Background: Dysregulated Met signaling can promote tumorigenesis.

Results: Active Met kinase promotes loss of Cbl protein. This is rescued upon inhibition of Met kinase.

Conclusion: Met-dependent Cbl loss in gastric cancers releases other Cbl targets, such as the EGF receptor, from Cbl-mediated attenuation.

Significance: Uncoupling of Met and other RTKs from Cbl negative regulation in gastric cancers provides a mechanism for enhanced RTK signaling in cancer.

Keywords: E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Gastric Cancer, Phosphorylation, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, Ubiquitination, Cbl Signaling

Abstract

Strict regulation of signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) is essential for normal biological processes, and disruption of this regulation can lead to tumor initiation and progression. Signal duration by the Met RTK is mediated in part by the E3 ligase Cbl. Cbl is recruited to Met upon kinase activation and promotes ubiquitination, trafficking, and degradation of the receptor. The Met RTK has been demonstrated to play a role in various types of cancer. Here, we show that Met-dependent loss of Cbl protein in MET-amplified gastric cancer cell lines represents another mechanism contributing to signal dysregulation. Loss of Cbl protein is dependent on Met kinase activity and is partially rescued with a proteasome inhibitor, lactacystin. Moreover, Cbl loss not only uncouples Met from Cbl-mediated negative regulation but also releases other Cbl targets, such as the EGF receptor, from Cbl-mediated signal attenuation. Thus, Met-dependent Cbl loss may also promote cross-talk through indirect enhancement of EGF receptor signaling.

Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs)2 are key components of signaling cascades that promote cellular proliferation and differentiation. These processes are essential for normal human embryogenesis and homeostasis and, when dysregulated, can drive the unconstrained cell growth and invasiveness characteristic of many human cancers.

The Met RTK was initially identified as an oncogenic fusion protein (Tpr-Met) following treatment of the human osteogenic sarcoma (HOS) cell line with the carcinogen N-methyl-N′-nitro-nitrosoguanidine (1, 2). Met was subsequently identified as the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) or scatter factor (3, 4). HGF-Met signaling promotes scatter and an invasive morphogenic response in epithelial cells in cell culture (5) and is required during embryogenesis for development of the placenta, liver, kidney, and neuronal and skeletal muscles (6). In the adult, the HGF-Met signaling axis is involved in wound healing and liver regeneration (7, 8). Tight regulation of Met signaling is required for many of these processes, and dysregulation of the Met signaling axis has been implicated in various human cancers.

Several mechanisms leading to dysregulation of Met in cancer have been identified. These include autocrine/paracrine activation, Met overexpression, genomic amplification, point mutation, and alternative splicing (9). MET amplification occurs frequently in gastric cancers (10) and to a lesser extent in non-small cell lung cancer and glioblastomas (11–14).

The loss of negative regulation represents an additional mechanism through which oncogenic activation of Met can occur (15). Negative regulation of Met is primarily mediated through the Cbl E3 ligase. The Cbl family of E3 ligases consists of three mammalian homologues: c-Cbl, Cbl-b, and Cbl-3 (16–18). These cytoplasmic proteins are conserved in their N-terminal halves and consist of a tyrosine kinase binding (TKB) domain, a linker region, and a RING domain, the latter of which is required for functional E3 ligase activity (reviewed in Ref. 19). The C-terminal portions are less well conserved and include a proline-rich region and a UBA domain (c-Cbl and Cbl-b) (19). The UBA domains of both c-Cbl and Cbl-b facilitate dimerization, but only the Cbl-b UBA domain is able to bind ubiquitin (20–22). The presence of key tyrosine residues as well as proline-rich regions allows Cbl proteins to function also as scaffolds capable of recruiting a number of SH2 and SH3 domain-containing proteins (19).

Both c-Cbl and Cbl-b act as E3 ligases and ubiquitinate their target substrates (reviewed in Ref. 23). The overlap of c-Cbl and Cbl-b function is evident, as CBL−/− or CBLB−/− mice are both viable, but mice deficient in both are embryonic lethal (23, 24). Similarly, in osteoclasts, the depletion of both proteins is required to disrupt the microtubule network and induce apoptosis (25). However, differences in c-Cbl and Cbl-b function exist. c-Cbl and Cbl-b are recruited to EGFR at temporally distinct periods subsequent to EGF stimulation, where c-Cbl is recruited early (5–15 min) and Cbl-b is recruited by 1 h post-stimulation (26). Moreover, whereas c-Cbl or Cbl-b ubiquitination of its substrates, such as RTKs, primarily promotes degradation, Cbl-b-targeted ubiquitination of some substrates, such as the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, impinges on protein-protein interactions but leaves overall protein levels unchanged (reviewed in Ref. 23), highlighting the potentially distinct roles of Cbl proteins.

Upon Met kinase activation, intracellular tyrosine residues are phosphorylated, creating docking sites for a number of downstream signaling molecules. Phosphorylation of Tyr-1003 in the Met juxtamembrane domain allows for direct recruitment of Cbl through the Cbl TKB domain (27). Cbl recruitment to Met is also mediated indirectly through Grb2 (5, 27, 28). Upon Cbl recruitment, Met is ubiquitinated (27). This is required for efficient recognition of Met during trafficking and subsequent degradation in the lysosome (29, 30). The uncoupling of Met from Cbl, through substitution of the Cbl binding site Tyr-1003 with a phenylalanine residue, results in a Met receptor that is poorly ubiquitinated, exhibits enhanced stability and prolonged phosphorylation, and is transforming in vitro and in vivo (29). Moreover, Tpr-Met, a truncated, constitutively active, cytoplasmic variant of Met, lacks the juxtamembrane region containing Tyr-1003, does not recruit the Cbl TKB domain, is not ubiquitinated, and fails to enter the endocytic degradative pathway (31). This escape from entry into the degradative pathway may represent a common mechanism that contributes to the oncogenic activation of many RTKs following chromosomal reorganization (15).

The importance of Cbl-mediated negative regulation of Met as a mechanism counteracting tumorigenesis is further emphasized by the identification of naturally occurring Met variants in cancers that lack the Cbl binding site. Alternatively spliced mutants of Met that result in the excision of exon 14 containing the Cbl TKB domain binding site (Tyr-1003) have been identified in both non-small cell lung cancer cell lines and adenocarcinoma lung tumors (32–34). These Met variants show enhanced stability and prolonged signaling and oncogenic capacity (33). In addition, the gastric cancer cell line Hs746T amplifies MET with a mutation that results in the loss of exon 14 (35). Hence, the loss of negative regulation by Cbl may be selected for even when MET is amplified.

Here, we show that conditions in which MET is amplified in human gastric cancers leads to the loss of Cbl protein. This reflects another mechanism through which Met is able to uncouple from Cbl-dependent negative regulation. Moreover, a loss of Cbl would not only enhance signaling by Met but has the capability of dysregulating the signaling by other Cbl targets such as EGFR. This represents a mechanism of RTK cross-talk in human tumors whereby Cbl loss is dependent on Met kinase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

Antibody 148 was raised in rabbit against a C-terminal peptide of human Met (36). Met DL-21 antibody was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). c-Cbl, Cbl-b, Src, and ubiquitin (P4D1) antibodies were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Met (AF276) and c-Cbl antibodies used for immunofluorescence were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and Epitomics Inc. (Burlingame, CA). Actin and tubulin antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Phospho-specific Met Tyr 1234/1235, EGFR Tyr 992, the general phosphotyrosine pTyr-100, K4B-specific polyubiquitin (D9D5), and total EGFR antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). HA.11 monoclonal and phospho-Src tyrosine 418 antibodies were obtained from Covance (Berkeley, CA) and Invitrogen, respectively. β-Catenin antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences.

HGF was a generous gift from Genentech (San Francisco, CA), and EGF was purchased from Roche Diagnostics. Concanamycin, lactacystin, and PP2 were purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ) and utilized at final concentrations of 0.1, 10, and 10 μm, respectively. The Met inhibitor PHA-665752 was a kind gift from Pfizer (final concentration 0.1 μm).

Cell Culture and Transient Transfections

HEK 293, Okajima, and MKN45 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Snu-5 and KATO II cell lines (a kind gift from Dr. Daniel Haber) were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. Transient transfections with HEK 293 cells were performed using Lipofectamine Plus reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

HEK 293, Okajima, MKN45, Snu-5, and KATO II cells were harvested in TGH lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). HEK 293 transfections were harvested at 48 h post-transfection. Lysates were incubated with antibody for 1 h at 4 °C with gentle rotation followed by a 1-h incubation with protein A- or G-Sepharose beads. Captured proteins were collected by washing three times in TGH lysis buffer, eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked in 3% bovine serum albumin in TBST (10 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm EDTA, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies in TBST overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies in TBST for 1 h. After three washes with TBST, the bound proteins were visualized with an ECL detection kit (Amersham Biosciences).

For Western blot analysis of c-Cbl and Cbl-b ubiquitination, cells were harvested in 150 μl of denaturing TSD lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% SDS, 5 mm DTT, 50 μm MG132, 50 mm N-ethylmaleimide, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). Lysates were boiled at 99 °C for 5 min and then pelleted in a microcentrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. One hundred microliters of supernatant was then diluted to a final concentration of 0.1% SDS with TNESV buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Nonidet P-40, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 10 mm N-ethylmaleimide, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). Immunoprecipitations were performed as described above but with TNESV buffer used in place of TGH lysis buffer.

For blots that required quantitation, membranes were blocked with Li-COR blocking buffer (Li-COR Biosciences) and incubated with primary antibodies as described above followed by incubation with infrared (IR)-conjugated secondary antibodies prior to detection and analysis on the Odyssey IR imaging system (Li-COR Biosciences).

Generation of Cbl-b Constructs

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions to create the Cbl-b constructs with the following primers (and their complementary primers): Cbl-b-(1–483) (5′-CACCAGTCACATCACCAGGATAGTCTCCCCTTGCCCAGAGAAG-3′); -(1–541) (5′-GTGAGAAAACAAGATTAACCACTCCCAGCACCAC-3′); -(1–603) (5′-GTTTGGGACTAATCAGTAAGTGGGATGTCGACTC-3′); -(1–664) (5′-GATGCCCTCCCTCCATCTCTCTGACCTAGGCCACCTCCTGCAAGGCATAGTC-3′); and -(1–821) (5′-CACCTTGGAAGTGAAGAATAAGATCTTCCTCCCCGGCTTTCTCCTCCTCC-3′). Cbl-b 9PA and Cbl-b-(1–664) 9PA constructs were made with the QuikChangeTM multi site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as per the manufacturer's instructions with the following primers: 5′-GACCCACTCCAGATCCCACATCTAAGCCTGGCACCCGTGGCTCCTGCCCTGGATCTAATTCAGAAAGGCATAGTTAG-3′; 5′-GTGAGAAAACAAGATAAACCACTCCCAGCAGCACCTCCTGCCTTAGCAGATCCTCCTCCACCGCCACCTGAAAGACCTCC-3′; and 5′-GCAGCACCTCCTGCCTTAGCAGATCCTCCTGCACCGCCGGCTGAAGCACCTCCACCAATCCCACCAGACAATAGACTG-3′.

siRNA

MKN45 or KATO II cells were plated at a confluency of 3 × 105 cells/well in a 6-well dish and transiently transfected in suspension with 20 nm human MET ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA, 50 nm human CBL siGENOME SMARTpool siRNA, 50 nm human CBLB siGENOME SMARTpool siRNA, or an equal concentration of scrambled control siRNA purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO) with polyethylenimine (PEI) (Sigma-Aldrich). PEI was utilized at a final concentration of 3.75 μg/ml. 48 h after initial transfection, cells were retransfected as described previously. Cells were then lysed 72 h after the initial transfection. Quantitative analysis of knockdown was assessed using the Li-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system as described previously.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. 800 ng of RNA was reverse-transcribed and amplified as described previously (29). The genes 60 S acidic ribosomal protein P0 (RPLP0), TATA-box-binding protein (TBP), splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 4 (SFRS4), and actin (ACTB) were used with geNorm software (37) to generate the normalization factors for c-Cbl and Cbl-b mRNA levels. The primer sequences were as follows: RPLP0 (sense, 5′-CTCAACATCTCCCCCTTCTC-3′; antisense, 5′-GACTCGTTTGTACCCGTTGA-3′); TBP (sense, 5′-TCAGGAAGACGACGTAATGG-3′; antisense, 5′-TTACAGAAGGGCATCACCTG-3′); SFRS4 (sense, 5′-GTTTGGTAGCCGTAGCACAA-3′; antisense, 5′-TGTGGTCATTCCAGCCTTAG-3′); ACTB (sense, 5′-ATCCCCCAAAGTTCACAATG-3′; antisense, 5′-GTGGCTTTTAGGATGGCAAG-3′); CBL (sense, 5′-TCGGCTCCAGAAATTCATTC-3′; antisense, 5′-CCCTGAAGCCATCAATCAGT-3′); and CBLB (sense, 5′-CCAAGAGATGAAGGCTCCAG-3′; antisense, 5′-CTGGTGAGTTCTGCCTGTCA-3′). Real-time PCR was performed using LightCycler 480 and LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Applied Science) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Measurements were taken in duplicate, three times for each set of samples, and three sets of samples (biological replicates) were measured. The level of c-Cbl or Cbl-b mRNA is expressed as the mean -fold difference normalized to the level of c-Cbl or Cbl-b mRNA in the DMSO control.

Confocal Immunofluorescence Microscopy

MKN45 cells were seeded at 1.6 × 105 on glass coverslips (Bellco Glass Inc., Vineland, NJ) in 24-well plates (Nalgene Nunc, Rochester, NY). Forty-eight hours later, cells were washed once with PBS and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) in PBS for 20 min followed by washing three times in PBS. Residual paraformaldehyde was removed with three 5-min washes with 100 mm glycine in PBS. Cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS and blocked for 30 min with blocking buffer (2% bovine serum albumin, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.05% Tween 20, and PBS). Coverslips were incubated with primary and secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h and 40 min, respectively, at room temperature, and nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Coverslips were mounted with Immu-Mount (Thermo Shandon Inc., Pittsburgh, PA). Confocal images were taken using a Zeiss 510 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Canada Ltd., Toronto, Ontario, Canada) with an ×100 objective. Image analysis was carried out using the LSM 5 image browser (Empix Imaging, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Co-localization Studies

Quantification of co-localization between Met and c-Cbl or Met and Cbl-b was performed using MetaMorph software for object-based co-localization measurements. The results were logged into Excel for analysis.

RESULTS

Cbl Protein Levels Are Elevated following Inhibition of Met Kinase

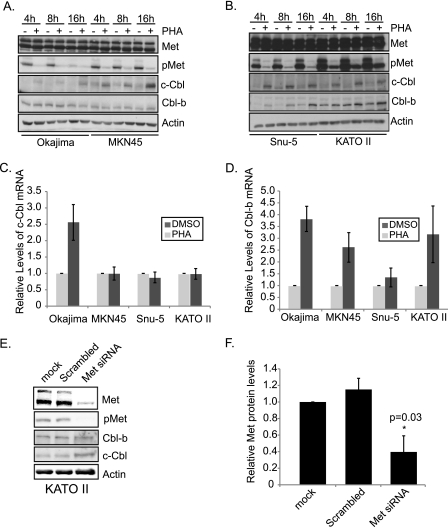

To establish whether amplification of MET in the Okajima, MKN45, Snu-5, and KATO II gastric cancer cell lines leads to constitutive activation of Met protein (10), proteins from whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with Met and phospho-Met antibodies (Fig. 1, A and B). The phospho-Met antibody is specific for tyrosines 1234 and 1235 in the activation loop of the kinase domain. High levels of Met and phospho-Met were observed in all of the cell lines tested.

FIGURE 1.

c-Cbl protein levels are dependent on Met kinase activity. A, Okajima and MKN45 gastric cancer cell lines were treated with the Met inhibitor (0.1 μm PHA-665752) for 4, 8, and 16 h. An equal volume of DMSO was used as a vehicle control. Whole cell lysates were then immunoblotted with antibodies for the specified proteins. B, Snu-5 and KATO II gastric cancer cell lines were treated as described for A. C and D, total RNA from the 16-h time point was isolated from each of the cell lines, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed to ascertain levels of c-Cbl and Cbl-b mRNA. E, Met protein levels were depleted through transient transfection of Met siRNA for 72 h. Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies for the specified proteins. F, the level of Met protein, normalized to actin levels, was quantified from three independent experiments. Plotted here is the mean ± S.E. *, statistical significance of p = 0.03 was determined using Student's t test.

To examine the status of Cbl proteins, lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies raised to the C-terminal regions of c-Cbl and Cbl-b. Whereas the c-Cbl antibody is selective for immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of c-Cbl (supplemental Fig. 1), some weak cross-reactivity of the Cbl-b antibody with c-Cbl was observed when c-Cbl was overexpressed in transient transfections (supplemental Fig. 1). However, in the gastric cancer cell lines used, the Cbl-b antibody detected only Cbl-b, as established by the difference in molecular mass of c-Cbl (110 kDa) when compared with Cbl-b (125 kDa).

Immunoblotting with c-Cbl and Cbl-b antibodies demonstrated low levels of c-Cbl protein in all gastric cancer cell lines tested as well as variable levels of Cbl-b (Fig. 1, A and B). Interestingly, when Met kinase activity was inhibited with a small molecule Met kinase inhibitor (0.1 μm PHA-665752) (38) for 4, 8, or 16 h, a pronounced increase in c-Cbl protein levels was observed in all cell lines, and a moderate increase in Cbl-b levels was observed in two of the four cell lines (Snu-5 and KATO II) (Fig. 1, A and B). PHA-665752 is a small molecule inhibitor that specifically targets Met, and inhibition of unrelated kinases occurs only at an IC50 > 2.5 μm (38). Quantitation of c-Cbl and Cbl-b protein levels from three experimental replicates revealed an inverse correlation between Met kinase activity and c-Cbl or Cbl-b levels in each cell line (supplemental Fig. 2).

To determine whether the change in Cbl protein levels, upon the addition of Met inhibitor, occurs through enhanced transcription, RNA from cells treated or not with Met inhibitor was isolated and reverse-transcribed, and the c-Cbl and Cbl-b levels were determined using quantitative real-time PCR. At 16 h post-treatment with Met inhibitor, a time at which c-Cbl protein levels were maximally elevated, no significant increases in c-Cbl mRNA were observed (Fig. 1, C and D), when compared with the DMSO control. Hence, differences in Cbl protein level upon Met inhibitor treatment were not due to an increase in CBL transcription.

To confirm that the increase in Cbl protein level was Met-dependent, and not due to off-target effects of the inhibitor, knockdown of Met protein was executed with siRNA in KATO II cells (Fig. 1E). Upon depletion of Met protein, c-Cbl levels increased (Fig. 1E), confirming the dependence of Cbl protein loss on Met.

As c-Cbl and Cbl-b can heterodimerize (21, 22), we assessed whether this might play a role in their stability. To address whether Cbl-b influences c-Cbl stability and vice versa, c-Cbl or Cbl-b protein levels were depleted with targeted siRNA. Neither Cbl-b nor c-Cbl knockdown significantly altered steady-state stability levels of the other protein (supplemental Fig. 3).

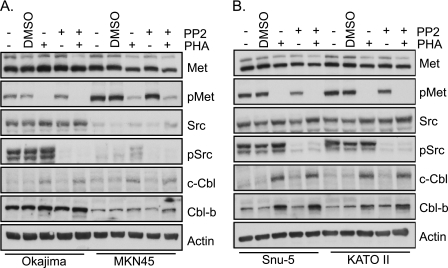

Cbl Levels are Independent of Src Kinase Activity

Overexpression of activated Src kinase has been shown to lead to a decrease in Cbl protein levels (39). Src phosphorylation has also been demonstrated downstream of activated Met kinase (40). To test whether Met-dependent Cbl loss requires Src, cells were treated with the Src inhibitor PP2 (10 μm), a Met inhibitor (0.1 μm PHA-665752), or both. In gastric cancer cells with amplified MET, Src kinase is constitutively active, as evident by the basal tyrosine phosphorylation of Src Tyr-418 (Fig. 2). Interestingly, treatment with the Met inhibitor did not detectably decrease Src tyrosine phosphorylation, and inhibition of Src with PP2, as evident by the loss of Tyr-418 phosphorylation, did not significantly alter Met tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2). Thus, the basal Src activation observed in these gastric cancer cell lines appears independent of Met kinase activity. Importantly, the level of c-Cbl or Cbl-b protein did not increase upon inhibition of Src kinase and was elevated only following inhibition of Met kinase (Fig. 2). Moreover, inhibition of both Met and Src kinases increased the amount of Cbl proteins to a level comparable, but not exceeding, that with Met inhibitor alone. Hence, together these data support the conclusion that in these gastric cancer cell lines, Cbl protein levels are dependent on the kinase activation status of Met and not Src.

FIGURE 2.

Met-dependent Cbl loss is independent of Src kinase activity. Each of the gastric cell lines (A, Okajima and MKN45; B, Snu-5 and KATO II) was treated with nothing, DMSO (vehicle control), 0.1 μm Met inhibitor PHA-665752 (PHA), 10 μm Src inhibitor (PP2), or both PHA-665752 and PP2 for 16 h. Whole cell lysates were then immunoblotted with antibodies for the specified proteins.

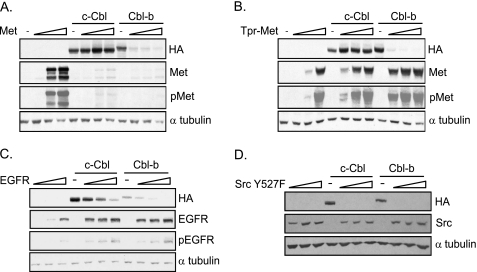

Transient Overexpression of Met Promotes Loss of Cbl-b

To elucidate the requirements through which Met promotes loss of Cbl in gastric cancer cell lines, a transient transfection and structure-function approach was undertaken. Met was initially expressed at increasing concentrations with either HA-tagged c-Cbl or Cbl-b (Fig. 3A). In HEK 293 cells, overexpression of Met protein alone is sufficient to activate Met kinase (Fig. 3A) (36) and constitutive phosphorylation of Met. Increasing levels of Met expression resulted in a significant decrease in Cbl-b protein levels, whereas c-Cbl protein levels were largely unaffected under these conditions (Fig. 3A). Tpr-Met, the truncated, constitutively active, cytoplasmic variant of Met, also induced a dramatic loss in Cbl-b protein upon transient co-expression (Fig. 3B). As expected, the overexpression of either c-Cbl or Cbl-b promoted an efficient loss of total Met protein and a corresponding decrease in phospho-Met (pTyr-1234/1235) levels (Fig. 3A) (27). However, neither c-Cbl nor Cbl-b overexpression promotes loss of Tpr-Met, as Tpr-Met lacks Tyr-1003, the binding site for the Cbl TKB domain (27) (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Loss of Cbl protein upon co-expression with tyrosine kinases. c-Cbl and Cbl-b constructs were expressed in HEK 293 cells alone or with increasing amounts of Met (A), Tpr-Met (B), EGFR (C), or activated Src (Y527F) (D). Lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific to HA (c-Cbl or Cbl-b), Met, pMet, EGFR, pEGFR, Src, or tubulin as indicated.

Quantitation of c-Cbl and Cbl-b mRNA levels in the absence and presence of Met show that Cbl-b mRNA levels are not decreased upon transient co-expression with Met (supplemental Fig. 4A). Thus, this finding supports our data in gastric cancer cell lines, demonstrating that a decrease in Cbl protein levels in the presence of active Met protein is not due to alterations in the level mRNA. Co-expression of either c-Cbl or Cbl-b with increasing levels of EGFR or activated Src (Src Y527F) resulted in a decrease in both c-Cbl and Cbl-b protein levels (Fig. 4, C and D), corroborating previously published data (39, 41). Because transient Met expression promoted a significant and consistent loss of Cbl-b protein levels, structure-function studies were carried out with Cbl-b.

FIGURE 4.

Met-dependent Cbl-b loss requires Met kinase activity and Cbl-b TKB and RING function. A, wild-type and kinase-dead Met (K1110A) were transiently transfected alone or with wild-type Cbl-b in HEK 293 cells. Cells were lysed 48 h after transfection and lysates probed for the specified proteins. B, a schematic of the structure of the different HA-tagged Cbl-b constructs used. HA-tagged c-Cbl is also presented for comparison. Both proteins are highly homologous in their TKB (for Cbl specificity), linker (L), and RING domains. The TKB domain is composed of three subdomains: a 4-helix bundle, a calcium-binding EF hand, and a variant SH2 domain, all of which contribute to phosphotyrosine binding. The linker region contains tyrosines that may be phosphorylated to enhance E3 ligase activity of the RING domain. The C-terminal portion is more variable between c-Cbl and Cbl-b and allows both proteins to act as scaffold proteins, as it includes tyrosine residues (Tyr-700, Tyr-731, and Tyr-770 for c-Cbl; Tyr-665 and Tyr-709 for Cbl-b) and proline-rich regions that recruit SH2 and SH3 domain-containing proteins. The UBA domain is able to facilitate homo- and heterodimerization of c-Cbl and Cbl-b but is also functionally distinct between the two proteins. The Cbl-b UBA domain is able to bind ubiquitin moieties, whereas the c-Cbl UBA domain is not. C, this panel of Cbl-b constructs was expressed alone or with Met. Whole cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific to HA (Cbl-b), Met, or actin as designated. The molecular weight ladder is indicated to the left of the HA panel. D, a schematic depicting the domains and mutations (where applicable) of the different HA-tagged Cbl-b constructs. The Cbl-b 9PA construct has nine prolines, in putative Grb2 binding sites, mutated to alanines. E, wild-type, truncated, or mutated Cbl-b constructs were expressed alone or with Met. Membranes were probed with the specified antibodies, and molecular weight markers are shown to the left of the HA panel. F, lysates from HEK 293 cells where various Cbl-b constructs or Met were overexpressed were incubated with GST or GST-Grb2 proteins conjugated to glutathione-Sepharose beads. Met was used as a positive control, and all of the Cbl constructs shown, with the exception of Cbl-b-(1–664) 9PA, are associated with the GST-Grb2 protein. WCL, whole cell lysate.

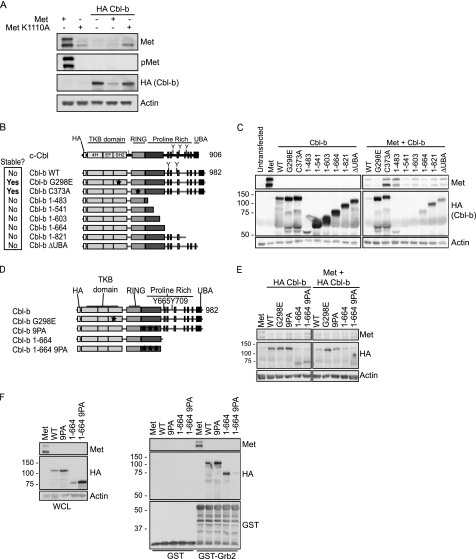

Met-dependent Cbl-b Loss Requires Met Kinase Activity and Intact Cbl-b TKB and RING Domains

As a means to validate the requirement for Met kinase activity in promoting Cbl loss, wild-type Met and a mutant unable to promote transfer of the γ-ATP (kinase-dead K1110A) constructs were expressed alone or with HA-tagged Cbl-b. Co-expression of wild-type Met and Cbl-b resulted in a loss of both Met and Cbl-b protein (Fig. 4A). However, this loss was not observed upon co-expression of Met K1110A with Cbl-b (Fig. 4A), demonstrating the dependence of Cbl protein loss on Met kinase activity.

To determine the regions or domains of Cbl-b required for Cbl-b loss, a panel of HA-tagged Cbl-b mutants (Fig. 4B) consisting of wild-type Cbl-b, a Cbl-b unable to bind Met through its TKB domain (G298E), an E3 ligase-dead mutant (Cbl-b C373A), and multiple truncation mutants that excise the UBA domain (Cbl-b ΔUBA), proline-rich regions, and/or key tyrosine residues (Tyr-665/Tyr-709) (Cbl-b-(1–483), -(1–541), -(1–603), -(1–664), and -(1–821)) were examined for their stability when expressed in HEK 293 cells alone or with wild-type Met. With the exception of the G298E and C373A mutants, in the presence of Met, the protein levels of each Cbl-b construct were decreased as compared with their expression levels in the absence of Met (Fig. 4C). Cbl-b G298E, which abrogates TKB function, uncoupling Met-Cbl-b direct interaction, and Cbl-b C373A, which lacks functional E3 ligase activity in the RING domain, did not exhibit protein loss upon co-expression with Met, indicating a necessity for TKB and RING function in promoting Cbl-b loss downstream from Met (Fig. 4C). In support of this observation, when c-Cbl or Cbl-b were transiently expressed in HEK 293 cells with Met and FLAG-tagged ubiquitin, increased ubiquitination of Cbl-b, as compared with c-Cbl, was observed, an effect that was enhanced upon treatment with the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin prior to cell lysis (supplemental Fig. 5). The low level of c-Cbl ubiquitination following transient transfection substantiates the lack of c-Cbl protein loss, when compared with Cbl-b, upon overexpression with Met.

Cbl-b is in part recruited to Met indirectly through the Grb2 adaptor protein (27). The requirement for indirect association of Met and Cbl-b (via Grb2) for Met-dependent Cbl-b loss was also assessed. The C-terminal half of Cbl-b contains six putative Grb2 binding sites. Three of these sites were absent in Cbl-b-(1–664), and the remaining three sites were mutated through site-directed mutagenesis (Cbl-b-(1–664) 9PA). This construct, as demonstrated through GST-Grb2 pulldown (Fig. 4F), is dramatically impaired in its ability to bind Grb2 as compared with wild-type Cbl-b. The protein levels of Cbl-b-(1–664) 9PA decrease in the presence of Met (Fig. 4E), demonstrating that recruitment of Grb2 is dispensable for Cbl-b protein loss. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of these three Grb2 binding sites on Cbl-b. Altogether, this demonstrates that the C-terminal UBA domain on Cbl-b, as well as the proline-rich regions and tyrosines 665 and 709, is dispensable for Met-dependent Cbl-b protein loss after transient transfection. Furthermore, as Cbl-b ubiquitination was observed and Cbl-b E3 ligase activity is required, these data support the conclusion that that Cbl-b loss may occur through self-ubiquitination.

Met-dependent Cbl Loss Requires Proteasome Activity

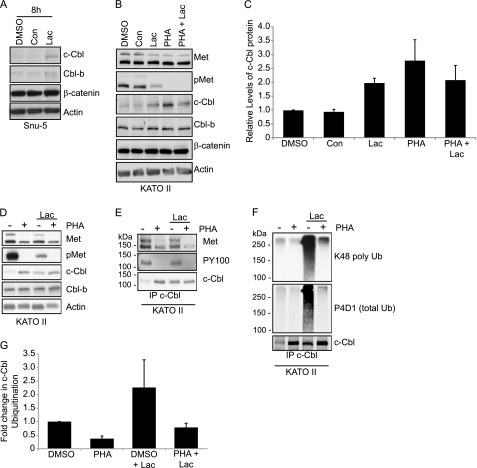

Basal activation of Met kinase in the gastric cancer cell lines correlates with low levels of Cbl proteins. This suggests that Met signaling may target Cbl protein for degradation. To test whether Cbl loss was induced in response to Met activity, HEK 293 cells, which stably express a doxycycline-inducible Met, were transiently transfected with HA-Cbl-b and stimulated with HGF (supplemental Fig. 6A). By 2 h of HGF stimulation, Cbl-b levels decreased when compared with the unstimulated control (supplemental Fig. 6A). To determine whether Cbl-b protein was being degraded through the lysosome or the proteasome, inhibitors (concanamycin or lactacystin, respectively) for both were used. Cells were pretreated with concanamycin or lactacystin for 4 h prior to HGF stimulation. The addition of concanamycin did not affect Cbl-b loss with HGF stimulation, whereas the presence of lactacystin partially rescued Cbl-b levels (supplemental Fig. 6A). In Snu-5 and KATO II cells, lactacystin treatment resulted in an increase in c-Cbl levels, as shown in Fig. 5, A and B. Quantitation of three independent experiments demonstrates that upon Met inhibition, c-Cbl protein levels increased 2.5-fold (Fig. 5C). The same trend was observed in Okajima and MKN45 cells (supplemental Fig. 6B). Altogether, these data implicate a role for the proteasome in c-Cbl degradation downstream from kinase-active Met.

FIGURE 5.

c-Cbl protein is polyubiquitinated and its loss is dependent on proteasome activity. A, Snu-5 cells were treated with inhibitors for the lysosome (0.1 μm concanamycin (Con)) or proteasome (10 μm lactacystin (Lac)) for 8 h. Lysates were immunoblotted as specified. B, KATO II cells were treated with lysosome (0.1 μm concanamycin), proteasome (10 μm lactacystin), or Met inhibitor (0.1 μm PHA-665752 (PHA)) or both the proteasome and Met inhibitors for 8 h. Lysates were probed with the designated antibodies. C, quantitation of Cbl protein levels (mean ± S.E.) under the different conditions plotted here. D, whole cell lysates of KATO II cells treated with DMSO or 0.1 μm PHA-665752 overnight (16 h) followed by the addition of DMSO or 10 μm lactacystin (8 h) prior to cell lysis. Membranes were probed with the designated antibodies. E, lysates from D were immunoprecipitated (IP) with c-Cbl antibody and blotted as specified. The molecular weight marker is shown at the left of each panel. F, KATO II lysates were immunoprecipitated with c-Cbl antibody and probed with the specified total (P4D1) and polyubiquitin (K48 poly Ub) antibodies. G, ubiquitination of c-Cbl (normalized to amounts of c-Cbl immunoprecipitated) was quantified from five independent experiments, and the mean ± S.E. is plotted here.

Considering that c-Cbl protein levels are increased upon inhibition of the proteasome, we assessed whether c-Cbl is ubiquitinated under basal conditions in gastric cancer cells. To this end, KATO II cells were treated overnight (for 16 h) with Met inhibitor followed by treatment with lactacystin for 8 h. Subsequent to cell lysis, c-Cbl proteins were immunoprecipitated under denaturing conditions to uncouple the associated proteins, and ubiquitination was detected using anti-ubiquitin antibodies (P4D1 and antibodies raised to Lys-48-linked polyubiquitin (D9D5)). c-Cbl is ubiquitinated in the presence of active Met, which is diminished following the inhibition of Met, even though c-Cbl protein levels are elevated (Fig. 5, F and G). The comparable patterns of total ubiquitin and Lys-48-linked polyubiquitin indicate that c-Cbl is polyubiquitinated and contains Lys-48-linked chains (Fig. 5F). As Lys-48-linked chains are thought to promote proteasomal degradation, and c-Cbl ubiquitination is most apparent where Met is active and following treatment with lactacystin (Fig. 5F), we concluded that Met activation promotes c-Cbl polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome.

In gastric cancer cells, c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitates with Met and is tyrosine-phosphorylated, both of which events are decreased in the presence of Met inhibitor and are hence dependent on Met kinase activity (Fig. 5E). In comparison, although Cbl-b can co-immunoprecipitate with Met in gastric cancer cell lines, Cbl-b tyrosine phosphorylation was not observed (supplemental Fig. 6C). In support of the enhanced association of c-Cbl with Met, c-Cbl co-localizes with Met both at the membrane and in punctate structures in MKN45 gastric cancer cells (supplemental Fig. 7B). Moreover, we observed 64% co-localization of c-Cbl protein with Met by immunofluorescence as compared with only 34% of the Cbl-b protein (supplemental Fig. 7A). Hence, the enhanced association of Met and c-Cbl compared with Cbl-b in gastric cancer cells, as observed by immunofluorescence, likely contributes to the enhanced ubiquitination and decreased stability of c-Cbl over Cbl-b protein levels.

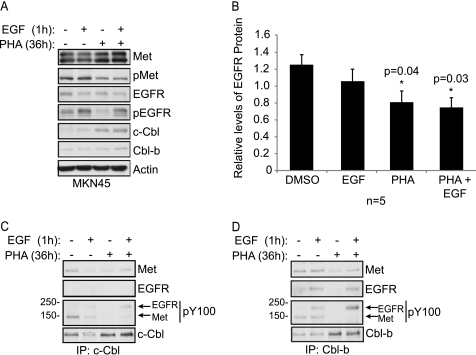

EGFR Degradation and Cbl Recruitment Are Impaired in MET-amplified Gastric Cancer Cell Lines

Cbl proteins negatively regulate multiple receptor tyrosine kinases including EGFR (reviewed in Ref. 42). Hence, to investigate whether Met-dependent Cbl loss in gastric cancer cell lines augments the stability and/or signaling of other kinases, the stability of EGFR was assessed in MKN45 cells upon EGF stimulation in the presence or absence of Met inhibitor (Fig. 6A). Although stimulation with EGF promotes EGFR protein loss, EGFR loss is statistically significant only in the presence of the Met inhibitor, when Cbl levels are elevated, and not in control cells (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Met-dependent Cbl loss releases EGFR from Cbl-targeted degradation. A, MKN45 cells were treated with Met inhibitor (36 h) and then stimulated or not with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 1 h. Proteins were immunoblotted with specific antibodies. B, EGFR protein levels ± Met inhibitor, EGF, or both EGF and inhibitor were quantified from five representative experiments. EGFR levels were normalized to actin levels, and the means ± S.E. were plotted. *, statistical significance of p < 0.04 was determined using Student's t test. C and D, lysates from A were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific to c-Cbl (C) or Cbl-b (D) and the co-immunoprecipitated proteins separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with the designated antibodies. Sizes of the molecular weight markers are depicted on the left, and the arrows designate the migration of phospho-proteins corresponding to Met and EGFR.

To establish whether the enhanced degradation of EGFR in MKN45 cells in the presence of EGF and the Met inhibitor corresponds with increased association between Cbl and EGFR, the ability of Cbl and EGFR to co-immunoprecipitate was investigated. Under basal conditions in which Met is active, c-Cbl co-immunoprecipitates with a phospho-protein corresponding to the molecular weight of Met, which disappears upon treatment with the Met inhibitor (Fig. 6C). Cbl-b also co-immunoprecipitates with active Met (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, upon stimulation with EGF, phospho-EGFR predominantly co-immunoprecipitates with Cbl-b (Fig. 6, C and D). Notably, this EGF-dependent association of Cbl-b and EGFR is significantly enhanced when Met kinase activity is inhibited (Fig. 6D). c-Cbl also co-immunoprecipitates with EGFR following stimulation with EGF, and although this is enhanced following inhibition of Met, this co-immunoprecipitation is consistently less that with Cbl-b (Fig. 6C). Hence, under conditions where Met is inhibited and Cbl protein levels are increased, Cbl is able to more efficiently target EGFR for degradation due to enhanced association with EGFR and decreased competition for Cbl binding from Met.

DISCUSSION

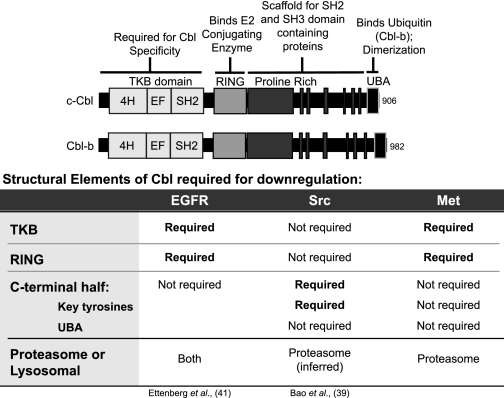

Protein tyrosine kinases act as molecular switches to control a variety of cellular signals, and their dysregulation contributes to many human malignancies. Notably, members of the Cbl family can serve as negative regulators for many tyrosine kinases, and loss of Cbl-dependent negative regulation is recognized as a mechanism that contributes to tumorigenesis (43). Here we have demonstrated Met-dependent loss of Cbl protein as a mechanism to decrease Cbl-mediated negative regulation of RTKs in human cancer. Although other reports have detailed the loss of Cbl protein downstream from EGFR and Src kinases (39, 41, 44), this is the first report to demonstrate that Cbl protein loss is dependent on an activated Met kinase in human tumors.

The mechanism of Cbl loss downstream from Met is dependent on an intact Cbl TKB domain and RING domain. This is distinct from Src-dependent Cbl loss, which occurs independently of the Cbl RING domain (Table 1) (39). Furthermore, Src-dependent Cbl loss requires tyrosines Tyr-700, Tyr-731, and Tyr-774 in the C-terminal half of Cbl (39, 45), of which the equivalent tyrosines (Tyr-665 and Tyr-709) are dispensable for Met-dependent Cbl-b loss (Fig. 4). In support of this, we have demonstrated that Met-dependent c-Cbl or Cbl-b loss in multiple gastric tumor cell lines is independent of Src kinase activity. In a manner similar to Met, Cbl-b loss downstream from the EGFR also requires both intact Cbl TKB and RING domains and not C-terminal proline-rich or UBA regions (41).

TABLE 1.

Structural requirements for Cbl loss downstream from various tyrosine kinases

Inhibition of the proteasome rescues Cbl levels downstream from Met kinase. This supports the requirement for an intact Cbl E3 ligase function whereby Cbl is auto-ubiquitinated following Met activation. Consistent with this understanding, c-Cbl ubiquitination is elevated in gastric cancer cell lines where Met is activated. Similarly ubiquitination of Cbl has been observed downstream from several activated kinases including EGFR, Src, and CSF-1 receptor (39, 41, 46). Met kinase activity is required for Cbl loss (Figs. 1 and 4A). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Cbl is required for activation of its E3 ligase (47, 48), and mutants that either remove the tyrosine phosphorylation site in the linker region of Cbl or promote loss of ligase activity are increasingly found in tumors (49–53). Hence, the ubiquitination of Cbl, subsequent to constitutive Met kinase activation, may be a negative feedback mechanism regulating c-Cbl stability in human tumors. Other E3 proteins have been shown to self-ubiquitinate and target themselves for degradation, and regulation of Cbl activity, by mediating its stability, has been documented previously to occur (reviewed in Ref. 44).

We show a preferential loss of c-Cbl protein over Cbl-b downstream from Met in multiple gastric cancer cells lines. This difference in specificity is reflected by enhanced association of Met with c-Cbl in gastric cancer cell lines over Cbl-b and elevated ubiquitination of c-Cbl under these conditions. Alternatively, following transient co-transfections, we observed a preferential Met-dependent decrease in Cbl-b over c-Cbl protein levels, which correlated with enhanced ubiquitination of Cbl-b under these conditions. Hence, Met-dependent Cbl loss correlates with preferential association of Met with c-Cbl versus Cbl-b under different conditions. Although the basis for this is unclear, Cbl-b is preferentially targeted for ubiquitination and degradation in T cells in response to CD28 stimulation of TCR (reviewed in Ref. 23), whereas upon treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia patients with the Bcr/Abl inhibitor imatinib, c-Cbl expression and protein levels increase, and Cbl-b levels decrease (23, 54). Moreover, c-Cbl and Cbl-b show distinct temporal association with the EGFR following stimulation with EGF (26), supporting the idea that c-Cbl versus Cbl-b may be enriched in distinct subcellular compartments.

Constitutive Met activation following amplification in gastric cancers is not the result of an autocrine loop, as HGF mRNA is undetectable in these cell lines (10). Moreover, sequencing of Met has not yet revealed the presence of known activating mutations in MKN45, Snu-5, and KATO II gastric cancer cell lines where MET is amplified (10). Thus, the loss of Cbl protein and negative regulation of Met may be a contributing factor enhancing Met prolonged activation in the absence of ligand. Tpr-Met, an oncogenic Met variant, is the result of a genomic rearrangement, where a leucine zipper dimerization domain promotes enforced dimerization of the Met kinase in the absence of ligand, driving constitutive activation and phosphorylation (2, 55). However, another mechanism contributing to the transforming ability of Tpr-Met is the uncoupling from Cbl-mediated negative regulation (31). Tpr-Met is cytoplasmically located, lacks the juxtamembrane Tyr-1003, and is thus unable to associate with Cbl, enter the endocytic pathway, and be degraded efficiently (31). Restoration of the Cbl binding site, membrane localization, and Cbl expression are required for the down-regulation of Tpr-Met and suppression of transformation (31). In murine models, wild-type or mutated Met (M1250T) under the murine mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter are weakly transforming (56). However, mice expressing a Met receptor with both M1250T and Y1003F mutations, thereby diminishing the ability of Cbl to bind and ubiquitinate Met, exhibit a greater penetrance and a shorter latency (∼100 days less) (56), demonstrating that the loss of Cbl-mediated negative regulation enhances Met oncogenic capabilities. Interestingly, the human gastric cancer cell line Hs746T expresses a mutated Met receptor (Met Δexon14) that lacks the direct Cbl binding site (Tyr-1003) in addition to amplification of MET (35). In these cells, inhibition of constitutively active Met does not impact c-Cbl or Cbl-b protein levels (data not shown), supporting the idea that Met-dependent Cbl loss requires association between the two proteins and highlighting that selection can occur for alternative mechanisms that uncouple Met from Cbl. Moreover, in lung cancers where tested, more than 80% of the tumors with c-CBL genomic changes also exhibit mutations in either MET or EGFR (52). Exogenous expression of c-Cbl in lung cancer cells can also inhibit tumor growth and metastasis in a xenograft mouse model (57). Thus, taken together, these findings support the idea that the Met-dependent loss of Cbl proteins exhibited in the four gastric cancer cell lines examined here (Okajima, MKN45, Snu-5, and KATO II) would lead to enhanced dysregulation of MET and, potentially, other Cbl targets.

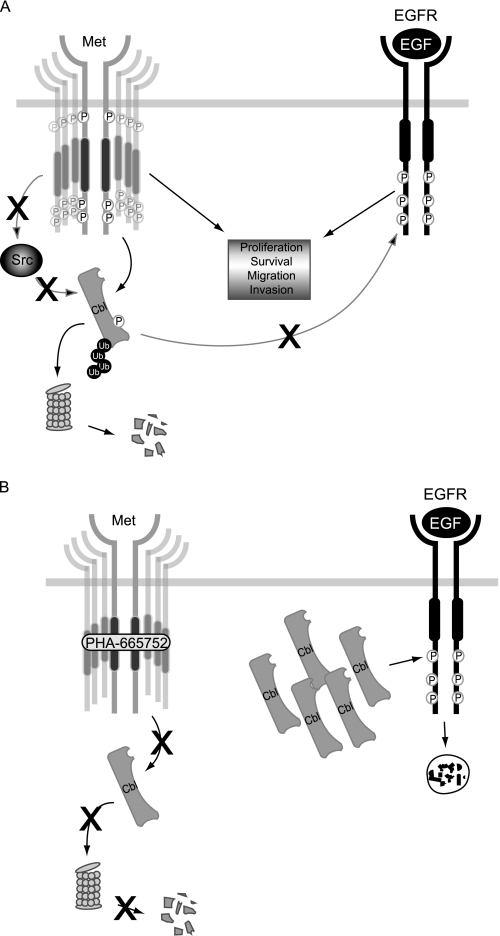

Notably, in the four gastric cancer cell lines tested, Met-dependent suppression of Cbl levels augments the stability of other Cbl target proteins such as EGFR (Fig. 6). This has important implications for RTK cross-talk, whereby activation of Met can lead to tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of EGFR and vice versa (43). Hence, Met-dependent Cbl loss in gastric cancers thereby provides a mechanism through which Met activation can indirectly enhance EGFR signaling (Fig. 7). Met may also promote EGFR stability by virtue of its overexpression, thereby sequestering Cbl away from EGFR. Thus, in these cancer cells, Met recruitment of Cbl and targeted down-regulation may take advantage of a normal feedback mechanism to regulate Cbl, creating a platform of activated RTKs that together contribute to the potentiation of oncogenic signaling.

FIGURE 7.

Model of Met-dependent Cbl loss in gastric cancer cells with amplified MET. A, under basal conditions, signaling by active Met promotes cell proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion. Constitutively active Met also promotes phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and eventual proteasomal degradation of Cbl protein in a Src-independent manner. This uncouples EGFR from Cbl-mediated negative regulation, allowing it to also promote downstream signaling. B, in the presence of the Met inhibitor, where Cbl is no longer phosphorylated and ubiquitinated, Cbl protein accumulates allowing for more efficient targeting of EGFR for lysosomal degradation in the presence of EGF stimulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Park laboratory for helpful comments on the manuscript. We also thank Genentech Inc. for providing HGF, Pfizer for PHA-665752, and Dr. D. Haber for the Snu-5 and KATO II cell lines.

This work was supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship (CGS) doctoral research award (to A. L.), a Cancer Consortium grant (to M. D.), and an operating grant (to M. P.), all from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–7.

- RTK

- receptor tyrosine kinase

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- TKB

- tyrosine kinase binding

- SH2 and -3

- Src homology 2 and 3

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- UBA

- ubiquitin-associated.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cooper C. S., Park M., Blair D. G., Tainsky M. A., Huebner K., Croce C. M., Vande Woude G. F. (1984) Molecular cloning of a new transforming gene from a chemically transformed human cell line. Nature 311, 29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park M., Dean M., Cooper C. S., Schmidt M., O'Brien S. J., Blair D. G., Vande Woude G. F. (1986) Mechanism of Met oncogene activation. Cell 45, 895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bottaro D. P., Rubin J. S., Faletto D. L., Chan A. M., Kmiecik T. E., Vande Woude G. F., Aaronson S. A. (1991) Identification of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor as the c-met proto-oncogene product. Science 251, 802–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Naldini L., Weidner K. M., Vigna E., Gaudino G., Bardelli A., Ponzetto C., Narsimhan R. P., Hartmann G., Zarnegar R., Michalopoulos G. K., et al. (1991) Scatter factor and hepatocyte growth factor are indistinguishable ligands for the MET receptor. EMBO J. 10, 2867–2878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fournier T. M., Kamikura D., Teng K., Park M. (1996) Branching tubulogenesis but not scatter of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells requires a functional Grb2 binding site in the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22211–22217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vasyutina E., Stebler J., Brand-Saberi B., Schulz S., Raz E., Birchmeier C. (2005) CXCR4 and Gab1 cooperate to control the development of migrating muscle progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 19, 2187–2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huh C. G., Factor V. M., Sánchez A., Uchida K., Conner E. A., Thorgeirsson S. S. (2004) Hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met signaling pathway is required for efficient liver regeneration and repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4477–4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borowiak M., Garratt A. N., Wüstefeld T., Strehle M., Trautwein C., Birchmeier C. (2004) Met provides essential signals for liver regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 10608–10613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peschard P., Park M. (2007) From Tpr-Met to Met, tumorigenesis and tubes. Oncogene 26, 1276–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smolen G. A., Sordella R., Muir B., Mohapatra G., Barmettler A., Archibald H., Kim W. J., Okimoto R. A., Bell D. W., Sgroi D. C., Christensen J. G., Settleman J., Haber D. A. (2006) Amplification of MET may identify a subset of cancers with extreme sensitivity to the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor PHA-665752. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2316–2321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Engelman J. A., Zejnullahu K., Mitsudomi T., Song Y., Hyland C., Park J. O., Lindeman N., Gale C. M., Zhao X., Christensen J., Kosaka T., Holmes A. J., Rogers A. M., Cappuzzo F., Mok T., Lee C., Johnson B. E., Cantley L. C., Jänne P. A. (2007) MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science 316, 1039–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Okuda K., Sasaki H., Yukiue H., Yano M., Fujii Y. (2008) Met gene copy number predicts the prognosis for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 99, 2280–2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cappuzzo F., Jänne P. A., Skokan M., Finocchiaro G., Rossi E., Ligorio C., Zucali P. A., Terracciano L., Toschi L., Roncalli M., Destro A., Incarbone M., Alloisio M., Santoro A., Varella-Garcia M. (2009) MET increased gene copy number and primary resistance to gefitinib therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 20, 298–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(2008) Nature 455, 1061–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peschard P., Park M. (2003) Escape from Cbl-mediated down-regulation: a recurrent theme for oncogenic deregulation of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cancer Cell 3, 519–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Langdon W. Y., Hartley J. W., Klinken S. P., Ruscetti S. K., Morse H. C., 3rd (1989) v-cbl, an oncogene from a dual recombinant murine retrovirus that induces early B-lineage lymphomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 1168–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Keane M. M., Rivero-Lezcano O. M., Mitchell J. A., Robbins K. C., Lipkowitz S. (1995) Cloning and characterization of cbl-b: a SH3-binding protein with homology to the c-cbl proto-oncogene. Oncogene 10, 2367–2377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Keane M. M., Ettenberg S. A., Nau M. M., Banerjee P., Cuello M., Penninger J., Lipkowitz S. (1999) Cbl-3: a new mammalian Cbl family protein. Oncogene 18, 3365–3375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thien C. B., Langdon W. Y. (2001) Cbl: many adaptations to regulate protein tyrosine kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 294–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bartkiewicz M., Houghton A., Baron R. (1999) Leucine zipper-mediated homodimerization of the adaptor protein c-Cbl. A role in c-Cbl's tyrosine phosphorylation and its association with epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30887–30895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kozlov G., Peschard P., Zimmerman B., Lin T., Moldoveanu T., Mansur-Azzam N., Gehring K., Park M. (2007) Structural basis for UBA-mediated dimerization of c-Cbl ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27547–27555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peschard P., Kozlov G., Lin T., Mirza I. A., Berghuis A. M., Lipkowitz S., Park M., Gehring K. (2007) Structural basis for ubiquitin-mediated dimerization and activation of the ubiquitin protein ligase Cbl-b. Mol. Cell 27, 474–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thien C. B., Langdon W. Y. (2005) c-Cbl and Cbl-b ubiquitin ligases: substrate diversity and the negative regulation of signalling responses. Biochem. J. 391, 153–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naramura M., Jang I. K., Kole H., Huang F., Haines D., Gu H. (2002) c-Cbl and Cbl-b regulate T cell responsiveness by promoting ligand-induced TCR down-modulation. Nat. Immunol. 3, 1192–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purev E., Neff L., Horne W. C., Baron R. (2009) c-Cbl and Cbl-b act redundantly to protect osteoclasts from apoptosis and to displace HDAC6 from beta-tubulin, stabilizing microtubules, and podosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 4021–4030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pennock S., Wang Z. (2008) A tale of two Cbls: interplay of c-Cbl and Cbl-b in epidermal growth factor receptor down-regulation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 3020–3037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peschard P., Fournier T. M., Lamorte L., Naujokas M. A., Band H., Langdon W. Y., Park M. (2001) Mutation of the c-Cbl TKB domain binding site on the Met receptor tyrosine kinase converts it into a transforming protein. Mol. Cell 8, 995–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsygankov A. Y., Teckchandani A. M., Feshchenko E. A., Swaminathan G. (2001) Beyond the RING: CBL proteins as multivalent adapters. Oncogene 20, 6382–6402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abella J. V., Peschard P., Naujokas M. A., Lin T., Saucier C., Urbé S., Park M. (2005) Met/Hepatocyte growth factor receptor ubiquitination suppresses transformation and is required for Hrs phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9632–9645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammond D. E., Urbé S., Vande Woude G. F., Clague M. J. (2001) Down-regulation of MET, the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor. Oncogene 20, 2761–2770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mak H. H., Peschard P., Lin T., Naujokas M. A., Zuo D., Park M. (2007) Oncogenic activation of the Met receptor tyrosine kinase fusion protein, Tpr-Met, involves exclusion from the endocytic degradative pathway. Oncogene 26, 7213–7221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Onozato R., Kosaka T., Kuwano H., Sekido Y., Yatabe Y., Mitsudomi T. (2009) Activation of MET by gene amplification or by splice mutations deleting the juxtamembrane domain in primary resected lung cancers. J. Thorac. Oncol. 4, 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kong-Beltran M., Seshagiri S., Zha J., Zhu W., Bhawe K., Mendoza N., Holcomb T., Pujara K., Stinson J., Fu L., Severin C., Rangell L., Schwall R., Amler L., Wickramasinghe D., Yauch R. (2006) Somatic mutations lead to an oncogenic deletion of Met in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ma P. C., Jagadeeswaran R., Jagadeesh S., Tretiakova M. S., Nallasura V., Fox E. A., Hansen M., Schaefer E., Naoki K., Lader A., Richards W., Sugarbaker D., Husain A. N., Christensen J. G., Salgia R. (2005) Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 65, 1479–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Asaoka Y., Tada M., Ikenoue T., Seto M., Imai M., Miyabayashi K., Yamamoto K., Yamamoto S., Kudo Y., Mohri D., Isomura Y., Ijichi H., Tateishi K., Kanai F., Ogawa S., Omata M., Koike K. (2010) Gastric cancer cell line Hs746T harbors a splice site mutation of c-Met causing juxtamembrane domain deletion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 394, 1042–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rodrigues G. A., Naujokas M. A., Park M. (1991) Alternative splicing generates isoforms of the Met receptor tyrosine kinase which undergo differential processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 2962–2970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., Speleman F. (2002) Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3, RESEARCH0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christensen J. G., Schreck R., Burrows J., Kuruganti P., Chan E., Le P., Chen J., Wang X., Ruslim L., Blake R., Lipson K. E., Ramphal J., Do S., Cui J. J., Cherrington J. M., Mendel D. B. (2003) A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met kinase inhibits c-Met-dependent phenotypes in vitro and exhibits cytoreductive antitumor activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 63, 7345–7355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bao J., Gur G., Yarden Y. (2003) Src promotes destruction of c-Cbl: implications for oncogenic synergy between Src and growth factor receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2438–2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ponzetto C., Bardelli A., Zhen Z., Maina F., dalla Zonca P., Giordano S., Graziani A., Panayotou G., Comoglio P. M. (1994) A multifunctional docking site mediates signaling and transformation by the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor family. Cell 77, 261–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ettenberg S. A., Magnifico A., Cuello M., Nau M. M., Rubinstein Y. R., Yarden Y., Weissman A. M., Lipkowitz S. (2001) Cbl-b-dependent coordinated degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor signaling complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27677–27684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Swaminathan G., Tsygankov A. Y. (2006) The Cbl family proteins: ring leaders in regulation of cell signaling. J. Cell. Physiol. 209, 21–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lai A. Z., Abella J. V., Park M. (2009) Cross-talk in Met receptor oncogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 19, 542–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ryan P. E., Davies G. C., Nau M. M., Lipkowitz S. (2006) Regulating the regulator: negative regulation of Cbl ubiquitin ligases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Feshchenko E. A., Langdon W. Y., Tsygankov A. Y. (1998) Fyn, Yes, and Syk phosphorylation sites in c-Cbl map to the same tyrosine residues that become phosphorylated in activated T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 8323–8331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang Y., Yeung Y. G., Stanley E. R. (1999) CSF-1 stimulated multiubiquitination of the CSF-1 receptor and of Cbl follows their tyrosine phosphorylation and association with other signaling proteins. J. Cell. Biochem. 72, 119–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Ettenberg S. A., Katz M., Tsygankov A. Y., Alroy I., Lavi S., Iwai K., Reiss Y., Ciechanover A., Lipkowitz S., Yarden Y. (1999) Ubiquitin ligase activity and tyrosine phosphorylation underlie suppression of growth factor signaling by c-Cbl/Sli-1. Mol. Cell 4, 1029–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kassenbrock C. K., Anderson S. M. (2004) Regulation of ubiquitin protein ligase activity in c-Cbl by phosphorylation-induced conformational change and constitutive activation by tyrosine to glutamate point mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28017–28027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bisson S. A., Ujack E. E., Robbins S. M. (2002) Isolation and characterization of a novel, transforming allele of the c-Cbl proto-oncogene from a murine macrophage cell line. Oncogene 21, 3677–3687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kales S. C., Ryan P. E., Nau M. M., Lipkowitz S. (2010) Cbl and human myeloid neoplasms: the Cbl oncogene comes of age. Cancer Res. 70, 4789–4794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Makishima H., Cazzolli H., Szpurka H., Dunbar A., Tiu R., Huh J., Muramatsu H., O'Keefe C., Hsi E., Paquette R. L., Kojima S., List A. F., Sekeres M. A., McDevitt M. A., Maciejewski J. P. (2009) Mutations of e3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl family members constitute a novel common pathogenic lesion in myeloid malignancies. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 6109–6116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tan Y. H., Krishnaswamy S., Nandi S., Kanteti R., Vora S., Onel K., Hasina R., Lo F. Y., El-Hashani E., Cervantes G., Robinson M., Hsu H. S., Kales S. C., Lipkowitz S., Karrison T., Sattler M., Vokes E. E., Wang Y. C., Salgia R. (2010) CBL is frequently altered in lung cancers: its relationship to mutations in MET and EGFR tyrosine kinases. PLoS One 5, e8972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Naramura M., Nadeau S., Mohapatra B., Ahmad G., Mukhopadhyay C., Sattler M., Raja S. M., Natarajan A., Band V., Band H. (2011) Mutant Cbl proteins as oncogenic drivers in myeloproliferative disorders. Oncotarget 2, 245–250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McLean L. A., Gathmann I., Capdeville R., Polymeropoulos M. H., Dressman M. (2004) Pharmacogenomic analysis of cytogenetic response in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rodrigues G. A., Park M. (1993) Dimerization mediated through a leucine zipper activates the oncogenic potential of the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 6711–6722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ponzo M. G., Lesurf R., Petkiewicz S., O'Malley F. P., Pinnaduwage D., Andrulis I. L., Bull S. B., Chughtai N., Zuo D., Souleimanova M., Germain D., Omeroglu A., Cardiff R. D., Hallett M., Park M. (2009) Met induces mammary tumors with diverse histologies and is associated with poor outcome and human basal breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12903–12908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lo F. Y., Tan Y. H., Cheng H. C., Salgia R., Wang Y. C. (2011) An E3 ubiquitin ligase, c-Cbl: a new therapeutic target of lung cancer. Cancer 117, 5344–5350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.