic particulate exposure, mortality, and coronary heart disease in the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;168:1161–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeger SL, Dominici F, McDermott A, et al. Mortality in the medicare population and chronic exposure to fine particulate air pollution in urban centers (2000–2005). Environ Health Perspect 2008;116:1614–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jerrett M, Finkelstein MM, Brook JR, et al. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution and mortality in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:772–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krewski D, Jerrett M, Burnett R, et al. Extended follow-up and spatial analysis of the American Cancer Society study linking particulate air pollution and mortality. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yorifuji T, Kashima S, Tsuda T, et al. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and mortality in Shizuoka, Japan. Occup Environ Med 2010;67:111–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blakely T, Salmond C, Woodward A. Anonymous linkage of New Zealand mortality and census data. Aust NZ J Public Health 2000;24:92–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill S, Atkinson J, Blakely T. Anonymous record linkage of census and mortality records: 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996 census cohorts. Wellington: University of Otago, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fawcett J, Blakely T, Atkinson J. Weighting the 81, 86, 91 & 96 census-mortality cohorts to adjust for linkage bias. Wellington: University of Otago, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingham S, Fisher G, Hales S, et al. An empirical model for estimating census unit population exposure in areas lacking quality monitoring. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2007;18:200–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zawar-Reza P, Kingham S, Pearce J. Evaluation of a year-long dispersion modelling of PM10 using the mesoscale model TAPM for Christchurch, New Zealand. Sci Total Environ 2005;349:249–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blakely T, Fawcett J, Hunt D, et al. What is the contribution of smoking and socioeconomic position to ethnic inequalities in mortality in New Zealand? Lancet 2006;368:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salmond C, Crampton P. NZDep96: what does it measure? Soc Policy J NZ 2001;17:82–100 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leathwick J, Wilson G, Stephens R. Climate surfaces for New Zealand. Hamilton: Landcare, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puett RC, Hart JE, Yanosky JD, et al. Chronic fine and coarse particulate exposure, mortality, and coronary heart disease in the Nurses' Health Study. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:1697–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deguen S, Zmirou-Navier D. Social inequalities resulting from health risks related to ambient air quality—a European review. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:27–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelucchi C, Negri E, Gallus S, et al. Long-term particulate matter exposure and mortality: a review of European epidemiological studies. BMC Public Health 2009;9:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]