Abstract

The presence and characterization of plasmid-mediated fosfomycin resistance determinants among Escherichia coli isolates collected from pets in China between 2006 and 2010 were investigated. Twenty-nine isolates (9.0%) were positive for fosA3, and all of them were CTX-M producers. The fosA3 genes were flanked by IS26 and were localized on F2:A−:B− plasmids or on very similar F33:A−:B− plasmids carrying both blaCTX-M-65 and rmtB. These findings indicate that the fosA3 gene may be coselected by antimicrobials other than fosfomycin.

TEXT

Fosfomycin is a traditional antimicrobial agent with broad-spectrum bactericidal reactivity and good pharmacological properties. It used to be an alternative treatment for uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections which were caused by a wide variety of bacteria, including Escherichia coli (11, 19, 26). The recent growing prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lacta-mase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae and fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli has rekindled interest in fosfomycin as a therapeutic agent in many countries (7, 8, 18). Despite its worldwide use in clinical practice for nearly 4 decades, fosfomycin remains effective against common uropathogens without giving rise to clinically significant resistance (3, 6, 7, 9, 12, 15, 20). The main type of resistance to fosfomycin appears to be chromosome mediated rather than plasmid mediated (17, 21, 23, 27). However, two novel plasmid-mediated fosfomycin-modifying enzymes, FosA3 and FosC2, were recently identified in CTX-M-producing E. coli in Japan (25). Transferable plasmids carrying fosA3 or fosC2 might accelerate the dissemination of fosfomycin resistance around the world.

Fosfomycin has been approved for clinical application for many years in China. However, information on the occurrence and characteristics of fosfomycin-resistant E. coli in China is scarce. In the present study, we intended to examine the prevalence of fosfomycin resistance and plasmid-borne fosfomycin resistance genes among E. coli isolates from companion animals. A total of 323 E. coli isolates were recovered from healthy (136 isolates) and diseased (187 isolates) pets (248 from dogs and 75 from cats) at 10 pet hospitals in Guangdong Province, China, between 2006 and 2010.

The MICs of fosfomycin were determined by the agar dilution method on Mueller-Hinton agar containing 25 μg/ml glucose 6-phosphate, according to guideline M100-S20 of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (5). Most of the strains (89.9%) studied were susceptible to fosfomycin, whereas 33 isolates (10.2%) showed resistance to fosfomycin (MIC > 256 μg/ml). The 33 isolates were screened for the plasmid-borne fosfomycin resistance genes fosA3, fosC2, and fosA by PCR amplification and sequencing with the primers and PCR conditions listed in Table 1. Twenty-nine isolates (9.0%) were positive for fosA3 (Table 2). No fosC2 or fosA gene was detected among these isolates. Phylogenetic grouping of FosA3 producers as previously described (4) revealed that these E. coli isolates belonged to three phylogenetic groups (A, B1, and D) (Table 2). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (10) was successfully performed on 26 FosA3 producers, and 21 different XbaI PFGE patterns were observed. This suggested that the dissemination of fosA3 was not due to the clonal dissemination of fosA3-positive isolates. However, clonal expansion was observed between dogs and cats and between pet hospitals (Table 2). Moreover, three clonally related isolates (HN015, HN7A2, and HN109) which were grouped into phylogenetic group B1 were recovered from different animals and hospitals during 2008 and 2010 (Table 2). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis revealed that they all belonged to the same sequence type (clonal complex ST448) (data not shown).

Table 1.

Primers and PCR conditions used

| Primera | Sequence (5′–3′) | Size (bp) | Annealing temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FosA3-F | GCGTCAAGCCTGGCATTT | 282 | 57.5 |

| FosA3-R | GCCGTCAGGGTCGAGAAA | ||

| FosC2-F | TGGAGGCTACTTGGATTTG | 217 | 50.5 |

| FosC2-R | AGGCTACCGCTATGGATTT | ||

| IS26-F | GCACGCATCACCTCAATACC | Unknown | 56.7 |

| FosA3-R2 | TCATCCAGCGACAAGCACA | ||

| FosA3-F2 | GGGGCTGAGGTATGGAAAGA | Unknown | 56.1 |

| IS26-R | AGGAGATGCTGGCTGAACG | ||

| FosA-F | ATCTGTGGGTCTGCCTGTCGT | 271 | 59.5 |

| FosA-R | ATGCCCGCATAGGGCTTCT |

Primers were designed in this study.

Table 2.

Characterization of fosA3-carrying Escherichia coli isolates and plasmids

| Isolatea | Date (yr.mo) of isolation | Pet hospitalj | Originb | Resistance phenotypec | Resistance gene(s)d | Phylogenetic group | PFGE typee | Plasmid |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (bp) downstream of fosA3f | FAB formulag | EcoRI RFLPh | Addiction system(s) | ||||||||

| HN4E2 | 2008.5 | PH1 | Dog pharynx | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 1a | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN429 | 2008.4 | PH2 | Cat feces* | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 1b | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN2F2 | 2008.5 | PH1 | Cat feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | B1 | 2 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN7A8 | 2008.1 | PH3 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, blaCTX-M-55, rmtB | B1 | 2 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN2B1 | 2007.12 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | D | 3 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN3D12 | 2008.4 | PH3 | Cat feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 4 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC, ccdAB |

| HN4B5 | 2008.1 | PH3 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | NT | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC, ccdAB |

| HN5E3 | 2008.4 | PH1 | Dog pus | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 5 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ib | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN4A1 | 2008.1 | PH3 | Dog feces* | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 6 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN127 | 2010.4 | PH4 | Dog feces* | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | D | NT | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN053 | 2009.7 | PH1 | Dog feces* | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 7 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ia | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN131 | 2010.5 | PH4 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 8 | 536 | F33:A−:B− | Ic | pemKI, hok-sok, srnBC |

| HN212 | 2010.1 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-65,rmtB | A | 9 | 1,758 | F33:A−:B− | VI | pemKI, srnBC |

| HN1E1 | 2009.5 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | B1 | 10 | 1,758 | F2:A−:B− | IVc | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN015 | 2008.1 | PH4 | Cat feces* | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-3, rmtB | B1 | 11 | 1,758 | F2:A−:B− | NDi | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN7A2 | 2008.1 | PH4 | Dog sneeze | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-3, rmtB | B1 | 11 | 1,758 | F2:A−:B− | IVa | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN109 | 2010.5 | PH3 | Cat feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-3, rmtB | B1 | 11 | 1,758 | F2:A−:B− | ND | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HNC50 | 2006.12 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-3,blaCTX-M-65, armA | D | NT | 1,758 | F2:A−:B− | ND | pemKI |

| HNC1 | 2006.9 | PH1 | Cat feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-3, rmtB | A | 12 | 536 | Unknown | V | pemKI |

| HN225 | 2010.2 | PH1 | Cat feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-27, rmtB | D | 13 | 1,758 | Unknown | ND | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN357 | 2010.4 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-27, rmtB | D | 13 | 1,758 | ND | ND | ND |

| HN1D5 | 2008.2 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65, rmtB | A | 14 | 536 | F2:A−:B− | IIa | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN2E7 | 2008.5 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65,rmtB | A | 15 | 536 | F2:A−:B− | IVb | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN3C6 | 2008.3 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, TET | blaCTX-M-14, rmtB | D | 16 | 536 | F2:A−:B− | IIb | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN5A12 | 2008.3 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-27, armA | D | 17 | 536 | Unknown | IIIa | pemKI |

| HN061 | 2009.7 | PH5 | Dog feces | CTX, AMI, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-14, rmtB | D | 18 | 536 | ND | ND | ND |

| HN3B9 | 2009.4 | PH1 | Dog feces | CTX, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-65 | A | 19 | 370 | F2:A−:B− | IIIb | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN3E7 | 2008.2 | PH4 | Cat feces* | CTX, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-3 | D | 20 | 370 | F2:A−:B− | IVb | pemKI, hok-sok |

| HN4F8 | 2008.4 | PH3 | Dog feces | CTX, CIP, CHL, TET | blaCTX-M-14 | A | 21 | 370 | Unknown | ND | None |

Isolates from which the fosA3 gene was transferred to the recipient by conjugation or transformation (isolates HN7A8, HN3D12, HN109, and HN225) are underlined.

Healthy pets are indicated by asterisks.

All isolates and all transconjugants and transformants were resistant to fosfomycin. Resistance phenotypes transferred to the recipient by conjugation are underlined. CTX, cefotaxime; AMK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CHL, chloramphenicol; TET, tetracycline.

Genes that were transferred by conjugation or transformation, as determined by PCR, are underlined.

PFGE types (1, 2, 3, etc.) were assigned by visual inspection of the macrorestriction profile. Patterns that differed by fewer than six bands were considered to represent subtypes within the main group (1a, 1b, etc.). NT, nontypeable.

The size of the spacer region between the 3′ end of fosA3 and IS26.

Allele numbers were assigned by submitting the amplicon sequence to the Multilocus Sequence Typing database (www.pubmlst.org/plasmid).

RFLP patterns that differed by only a few bands (1 to 3) were assigned to the same RFLP profile.

ND, not determined.

PH1 to PH5, pet hospitals 1 to 5, respectively.

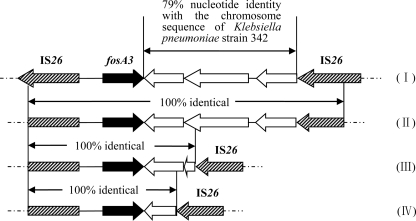

MICs of cefotaxime, amikacin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and ciprofloxacin were determined by the agar dilution method, and the results were interpreted according to the CLSI breakpoints (5). It revealed that all fosA3-positive isolates were resistant or intermediate to cefotaxime, while 26 and 27 isolates showed resistance to amikacin and ciprofloxacin, respectively. The occurrence of rmtB, armA, and blaCTX-M among these fosA3-positive isolates was determined by PCR amplification and sequencing as previously described (2, 22). All of the fosA3-positive isolates were CTX-M producers, and 16 of them produced CTX-M-65 (Table 2). In addition, 24 and 2 of them carried rmtB and armA, respectively. Details for all fosA3-positive isolates are shown in Table 2. Specific primers were designed according to reported surrounding structures to determine the genetic environment of the fosA3 gene (Table 1). The results showed that all fosA3 genes were flanked by IS26, which was similar to the genetic environment of the first-reported fosA3 gene (25). All fosA3 genes were located 316 bp downstream of IS26. However, the size of the spacer region between the 3′ end of fosA3 and IS26 varied (536, 1,758, and 370 bp) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Moreover, the 1,758-bp region had 79% nucleotide identity with a part of the chromosome sequence of Klebsiella pneumoniae strain 342 and was 100% identical to the sequence downstream of fosA3 in E. coli 08-642, an isolate from Japan (Fig. 1) (25).

Fig 1.

Comparison of regions flanking fosA3. (I)Escherichia coli 08-642 from Japan (23). (II) The size of the spacer region between the 3′ end of fosA3 and IS26 is 1,758 bp (GenBank accession no. JF411006). (III) The size of the spacer region between the 3′ end of fosA3 and IS26 is 536 bp (GenBank accession no. JF411007). (IV) The size of the spacer region between the 3′ end of fosA3 and IS26 is 370 bp (GenBank accession no. JF411008).

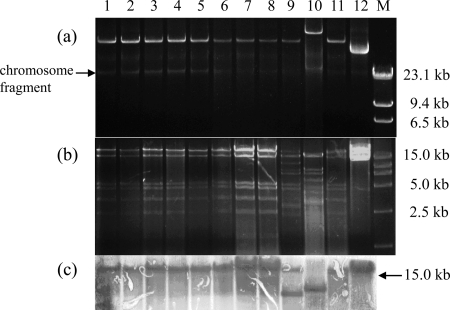

Conjugation was carried out to determine the transferability of fosA3 genes with E. coli C600 (high level resistance to streptomycin) as the recipient (2). Transconjugants were selected on MacConkey agar plates containing fosfomycin (100 μg/ml) and streptomycin (2,000 μg/ml) for counterselection. When plasmid cotransfer occurred, a transformation experiment was carried out. Transformants were selected in LB agar plates containing 200 μg/ml fosfomycin by using E. coli DH5α as the recipient. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was conducted for transconjugants and transformants, and the transfer of the resistance gene was confirmed by PCR as described above. The fosA3 genes were successfully transferred to the recipients from 27 donors by conjugation or transformation (Table 2). The 23 transconjugants and 4 transformants all showed extraordinarily high-level resistance to fosfomycin (Table 2). In addition, blaCTX-M and rmtB genes were cotransferred to the recipients with fosA3 from 25 and 18 donors, respectively. Plasmids were assigned to incompatibility groups by PCR-based replicon typing (1). Replicon sequence typing was used to characterize the IncFII plasmids (24). F33:A−:B− and F2:A−:B− were identified in 13 and 10 plasmids carrying fosA3, respectively. F33:A−:B− plasmids also contained blaCTX-M-65 and rmtB and had nearly identical sizes and EcoRI digestion profiles (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Southern blot hybridization was performed on EcoRI digestion fragments of 12 F33:A−:B− plasmids with a digoxigenin-labeled probe specific for fosA3. It showed that fosA3 was located on the same-size band (>15 kb, the largest digestion fragment) in 9 isolates (Fig. 2), demonstrating the presence of an epidemic plasmid responsible for the dissemination of fosA3. However, the predominance of the F33:A−:B− plasmid type was unexpected, since the pets were epidemiologically unrelated and samples had been obtained in different periods at four different hospitals between 2007 and 2010. To better understand the successful dissemination of these IncFII plasmids carrying fosA3, plasmid addiction systems were determined using primers described by Mnif et al. (16). pemKI (n = 26), hok-sok (n = 22), and srnBC (n = 13) were the most frequently represented systems, and almost all F33:A−:B− plasmids carried these three addiction systems (Table 2).

Fig 2.

Analysis of F33:A−:B− plasmids carrying fosA3. Lanes 1 to 12, HN429, HN7A8, HN2B1, HN3D12, HN4B5, HN4A1, HN127, HN053, HN5E3, HN212, HN4E2, and HN131; lane M, λHindIII and DL15000 marker. (a) Plasmid profiles of transconjugants and transformants carrying F33:A−:B− plasmid. (b) EcoRI restriction digestion profiles of F33:A−:B− plasmids. (c) Southern blot hybridization of EcoRI-digested plasmids with a digoxigenin-labeled fosA3-specific probe.

The occurrence of fosfomycin resistance in E. coli from human and pet animal isolates is still rare in many countries (<5%) (3, 6, 7, 9, 12, 13, 15, 20). However, in this study, a higher prevalence of fosfomycin resistance mainly mediated by FosA3 was observed in E. coli isolates recovered from pets during 2006 and 2010, although none of the pets had received fosfomycin treatment. The association with other resistance determinants has likely favored the dissemination and maintenance of fosA3, since the additional resistance genes, such as blaCTX-M and rmtB, allow coselection of fosA3 by cephalosporins and/or aminoglycosides (especially amikacin and gentamicin), which have been frequently used for pet therapy in China (14).

In conclusion, the dissemination of the fosA3 gene, which is closely associated with blaCTX-M and rmtB, is mainly driven by horizontal transfer of F33:A−:B− and F2:A−:B− plasmids rather than clonal expansion. Since pets are able to acquire multidrug-resistant pathogens and transmit them to humans due to their close contact, the presence of these resistance bacteria and plasmids in pets may become a public health concern. Effective antimicrobial policies in veterinary hospitals should be developed in China.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers JF411006, JF411007, and JF411008.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jun-ichi Wachino for providing the sequence flanking fosA3 for comparison. We thank Minggui Wang for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by grants 30972218 and U1031004 from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 9 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Carattoli A, et al. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J. Microbiol. Methods 63:219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen L, et al. 2007. Emergence of RmtB methylase-producing Escherichia coli and Enterobacter cloacae isolates from pigs in China. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59:880–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chislett RJ, White G, Hills T, Turner DP. 2010. Fosfomycin susceptibility among extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Nottingham, UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1076–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555–4558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2010. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: twentieth informational supplement, M100-S20. CLSI, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 6. Endimiani A, et al. 2010. In vitro activity of fosfomycin against blaKPC-containing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, including those nonsusceptible to tigecycline and/or colistin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:526–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Falagas ME, Kastoris AC, Kapaskelis AM, Karageorgopoulos DE. 2010. Fosfomycin for the treatment of multidrug-resistant, including extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing, Enterobacteriaceae infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 10:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Falagas ME, Giannopoulou KP, Kokolakis GN, Rafailidis PI. 2008. Fosfomycin: use beyond urinary tract and gastrointestinal infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Falagas ME, et al. 2010. Antimicrobial susceptibility of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Enterobacteriaceae isolates to fosfomycin. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:240–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gautom RK. 1997. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2977–2980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta K, et al. 2011. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:e103–e120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsu MS, et al. 2011. In vitro susceptibilities of clinical isolates of ertapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae to nemonoxacin, tigecycline, fosfomycin and other antimicrobial agents. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 37:276–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hubka P, Boothe DM. 2011. In vitro susceptibility of canine and feline Escherichia coli to fosfomycin. Vet. Microbiol. 149:277–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lei T, et al. 2010. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from food animals, animal food products and companion animals in China. Vet. Microbiol. 146:85–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maraki S, et al. 2009. Susceptibility of urinary tract bacteria to fosfomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4508–4510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mnif B, et al. 2010. Molecular characterization of addiction systems of plasmids encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:1599–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oteo J, et al. 2009. CTX-M-15-producing urinary Escherichia coli O25b-ST131-phylogroup B2 has acquired resistance to fosfomycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:712–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oteo J, Pérez-Vázquez M, Campos J. 2010. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Escherichia coli: changing epidemiology and clinical impact. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23:320–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patel SS, Balfour JA, Bryson HM. 1997. Fosfomycin tromethamine. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy as a single-dose oral treatment for acute uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections. Drugs 53:637–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Samonis G, et al. 2010. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-negative nonurinary bacteria to fosfomycin and other antimicrobials. Future Microbiol. 5:961–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seoane A, Sangari FJ, Lobo JM. 2010. Complete nucleotide sequence of the fosfomycin resistance transposon Tn2921. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:413–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun Y, et al. 2010. High prevalence of blaCTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamase genes in Escherichia coli isolates from pets and emergence of CTX-M-64 in China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1475–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takahata S, et al. 2010. Molecular mechanisms of fosfomycin resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 35:333–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Villa L, GarcíA-Fernández A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. 2010. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2518–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wachino J, Yamane K, Suzuki S, Kimura K, Arakawa Y. 2010. Prevalence of fosfomycin resistance among CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli clinical isolates in Japan and identification of novel plasmid-mediated fosfomycin-modifying enzymes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:3061–3064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Warren JW, et al. 1999. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:745–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xu H, Miao V, Kwong W, Xia R, Davies J. 2011. Identification of a novel fosfomycin resistance gene (fosA2) in Enterobacter cloacae from the Salmon River, Canada. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 52:427–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]