Abstract

A new strategy to develop an effective vaccine is essential to control food-borne Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis infections. Bacterial ghosts (BGs), which are nonliving, Gram-negative bacterial cell envelopes, are generated by expulsion of the cytoplasmic contents from bacterial cells through controlled expression using the modified cI857/λ PR/gene E expression system. In the present study, the pJHL99 lysis plasmid carrying the mutated lambda pR37-cI857 repressor and PhiX174 lysis gene E was constructed and transformed in S. Enteritidis to produce a BG. Temperature induction of the lysis gene cassette at 42°C revealed quantitative killing of S. Enteritidis. The S. Enteritidis ghost was characterized using scanning and transmission electron microscopy to visualize the transmembrane tunnel structure and loss of cytoplasmic materials, respectively. The efficacy of the BG as a vaccine candidate was evaluated in a chicken model using 60 10-day-old chickens, which were divided into four groups (n = 15), A, B, C, and D. Group A was designated as the nonimmunized control group, whereas the birds in groups B, C, and D were immunized via the intramuscular, subcutaneous, and oral routes, respectively. The chickens from all immunized groups showed significant increases in plasma IgG and intestinal secretory IgA levels. The lymphocyte proliferation response and CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ T cell subpopulations were also significantly increased in all immunized groups. The data indicate that both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are robustly stimulated. Based on an examination of the protection efficacy measured by observations of gross lesions in the organs and bacterial recovery, the candidate vaccine can provide efficient protection against virulent challenge.

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, a Gram-negative intracellular pathogen, is one of the bacteria most frequently isolated from human infections worldwide (45). Recent studies estimate there are 80.3 million annual cases of food-borne disease related to Salmonella worldwide (21). S. Enteritidis represents the most commonly isolated human salmonellosis Salmonella serovar within the European Union and South Korea (10, 18). Infected poultry meat and eggs are the primary repositories for S. Enteritidis associated with human illness (39). As poultry are the most important source of S. Enteritidis for humans, measures limiting S. Enteritidis prevalence in poultry are continuously being sought. Because the frequency of antimicrobial resistance and the number of resistance determinants in Salmonella have risen markedly (13), vaccination plays an important role in the overall biosecurity system on chicken farms to prevent Salmonella infections. Several formulations of live attenuated, killed, and subunit vaccines have been used in an attempt to control S. Enteritidis (29, 33, 42). The commercial vaccines available against S. Enteritidis are mostly inactivated formulations; however, these strategies can affect the physiochemical/structural properties of surface antigens and thereby negatively affect the development of protective immunity. Killed bacteria and subunit-based vaccines elicit a good humoral response but lack the ability to induce a strong cell-mediated immune (CMI) response (2). Live attenuated mutants are capable of producing both humoral and CMI responses, but major drawbacks include potential reversion virulence and environmental contamination via fecal shedding (19). Thus, formulating safe vaccine candidates that can overcome the drawbacks of live and killed vaccines is necessary to protect chickens against S. Enteritidis.

Genetically inactivating pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria by controlled expression of the cloned bacteriophage PhiX174 lysis gene E offers a promising new approach in non-live vaccine technology for protection against infectious diseases (14). Gene E expression is controlled by the rightward phage λ PR promoter and the corresponding temperature-sensitive repressor, cI857, which is inactivated at temperatures of >30°C. However, suboptimal growth temperatures reduce the rate of division and thus slow down bacterial-ghost (BG) production. Heat stability can be conferred on the cI857/λ PR/gene E expression cassette by introducing the mutation in the rightward λ PR promoter; thus, gene E expression is stringently repressed at temperatures up to 37°C and is activated at 42°C (16). Gene E codes for a 91-amino-acid polypeptide that assembles and penetrates the inner and outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria, leading to the formation of a transmembrane tunnel structure through the cell envelope, resulting in the loss of the cytoplasmic contents. The morphology of the bacteria, including all cell surface structures and the cell membranes, is not affected by the lysis event, except for the lysis hole (14). The resulting empty cell envelopes share the functional and antigenic determinants of the envelope with their living counterparts and are termed BGs (44).

In the present study, we constructed a lysis plasmid carrying the bacteriophage PhiX174 lysis gene E and the lambda PR-cI857 regulatory system. Expression of gene E was tightly repressed until 37°C by introducing a mutation in operator region 2 (OR2) of the rightward λ PR promoter by site-directed mutagenesis. The lysis plasmid was used to produce the S. Enteritidis ghost vaccine. Vaccination with the S. Enteritidis ghost induced both cellular and humoral immune responses and effectively protected chickens against virulent S. Enteritidis infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, bacterial strains, and plasmids.

Female Brown nick layer chickens were used and maintained on antibiotic-free feed and water ad libitum. All experimental work involving animals was approved (CBU 2011-0017) by the Chonbuk National University Animal Ethics Committee in accordance with the guidelines of the Korean Council on Animal Care. The bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used are listed in Table 1. All Escherichia coli and S. Enteritidis strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C in a shaking incubator at 180 rpm. Bacterial strains were stored as frozen cultures in LB broth containing 20% glycerol at −80°C until use.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli Top 10 | F−mcrA (mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) F80 lacZ M15 lacX74 recA1 ara 139(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr)endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| S. Enteritidis | ||

| JOL860 | S. Enteritidis wild-type from chicken | This study |

| JOL1313 | S. Enteritidis containing pJHL99 | This study |

| JOL1182 | S. Enteritidis virulent strain isolated from chicken salmonellosis | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy vector | Cloning vector; pUCori Ampr | Promega |

| pJHLP99 | Derivative of pGEM-T Easy vector containing a ghost cassette | This study |

| Ghost cassette-specific primers | ||

| XbaI ghost-Forward | 5′-TCTAGAGACCAGAACACCTTGCCGATC-3′ | This study |

| XbaI ghost-Reverse | 5′-TCTAGAACATTACATCACTCCTTCCG-3′ | |

| Primers for site-directed mutagenesis | ||

| SDM37-F | 5′-GGATAAATATCTAACACCGGCGTGTTGACTATTTTACC-3′ | |

| SDM37-R | 5′-GGTAAAATAGTCAACACGCGGGTGTTAGATATTTATCC-3′ | |

| Salmonella genus-specific primers | ||

| OMPC-Forward | 5′-ATCGCTGACTTATGCAATCG-3′ | |

| OMPC-Reverse | 5′-CGGGTTGCGTTATAGGTCTG-3′ | 1 |

| S. Enteritidis-specific primers | ||

| ENT-F | 5′-TGTGTTTTATCTGATGCAAGAGG-3′ | |

| ENT-R | 5′-TGAACTACGTTCGTTCTTCTGG-3′ | 1 |

Construction of the lysis plasmid and transformation into S. Enteritidis.

The ghost cassette was comprised of the PhiX174 lysis E gene and the lambda pR37-cI857 regulatory system. A mutation in the ghost cassette was introduced using the QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Primers for mutagenesis were designed according to the manufacturer's instructions and contained the desired mutation in the middle of the primer with ∼10 to 15 bases of the correct sequence on either side (Table 1). The thermal profile for the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis reaction consisted of initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s followed by 12 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 5 min using an iCycler thermal cycler instrument (Bio-Rad, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom). The mutated ghost cassette was identified by DNA sequencing. The ghost cassette was gel purified and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and designated pJHL99. The pJHL99 plasmid (∼4.2 kb) was introduced into a wild-type S. Enteritidis strain (JOL860) by electroporation and designated JOL1313. This strain was used to produce the ghost.

Generation and characterization of the S. Enteritidis ghost.

A single colony of JOL1313 containing pJHL99 was inoculated in 100 ml of LB broth containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and incubated at 37°C. When the cultures reached the mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.5 to 0.6), E gene expression was induced by a temperature shift from 37 to 42°C. The induction of gene E-mediated bacteriolysis was monitored by measuring the OD600 and CFU of viable cells at different lysis time points (0, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h). After completion of lysis, the S. Enteritidis ghosts were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2). The final cell pellets were resuspended in sterile PBS and stored at −20°C until use. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were used to morphologically characterize the ghost. Samples from lysed and unlysed JOL1313 cells were harvested at the end of the lysis experiment by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min. Samples were prepared and analyzed by SEM and TEM as described previously (20, 35).

Immunization and challenge.

Sixty chickens were divided equally into four groups (n = 15) for ghost inoculation. All chickens were inoculated at 10 days of age. Based on our preliminary experimental data, the doses of BGs for oral and parenteral immunization were determined (data not shown). Group A chickens were used as the control and were inoculated orally with PBS. Groups B and C were inoculated with 1 × 108 cells/0.1 ml via the intramuscular and subcutaneous routes, respectively. Group D chickens were inoculated with 1 × 1010 cells/0.1 ml/chicken via the oral route. All groups were challenged with 1 × 109 CFU/0.1 ml of a virulent S. Enteritidis strain (JOL1182) via the oral route at 3 weeks postvaccination.

Assessment of humoral immune responses.

The presence of specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and secretory IgA (sIgA) antibodies against S. Enteritidis antigens following immunization was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Plasma and intestinal-wash fluid were collected from five birds in each group to evaluate systemic IgG and intestinal secretory IgA, respectively. Plasma samples were collected by centrifuging heparinized blood samples collected from the wing vein, and the intestinal wash samples were collected as described previously (24). An indirect ELISA was performed with an outer membrane protein (OMP) fraction extracted from JOL860 as described previously (17). The plasma samples were diluted 1:80, and the intestinal-wash samples were diluted 1:4. The presence of plasma IgG and intestinal sIgA against the OMP was identified using a chicken IgG and IgA ELISA quantitation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX).

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

The lymphocyte proliferation assay was performed to determine lymphocyte activation and cell-mediated immune responses (23). The sonicated bacterial protein suspension prepared from JOL860 was as described previously (43). Blood was collected from five birds in each group, and peripheral lymphocytes were separated using the gentle swirl technique (11). Trypan blue dye exclusion testing was performed to assess cell viability. A viable mononuclear cell suspension at 1 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 g/ml streptomycin, and 2 g/ml Fungizone was incubated in triplicate in 96-well tissue culture plates with either 4 μg/ml of sonicated bacterial protein suspension or 10 μg/ml of concanavalin A (ConA) or RPMI alone at 40°C (in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 72 h). The proliferation of stimulated lymphocytes was measured using ATP bioluminescence as a cell viability marker with the ViaLight Plus kit (Lonza, Rockland, ME) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The emitted light intensity was measured with a luminometer (TriStarLB941; Berthold Technologies GmbH, Bad Wildbad, Germany) with an integrated program for 1 s. The blastogenic response against a specific antigen was expressed as the mean stimulation index (SI), which is calculated by dividing the mean luminescence emitted by antigen-stimulated cultures by the mean luminescence emitted by nonstimulated control cultures (23).

Flow cytometric analyses.

For examination of changes in T cell populations, blood samples were collected from 5 birds in each group, and suspensions of peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) were prepared using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 100 μl of 1 × 106 cells was incubated with appropriately diluted fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-CD3, biotin-labeled anti-CD4, and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-CD8a monoclonal antibodies (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) in the dark at 4°C for 30 min. After being washed three times with cold PBS, the cells were incubated with 100 μl of appropriately diluted allophycocyanin-labeled streptavidin monoclonal antibody (Southern Biotech) in the dark at 4°C for 30 min. After the incubation, all samples were washed three times with cold PBS and then resuspended in 0.5 ml of PBS. The single-color positive controls were prepared by staining representative cells with FITC-labeled anti-CD3, biotin-labeled anti-CD4, and PE-labeled anti-CD8a antibodies individually and used for estimation of proper compensation. The unstained cell sample was used as a negative control to adjust the correct voltage. The analysis was performed with a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, NJ) equipped with Cell Quest software on the same day. A total of 10,000 events per sample were recorded, and the percentages of positively stained cells were calculated.

Observation of gross lesions and bacteriological analysis of challenged birds.

A bacteriological analysis was carried out to determine persistence and clearance of the challenge strain from internal organs, such as the liver, spleen, and cecum, to evaluate the protective efficacy of JOL1313 against virulent S. Enteritidis challenge. The chickens in all groups were euthanized at days 7 and 14 postchallenge. A gross lesion score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 was given based on the number of necrotic foci on the organ and the extent of organ enlargement. A score of 0 indicated no lesion, a score of 1 was assigned to necrotic foci, a score of 2 indicated enlarged and necrotic organs, and a score of 3 was associated with more debilitated, necrotic, and distorted organs (31). Aseptically collected tissue samples were homogenized and preenriched in 3 ml buffered peptone water (BPW) (Becton Dickinson and Company), and 100 μl of homogenates was plated on brilliant green agar (BGA) (Becton Dickinson and Company) for determination of the bacterial count on direct culture. Overnight-incubated homogenates in BPW were inoculated in Rappaport-Vassiliadis R 10 (RV) broth (Becton Dickinson and Company) at 42°C for 48 h for selective enrichment of JOL1182. A loop of enrichment culture was streaked on BGA and incubated overnight at 37°C. Samples positive on direct and enrichment cultures were confirmed by PCR using Salmonella genus-specific and S. Enteritidis-specific primers (Table 1) (1). The number of direct-culture bacterial colonies was determined and expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean log10 CFU/g. Samples that were positive only after enrichment were counted as 1 CFU/g, and samples that yielded no Salmonella growth after enrichment were counted as 0 CFU/g. An S. Enteritidis-positive bird was defined based on recovery of S. Enteritidis from any of the internal organs (liver, spleen, and cecum) studied in an assay. The percent efficacy of protection for a particular group was calculated based on the number of S. Enteritidis-positive birds out of the total number of birds in a group (31).

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Analyses were performed with SPSS version 16.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL). An independent sample t test was used to analyze statistical differences in the immune responses, gross lesions, and organ bacterial recovery between the immunized groups and an unimmunized control group. Differences were considered significant when P values were ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Construction of a plasmid-based gene E lysis cassette to generate the S. Enteritidis ghost.

The pGEM-T Easy vector was used as the backbone to construct the pJHL99 lysis plasmid. The ghost cassette consisted of the PhiX174 gene E, which is under lambda PR promoter transcriptional control. The lambda PR promoter of the ghost system was prepared by introducing a point mutation in the OR. The bacteriophage λ PR operator consisted of three ORs; the nucleotide sequence of OR2 was composed of 5′-TAACACCGTGCGTGTTG-3′ and is mutated from T to C at the ninth nucleotide. This point mutation in the operator region leads to efficient repression by cI857 at higher temperatures than with the wild-type operator sequence. The promoter is tightly repressed by cI857 binding to the modified operator region at temperatures of ≤37°C and is induced at higher temperature, leading to lysis.

Production and characterization of the BG.

The pJHL99 lysis plasmid was successfully transformed into the S. Enteritidis wild-type strain JOL860, and ghost cells were produced by protein E-mediated lysis of bacterial cells. Production of ghosts from JOL1313 was carried out by increasing the incubation temperature from 37°C to 42°C during the mid-logarithmic growth phase (OD600, 0.5 to 0.6) to activate gene E. The OD of the JOL1313 cultures decreased during the first few hours after induction of gene E expression as a function of cell lysis and remained almost constant until the BGs were harvested (Fig. 1I). The number of CFU decreased rapidly after the temperature was increased, and no viable cells were detected at 48 h postinduction (Fig. 1II). The efficiency of gene E-mediated lysis in the nonlyophilized ghost cell preparation was almost 100%, as no colony was found in CFU tests during five replicate experiments. In contrast, wild-type S. Enteritidis JOL860 growth was not hampered at 42°C for up to 48 h (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Growth and lysis of JOL1313 containing pJHL99 and of JOL860, naïve wild-type S. Enteritidis. At time zero, the cultures were shifted from 37°C to 42°C. Gene E-mediated lysis of JOL1313 resulted in a dramatic decrease in the OD600 (I) and CFU/ml (II).

An electron microscopic analysis of S. Enteritidis ghosts was performed to reveal changes in the cellular morphology of ghosts compared with that of unlysed cells. SEM revealed the presence of a lysis tunnel structure within the S. Enteritidis ghost envelope (Fig. 2I, arrowheads), whereas the unlysed JOL1313 cells grown at 37°C showed no phenotypic alterations (Fig. 2II). The lysis tunnel structure was not randomly distributed over the cell envelope but was restricted to potential cell division sites, predominantly in the middle of the cell or at polar sites. Analysis of ultrathin S. Enteritidis ghost sections by TEM revealed partial disruption of the cytoplasmic membrane and cell wall accompanied by a loss of cytoplasmic material (Fig. 2III), whereas the cell membrane and cytoplasm were intact in unlysed cells (Fig. 2IV).

Fig 2.

Electron microscopic analyses of JOL1313 by SEM (I and II) and TEM (III and IV). (I and III) Presence of transmembrane tunnels, indicated by arrowheads, and loss of cytoplasmic material after lysis. (II and IV) Intact bacteria before lysis.

Humoral immune response.

The induction of humoral immune responses against the S. Enteritidis-specific antigen was monitored during the weeks after vaccination to evaluate the immunogenicity of the S. Enteritidis ghost as a vaccine candidate. Serum IgG levels in all immunized groups were significantly elevated at 2 and 3 weeks postvaccination compared to those in the control group (Fig. 3, left). At 3 weeks postvaccination, the serum IgG titers in groups B, C, and D increased compared to those in group A by approximately 4.8-, 4.4-, and 2.1-fold, respectively (P < 0.05). Among the immunized groups, serum IgG titers in group D were significantly lower than those in groups B and C (P < 0.05). The levels of mucosal secretary IgA in the intestinal-wash fluid increased significantly in all immunized groups at 3 weeks postvaccination compared with those in control group A (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3, right). At 3 weeks postvaccination, the increases in the sIgA concentration in intestinal-wash samples were 2.40-, 2.45-, and 2.86-fold in groups B, C, and D, respectively, compared with those in the corresponding control group A.

Fig 3.

Antigen-specific humoral immune responses in nonimmunized control (A), intramuscularly immunized (B), subcutaneously immunized (C), and orally immunized (D) groups were determined at each week postimmunization. (Left) Plasma IgG concentrations (ng/ml). (Right) Secretory IgA concentrations (ng/ml). Antibody levels are expressed as means ± standard errors of the mean. The asterisks indicate significant differences between the antibody titers of the immunized and nonimmunized groups (P < 0.05).

Lymphocyte proliferation assay.

The cellular immune response was examined by determining the ability of chicken peripheral mononuclear cells to show a proliferative response against stimulation with a sonicated bacterial protein suspension extracted from wild-type S. Enteritidis JOL860. At 3 weeks postimmunization, all immunized groups showed significant proliferative responses compared to that in the control (P < 0.05). The SIs of groups B, C, and D were 1.8, 2.4, and 1.4, respectively (Fig. 4). Higher SI values in immunized groups compared to the control reflected the dramatic increase in lymphocyte clonal proliferation, indicating improved immunological function after vaccination. Chickens in all groups responded similarly to stimulation with ConA (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Lymphocyte proliferative responses against S. Enteritidis-specific antigen in immunized and nonimmunized chickens at 3 weeks postvaccination. The antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferative response is expressed as the SI. The asterisks indicate significant differences between the SIs of the immunized and nonimmunized groups (P < 0.05). Group A, nonimmunized control; group B, intramuscularly immunized; group C, subcutaneously immunized; group D, orally immunized.

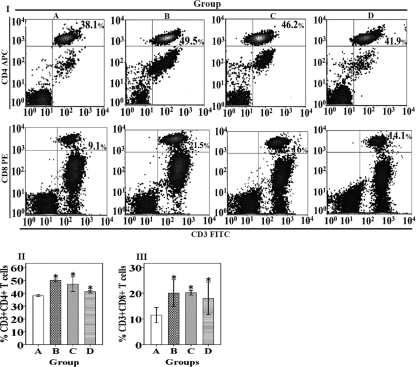

Flow cytometry analysis of T cell subsets.

To assess the CMI response after vaccination with the S. Enteritidis ghost vaccine, the T cell subpopulation profiles in PBL from all immunized and control groups were determined by flow cytometry. CD3 is a marker of the overall T cell population, whereas CD4 and CD8 are markers for helper T cells and cytotoxic T cells, respectively. At day 7 postvaccination, the overall population of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ cells increased significantly in all immunized groups compared to that in the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5I, II, and III).

Fig 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of T lymphocyte subpopulations. (I) Two-dimensional density plots for CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ T cell populations. The plots represent events for one representative chicken from each group. The population is represented as a percentage of gated cells. (II) CD3+ CD4+ T lymphocyte populations in immunized and nonimmunized chickens. (III) CD3+ CD8+ T lymphocyte populations in immunized and nonimmunized chickens. The values are shown as means ± standard errors of the mean of 5 chickens per group. The asterisks indicate significant differences between the T cell subpopulations of the immunized and nonimmunized groups (P < 0.05). Group A, nonimmunized control; group B, intramuscularly immunized; group C, subcutaneously immunized; group D, orally immunized.

S. Enteritidis ghost immunization protects against S. Enteritidis infection.

Chickens from all groups were euthanized at days 6 and 12 postchallenge to evaluate the protection efficacy of the ghost against S. Enteritidis infection. Lesion scores and challenge strain recovery from internal organs are presented in Table 2. The mean lesion scores for the liver and spleen from chickens in groups B, C, and D were significantly different from those of the control. The dissemination and persistence of the JOL1182 challenge strain in internal organs was examined by plating tissue homogenates directly onto BGA agar. Vaccinated birds from groups B, C, and D were protected against organ colonization by JOL1182. The levels of JOL1182 in the liver, spleen, and cecum of groups B and C were significantly lower on days 6 and 12 after challenge than those in the control (P < 0.05). A similar trend was evident in group D chickens, in which levels of the challenge strain in the liver, spleen, and cecum tended to be lower than in group A, though not statistically significantly, except the CFU count in the liver on day 6. The challenge strain isolated from positive samples was confirmed by PCR. After direct and enrichment cultures, the number of JOl1182-positive birds was significantly lower in groups B and C than in the control at days 6 and 12 postchallenge, whereas no significant difference was found in group D.

Table 2.

Gross lesions and recovery of challenge strain from internal organs of chickensa

| Day | Group | Lesion scoreb |

Bacterial recoverye |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver |

Spleen |

Cecum |

n/Ni | |||||||

| Liver | Spleen | CFU/gd | No. positivef | CFU/gd | No. positivef | CFU/gd | No. positivef | |||

| 6 | A | 1.25 ± 0.82 | 1.37 ± 0.7 | 1.26 ± 0.67 | 7/8 | 1.93 ± 1.33 | 6/8 | 1.7 ± 1.52 | 5/8 | 8 (0) |

| B | 0.25 ± 0.4c | 0.5 ± 0.7c | 0.12 ± 0.33g | 1/8h | 0.30 ± 0.53g | 2/8h | 0.12 ± 0.33g | 1/8h | 3 (62.5) | |

| C | 0.37 ± 0.5c | 0.6 ± 0.5c | 0.12 ± 0.33g | 1/8h | 0.34 ± 0.91g | 1/8h | 0.25 ± 0.43g | 2/8h | 3 (62.5) | |

| D | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.75 ± 0.4 | 0.37 ± 0.48g | 3/8h | 0.73 ± 0.93 | 4/8 | 1.06 ± 1.38 | 3/8 | 5 (37.5) | |

| 12 | A | 0.85 ± 0.83 | 1 ± 0.53 | 0.57 ± 0.49 | 4/7 | 1.35 ± 1.05 | 5/7 | 0.71 ± 0.45 | 5/7 | 6 (14) |

| B | 0 ± 0c | 0 ± 0c | 0 ± 0g | 0/7h | 0 ± 0g | 0/7h | 0 ± 0g | 0/7h | 0 (100) | |

| C | 0 ± 0c | 0 ± 0c | 0 ± 0g | 0/7h | 0 ± 0g | 0/7h | 0 ± 0g | 0/7h | 0 (100) | |

| D | 0.28 ± 0.45 | 0.57 ± 0.5 | 0.14 ± 0.37 | 1/7 | 0.71 ± 0.45 | 5/7 | 0.28 ± 0.45 | 2/7 | 5 (29) | |

Chickens from nonimmunized control (A), intramuscularly immunized (B), subcutaneously immunized (C), and orally immunized (D) groups were challenged with 1 × 109 CFU of JOL1182 via the oral route. Statistical analysis was carried out by Mann-Whitney U test.

Gross lesion score observed in the livers and spleens of birds from each group after challenge (mean ± standard error of the mean).

Significantly lower gross lesion scores of the S. Enteritidis ghost-immunized groups compared to the control group (P < 0.05).

CFU/g recovered from tissues expressed in log10 values.

Challenge strain recovery by direct and enrichment cultures of liver, spleen, and ceca of birds.

Number of positive samples per total number of samples after bacterial recovery.

Significantly lower bacterial recovery from the S. Enteritidis ghost-immunized group than from the control group postchallenge (P < 0.05).

Significantly lower number of S. Enteritidis-positive birds from the S. Enteritidis ghost-immunized group than from the control group postchallenge (P < 0.05).

n/N, number of S. Enteritidis-positive birds per total number of birds in a group; the protection percentage of each group is shown in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Our new approach to produce a dead S. Enteritidis vaccine is based on regulated S. Enteritidis lysis by controlled expression of gene E, leading to the formation of empty cell envelopes, termed S. Enteritidis ghost cells. This genetic inactivation of bacteria does not cause any physical or chemical denaturation of the bacterial surface structure. Therefore, the intact bacterial surface of the ghost represents functional antigenic envelope structures of its living counterparts in the native state (14). Thus, one advantage of using BGs is preservation of surface antigens in their natural conformations (44). Properly establishing the genetic repression/expression system in a given Gram-negative bacterium determines the success of BG production. In the present study, we constructed a pJHL99 plasmid vector that harbors a ghost cassette comprising lysis gene E, the rightward lambda promoter, and a temperature-sensitive cI857 repressor. Expression of gene E cloned into the pJHL99 vector was placed under the transcriptional control of the thermosensitive λpR37-cI857 system. Bacterial growth is a prerequisite for gene E lysis, because the tunnel structure is formed only in the growing regions of the cell, such as the central division zone or the pole zone (22). Strains carrying a conventional ghost cassette system are generally able to survive at 28°C (15, 41), whereas the ghost strain used in the present study was grown at 37°C, which is the optimum temperature for normal growth of Salmonella (24, 31). As suboptimal growth temperatures reduce the rate of bacterial multiplication, they slow the production process of BGs. Early studies indicated that growth of Salmonella at lower temperatures affects lipopolysaccharide O-antigen size and distribution (26) and reduces fimbrial expression (40). These changes in surface structures may account for alterations in S. Enteritidis ghost antigenicity. The point mutation (T to C) induced in the operator region of the λ PR promoter enabled stable repression of gene E expression at temperatures up to 37°C. Lysis was not observed in S. Enteritidis cultures grown at 37°C, indicating the increased temperature stability of the λpR37-cI857 system. We succeeded in preparing S. Enteritidis ghosts by shifting the grown cultures (in mid-log phase) to 42°C. Lysis was induced at 3 to 6 h at 42°C with no further increase in the OD600, and the number of viable cells decreased dramatically (Fig. 1I and II). Expression of the membrane protein by gene E formed the transmembrane lysis tunnel, through which the S. Enteritidis cytoplasmic content was expelled and the empty bacterial envelopes devoid of cytoplasmic contents were formed (Fig. 2I and III). Expressed protein E acts by inhibiting peptidoglycan synthesis and preventing cell wall synthesis, which accounts for the reduced OD and number of viable cells during the lysis procedure (3). No viable cells were detected at the end of the lysis experiment, indicating enhanced lysis efficiency by gene E. Our results indicate that the pJHL99 ghost plasmid was successfully constructed and incorporated into S. Enteritidis to prepare a ghost vaccine.

BGs contain membrane and antigenic structures identical to those of live bacteria, including membrane proteins, fimbriae, lipopolysaccharide, and peptidoglycans. These molecules are recognized and engulfed by dendritic cells and macrophages in immunized animals, thus effectively stimulating humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. To date, BGs prepared from many pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria have been successfully evaluated for the ability to induce immunogenicity and to protect against lethal challenge in various animal models (9, 22). In the present study, the immunogenic potential of a chicken S. Enteritidis ghost was evaluated by vaccinating chickens via the intramuscular, subcutaneous, and oral routes. The systemic antibody response was strongly triggered, and serum IgG titers increased significantly in all immunized groups (Fig. 3, left). The antibody titers in groups B and C were higher than that in group D, indicating that parenteral immunization with the S. Enteritidis ghost was superior to the oral route for promoting systemic antibody production (28). Systemic antibodies are important to target Salmonella bacteria that escape from infected cells and travel via the extracellular space to distant tissue sites to establish new infection foci (8). Because the pathogen primarily targets the intestinal tract, mucosal immunity is more likely to be involved as a first line of defense (38). As with mammals, the chicken mucosal immune response is characterized by an IgA-dominated antibody profile. In particular, the involvement of mucosal IgA in protection against salmonellosis has been reported (4). Our study showed that S. Enteritidis ghost-specific mucosal secretory IgA significantly peaked at 3 weeks postvaccination in all immunized groups in comparison with that in the control group (Fig. 3, right). This secretory IgA peak in the intestinal mucus may limit mucosal colonization of S. Enteritidis by preventing adherence and thereby subsequent invasion of the bacteria to some extent (37). However, clearance of the challenge strain from the tissues depends on the degree of systemic humoral and cell-mediated immune response (6). Antibodies mediate Salmonella killing via an immune mechanism, such as opsonization or phagocytosis (7). However, exclusion of the serum antibody macromolecule by the cell membrane implies that the antibody has no effect against Salmonella bacteria located in the intracellular space (5). Inducing the CMI response is pivotal to resolve intracellular S. Enteritidis infections (6, 24, 34). Chickens immunized with killed S. Enteritidis vaccine fail to develop lymphocyte proliferative responses (33). As the ghosts harbor surface antigens identical to those of live bacteria, they induce a strong CMI response (12). A previous report regarding vaccination of chickens with Salmonella described the involvement of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response in protection (36). In the present study, we evaluated CMI by determining the S. Enteritidis antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferative response and the CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ T cell populations in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of the immunized and nonimmunized groups. Our data showed a significantly increased lymphocyte stimulation index in all immunized groups compared to that in the control (Fig. 4). Effective antigen processing and induction of changes in the T cell subpopulation after immunization are important aspects of immunity against intracellular organisms. Our data show that the population of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ cells increased significantly in groups B, C, and D compared to that in group A after immunization with the S. Enteritidis ghost (Fig. 5I, 5II, and 5III). CD4+ major histocompatibility complex type II (MHC II)-restricted T cells are important for protection against intracellular pathogens, as they are involved in the production of macrophage-activating factors (27, 36), assist B cells to produce more antibodies, and aid in generating Salmonella-specific CD8+ T cells (32). The CD8+ T cells differentiate into cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which play a protective role by liberating intracellular Salmonella from infected macrophages (8). In the present experiment, although the immune responses induced in chickens immunized via the oral route are significantly elevated in comparison with the control group, they are lower than the immune response induced via parenteral routes. A lower immune response elicited following oral delivery of nonreplicating antigens is frequently observed in chickens. This could be caused by degradation of antigenic material by digestive enzymes of the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, only a small amount of fully immunogenic material can reach the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), which may result in lower induction of immune response (30).

Immunological trials in various animal models have demonstrated the ability of BGs to induce a strong immune response accompanied by significant protection against virulent challenge (12, 25). To examine the protective efficacy of the candidate vaccine, gross lesions and bacterial persistence of the challenge strain in infected organs, such as the liver, spleen, and cecum, were observed in chickens after virulent challenge. Chickens from all immunized groups were protected against the virulent S. Enteritidis challenge, and groups B and C showed the highest protection rate, followed by group D. The clearance pattern of the challenge strain from the liver, spleen, and cecum observed in the immunized groups was significantly different than that in the control (Table 2). The group D birds showed lower efficacy than groups B and C, but the immune responses induced in group D are significantly higher than in control group A. In terms of the protection efficacy in comparison with control group A, immunization of group D birds via the oral route significantly lowered the challenge strain load in the liver and considerably reduced it in the spleen and cecum (Table 2). These data indicate that immunization with the S. Enteritidis ghost via the oral route is effective. In a previous report, immunization of chickens with S. Enteritidis pathogenic island 2 proteins as the subunit vaccine protected organs against infection but did not protect against cecal colonization after challenge with a virulent S. Enteritidis strain (42). Based on our protection assay results, vaccination with the S. Enteritidis ghost prevented or reduced the bacterial counts in internal organs, which further decreased the chance for poultry food product contamination. Thus, effective implementation of S. Enteritidis ghost vaccination reduced the S. Enteritidis load in the food chain and may lead to a decrease in cases of human Salmonellosis caused by food poisoning.

Our results support the conclusion that the successfully constructed pJHL99 lysis plasmid was capable of inducing gene E-mediated lysis in S. Enteritidis to produce ghost cells. Immunizing chickens with the S. Enteritidis ghost induced both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses and afforded protection against S. Enteritidis challenge. Vaccination of chickens with the S. Enteritidis ghost vaccine was a safe approach for animals and the environment. Therefore, this vaccine represents a new tool to prevent Salmonella infection in poultry flocks and contributes significantly to establishing consumer confidence in safe poultry products.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Mid-Career Researcher Program through a National Research Foundation grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (no. 2011-0000076) of the Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alvarez J, et al. 2004. Development of a multiplex PCR technique for detection and epidemiological typing of Salmonella in human clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1734–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barrow PA. 2007. Salmonella infections: immune and non-immune protection with vaccines. Avian Pathol. 36:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernhardt TG, Roof WD, Young R. 2000. Genetic evidence that the bacteriophage fX174 lysis protein inhibits cell wall synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:4297–4302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berthelot-Hérault F, Mompart F, Zygmunt MS, Dubray G, Duchet-Suchaux M. 2003. Antibody responses in the serum and gut of chicken lines differing in cecal carriage of Salmonella Enteritidis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 96:43–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Casadevall A. 1998. Antibody-mediated protection against intracellular pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 6:102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chappell L, et al. 2009. The immunobiology of avian systemic salmonellosis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 128:53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Desmidt M, et al. 1998. Role of the humoral immune system in Salmonella Enteritidis phage type four infection in chickens. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 63:355–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dougan G, John V, Palmer S, Mastroeni P. 2011. Immunity to salmonellosis. Immunol. Rev. 240:196–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eko FO, et al. 2003. Evaluation of the protective efficacy of Vibrio cholera ghost (VCG) candidate vaccines in rabbits. Vaccine 21:3663–3674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. European Food Safety Authority 2007. Report of the task force on zoonoses data collection on the analysis of the baseline study on the prevalence of Salmonella in holdings of laying flocks of Gallus gallus. EFSA J. 97:1–84 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gogal RM, Ansar Ahmed S, Larsen CT. 1997. Analysis of avian lymphocyte proliferation by a new, simple, nonradioactive assay (Lympho-pro). Avian Dis. 41:714–725 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hensel A, et al. 2000. Intramuscular immunization with genetically inactivated (ghosts) Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 9 protects pigs against homologous aerosol challenge and prevents carrier state. Vaccine 18:2945–2955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hur J, Jawale C, Lee JH. 18 May 2011, posting date Antimicrobial resistance of Salmonella isolated from food animals: a review. Food Res. Int. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2011.05.014 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jalava K, Hensel A, Szostak M, Resch S, Lubitz W. 2002. Bacterial ghosts as vaccine candidates for veterinary applications. J. Control Release 85:17–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jechlinger W, et al. 2005. Comparative immunogenicity of the hepatitis B virus core 149 antigen displayed on the inner and outer membrane of bacterial ghosts. Vaccine 23:3609–3617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jechlinger W, Szostak MP, Witte A, Lubitz W. 1999. Altered temperature induction sensitivity of the lambda pR/cI857 system for controlled gene E expression in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173:347–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang HY, Srinivasan J, Curtiss R., III 2002. Immune responses to recombinant pneumococcal PspA antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine. Infect. Immun. 70:1739–1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kang ZW, et al. 2009. Genotypic and phenotypic diversity of Salmonella enteritidis isolated from chickens and humans in Korea. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 71:1433–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kwon HJ, Cho SH. 2011. Pathogenicity of SG 9R, a rough vaccine strain against fowl typhoid. Vaccine 29:1311–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwon SR, Nam YK, Kim SK, Kim DS, Kim KH. 2005. Generation of Edwardsiella tarda ghosts by bacteriophage PhiX174 lysis gene E. Aquaculture 250:16–21 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Majowicz S., Enteritidis, et al. 2010. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritidis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marchart J, et al. 2003. Pasteurella multocida- and Pasteurella haemolytica-ghosts: new vaccine candidates. Vaccine 21:3988–3997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsuda K, Chaudhari AA, Kim SW, Lee KM, Lee JH. 2010. Physiology, pathogenicity and immunogenicity of lon and/or cpxR deleted mutants of Salmonella Gallinarum as vaccine candidates for fowl typhoid. Vet. Res. 41:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matsuda K, Chaudhari AA, Lee JH. 2011. Evaluation of safety and protection efficacy on cpxR and lon deleted mutant of Salmonella Gallinarum as a live vaccine candidate for fowl typhoid. Vaccine 29:668–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mayr UB, et al. 2005. Bacterial ghosts as an oral vaccine: a single dose of Escherichia coli O157:H7 bacterial ghosts protects mice against lethal challenge. Infect. Immun. 73:4810–4817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McConnell M, Wright A. 1979. Variation in the structure and bacteriophage-inactivating capacity of Salmonella Anatum lipopolysaccharide as a function of growth temperature. J. Bacteriol. 137:746–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McSorley SJ, Cookson BT, Jenkins MK. 2000. Characterization of CD4+ T-cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella Typhimurium. J. Immunol. 164:986–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meenakshi M, et al. 1999. Adjuvanted outer membrane protein vaccine protects poultry against infection with Salmonella enteritidis. Vet. Res. Commun. 23:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Methner U, Barrow PA, Berndt A, Rychlik I. 2011. Salmonella Enteritidis with double deletion in phoPfliC—a potential live Salmonella vaccine candidate with novel characteristics for use in chickens. Vaccine 29:3248–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Muir WI, Bryden WL, Husband AJ. 2000. Immunity, vaccination and the avian intestinal tract. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 24:325–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nandre RM, Chaudhari AA, Matsuda K, Lee JH. 2011. Immunogenicity of a Salmonella Enteritidis mutant as vaccine candidate and its protective efficacy against Salmonellosis in chickens. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 144:299–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nauciel C. 1990. Role of CD4+ T cells and T-independent mechanisms in acquired resistance to Salmonella Typhimurium infection. J. Immunol. 145:1265–1269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Okamura M, Lillehoj HS, Raybourne RB, Babu U, Heckert R. 2003. Antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferation and interleukin production in chickens immunized with killed Salmonella enteritidis vaccine or experimental subunit vaccines. Avian Dis. 47:1331–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Okamuraa M, Lillehoja HS, Raybourneb RB, Babu US, Heckert RA. 2004. Cell-mediated immune responses to a killed Salmonella Enteritidis vaccine: lymphocyte proliferation, T-cell changes and interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, IL-2, and IFN-gamma production. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 27:255–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Panthel K, et al. 2003. Generation of Helicobacter pylori ghosts by PhiX protein E-mediated inactivation and their evaluation as vaccine candidates. Infect. Immun. 71:109–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Park SI, et al. 2010. Immune response induced by ppGpp-defective Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum in chickens. J. Microbiol. 48:674–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pasetti MF, Simon JK, Sztein MB, Levine MM. 2011. Immunology of gut mucosal vaccines. Immunol. Rev. 239:125–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith AL, Beal R. 2008. The avian enteric immune system in health and disease, p 243–271 In Davison F, Kaspers B, Schat KA. (ed), Avian immunology, 1st ed Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 39. Thomas ME, et al. 2009. Quantification of horizontal transmission of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis bacteria in pairhoused groups of laying hens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6361–6366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thorns CJ, Sojka MG, Mclaren IM, Dibb-Fuller M. 1992. Characterisation of monoclonal antibodies against a fimbrial structure of Salmonella Enteritidis and certain other serogroup D salmonellae and their application as serotyping reagents. Res. Vet. Sci. 53:300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tu FP, Chu WH, Zhuang XY, Lu CP. 2010. Effect of oral immunization with Aeromonas hydrophila ghosts on protection against experimental fish infection. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 50:13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wisner AL, et al. 2011. Immunization of chickens with Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Enteritidis pathogenicity island-2 proteins. Vet. Microbiol. 153:274–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Withanage GSK, et al. 2005. Cytokine and chemokine responses associated with clearance of a primary Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection in the chicken and in protective immunity to rechallenge. Infect. Immun. 73:5173–5182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Witte A, Wanner G, Lubitz W. 1992. Dynamics of PhiX174 protein E-mediated lysis of Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 157:381–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. World Health Organization 2005. WHO global salm-surv strategic plan, 2006–2010. Report of a meeting, Winnipeg, Canada WHO, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]