Abstract

In Escherichia coli, FtsN localizes late to the cell division machinery, only after a number of additional essential proteins are recruited to the early FtsZ-FtsA-ZipA complex. FtsN has a short, positively charged cytoplasmic domain (FtsNCyto), a single transmembrane domain (FtsNTM), and a periplasmic domain that is essential for FtsN function. Here we show that FtsA and FtsN interact directly in vitro. FtsNCyto is sufficient to bind to FtsA, but only when it is tethered to FtsNTM or to a leucine zipper. Mutation of a conserved patch of positive charges in FtsNCyto to negative charges abolishes the interaction with FtsA. We also show that subdomain 1c of FtsA is sufficient to mediate this interaction with FtsN. Finally, although FtsNCyto-TM is not essential for FtsN function, its overproduction causes a modest dominant-negative effect on cell division. These results suggest that basic residues within a dimerized FtsNCyto protein interact directly with residues in subdomain 1c of FtsA. Since FtsA binds directly to FtsZ and FtsN interacts with enzymes involved in septum synthesis and splitting, this interaction between early and late divisome proteins may be one of several feedback controls for Z ring constriction.

INTRODUCTION

Propagation of cells relies on division of a single cell into two viable daughter cells. In the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli, this process requires nearly a dozen essential proteins. Although functions have not been assigned to many of them, the order in which these proteins localize to the constriction site has been elucidated (27, 54). FtsZ, the first protein to localize, accumulates at the cell midpoint following the initial segregation of the newly replicated nucleoids (16). FtsZ is a homolog of eukaryotic tubulin and assembles into a polymeric ring that encircles the future division site (8, 20, 40). The ring is stabilized by FtsA and ZipA, which anchor FtsZ to the inner membrane (41, 45–47). After the accumulation of these early division proteins, later-stage proteins migrate to the Z ring to form a functional divisome (1). Once divisome assembly is complete, the Z ring constricts in front of the growing septum to separate the two daughter cells. Factors that trigger constriction are unknown.

Although a linear dependency order of division protein recruitment has been established, additional data suggest that many of the proteins interact outside of this simple framework (3, 11, 17, 28, 29, 36). For example, in vivo approaches have detected a significant interaction between the early division protein FtsA and two late essential division proteins, FtsI and FtsN (11, 36). These interactions involve subdomain 1c of FtsA, which encompasses residues 87 to 164 of the E. coli protein (53), because a fusion of the polarly localized protein DivIVA with FtsA or only the 1c subdomain was sufficient to drive green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions of FtsN or FtsI to the E. coli cell poles. Interactions between FtsA and other divisome proteins that require FtsA for their localization, such as FtsQ, were not detected by this assay (11). This interaction between FtsA and FtsN or FtsI was intriguing because the latter two proteins have bitopic topology, with only small N-terminal cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains that would be able to interact directly with the cytoplasmic FtsA protein, which is anchored peripherally to the inner membrane via its membrane targeting sequence (MTS) (45, 59). However, the ability to replace the MTS with a transmembrane segment from another protein and retain its function (50) argues against the MTS having any essential role in interactions with FtsI, FtsN, or other divisome proteins.

In addition to in vivo protein-protein interaction assays, a relationship between FtsA and FtsN is also suggested by genetic evidence. FtsN was originally identified as a multicopy suppressor of the temperature-sensitive ftsA12 mutant [ftsA12(Ts)] (13). Moreover, an unbiased search for bypass suppressors of FtsN led to the isolation of a point mutation in subdomain 1c of FtsA that allows modest cell division activity in the absence of FtsN (5). Finally, when ftsA was inactivated, premature targeting of later divisome proteins to the Z ring via fusions to the FtsZ-binding protein ZapA resulted in recruitment of all downstream divisome proteins except for FtsN (28, 29). This suggests that FtsN needs not only its predecessor, FtsI, but also at least FtsA to localize to the divisome. A recent study showed that FtsN uses two of its own periplasmic domains, a nonessential SPOR domain near the carboxy terminus and an essential 3-helix domain closer to the membrane, to self-enhance its proper septal localization (24). Other proteins needed for proper FtsN localization to the septum include FtsI (57) and at least one of three amidases, AmiA, AmiB, or AmiC (24). Other proteins implicated in genetic and/or physical interactions with FtsN include DamX and DedD, which, like FtsN, contain a SPOR domain and localize to the divisome (4, 24).

The previous evidence for FtsA-FtsN interaction suggested that early and late proteins could potentially interact as part of a feedback mechanism to regulate Z ring constriction in response to septum synthesis. However, because the previous in vivo assays were done in E. coli and were dependent on protein overproduction to generate the output signal, it was difficult to rule out the possibility that the observed interactions resulted from indirect interactions with other divisome proteins. In this study, we therefore took both in vivo and in vitro approaches, and we provide the first biochemical evidence for direct interaction between early and late essential divisome proteins in E. coli. We identify regions of FtsA and FtsN that are sufficient for their protein-protein interaction and suggest that self-association of FtsN positively influences interaction with FtsA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth media.

All E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C, unless otherwise indicated. LB medium was supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1; Fisher Scientific), kanamycin (50 μg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich), chloramphenicol (20 μg ml−1; Acros Organics), and glucose (1%; Sigma-Aldrich), as needed. Gene expression from pET28a, pKT25F, pUT18c, and pRR48 vectors was induced with isopropyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) at the indicated concentrations. Genes in pBAD30 and pBAD33 vectors were induced at a final concentration of 0.2% arabinose. JM109(DE3) and BL21(DE3) strains were used for expression from pET28a and its derivatives. All other vectors were transformed into XL1-Blue, DHMI, DH5α, or wild-type strain W3110 or WM1074. Strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| W3110 | Wild-type strain | Laboratory collection |

| WM1074 | MG1655 ΔlacU169 (TX3772) | Laboratory collection |

| WM1115 | WM1074 ftsA12 | Laboratory collection |

| WM1260 | BL21(DE3)/pWM1260 | |

| WM1835 | BL21(DE3)/pWM1833 | |

| WM2355 | FtsN depletion strain (ΔftsN::cat) with ftsN expressed from a plasmid with a Ts replication origin; Apr | 5 |

| WM2700 | W3110/pWM2700 | This study |

| WM2964 | FtsN depletion strain JKD42 (W3110 srl::Tn10 recA56 ΔftsN::kan); ftsN expressed from a plasmid with a Ts replication origin (pKD123) | 13 |

| WM3428 | BL21(DE3)/pWM2254 | |

| WM3616 | BL21(DE3)/pWM3616 | This study |

| WM4031 | WM2964/pDSW210 | This study |

| WM4033 | WM2964/pWM4032 | This study |

| WM4035 | WM2964/pWM4034 | This study |

| WM4049 | WM1074/pBAD33 | This study |

| WM4050 | WM1074/pWM4050 | This study |

| WM4051 | WM1074/pWM4051 | This study |

| XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac[F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15] Tn10 | Stratagene |

| BL21(DE3) | fhuA2 [lon] ompT gal(DE3) [dcm] ΔhsdS | Novagen |

| DH5α | fhuA2 Δ(argF-lacZ)U169 phoA glnV44 ϕ80 Δ(lacZ)M15 gyrA96 recA1 relA1 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 | Laboratory collection |

| DHMI | F−glnV44(AS) recA1 endA gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 spoT1 rfbD1 cya-854 | 36 |

| JM109 | endA1 recA1 gyrA96 thi hsdR17(rK− mK+) relA1 supE44 Δ(lac-proAB) [F′ traD36 proAB lacIqZΔM15] | Laboratory collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| Vectors | ||

| pBAD30 | Derivative of pDHB60 with araBAD promoter | 33 |

| pBAD33 | Derivative of pDHB60 with araBAD promoter | 33 |

| pDSW210 | Derivative of pBR322 with Ptrc promoter | 55 |

| pET28a | Expression vector with PT7 promoter | Novagen |

| pRR48 | Derivative of pBR322 with Ptac promoter and ideal lacO | J. S. Parkinson |

| Plasmids for two-hybrid assay | ||

| pKT25F | T25 fragment of B. pertussis cyaA (residues 1 to 224) in pSU40; FLAG sequence at N terminus of T25 | Modified from reference 36 |

| pUT18c | T18 fragment of B. pertussis cyaA (residues 225 to 399) in pUC19; compatible with pKT25F | 36 |

| pWM3021 | T18-ftsA in pUT18c | 51 |

| pWM3451 | T25-ftsN1-54-′phoA in pKT25F (residues 1 to 54 of FtsN plus residues 63 to 471 of PhoA) | This study |

| pWM3772 | T25-ftsN in pKT25F | This study |

| pWM3861 | T25-ftsN1-128 in pKT25F (residues 1 to 128 of FtsN) | This study |

| pWM3862 | T25-ftsN1-242 in pKT25F (residues 1 to 242 of FtsN) | This study |

| pWM3863 | T25-ftsNΔ63-130 in pKT25F (residues 1 to 62 plus 131 to 319 of FtsN) | This study |

| pWM3864 | T25-ftsNΔ63-130/Δ243-319 in pKT25F (residues 1 to 62 plus 131 to 242 of FtsN) | This study |

| pWM3865 | T25-ftsNΔ129-242 in pKT25F (residues 1 to 128 plus 243 to 319 of FtsN) | This study |

| pWM3866 | T25-virB101-60-′phoA in pKT25F (residues 1 to 60 of VirB10 plus residues 63 to 471 of PhoA) | This study |

| Other plasmids | ||

| pWM1260 | his6-ftsA in pET28a | 21 |

| pWM1833 | his6-ftsA-1c(85-170) in pET28a | This study |

| pWM2022 | ftsN in pBAD30 | 21 |

| pWM2254 | his6-ftsN in pET28a | This study |

| pWM2700 | flag-ftsA in pRR48 | This study |

| pWM2785 | flag-ftsA in pDSW210 | 50 |

| pWM3157 | flag-ftsN in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM3616 | his6-ftsNCyto-TM(1-55) in pET28a | This study |

| pWM3947 | his6-ftsNCyto(1-33)-AntiLeu-flag in pET28a | This study |

| pWM3948 | his6-ftsNCyto(1-33)-flag in pET28a | This study |

| pWM3949 | his6-ftsNCyto(1-33)-ParLeu-flag in pET28a | This study |

| pWM3950 | his6-ftsN-flag in pET28a | This study |

| pWM3951 | his6-ftsNCyto(1-33)-DDEE-ParLeu-flag in pET28a | This study |

| pWM4032 | ftsN-flag in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4034 | ftsNDDEE-flag in pDSW210 | This study |

| pWM4050 | his6-ftsNCyto-TM(1-55) in pBAD33 | This study |

| pWM4051 | his6-ftsN in pBAD33 | This study |

| pWM4093 | his6-gluglu-ftsA in pET28a | This study |

| pWM4094 | his6-gluglu-ftsA-1c(81-140) in pET28a | This study |

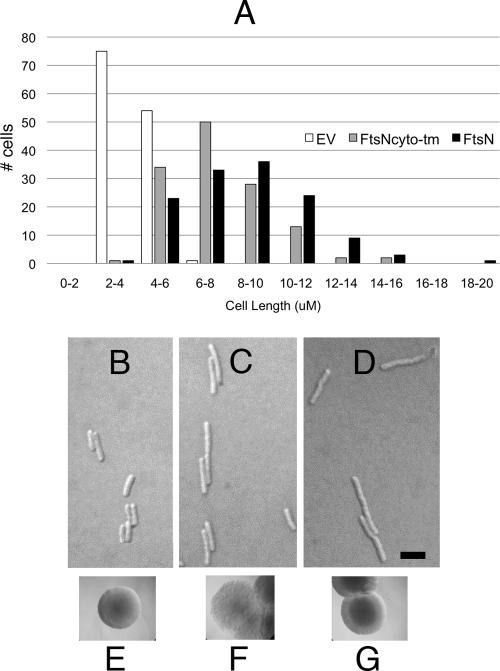

To measure the effects of overproduction of FtsN or the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of FtsN encompassing residues 1 to 55 (FtsNCyto-TM) on cell division, wild-type (WM1074) strains containing pBAD33 or pWM4051 were grown in LB plus chloramphenicol at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 0.1 and then induced with or without l-arabinose for 1.5 to 2 h before imaging cells and measuring cell lengths.

DNA and protein manipulation and analysis.

Standard protocols or manufacturers' instructions were used to isolate plasmid DNA, as well as for restriction endonuclease, DNA ligase, PCR, and other enzymatic treatments of plasmids and DNA fragments. Enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs, Inc. (NEB; Beverly, MA), and from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Plasmid DNA was purified using Wizard SV miniprep and PCR cleanup kits from Promega (Madison, WI). Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase was used as the high-fidelity PCR enzyme (NEB). Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL). DNA sequencing was performed by Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ). Oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Sequences of relevant primers used in PCR-based cloning are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The final versions of all relevant clones were sequenced to verify their construction.

Plasmid construction.

All plasmids are listed in Table 1. DNA sequences of leucine zipper chimeras and GluGlu-tagged FtsA proteins are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. The plasmid template used for ftsN constructs was pWM3157, which carries ftsN in pDSW210F as an XbaI-PstI fragment cloned by PCR amplifying the E. coli ftsN gene with primers 1115 and 1116. Constructs for overexpressing full-length or truncated ftsN fragments with epitope tags were cloned into pET28a (Novagen, EMD4 Biosciences), between EcoRI and HindIII sites. All contain carboxy-terminal FLAG tags, except for pWM2254 and pWM3616; pWM2254 was made using primers 112 and 113 to PCR amplify ftsN. FLAG tags were added to the 3′ ends of the PCR-amplified ftsN fragments by additional PCR amplification as described below.

Leucine zippers were added by combinatorial PCR (19). Primer 1520 was used as the forward primer in the following PCRs to clone ftsN. Plasmid pWM3950 contains full-length ftsN in pET28a, with an N-terminal His6 tag and a C-terminal FLAG tag; it was amplified using the forward primer 1520 in three sequential reactions using the partially overlapping primers 1562, 1565, and 1568, in that order, as the reverse primers. Plasmids pWM3616 and pWM3948 contain N-terminally His6-tagged derivatives of the first 55 codons of ftsN (encoding FtsNCyto-TM) and the first 33 codons of ftsN (encoding FtsNCyto-FLAG), respectively. The partially overlapping reverse primers 1564, 1566, and 1568, in that order, were used to make FtsNCyto-FLAG.

Plasmids pWM3949 and pWM3947 (see Fig. S2A and B in the supplemental material) contain the first 33 codons of ftsN (encoding FtsNCyto) followed by parallel and antiparallel leucine zipper motif sequences, respectively, immediately before the FLAG tags. The parallel leucine zipper was amplified from Saccharomyces cerevisiae GCN4 (34), encoded on plasmid pUTE1019-GCN4-zip, by using the forward primer 1552 in three sequential reactions with the partially overlapping reverse primers 1563, 1567, and 1568, in that order. The antiparallel leucine zipper was amplified from Bacillus subtilis mtaN (26), carried on plasmid pUTE1019-MtaN-CC, by using primers 1542 and 1547 as the forward and reverse primers, respectively. Both pUTE1019-GCN4-zip and pUTE1019-MtaN-CC were generously provided by the T. Koehler laboratory. FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG and FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG were made first by PCR amplifying the FtsNCyto fragment with primers 1520 plus 1553 and 1520 plus 1543, respectively. Combinatorial PCRs were subsequently performed using a mixture of appropriate PCR products in quasi-equimolar amounts, using the outside primers 1520 plus 1568 and 1520 plus 1547, respectively. The RRKK residues at positions 16 to 19 in the FtsNCyto portion in pWM3949 were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis to DDEE, using primers 1588 (forward primer) and 1589 (reverse primer), to create plasmid pWM3951, which encodes the His6-FtsNCyto-DDEE-ParLeu-FLAG mutant protein.

For in vivo overproduction or complementation experiments, His6-FtsN and His6-FtsNCyto-TM along with a strong ribosome binding site were cloned into pBAD33 directly as XbaI-HindIII fragments from pWM2254 and pWM3616, respectively, to make pWM4051 and pWM4050. For ftsN complementation experiments, ftsN-FLAG and ftsN-FLAG with the DDEE replacement at residues 16 to 19 were cloned into pDSW210 (55) between the EcoRI and XbaI sites, under the control of the weakened trc promoter, to make pWM4032 and pWM4034, respectively.

For bacterial adenylate cyclase two-hybrid (BACTH) assays, an N-terminal FLAG tag was inserted between the PstI and BglII sites of pKT25, using primers 1161 and 1162, to make pKT25F. To construct pKT25F-ftsN, pKT25F-ftsN1-128, and pKT25F-ftsN1-242, ftsN constructs were amplified and cloned into pKT25F as XbaI-KpnI fragments. We created pKT25F-ftsNΔ63-130 via a combinatorial PCR that fused ftsN1-62 (generated with primers 1191 and 1240) and ftsN131-319 (generated with primers 1239 and 1194). The combinatorial PCR product was digested with XbaI and KpnI and subsequently ligated to pKT25F. Using pKT25F-ftsNΔ63-130 as a template, ftsNΔ63-130/Δ243-319 was constructed by using primers 1191 and 1215 and cloned as described above to further truncate the ftsN construct. Plasmid pKT25F-ftsNΔ129-242 was constructed by using primers 1191 plus 1216 and 1217 plus 1194 and cloning with XbaI and KpnI sites. To create the ftsN1-54-′phoA chimera, ftsN1-54 was amplified using primers 1302 and 1303 and cloned as a blunt-ended SmaI fragment into a SmaI-cut pBluescript II derivative, pUI1160, containing ′phoA. The ftsN1-54 and ′phoA segments in this fusion were connected by a linker encoding ARGIDPR. The fusion was then amplified with primers 1191 and 1305 and inserted into pKT25F as an XbaI-KpnI fragment in frame with T25. The virB101-60-′phoA fusion was created by amplifying Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB101-60 (a gift from the P. Christie laboratory) with primers 1319 and 1320, which added EcoRV and PstI restriction sites, and cloning it into pUI1160 to fuse it to ′phoA. This chimera was then subcloned as an XbaI-KpnI fragment into pKT25F, using primers 1280 and 1305. The virB1-60 and ′phoA segments in this fusion were connected by a linker encoding PAARGIDPR.

The GluGlu tag was used as an additional tag for far-Western analysis. The sequence encoding the GluGlu epitope (EEEVMPME) (32) was added using primers 1579 and 1582 to the 5′ ends of the PCR-amplified fragments containing ftsA (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material). The ftsA fragments were amplified from pWM2785. Plasmid pWM4093 contains full-length ftsA, and pWM4094 (encoding His6-GluGlu-FtsA1c) contains the shortened 1c subdomain, from codons 81 to 140, preceded by an ATG and immediately followed by a stop codon. The shortened 1c subdomain (codons 81 to 140) was amplified using primers 1615 and 1616, and its amino-terminal GluGlu tag was amplified from DNA containing the full-length GluGlu-FtsA protein with primers 1613 and 1614, followed by combinatorial PCR using the outside primers 1613 and 1616. The PCR products containing GluGlu-tagged full-length or truncated ftsA fragments were cloned into pET28a between its NdeI and XhoI sites. Subdomain 1c, carrying residues 83 to 176 of FtsA but lacking a GluGlu tag, was cloned into pET28a between the NdeI and EcoRI sites to make pWM1833, which expresses subdomain 1c with an N-terminal His6 tag. Finally, the flag-ftsA overexpression plasmid pWM2700 was constructed by cloning flag-ftsA into a pRR48 derivative as described for other ftsA derivatives (5).

Protein purification.

Typically, His6-GluGlu-FtsA (see Fig. S2C in the supplemental material), His6-GluGlu-FtsA-1c-81-140, and His6-FtsA-1c-83-176 were purified from 4 liters of JM109(DE3) containing plasmid pWM4093, encoding full-length FtsA, or from BL21(DE3) containing plasmids pWM4094 and pWM1833, carrying subdomain 1c codons 81 to 140 and 83 to 176, respectively, grown at 30°C. The FtsA lysis buffer contained 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 25 mM potassium glutamate, and 5 mM MgCl2. Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was used at a 1 mM final concentration. Cells were lysed by three passages through a French pressure cell press (SLM Aminco, Rochester, NY). The cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 11,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. Talon metal affinity resin (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) was used for purification, following the manufacturer's instructions. Crude extracts were incubated with the resin for 2 h at 4°C prior to column purification. After washes in FtsA lysis buffer containing 5, 20, and 30 mM imidazole and elution in FtsA lysis buffer with 200 mM imidazole, the proteins were dialyzed three times at 4°C over a period of approximately 18 h against buffer containing 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 25 mM potassium glutamate, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 20% glycerol. The purified proteins were distributed in 100-μl aliquots and quick-frozen in a dry ice-ethanol bath prior to storage at −80°C. The purification procedure yielded proteins that were ≥95% pure (data not shown).

His6-FtsN-FLAG and His6-FtsNCyto-TM were purified from 12 liters of BL21(DE3) cells containing plasmids pWM3950 and pWM3616, respectively, grown at 30°C. The protocol was similar to that used for purification of FtsA, with the following modifications. The FtsN lysis buffer contained 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 200 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM PMSF. After clarification, the supernatant, which contained FtsN-loaded inner membranes, was centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The inner membrane pellet was solubilized in FtsN lysis buffer containing 1% Tween 20 by use of a Pyrex tissue grinder. The solubilized membranes were shaken in an orbital shaker for 2 h at 4°C and diluted at least 10-fold in FtsN buffer prior to incubation with the Talon resin. After washes in FtsN lysis buffer containing 5, 20, and 30 mM imidazole and elution in FtsN lysis buffer with 200 mM imidazole, the proteins were dialyzed three times at 4°C over a period of approximately 18 h against buffer containing 25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 25 mM potassium glutamate, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% Tween 20, and 20% glycerol.

His6-FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material), His6-FtsNCyto-FLAG, His6-FtsNCyto-DDEE-ParLeu-FLAG, and His6-FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG (see Fig. S2B) were purified from 4 liters of BL21(DE3) containing plasmids pWM3949, pWM3948, pWM3951, and pWM3947, respectively, grown at 30°C, following the same protocol as that used for the purification of FtsA but omitting the addition of DTT in the dialysis step. A BCA assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was used to determine protein concentrations.

Immunoblot analysis.

Crude extracts, eluates, and purified proteins were resuspended in SDS loading buffer, boiled for 10 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE in Mini Protean 3 cells (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), using 12% or 18% gels made with a 40% stock of 29:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by use of a wet apparatus. Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG and anti-His primary antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and monoclonal anti-GluGlu antibodies were purchased from Covance Research Products, Inc., Emeryville, CA. Anti-FtsA and anti-FtsN primary antibodies were produced in rabbits. A 1:2,000 dilution of primary antibody was used for detection of FLAG-FtsA in the eluate immunoblot shown in Fig. 3 and for detection of His-1c in the eluate immunoblot shown in Fig. 5. All other immunoblotting was done at a primary antibody dilution of either 1:5,000 or 1:10,000. Anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were used at a 1:10,000 dilution. SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific) and an Amersham ECL Plus Western blotting detection system (GE) were used for HRP detection.

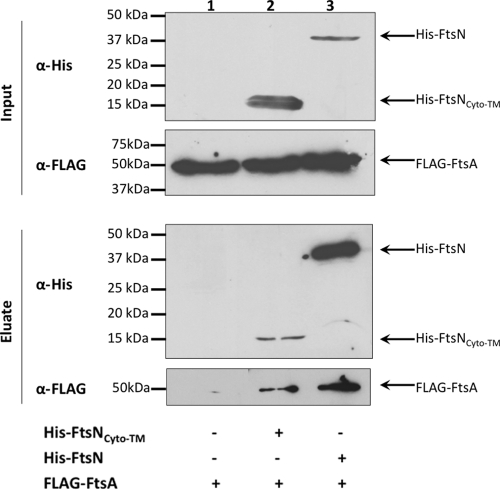

Fig 3.

Coaffinity purification of FLAG-FtsA and His6-FtsNCyto-TM. Crude extracts containing overexpressed FLAG-FtsA (WM2700) were combined with those containing His6-FtsNCyto-TM (WM3616) or His6-FtsN (WM3428) and treated as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

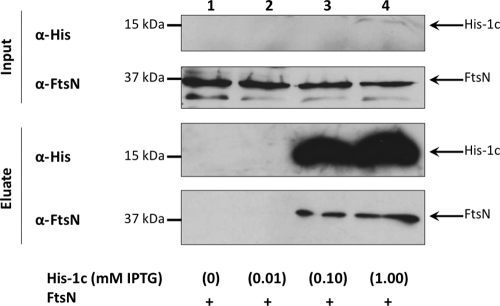

Fig 5.

Coaffinity purification of His6-FtsA-1c and FtsN. Crude extracts containing untagged FtsN (WM2022) were combined with those containing His6-FtsA-1c-83-176 (WM1835) induced at various IPTG concentrations (0, 0.01, 0.10, and 1.00 mM). Untagged FtsN was detected with anti-FtsN antibody.

Coaffinity purification.

Flasks containing 600 ml of LB were inoculated at a dilution of 1:100 from overnight cultures and grown in appropriate antibiotics to late logarithmic phase (OD600 = 0.6 to 0.8). During this phase, cultures were induced with 1 mM IPTG or 0.2% arabinose for 1.5 h, pelleted in a Beckman model J2-21 centrifuge with a JA-10 rotor at 9,000 rpm (14,300 × g), and stored at −80°C. Each protein of interest was overproduced from a separate strain, not from cocultured strains. Cell pellets were resuspended in low-ionic-strength buffer (50 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2) and lysed using a French press. Lysates were subjected to centrifugation with a JA-17 rotor at 9,000 rpm (11,200 × g) for 10 min at 4°C to pellet cellular debris. Crude extracts expressing different proteins were combined as indicated, and an aliquot was saved for detection of total protein levels prior to coaffinity purification. The remaining extracts were added to 5 ml of Talon metal affinity resin that was prewashed with low-ionic-strength buffer containing 5 mM imidazole to reduce nonspecific binding. Resin-crude extract mixtures were rocked at 4°C for 2 h before adding each to gravity flow columns. The resin was washed repeatedly with low-ionic-strength buffer containing 5 mM imidazole and 20 mM imidazole to remove non-specifically bound proteins. His6-tagged proteins as well as associated proteins were eluted with low-ionic-strength buffer containing 150 mM imidazole and subsequently concentrated 8-fold in Nanosep centrifugal devices (Pall Life Sciences). Crude extract aliquots and concentrated eluates were immunoblotted as described above. In the experiment to test the specificity of the coaffinity purification of His-FtsN and FLAG-FtsA, we used 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM KCl concentrations in the wash buffers.

BACTH experiments.

For BACTH experiments, FtsA was fused to the carboxy terminus of T18 from Bordetella pertussis by using the BACTH plasmid pUT18C. FtsN variants were fused to the carboxy terminus of T25 from Bordetella pertussis by using a modified version of the BACTH plasmid (referred to as pKT25F) that contains a FLAG sequence between the T25 fragment and the fused protein. Plasmids were heat shock transformed sequentially into competent DHM1 cells and grown at 30°C. Strains were streaked onto medium containing 50 μg ml−1 X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside; Gold Biotechnology), 0.5 mM IPTG, and antibiotics. Colonies were screened for a color change following 2 days of incubation at 30°C. Proper insertion of T25F-N1-54-PhoA and T25F-VirB101-60-PhoA into the cytoplasmic membrane was verified using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP; Sigma-Aldrich). Specifically, each construct was heat shock transformed into the phoA mutant strain DH5α and streaked onto medium containing 50 μg ml−1 BCIP and appropriate antibiotics.

Far-Western analysis.

Far-Western analysis was performed using purified His6-GluGlu-FtsA, His6-GluGlu-FtsA-1c-81-140, His6-FtsA-1c-83-176, His6-FtsN-FLAG, His6-FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG, His6-FtsNCyto-FLAG, His6-FtsNCyto-DDEE-ParLeu-FLAG, and His6-FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG. Typically, 1 to 3 μg of purified protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. FtsA buffer (see “Protein purification”) was used for all incubations and washes. After transfer, the membranes were blocked overnight (typically for 16 h) in FtsA buffer-5% nonfat dry milk. After blocking, the membranes used in the far-Western experiment were further incubated for 1 h at room temperature in fresh FtsA lysis buffer-5% dry milk-1% Tween 20 containing either native His6-GluGlu-FtsA, His6-GluGlu-FtsA-1c-81-140, or His6-FtsA-1c-83-176 at a concentration 6- to 10-fold higher than the amount loaded in the gels. After incubation with the appropriate proteins, the far-Western membranes were washed three times for 2 min each with FtsA buffer, and all membranes were incubated in FtsA buffer-5% dry milk containing the appropriate primary antibodies, followed by the typical immunoblotting protocol.

RESULTS

FtsA and FtsN interact in a coaffinity purification assay.

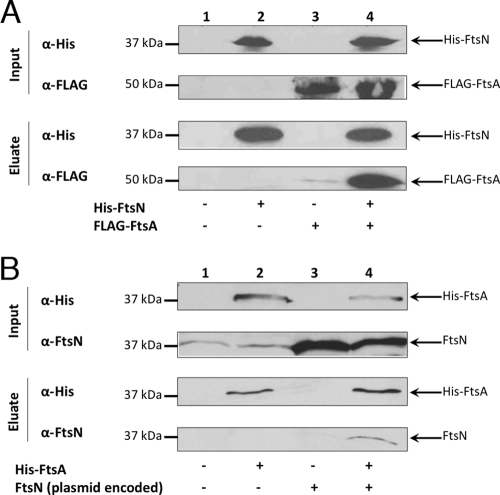

An interaction between FtsA and FtsN was suggested previously using the DivIVA polar recruitment assay and the BACTH method (11, 36). To confirm the interaction detected by these in vivo methods, we utilized coaffinity purification. Briefly, cell extracts containing His6-FtsN produced from WM3428 and FLAG-FtsA produced from WM2700 were combined and added to cobalt resin to immobilize His6-tagged FtsN and associated proteins. Following repeated washes, His6-FtsN was eluted with imidazole. Western blot analysis of the eluates detected a strong signal corresponding to FLAG-FtsA in the presence of His6-FtsN and a much weaker signal in the absence of His6-FtsN (Fig. 1A). This strong interaction was not affected by modest increases in ionic strength (up to 200 mM KCl) in the wash buffers (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Coaffinity purification of FtsA and FtsN from cobalt resin suggests an in vitro interaction. (A) Cells expressing His6-FtsN (WM3428) or FLAG-FtsA (WM2700) from plasmids were induced, pelleted, and lysed. Resulting crude extracts were mixed together and incubated with Talon cobalt resin. The resin was washed, and His6-FtsN was eluted with 150 mM imidazole. Crude extracts and eluates were immunoblotted with anti-His and anti-FLAG antibodies. (B) The protocol was repeated using crude extracts of His6-FtsA (WM1260) and untagged FtsN (WM2022) expressed from plasmids. Anti-FtsN antibody was used to detect untagged FtsN.

To further demonstrate FtsA-FtsN interaction by this method, the experiment was repeated with reverse tagging of the proteins (i.e., His6-FtsA and FLAG-FtsN). However, FLAG-FtsN was not detected in the eluate in the presence or absence of His6-FtsA (data not shown). Because the amino-terminal fusion of the FLAG tag to FtsN may have disrupted its interaction with His6-FtsA, we tested the interaction between an untagged variant of FtsN expressed from a plasmid (pWM2022) and His6-FtsA overproduced from pWM1260 [in BL21(DE3)]. Western blot analysis using anti-FtsN antibody detected coaffinity purification of untagged FtsN when His-FtsA was present but not when His-FtsA was absent (Fig. 1B). Therefore, copurification of FLAG-FtsA along with His6-FtsN, as well as untagged FtsN with His6-FtsA, provides the first in vitro evidence of FtsA-FtsN interaction. In addition, the inability of FLAG-FtsN and the ability of untagged FtsN to interact with His6-FtsA rule out an artifactual interaction between the His6 and FLAG tags.

The periplasmic region of FtsN is not required for interaction with FtsA.

To screen for the region(s) of FtsN required for FtsA-FtsN interaction, we used the BACTH assay to measure in vivo protein-protein interactions (37). In this assay, each protein of interest is fused to a complementary fragment of adenylate cyclase from Bordetella pertussis (T18 or T25) and expressed from two separate plasmids in a cya-deficient strain, in this case DHM1. Interaction between the proteins of interest forces interaction of the T18 and T25 fragments, reconstituting adenylate cyclase. This, in turn, results in cyclic AMP (cAMP)-cAMP receptor protein (CRP)-dependent expression of lacZ, which can be detected as blue colonies on LB plates containing both X-Gal and IPTG.

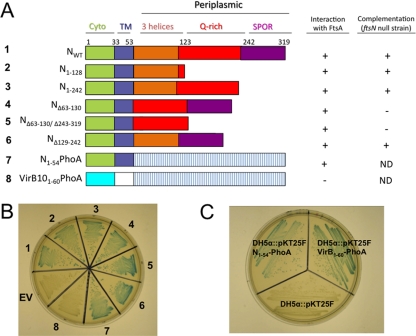

We engineered cells that coproduced wild-type FtsA from the BACTH plasmid pUT18c and variants of FtsN produced from the BACTH plasmid pKT25F (Fig. 2). As expected, full-length FtsN gave a positive interaction with FtsA (Fig. 2A and B). Various deletions of the periplasmic domain maintained a positive interaction with FtsA: for example, removal of the SPOR domain (N1-242), both the SPOR and Q-rich domains (N1-128), or both the SPOR and essential 3-helix domains (NΔ63-130/Δ243-319) retained the interaction with FtsA. Consistent with previously published results (14, 24, 59), T18 or T25 fusions of FtsN could complement an ftsN null mutant only if the 3-helix domain was present (Fig. 2A). Notably, however, FtsN lacking this domain or any other segment of the periplasmic domain continued to interact with FtsA.

Fig 2.

The periplasmic region of FtsN is not required for interaction with FtsA in BACTH assays. (A) FtsN variants were constructed in the BACTH plasmid pKT25F and cotransformed into the cya strain DHM1 with pUT18c-ftsA (pWM3021). Chimeras constructed with the secreted form of alkaline phosphatase (′PhoA) and the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens protein VirB10 are also shown. Positive interaction between the FtsA and FtsN variants is indicated by a plus symbol. Complementation of an FtsN depletion strain (WM2355) by the FtsN variants and chimeras is also shown. ND, not determined. (B) Interaction between the chimeras and FtsA was determined using medium containing X-Gal (50 μg ml−1) and IPTG (0.5 mM IPTG). All strains shown are in a DHM1 background, transformed with pUT18c-ftsA (pWM3021) and pKT25F-ftsN (pWM3772) (1), pKT25F-ftsN1-128 (pWM3861) (2), pKT25F-ftsN1-242 (pWM3862) (3), pKT25F-ftsNΔ63-130 (pWM3863) (4), pKT25F-ftsNΔ63-130/Δ243-319 (pWM3864) (5), pKT25F-ftsN129-242 (pWM3865) (6), pKT25F-ftsN1-54′phoA (pWM3451) (7), pKT25F-virB101-60′phoA (pWM3866) (8), or pKT25F empty vector (EV). (C) Successful translocation of N1-54-′PhoA and VirB101-60-′PhoA was confirmed in the phoA mutant strain DH5α, using BCIP-containing medium (50 μg ml−1).

Since all three periplasmic domains of FtsN were dispensable for the interaction with FtsA, we then tested if the remaining portion of FtsN, which included the cytoplasmic and transmembrane segments, was sufficient for the interaction. We therefore replaced the entire periplasmic region of FtsN with the secreted form of alkaline phosphatase (′PhoA), which has not been reported to interact with the divisome. Strikingly, this N1-54-′PhoA chimera still interacted strongly with FtsA in the BACTH assay (Fig. 2A and B).

To rule out the possibility of an interaction between ′PhoA and FtsA, ′PhoA was fused to the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of the unrelated Agrobacterium tumefaciens protein VirB10 (VirB101-60-′PhoA) and tested for interaction with FtsA. No interaction was detected between VirB101-60-′PhoA and FtsA, suggesting that ′PhoA does not facilitate the interaction between FtsA and FtsN1-54-′PhoA (Fig. 2A and B). To ensure that the VirB101-60-′PhoA fusion was expressed and translocated properly, we tested if the ′PhoA moiety of this fusion was active in the periplasm by using the phoA mutant strain DH5α to express N1-54-′PhoA and VirB101-60-′PhoA. Both strains produced blue colonies on BCIP-containing medium, confirming that ′PhoA was secreted into the periplasm (Fig. 2C). Together, these results strongly suggest that the periplasmic region of FtsN is dispensable for FtsA-FtsN interaction.

The cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of FtsN are sufficient for interaction with FtsA.

To determine if the remaining regions of FtsN are sufficient for interaction with FtsA, we asked whether the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of FtsN encompassing residues 1 to 55 (His6-FtsNCyto-TM; pWM3616) were sufficient to interact with FLAG-FtsA (produced from pWM2700) in a coaffinity purification experiment. Although His6-FtsNCyto-TM did not seem to bind to and/or elute from the cobalt resin as well as full-length His6-FtsN (Fig. 3, lane 2 versus lane 3, eluate), FLAG-FtsA was detectably coeluted in the presence of His6-FtsNCyto-TM, as shown in Western blots, suggesting that FLAG-FtsA interacts specifically with His6-FtsNCyto-TM (Fig. 3). This result therefore suggests that the predicted cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of FtsN are sufficient to interact with FtsA, in support of the BACTH results.

Purified FtsA and FtsN interact directly in vitro.

A positive result in the coaffinity purification assay suggested that the FtsA and FtsN proteins interact directly. One concern with this assay, however, is that other divisome proteins, which are probably also present in the extracts, may bridge an indirect FtsA-FtsN interaction, which would give a false-positive result. Some proteins, such as FtsI, can be ruled out as bridging proteins because of their low abundance (∼100 molecules/cell for FtsI [56]) relative to the overproduced levels of FtsA and FtsN that gave a positive interaction signal.

To prove a direct interaction more rigorously, we wanted to show that purified proteins could interact in the absence of a cell lysate, and we therefore engineered two strains. The first overproduced His6-GluGlu-FtsA, which could be affinity purified on a cobalt resin and detected with a monoclonal antibody directed against the GluGlu epitope. The His6-GluGlu-FtsA fusion was fully functional, as it was able to complement an ftsA12(Ts) strain (WM1115) as efficiently as wild-type FtsA (data not shown). The second strain overproduced His6-FtsN-FLAG, with FLAG at the periplasmic C terminus and thus unlikely to interfere with binding to FtsA. This tagged FtsN protein could fully complement the FtsN depletion strain WM2964 (data not shown). We purified both His6-GluGlu-FtsA (Fig. 4B, last lane) and His6-FtsN-FLAG (Fig. 4A, diagram 1, and B, lane 1) to near homogeneity.

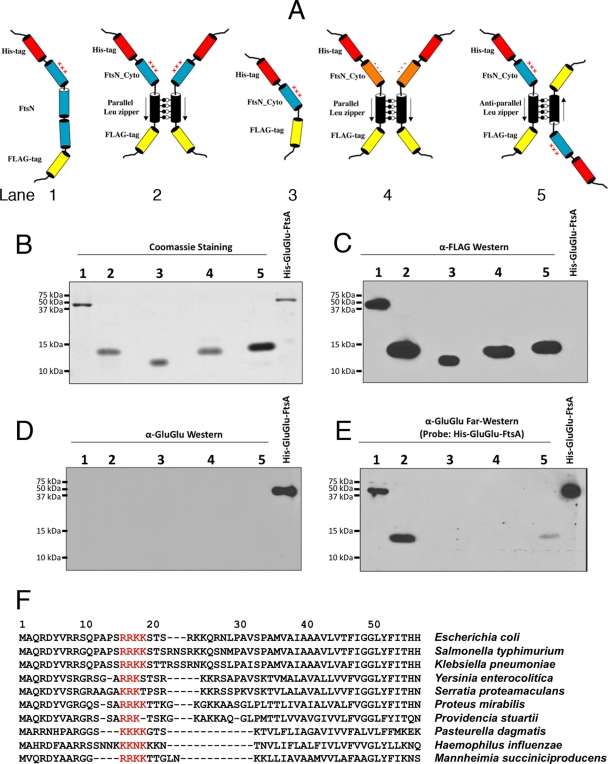

Fig 4.

Binding of purified FtsA to purified derivatives of FtsN and FtsNCyto. (A) Cartoon diagrams of the constructs used in this assay. The cylinders representing the different portions are color coordinated and refer to (i) the His6 tag (red), (ii) full-length FtsN or FtsNCyto (blue), (iii) the FLAG tag (yellow), (iv) GCN4 or MtaN leucine zippers (black), and (v) FtsNCyto with DDEE replacing RRKK16-19 (FtsNCyto-DDEE) (orange). Parallel and antiparallel leucine zippers are denoted by convergent and divergent arrows, respectively. The basic nature of the RRKK region is indicated by plus signs. Combined Western (C and D) and far-Western (E) results show binding of the purified His6-GluGlu-FtsA probe to His6-FtsN-FLAG and His6-FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG (lanes 1 and 2) but not to His6-FtsNCyto-FLAG, His6-FtsNCyto-DDEE-ParLeu-FLAG, or His6-FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG (lanes 3, 4, and 5, respectively). The purified proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and both loading and protein purity controls are shown in panel B by staining with Coomassie blue. His6-GluGlu-FtsA, loaded to the right of lane 5, was used as a negative control for anti-FLAG and a positive control for anti-GluGlu. The membrane in panel C was incubated with anti-FLAG antibody, and those in panels D and E were incubated with anti-GluGlu. The four gels were loaded and run identically. The reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods. (F) Alignment of FtsN cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains from the indicated species. The conservation of the basic patch of residues corresponding to residues 16 to 19 in E. coli is highlighted in red.

We used these purified proteins to test the interaction between FLAG-tagged FtsN and GluGlu-tagged FtsA by using protein overlay (far-Western) blots (15). His6-FtsN-FLAG from an SDS-PAGE gel was transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, allowing it to renature (9). The membrane was then overlaid with a solution containing purified His6-GluGlu-FtsA and immunoblotted with anti-GluGlu antibody. His6-GluGlu-FtsA from an SDS-PAGE gel was used as a positive control (Fig. 4B to E, last lanes). Importantly, His6-GluGlu-FtsA was strongly detected on the anti-GluGlu immunoblot, on top of the band corresponding to purified His6-FtsN-FLAG (Fig. 4E, lane 1). This result strongly suggests that the interaction between FtsA and FtsN is direct. Western blot analysis of purified His6-FtsN-FLAG with anti-GluGlu antibody detected no signal prior to incubation with His6-GluGlu-FtsA, eliminating the possibility of cross-reactivity between the anti-GluGlu antibody and His6-FtsN-FLAG (Fig. 4D, lane 1).

FtsA interacts preferentially with a dimerized FtsN cytoplasmic domain.

BACTH analysis and coaffinity purification suggested that the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of FtsN are necessary and sufficient for interaction with FtsA (Fig. 2 and 3). To further narrow down the region of FtsN involved in FtsA-FtsN interaction, the cytoplasmic portion of FtsN was purified using the same amino-terminal His6 tag as that for the full-length protein, with a carboxy-terminal FLAG tag also used for immunodetection (Fig. 4A, diagram 3, and B, lane 3). As shown in Fig. 4E, lane 3, His6-GluGlu-FtsA did not interact with His6-FtsNCyto-FLAG (called FtsNCyto-FLAG henceforth for brevity) on the far-Western blot, suggesting that the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN is not sufficient to interact with FtsA.

Because the cytoplasmic region of FtsN has a large number and proportion of basic residues, we hypothesized that the molecules of FtsNCyto-FLAG, even with the acidic FLAG residues present, might electrostatically repel each other. This putative lack of interaction between the FtsN constructs could in turn affect FtsA-FtsN interaction, as previous evidence suggests that FtsN interacts strongly with itself in vivo (3, 36). Indeed, FtsN self-interaction may be mediated by the transmembrane domains, because the N1-54-′PhoA chimera was able to interact with full-length FtsN in the BACTH assay (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We reasoned that forcing the FtsNCyto domains to interact in parallel might mimic the function of the potentially interacting transmembrane domains and restore the ability of FtsNCyto to bind to FtsA.

To force dimerization of the cytoplasmic region of FtsN independently of the transmembrane domain, we fused a parallel leucine zipper from GCN4, with a FLAG tag at its carboxy terminus, to the carboxy-terminal end of FtsNCyto (FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG) (Fig. 4A, diagram 2). We placed the ParLeu-FLAG tag at the carboxy terminus of FtsNCyto instead of the amino terminus with the idea that the artificial dimerization domain would functionally substitute for the FtsN transmembrane domain, which could potentially drive FtsNCyto dimerization (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). As a control, an antiparallel leucine zipper was also fused to the cytoplasmic domain to force neighboring cytoplasmic domains in opposing and aberrant orientations (FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG) (Fig. 4A, diagram 5; see Fig. S2).

We then separated similar quantities of these purified protein chimeras by SDS-PAGE and tested their ability to interact with purified His6-GluGlu-FtsA in far-Western assays. Notably, His6-GluGlu-FtsA interacted strongly with a band corresponding to the monomer size of FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG (Fig. 4E, lane 2). In contrast, His6-GluGlu-FtsA was detected only weakly in the lane corresponding to FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG (Fig. 4E, lane 5), again at the monomer size. Although mainly denatured by the SDS in the gel (42), these proteins probably renature on the nitrocellulose membrane after transfer. This could explain how a protein that should dimerize strongly would migrate as a monomer in the SDS-PAGE gel yet act as a dimer (or oligomer) in the far-Western blot. These results suggest that FtsNCyto is necessary and sufficient for interaction with FtsA, but only if FtsNCyto is in a parallel homodimer.

Role of a conserved patch of basic residues within the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN in interaction with FtsA.

After defining the FtsNCyto domain as sufficient for FtsA-FtsN interaction, we sought to identify specific residues within this domain that are important for this binary interaction. We noticed that amid the generally basic nature of the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN, there is a conserved patch of basic residues (RRKK) at amino acid positions 16 through 19 (Fig. 4F, red residues) that are sufficiently far from the predicted transmembrane domain to potentially be involved in a direct contact with FtsA. To begin to investigate the role of these residues in FtsA-FtsN interaction, we mutated the basic RRKK residues to acidic DDEE residues in the FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG construct to create FtsNCyto-DDEE-ParLeu-FLAG (Fig. 4A, diagram 4).

When His6-GluGlu-FtsA was used to probe FtsNCyto-DDEE-ParLeu-FLAG, which was on the same blot as the positively interacting FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG construct, only the latter band was detectable (Fig. 4B to E, compare lanes 4 with lanes 2). This indicated that mutation of residues 16 to 19 abolished the interaction and suggests that the basic patch in FtsNCyto is important for FtsA-FtsN interaction. To test this hypothesis in the context of full-length FtsN in vivo, we compared the abilities of pDSW210-FtsNDDEE-FLAG (pWM4034) and pDSW210-FtsN-FLAG (pWM4032) to complement an FtsN depletion strain (WM2964). Under depletion conditions for WM2964 at 42°C in LB medium, FtsN-FLAG and FtsNDDEE-FLAG each failed to complement the mutant at 0 mM IPTG, but they both complemented it fully at 1 mM IPTG (data not shown), indicating that the DDEE mutation has no significant deleterious effect on FtsN function in vivo. This is consistent with the ability to replace the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN with MalF, as shown previously (31), and suggests that the DDEE mutation does not grossly perturb protein structure or insertion into the membrane.

Subdomain 1c of FtsA is sufficient for interaction with FtsN.

Previous results from our laboratory suggested that subdomain 1c of FtsA is sufficient for recruitment of GFP-FtsN to the cell poles in an in vivo DivIVA recruitment assay (11). However, this effect could have been indirect. To verify the role of FtsA-1c in direct FtsA-FtsN interaction, we first tested the ability of His6-tagged FtsA-1c produced from pWM1833 to interact with untagged FtsN produced from pWM2022 in coaffinity purifications from cell lysates. Four cultures expressing His6-FtsA-1c were induced at increasing levels of IPTG (0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 mM) to create a gradient of His6-FtsA-1c. Crude extracts containing His6-FtsA-1c were combined with crude extracts of cells overproducing a stable level of untagged FtsN. As shown in Fig. 5, untagged FtsN was detected in the eluate when His6-FtsA-1c was at high levels after being induced by 0.1 or 1 mM IPTG but not when His6-FtsA-1c was at lower levels (induced by 0 or 0.01 mM IPTG). Although His6-FtsA-1c was difficult to detect in the lysates, it was significantly enriched in the eluates when it was induced by 0.1 or 1 mM IPTG. The coaffinity purification of untagged FtsN with His6-FtsA-1c suggests that the 1c subdomain of FtsA specifically interacts with FtsN and is sufficient for FtsA-FtsN interaction.

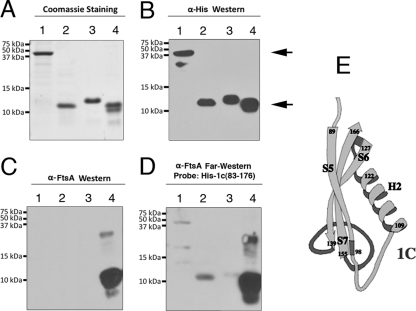

To confirm that this interaction is direct, we purified His6-FtsA-1c containing residues 83 to 176 to homogeneity (Fig. 6A, lane 4) and used it to probe blots containing FtsN or FtsNCyto derivatives in far-Western experiments. As shown in Fig. 6A to D, His6-FtsA-1c-83-176 interacted with FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG (lanes 2) but interacted only weakly with an equivalent amount of FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG (lanes 3). The interaction with full-length His6-FtsN-FLAG was variable and often weaker (lanes 1) than that with FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG, possibly because there were fewer molecules of the latter after equalizing for mass. Nonetheless, the data suggest that the 1c subdomain, like full-length FtsA, is sufficient to bind to a dimerized FtsNCyto protein.

Fig 6.

FtsA-1c-83-176 binding to FtsN and to FtsNCyto. Combined Western (B and C) and far-Western (D) results show binding of purified His6-FtsA-1c-83-176, used to probe membranes containing His6-FtsN-FLAG (lane 1, upper arrow, in panel B), His6-FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG (lane 2, lower arrow, in panel B), His6-FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG (lane 3), or His6-FtsA-1c-83-176 (lane 4), transferred from SDS-PAGE gels. The lower band in panel B, lane 1, is a degradation product that is also visible in panel A, lane 1. Panel A shows loading and protein purity controls after SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Molecular mass markers are shown to the left of each panel. The membrane in panel B was incubated with anti-His antibody, and those in panels C and D were incubated with anti-FtsA. The upper band in panels C and D, lanes 4, may be a trace contaminant in the FtsA-1c-83-176 preparation recognized only by the anti-FtsA antibody. The four gels were loaded and run identically, and the reaction conditions are described in Materials and Methods. (E) Cartoon diagram of the FtsA 1c subdomain (residues 83 to 176), containing alpha helix H2 and beta strands S5, S6, and S7, from the T. maritima structure (53).

Since the 1c subdomain is fairly large, with one alpha helix (H2) and three beta strands (S5, S6, and S7), as determined from the Thermotoga maritima crystal structure (53) (Fig. 6E), we also purified a truncated version that contained only residues 81 to 140 (His6-GluGlu-FtsA-1c-81-140), which removes 36 residues at the C-terminal portion of the domain, including the S7 beta strand and the loop connecting it to the S6 beta strand. We found that this truncated domain, like the full-length domain, interacted with full-length FtsN and FtsNCyto-ParLeu-FLAG but, again, interacted only weakly with FtsNCyto-AntiLeu-FLAG (data not shown). This confirms that this interaction is reproducible, suggests that only 60 amino acids (residues 81 to 140) of the FtsA 1c subdomain are needed for FtsA to bind to the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN, and supports the binding data for the longer version of subdomain 1c.

Excess His6-FtsNCyto-TM inhibits cell division.

Although FtsNCyto-TM is dispensable for FtsN function in vivo, we reasoned that overproduction of this segment of FtsN might exert a dominant-negative effect on cell division. We cloned His6-FtsNCyto-TM into pBAD33, which provides induction of gene expression by arabinose. Uninduced wild-type WM1074 cells containing pBAD33-His6-FtsNCyto-TM or pBAD33-His6-FtsN were short and indistinguishable from cells with pBAD33 or no plasmid. However, after 0.2% arabinose induction for several generations, cells expressing His6-FtsNCyto-TM or His6-FtsN became moderately filamentous, to approximately the same degree (Fig. 7A to D). Although strains with pBAD33, pBAD33-His6-FtsNCyto-TM, or pBAD33-His6-FtsN all formed colonies on LB agar plates supplemented with 0.2% arabinose, colonies expressing His6-FtsNCyto-TM were wrinkled (Fig. 7F). This morphotype indicates that a colony contains a significant proportion of nondividing cells (30). Colonies expressing full-length FtsN did not appear significantly different from control colonies (Fig. 7E and G), perhaps because the effect of full-length FtsN was less severe on solid medium. Taking into account the cell length data, these results indicate that cell division is modestly inhibited by overproduction of full-length FtsN, consistent with previous data indicating that overproduction of FtsN delays divisome constriction (1), and suggest that this effect is mediated largely by FtsNCyto-TM itself.

Fig 7.

Overproduction phenotypes of FtsN and FtsNCyto-TM. (A) Histogram of length distributions of cells with pBAD33 (WM4049), pBAD33-FtsNCyto-TM (WM4050), or pBAD33-FtsN (WM4051) after induction of expression with 0.2% arabinose for 2 h. Data were obtained from two independent experiments. (B to D) Representative micrographs obtained for the cells quantified in panel A. (B) pBAD33 vector (WM4049); (C) FtsNCyto-TM (WM4050); (D) FtsN (WM4051). Bar = 5 μm. Colony morphotypes shown in panels E, F, and G depict the typical phenotypes observed for the strains represented in panels B, C, and D, respectively, when cells were spot diluted onto LB agar plates containing 0.2% arabinose.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that the early divisome protein FtsA and the last essential divisome protein to localize to midcell, FtsN, interact directly. Our laboratory initially provided in vivo evidence of FtsA-FtsN interaction by using the DivIVA polar recruitment assay (11). Using this method, we observed polar recruitment of GFP-FtsN by molecules of FtsA that were fused to DivIVA, a Bacillus subtilis protein that localizes to E. coli cell poles. In vivo interaction between FtsA and FtsN was further supported by BACTH studies (36). Because the DivIVA and BACTH assays are unable to differentiate between direct and indirect protein-protein interactions, we utilized in vitro techniques to investigate FtsA-FtsN interaction further.

The involvement of the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN in FtsA-FtsN interaction is entirely consistent with the topology of each protein. FtsA is located exclusively in the cytoplasm, associating only peripherally with the inner membrane, via its MTS. FtsN, on the other hand, resides mostly in the periplasm, exposing only a small portion of the protein to the cytoplasm of the cell. To our knowledge, this is the first instance of a cytoplasmic domain of a bitopic divisome protein with a biochemically demonstrated interaction with another divisome protein.

Our data also suggest that the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN must form a dimer or multimer to interact with FtsA. FtsN self-interaction has been suggested by BACTH analysis and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) activity in previous studies (3, 36). Although FtsNCyto did not interact with FtsA unless it was fused to a parallel leucine zipper, FtsNCyto-TM did interact with FtsA in membrane-containing crude extracts. This, along with the positive interaction between FtsN1-54-′PhoA and FtsN in BACTH assays, suggests that the transmembrane domain of FtsN helps to mediate FtsN self-interaction.

We also showed that the 1c subdomain of FtsA is sufficient to bind to FtsN. The 1c subdomain was previously implicated in FtsA-FtsN interaction by use of the DivIVA polar recruitment assay, because GFP-FtsN could be recruited to cell poles by fusion of subdomain 1c directly to DivIVA (11). Like FtsN, FtsA has been shown to interact with itself (36, 45, 48, 51, 60). It has been postulated that the 1c subdomain of FtsA constitutes a portion of the FtsA-FtsA interface (10). If the 1c subdomain of FtsA is indeed involved in FtsA self-interaction, then it is possible that FtsN binding to subdomain 1c could compete with this self-interaction. Our previous results suggest that decreased FtsA-FtsA interaction correlates with increased cell division inhibition by FtsA (51). Therefore, one possibility is that overproduced FtsNCyto-TM may inhibit FtsA self-interaction mediated by the 1c subdomain. This would inhibit cell division and make FtsA more toxic (i.e., mimic an FtsA mutant defective in self-interaction). However, other explanations are also possible, including altering the interactions of other late divisome proteins, such as FtsI, with the 1c subdomain, which could alter FtsA activity.

A conserved patch of basic residues is located at positions 16 through 19 of FtsN (Fig. 4F). Because replacement of these residues with acidic amino acids greatly reduced the interaction with FtsA, we speculate that this conserved basic patch in FtsN is crucial for direct interaction with a segment of subdomain 1c of FtsA. Although it is tempting to speculate that FtsN and FtsA interact electrostatically, we cannot rule out the possibility that mutation of the basic patch in FtsN disturbs a secondary structure of FtsN that is required for FtsA-FtsN interaction.

PilM, a component of type IV pili, is a structural homolog of FtsA, and like FtsA, it is a cytoplasmic protein associated with the inner membrane as part of a complex with transmembrane proteins (38). One of these transmembrane proteins, PilN, inserts its short cytoplasmic domain into the cleft between domains 1A and 1C of PilM, as shown by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies (38). Since the E124A mutation of FtsA suppresses the loss of FtsN and is located at the analogous cleft in FtsA, we speculate that the cytoplasmic domain of FtsN, possibly involving the RRKK motif, may contact subdomain 1c at or near the cleft. Defining the binding interface between FtsN and FtsA will clearly require detailed structural studies.

It has been hypothesized that FtsN helps to trigger septation in a dividing E. coli cell (11, 39). FtsN is well positioned to serve this role because it is the last essential divisome protein to localize to the site of division, requiring a number of proteins downstream of FtsA in the pathway for its recruitment. In addition, FtsN is required to recruit amidases that commence degradation of septal peptidoglycan (2, 6, 43, 52). FtsN also indirectly recruits the Tol-Pal complex, which is involved in invagination of the outer membrane (5, 25). Like FtsN, FtsA may also act as a trigger for septation, as it has been shown to influence both the assembly and disassembly of FtsZ polymers (7, 23, 35), which would potentially allow FtsA-mediated constriction of the Z ring following interaction with FtsN.

Our working model, then, is that after FtsN is recruited to the divisome by multiple proteins and by self-enhanced localization (24), FtsN dimers are formed which can then bind directly to subdomain 1c of FtsA. Other divisome proteins, such as FtsI, may also bind to this portion of FtsA (11) and possibly compete for binding. Since FtsA binds directly to FtsZ, probably via FtsA's 2B subdomain (44), we postulate that this interaction then helps to transduce a signal to FtsZ polymers that coordinates Z ring constriction with septal murein synthesis activities. The cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains of FtsN can be replaced by heterologous cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains, although FtsNCyto may have a role in restoring some cell division activity in the absence of FtsK (18, 22, 31). To potentially explain why the FtsA-FtsN interaction seems to be dispensable for cell division, we favor the idea that the interaction between FtsA and FtsN provides one of several redundant Z ring constriction signals (43). Indeed, recent in vivo data implicate an interaction between FtsN and ZapA (3), between FtsN and ZipA (49), and between amidases and FtsZ via FtsEX (12, 58). Having such redundant triggers would ensure robust and timely constriction of the Z ring and is consistent with our model that the divisome is overbuilt.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank present and past members of the Margolin lab for helpful discussions and the T. Koehler and P. Christie labs for plasmids.

This work was supported by NIGMS grant 61074 and a grant from the Human Frontier Science Program.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 February 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aarsman ME, et al. 2005. Maturation of the Escherichia coli divisome occurs in two steps. Mol. Microbiol. 55: 1631– 1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Addinall SG, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. 1997. FtsN, a late recruit to the septum in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 25: 303– 309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alexeeva S, Gadella TW, Jr, Verheul J, Verhoeven GS, den Blaauwen T. 2010. Direct interactions of early and late assembling division proteins in Escherichia coli cells resolved by FRET. Mol. Microbiol. 77: 384– 398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arends SJ, et al. 2010. Discovery and characterization of three new Escherichia coli septal ring proteins that contain a SPOR domain: DamX, DedD, and RlpA. J. Bacteriol. 192: 242– 255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernard CS, Sadasivam M, Shiomi D, Margolin W. 2007. An altered FtsA can compensate for the loss of essential cell division protein FtsN in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 64: 1289– 1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. 2003. The Escherichia coli amidase AmiC is a periplasmic septal ring component exported via the twin-arginine transport pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 48: 1171– 1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beuria TK, et al. 2009. Adenine nucleotide-dependent regulation of assembly of bacterial tubulin-like FtsZ by a hypermorph of bacterial actin-like FtsA. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 14079– 14086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. 1991. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature 354: 161– 164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burgess RR, Arthur TM, Pietz BC. 2000. Mapping protein-protein interaction domains using ordered fragment ladder far-Western analysis of hexahistidine-tagged fusion proteins. Methods Enzymol. 328: 141– 157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carettoni D, et al. 2003. Phage-display and correlated mutations identify an essential region of subdomain 1C involved in homodimerization of Escherichia coli FtsA. Proteins 50: 192– 206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corbin BD, Geissler B, Sadasivam M, Margolin W. 2004. A Z-ring-independent interaction between a subdomain of FtsA and late septation proteins as revealed by a polar recruitment assay. J. Bacteriol. 186: 7736– 7744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corbin BD, Wang Y, Beuria TK, Margolin W. 2007. Interaction between cell division proteins FtsE and FtsZ. J. Bacteriol. 189: 3026– 3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dai K, Xu Y, Lutkenhaus J. 1993. Cloning and characterization of ftsN, an essential cell division gene in Escherichia coli isolated as a multicopy suppressor of ftsA12(Ts). J. Bacteriol. 175: 3790– 3797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dai K, Xu Y, Lutkenhaus J. 1996. Topological characterization of the essential Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsN. J. Bacteriol. 178: 1328– 1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Datta P, Dasgupta A, Bhakta S, Basu J. 2002. Interaction between FtsZ and FtsW of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 24983– 24987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Den Blaauwen T, Buddelmeijer N, Aarsman ME, Hameete CM, Nanninga N. 1999. Timing of FtsZ assembly in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181: 5167– 5175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Di Lallo G, Fagioli M, Barionovi D, Ghelardini P, Paolozzi L. 2003. Use of a two-hybrid assay to study the assembly of a complex multicomponent protein machinery: bacterial septosome differentiation. Microbiology 149: 3353– 3359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Draper GC, McLennan N, Begg K, Masters M, Donachie WD. 1998. Only the N-terminal domain of FtsK functions in cell division. J. Bacteriol. 180: 4621– 4627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eraso JM, Kaplan S. 2002. Redox flow as an instrument of gene regulation. Methods Enzymol. 348: 216– 229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erickson HP. 1997. FtsZ, a tubulin homologue in prokaryote division. Trends Cell Biol. 7: 362– 367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Geissler B, Elraheb D, Margolin W. 2003. A gain of function mutation in ftsA bypasses the requirement for the essential cell division gene zipA in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100: 4197– 4202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geissler B, Margolin W. 2005. Evidence for functional overlap among multiple bacterial cell division proteins: compensating for the loss of FtsK. Mol. Microbiol. 58: 596– 612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geissler B, Shiomi D, Margolin W. 2007. The ftsA* gain-of-function allele of Escherichia coli and its effects on the stability and dynamics of the Z ring. Microbiology 153: 814– 825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gerding MA, et al. 2009. Self-enhanced accumulation of FtsN at division sites and roles for other proteins with a SPOR domain (DamX, DedD, and RlpA) in Escherichia coli cell constriction. J. Bacteriol. 191: 7383– 7401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gerding MA, Ogata Y, Pecora ND, Niki H, de Boer PA. 2007. The trans-envelope Tol-Pal complex is part of the cell division machinery and required for proper outer-membrane invagination during cell constriction in E. coli. Mol. Microbiol. 63: 1008– 1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Godsey MH, Baranova NN, Neyfakh AA, Brennan RG. 2001. Crystal structure of MtaN, a global multidrug transporter gene activator. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 47178– 47184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goehring NW, Beckwith J. 2005. Diverse paths to midcell: assembly of the bacterial cell division machinery. Curr. Biol. 15: 514– 526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goehring NW, Gonzalez MD, Beckwith J. 2006. Premature targeting of cell division proteins to midcell reveals hierarchies of protein interactions involved in divisome assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 61: 33– 45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goehring NW, Gueiros-Filho F, Beckwith J. 2005. Premature targeting of a cell division protein to midcell allows dissection of divisome assembly in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 19: 127– 137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goehring NW, Petrovska I, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 2007. Mutants, suppressors, and wrinkled colonies: mutant alleles of the cell division gene ftsQ point to functional domains in FtsQ and a role for domain 1C of FtsA in divisome assembly. J. Bacteriol. 189: 633– 645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goehring NW, Robichon C, Beckwith J. 2007. A role for the non-essential N-terminus of FtsN in divisome assembly. J. Bacteriol. 189: 646– 649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grussenmeyer T, Scheidtmann KH, Hutchinson MA, Eckhart W, Walter G. 1985. Complexes of polyoma virus medium T antigen and cellular proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82: 7952– 7954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177: 4121– 4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hu JC, O'Shea EK, Kim PS, Sauer RT. 1990. Sequence requirements for coiled-coils: analysis with lambda repressor-GCN4 leucine zipper fusions. Science 250: 1400– 1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jensen SO, Thompson LS, Harry EJ. 2005. Cell division in Bacillus subtilis: FtsZ and FtsA association is Z-ring independent, and FtsA is required for efficient midcell Z-ring assembly. J. Bacteriol. 187: 6536– 6544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Karimova G, Dautin N, Ladant D. 2005. Interaction network among Escherichia coli membrane proteins involved in cell division as revealed by bacterial two-hybrid analysis. J. Bacteriol. 187: 2233– 2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. 1998. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95: 5752– 5756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karuppiah V, Derrick JP. 2011. Structure of the PilM-PilN inner membrane type IV pilus biogenesis complex from Thermus thermophilus. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 24434– 24442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lutkenhaus J. 2009. FtsN—trigger for septation. J. Bacteriol. 191: 7381– 7392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ma X, Ehrhardt DW, Margolin W. 1996. Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93: 12998– 13003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ma X, Margolin W. 1999. Genetic and functional analyses of the conserved C-terminal core domain of Escherichia coli FtsZ. J. Bacteriol. 181: 7531– 7544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Meng FG, Zeng X, Hong YK, Zhou HM. 2001. Dissociation and unfolding of GCN4 leucine zipper in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate. Biochimie 83: 953– 956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peters NT, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. 2011. A fail-safe mechanism in the septal ring assembly pathway generated by the sequential recruitment of cell separation amidases and their activators. J. Bacteriol. 193: 4973– 4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. 2007. Identification of a region of FtsA required for interaction with FtsZ. Mol. Microbiol. 64: 1129– 1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. 2005. Tethering the Z ring to the membrane through a conserved membrane targeting sequence in FtsA. Mol. Microbiol. 55: 1722– 1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pichoff S, Lutkenhaus J. 2002. Unique and overlapping roles for ZipA and FtsA in septal ring assembly in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 21: 685– 693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Raychaudhuri D. 1999. ZipA is a MAP-Tau homolog and is essential for structural integrity of the cytokinetic FtsZ ring during bacterial cell division. EMBO J. 18: 2372– 2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rico AI, Garcia-Ovalle M, Mingorance J, Vicente M. 2004. Role of two essential domains of Escherichia coli FtsA in localization and progression of the division ring. Mol. Microbiol. 53: 1359– 1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rico AI, Garcia-Ovalle M, Palacios P, Casanova M, Vicente M. 2010. Role of Escherichia coli FtsN protein in the assembly and stability of the cell division ring. Mol. Microbiol. 76: 760– 771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shiomi D, Margolin W. 2008. Compensation for the loss of the conserved membrane targeting sequence of FtsA provides new insights into its function. Mol. Microbiol. 67: 558– 569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shiomi D, Margolin W. 2007. Dimerization or oligomerization of the actin-like FtsA protein enhances the integrity of the cytokinetic Z ring. Mol. Microbiol. 66: 1396– 1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Uehara T, Parzych KR, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. 2010. Daughter cell separation is controlled by cytokinetic ring-activated cell wall hydrolysis. EMBO J. 29: 1412– 1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. van den Ent F, Lowe J. 2000. Crystal structure of the cell division protein FtsA from Thermotoga maritima EMBO J. 19: 5300– 5307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vicente M, Rico AI. 2006. The order of the ring: assembly of Escherichia coli cell division components. Mol. Microbiol. 61: 5– 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weiss DS, Chen JC, Ghigo JM, Boyd D, Beckwith J. 1999. Localization of FtsI (PBP3) to the septal ring requires its membrane anchor, the Z ring, FtsA, FtsQ, and FtsL. J. Bacteriol. 181: 508– 520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weiss DS, et al. 1997. Localization of the Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsI (PBP3) to the division site and cell pole. Mol. Microbiol. 25: 671– 681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wissel MC, Weiss DS. 2004. Genetic analysis of the cell division protein FtsI (PBP3): amino acid substitutions that impair septal localization of FtsI and recruitment of FtsN. J. Bacteriol. 186: 490– 502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang DC, et al. 2011. An ATP-binding cassette transporter-like complex governs cell-wall hydrolysis at the bacterial cytokinetic ring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108: E1052– E1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang JC, Van Den Ent F, Neuhaus D, Brevier J, Lowe J. 2004. Solution structure and domain architecture of the divisome protein FtsN. Mol. Microbiol. 52: 651– 660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yim L, et al. 2000. Role of the carboxy terminus of Escherichia coli FtsA in self-interaction and cell division. J. Bacteriol. 182: 6366– 6373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.