Abstract

The emergence of resistance presents a debilitating change in the management of infectious diseases. Currently, the temporal relationship and interplay between various mechanisms of drug resistance are not well understood. A thorough understanding of the resistance development process is needed to facilitate rational design of countermeasure strategies. Using an in vitro hollow-fiber infection model that simulates human drug treatment, we examined the appearance of efflux pump (acrAB) overexpression and target topoisomerase gene (gyrA and parC) mutations over time in the emergence of quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Drug-resistant isolates recovered early (24 h) had 2- to 8-fold elevation in the MIC due to acrAB overexpression, but no point mutations were noted. In contrast, high-level (≥64× MIC) resistant isolates with target site mutations (gyrA S83L with or without parC E84K) were selected more readily after 120 h, and regression of acrAB overexpression was observed at 240 h. Using a similar dosing selection pressure, the emergence of levofloxacin resistance was delayed in a strain with acrAB deleted compared to the isogenic parent. The role of efflux pumps in bacterial resistance development may have been underappreciated. Our data revealed the interplay between two mechanisms of quinolone resistance and provided a new mechanistic framework in the development of high-level resistance. Early low-level levofloxacin resistance conferred by acrAB overexpression preceded and facilitated high-level resistance development mediated by target site mutation(s). If this interpretation is correct, then these findings represent a paradigm shift in the way quinolone resistance is thought to develop.

INTRODUCTION

Drug-resistant microorganisms have become a major health problem worldwide. A number of these organisms have acquired mechanisms that make them resistant to nearly all currently available antimicrobial agents, compromising the clinical utility of these agents (3, 19). A more comprehensive understanding of the resistance development process could help overcome resistance emergence.

The quinolones are a class of broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents associated with a low incidence of adverse effects. In view of these appealing qualities, the heavy prescription of quinolones has led to increased resistance (3, 13). Bacteria can become resistant to quinolones by different mechanisms. One of these mechanisms is the acquisition of a mutation(s) at the drug binding site, reducing the affinity of the agent for its target. For example, clinically relevant quinolone resistance can be attributed to mutations in the genes encoding the drug targets DNA gyrase (gyrA and/or gyrB) and topoisomerase IV (parC and/or parE) (15, 32). Another common mechanism of drug resistance is the active extrusion of the antimicrobial agents by efflux pumps (e.g., AcrAB-TolC) (41). This process decreases the drug concentration reaching the target.

Our present understanding of the resistance development process is mostly based on data derived from surveillance studies or retrospective studies performed on clinical isolates (1, 7, 27). While these studies are widely accepted for detecting resistance emergence from the epidemiological standpoint, they are not very informative on the process of resistance development. These analyses are mostly endpoint observations, when the bacteria have developed high-level (clinical) resistance to the antimicrobial agent, and seldom take into account the changes (if any) occurring during the resistance development process. Even studies specifically designed to determine the order of mutation acquisition (14, 30) reported only the “endpoint” selected mutants and not any transient alterations. In addition, different mechanisms of resistance are typically studied individually, without considering potential interactions among them. For example, in the case of quinolone resistance, mutations in the quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR) of the gyrase and topoisomerase IV genes, along with efflux pump overexpression, have been reported in clinical isolates (9, 10, 35). A study by Morgan-Linnell et al. reported mutations in gyrase and/topoisomerase IV in 100% of the high-level-resistant Escherichia coli clinical isolates, whereas overproduction of the efflux pump (AcrA) contributed approximately 33% to the overall quinolone resistance (28). Most of these reports suggested that efflux pumps conferred only low-level resistance (2- to 8-fold increase in MIC values), but how this low-level resistance impacts clinical resistance was unclear (4, 17, 33).

This study was designed to gain a deeper understanding of the drug resistance development process. To study the contributions and interplay of resistance mechanisms, we examined different mechanisms of drug resistance at various times during resistance development. These studies were performed with levofloxacin and E. coli using simulated human-like drug exposures in an in vitro hollow-fiber infection model (HFIM). Specifically, we examined the temporal interplay of two quinolone resistance mechanisms: efflux pump (acrAB) expression and topoisomerase target gene (gyrA and parC) mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial agents.

Levofloxacin hydrochloride was purchased from Waterstone Technologies (Carmel, IN). Moxifloxacin powder was a gift from Bayer Pharmaceuticals (West Haven, CT). A stock solution was prepared by dissolving the powder in sterile water and stored in aliquots at −70°C. Prior to each investigation, an aliquot of the stock solution was thawed and diluted with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Ca-MHB) (BBL, Sparks, MD) or sterile water.

Microorganisms.

Three strains of E. coli were used. A laboratory standard strain (MG1655) and two isogenic derivatives (ΔacrAB and ΔacrR) were investigated. In the ΔacrAB strain, the gene encoding a major efflux pump mediating quinolone resistance (i.e., acrAB) was deleted. In the ΔacrR strain, the local repressor gene (acrR) was deleted, resulting in stable overexpression of acrAB. Strain constructions and gene deletions have been described (25) and verified experimentally. These bacteria were stored at −70°C in Protect storage vials (Key Scientific Products, Round Rock, TX). Fresh isolates were subcultured twice on 5% blood agar plates (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, CA) for 24 h at 35°C prior to each experiment.

Susceptibility studies and measurement of relative expression of acrAB.

MICs were determined in Ca-MHB by using a modified broth dilution method as described by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (6) and as detailed previously (36). A quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) method was used to investigate the relative transcription levels of acrA and acrB in various bacterial strains. Total RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy minicolumns (Qiagen [Valencia, CA] RNeasy kit). Reverse transcription was performed using a GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with random hexamers. The cDNA samples were analyzed in triplicate on an ABI Prism 7000 (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR green chemistry (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification of the samples was performed by the ΔΔCT method using 16S rRNA as an internal control and the parent MG1655 as the reference strain (21). The sequences of the primers used were as follows: acrA forward, 5′-ATTGGTAAGTCGAACGTGACG-3′, and reverse, 5′-AACTTAATGCCGTCACTGGTG-3′; acrB forward, 5′-GATTACCATGCGTGCAACAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TCTGCAAGCAACTGGTTACG-3′; 16S rRNA forward, 5′-CAGCCACACTGGAACTGAGA-3′, and reverse, 5′-GTTAGCCGGTGCTTCTTCTG-3′. For selected levofloxacin-resistant isolates, the relative expression of mdfA and norE was also performed in a similar fashion (37).

Hollow-fiber infection model studies.

Fluctuating serum drug concentrations (non-protein bound) were simulated in the HFIM to investigate bacterial responses to clinically relevant drug exposures. The schematics of the HFIM were described in detail previously (38, 39). The simulated half-life for levofloxacin was 5 to 7 h (5, 12). On the day of the experiment, a few colonies of bacteria were inoculated in Ca-MHB and incubated at 35°C until they reached log-phase growth. Approximately 20 ml of bacteria (1 × 105 CFU/ml) was introduced into the extracapillary space of the hollow-fiber cartridge (FiberCell Systems, Inc., Frederick, MD). The experimental setup was maintained at 35°C in a humidified incubator for the duration of the experiment. Levofloxacin was administered once daily to the HFIM. To ascertain the pharmacokinetic profiles simulated in the HFIM, serial samples (500 μl) were obtained in duplicate on different days from the circulating loop of the system. The levofloxacin concentrations in these samples were assayed by a validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method. A one-compartment linear model was fitted to the observed concentration-time profiles using the ADAPT II program (8).

The bacterial burden was serially assessed by sampling (500 μl) daily in duplicate from the extracapillary space of the hollow-fiber cartridge. Samples were washed with sterile saline, centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min, and serially diluted (10×) before plating (50 μl) on drug-free Mueller-Hinton agar II (MHA) (BBL, Sparks, MD) plates to quantify the total bacterial population. To detect isolates with different magnitudes of reduced susceptibility, agar plates supplemented with levofloxacin at various multiples of the MIC for the bacterial strain (e.g., 2× MIC, 4× MIC, and 64× MIC) were used. It is generally accepted that efflux pump overexpression causes a 2- to 8-fold increase in the quinolone MIC, so 2× MIC-supplemented plates were utilized to detect bacterial populations with reduced susceptibility, likely due to efflux pump overexpression. In addition, 4× MIC and 64× MIC levofloxacin-supplemented plates were used to further select for isolates, most likely with single or multiple target site mutations. At least a 4-fold increase in the MIC is expected in single (gyrA) mutants, and more than 64× MIC elevation is expected in isolates with more than 1 target site mutation (29). Drug-free plates were incubated for 24 h, and levofloxacin-supplemented MHA plates were incubated for up to 72 h (if required) at 35°C before the CFU were enumerated visually. The theoretical lower limit of detection was 400 CFU/ml. The drug-resistant isolates recovered were evaluated for the mechanism(s) of resistance using sequencing and qRT-PCR analysis. Since a transient increase in the expression of acrAB could reverse without sustained selective antimicrobial pressure, these isolates were kept on levofloxacin-supplemented agar plates at the same concentration as they were initially plated until the analyses were performed.

A once-daily fixed-dosage strategy was utilized initially in HFIM to study the development of drug resistance in the parent strain. However, we were unable to detect the emergence of high-level resistance mutants consistently above the reliable limit of detection (data not shown). The selective pressure was thought to be inadequate for the amplification of highly resistant isolates. Hence, in an attempt to select for high-level resistance, a sequentially escalating dosing exposure was used. The dose exposure was increased every day, giving a progressively higher selective pressure every 24 h to keep up with low- to intermediate-level resistance developed over time. To elucidate the impact of efflux pump deletion on resistance emergence, the parent and ΔacrAB strains were compared using escalating dosing (the ratio of the area under the concentration-time profile to the MIC [AUC/MIC ratio]) exposures in the HFIM. Our preliminary time course studies showed no significant difference in fitness and growth of the ΔacrAB strain compared to the parent strain (data not shown), which is in agreement with results published previously (18, 22). Hence, it was deemed unlikely that the results of the ΔacrAB studies would be confounded by the fitness cost. Since preliminary susceptibility studies demonstrated that the ΔacrAB strain had a 4-fold reduction in the MIC compared to the parent strain, comparisons were made in two ways. First, a comparison was made using similar AUCs (approximately 0.6 mg · h/liter) for the two strains without adjusting for the MIC difference. This drug exposure was selected based on the previous dose-ranging studies with a fixed-dosage strategy in the parent E. coli strain. Resistance emergence was found to be associated with this drug exposure, allowing us to examine the impact (if any) of efflux pump deletion on resistance development. Second, a comparison was made after adjusting for the MIC difference between the two strains (i.e., using a similar AUC/MIC ratio of approximately 30).

Gene amplification and sequencing.

The QRDR regions of gyrA and parC were amplified by PCR and sequenced for isolates recovered from the levofloxacin-supplemented agar plates at various time points from the HFIM. Details of the amplification method were reported previously (36). Although mutations in gyrB or parE have been identified in clinical isolates, they have not been validated to cause MIC changes, and hence, these genes were not analyzed (28).

Statistical analysis.

Relative expression of efflux pump genes in resistant isolates recovered from HFIM and differences in intracellular drug accumulation in isogenic derivatives were compared to those of the parent strain using Student's t test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Deletion of the efflux pump is associated with an increase in the susceptibility and intracellular accumulation of quinolones.

Levofloxacin MICs were 0.032 mg/liter for the parent strain and 0.008 mg/liter for the ΔacrAB strain and 0.064 mg/liter for the ΔacrR strain. Disruption of acrAB has been shown to increase the susceptibility of various quinolones by 2- to 8-fold (42). Two-fold elevation in the MIC in the ΔacrR strain is also consistent with the previous studies demonstrating low-level resistance with efflux pump overexpression (4, 33). As additional confirmatory studies, the relative expression of acrAB and intracellular drug accumulation were measured in these three strains. The intracellular quinolone concentration correlated negatively with the relative expression of acrAB. Compared to the isogenic parent, deletion of acrAB was associated with significantly higher intracellular accumulation of levofloxacin and moxifloxacin (P < 0.001) (data not shown). In the ΔacrR strain, the intracellular concentrations were lower (P < 0.05) than in the isogenic parent, supporting the idea that overexpression of acrAB was associated with a decrease in the quinolone concentration within the bacterial cells.

Efflux pump overexpression is an early step in quinolone resistance development.

In all three E. coli strains investigated, the mutation frequency was observed to be less than 1 × 10−9. At this frequency, the starting inocula used in HFIM experiments (approximately 2 × 106 CFU) were deemed to be homogeneous and unlikely to contain any preexisting mutants. For each experiment, a sample of the starting inoculum (500 μl) was also plated on drug plates supplemented with levofloxacin at 2× MIC, and we found no colonies. Our pilot studies also confirmed that the daily drug exposure, but not the dosing frequency, was most closely linked to observed bacterial behavior with respect to population regrowth or suppression (data not shown). Hence, once-daily dosing was used in all subsequent experiments. Simulated levofloxacin exposures were satisfactorily achieved in all HFIM experiments (r2 ≥ 0.9); half-lives were within the target of 5 to 7 h (data not shown).

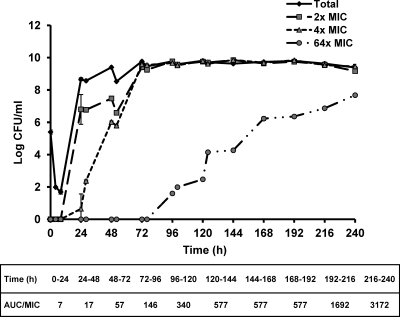

The bacterial growth response to sequentially escalating levofloxacin exposures is shown in Fig. 1. The drug exposures (expressed as the AUC/MIC ratio) achieved daily are also shown and ranged from approximately 7 to 3,200. As expected, the consistent selective pressure exerted by the sequentially escalating dosing strategy led to a progressive increase in the resistant population (recovered from agar plates supplemented with levofloxacin at 64× MIC) over time.

Fig 1.

Bacterial response to sequentially escalating levofloxacin exposures in HFIM (starting with the parent E. coli strain). The data are shown as means ± standard deviations.

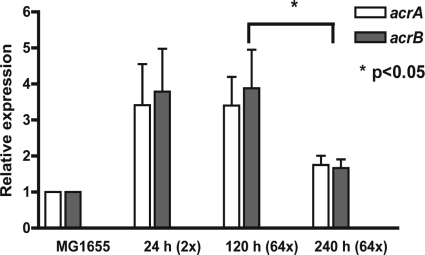

To study the temporal appearance of resistance mechanisms, isolates were recovered from levofloxacin-supplemented agar plates at three different time points: early (24 h), intermediate (120 h), and late (240 h). These recovered isolates were retested for levofloxacin susceptibility. The results of these susceptibility studies and sequencing analyses are shown in Table 1. The analysis of acrAB transcription in levofloxacin-resistant isolates revealed at least three distinct profiles (Fig. 2). The resistant isolates recovered early (24 h) had primarily 2× to 6× MIC elevation with no point mutation and a 2- to 8-fold increase in acrAB expression. High-level (≥64× MIC) resistant isolates recovered from an intermediate time point (120 h) were found to have target site mutation at gyrA (S83L), and the relative expression levels of acrA and acrB remained high (2- to 8-fold). The resistant isolates recovered at a later time point (240 h) had ≥100-fold increase in the MIC with a point mutation(s) in QRDR (gyrA S83L with and without parC E84K). Regression of acrAB overexpression compared to isolates recovered at 120 h was observed (P < 0.05). When the results from different isolates obtained from the same starting population were pooled, the overall efflux pump expression was seen to increase only transiently, suggesting that efflux pump expression might revert to baseline when no survival advantage was present. Since efflux pumps are constitutively expressed at baseline, these results suggested that upregulation of efflux pump gene transcription played an essential role in the early stages of resistance development until another resistance mechanism(s) was acquired.

Table 1.

Levofloxacin MIC fold elevation and mutations present in gyrA and parC in resistant isolates recovered from HFIM studies (starting with the parent E. coli strain)

| Time of recovery (h) | Concn of levofloxacin supplementation (× MIC) | Fold MIC elevation | gyrA mutation | parC mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 2 | 4 | NDa | ND |

| 24 | 2 | 4 | ND | ND |

| 24 | 2 | 4 | ND | ND |

| 24 | 2 | 6 | ND | ND |

| 24 | 2 | 3 | ND | ND |

| 24 | 2 | 6 | ND | ND |

| 120 | 64 | 188 | S83L | ND |

| 120 | 64 | 188 | S83L | ND |

| 120 | 64 | 125 | S83L | ND |

| 120 | 64 | 125 | S83L | ND |

| 120 | 64 | 47 | S83L | ND |

| 120 | 64 | 63 | S83L | ND |

| 240 | 64 | 250 | S83L | ND |

| 240 | 64 | 188 | S83L | E84K |

| 240 | 64 | 125 | S83L | ND |

| 240 | 64 | 188 | S83L | ND |

| 240 | 64 | 188 | S83L | ND |

| 240 | 64 | 188 | S83L | ND |

ND, not detected.

Fig 2.

Relative expression of acrAB in resistant isolates recovered from HFIM studies (starting with the parent E. coli strain) at various time points (n = 6). The data are shown as means and standard deviations.

Deletion of the efflux pump delays the emergence of quinolone resistance.

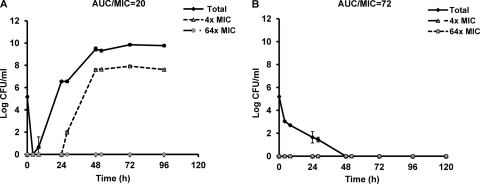

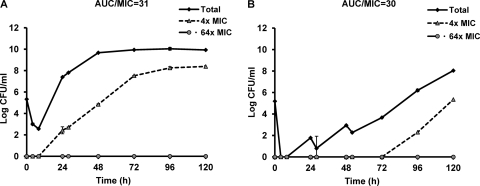

If overexpression of acrAB is the first mechanism to occur and this mechanism is required before topoisomerase gene mutations can accumulate, then the deletion of the acrAB genes would be expected to prevent or delay the appearance of topoisomerase gene mutations. To further elucidate the impact of efflux pump expression on resistance emergence, the parent and ΔacrAB strains were compared in the HFIM using escalating levofloxacin dosing exposures. In both strains, resistance emerged under low dosing exposures, and bacterial population suppression was observed with high dosing exposures (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3, a similar levofloxacin daily dose (AUC) resulted in suppression of the bacterial population in the ΔacrAB strain (AUC/MIC = 72), but regrowth was observed in the parent strain (AUC/MIC = 20). This result implied that susceptibility changes mediated by efflux pump disruption had a direct effect on the bacterial response under similar daily drug exposures. Subsequently, comparisons were made after adjusting for the MIC difference between the two strains. When the bacterial strains were exposed to a daily AUC/MIC ratio of approximately 30, we found a 72-h delay in the emergence of resistance in the ΔacrAB strain compared to the parent strain (Fig. 4). This result further substantiated the important role of efflux pumps early in the resistance development process.

Fig 3.

Bacterial responses to similar levofloxacin exposures (AUC, approximately 0.6 mg · h/liter) in parent (A) and ΔacrAB mutant (B) strains. The data are shown as means ± standard deviations.

Fig 4.

Bacterial responses to levofloxacin exposure (adjusted for MIC) in the parent strain (A) and the ΔacrAB mutant (B). The data are shown as means ± standard deviations.

To investigate an alternative pathway(s) by which bacteria acquired target site mutations in the absence of AcrAB, resistant isolates recovered from levofloxacin-supplemented agar plates at 120 h in the ΔacrAB experiment were further examined. All the isolates analyzed had 8- to 16-fold MIC elevation, as shown in Table 2. PCR and sequencing revealed gyrA mutation (S83L) in 2 out of 4 isolates. In the 2 isolates without gyrA mutation, the relative expression of two other efflux pumps (mdfA and norE) known to affect the quinolone MIC were found to be elevated relative to the parent strain (data not shown).

Table 2.

Levofloxacin MIC fold elevation and mutations in gyrA and/or parC in resistant isolates recovered from HFIM studies with the ΔacrAB strain

| Time of recovery (h) | Concn of levofloxacin supplementation (× MIC) | Fold MIC elevation | gyrA mutation | parC mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 | 4 | 16 | S83L | NDa |

| 120 | 4 | 16 | S83L | ND |

| 120 | 4 | 8 | ND | ND |

| 120 | 4 | 16 | ND | ND |

ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of drug resistance presents a debilitating challenge in the management of infectious diseases. Resistance to quinolones has increased as much as 50% in some parts of the world, leading to a conundrum in the use of this class of drugs (19). Thus, there is an urgent need to understand the process of resistance development and to develop effective countermeasure strategies. While the effect of efflux pump deletion on the acquisition of drug target mutations has been previously studied (34), this is the first study, to our knowledge, describing the interplay of the two resistance mechanisms using human-like selective pressures. Of the more than 40 known transporters in E. coli, only three (AcrAB-TolC, MdfA, and NorE) are known to affect the quinolone MIC in isogenic strains (42).

A previous study showed that efflux pumps played a role in quinolone resistance emergence in Streptococcus pneumoniae (16). In a nonneutropenic murine thigh infection model, a strain in which the efflux pump was overexpressed had a significantly higher mutation frequency to levofloxacin than the wild type. Furthermore, using an in vitro HFIM, Louie et al. demonstrated that the addition of an efflux pump inhibitor (reserpine) led to levofloxacin resistance suppression in a wild-type and an efflux pump-overexpressing S. pneumoniae strain (24). While these studies highlighted the role of efflux pumps, our study extended their work by demonstrating that efflux pump overexpression was the first and essential step in quinolone resistance development. In all the HFIM experiments conducted with the parent E. coli strain, whenever resistance emergence was observed, a large majority (27 out of 30) of the resistant isolates recovered at 24 h had acrAB overexpression (>2-fold increase) and no point mutation in the topoisomerase genes (data not shown). Based on these results, we concluded that early acrAB overexpression was unlikely to be a chance event. This initial increase in acrAB expression was independent of the dosing strategy, thus emphasizing the importance of efflux pumps in the early development of resistance. With a sustained selective pressure, high-level resistance eventually emerged as a consequence of overexpression of an efflux pump(s) working in concert with single point mutations in gyrA. These results indicated that early low-level levofloxacin resistance conferred by acrAB overexpression preceded high-level resistance mediated by a target site mutation(s). When a target site mutation(s) was acquired, we observed a regressing trend in the expression of the acrAB efflux pump. Lee et al. subjected a continuous culture of a wild-type E. coli strain to progressively increasing concentrations of norfloxacin in a bioreactor for 10 days and found isolates with low-level resistance for 6 to 8 days, and then highly resistant isolates were detected (20). They suggested a population-based antibiotic resistance mechanism based on indole as a cell-signaling molecule. While the authors reported gyrB and marR variants in highly resistant isolates, the resistance mechanisms in mutants with low-level resistance were not examined. Our study fills the gap by providing data to support the idea that in the initial stages of resistance emergence, efflux pump overexpression plays a critical role. Previous studies reported that overproduction of efflux pumps was found in approximately 30% of quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of E. coli (4, 28). Our study offers a novel insight to these observations. Resistant clinical isolates not demonstrating overexpression of an efflux pump could have been collected at a later time point during the course of infection; these isolates might have had transient overexpression and regressed to the constitutive baseline level. Our results highlighted the importance of the time factor in the study of resistance mechanisms; we showed that the most important resistance mechanism could change as resistance development progressed. Consequently, the pivotal role of efflux pumps in resistance development could have been underappreciated. Our results provided a framework for the interplay of the two mechanisms of resistance and the quintessential role mediated by these efflux pumps. Data from our study give a new perspective on the fundamentals and add to our current understanding of the drug resistance development process in bacteria.

Our attempts at disrupting efflux pump expression (using the ΔacrAB strain) showed a delay in the emergence of resistance. Our results further suggested that the regulation of efflux pumps might be multifactorial, since disrupting one efflux pump was not absolutely detrimental to resistance emergence. In the absence of the most important efflux pump, other efflux pumps could become dominant over time. In contrast to complete suppression of bacterial growth using reserpine (24), resistance emergence was delayed only 3 days in the strain in our study with the efflux pump deleted. These results are not surprising, as the efflux pumps in Gram-negative bacteria are more diverse and their functions are more difficult to disrupt than those in Gram-positive bacteria (23, 31). Another reason could be that reserpine is a nonspecific efflux pump inhibitor, whereas in our study, only one efflux pump was disrupted. Investigations in resistant isolates recovered from the ΔacrAB strain suggested other efflux pumps (mdfA and norE) might compensate for the lack of acrAB, eventually allowing target site mutation(s). These results are also supported by previous observations (22) and point to the extensive coordination exhibited by efflux pumps.

It should be noted that only the QRDRs of gyrA and parC were sequenced, and the possibility of mutations in gyrB and parE could not be excluded. However, multiple studies showed that gyrB and parE were not common target sites for mutation in Gram-negative pathogens (2, 11, 30, 40) and that gyrA mutation was the most common first mutational step in quinolone resistance. The in vitro model utilized in our studies also could not mimic in vivo conditions, such as the pathology of infection, host-defense mechanisms, virulence, and metabolic behavior of the pathogen. Although the regression in acrAB expression suggested the efflux pumps were overexpressed transiently, we did not sequence the acrR (the local repressor for acrAB) or the marR (the global repressor for acrAB) loci, and hence, the possibility of additional mutations could not be ruled out. A study by Marcusson et al. reported that mutations in acrR and marR were associated with high fitness cost and mutation in fluoroquinolone target genes might reverse the fitness cost by restoring the expression of a growth-limiting gene(s) controlled by marR (26).

Our results highlighted the importance of acrAB in the development of quinolone resistance in E. coli. These results suggested that inhibition of efflux pumps could lead to a delay in resistance emergence and that this presented a window of opportunity for potential intervention. The temporal interplay between the two main mechanisms of quinolone resistance suggests that resistance development in bacteria operates in a highly coordinated manner and that its regulation is multifactorial. If this interpretation is correct, then the results represent a paradigm shift in the way quinolone resistance is thought to develop. Our data warrant further in vivo investigations to determine the potential clinical relevance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Boyd LB, et al. 2008. Increased fluoroquinolone resistance with time in Escherichia coli from >17,000 patients at a large county hospital as a function of culture site, age, sex, and location. BMC Infect. Dis. 8:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Breines DM, et al. 1997. Quinolone resistance locus nfxD of Escherichia coli is a mutant allele of the parE gene encoding a subunit of topoisomerase IV. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:175–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cattaneo C, et al. 2008. Recent changes in bacterial epidemiology and the emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant Escherichia coli among patients with haematological malignancies: results of a prospective study on 823 patients at a single institution. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61:721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chang TM, et al. 2007. Characterization of fluoroquinolone resistance mechanisms and their correlation with the degree of resistance to clinically used fluoroquinolones among Escherichia coli isolates. J. Chemother. 19:488–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chien SC, et al. 1997. Pharmacokinetic profile of levofloxacin following once-daily 500-milligram oral or intravenous doses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2256–2260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2007. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 17th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S17 CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colombo AL, et al. 2009. Surveillance programs for detection and characterization of emergent pathogens and antimicrobial resistance: results from the Division of Infectious Diseases, UNIFESP. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 81:571–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Argenio DZ, Schumitzky A. 1997. ADAPT II user's guide: pharmacokinetic / pharmacodynamic systems analysis software. Biomedical simulations resource. University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunham SA, McPherson CJ, Miller AA. 2010. The relative contribution of efflux and target gene mutations to fluoroquinolone resistance in recent clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:279–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Everett MJ, Jin YF, Ricci V, Piddock LJ. 1996. Contributions of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2380–2386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fabrega A, Madurga S, Giralt E, Vila J. 2009. Mechanism of action of and resistance to quinolones. Microb. Biotechnol. 2:40–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fish DN, Chow AT. 1997. The clinical pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 32:101–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hawkey PM, Jones AM. 2009. The changing epidemiology of resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64(Suppl. 1):i3–i10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heisig P, Tschorny R. 1994. Characterization of fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli selected in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1284–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hooper DC. 2001. Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:337–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jumbe NL, et al. 2006. Quinolone efflux pumps play a central role in emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:310–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kiser TH, Obritsch MD, Jung R, MacLaren R, Fish DN. 2010. Efflux pump contribution to multidrug resistance in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pharmacotherapy 30:632–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Komp Lindgren P, Marcusson LL, Sandvang D, Frimodt-Moller N, Hughes D. 2005. Biological cost of single and multiple norfloxacin resistance mutations in Escherichia coli implicated in urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:2343–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kronvall G. 2010. Antimicrobial resistance 1979–2009 at Karolinska Hospital, Sweden: normalized resistance interpretation during a 30-year follow-up on Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli resistance development. APMIS 118:621–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee HH, Molla MN, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. 2010. Bacterial charity work leads to population-wide resistance. Nature 467:82–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lomovskaya O, et al. 1999. Use of a genetic approach to evaluate the consequences of inhibition of efflux pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1340–1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lomovskaya O, Watkins W. 2001. Inhibition of efflux pumps as a novel approach to combat drug resistance in bacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3:225–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Louie A, et al. 2007. In vitro infection model characterizing the effect of efflux pump inhibition on prevention of resistance to levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3988–4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma D, Alberti M, Lynch C, Nikaido H, Hearst JE. 1996. The local repressor AcrR plays a modulating role in the regulation of acrAB genes of Escherichia coli by global stress signals. Mol. Microbiol. 19:101–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marcusson LL, Frimodt-Moller N, Hughes D. 2009. Interplay in the selection of fluoroquinolone resistance and bacterial fitness. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mathai D, Jones RN, Pfaller MA, SENTRY Participant Group North America 2001. Epidemiology and frequency of resistance among pathogens causing urinary tract infections in 1,510 hospitalized patients: a report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (North America). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 40:129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morgan-Linnell SK, Becnel Boyd L, Steffen D, Zechiedrich L. 2009. Mechanisms accounting for fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:235–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morgan-Linnell SK, Zechiedrich L. 2007. Contributions of the combined effects of topoisomerase mutations toward fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:4205–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakamura S, Nakamura M, Kojima T, Yoshida H. 1989. gyrA and gyrB mutations in quinolone-resistant strains of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:254–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Piddock LJ. 2006. Clinically relevant chromosomally encoded multidrug resistance efflux pumps in bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:382–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Piddock LJ. 1999. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance: an update 1994–1998. Drugs 58(Suppl. 2):11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pumbwe L, Chang A, Smith RL, Wexler HM. 2006. Clinical significance of overexpression of multiple RND-family efflux pumps in Bacteroides fragilis isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ricci V, Tzakas P, Buckley A, Piddock LJ. 2006. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains are difficult to select in the absence of AcrB and TolC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:38–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saito R, et al. 2006. Role of type II topoisomerase mutations and AcrAB efflux pump in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Proteus mirabilis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:673–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singh R, et al. 2009. Pharmacodynamics of moxifloxacin against a high inoculum of Escherichia coli in an in vitro infection model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:556–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Swick MC, Morgan-Linnell SK, Carlson KM, Zechiedrich L. 2011. Expression of multidrug efflux pump genes acrAB-tolC, mdfA, and norE in Escherichia coli clinical isolates as a function of fluoroquinolone and multidrug resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:921–924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tam VH, et al. 2005. Bacterial-population responses to drug-selective pressure: examination of garenoxacin's effect on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 192:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tam VH, et al. 2007. Impact of drug-exposure intensity and duration of therapy on the emergence of Staphylococcus aureus resistance to a quinolone antimicrobial. J. Infect. Dis. 195:1818–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vila J, et al. 1994. Association between double mutation in gyrA gene of ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and MICs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2477–2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Webber MA, Piddock LJ. 2003. The importance of efflux pumps in bacterial antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:9–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang S, Clayton SR, Zechiedrich EL. 2003. Relative contributions of the AcrAB, MdfA and NorE efflux pumps to quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:545–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]