Abstract

In order to identify immunodominant antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that may be used in the serodiagnosis of active tuberculosis (TB), we designed an M. tuberculosis fusion protein consisting of CFP-10 (10-kDa culture filtrate protein), ESAT-6 (6-kDa early secreted antigenic target), and the extracellular domain fragment of PPE68 (PPE68′). Then, the coding sequences of the three proteins were inserted into a prokaryotic expression vector, pET-32a(+). To enhance the immunological response, the proteins were linked together. The fusion proteins with a 6×His tag were successfully overexpressed in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified. The purified proteins were applied for detection of the total IgG titer by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with human sera from well-characterized TB cases and the control cases, and results were compared to those with purified protein derivative tuberculin (PPD). The ELISA results showed that among 140 cases of confirmed active TB and 70 control cases, CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ had a sensitivity of 73.3% and specificity of 94.3%, compared to a sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 74.3% for PPD and a sensitivity of 65% and specificity of 91.4% for CFP-10–ESAT-6. In addition, the fusion protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ stimulated a higher level of antigen-specific gamma interferon (IFN-γ) release for active-TB patients than PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6. After immunization of C57BL/6 mice, the findings indicated that the total IgG titers and the concentrations of IFN-γ in mice immunized by CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were high and induced strong, long-term humoral immunity compared to results with PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6. Thus, our study indicates that the fusion protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ may be useful as an immunodominant antigen for the serodiagnosis of active TB.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by bacteria of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, is a chronic infectious disease. Although a curable disease, it continues to be one of the most important infectious causes of death worldwide (29, 32). According to the World Health Organization's 2009 world TB reports, about one-third of the world's population is infected with M. tuberculosis and approximately 9 million people are infected with this pathogen every year, which leads to 1.8 million deaths (35). In China, it is estimated that there are 550 million people infected with M. tuberculosis, 4.5 million patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, and 2 million patients with smear-positive or culture-positive pulmonary TB. For the purpose of effective control of TB, it is of great importance to identify infected individuals. Current tests used for TB diagnosis include culturing of bacteria from body fluids and smear testing of sputum for the presence of acid-fast bacilli (AFB). The immunological tests for tuberculosis include a tuberculin skin test (TST) and T cell stimulation assays with cells of patients using mycobacterial proteins and peptides. The traditionally used TST is nonspecific because of cross-reaction to antigens both in Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine strains and in environmental mycobacteria (18). The culture technique has an advantage in distinguishing the morphology of M. tuberculosis from those of some nontuberculous mycobacteria. However, it takes a minimum of 3 to 4 weeks to get the results (34). Advanced molecular techniques, such as PCR, are costly and not available everywhere, although they have the advantages of rapidness, sensitivity, and specificity (24). Thus, more-simple and -convenient detection of M. tuberculosis becomes increasingly important in the control of TB.

Elimination of TB largely depends upon definitive early, rapid diagnosis and treatment. There are several new diagnostic techniques, such as nucleic acid amplification and immune reactions based on the cell-mediated immune response (10). Detection of antibodies using serodiagnostic tests is a rapid, easy-to-perform, user-friendly method which does not require a living cell. With the development of molecular techniques, numerous antigens for the serodiagnosis of TB have been identified and applied to obtain the ideal sensitivity and specificity in the form of individual antigen or in recombinant antigens. Previous studies indicated there were many protective antigens of M. tuberculosis, such as the 6-kDa early secretory antigenic target (ESAT-6) (2), Ag85B (17), MPT64 (12), PPE68 (22), and culture-filtered protein 10 (CFP-10) (5), isolated from short-term culture filtrate. Among these antigens, CFP-10 and ESAT-6 have been demonstrated to have the strong antigenicity for T cells and to elicit powerful immune responses and protection against M. tuberculosis, being encoded in the genomic region of difference 1 (RD-1), which is present in all the virulent members of the M. tuberculosis complex but is absent in BCG vaccine strains and is closely related to virulence of M. tuberculosis (15). The role of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 in the early diagnosis of latent TB was previously reported, and they were both vaccine candidates and diagnostic tools. The PPE68 protein is a member of the PPE protein family and is encoded by Rv3873 in the RD-1 region. Previous study indicated that PPE68 was located in the membrane and cell wall of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (4), and it has been verified to stimulate a strong specific cellular immune response and to promote the release of a high level of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) in patients infected by M. tuberculosis, suggesting that the antigen may provide an advantage in immune protection against tuberculosis infection (25).

In this study, we designed a fusion protein, CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′, from M. tuberculosis for the serodiagnosis of active TB. In order to get an insight into the fusion protein and prepare enough evidence for the succeeding diagnostic research, cloning and expression of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ are required. In the present study, we successfully expressed the fusion protein in Escherichia coli BL21 and purified it by using a HisTrap HP affinity column. We evaluated the diagnostic potential of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using sera from patients with active TB and from control subjects. Our data suggest that CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ had better sensitivity (73.3%) and specificity (94.3%) than purified protein derivative tuberculin (PPD) and CFP-10–ESAT-6. The fusion protein also stimulated a high level of antigen-specific IFN-γ release in active-TB patients. Then, after immunization of C57BL/6 mice, the data indicated that immunization with CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ induced long-term humoral immunity compared to results for PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6. In conclusion, CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ may be an efficacious immunodominant antigen for the serodiagnosis of active TB and a potential candidate for an anti-tuberculosis subunit vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture media.

The Escherichia coli DH5α and BL21(DE3) strains (Takara, Dalian, China) were used for cloning and overexpression, respectively. Both bacteria were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. When required, ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The genomic DNA of M. tuberculosis H37Rv was provided by Sichuan Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Purified protein derivative tuberculin (PPD) was purchased from Chengdu Infectious Disease Hospital, Sichuan, China.

Serum samples.

The serum samples (n = 210) were collected from the Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital and Xindu People's Hospital, Chengdu, Sichuan, China, from December 2010 through September 2011. Ethical approval for the study was granted by both the Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital and Xindu People's Hospital Ethics Committees. Then, the serum samples were divided into two groups: (i) the TB group, contained 140 patients (confirmed active-TB patients) smear positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), culture positive, PPD skin test positive, and TB lesion on chest X-ray or computed tomography (CT) positive, and (ii) the control group, which contained 30 pulmonary infection patients and 40 people determined to be healthy by physical examination who had no disease involvement or history of contact with TB. All the patients and controls included in our study were over 18 under 50 years of age. Details of patients and controls selected in the study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of two groups of TB patients and control subjects

| Study subjects (na) | No. in gender group |

Age (yr)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Tuberculosis (140) | 84 | 56 | 33.6 ± 13.2 |

| Controls | |||

| Healthy controls (40) | 25 | 15 | 25.9 ± 6.7 |

| Pulmonary infection cases (30) | 14 | 16 | 32.3 ± 12.8 |

n, no. of subjects.

Mean ± SD.

Construction of recombinant plasmids.

The antigenicity prediction of PPE68 protein sequences was first achieved using both the DNAStar software program and the HMMMTOP method (http://www.expasy.org/tools/). A 348-bp fragment (PPE68′) in the extracellular domain of PPE68 was chosen. With M. tuberculosis H37Rv, genes coding CFP-10 (Rv3874), ESAT-6 (Rv3875), and PPE68′ (Rv3873) were individually amplified with the primers listed in Table 2. In order to enhance the immunological response, the three genes were fused with a linker (described in Table 2) during the amplification steps. The PCR products were first digested with restrictive enzymes (listed in Table 2) and then cloned into the corresponding sites of the prokaryotic expression vector pET32a(+) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), resulting in recombinant plasmids, named pETcfp10, pETesat6, pETppe68′, pETcfp10-esat6, and pETcfp10-esat6-ppe68′. The identities of the recombinant plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing and enzyme digestion. Next, the plasmids were transformed into competent Escherichia coli DH5α. Then, these constructed plasmids were transformed using electroporation into competent E. coli BL21 cells, which were then selected on ampicillin (100 μg/ml) LB agar. The E.Z.N.A. plasmid minikit I (Promega) was used for plasmid purification. The E.Z.N.A. gel extraction kit (Promega) was used for DNA fragment isolation. All restriction enzymes used in this study were purchased from Fermentas.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Gene(s) | Primer, sequencea | Product size (bp) | Restriction enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| cfp10 | P1, GC GATATC ATG GCAGAGATGAAG | 303 | EcoRV, BamHI |

| P2, CG GGATCC TTA GAAGCCCATTTG | |||

| esat6 | P3, CG GGATCC ATG ACAGAGCAGCAG | 288 | BamHI, EcoRI |

| P4, CCG GAATTC TTA TGCGAACATCCCGA | |||

| ppe68′ | P5, CCG GAATTC ATG CTGTGGCACGCA | 348 | EcoRI, HindIII |

| P6, CCC AAGCTT TTA GGTGATGTGGTTGG | |||

| cfp10-esat6 | P7, GC GATATC ATG GCAGAGATGAAG | 693 | EcoRV, EcoRI |

| P8, CG GGATCC GGTGGCGGTGGCTCC GAAGCCCATTTG | |||

| P9, CG GGATCCGGTGGCGGTGGCTCCGGCGGTGGTGGATCTTAGAGCAGCAG | |||

| P10, CCG GAA TTC GGTGGCGGTGGCTCCTGCGAACATCCCGA | |||

| cfp10-esat6-ppe68′ | P11, CCGGAATTCGGTGGCGGTGGCTCCCTGTGGCACGCA | 1,041 | EcoRV, HindIII |

| P12, CCC AAGCTT TTA GGTGATGTGGTTGG |

Restriction enzymes used in this study are underlined.

Overexpression, purification, and Western blot analysis of the fusion proteins.

The Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) strain, harboring the plasmids pETcfp10-esat6 and pETcfp10-esat6-ppe68′, was cultured overnight. Overnight cultures were inoculated into fresh LB medium containing ampicillin and incubated at 37°C with shaking until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) nm reached 0.6. Then, they were induced by 1 mM isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at the mid-exponential phase of growth. Bacterial pellets were collected by centrifugation, prepared in sample buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis. Proteins were stained with a Coomassie blue dye.

The fusion proteins were purified by using a HisTrap HP affinity column with Ni2+ ions according to the manufacturer's protocol (GE Healthcare). The concentrations of the purified fusion proteins were determined by using the Enhanced BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, China).To verify the specificities of the purified fusion proteins CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′, the protein samples were first separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using Mini Protean II equipment (Bio-Rad, Life Science Research Products, California). Rabbit polyclonal anti-M. tuberculosis antiserum (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA) was used as the primary antibody. A horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was used as the secondary antibody according to the manufacturer's instructions with tissue diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining.

Indirect ELISA.

Antibody levels were evaluated in the cell-free supernatants by a standard indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described. Titers for the total immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels were determined with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a dilution of 1:4,000. The 96-well ELISA plates (Costar) were coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μl of a 30-μg/ml concentration of PPD, 100 μl of a 15-μg/ml concentration of CFP-10–ESAT-6, and 100 μl of a 10-μg/ml concentration of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′, respectively. The most suitable coating density of these proteins was determined in preliminary work. Plates were washed three times with PBST buffer (0.05% Tween 20 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]). The plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS (100 μl/well) overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBST three times, sera were diluted 1:80 in assay diluent (1% BSA in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20) and added to each well (100 μl/well), followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C. Plates were again washed with PBST buffer and further incubated with 100 μl of HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (1:4,000) for 1 h at 37°C. After the plates were washed with PBST buffer, the wells were reacted with 100 μl of citrate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.04% (wt/vol) of o-phenylenediamine and 0.02% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of 2 M H2SO4 to each well, and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a Thermo Labsystems apparatus. All the experiments were carried out at least two times.

Immunogenicities of the fusion proteins.

A whole-blood IFN-γ assay (WBIA) based on the fusion proteins CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ and PPD was performed as previously described. All wells in the microplate were filled with 200 μl of sterile culture medium (RPMI-1640) and incubated for approximately 30 min at room temperature. Heparinized whole-blood samples from 60 randomly selected cases of confirmed active-TB patients (1 ml [each case]) were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated with 100 μl PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, or CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ for 24 h at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. After stimulation, 200 μl of plasma was then taken from each well. The concentrations of IFN-γ in collected samples were determined by using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Shanghai, China). The sensitivity for the ELISA is 4 pg/ml.

Immunization of mice.

Specific-pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice (female, 6 to 8 weeks old) were provided by the Animal Center of West China Medicine Center, Sichuan University (Chengdu, China). Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Chinese Council on Animal Care and approved by West China Medicine Center Committees on Animal Experimentation. All mice were housed in groups of 5 or 6 in plastic mouse cages in a laminar-flow housing cabinet with an automatically controlled temperature of 22°C and 12 h of light. The mice were randomly divided into four groups (10 mice in each group): nonvaccinated control, PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′. PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ (10 μg protein in 0.5 ml saline/mouse) were injected in the quadriceps muscle of each hind leg, and immunization was repeated thrice at 2-week intervals. The control animals received an equal volume of saline only.

Mouse serum samples were obtained by eye bleeding at 1 weeks, 3 weeks, 5 weeks, and 7 weeks after enhanced immunization and analyzed by indirect ELISA for the presence of specific antibodies. Titers for the total IgG levels were determined with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a dilution of 1:2,000. Animal experiments were performed twice, and representative results are provided.

IFN-γ production in mice.

Mouse serum samples in each group were obtained at 1 weeks, 3 weeks, 5 weeks, and 7 weeks after enhanced immunization and analyzed individually. IFN-γ was measured by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Shenzhen, China). Blank wells (blank control wells without sample and enzyme reagent, the same as in the rest of the step), standard wells, and the sample wells were located in microtiter plates. First, standard liquid (50 μl) was added in the standard wells, and then the serum samples (50 μl) were added (samples were diluted 5-fold). Enzyme reagent (50 μl for each well) was added, except for the blank wells, gently mixed, and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. After washing with washing solution five times, color reagent A (50 μl) was added to each well, and then color reagent B (50 μl) was added and reacted for 15 min at 37°C in the dark. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl of stop solution to each well, and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a Thermo Labsystems apparatus. The concentrations of standard liquid were 0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 ng/ml.

Statistical analysis.

The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations with ranges. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed using the software program Stata-7 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) to determine the cutoff, sensitivity, and specificity. The differences in IFN-γ response levels were analyzed using Mann-Whitney tests. The statistical significance of the differences was determined by using a t test. The differences were considered to be statistically significant when a P value was less than 0.05.

RESULTS

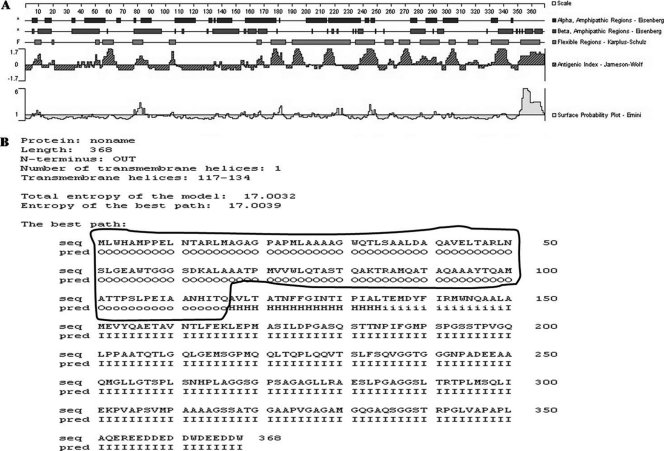

Antibody epitope of the PPE68 protein, optimized by DNAStar software and the HMMMTOP method.

The region used to construct the recombinant protein was selected by the results of the extracellular domain, the antigenic index, the flexible regions, and the hydrophilicity regions. The gene encoding the PPE68 protein (Rv3873) was 1,104 bp in length. The extracellular domain of PPE68 (PPE68′) was analyzed by both DNAStar software and HMMMTOP method (Fig. 1). The results indicated that the extracellular domain of PPE68 was base pairs 1 to 348 (circled in Fig. 1B). The optimized sequence of PPE68 is as follows: ATGCTGTGGCACGCAATGCCACCGGAGCTAAATACCGCACGGCTGATGGCCGGCGCGGGTCCGGCTCCAATGCTTGCGGCGGCCGCGGGATGGCAGACGCTTTCGGCGGCTCTGGACGCTCAGGCCGTCGAGTTGACCGCGCGCCTGAACTCTCTGGGAGAAGCCTGGACTGGAGGTGGCAGCGACAAGGCGCTTGCGGCTGCAACGCCGATGGTGGTCTGGCTACAAACCGCGTCAACACAGGCCAAGACCCGTGCGATGCAGGCGACGGCGCAAGCCGCGGCATACACCCAGGCCATGGCCACGACGCCGTCGCTGCCGGAGATCGCCGCCAACCACATCACCCAG.

Fig 1.

Epitope analysis of the PPE68 protein, using the DNAstar software program (A) or the HMMMTOP method (B). The extracellular domain of PPE68 was base pairs 1 to 348 bp (circled), analyzed by both DNAStar software and the HMMMTOP method.

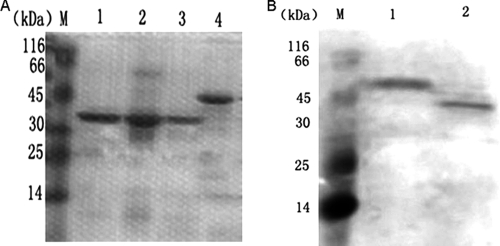

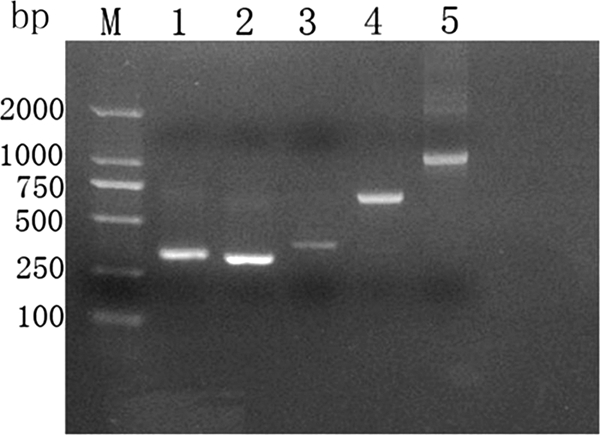

Overexpression, purification, and Western blot analysis of the fusion proteins.

As shown in Fig. 2, the candidate genes cfp10, esat6, ppe68′, cfp10-esat6, and cfp10-esat6-ppe68′ were amplified by PCR and cloned into the pET32a(+) vector. Following isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction, CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were expressed and corresponded to their predicted molecular masses of 37 kDa (CFP-10–ESAT-6) and 49 kDa (CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′) on an SDS-PAGE gel. The fusion proteins were purified by using a HisTrap HP affinity column (Fig. 3A). Western blotting showed that the purified fusion proteins CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were recognized by rabbit serum polyclonal antibody to M. tuberculosis (Fig. 3B).

Fig 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis for PCR products. Lane M, DNA marker (DL2000); lane 1, PCR product of cfp10 (303 bp); lane 2, PCR product of esat6 (288 bp); lane 3, PCR product of ppe68′ (348 bp); lane 4, PCR product of cfp10-esat6 (693 bp); lane 5, PCR product of cfp10-esat6-ppe68′ (1,041 bp).

Fig 3.

SDS-PAGE (A) or Western blot (B) analysis of the purified proteins CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′. (A) Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, CFP-10–ESAT-6 eluted by 300 mM imidazole elution buffer (37 kDa); lane 2, CFP-10–ESAT-6 eluted by 400 mM imidazole elution buffer; lane 3, CFP-10–ESAT-6 eluted by 500 mM imidazole elution buffer; lane 4, CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ eluted by 300 mM imidazole elution buffer (49 kDa). (B) Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, the purified protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ (49 kDa); lane 2, the purified protein CFP-10–ESAT-6 (37 kDa); 30 mM imidazole in binding and washing buffers and 300 mM imidazole in elution buffer were the optimal choice in our study. The fusion proteins CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were recognized by the rabbit serum polyclonal antibody of M. tuberculosis.

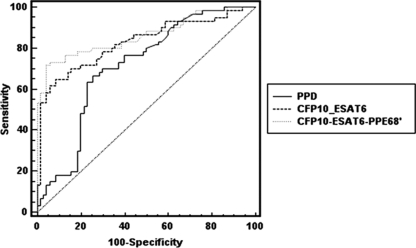

Antibody responses of two groups of TB patients and controls to the various antigens.

In our study, we identified the serodiagnostic potential of PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ of M. tuberculosis using ELISA. The antibody response to the three antigens were analyzed for 140 well-characterized active-TB patients, 30 pulmonary infection controls, and 40 healthy controls. Sensitivity and specificity for the three antigens were determined using ROC analysis. For all three antigens, the same numbers of TB cases and controls were taken. The cutoff was selected at the point which showed the best accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity by ROC analysis. A predictive value (PV) to define the probability of a disease is vital, as it provides the significance of a disease to characterize a patient for the particular disease from the patient's population (+PV) and a high PV is also needed to exclude the disease (Table 3). A positive likelihood ratio (+LR) means that the ratio between the probability of a positive test result given the presence of the disease and the probability of a positive test result given the absence of the disease; otherwise, the negative likelihood ratio (−LR) means the ratio between the probability of a negative test result given the presence of the disease and the probability of a negative test result given the absence of the disease, that is to say, a high +LR (+LR > 10) is needed to diagnose a disease, and a high −LR (−LR < 0.1) is also needed to exclude the disease. Hence, these parameters were also analyzed.

Table 3.

Immunoglobulin G reactivities against various antigens of M. tuberculosis at cutoff, determined by ROC analysisa

| Antigen | Cutoff | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | +PV (%) | −PV (%) | +LR | −LR | Area under ROC curve |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPD | 0.1323 | 66.7 | 74.3 | 69 | 72.2 | 2.59 | 0.45 | 0.712 |

| CFP-10–ESAT-6 | 0.2937 | 65.0 | 91.4 | 86.7 | 75.3 | 7.58 | 0.38 | 0.829 |

| CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ | 0.1193 | 73.3 | 94.3 | 91.7 | 80.5 | 12.83 | 0.28 | 0.862 |

+PV, positive predictive value; −PV, negative predictive value; +LR, positive likelihood ratio; −LR, negative likelihood ratio.

We observed antibody sensitivity of 66.7% and specificity of 74.3% for PPD, sensitivity of 65% and specificity of 91.4% for CFP-10–ESAT-6, and sensitivity of 73.3% and specificity of 94.3% for CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′, using the cutoff determined by ROC analysis (Table 3). The +LR of CFP-10–ESAT-6 and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were 7.58 and 12.83, respectively. We can conclude that if the antibody response to CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ is positive, the patient may be infected with TB. The sensitivity of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ was the highest (73.3%) for the three antigens used in this study, with a specificity of 94.3%. We noticed an antibody response to CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ for 10 patients who did not show an antibody response to both PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6; meanwhile, the antibody response to CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ was shown for only four controls, all of whom were the pulmonary infection cases (Table 4). Antibody responses to both PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6 were increase in non-TB pulmonary infection cases and in the healthy controls. We noted a slightly decreased sensitivity to CFP-10–ESAT-6 (65%) in comparison with that to PPD (66.7%) for active-TB patients; however, PPD results showed less specificity (74.3%) than CFP-10–ESAT-6 results (91.4%). Furthermore, the areas under the ROC curves were compared for the three antigens (Table 3 and Fig. 4); it was highest for CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ (0.862), followed by CFP-10–ESAT-6 (0.829) and PPD (0.712). According to the ROC analysis, there was a statistically significant difference between PPD detection and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ detection (P = 0.005) in pairwise comparison of ROC curves. Likewise, there was a statistical difference between PPD detection and CFP-10–ESAT-6 detection (P = 0.029) in pairwise comparison of ROC curves. Although the difference between CFP-10–ESAT-6 detection and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ detection was not statistically significant (P = 0.491), the sensitivity and specificity of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were better than those of CFP-10–ESAT-6. Therefore, our data indicated that CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ not only would significantly increase the sensitivity but also would maintain higher specificity, which may be more valuable for the clinical diagnosis of TB patients.

Table 4.

Positive cases in the present study detected with various antigens of M. tuberculosis

| Antigen | No. of positive results (no. tested) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TB group | Controls |

||

| Pulmonary infection cases | Healthy controls | ||

| PPD | 93 (140) | 13 (30) | 5 (40) |

| CFP-10–ESAT-6 | 91 (140) | 5 (30) | 1 (40) |

| CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ | 103 (140) | 4 (30) | 0 (40) |

Fig 4.

Area under the ROC curve for three antigens with sera from TB patients. The area under the ROC curve was highest for CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ (0.862), followed by CFP-10–ESAT-6 (0.829) and PPD (0.712). According to the ROC analysis, there was a statistically significant difference between PPD detection and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ detection (P = 0.005) in a pairwise comparison of ROC curves. Likewise, there was a statistical difference between PPD detection and CFP-10–ESAT-6 detection (P = 0.029). Although the difference between CFP-10–ESAT-6 detection and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ detection was not statistically significant (P = 0.491), the sensitivity and specificity of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ were better than those of CFP-10–ESAT-6.

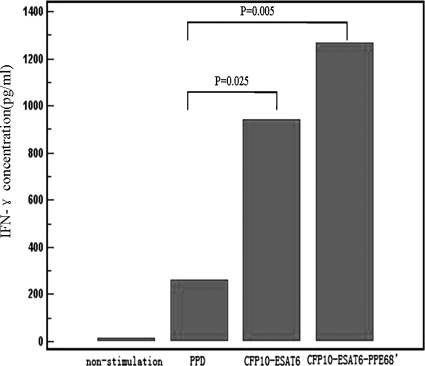

Immunogenicities of the fusion proteins.

Whole-blood samples we had collected from 60 active-TB patients were randomly selected and stimulated by PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ (Fig. 5). The levels of IFN-γ in all samples without antigen stimuli were below 20 pg/ml (14.1 ± 3.7 pg/ml) but significantly increased to 1,272.8 ± 140.1 pg/ml after CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ stimulation, compared to 263.4 ± 34.1 pg/ml after PPD stimulation and 941.3 ± 74.5 pg/ml after CFP-10–ESAT-6 stimulation. Analysis of IFN-γ levels for active-TB patients suggested there was a remarkable correlation between the immunodominant antigen of M. tuberculosis and the IFN-γ level. The IFN-γ level in samples activated by CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ was significantly higher than that in those activated by PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6 (P < 0.05).

Fig 5.

Immunogenicities of PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ in TB patients. The levels of IFN-γ in all samples without antigen stimuli were below 20 pg/ml (14.1 ± 3.7 pg/ml) but increased significantly to 1,272.8 ± 140.1 pg/ml after CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ stimulation, compared to 263.4 ± 34.1 pg/ml after PPD stimulation and 941.3 ± 74.5 pg/ml after CFP-10–ESAT-6 stimulation. The IFN-γ level in samples activated by CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ was significantly higher than that in samples activated by PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6 (P < 0.05).

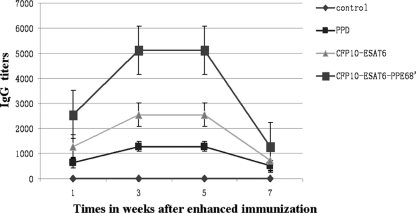

Antibody responses of mice.

Serum IgG antibodies in C57BL/6 mice against M. tuberculosis antigens were determined by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 6, the serum samples from the immunized mice showed a significant level of anti-M. tuberculosis IgG activity within 1 week after primary immunization, with a further increase after boosting. The CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′-treated mice group produced the highest IgG-specific response, while mice vaccinated with saline produced no antigen-specific antibody. Total IgG titers of mice vaccinated with CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ remained high at >5,000 between 3 and 5 weeks after primary immunization, whereas all of the others were no more than 2,000 in the 7 weeks after primary immunization. These findings indicated that strong, long-term humoral immunity was induced by CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′.

Fig 6.

Titers of IgG of mice immunized with PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′. The total IgG titers of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ remained high at >5,000 between 3 and 5 weeks after enhanced immunization; those for the other groups were no more than 1,000 in the 7 weeks after enhanced immunization. Means and standard errors are shown.

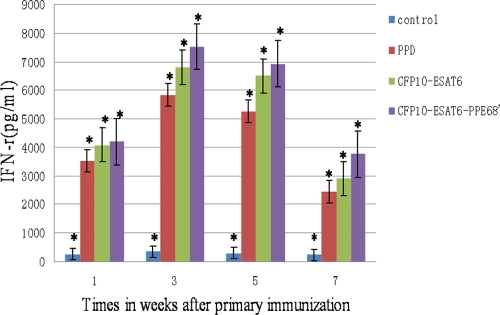

Antigen-specific IFN-γ production of mice.

In order to assess the immunogenicities of different proteins, we analyzed the levels of IFN-γ in immunized mice using ELISA after 1 weeks, 3 weeks, 5 weeks, and 7 weeks. As shown in Fig. 7, the highest antigen-specific IFN-γ response was observed for CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′-immunized mice and lasted a long time. IFN-γ levels of the mouse group vaccinated with saline were lower than 50 pg/ml.

Fig 7.

Level of antigen-specific IFN-γ. C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′. The control group was immunized with saline. IFN-γ levels were measured in triplicate by ELISA. The results are expressed as means ± SD. The IFN-γ levels of the CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′-immunized mouse group was high at >6,500 pg/ml between 3 and 5 weeks. ∗, P < 0.05 versus results for the control. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

DISCUSSION

Active TB is a seriously contagious disease and leads to the spread of M. tuberculosis. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment of TB patients are crucial for the control of TB spread. Serodiagnosis of active TB is a simple and rapid test method. Various studies have been undertaken to develop a serodiagnostic test using proteins of M. tuberculosis which are known to be immunodominant and early markers for TB (19). The antigens selected for our study have been reported to be strong targets for the humoral and cell-mediated immune response.

Comparative genomics analysis has revealed that the region of difference 1(RD-1) of M. tuberculosis is absent from all strains of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). RD-1 presents in all virulent members of the M. tuberculosis and M. bovis (8). Several antigenic proteins of M. tuberculosis encoded by genes located in RD1 have potential for specific diagnosis of TB. The best-studied RD1 proteins are culture filtered protein 10 (CFP-10) and early secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein (ESAT-6), both of which elicit strong T-cell and B-cell responses in experimental animals and humans (1, 3). CFP-10 (encoded by Rv3874) and ESAT-6 (encoded by Rv3875), secreted by M. tuberculosis, are encoded within the region of difference 1 (RD-1) of the M. tuberculosis genome. They are closely correlated with immunogenicity and virulence of M. tuberculosis. CFP-10 and ESAT-6 might be biologically active molecules in vivo when they form a 1:1 heterodimeric complex (7, 28). Several studies have reported that RD1-based (ESAT-6 and/or CFP-10) gamma interferon (IFN-γ) assays have higher specificity than the TST and are less influenced by previous BCG vaccination (21, 27). PPE68 (encoded by Rv3873), encoded within the region of difference 1 (RD-1), is thought to be associated with the cell surface of M. tuberculosis. Okkels et al. (25) reported that PPE68 is a potent T cell antigen recognized by M. tuberculosis-infected individuals. A delayed-type hypersensitivity response to PPE68 was observed in guinea pigs infected with M. tuberculosis (16), suggesting that PPE68 may be a significant immunogenic component of the RD-1 region. PPE68 does not interfere with the secretion and immunogenicity of CFP-10 and ESAT-6. Demangel et al. (4) reported that CFP-10 and ESAT-6 expression in whole-cell lysates and secretion in the culture supernatant were comparable in PPE68 and BCG RD1 suggesting that PPE68 does not participate in the secretion of these antigens. Moreover, the CFP-10- and ESAT-6-specific IFN-γ responses elicited by PPE were similar to those induced by BCG::RD1 (BCG complemented with RD-1), whereas no cellular response to these antigens was detected in BCG-vaccinated animals. Therefore, the immunogenicity of CFP-10 and ESAT-6 appears to be independent of PPE68 expression. The findings that PPE68, like ESAT-6 and CFP-10, can induce potent Th-1 cell responses and is also a potent T-cell antigen recognized by M. tuberculosis-infected individuals illustrates the abundance of cellular immune targets in the RD-1 region. For this reason, PPE68 could probably be used as a specific diagnostic marker to differentiate active tuberculosis patients from BCG-vaccinated individuals. Taken together, these results show that the genes encoding CFP-10, ESAT-6, and PPE68 are situated adjacent to each other in the M. tuberculosis genome, suggested that they may constitute a gene cluster that encodes a new transporter system in M. tuberculosis. The frequent occurrence of T-cell determinants in this region suggests that this functional unit may be particularly active in interacting with the host immune system and may play an important role in host-pathogen interactions (31).

In the present study, the fusion proteins were purified by using a HisTrap HP affinity column (GE Healthcare). The HisTrap HP column is supplied precharged with Ni2+ ions. In general, Ni2+ is the preferred metal ion for purification of recombinant histidine-tagged proteins. Imidazole at low concentrations is commonly used in the binding and the wash buffer to minimize binding of host cell proteins, while imidazole at high concentrations is normally used in the elution buffer to maximize eluting with histidine-tagged proteins. The imidazole concentration must therefore be optimized to ensure the best balance of high purity. The optimal concentration is different for different histidine-tagged proteins. Through a series of experiments using different concentrations of binding, washing, and elution buffers, we observed that 30 mM imidazole in binding and washing buffers is good for the fusion proteins we prepared for the present study. Three different concentrations of elution buffers (300 mM imidazole, 400 mM imidazole, and 500 mM imidazole) have been chosen to elute the fusion proteins. To take CFP-10–ESAT-6 for an example, other proteins' bands were seen on the SDS-PAGE gel in 400 mM imidazole elution buffer. Although 500 mM imidazole elution buffer is optimal in the manufacturer's protocol, the targeted protein band was lighter than that in 300 mM imidazole elution buffer on the gel, suggesting that the concentration of the protein after eluting was low. Thus, 300 mM imidazole in elution buffer is an optimal choice in our study.

Nassau et al. (23) have established an ELISA method to detect anti-TB antibodies in serum samples from TB patients since 1976; the ELISA method has been widely used in serological diagnosis of TB. The coating antigen is the key factor for the test results. So far, there are still no commercially available serodiagnostic tests for active TB with acceptable sensitivity and specificity for routine laboratory use. Any single M. tuberculosis antigen is not enough to be used to cover the antibody profiles of active-TB patients, but combinations of antigens may yield improved level of sensitivity without affecting specificity because of infection with M. tuberculosis passing through several stages with different compositions of antibodies. In order to detect the antibody response in the serum samples, we established an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with PPD (20), CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ used as coated proteins, although as a purified protein derivative, tuberculin PPD is a mixture of mycobacterial antigens and most of the PPD components are shared between nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and the Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine strains. The sensitivity of PPD in our study was 66.7%, with only 74.3% specificity. Antibodies in 18 cases of the control group (n = 70 total) can react with PPD, even including 5 cases in the healthy control group (n = 40). The sensitivity of CFP-10–ESAT-6 was 65%, which was lower than the sensitivity for PPD, and yet its specificity was 91.4%. The sensitivity of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ was the highest (73.3%), with a specificity of 94.3%. Antibodies in 103 cases of the TB group (n = 140 total) show a response to CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′. The 10 patients identified by CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ did not show an antibody response to both PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6. Our data suggested that PPE68′ enhanced the immunological response to CFP-10–ESAT-6. Without reducing specificity, the multiple-antigen combination with high specificity can improve sensitivity in detection. Therefore, multiple-antigen combination tests may be more useful for the development of diagnostic antibody tests because of many antigens inducing serological responses (6, 26, 30). Our data showed that both the sensitivity and the specificity were increased with the use of CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′.

Cell-mediated immunity plays a key role in the host defense against M. tuberculosis infection (11). IFN-γ is an important indicator for the Th1-type cellular immune response and is an essential mediator of the protective immune response to TB (15, 36). With the stimulation of the purified fusion protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′, the IFN-γ levels in the peripheral blood from 60 randomly selected confirmed active-TB patients were much higher than those stimulated by PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6. The level of IFN-γ stimulated by PPD was the lowest in the study. Without the stimulation of the three proteins, the IFN-γ level was very low. These results indicated that CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ could stimulate high-level release of IFN-γ from sensitized T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of TB patients. Therefore, we conclude that CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ might be a promising stimulator of Th1-type cellular immune response against TB.

The C57BL/6 mouse is the animal most commonly used as an in vivo model for M. tuberculosis infection. In this study, C57BL/6 mice were immunized with PPD, CFP-10–ESAT-6, and CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ to provide experimental data to evaluate the effect of these proteins in M. tuberculosis. The persistence of the M. tuberculosis-specific serum IgG antibody response, which is dependent on the generation of immunological memory, was indicative of its ability to confer long-term protection. According to our data after immunization, we found that the specific antibody titer and the IFN-γ level of the three groups were increased compared to those of the control group, which was immunized with saline. Immunization of C57BL/6 mice with CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ induced a robust serum specific immune response and lasted as long-term humoral immunity compared to results with PPD and CFP-10–ESAT-6 (Fig. 6 and 7).This findings suggested that when the fusion protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ as a targeted pathogenic agent challenges the body, immunological memory can be induced quickly.

CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ of M. tuberculosis was first successfully expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3). Our ELISA results clearly demonstrated that the purified fusion protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ has both sensitivity and the specificity better than those of CFP-10–ESAT-6 and PPD in active-TB patients and controls. Various articles (9, 13, 14, 33) have reported the utility of an M. tuberculosis-specific enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay for the diagnosis of TB. The developed tests show good sensitivity and specificity and are promising for TB diagnosis. However, the limitation of this method is that it takes 2 days to obtain the results, in contrast to indirect ELISA, which takes only 4 h for the final diagnosis. Thus, it seems that the purified fusion protein CFP-10–ESAT-6–PPE68′ could be considered as a candidate coated antigen for rapid diagnostic tests for TB and also as a potential candidate for use as an efficacious antituberculosis subunit vaccine or in prime-boosting regimens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by a grant from the public welfare research project of Sichuan province (no. 2008SZ0106).

We are grateful to Qingcui Zeng for providing well-diagnosed serum samples from active-TB patients from Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital. We also thank Yang Gao for providing the serum samples from control subjects from Xindu People's Hospital, Chengdu, Sichuan, China.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Arend SM, et al. 2000. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10 and to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect. Immun. 68:3314–3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berthet FX, Rasmussen PB, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Gicquel B. 1998. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10). Microbiology 144:3195–3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brusasca PN, et al. 2001. Immunological characterization of antigens encoded by the RD1 region of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome. Scand. J. Immunol. 54:448–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Demangel C, et al. 2004. Cell envelope protein PPE68 contributes to Mycobacterium tuberculosis RD1 immunogenicity independently of a 10-kilodalton culture filtrate protein and ESAT-6. Infect. Immun. 72:2170–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dillon DC, et al. 2000. Molecular and immunological characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CFP-10, an immunodiagnostic antigen missing in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3285–3290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fujita Y, Ogata H, Yano I. 2005. Clinical evaluation of serodiagnosis of active tuberculosis by multiple-antigen ELISA using lipids from Mycobacterium bovis BCG Tokyo 172. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 43:1253–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo S, Bao L, Qin ZF, Shi XX. 2010. The CFP-10/ESAT-6 complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis potentiates the activation of murine macrophages involvement of IFN-γ signaling. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 199:129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hart PD, Sutherland I. 1977. BCG and vole bacillus vaccines in the prevention of tuberculosis in adolescence and early adult life. Br. Med. J. 2:293–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jafari C, Lange C. 2008. Suttons's law: local immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis. Infection 36:510–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuman G, et al. 2010. Serodiagnostic efficacy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis 30/32-kDa mycolyl transferase complex, ESAT-6, and CFP-10 in patients with active tuberculosis. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 58:57–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lu J, et al. 27 February 2011. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy against murine tuberculosis of a prime-boost regimen with BCG and a DNA vaccine expressing ESAT-6 and Ag85A fusion protein. Clin. Dev. Immunol. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kamath AT, Feng CG, MacDonald M, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. 1999. Differential protective efficacy of DNA vaccines expressing secreted proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 67:1702–1707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim SH, et al. 2008. Diagnosis of central nervous system tuberculosis by T-cell-based assays on peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid mononuclear cells. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:1356–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kösters K, et al. 2008. Rapid diagnosis of CNS tuberculosis by a T-cell interferon-gamma release assay on cerebrospinal fluid mononuclear cells. Infection 36:597–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lightbody KL, et al. 2004. Characterisation of complex formation between members of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex CFP-10/ESAT-6 protein family: towards an understanding of the rules governing complex formation and thereby functional flexibility. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238:255–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu XQ, et al. 2004. Evaluation of T cell responses to novel RD1 and RD2 encoded Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene products for specific detection of human tuberculosis infection. Infect. Immun. 72: 2574–2581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luo Y, et al. 2009. Fusion protein Ag85B-MPT64190–198-Mtb8.4 has higher immunogenicity than Ag85B with capacity to boost BCG-primed immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Vaccine 27:6179–6185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lyashchenko K, et al. 1998. Use of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-specific antigen cocktails for a skin test specific for tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 66:3606–3610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Malen H, Softeland T, Wiker HG. 2008. Antigen analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv culture filtrate proteins. Scand. J. Immunol. 67:245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martins MV, et al. 2007. The level of PPD-specific IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells in the blood predicts the in vivo response to PPD. Tuberculosis 87:202–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mazurek GH, et al. 2001. Comparison of a whole-blood interferon-g assay with tuberculin skin testing for detecting latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. JAMA 286:1740–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mukhopadhyay S, Balaji KN. 2011. The PE and PPE proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 91:441–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nassau E, Parsons ER, Johnos GD. 1976. The detection of antibodies to Mycobacterium tuberculosis by microplate enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Tubercle 57:67–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noordhoek GT, et al. 1994. Sensitivity and specificity of polymerase chain reaction for detection of M. tuberculosis, a blind comparison study among seven laboratories. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:277–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okkels LM, et al. 2003. PPE protein (Rv3873) from DNA segment RD1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: strong recognition of both specific T-cell epitopes and epitopes conserved within the PPE family. Infect. Immun. 71:6116–6123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Okuda Y, et al. 2004. Rapid serodiagnosis of active pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis by analysis of results from multiple antigen-specific tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1136–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pai M, et al. 2005. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in health care workers in rural India: comparison of a whole-blood interferon-γ assay with tuberculin skin testing. JAMA 293:2746–2755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Renshaw PS, et al. 2002. Conclusive evidence that the major T-cell antigens of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex ESAT-6 and CFP-10 form a tight, 1:1 complex and characterization of the structural properties of ESAT-6, CFP-10, and the ESAT-6-CFP-10 complex: implications for pathogenesis and virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 277:21598–21603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rustomjee R, et al. 2008. Early bactericidal activity and pharmacokinetics of the diarylquinoline TMC 207 in pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:2831–2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steingart KR, et al. 2007. Commercial serological antibody detection tests for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 4:e202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tekaia F, et al. 1999. Analysis of the proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in silico. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:329–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teutschbein J, et al. 2009. A protein linkage map of the ESAT-6 secretion system 1 (ESX-1) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol. Res. 164:253–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas MM, et al. 2008. Rapid diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis meningitis by enumeration of cerebrospinal fluid antigen-specific-T-cells. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 12:651–657 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thornton CG, MacLellan KM, Brink TL, Jr, Passen S. 1998. In vitro comparison of NALC-NaOH, Tween 80, and C18-carboxypropylbetaine for processing of specimens for recovery of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3558–3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization 2009. WHO report 2009: global tuberculosis control: epidemiology, strategy, financing. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu X, et al. 2011. Clinical evaluation of a homemade enzyme-linked immunospot assay for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis in China. Mol. Biotechnol. 47:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]