Abstract

Human telomeres are DNA-protein complexes that cap and protect the ends of chromosomes. The protein PinX1 associates with telomeres through an interaction with the resident double-stranded telomere-binding protein TRF1. PinX1 also binds to and inhibits telomerase, the enzyme responsible for complete replication of telomeric DNA. We now report that endogenous PinX1 associates with telomeres primarily at mitosis. Moreover, knockdown of PinX1 caused delayed mitotic entry and reduced the accumulation of TRF1 on telomeres during this stage of the cell cycle. Taking these findings together, we suggest that one function of PinX1 is to stabilize TRF1 during mitosis, perhaps to promote transition into M phase of the cell cycle.

INTRODUCTION

Human telomeres are DNA-protein complexes that cap and protect the ends of chromosomes. The proteins TRF1, TRF2, and POT1 bind directly to telomeric DNA and serve as anchors for an array of telomere-associated proteins that localize to telomeres through protein-protein interactions (20). TRF1 is a resident double-stranded telomere DNA-binding protein found throughout telomere chromatin (7, 20). Overexpression of TRF1 in human cells causes telomere shortening (25). Conversely, while knockout of the Trf1 gene in mice is embryonic lethal (12), conditional inactivation of TRF1 results in DNA damage at telomeres and promotes carcinogenesis (16, 19, 21). Thus, TRF1 is important for regulation of telomere length and stability.

In a yeast two-hybrid screen using human TRF1 as bait, the protein PinX1 was identified as a novel TRF1-binding protein (33). Human PinX1 has an N-terminal glycine-rich domain (G-patch domain) shared among RNA binding proteins and a C-terminal TRF1-binding motif (FXLXP) (6, 33). Ectopic PinX1 colocalizes with ectopic TRF1 (33) and increases the amount of TRF1 on telomeres (29). PinX1 also associates with both the RNA (2) and protein (2, 33) subunits of telomerase, the enzyme responsible for complete replication of telomeres (15). Moreover, ectopic PinX1 inhibits telomerase activity (33), whereas PinX1+/− mice exhibit increased telomerase activity (32). As such, PinX1 was suggested to play a role in regulating telomerase (32, 33).

Recent studies suggest that the PinX1 function may extend beyond this role. Notably, ectopic PinX1 is also found in the nucleolus during most of the cell cycle, but during mitosis, the protein concentrates on the outer plate of kinetochores and the periphery of chromosomes (30). Furthermore, PinX1+/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) display anaphase bridges during cell division, even though the cells have long telomeres (32). Given these findings, we determined when endogenous PinX1 associates with telomeres, which uncovered a novel role for PinX1 in stabilizing TRF1 at mitosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Knockdown of PinX1.

HeLa cells were transiently transfected with 20 nM scrambled control (5′-GUUUAUCAGCACUCGGUUGACUAGA-3′), small interfering RNA (siRNA) PinX1-1 (5′-CCAGUAGAGAUAGCAGAGGACGCUA-3′), or siRNA PinX1-2 (5′-ACUGGAUUGCCCAUCAGGAUGAUUU-3′) oligonucleotide (Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine 2000 or Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Twelve hours later, cells were expanded, and 48 h later, lysates were collected for immunoblotting.

Immunoblot analysis of endogenous proteins.

To detect endogenous PinX1, phospho-histone H3, and β-tubulin, cell lysates were immunoblotted with an anti-PinX1 antibody (derived from affinity-purified antibodies from rabbits immunized with the human PinX1 peptide encompassing amino acids 215 to 233) at a 1:1,000 dilution, an anti-phospho-(Ser10) histone H3 antibody (Cell Signaling) at a 1:1,000 dilution, and an antitubulin antibody (Sigma) at a 1:2,000 dilution, as previously described (1, 26).

ChIP assay.

HeLa cells transiently transfected with scrambled or PinX1 siRNA were cultured for 48 h and then left untreated, synchronized by double thymidine block (27), or arrested at mitosis with nocodazole (18). Untreated (primarily interphase) cells, cells at various time points after release from the double thymidine block, or cells collected after nocodazole treatment by the mitotic shake-off method were lysed, and 1 mg of protein extract was used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with 4 μg of the aforementioned anti-PinX1 antibody, anti-TRF1 antibody (10), or rabbit IgG antibody as a control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by a dot blot assay with a 32P-labeled (T2AG3)4 oligonucleotide or, as a control, Alu repeat probe using 5 μg of genomic DNA as previously described (3). In parallel, cell lysates were immunoblotted to detect phospho-histone H3, and in some cases, a fraction of cells was also assayed for cell cycle progression by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The percentage of telomeric DNA precipitated by PinX1 antibody was quantitated by calculating the intensity of PinX1 hybridization using NIH ImageJ, which was subtracted from the hybridization signal of the IgG ChIP and divided by the hybridization signal of genomic DNA. Individual measurements or the means ± standard deviations (SD) of multiple measurements were plotted against time or cell cycle.

FACS.

HeLa cells treated or not treated with scrambled siRNA or siRNA PinX1-2 were synchronized by double thymidine block and collected at various time points. A portion of the cells was treated with a propidium iodide solution containing RNase A and sorted on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) with CellQuest software. Lysates prepared from the remaining cells were immunoblotted to detect phospho-histone H3 (see above).

Live-cell imaging.

HeLa cells stably transfected with pBabe-Puro-GFP-histone-H2B (Addgene) were transiently cotransfected with PinX1 or scrambled siRNA and the BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor Red fluorescent oligonucleotide (Invitrogen) to demark transfected cells, arrested in G1/S phase by double thymidine block as described above, and then released into G1/S phase. Seven hours 30 min later, 23 cells transfected (BLOCK-iT positive) with PinX1 or scrambled siRNA were monitored by live-cell imaging for a total of 17 h using an Olympus VivaView FL incubator microscope. Differential interference contrast (DIC) (cells) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (GFP-histone H2B) were monitored every 3 min, while red fluorescent protein (RFP) (BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor Red fluorescent oligonucleotide) was monitored every 30 min. Cells were considered to have begun mitosis when GFP-histone H2B-labeled chromosomes began to aggregate and to have completed mitosis when two daughter cells were completely separated (not shown).

Analysis of apoptosis.

HeLa cells were transiently transfected with PinX1 siRNA or scrambled siRNA, synchronized to G1/S phase by double thymidine block, and released into cell cycle as described above. Eight hours later, the cells were collected every hour for 5 h and immunoblotted with antitubulin, anti-phospho-histone H3, or anti-PinX1 antibodies as described above or the anti-cleaved-caspase 3 (Asp175) (5A1E) rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling) at a 1:1,000 dilution. Asynchronized HeLa cells transiently transfected with PinX1 or scrambled siRNA served as controls.

In vitro protein competition assay.

Amounts of 0.5 μg of bacterially produced recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST) (encoded by plasmid pGEX-6P-1; Amersham) or GST-TRF1 (encoded by plasmid pGEX-TRF1, derived from cloning the region corresponding to amino acids 4 to 1312 of human Myc-tagged TRF1 cDNA into plasmid pGEX-6P-1) were captured on glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham). These were incubated with both increasing concentrations (1, 5, and 10 μg) of bacterially produced and purified recombinant maltose binding protein (MBP) (encoded by plasmid pMAL-C2X; New England BioLabs) or MBP-PinX1 (encoded by plasmid pMAL-PinX1, derived from cloning the region corresponding to amino acids 2 to 984 of human FLAG-tagged PinX1 cDNA [2] into plasmid pMAL-C2X) and 5 μl of 35S-labeled TIN2 that was synthesized with the T7 quick-coupled TNT system (Promega) using plasmid pCIneo-myc-TIN2 (3). Similarly, 1 μg GST or GST-TRF1 protein was incubated with both increasing concentrations (1, 5, and 10 μg) of MBP or MBP-TIN2 (encoded by plasmid pMAL-TIN2, derived from cloning the region corresponding to amino acids 2 to 354 of human myc-tagged TIN2 cDNA into plasmid pMAL-C2X) and 5 μl of 35S-labeled PinX1 that was synthesized with the T7 quick-coupled TNT system (Promega) using plasmid pET28-PinX1. The total volume was brought to 1 ml with binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin [BSA], and protease inhibitors) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were then washed three times with binding buffer for 10 min, followed by SDS-PAGE and exposure on a phosphorimager screen. The intensities of the bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ.

Coimmunoprecipitation of PinX1 or TIN2 with TRF1.

293T cells were transiently transfected, using the Fugene 6 reagent (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions, with combinations of 8 μg of pCMV-Myc-TRF1 (derived from cloning human TRF1 cDNA into plasmid pCMV-Myc [Clontech]), pBabePuro-FLAG-PinX1 (17), and pCMV-HA-TIN2 (derived from cloning human TIN2 cDNA [3] into plasmid pCMV-HA [Clonetech]) as indicated below. Forty-eight hours later, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 10 μl of anti-FLAG M2–agarose (Sigma) or antihemagglutinin (anti-HA) affinity beads (Roche), followed by immunoblot assay with the antibodies anti-HA (Roche) at a 1:1,000 dilution, anti-Myc (Invitrogen) at a 1:5,000 dilution, anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) at a 1:1,000 dilution, or antitubulin (Sigma) at a 1:2,000 dilution, as described above and as previously described (11). The intensities of the bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ.

Coimmunoprecipitation of Fbx4 with TRF1.

293T cells were transiently transfected, using the Fugene 6 reagent (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions, with combinations of 0.5 μg of pCMV-Myc-TRF1, pCMV-HA-Fbx4 (derived from cloning a PCR-amplified human Fbx4 cDNA [OriGene] into plasmid pCMV-HA [Clontech]) and increasing amounts (0, 0.5, and 1.5 μg) of pBabePuro-FLAG-PinX1 as indicated below. Forty-eight hours later, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 10 μl of anti-HA affinity beads (Roche), followed by immunoblot assay as described above. The intensities of the bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ.

TRF1 stability assay.

HeLa cells were transiently cotransfected with pCMV-Myc-TRF1 (see above) encoding Myc-TRF1 and a scrambled control siRNA or PinX1-2 siRNA oligonucleotide as described above. Twelve hours later, cells were expanded and then, 48 h later, were either not treated or arrested with nocodazole for 12 h. Cells were collected (by the mitotic shake-off method in the case of nocodazole-treated cells), and the lysates immunoblotted with the aforementioned anti-PinX1, TRF415 (8), or antitubulin antibody. The intensities of the bands were quantified using NIH ImageJ.

RESULTS

Endogenous PinX1 accumulates on telomeres primarily during mitosis.

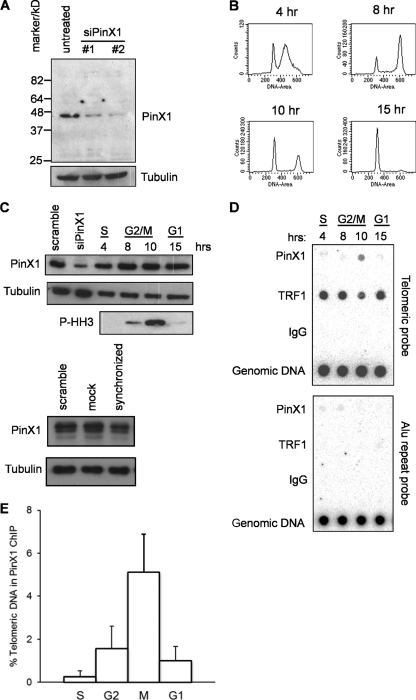

Ectopically expressed PinX1 has been found to localize to nucleoli, nucleoplasm, and telomeres when coexpressed with TRF1 (29, 30, 33). To analyze when endogenous human PinX1 associates with telomeres, we first generated an anti-PinX1 antibody, which typically recognizes a single band at approximately 45 kDa, the projected size of this protein, in an immunoblot assay. To further validate the specificity of this antibody, we demonstrate that this band is diminished by treatment with two independent siRNAs targeting PinX1 (Fig. 1A). Using this antibody, we analyzed the association of endogenous PinX1 with telomeres throughout the cell cycle by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. Specifically, HeLa cells were released from a double thymidine block, and lysates were collected at various stages of the cell cycle. S-phase cells were collected at 4 h, at which time a large fraction of the cells had a DNA content between 2n and 4n, as assessed by FACS analysis (Fig. 1B), and lacked the mitotic marker phospho-histone H3, as assessed by immunoblot assay (Fig. 1C). G2- to early-M-phase cells were collected at 8 h, at which time a large fraction of the cells had a 4n DNA content and low levels of phosphorylated histone H3. G2/M-phase and M-phase cells were collected at 10 h, at which time a large fraction of the cells had a 4n DNA content and high levels of phosphorylated histone H3. Finally, G1-phase cells were collected at 15 h, at which time a large fraction of the cells had a 2n DNA content and lacked phosphorylated histone H3 (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig 1.

PinX1 localizes at telomeres during M phase. (A) Levels of endogenous PinX1, as assessed by immunoblot assay with an anti-PinX1 antibody, in cells untreated or treated with two different PinX1 siRNAs. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. (B to D) HeLa cells were synchronized by double thymidine block, released, and collected at the four indicated time points. Collected cells were split into three portions that were stained with propidium iodide and subjected to FACS for cell cycle analysis (B), immunoblotted to detect endogenous PinX1, phospho-histone H3 (P-HH3) as a marker of mitosis, or tubulin as a loading control (as additional controls, PinX1 and tubulin levels were also analyzed in scrambled-siRNA-transfected cells, mock-transfected cells, or untransfected cells synchronized by double thymidine block) (C), or used for ChIP analysis with an anti-PinX1 antibody or an anti-TRF1 antibody or IgG as controls, followed by Southern hybridization with a telomere or control Alu probe (5 μg genomic DNA served as a hybridization control) (D). Data are representative of three replicate experiments. (E) Means ± SD of the normalized hybridization intensities of telomeric DNA coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous PinX1 from three independent ChIP experiments at the indicated cell cycle phases.

Telomeric chromatin associated with PinX1 was immunoprecipitated with the aforementioned anti-PinX1 antibody and detected by hybridization with a telomeric probe. Chromatin precipitation with an anti-TRF1 and an IgG antibody served as positive and negative controls, respectively. As expected, the TRF1 and IgG antibodies did and did not, respectively, coimmunoprecipitate telomeric chromatin throughout the cell cycle (Fig. 1D). The reduced signal in the TRF1 ChIP at the 10-h time point was only seen in this preparation. Unexpectedly, we did not detect an association of PinX1 with telomeric chromatin during any phase of the cell cycle except at the 10-h time point, corresponding primarily to M phase. This association was specific to telomeric chromatin, as PinX1 (and the positive control TRF1) did not coimmunoprecipitate with other repetitive (Alu) DNA (Fig. 1D). This M-phase association was also reproducible, as the same results were observed in three independent experiments (Fig. 1E). The absence of a ChIP signal in the other phases of the cell cycle was not due to reduced PinX1 protein levels, as demonstrated by immunoblotting with the aforementioned anti-PinX1 antibody, revealing roughly equivalent amounts of this protein with the exception of a slight decrease at S phase (Fig. 1C). Additionally, similar levels of PinX1 were detected in the controls that were treated with scrambled siRNA and mock transfected, although a slight decrease in PinX1 levels was detected in synchronized cells (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results indicate that PinX1 associates with telomeres primarily during mitosis.

PinX1 depletion causes delayed mitotic entry.

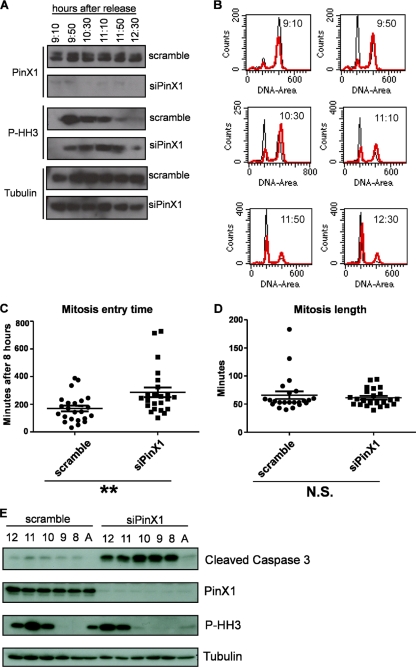

Since PinX1 associated with telomere chromatin at mitosis (Fig. 1) and RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated knockdown of PinX1 was recently reported to result in lagging chromosome segregation (30), we investigated the impact of depleting PinX1 during this phase of the cell cycle. Specifically, the human cell line HeLa was transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siRNA against PinX1, and then the cells were synchronized by double thymidine block, released, and after 9 h 10 min, cells were collected every 40 min for 4 h. Cell cycle progression was assessed by FACS analysis and immunoblot assay for phospho-histone H3. As noted above, PinX1 levels did not change appreciably during the cell cycle in scrambled siRNA-treated cells, while PinX1 siRNA-treated cells had little detectable PinX1 protein (Fig. 2A). Scrambled control cells entered M phase approximately 9 h 50 min after release, as evidenced by 4n DNA content and increased phosphorylated histone H3 levels. These cells had traversed through M phase and were primarily in G1 2 h later, as evidenced by the accumulation of cells with a 2n DNA content and an almost complete lack of detectable phosphorylated histone H3 protein (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, at the 9-h 50-min time point, most PinX1 siRNA-treated cells still had a high 4n DNA content and low phosphorylated histone H3 levels (Fig. 2A and B). This delay was not observed during the transition from S to G2 (not shown), suggesting an M-phase-specific defect. Although ectopic expression of an siRNA-resistant PinX1 protein did not reverse this M-phase defect, the same effect was observed in a total of five different experiments and with a second siRNA (not shown), arguing that the loss of PinX1 delays entry into and progression through M phase.

Fig 2.

Knockdown of PinX1 delays entry into mitosis. HeLa cells transfected with a scrambled control siRNA or PinX1 siRNA were synchronized by double thymidine block, released, and collected at the indicated six time points. (A and B) Lysates from cells at each time point and asynchronous cells were either immunoblotted to detect endogenous PinX1, phosphorylated histone H3 (P-HH3) as a marker of mitosis, or tubulin as a loading control (A) or stained with propidium iodide and subjected to FACS for cell cycle analysis (black trace, scrambled-siRNA-treated control cells; red trace, PinX1 siRNA-treated cells) (B). Data are representative of five replicate experiments. (C and D) Mean length of time ± SD to enter (C) or to complete (D) mitosis beginning 8 h after release from a double thymidine block for 23 HeLa cells stably expressing GFP-histone H2B and transfected (as verified by BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor Red oligonucleotide fluorescence) with either a scrambled control siRNA (●) or a PinX1 siRNA (■). **, P < 0.01; N.S., not significant. (E) HeLa cells transfected with a scrambled control siRNA or a PinX1 siRNA were synchronized by double thymidine block, released, collected at the time points indicated above the gels, and immunoblotted to detect endogenous PinX1, phosphorylated histone H3 (P-HH3), and cleaved caspase 3. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. A, asynchronous cells.

Live-cell imaging was performed next, to measure the effect of knocking down PinX1 on the time taken to enter mitosis and the length of mitosis. HeLa cells were transiently cotransfected with either PinX1 siRNA or a control scrambled siRNA and BLOCK-iT Alexa Fluor Red fluorescent oligonucleotide to visualize transfected cells. Cells were then synchronized by double thymidine block and released into G1/S phase. Beginning just before entry into mitosis (7 h 30 min after release) BLOCK-iT-positive cells were visualized by live-cell imaging. The control cells took, on average, 10 h 49 min to enter mitosis (Fig. 2C), as defined as the time elapsed between release from the double thymidine block and the aggregation of chromosomes labeled with GFP-histone H2B. These cells then took an average of 66 min to complete mitosis (Fig. 2D), as defined as the time elapsed between the aggregation of chromosomes labeled with GFP-histone H2B and complete separation of two daughter cells. In contrast, PinX1 knockdown cells took an average of 12 h 46 min to enter mitosis, though the average length of mitosis was similar to that of scrambled control cells, namely, 61 min (Fig. 2C and D). Thus, knockdown of PinX1 delays entry into mitosis.

As mitotic delay has been associated with apoptosis (24), we assessed whether PinX1 knockdown promotes apoptosis. Scrambled and PinX1 knockdown cells were released from a double thymidine block, and beginning 8 h later (just prior to mitotic entry), extracts were collected every hour and immunoblotted to detect tubulin (as a loading control), phospho-histone H3 (as a marker of mitosis), PinX1 (to validate knockdown), and cleaved caspase 3 (as a measure of apoptosis). Scrambled control cells entered mitosis, as defined by an increase in phosphorylated histone H3, 10 h after release, and during the course of the experiment exhibited little evidenced of cleaved caspase 3. As already noted, PinX1 knockdown cells had a delayed entry into mitosis, exhibiting elevated phosphorylated histone H3 at 11 h after release but also elevated caspase 3 cleavage beginning at the earliest time point and extending throughout the period of analysis. These effects were not seen in asynchronous cells (Fig. 2E). Thus, knockdown of PinX1 was associated with increased caspase 3 cleavage.

TIN2 inhibits PinX1 binding to TRF1.

PinX1 is recruited to telomeres by binding to TRF1 (33), and as noted above, PinX1 associates with telomeres primarily at mitosis. With regard to a role of TRF1 at mitosis, the enzyme tankyrase-1 poly(ADP-ribosyl)ates and reduces the amount of TRF1 (5, 22), and when tankyrase 1 was knocked down, cells were arrested at mitosis with sister chromatid telomeres still joined (9). The latter phenotype is rescued by knockdown of TIN2, a protein that inhibits the ability of tankyrase 1 to poly(ADP-ribosyl)ate TRF1 (4). Both TIN2 and PinX1 contain the TRF-binding motif F/Y-X-L-X-P (6), and point mutations in the corollary binding site on TRF1 reduce binding to both TIN2 and PinX1 (6). Given these observations, we explored the possibility that PinX1 and TIN2 compete for binding to TRF1.

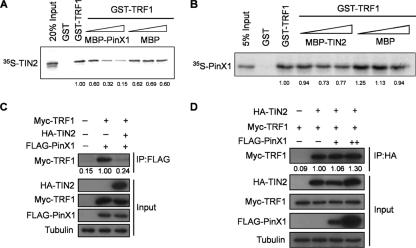

To this end, we first evaluated whether recombinant PinX1 and TIN2 compete for binding to recombinant TRF1. Specifically, bacterially expressed recombinant GST-TRF1 protein tethered to glutathione-Sepharose was incubated with increasing amounts of bacterially expressed recombinant MBP-PinX1 or MBP as a control and in vitro-transcribed and -translated 35S-labeled recombinant Myc-TIN2. Increasing levels of MBP-PinX1 but not MBP reduced the amount of Myc-TIN2 associated with GST-TRF1 (Fig. 3A). Similarly, increasing amounts of recombinant MBP-TIN2 reduced the level of 35S-labeled recombinant PinX1 associated with GST-TRF1 (Fig. 3B). Thus, in agreement with the observation that PinX1 and TIN2 both have similar TRF-binding motifs (6), these two proteins can compete for binding to TRF1 in vitro.

Fig 3.

TIN2 inhibits PinX1 binding to TRF1. (A) Association of rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL)-generated 35S-labeled recombinant TIN2 with bacterially generated recombinant GST-TRF1 upon coincubation with increasing concentrations of recombinant MBP-PinX1. GST and MBP served as controls. The relative amounts of TIN2 normalized to the amount detected with GST-TRF1 are shown below the gel. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. (B) Association of RRL-generated 35S-labeled recombinant PinX1 with bacterially generated recombinant GST-TRF1 upon coincubation with increasing concentrations of recombinant MBP-TIN2. GST and MBP served as controls. The relative amounts of PinX1 normalized to the amount detected with GST-TRF1 are shown below the gel. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. (C) Levels of Myc-TRF1 detected by immunoprecipitation (IP) of FLAG-PinX1 followed by immunoblot assay with an anti-Myc antibody in 293T cells expressing HA-TIN2. Tubulin served as a loading control. The relative amounts of Myc-TRF1 coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-PinX1 normalized to tubulin are shown below the gel. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. (D) Levels of Myc-TRF1 detected by immunoprecipitation of HA-TIN2 followed by immunoblot assay with an anti-Myc antibody in 293T cells expressing FLAG-PinX1. Tubulin served as a loading control. The relative amounts of Myc-TRF1 coimmunoprecipitating with HA-TIN2 normalized to tubulin are shown below the gel. Data are representative of two replicate experiments.

To evaluate the binding properties of these two proteins to TRF1 in cells, FLAG-PinX1 and Myc-TRF1 were ectopically expressed in the absence or presence of HA-TIN2 in HeLa cells, and the amount of FLAG-PinX1 coimmunoprecipitating with Myc-TRF1 was measured. While FLAG-PinX1 was readily coimmunoprecipitated with Myc-TRF1, coexpression of HA-TIN2 reduced this to nearly undetectable levels (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the reverse was not true, namely, the amount of Myc-TRF1 coimmunoprecipitating with HA-TIN2 was not reduced upon ectopic expression of FLAG-PinX1 (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that the occupancy of TIN2 on TRF1 precludes binding of PinX1 but, in the absence of TIN2, PinX1 can bind TRF1. Indeed, while both TIN2 and PinX1 bind TRF1, ectopic PinX1 is mainly found in the nucleoli (29) unless TRF1 is overexpressed (33), whereas ectopic and endogenous TIN2 localize to telomeres in the absence of ectopic TRF1 (13). Taking these findings together, along with the above-described observation that endogenous PinX1 concentrated on telomeres at mitosis, we speculate that TIN2 blocks the binding of PinX1 to TRF1 until mitosis, when TIN2 may dissociate from TRF1 to allow tankyrase 1 to poly(ADP-ribosyl)ate TRF1 and PinX1 to then bind.

PinX1 depletion destabilizes TRF1 in mitosis.

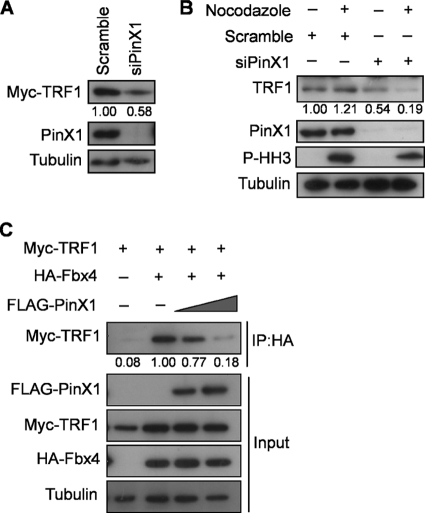

As ectopic PinX1 leads to an accumulation of TRF1 on telomeres (29), we explored whether PinX1 stabilizes TRF1 at mitosis. To this end, we first tested whether reducing PinX1 alters the level of TRF1 protein. Specifically, the level of transiently expressed Myc-TRF1 was measured in HeLa cells transiently transfected with a control scrambled siRNA or PinX1 siRNA. Immunoblot analysis revealed a decrease in Myc-TRF1 protein levels in cells transfected with PinX1 siRNA compared to the levels in control cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 4A). We next compared the levels of TRF1 protein in asynchronous (primarily interphase) versus M-phase-arrested cells in the absence and presence of PinX1 siRNA. PinX1 siRNA halved the level of endogenous TRF1 detected by immunoblotting from lysates of unsynchronized HeLa cells (Fig. 4B, lane 1 versus 3). However, there was a much larger, 6-fold reduction in the amount of TRF1 in the M-phase cells, as assessed by the presence of phosphorylated histone H3, upon knockdown of PinX1 (Fig. 4B, lane 2 versus 4). Thus, PinX1 stabilizes TRF1 protein at mitosis, when PinX1 is found on telomeres.

Fig 4.

Knockdown of PinX1 decreases TRF1 levels at M phase. (A) Myc-TRF1 levels in HeLa cells treated with PinX1 or scramble siRNA, as assessed by immunoblot assay. Tubulin served as a loading control. The relative amounts of Myc-TRF1 normalized to tubulin are shown below the gel. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. (B) HeLa cells treated with a scrambled control siRNA or PinX1 siRNA and either left untreated (interphase cells) or treated with nocodazole and subjected to mitotic shake-off (mitotic cells) were immunoblotted to detect phospho-histone H3 (P-HH3) as a mitotic marker, PinX1, TRF1, or tubulin as a loading control. The relative amounts of TRF1 normalized to tubulin are shown below the gel. Data are representative of two replicate experiments. (C) Amount of Myc-TRF detected by immunoprecipitation (IP) of HA-Fbx4 followed by immunoblot assay with an anti-Myc antibody in 293T cells with increasing amounts of FLAG-PinX1. Tubulin served as a loading control. The relative amounts of Myc-TRF1 coimmunoprecipitated with HA-Fbx4 normalized to tubulin are shown below the gel. Data are representative of three replicate experiments.

Exogenous Fbx4 fosters polyubiquitination of TRF1 (14), whereas knockdown of Fbx4 increases the level of TRF1, an effect that is countered by TIN2 knockdown (31). Hence, we assessed whether the stabilization of TRF1 by PinX1 is due to reduced binding of Fbx4 to TRF1. Specifically, the association of transiently expressed Myc-TRF1 and HA-Fbx4 in human 293T cells was assayed by immunoprecipitation of HA-Fbx4 followed by immunoblotting to detect Myc-TRF1 in the presence of increasing amounts of FLAG-PinX1. As previously observed (34), ectopic HA-Fbx4 alone did not reduce the amount of ectopic Myc-TRF1 protein in cells but did coimmunoprecipitate with Myc-TRF1. However, this association was gradually reduced with increasing levels of FLAG-PinX1, despite the fact that Myc-TRF1 and HA-Fbx4 levels remained relatively constant (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these results suggest that the ability of PinX1 to stabilize TRF1 is consistent with inhibiting the binding of E3 ligases, such as Fbx4, to TRF1.

PinX1 depletion reduces the amount of TRF1 on telomeres at mitosis.

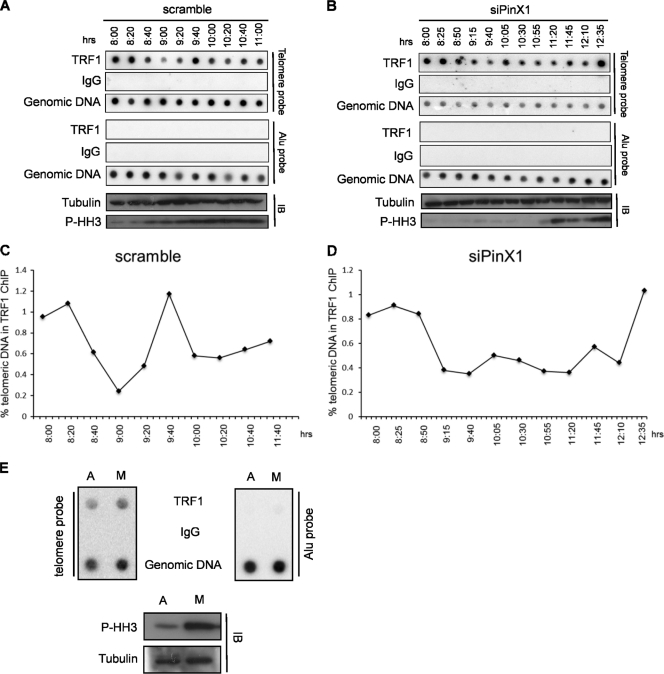

Given that PinX1 both bound to and stabilized TRF1 at mitosis, we explored the impact of reducing PinX1 levels on the amount of TRF1 residing on telomeres throughout mitosis. HeLa cells treated with a scrambled control siRNA or PinX1 siRNA were synchronized by double thymidine block, released, and 8 h later when cells entered G2 phase, cells were collected every 20 or 25 min and subjected to telomeric ChIP assay with an anti-TRF1 antibody and immunoblotting with an anti-phospho-histone H3 antibody to monitor cell cycle progression. In scrambled-siRNA-treated control cells, based on phospho-histone H3 immunoblotting results, the amount of telomeric DNA associated with TRF1 was reduced for a short window of time, principally between 8 h 40 min and 9 h 20 min after release, that corresponded roughly to the G2/M border to early M phase (Fig. 5A and C). Consistent with this timing, the levels of TRF1 associated with telomeric DNA, as assessed by ChIP analysis, were identical in asynchronous and nocodazole-arrested (metaphase) cells (Fig. 5E), supporting the notion that TRF1 is transiently reduced on telomeres between the G2/M border and metaphase. However, the timing of this may vary, as TRF1 has been found, by immunofluorescence analysis, to dissociate from telomeres at metaphase (34). Following this brief dissociation, telomeric TRF1 levels spiked at 9 h 40 min, well into mitosis based on the robust phosphorylation of histone H3, and then decreased to a lower level as the cells completed M phase (Fig. 5A and C). Although in one subsequent experiment the TRF1 ChIP signal was variable throughout the period of analysis, in two other experiments, the TRF1 ChIP signal was similar to the above-described pattern (not shown).

Fig 5.

Knockdown of PinX1 delays the reloading of TRF1 onto telomeres during mitosis. HeLa cells transfected with a scrambled control siRNA (A) or a PinX1 siRNA (B) were synchronized by double thymidine block, released, and collected at the indicated time points after release from the block. Collected cells were split into two portions for ChIP and immunoblot analysis. ChIP analysis was performed with an anti-TRF1 antibody or IgG as a control, followed by Southern hybridization with a telomere or control Alu probe (genomic DNA served as a hybridization control). Immunoblot analysis was performed to detect phosphorylated histone H3 (P-HH3) as a marker of mitosis or tubulin as a loading control. Data are representative of five (A) and three (B) replicate experiments. (C and D) Normalized hybridization intensities of telomeric DNA coimmunoprecipitating with endogenous PinX1 at the indicated time points in scrambled (C) or PinX1 (D) siRNA-treated cells. (E) Asynchronous (interphase) HeLa cells or HeLa cells treated with nocodazole and subjected to mitotic shake-off to enrich metaphase (M) cells were subjected to ChIP analysis and immunoblotted for phosphorylated histone H3 or tubulin as described above. Data are representative of two replicate experiments.

In cells treated with PinX1 siRNA, the reduction of TRF1 associated with telomeres began at essentially the same time (8 h 50 min) as in cells treated with scrambled control siRNA. As already noted above, there was a delay in the accumulation of phosphorylated histone H3, which did not begin until ∼10 h 55 min after release. Most notably, the level of TRF1 associated with telomeres remained constant, and the spike in telomeric TRF1 was not observed until phosphorylated histone H3 levels peaked at the 12 h 35 min time point (Fig. 5B and D). Similar results were observed in two other replicate experiments (not shown). Thus, knockdown of PinX1 reduces the amount of TRF1 on telomeres at mitosis.

DISCUSSION

We report that PinX1 protein accumulated on telomeres at M phase. Knockdown of PinX1 also reduced the amount of total TRF1 protein, as well as accumulation of TRF1 on telomeres, primarily at M phase, in addition to causing delayed entry into M phase and elevated levels of caspase 3 cleavage. Furthermore, TIN2 blocked binding of PinX1 to TRF1, while PinX1 could inhibit binding of the ubiquitin E3 ligase Fbx4 to TRF1. Taking these findings together, we suggest that PinX1 associates with TRF1 at G2/M to early M phase. We speculate that this is a passive event, namely, that PinX1 waits for a TRF1-binding site to become available upon the dissociation of another TRF1-binding protein. The most likely candidate in this regard is TIN2. Admittedly, TIN2 resides on telomeric chromatin both at interphase and mitosis (13), and in agreement, we failed to detect reduced levels of TIN2 on telomere chromatin during M phase (not shown). However, TIN2 is highly abundant at telomeres (23) and associates with many other telomeric proteins (11, 20). As such, TIN2 may still be tethered to telomeres but not bound to TRF1 during this period. Moreover, we demonstrate that TIN2 and PinX1 compete for binding to TRF1, with TIN2 being the dominant binding partner. Indeed, the affinity for TRF1 for peptides containing the F/Y-X-L-X-P TRF1-binding motif of TIN2 is much higher than that of PinX1 (6).

We speculate that the association of PinX1 with TRF1 then retards the degradation of TRF1 at mitosis. Specifically, we demonstrate that knockdown of PinX1 leads to a reduction of endogenous TRF1 protein, primarily at M phase. Mechanistically, PinX1 may inhibit the binding of the E3 ligase Fbx4 to TRF1, as increasing levels of PinX1 reduce the amount of Fbx4 coimmunoprecipitating with TRF1. The consequence of this is an elevation of TRF1 on telomeres during mitosis, as evidenced by the greatly delayed accumulation of telomeric TRF1 during mitosis in cells in which PinX1 levels were reduced.

Finally, we suggest that the stabilization of TRF1 by PinX1 is required for proper M phase. Indeed, knockdown of PinX1 delays the accumulation of cells with 2n DNA content and the accumulation of phosphorylated histone H3, suggesting a defect in the G2/M transition. It is interesting to note that TIN2 inhibits both tankyrase 1 poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of TRF1 (28) and PinX1 binding to TRF1. Furthermore, tankyrase 1 and PinX1 have opposing roles in terms of the stability and residency of TRF1 on telomeres. Overexpression of tankyrase 1 (5) and knockdown of PinX1 both reduce the levels of total and telomeric TRF1. The loss of tankyrase 1 also blocks the separation of sister chromatid telomeres (9). Although highly speculative, it is possible that the accumulation of TRF1 on telomeres fostered by PinX1 during mitosis is related to repackaging telomere chromatin after sister chromatid separation. In this regard, knockdown or knockout of PinX1 leads to lagging chromosomes and anaphase bridges (30, 32), phenotypes that can arise by a failure to separate sister chromatid telomeres (9). In agreement with this hypothesis, anecdotally, we observed more aneuploidy cells among PinX1 siRNA-treated cells than among control-siRNA-treated cells (not shown) during live-cell imaging. Still, the instability induced by the loss of PinX1 is likely to be more complicated than simply regulation of TRF1 stability at mitosis, as the genetic instability observed in PinX1+/− MEFs can be suppressed by reducing telomerase activity (32) and PinX1 has been shown to associate with kinetochores (30), suggesting other functions of PinX1 that could affect mitosis. In summary, we now demonstrate that PinX1 binds telomeres and stabilizes TRF1 at mitosis, perhaps to reload TRF1 onto telomeres and promote M-phase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. Linger for TRF1 cDNA and S. Smith and D. Broccoli for anti-TRF1 antibodies.

This research was supported by NIH grants CA082481 and CA123031 (to C.M.C.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 February 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Armbruster BN, Banik SS, Guo C, Smith AC, Counter CM. 2001. N-terminal domains of the human telomerase catalytic subunit required for enzyme activity in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 7775–7786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banik SS, Counter CM. 2004. Characterization of interactions between PinX1 and human telomerase subunits hTERT and hTR. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 51745–51748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrientos KS, et al. 2008. Distinct functions of POT1 at telomeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 5251–5264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canudas S, et al. 2007. Protein requirements for sister telomere association in human cells. EMBO J. 26: 4867–4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang W, Dynek JN, Smith S. 2003. TRF1 is degraded by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis after release from telomeres. Genes Dev. 17: 1328–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Y, et al. 2008. A shared docking motif in TRF1 and TRF2 used for differential recruitment of telomeric proteins. Science 319: 1092–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chong L, et al. 1995. A human telomeric protein. Science 270: 1663–1667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cook BD, Dynek JN, Chang W, Shostak G, Smith S. 2002. Role for the related poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases tankyrase 1 and 2 at human telomeres. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 332–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dynek JN, Smith S. 2004. Resolution of sister telomere association is required for progression through mitosis. Science 304: 97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grobelny JV, Godwin AK, Broccoli D. 2000. ALT-associated PML bodies are present in viable cells and are enriched in cells in the G(2)/M phase of the cell cycle. J. Cell Sci. 113(Pt 24): 4577–4585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Houghtaling BR, Cuttonaro L, Chang W, Smith S. 2004. A dynamic molecular link between the telomere length regulator TRF1 and the chromosome end protector TRF2. Curr. Biol. 14: 1621–1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karlseder J, et al. 2003. Targeted deletion reveals an essential function for the telomere length regulator Trf1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 6533–6541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim SH, Kaminker P, Campisi J. 1999. TIN2, a new regulator of telomere length in human cells. Nat. Genet. 23: 405–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee TH, Perrem K, Harper JW, Lu KP, Zhou XZ. 2006. The F-box protein FBX4 targets PIN2/TRF1 for ubiquitin-mediated degradation and regulates telomere maintenance. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 759–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martinez P, Blasco MA. 2011. Telomeric and extra-telomeric roles for telomerase and the telomere-binding proteins. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11: 161–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martinez P, et al. 2009. Increased telomere fragility and fusions resulting from TRF1 deficiency lead to degenerative pathologies and increased cancer in mice. Genes Dev. 23: 2060–2075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morgenstern JP, Land H. 1990. A series of mammalian expression vectors and characterisation of their expression of a reporter gene in stably and transiently transfected cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakamura M, Zhou XZ, Kishi S, Lu KP. 2002. Involvement of the telomeric protein Pin2/TRF1 in the regulation of the mitotic spindle. FEBS Lett. 514: 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Okamoto K, Iwano T, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y. 2008. Distinct roles of TRF1 in the regulation of telomere structure and lengthening. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 23981–23988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palm W, de Lange T. 2008. How shelterin protects mammalian telomeres. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42: 301–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sfeir A, et al. 2009. Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell 138: 90–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith S, Giriat I, Schmitt A, de Lange T. 1998. Tankyrase, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres. Science 282: 1484–1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takai KK, Hooper S, Blackwood S, Gandhi R, de Lange T. 2010. In vivo stoichiometry of shelterin components. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 1457–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vakifahmetoglu H, Olsson M, Zhivotovsky B. 2008. Death through a tragedy: mitotic catastrophe. Cell Death Differ. 15: 1153–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Steensel B, de Lange T. 1997. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature 385: 740–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verdun RE, Crabbe L, Haggblom C, Karlseder J. 2005. Functional human telomeres are recognized as DNA damage in G2 of the cell cycle. Mol. Cell 20: 551–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whitfield ML, et al. 2002. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell 13: 1977–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ye JZ, de Lange T. 2004. TIN2 is a tankyrase 1 PARP modulator in the TRF1 telomere length control complex. Nat. Genet. 36: 618–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoo JE, Oh BK, Park YN. 2009. Human PinX1 mediates TRF1 accumulation in nucleolus and enhances TRF1 binding to telomeres. J. Mol. Biol. 388: 928–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yuan K, et al. 2009. PinX1 is a novel microtubule-binding protein essential for accurate chromosome segregation. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 23072–23082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeng Z, et al. 2010. Structural basis of selective ubiquitination of TRF1 by SCFFbx4. Dev. Cell 18: 214–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou XZ, et al. 2011. The telomerase inhibitor PinX1 is a major haploinsufficient tumor suppressor essential for chromosome stability in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121: 1266–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhou XZ, Lu KP. 2001. The Pin2/TRF1-interacting protein PinX1 is a potent telomerase inhibitor. Cell 107: 347–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhu Q, et al. 2009. GNL3L stabilizes the TRF1 complex and promotes mitotic transition. J. Cell Biol. 185: 827–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]