Abstract

The utility of sequencing a second highly variable locus in addition to the spa gene (e.g., double-locus sequence typing [DLST]) was investigated to overcome limitations of a Staphylococcus aureus single-locus typing method. Although adding a second locus seemed to increase discriminatory power, it was not sufficient to definitively infer evolutionary relationships within a single multilocus sequence type (ST-5).

TEXT

Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus is commonly used for identification of putative transmissions among patients as well as for surveillance of both local and international clones. In such a context, sequence analysis of the repeat region of the spa gene is extensively used for typing S. aureus isolates (i.e., spa typing) (5). Yet recent studies investigating the evolutionary history of single S. aureus sequence types (STs) using high-throughput sequencing data highlighted that spa typing may occasionally reflect homoplasies (6, 9). Homoplasies are similarities in character states for reasons other than inheritance from a common ancestor and might have serious consequences for interpreting S. aureus typing data. For example, homoplasies can misleadingly indicate transmission between unrelated patients (11) or misleadingly suggest the global spread of individual local clones (9). One way to get around ambiguities created by homoplasies is to add other independent markers to the spa gene. This approach has, for example, been used in the double-locus sequence typing (DLST) method, for which partial sequences of the repeat regions of both clfB and spa genes are combined (8). In this study, we aimed to investigate the utility of adding a second locus to the spa gene to overcome the limitations of a single-locus typing method. For this reason, we analyzed a collection of 127 international S. aureus isolates belonging to ST-5 with DLST. These isolates had previously been sorted into at least 14 phylogenetic lineages on the basis of genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and they showed 19 different spa types (9). Among the nine spa types shared by at least two isolates, six were found in multiple unrelated haplotypes and/or lineages, suggesting homoplasies (9).

To determine the DLST types of the 127 ST-5 isolates, we sequenced approximately 500 bp from each of the clfB and spa genes as already described (2, 8). It is important to note that although spa typing and DLST-spa investigate polymorphisms in the same repeat region of the spa gene, the methods do not analyze exactly the same sequences. Whereas spa typing analyzes the entire repeat region, DLST-spa investigates only ca. 500 bp of the same region. Therefore, the spa alleles of these two methods are not identical. A table of correspondence between the two categories of alleles can be found in reference 2. Thirty-six DLST-clfB alleles and 25 DLST-spa alleles were observed for the 127 isolates. In a first step, these alleles were mapped on the minimum spanning tree of these isolates that is based on the 156 SNPs assessed in reference 9 (Fig. 1A and B). Similarly to reference 9, an allele was considered homoplasious when it occurred simultaneously in haplotypes that were unrelated based on the minimum spanning tree, suggesting that it emerged several times independently. This is a valid approach because the SNP-based tree was almost unique, as there were almost no homoplasies among SNPs (homoplasy index, 0.04) (9). In addition, several methods were used to identify homoplasies on more statistically robust grounds.

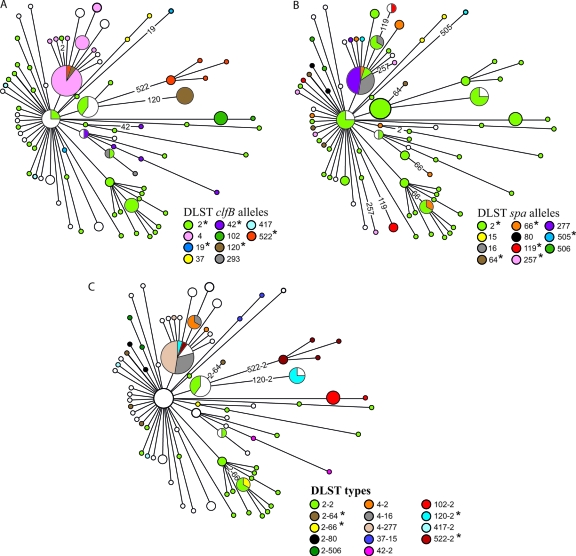

Fig 1.

Minimum spanning tree of ST-5 isolates based on the 156 SNPs assessed in reference 9. Colors indicate the DLST-clfB (A) and DLST-spa (B) alleles as well as the DLST types (C) occurring in more than one haplotype. The emergence of spa, clfB, and DLST types that occurred elsewhere in the tree are labeled with the allele or type number, and homoplasious alleles are indicated by an asterisk.

Among the 10 DLST-clfB alleles and 11 DLST-spa alleles that occurred in more than one haplotype on the minimum spanning tree, 5 and 6, respectively, occurred in unrelated haplotypes and represented potential homoplasies (asterisks in Fig. 1A and B). Combining both genes into DLST gives a total of 58 DLST types, confirming the higher discriminatory power of this method. Among the 14 DLST types that occurred in at least two haplotypes, 4 occurred in unrelated haplotypes and represented potential homoplasies (asterisks in Fig. 1C). This proportion is not significantly different than that with single-gene typing (4/14 versus 5/10 and 6/11), though the small sample sizes preclude a meaningful statistical analysis of proportions. The potentially homoplasious DLST types were in all cases composed of a homoplasious allele at one locus in combination with the ancestral allele at the other locus (i.e., either clfB allele 2 and a spa allele other than spa allele 2, repectively, or a clfB allele other than clfB allele 2 and spa allele 2, respectively). The stability of ancestral alleles is supported by the observation that for both loci, the respective ancestral type was shared by most lineages. A recent study showed that several strains isolated 2 to 3 decades apart in different parts of the world shared identical DLST-spa alleles (1).

Maximum-parsimony phylogenetic analysis globally showed the same picture as the minimum spanning tree, although the support for branching order (i.e., bootstrap values) was relatively low. Bootstrapping (and other resampling methods) provides low support for short branches in general because it is based on drawing subsamples from the alignment in such a way that some SNPs are not represented in some of the resulting alignments and trees.

Another method to identify homoplasies is to look for alleles occurring simultaneously in two different haplotypes, as described in reference 13 (i.e., 4-gamete test). In our data set, only DLST-spa alleles 2 and 66 and 2 and 16 were in this situation, suggesting that these alleles or their haplotypes were homoplasious. In contrast to DLST-spa, no shared DLST-clfB alleles or DLST types occurred simultaneously in two different haplotypes, suggesting that adding the clfB gene might overcome spa homoplasies. However, this approach is relatively conservative, since it requires having haplotypes with shared alleles, and not all the homoplasies will be identified by this method (7).

To further take into account phylogenetic uncertainty, we used a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach (10). We calculated the association index (AI), parsimony score (PS), and maximum monophyletic clade (MC) statistics, which are correlated with the strength of the phylogeny-trait association, for each allele/type of each typing method with BaTS v1.0 (10). This software provides significance estimation while accounting for uncertainty by the use of posterior sets of trees obtained through earlier Bayesian MCMC analyses. MCMC analyses were performed using BEAST v.1.6.0 (3) for 108 generations, with tree sampling every 105 generations. For BaTS analyses, the first 10 of the 1,000 sampled trees were discarded as burn-in and 200 randomizations were performed to estimate the null distributions for the AI, PS, and MC statistics (10). For each typing method (DLST-clfB, DLST-spa, and DLST), the MC analyses identified several alleles without significant association with the SNP-based phylogeny (P > 0.05) (Table 1), including DLST-clfB alleles 19, 293, and 417, DLST-spa alleles 257, 277, and 505, and DLST types 2-66, 4-2, 4-16, 417-2, and 4-277. The proportions of these homoplasious alleles among those occurring in more than one haplotype were 3/10 (30%) for DLST-clfB, 3/11 (27%) for DLST-spa, and 5/14 (36%) for DLST. Hence, sequencing a second locus did not reduce the proportion of homoplasious alleles. Moreover, the AI and PS statistics detected a significant association between trait and phylogeny, indicating that the potential homoplasies in each method did not affect the overall association between alleles and phylogeny.

Table 1.

Values of the allelic MC and overall AI and PS statistics for each DLST-clfB and DLST-spa allele and each DLST type occurring in more than one SNP-based haplotype

| Typing method and allele or typea | MC value | AI | PS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLST-clfB | 5.1 | 42.4 | ||

| 2 | 15.17 | 0.00499 | ||

| 4 | 6.14 | 0.00499 | ||

| 19* | 1.00 | 1 | ||

| 37 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 42 | 3.98 | 0.00499 | ||

| 102 | 5.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 120 | 3.87 | 0.00499 | ||

| 293* | 1.20 | 1 | ||

| 417* | 1.02 | 1 | ||

| 522 | 5.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| DLST-spa | 6.7 | 47.3 | ||

| 2 | 7.36 | 0.00499 | ||

| 15 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 16 | 1.59 | 0.01999 | ||

| 64 | 2.04 | 0.019 | ||

| 66 | 2.01 | 0.02999 | ||

| 80 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 119 | 2.00 | 0.0099 | ||

| 257* | 1.01 | 1 | ||

| 277* | 2.02 | 0.0899 | ||

| 505* | 1.00 | 1 | ||

| 506 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| DLST | 8.5 | 69.3 | ||

| 2-64 | 2.04 | 0.01999 | ||

| 2-66* | 1.00 | 1 | ||

| 2-80 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 2-2 | 7.16 | 0.00499 | ||

| 4-2* | 1.29 | 1 | ||

| 4-16* | 1.42 | 1 | ||

| 102-2 | 5.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 120-2 | 1.83 | 0.0099999 | ||

| 2-506 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 37-15 | 2.00 | 0.00499 | ||

| 417-2* | 1.02 | 1 | ||

| 42-2 | 1.98 | 0.00499 | ||

| 4-277* | 2.02 | 0.07999 | ||

| 522-2 | 5.00 | 0.00499 |

Alleles/types with no significant association with SNP-based phylogeny (P > 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk.

The existence of identical clfB or spa alleles in unrelated haplotypes is likely explained by the particular mutation patterns of these loci, which mostly diversify through duplication and/or deletion of repeat units (4, 12). In this situation, it is not surprising to encounter the same configuration of the repeat several times during its evolution. Homoplasies do not seem to be frequent among clonal complexes (CCs), since most of the DLST-clfB or DLST-spa alleles are specific to CCs (1). Although homoplasy seems to be common within ST-5, the extent of this phenomenon remains to be tested for other sequence types. A recent analysis of multiple ST-239 genomes highlighted only one homoplasy with spa typing (6), and the analyses of other clonal lineages will have to await the availability of high-resolution phylogenetic reconstructions.

In conclusion, adding a second highly variable locus to the spa gene (DLST) seemed to increase the discrimination of types. However, the high proportion of ancestral alleles caused the sequencing of an additional locus to be insufficient for determining definite inference of evolutionary relationships within a single multilocus sequence type.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Coombs, H. de Lencastre, R. V. Goering, M. Ip, A. O. Shittu, R. L. Skov, M. Struelens, Y. C. Wand, W. Wannet, and H. Westh for providing us with the methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains, Annette Weller for technical assistance, Agnès Horn for PAUP analyses, and Valérie Vogel for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Basset P, et al. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus clfB and spa alleles of the repeat regions are segregated into major phylogenetic lineages. Infect. Genet. Evol. 9:941–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basset P, et al. 2010. Usefulness of double locus sequence typing (DLST) for regional and international epidemiological surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1289–1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drummond A, Rambaut A. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frenay HM, et al. 1996. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 15:60–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grundmann H, et al. 2010. Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 7:e1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harris SR, et al. 2010. Evolution of MRSA during hospital transmission and intercontinental spread. Science 327:469–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hudson RR, Kaplan NL. 1985. Statistical properties of the number of recombination events in the history of a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics 111:147–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuhn G, Francioli P, Blanc DS. 2007. Double-locus sequence typing using clfB and spa, a fast and simple method for epidemiological typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:54–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nübel U, et al. 2008. Frequent emergence and limited geographic dispersal of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:14130–14135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parker J, Rambaut A, Pybus OG. 2008. Correlating viral phenotypes with phylogeny: accounting for phylogenetic uncertainty. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8:239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Senn L, et al. 2011. Investigation of classical epidemiological links between patients harbouring identical, non-predominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotypes and lessons for epidemiological tracking. J. Hosp. Infect. 79:202–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shopsin B, et al. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3556–3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smyth DS, et al. 2010. Population structure of a hybrid clonal group of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, ST239-MRSA-III. PLoS One 5:e8582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]