Abstract

As major causes of hospital-acquired infections, antibiotic-resistant enterococci are a serious public health concern. Enterococci are intrinsically resistant to many cephalosporin antibiotics, a trait that enables proliferation in patients undergoing cephalosporin therapy. Although a few genetic determinants of cephalosporin resistance in enterococci have been described, overall, many questions remain about the underlying genetic and biochemical basis for cephalosporin resistance. Here we describe an unexpected effect of specific mutations in the β subunit of RNA polymerase (RNAP) on intrinsic cephalosporin resistance in enterococci. We found that RNAP mutants, selected initially on the basis of their ability to provide resistance to rifampin, resulted in allele-specific alterations of the intrinsic resistance of enterococci toward expanded- and broad-spectrum cephalosporins. These mutations did not affect resistance toward a diverse collection of other antibiotics that target a range of alternative cellular processes. We propose that the RNAP mutations identified here lead to alterations in transcription of as-yet-unknown genes that are critical for cellular adaption to cephalosporin stress.

INTRODUCTION

As major causes of hospital-acquired infections, antibiotic-resistant enterococci are a serious public health concern (14). Enterococci normally inhabit the gastrointestinal tract of many insects and animals, including humans (1, 34). They are adept at sharing mobile genetic elements carrying antibiotic resistance determinants, contributing to the emergence of multiresistant clones in the hospital setting (13). In addition, enterococci are intrinsically resistant to broad-spectrum cephalosporins (27), antibiotics that belong to the β-lactam family and interfere with cell wall (peptidoglycan) biosynthesis by inhibiting the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) that cross-link peptidoglycan (35, 38). Enterococci proliferate and achieve an abnormally high population size in patients undergoing cephalosporin therapy (8), presumably due to this cephalosporin resistance trait. This population bloom likely contributes to the emergence of enterococcal infections by facilitating dissemination of the bacteria to other sites. Intrinsic cephalosporin resistance is a trait exhibited by enterococci belonging to both of the species that account for nearly all hospital-acquired enterococcal infections, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium.

Despite the importance of intrinsic cephalosporin resistance, only a few genetic determinants specifying resistance in enterococci have been described. These include the following: (i) pbp5, which encodes a so-called “low-affinity” penicillin-binding protein that is thought to mediate peptidoglycan cross-linking in the presence of cephalosporins due to its reduced affinity for the drugs (4, 33); (ii) ireK (formerly prkC), which encodes a transmembrane Ser/Thr kinase whose kinase activity is critical for cephalosporin resistance (19, 21), although its targets remain unknown; and (iii) a locus encoding a two-component signal transduction system (CroRS), mutations in which render E. faecalis markedly susceptible to cephalosporins (6, 12). The response regulator component of the CroRS signaling system (CroR) contains a functional DNA-binding domain, suggesting that transcriptional remodeling is necessary for adaptation to the stress imposed by cephalosporins. However, thus far, only a few genes controlled directly by CroR have been identified. These include salB, encoding a secreted protein that does not contribute to cephalosporin resistance (26), croRS itself (26), and a locus of genes encoding a putative glutamine transporter (22) with no obvious connection to cephalosporin resistance.

Here we describe an unexpected effect of specific mutations in the β subunit of RNA polymerase (RNAP) on intrinsic cephalosporin resistance in enterococci. We found that RNAP mutants, selected initially on the basis of their ability to provide resistance to the antibiotic rifampin (Rifr mutants), resulted in allele-specific alterations of the intrinsic resistance of enterococci toward expanded- and broad-spectrum cephalosporins. This effect was observed in divergent genetic lineages of E. faecalis. Similarly, a specific mutation in RNAP from 2 lineages of E. faecium led to enhanced cephalosporin resistance. In contrast, these RNAP mutations did not affect resistance toward a diverse collection of other antibiotics that target a range of alternative cellular processes. We propose that the RNAP mutations identified here lead to alterations in transcription of as-yet-unknown genes that are critical for cellular adaption to cephalosporin stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth media, and chemicals.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Brain heart infusion medium (BHI) and Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) were prepared as described by the manufacturer (Becton Dickinson). Bacteria were stored at −80°C in BHI supplemented with 30% glycerol. Antibiotics and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise indicated. Erythromycin (Em) was used at 10 μg/ml for growth of resistant E. faecalis.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. faecalis | ||

| OG1 | Wild-type, original unmarked isolate (MLST 1) | 11 |

| CK135 | OG1 rpoB H486Y (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| JL206 | OG1 ΔireK2 | This work |

| JL339 | OG1 Δpbp5-2 | This work |

| JL209 | OG1 rpoB H486Y (spontaneous Rifr derivative, independent isolate) | This work |

| JL213 | OG1 rpoB H486D (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| JL211 | OG1 rpoB Q473K (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| JL308 | OG1 rpoB H486Y Δpbp5-2 | This work |

| JL235 | OG1 rpoB H486Y ΔireK2 (spontaneous Rifr derivative of JL206) | This work |

| T1 (SS498) | Wild-type (MLST 21), CDC reference strain | 23 |

| JL220 | T1 rpoB H486Y (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| JL219 | T1 rpoB H486D (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| JL224 | T1 rpoB Q473K (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| E. faecium | ||

| Com12 | Fecal isolate | 25 |

| JL282 | Com12 rpoB H486Y (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| 1,231,501 | Clinical isolate | 30 |

| JL277 | 1,231,501 rpoB H486Y (spontaneous Rifr derivative) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pJRG8 | E. faecalis expression vector, constitutive P23 promoter (Emr) | 19 |

| pJLL52 | rpoB H486Y cloned into pJRG8 | This work |

| pJLL50 | rpoB H486D cloned into pJRG8 | This work |

| pJLL21 | Δpbp5-2 allele in the allelic exchange vector pJRG32 | 35a |

| pCJK74 | ΔireK2 allele in the allelic exchange vector pCJK47 | 21 |

MLST, multilocus sequence type.

Isolation and sequencing of enterococcal Rifr mutants.

The MIC of E. faecalis OG1 for rifampin (Rif) under our conditions (see below) was determined to be 8 μg/ml. To isolate Rifr mutants, independent cultures inoculated from isolated colonies on BHI agar plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in BHI with agitation. Bacteria were concentrated approximately 20-fold by centrifugation and resuspension in BHI, followed by plating on BHI agar supplemented with rifampin at 200 μg/ml and incubation at 37°C. Rifr colonies typically appeared within ∼24 h. Colonies that arose were streaked for purification on BHI agar and retested to ensure they retained the Rifr phenotype. To identify the mutation responsible for resistance to Rif, a segment of the rpoB gene that included Rif clusters I to III was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of the Rifr mutants and the amplicon was subjected to DNA sequencing. The numbering scheme of Ozawa and coworkers (29) for E. faecalis RpoB was used to designate amino acids that had undergone substitutions in the mutants.

Construction of E. faecalis rpoB H486Y mutants lacking ireK or pbp5.

Unmarked, in-frame deletions of the genes encoding IreK or Pbp5 were constructed as previously described (21, 35a) using the markerless exchange system described by Kristich et al. (18). Briefly, an allelic exchange plasmid carrying the desired deletion allele (pJLL21 or pCJK74) was transferred to the corresponding native location in the E. faecalis chromosome using pVE6007 as a helper plasmid to facilitate recombination via published methods (20). Successful isolation of deletion mutants was achieved by plating on counterselection plates and incubating at 30°C for ∼2 to 3 days. A mutant (the JL308 strain) carrying the rpoB H486Y allele in combination with the pbp5 deletion was constructed by allelic exchange with pJLL21 in the CK135 strain. A mutant (the JL235 strain) carrying the rpoB H486Y allele in combination with the ireK deletion was constructed by selecting spontaneous Rifr mutants in the ΔireK mutant (JL206) background and then sequencing rpoB to verify the allele.

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmids to express alleles of rpoB in E. faecalis were constructed by amplifying the full-length rpoB open reading frame (ORF) from the genomic DNA of the appropriate strain (CK135 or JL213) and cloning the amplicons with primer-specified restriction sites into SpeI/XhoI-digested pJRG8, an E. faecalis expression vector, creating pJLL52 and pJLL50, respectively. Because E. faecalis rpoB contains an internal SpeI restriction site, we used the enzyme BsaI to generate SpeI-compatible ends on the rpoB PCR amplicons for cloning.

Tests of antibiotic sensitivity.

MICs for antibiotics were determined in aerobic liquid cultures using a microtiter plate serial dilution method in a Bioscreen C plate reader (Oy Growth Curves Ab, Ltd.). Two-fold dilutions of antibiotics in MHB were prepared in the wells of a 100-well honeycomb microtiter plate. Bacteria from stationary-phase cultures in MHB were inoculated into each well at a density of ∼105 CFU/ml. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, with brief shaking and measurement of the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) at 15-min intervals. The lowest concentration of antibiotic that prevented growth was recorded as the MIC. In some cases, antibiotic susceptibility was also assessed by preparing serial 10-fold dilutions of stationary-phase cultures and inoculating aliquots onto the surface of agar plates supplemented with antibiotics.

RESULTS

We initially sought to generate a derivative of wild-type E. faecalis OG1 that was marked with a stable genetic lesion conferring an antibiotic resistance phenotype. One such phenotype that has historically been used to mark susceptible strains of E. faecalis is resistance to the antibiotic rifampin (5, 9), which binds to bacterial RNA polymerase and prevents initiation of transcription (37). Spontaneous Rifr mutants can readily be obtained by plating a population of bacteria in the presence of inhibitory concentrations of Rif. Previous studies of numerous species of bacteria established that such Rifr mutants carry missense mutations in specific segments of the β subunit of RNA polymerase (encoded by the rpoB gene), the most common of which is known as “Rif cluster I” (3, 10, 16, 17, 24, 28, 36). These mutations cluster in or near the Rif-binding site on RNAP and prevent Rif from binding efficiently (reviewed in reference 10).

Rifr mutants of E. faecalis exhibit altered resistance to cephalosporins.

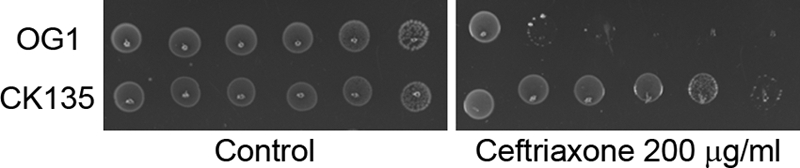

After obtaining a spontaneous Rifr mutant of E. faecalis OG1 (strain CK135) on selection plates containing 200 μg/ml rifampin, we serendipitously observed that the mutant exhibited enhanced resistance to ceftriaxone (a broad-spectrum cephalosporin antibiotic) relative to that of its otherwise isogenic parent (Fig. 1 and Table 2). To explore this observation in more detail, we isolated additional spontaneous Rifr mutants from multiple independent cultures of E. faecalis OG1. Rifr mutants arose at a frequency of ∼10−8 per viable CFU, comparable to that of previously reported selections in E. coli (17). The mutations responsible for resistance to Rif were identified by sequencing the region of E. faecalis rpoB corresponding to Rif clusters I to III of E. coli rpoB. All E. faecalis Rifr mutants we isolated carried missense mutations in Rif cluster I. Three rpoB alleles were identified, all of which have been reported to confer Rifr in other bacterial species: rpoB H486Y (isolated in multiple independent mutants), rpoB H486D, and rpoB Q473K. To determine if these mutations conferred substantial defects in fitness, we measured generation times for exponentially growing cells, including two independently derived rpoB H486Y mutants. Mutants with substitutions at H486 exhibited growth rates similar to those of the wild type (generation times of 69 ± 4 min for wild-type OG1, 74 ± 4 min for rpoB H486Y, and 70 ± 4 min for rpoB H486D). Only the rpoB Q473K mutation had an obvious effect on growth rate, leading to a minor increase in generation time (generation time of 79 ± 4 min). A similar trend was previously reported for an analogous set of RpoB mutants in Bacillus subtilis (24).

Fig 1.

An E. faecalis Rifr mutant carrying rpoB H486Y exhibits enhanced resistance to ceftriaxone. Cultures were subjected to 10-fold serial dilutions and inoculated (left to right, least to most dilute) on MHB agar supplemented with ceftriaxone. The strains used were OG1, the wild-type E. faecalis strain, and CK135, OG1 carrying the rpoB H486Y allele. Results are representative of a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

Table 2.

Median MICs for E. faecalis OG1 and its derivativesa

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) of each E. faecalis strain (rpoB allele) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OG1 (wild type) | CK135 (H486Y) | JL209 (H486Y) | JL213 (H486D) | JL211 (Q473K) | |

| Cephalosporins | |||||

| Ceftriaxone (broad spectrum) | 64 | 512 | 1,024 | 16 | 8 |

| Ceftazidime (broad spectrum) | 512 | 2,048 | 2,048 | 128 | 32 |

| Cefuroxime (expanded spectrum) | 64 | 512 | 512 | 16 | 8 |

| Cefadroxil (narrow spectrum) | 64 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 64 |

| Others that target cell wall synthesis | |||||

| Ampicillin | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Vancomycin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Bacitracin | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 |

| d-Cycloserine | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 | 128 |

| Others that do not target cell wall synthesis | |||||

| Chloramphenicol | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Kanamycin | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 32 |

| Norfloxacin | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

MICs were determined in MHB after 24 h at 37°C from a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

In light of the initial observation that the Rifr strain CK135 exhibited enhanced cephalosporin resistance, we measured the relative susceptibilities (MICs) of the Rifr mutants toward a panel of antibiotics that target a spectrum of diverse cellular processes (Table 2). We found that susceptibility to expanded-spectrum (cefuroxime) and broad-spectrum (ceftriaxone and ceftazidime) cephalosporins was substantially altered in an allele-specific manner. Both rpoB H486Y mutants exhibited markedly enhanced resistance to these drugs, whereas a mutant carrying a different substitution at the same site (rpoB H486D) or a substitution at a nearby site (rpoB Q473K) exhibited reduced resistance to the expanded- and broad-spectrum and cephalosporins. Changes in susceptibility to a narrow-spectrum cephalosporin (cefadroxil) and to the other β-lactam antibiotic tested (ampicillin) followed a similar trend in most cases but were modest in magnitude (2-fold), and 2-fold changes in MICs determined via the broth microdilution method are typically not considered reliable. In contrast to the susceptibility changes described above, none of the Rifr mutants exhibited differences in susceptibility toward antibiotics that target other aspects of cell wall biosynthesis (vancomycin, bacitracin, D-cycloserine) or toward antibiotics with non-cell-wall targets (chloramphenicol, kanamycin, norfloxacin). Thus, specific alleles of rpoB exert unique effects on susceptibility of E. faecalis to expanded- and broad-spectrum cephalosporins.

To determine if this phenomenon was unique to the OG1 genetic background, we isolated spontaneous Rifr mutants in a divergent lineage of E. faecalis (T1). Spontaneous E. faecalis T1 Rifr derivatives containing equivalent sets of rpoB alleles were obtained from multiple independent cultures and verified by sequencing of Rif cluster I of rpoB. Susceptibility tests of the T1 mutants revealed that, as was observed in the OG1 genetic background, the rpoB H486Y mutant exhibited markedly enhanced resistance to cephalosporins (Table 3). No change in susceptibility toward norfloxacin was observed for any of the mutants, confirming the specificity of the effect for cephalosporins. In contrast to what was observed in the OG1 genetic background, the rpoB H486D and rpoB Q473K mutants did not exhibit a reduction in cephalosporin resistance in the E. faecalis T1 genetic background. The reasons for this difference remain unclear.

Table 3.

Median MICs for enterococci of other genetic lineagesa

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) of each strain and rpoB alleleb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. faecalis T1 |

E. faecium Com12 |

E. faecium 1,231,501 |

||||||

| WT | H486Y | H486D | Q473K | WT | H486Y | WT | H486Y | |

| Ceftriaxone | 16 | 128 | 16 | 16 | 128 | 1,024 | 256 | 1,024 |

| Ceftazidime | 64 | 512 | 128 | 32 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Norfloxacin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

MICs were determined in MHB after 24 h at 37°C from a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

WT, wild-type rpoB allele (H486) (for all 3 strains); ND, not determined.

Genetic linkage of rpoB H486Y with enhanced cephalosporin resistance.

The observation that multiple independently isolated, single-step rpoB H486Y mutations in divergent genetic lineages all conferred enhanced cephalosporin resistance to E. faecalis was a strong indication that the H486Y substitution was indeed responsible for this phenotype. To formally exclude the possibility that a (unknown) secondary mutation(s) elsewhere in the genome was responsible for enhanced cephalosporin resistance of the rpoB mutants, we tested for linkage between the rpoB H486Y allele and the enhanced cephalosporin resistance phenotype. Unfortunately, genetic tools that would enable efficient backcrossing of the rpoB mutations to a clean genetic background are not available for E. faecalis. Technical challenges associated with using available allelic exchange methods to introduce mutations into the large and essential rpoB gene de novo prompted us to address this question by simply cloning the rpoB genes from selected rpoB mutants into an E. faecalis expression vector. Recombinant expression vectors carrying either rpoB H486Y (from the CK135 strain) or rpoB H486D (from the JL213 strain) were introduced into the Rif-susceptible (Rifs) parental strain (OG1) to create merodiploid strains carrying both wild-type (chromosomal) and mutant copies of rpoB. Susceptibility analyses of the resulting strains revealed that, as expected, expression of both the rpoB H486Y and rpoB H486D alleles conferred rifampin resistance (Table 4). While both plasmid-borne rpoB alleles conferred resistance to rifampin, expression of the rpoB H486Y allele enhanced cephalosporin resistance of the parental strain whereas expression of the rpoB H486D allele did not (Table 4), confirming that rpoB H486Y is indeed responsible for enhanced cephalosporin resistance in the original spontaneous Rifr mutants.

Table 4.

Median MICs for E. faecalis OG1 strain with plasmid-borne rpoB allelesa

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) of each plasmid-carrying OG1 strain (rpoB allele carried on plasmid) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OG1(pJRG8) (empty vector) | OG1(pJLL52) (H486Y) | OG1(pJLL50) (H486D) | |

| Rifampin | 8 | >256 | >256 |

| Ceftriaxone | 64 | 256 | 64 |

| Ceftazidime | 256 | 1,024 | 256 |

| Cefuroxime | 128 | 256 | 128 |

| Cefadroxil | 64 | 64 | 64 |

MICs were determined in MHB supplemented with Em after 24 h at 37°C from a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

RNA polymerase mutations do not bypass IreK or Pbp5.

Previous studies established that deletions of the genes encoding the Ser/Thr kinase IreK or the penicillin-binding protein Pbp5 render E. faecalis markedly susceptible to cephalosporins (2, 21). To probe the relationship of rpoB H486Y-mediated cephalosporin resistance to these previously described resistance determinants, we sought to determine if rpoB H486Y-mediated enhanced cephalosporin resistance could overcome the effect of these deletions. To do so, we performed epistasis experiments by constructing strains carrying the rpoB H486Y allele in combination with a deletion in either ireK or pbp5. Susceptibility tests on the resulting strains revealed that both deletions eliminated the hyperresistant phenotype conferred by rpoB H486Y and rendered E. faecalis susceptible to ceftriaxone. In side-by-side experiments, ceftriaxone MICs were determined to be 1 μg/ml for pbp5 deletion mutants that were either Rifs (the JL339 strain) or Rifr (due to rpoB H486Y [the JL308 strain]). Similarly, ceftriaxone MICs were determined to be 4 μg/ml for the Rifs ireK deletion mutant (the JL206 strain) and 8 μg/ml for the Rifr rpoB H486Y ireK deletion mutant (the JL235 strain), indicating that rpoB H486Y cannot bypass the requirements for IreK or Pbp5 to confer high-level intrinsic cephalosporin resistance in E. faecalis.

Rifr mutations in E. faecium enhance cephalosporin resistance.

Given that we observed rpoB H486Y-mediated enhancement of cephalosporin resistance in divergent genetic lineages of E. faecalis, we asked if a similar phenomenon could also be observed in other enterococcal species. To test this, we selected spontaneous Rifr mutants derived from two independent lineages of E. faecium (E. faecium Com12 and 1,231,501), an enterococcal species that also exhibits Pbp5-dependent intrinsic resistance to cephalosporins (4). Targeted sequencing of the E. faecium rpoB Rif regions from a collection of Rifr mutants revealed isolates containing rpoB H486Y alleles, which were subjected to cephalosporin susceptibility tests. The results revealed that rpoB H486Y mutants from both E. faecium lineages exhibit enhanced resistance to ceftriaxone (Table 3), indicating that this phenomenon is not restricted to the species E. faecalis.

DISCUSSION

This work describes an unexpected effect of specific mutations in the β subunit of RNAP on intrinsic cephalosporin resistance in enterococci. The principal findings of this study can be summarized as follows.

(i) Spontaneous Rifr mutants derived from two divergent lineages of E. faecalis were obtained. Each of the mutants carried a mutation in rpoB, encoding the β subunit of RNAP, and each mutation we obtained corresponds to an rpoB allele that is known to confer resistance to rifampin in other species of bacteria. We confirmed that two such alleles of E. faecalis rpoB (rpoB H486Y and rpoB H486D) are indeed responsible for resistance to Rif by expressing them in an otherwise susceptible E. faecalis strain (Table 4). Although our selections yielded mutants with two different substitutions at H486 of RpoB, we did not obtain the rpoB H486R allele that is responsible for Rifr in the widely used laboratory strain of E. faecalis, OG1RF (29). The reasons for this are unknown but may be related to the specific environmental conditions used in our Rifr selections. Previous studies in Bacillus subtilis have established that environmental conditions can influence the spectrum of Rifr mutations obtained in a given selection (28).

(ii) The Rifr mutations in rpoB altered enterococcal intrinsic resistance to cephalosporins in an allele-specific manner (Tables 2 and 3). In particular, the rpoB H486Y allele markedly enhanced resistance to expanded- and broad-spectrum cephalosporins, while other Rifr alleles—including a different substitution at the same site in rpoB (rpoB H486D)—either conferred a reduced level of resistance (in the OG1 genetic background) or did not substantially affect resistance (in the T1 genetic background). In addition, the rpoB H486Y mutations conferred enhanced resistance to cephalosporins not only in two lineages of E. faecalis but also in two lineages of a distinct species of enterococci, E. faecium. Thus, it seems likely that the underlying mechanism leading to enhanced cephalosporin resistance in strains carrying the rpoB H486Y allele is widely conserved among enterococci.

(iii) The effects of rpoB alleles on resistance were specific to expanded- and broad-spectrum cephalosporins (Tables 2 and 3). Little to no effects of the rpoB mutations were observed for other antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis or for antibiotics with targets unrelated to cell wall synthesis, strongly suggesting that enhanced cephalosporin resistance observed with rpoB H486Y is not the result of a nonspecific general change in integrity of the cell wall or an enhanced general stress response but rather an alteration in a specific cellular process that promotes resistance to cephalosporins.

(iv) The rpoB H486Y allele cannot confer high-level cephalosporin resistance to E. faecalis in the absence of either IreK kinase or Pbp5. This observation is perhaps unsurprising in the case of Pbp5, as Pbp5 is thought to perform the critical final peptidoglycan cross-linking step during cell wall synthesis in the presence of cephalosporins. For IreK, interpretation of this result is more complicated, as the signaling network controlled by IreK has not yet been defined.

Rifr alleles of RNAP confer a variety of phenotypic effects in other bacteria. In B. subtilis, extensive analysis of the effects of a variety of Rifr mutations in rpoB revealed allele-specific differences in genetic competence (24), sporulation (24), and carbohydrate utilization (32). It seems likely that global aberrations in coordinated transcriptional remodeling due to Rifr mutant polymerases may have an adverse impact on these phenotypes. Other studies point to a potential role of Rifr mutations in directly modulating transcription as a means of perturbing phenotype. For example, the RpoB H482Y mutant of B. subtilis RNAP (equivalent to H486Y of E. faecalis) appeared to inhibit Rho function, leading to enhanced rho autoregulation (16). In addition, a Rifr mutation in cluster I of B. subtilis RNAP led to enhanced transcription from sigA-dependent promoters (15), and several Rifr mutations in cluster I of Escherichia coli RNAP led to changes in promoter usage that mimic the stringent response (39). Although the latter two examples involve mutations at residues in Rif cluster I that are distinct from the equivalent of E. faecalis rpoB H486, they illustrate the point that Rifr-conferring mutations in the β subunit of RNAP can confer allele-specific changes in transcriptional profile and, by extension, phenotype. Additionally, a recent report (7) describes a mutation in rpoB of Staphylococcus aureus that, although it does not confer resistance to Rif, enhances resistance to daptomycin and vancomycin and leads to global changes in gene expression.

In light of these observations, we propose that specific Rifr mutations in the β subunit of E. faecalis RNAP result in altered transcription, particularly in genes that promote cephalosporin resistance. We predict that the rpoB H486Y allele leads to enhanced transcription of such genes, while the other Rifr alleles may lead to reduced transcription of the same genes. At this time, few specific genes are known to be required for cephalosporin resistance in E. faecalis. One of those genes is croR, which encodes the response regulator of a two-component signal transduction system that is required for normal cephalosporin resistance in E. faecalis (6, 12). CroR can regulate transcription of its target genes (22, 26), suggesting a possible mechanism in which mutations in RNAP may influence CroR-directed transcription of genes that are critical for cephalosporin resistance. Thus far, only a few CroR-dependent genes have been identified, none of which are known to play a role in cephalosporin resistance.

To probe for an impact of RNAP mutations on other known cephalosporin resistance determinants in E. faecalis, we assessed the abundance of IreK kinase in rpoB H486Y mutants via immunoblotting, but we did not observe any significant differences from that of the wild type. Similarly, a whole-cell penicillin-binding assay to probe levels of Pbp5 in rpoB H486Y mutants did not reveal any differences from that of the wild-type (data not shown). Therefore, it seems likely that as-yet-unknown genes that promote cephalosporin resistance exist. We are optimistic that ongoing study of the rpoB H486Y mutant will reveal new insights into the identity of those genes and the underlying mechanisms of cephalosporin resistance in E. faecalis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by program development funds from the MCW Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, by the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin program, and by grant AI081692 from the NIH (to C.J.K.).

We thank Michael Gilmore for providing strains and members of the Kristich laboratory for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Aarestrup FM, Butaye P, Witte W. 2002. Nonhuman reservoirs of enterococci, p 55–99 In Gilmore MS, et al. (ed), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arbeloa A, et al. 2004. Role of class A penicillin-binding proteins in PBP5-mediated β-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 186:1221–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aubry-Damon H, Soussy CJ, Courvalin P. 1998. Characterization of mutations in the rpoB gene that confer rifampin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2590–2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canepari P, Lleo MM, Cornaglia G, Fontana R, Satta G. 1986. In Streptococcus faecium penicillin-binding protein 5 alone is sufficient for growth at sub-maximal but not at maximal rate. J. Gen. Microbiol. 132:625–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clewell DB, et al. 1982. Mapping of Streptococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAD2 and studies relating to transposition of Tn917. J. Bacteriol. 152:1220–1230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Comenge Y, et al. 2003. The CroRS two-component regulatory system is required for intrinsic β-lactam resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 185:7184–7192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cui L, et al. 2010. An RpoB mutation confers dual heteroresistance to daptomycin and vancomycin in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:5222–5233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donskey CJ, et al. 2000. Effect of antibiotic therapy on the density of vancomycin-resistant enterococci in the stool of colonized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 343:1925–1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dunny GM, Brown BL, Clewell DB. 1978. Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:3479–3483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Floss HG, Yu TW. 2005. Rifamycin—mode of action, resistance, and biosynthesis. Chem. Rev. 105:621–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gold OG, Jordan HV, van Houte J. 1975. The prevalence of enterococci in the human mouth and their pathogenicity in animal models. Arch. Oral Biol. 20:473–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hancock LE, Perego M. 2004. Systematic inactivation and phenotypic characterization of two-component signal transduction systems of Enterococcus faecalis V583. J. Bacteriol. 186:7951–7958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hegstad K, Mikalsen T, Coque TM, Werner G, Sundsfjord A. 2010. Mobile genetic elements and their contribution to the emergence of antimicrobial resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:541–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hidron AI, et al. 2008. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29:996–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inaoka T, Takahashi K, Yada H, Yoshida M, Ochi K. 2004. RNA polymerase mutation activates the production of a dormant antibiotic 3,3′-neotrehalosadiamine via an autoinduction mechanism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:3885–3892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ingham CJ, Furneaux PA. 2000. Mutations in the beta subunit of the Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase that confer both rifampicin resistance and hypersensitivity to NusG. Microbiology 146:3041–3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jin DJ, Gross CA. 1988. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J. Mol. Biol. 202:45–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kristich CJ, Chandler JR, Dunny GM. 2007. Development of a host-genotype-independent counterselectable marker and a high-frequency conjugative delivery system and their use in genetic analysis of Enterococcus faecalis. Plasmid 57:131–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kristich CJ, Little JL, Hall CL, Hoff JS. 2011. Reciprocal regulation of cephalosporin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. mBio 2(6):e00199-11 doi:10.1128/mBio.00199-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kristich CJ, Manias DA, Dunny GM. 2005. Development of a method for markerless genetic exchange in Enterococcus faecalis and its use in construction of a srtA mutant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5837–5849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kristich CJ, Wells CL, Dunny GM. 2007. A eukaryotic-type Ser/Thr kinase in Enterococcus faecalis mediates antimicrobial resistance and intestinal persistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:3508–3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Le Breton Y, Muller C, Auffray Y, Rince A. 2007. New insights into the Enterococcus faecalis CroRS two-component system obtained using a differential-display random arbitrarily primed PCR approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3738–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maekawa S, Yoshioka M, Kumamoto Y. 1992. Proposal of a new scheme for the serological typing of Enterococcus faecalis strains. Microbiol. Immunol. 36:671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maughan H, Galeano B, Nicholson WL. 2004. Novel rpoB mutations conferring rifampin resistance on Bacillus subtilis: global effects on growth, competence, sporulation, and germination. J. Bacteriol. 186:2481–2486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McBride SM, Fischetti VA, Leblanc DJ, Moellering RC, Jr, Gilmore MS. 2007. Genetic diversity among Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One 2:e582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muller C, et al. 2006. The response regulator CroR modulates expression of the secreted stress-induced SalB protein in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 188:2636–2645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murray BE. 1990. The life and times of the Enterococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3:46–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nicholson WL, Maughan H. 2002. The spectrum of spontaneous rifampin resistance mutations in the rpoB gene of Bacillus subtilis 168 spores differs from that of vegetative cells and resembles that of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 184:4936–4940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ozawa Y, De Boever EH, Clewell DB. 2005. Enterococcus faecalis sex pheromone plasmid pAM373: analyses of TraA and evidence for its interaction with RpoB. Plasmid 54:57–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palmer KL, et al. 2010. High-quality draft genome sequences of 28 Enterococcus sp. isolates. J. Bacteriol. 192:2469–2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reference deleted.

- 32. Perkins AE, Nicholson WL. 2008. Uncovering new metabolic capabilities of Bacillus subtilis using phenotype profiling of rifampin-resistant rpoB mutants. J. Bacteriol. 190:807–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Signoretto C, Boaretti M, Canepari P. 1994. Cloning, sequencing and expression in Escherichia coli of the low-affinity penicillin binding protein of Enterococcus faecalis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123:99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tannock GW, Cook G. 2002. Enterococci as members of the intestinal microflora of humans, p 101–132 In Gilmore MS, et al. (ed), The enterococci: pathogenesis, molecular biology, and antibiotic resistance. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tomasz A. 1979. The mechanism of the irreversible antimicrobial effects of penicillins: how the beta-lactam antibiotics kill and lyse bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 33:113–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35a. Vesic D, Kristich CJ. 30 January 2012. MurAA is required for intrinsic cephalosporin resistance of Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. doi:10.1128/AAC.05984-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vogler AJ, et al. 2002. Molecular analysis of rifampin resistance in Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus cereus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:511–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wehrli W, Knusel F, Schmid K, Staehelin M. 1968. Interaction of rifamycin with bacterial RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 61:667–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zapun A, Contreras-Martel C, Vernet T. 2008. Penicillin-binding proteins and beta-lactam resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:361–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhou YN, Jin DJ. 1998. The rpoB mutants destabilizing initiation complexes at stringently controlled promoters behave like “stringent” RNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:2908–2913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]