Background: The molecular pathogenesis of fukutin-deficient dystroglycanopathy remains unclear, and no effective treatment is available.

Results: Some disease-causing missense fukutin mutants showed mislocalization in cultured cells, which can be corrected by treatments directed at folding amelioration.

Conclusion: Correction of cellular localization of disease-causing mutants may have a therapeutic benefit.

Significance: A possible therapeutic strategy for fukutin-deficient dystroglycanopathy is proposed based on its molecular pathogenesis.

Keywords: Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Golgi, Muscular Dystrophy, Mutant, Pathogenesis, Fukuyama-type Muscular Dystrophy, α-Dystroglycan, Dystroglycanopathy, Fukutin, Mislocalization

Abstract

Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD), the second most common childhood muscular dystrophy in Japan, is caused by alterations in the fukutin gene. Mutations in fukutin cause abnormal glycosylation of α-dystroglycan, a cell surface laminin receptor; however, the exact function and pathophysiological role of fukutin are unclear. Although the most prevalent mutation in Japan is a founder retrotransposal insertion, point mutations leading to abnormal glycosylation of α-dystroglycan have been reported, both in Japan and elsewhere. To understand better the molecular pathogenesis of fukutin-deficient muscular dystrophies, we constructed 13 disease-causing missense fukutin mutations and examined their pathological impact on cellular localization and α-dystroglycan glycosylation. When expressed in C2C12 myoblast cells, wild-type fukutin localizes to the Golgi apparatus, whereas the missense mutants A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C instead accumulated in the endoplasmic reticulum. Protein O-mannose β1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 (POMGnT1) also mislocalizes when co-expressed with these missense mutants. The results of nocodazole and brefeldin A experiments suggested that these mutant proteins were not transported to the Golgi via the anterograde pathway. Furthermore, we found that low temperature culture or curcumin treatment corrected the subcellular location of these missense mutants. Expression studies using fukutin-null mouse embryonic stem cells showed that the activity responsible for generating the laminin-binding glycan of α-dystroglycan was retained in these mutants. Together, our results suggest that some disease-causing missense mutations cause abnormal folding and localization of fukutin protein, and therefore we propose that folding amelioration directed at correcting the cellular localization may provide a therapeutic benefit to glycosylation-deficient muscular dystrophies.

Introduction

Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD,2 MIM 253800) is the second most common childhood muscular dystrophy and one of the most prevalent autosomal recessive disorders in the Japanese population. FCMD is clinically characterized by congenital muscular dystrophy in combination with cortical dysgenesis (micropolygyria) and ocular abnormalities (1). We identified fukutin, the gene responsible for FCMD, on chromosome 9q31 by linkage analysis and positional cloning (2, 3). Most FCMD-bearing chromosomes have been derived from a single ancestral founder and have a 3-kb retrotransposal insertion in the 3′ noncoding region of the fukutin gene. Compound heterozygosity, with both a retrotransposal mutation and a point mutation in fukutin, is sometimes seen and generally exhibits more severe pathologies (4, 5). However, a recent report has identified several Japanese patients presenting with mild limb-girdle dystrophy (LGMD2M, MIM 611588) and normal intelligence (6) and who have a retrotransposal mutation and a point mutation in the fukutin gene. Outside Japan, fukutin mutations have been reported in patients with various phenotypes, from Walker-Warburg syndrome (WWS, MIM 236670) to LGMD (7–13). Overall, the current common understanding is that fukutin alterations can give rise to a wide spectrum of phenotypes.

Mutations in fukutin cause abnormal glycosylation of the cell surface laminin receptor α-dystroglycan (DG) and reduce its laminin binding activity (14). The α- and β-DG complex is believed to provide physical strength to the sarcolemma by connecting the basal lamina to the cytoskeleton. Thus, abnormal glycosylation caused by fukutin mutations underlies FCMD molecular pathogenesis, but the exact function of fukutin remains unclear. The fukutin gene encodes a 461-amino acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 53.7 kDa (3). Although endogenous fukutin protein has not been detected in cells, likely due to its low abundance, expression studies have proposed that fukutin gene product localizes to the Golgi apparatus (15, 16). Fukutin protein contains a transmembrane domain (3, 16), a putative N-glycosylation site (3), and a DxD motif that is predicted to modify cell surface glycoproteins or glycolipids (17). Previously, we showed that the transmembrane domain of fukutin binds to the protein O-mannose β1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 (POMGnT1), which is encoded by the responsible gene for muscle-eye-brain disease (MIM 253280) (18), suggesting that fukutin affects the enzymatic activity of POMGnT1 (16). Other regions of the fukutin protein share no sequence homology with known proteins. In addition to FCMD, several other forms of muscular dystrophy are caused by abnormal glycosylation of α-DG; together, these conditions are termed as “dystroglycanopathy.” To date, six genes (protein O-mannosyltransferase 1 (POMT1), protein O-mannosyltransferase 2 (POMT2), POMGnT1, fukutin, fukutin-related protein (FKRP), and LARGE) have been implicated in dystroglycanopathies, and all are thought to be involved in glycosylation of α-DG (19–23). POMGnT1 and the POMT1/2 complex are known to have glycosyltransferase activities directly involved in synthesis of O-mannosyl sugar chains on α-DG (18, 24). Quite recently, it has been shown that LARGE can act as a bifunctional glycosyltransferase with both xylosyltransferase and glucuronyltransferase activities (25). On the other hand, the exact function of FKRP is unknown. Yoshida-Moriguchi et al. reported that a phosphodiester-linked moiety on O-mannose of α-DG is defective in LARGE- or fukutin-deficient dystroglycanopathies (26). This finding suggests that LARGE and fukutin might be involved in the synthesis of the postphosphoryl modification, which is necessary for laminin binding activity.

The precise pathogenic mechanism of FCMD has remained obscure. In this report, to understand molecular pathogenesis of fukutin-deficient muscular dystrophies, we constructed 13 disease-causing missense fukutin mutations that have been reported inside and outside Japan (4–6, 9–13, 27, 28) and investigated their pathological roles in fukutin intracellular location. Four mutants (A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C) lost their Golgi localization and instead accumulated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) when expressed in C2C12 cultured cells. Using fukutin-null mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells, we showed that these mutants retain the activity responsible for α-DG glycosylation. Finally, we found that low temperature culture and curcumin treatment are effective in correcting the localization of these missense fukutin mutants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Brefeldin A (BFA) and nocodazole were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Curcumin was purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan).

Antibodies used in this study were as follows: monoclonal anti-V5 (Invitrogen), rabbit polyclonal anti-FLAG (Sigma), monoclonal anti-α-DG clone IIH6C4 (Millipore), monoclonal anti-β-DG clone 8D5 (Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK), monoclonal anti-GM130 (BD Biosciences), monoclonal anti-KDEL antibodies (Stressgen, Victoria, Canada); rabbit polyclonal anti-laminin (Sigma); and goat polyclonal antibody against the C-terminal region of α-DG (AP-074G-C) (29)

Vector Constructions and Site-directed Mutagenesis

For the construction of expression vectors, the coding regions of human POMGnT1, human fukutin, or human FKRP with a FLAG or a V5 epitope at the C terminus were cloned into the pEF1/V5-HisA vector (Invitrogen). Expression vectors encoding 13 different disease-causative missense fukutin mutants were constructed using site-directed mutagenesis. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Immunofluorescence Detection

Mouse myoblast C2C12 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Wako). Mouse ES cells were grown in DMEM with 15% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 μm 2-mercaptoethanol, and streptomycin. Targeted disruptions of the fukutin gene in ES cells have been described previously (30).

Cell transfection was performed using Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. 48 h after transfection, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then permeabilized in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Nacalai Tesque). For immunofluorescence detection, after blocking with 1% BSA (Wako) in PBS at room temperature for 1 h, the cells were first incubated for 90 min with polyclonal anti-FLAG, monoclonal anti-GM130, monoclonal anti-KDEL, or monoclonal anti-V5 antibodies, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and/or Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. After a final rinse with PBS, cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy using a Leica DMR microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

For BFA, nocodazole, or curcumin treatment, the cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml BFA or 10 μg/ml nocodazole for 2 h after 48 h of transfection, or 10 μg/ml curcumin for 24 h after 24 h of transfection. For statistical analysis of fukutin cellular localization, cells expressing fukutin were classified into four classes (Golgi localization, Golgi and around localization, dot localization, and ER localization) (see Fig. 6A). For statistical analysis of POMGnT1 localization, cells co-expressing fukutin/POMGnT1 were classified into three classes (Golgi localization with fukutin, Golgi localization without fukutin, and ER localization). The number of cells in each class was counted and analyzed using the χ2 test.

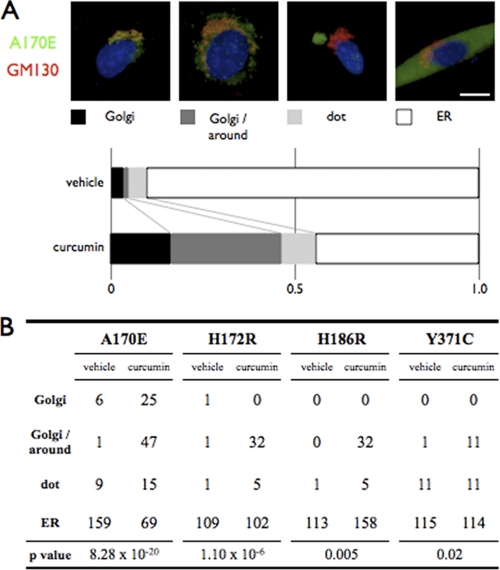

FIGURE 6.

Curcumin treatment partly corrects mislocalization of the missense fukutin mutants. A, effects of curcumin treatment on the cellular localization of the missense A170E fukutin mutants. C2C12 cells expressing the missense fukutin mutant A170E were cultured in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml curcumin. Cells were classified into four classes (Golgi localization, Golgi and around localization, dot localization, and ER localization), then counted and statistically analyzed using the χ2 test. Red, GM130; green, expressed missense fukutin protein A170E; blue, DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, statistical analysis of effects of curcumin treatment on the cellular localization of the missense fukutin mutants A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C.

Dystroglycan Preparation

DG was enriched from solubilized mouse ES cells. The ES cells were solubilized in 1 ml of PBS containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor mixture (Nacalai Tesque). Solubilized fractions were incubated with 30 μl of wheat germ agglutinin-agarose beads (Vector Laboratories) at 4 °C for 2 h. The beads were washed five times with 1 ml of PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor mixture, then directly boiled for 5 min in SDS-polyacrylamide gel loading buffer.

SDS-PAGE, Western Blotting, and Laminin Overlay Assay

Cell lysates were dissolved in SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE in 10% gels or 7.5% gels. Gels were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore), probed with anti-FLAG, anti-α-DG core protein (AP-074G-C), anti-α-DG sugar chain (IIH6C4), or anti-β-DG antibodies, and then developed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA). Blots were processed using ECL plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare) and exposed to Fuji RX-U x-ray film (Fuji Film, Kanagawa, Japan). The laminin overlay assay was performed according to the method of Michele et al. (14).

Additional methods are described under supplemental Experimental Procedure.

RESULTS

Mislocalization of Disease-causing Missense Mutant Fukutin Proteins

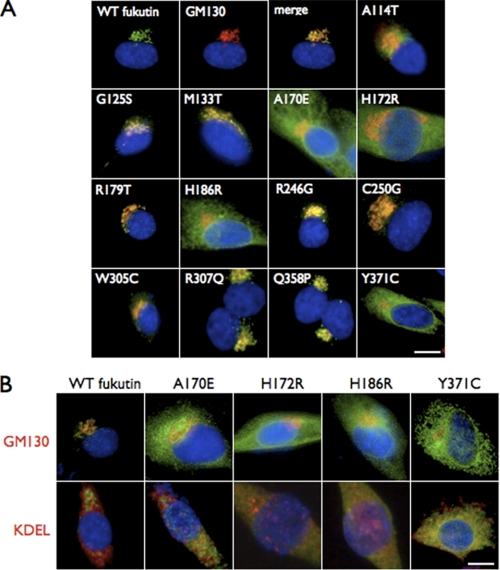

To examine the cellular location of fukutin proteins containing disease-causing missense mutations, we constructed expression vectors encoding wild-type or mutant fukutin proteins with a FLAG epitope at the C terminus. The missense mutants analyzed in this study have been identified inside and outside Japan (Table 1), and their clinical phenotypes vary from severe WWS-like to mild LGMD-type without mental retardation (Table 1 and Fig. 1). These constructs were transfected into C2C12 myoblast cells, and the cellular localizations of the expressed fukutin proteins were examined by immunofluorescence. Immunofluorescent signals indicated co-localization of the expressed wild-type fukutin with the Golgi apparatus marker GM130 (162/176 cells; Golgi + Golgi and around/total cells) (Fig. 2A, merge, and supplemental Table I). Nine of the 13 missense mutants (A114T (97/113), G125S (140/144), M133T (109/120), R179T (142/149), R246G (101/110), C250G (124/134), W305C (183/198), R307Q (131/134), and Q358P (174/182)) also co-localized with GM130 (supplemental Table I), indicating that these mutations do not affect the cellular location of fukutin protein. In contrast, the A170E (13/146), H172R (8/145), and H186R (6/141) mutants, as well as the previously reported Y371C (8/128) mutant (16), did not co-localize with GM130 (Fig. 2A and supplemental Table I), instead showing co-localization with the ER marker KDEL (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C aberrantly localize to the ER.

TABLE 1.

Disease-causing missense mutations in the fukutin gene

| Mutation | Other allele | Severity | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A114T | T286 frame shift | Mild | 10 |

| G125Sa | 5370–5842 deletion (3′-UTR) | Severe | 11 |

| G125Sa | F390 frame shift | Severe | 11 |

| M133T | 3-kb insertion | Typical | 28 |

| A170E | Y371C | Typical | 13 |

| H172R | 3-kb insertion | Typical | 27 |

| R179T | 3-kb insertion | Mild | 6 |

| H186R | Homozygote | Severe | 12 |

| R246G | R47 nonsense | Mild | 13 |

| C250G | 3-kb insertion | Typical | 4 |

| W305C | Homozygote | Typical | 10 |

| R307Q | Homozygote | Mild | 13 |

| R307Q | F390 frame shift | Mild | 9 |

| R307Q | N455 frame shift | Mild | 9 |

| Q358P | 3-kb insertion | Mild | 6 |

| Y371C | 3-kb insertion | Typical | 5 |

| Y371C | A170E | Typical | 13 |

a G125S has been registered as a polymorphism (rs_34006675).

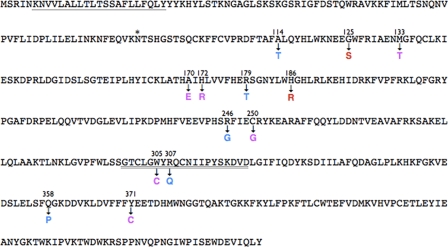

FIGURE 1.

Amino acid sequence of fukutin and location of missense mutations. Amino acid changes are indicated along with severity of phenotype. Blue, mild form (CMD without mental retardation, LGMD, or cardiomyopathy). Purple, typical form (FCMD, CMD with mental retardation); red, severe form (WWS). Single underline indicates the transmembrane domain, the asterisk indicates an N-glycosylation site, and the double underline indicates the DxD motif.

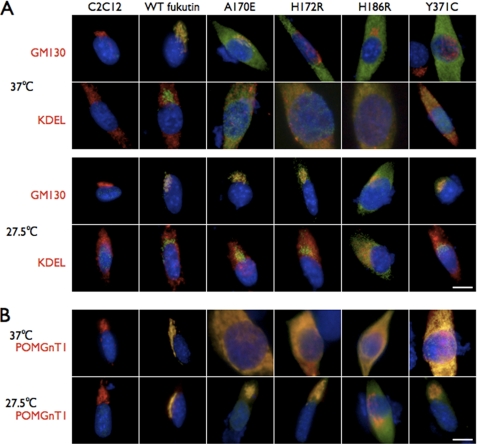

FIGURE 2.

Some disease-causing missense mutations cause abnormal cellular localization of fukutin. A, localization of the FLAG-tagged wild-type or missense fukutin proteins in transfected C2C12 myoblast cultured cells. Cells were double-labeled with anti-FLAG (green) and a Golgi marker GM130 (red). No co-localization was seen for the missense fukutin mutants A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C. Wild-type (WT fukutin) and the other nine mutants co-localized with GM130. B, mislocalization of missense fukutin mutants to the ER. The fukutin missense mutants A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C (green) lost their localization to the Golgi (red) in transfected C2C12 cultured cells (upper). Co-localization of these mutants with the ER marker KDEL (red) was seen in the cultures (lower). Blue, DAPI, indicating the nucleus. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Accumulation of Missense Fukutin Mutants in ER Caused by Impaired Transport to the Golgi

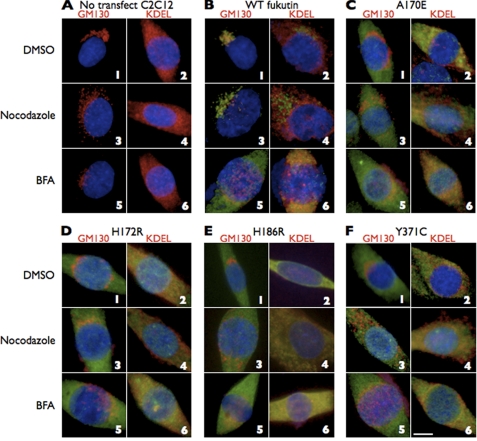

Accumulation of the four mutants in the ER might result from improper cellular trafficking. To determine whether the mutants are not properly transported from the ER to the Golgi or whether they are transported back to the ER after reaching the Golgi, we treated C2C12 cells expressing wild-type fukutin or the four mutants with nocodazole (an inhibitor for retrograde transport from the Golgi to the ER) or BFA (an inhibitor for anterograde transport from the ER to the Golgi). If the four mutants reached the Golgi and then were immediately transported back to the ER, the four mutant proteins should be detected in the Golgi after nocodazole treatment. Immunofluorescent signals indicating ER accumulation of the four mutants were observed following a 2-h incubation with 10 μg/ml nocodazole (Fig. 3C–F, panels 4). When cells expressing wild-type fukutin were incubated with 5 μg/ml BFA, the wild-type fukutin was detected in the ER (99/107; ER/total cells) (Fig. 3B, panel 6, and supplemental Table II), as seen in the cells expressing any of the four mutants. These data suggested that failure of proper transport via the anterograde pathway causes mislocalization of the four mutants to the ER.

FIGURE 3.

Accumulation of the missense mutants in the ER could be caused by the failure of proper transport via the anterograde pathway. C2C12 cells without (A) or with expression of wild-type fukutin (B) or the missense mutants (C–F) were incubated with nocodazole or BFA. Nocodazole treatment did not change the cellular localization of the expressed mutant fukutin proteins, whereas BFA treatment shifted wild-type fukutin to the ER. Red, GM130 or KDEL; green, expressed fukutin proteins; blue, DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Correction of Cellular Location of Mutant Fukutin Proteins by Low Temperature Culture

We hypothesized that mislocalization resulted from protein misfolding and therefore examined whether the localization of the four missense mutants could be corrected by folding amelioration. It has been reported that cell culture at low temperature can ameliorate folding and correct the subcellular localization of missense mutant proteins (31). In culture at 37 °C, the four missense fukutin mutants (A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C) were co-localized with KDEL (Fig. 4A). At low temperature (27.5 °C), the A170E (130/144; Golgi + Golgi and around/total cells), H172R (130/159), and Y371C (102/158) mutants preferentially co-localized with GM130 (Fig. 4A and supplemental Table I), indicating that the ER accumulation had decreased and proper localization to the Golgi was restored. Most of the expressed H186R mutant protein, however, remained in the ER (134/155; ER/total cells) at 27.5 °C; only a small proportion of this mutant shifted to the Golgi (Fig. 4A and supplemental Table I).

FIGURE 4.

Low temperature culture corrects mislocalization of mutant fukutin proteins. A, effects of low temperature culture on the localization of the missense fukutin mutants. At 37 °C, the missense fukutin mutants (A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C, green) co-localized with KDEL (ER marker, red) in C2C12 cultured cells (upper). In contrast, at 27.5 °C, the missense fukutin mutants A170E, H172R, and Y371C lost their co-localization with KDEL and acquired co-localization with GM130 (Golgi marker, red) (lower). A large amount of the mutant H186R protein retained the ER localization in 27.5 °C culture. B, POMGnT1 localization when co-expressed with the missense mutants. POMGnT1 (red) mislocalized to the ER when co-expressed with the missense fukutin mutants (A170E, H172R, H186R, or Y371C, green) at 37 °C. However, at 27.5 °C, localization of POMGnT1 was restored to the Golgi even when co-expressed with mutant fukutin proteins. Blue, DAPI. Scale bars, 10 μm.

POMGnT1, which has been shown to interact with fukutin and localize to the Golgi (151/156; Golgi with fukutin/total cells) (supplemental Table III) (16), also mislocalized to the ER when co-expressed with the mutants A170E (89/103; ER/total cells), H172R (102/113), H186R (96/111), and Y371C (98/109) (Fig. 4B, 37 °C, and supplemental Table III). These results indicated that fukutin mislocalization also affects the cellular location of POMGnT1. Low temperature culture of cells expressing both POMGnT1 and any of the mutants A170E (158/173; Golgi with fukutin/total cells), H172R (103/129), or Y371C (126/192) restored POMGnT1 subcellular localization to the Golgi (Fig. 4B, 27.5 °C, and supplemental Table III). When expressed with the H186R mutant, the POMGnT1 localization shifted to the Golgi despite the majority of the H186R mutant remaining in the ER (108/141; Golgi without fukutin/total cells) (Fig. 4B and supplemental Table III). These data showed that low temperature culture could correct mislocalization of the mutant fukutin proteins, but its effect may depend on the position of missense mutations within the protein.

Residual Function of Fukutin Missense Mutants to Restore α-Dystroglycan Glycosylation

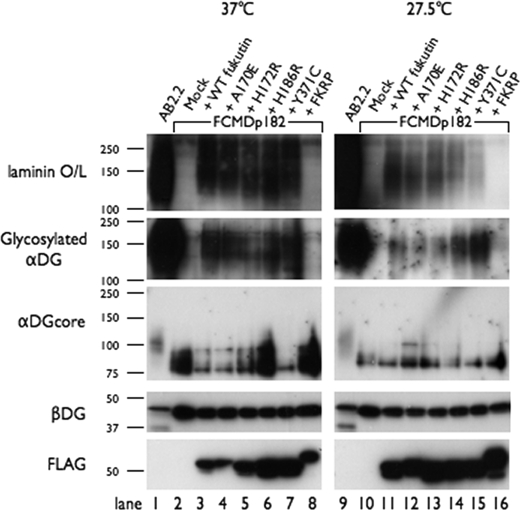

C2C12 cells contain endogenous fukutin, making it difficult to evaluate the α-DG modification activity of exogenously expressed mutant fukutin proteins. Instead, we used fukutin-null mouse ES cells (FCMDp182 cell) (30) to examine whether the four missense mutant fukutin proteins retain the activity responsible for α-DG modification. We expressed the four mutants (A170E, H172R, H186R, and Y371C) in FCMDp182 cells (supplemental Fig. 1) and then examined the recovery of glycosylation and laminin binding activity of α-DG. In mock-transfected FCMDp182 cells cultured at either 37 °C or 27.5 °C, α-DG showed no detectable reactivity against the monoclonal IIH6C4 antibody, which recognizes the functionally glycosylated form of α-DG. We also observed hypoglycosylation of α-DG, as indicated by lower molecular mass, and no α-DG laminin binding activity in mock-transfected cells (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 10). When wild-type fukutin was expressed in FCMDp182 cells, we observed restoration of the laminin binding activity and the IIH6C4 reactivity of α-DG, but at much weaker levels than for α-DG in the wild-type mouse ES cell line AB2.2 (lanes 1 and 3). This partial restoration and the faint amount of α-DG core protein bands around 100 kDa (the size of α-DG in the AB2.2 cells) may result from low transfection efficiency. Expression of each of the four missense mutants in the FCMDp182 cells restored the IIH6C4 reactivity and the laminin binding activity to levels comparable with those observed in the wild-type fukutin transfectants (lanes 3–7). Although these missense mutants preferentially localized to the ER at 37 °C, it is possible that small amounts of the expressed mutants reached the Golgi. To support this interpretation, a report has shown that the mislocalized mutant protein ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, which is the most common mutation leading to cystic fibrosis, shows partial function when overexpressed (32). We have not detected restoration of the IIH6C4 reactivity and the laminin binding activity by expression of a mutant fukutin protein with direct substitutions in the DxD motif (D317A/V/D319A) (supplemental Fig. 2). Expression of FKRP, a member of the fukutin protein family, in FCMDp182 cells showed no effect on α-DG glycosylation (lane 8). We also performed these experiments at low culture temperature (27.5 °C) and obtained similar results (Fig. 5, lanes 9–16). The reason for reduced efficiency of glycosylation recovery in low temperature culture is unclear, but the low temperature might affect enzymatic activities involved in the α-DG glycosylation pathway. Because the expression level of each mutant protein was different (Fig. 5, anti-FLAG), it was not possible to simply compare their residual activity. Importantly, however, all four mutants retained the activity responsible for α-DG modification.

FIGURE 5.

Fukutin missense mutants retain the activity responsible for α-DG glycosylation. Western blot analysis was performed to detect IIH6C4 (glycosylated α-DG), core α-DG, β-DG, and FLAG tag, and the laminin overlay assay. DG and fukutin proteins were prepared from wild-type mouse ES cells (AB2.2), fukutin-deficient mouse ES cells (FCMDp182), and fukutin- or FKRP-transfected FCMDp182 cells, and cultured at 37 °C and 27.5 °C. FCMDp182 cells expressing any of the mutant fukutin proteins showed levels of glycosylated α-DG signal (IIH6C4-reactivity) and laminin binding activity that were comparable with those observed in FCMDp182 cells expressing wild-type fukutin.

Correction of Mislocalization of Missense Fukutin Mutants by Curcumin Treatment

Our results indicated that mislocalization of some missense mutants could cause disease-related abnormal glycosylation of α-DG. Therefore, we next searched for chemicals that could restore proper localization. Curcumin, a nontoxic natural constituent of turmeric spice, has shown the ability to correct misfolding and mislocalization of the ΔF508 mutant (33). We incubated C2C12 cells expressing the four mutants (A170E, H172R, H186R, or Y371C) with 10 μg/ml curcumin at 37 °C for 24 h. Among the four mutants, the A170E mutant showed the greatest benefit from curcumin treatment. In the absence of curcumin, approximately 90% of the cells showed ER localization of the A170E mutant (159/175; ER/total cells), and only a few cells (7/175; Golgi + Golgi and around cells) showed Golgi localization (Fig. 6). Curcumin treatment significantly decreased the ER mislocalization signal of the A170E mutant (69/156; ER/total ells) and increased the Golgi- and Golgi/around signals (72/156; Golgi + Golgi and around cells) (p = 8.28 × 10−20). Although not as dramatic as seen with A170E, the other mutants showed slight beneficial changes in their cellular distributions following curcumin treatment (Fig. 6B and supplemental Table II). We also examined glycerol, arginine, and 17-allylaminogeldanamycin for beneficial effects on localization of the mutants, but none was observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have demonstrated that some disease-causing missense fukutin mutants lost their Golgi localization in C2C12 cultured cells and that this mislocalization can be corrected by low temperature culture or curcumin treatment. We identified four missense mutants that localized abnormally to the ER. Nocodazole treatment did not alter their ER localization, and low temperature culture shifted three of the four mutants to the Golgi. It is generally recognized that cell culture at low temperature can ameliorate protein misfolding and correct abnormal cellular localization (31). Therefore, we presume that some missense mutants could not be transported to the Golgi via the anterograde pathway because of protein misfolding caused by amino acid substitutions. A large amount of the fourth mutant protein, H186R, retained the ER localization even under low temperature conditions (Fig. 4A). It has been reported that the patient with the homozygous H186R mutation is affected with WWS (12), which shows more severe pathological features than typical FCMD. The H186R mutation in the fukutin gene may affect protein folding severely enough that low temperature conditions cannot correct mislocalization. We reported previously that POMGnT1 interacts with fukutin and co-localizes to the Golgi (16). Our present data show that correction of the mislocalization of the three missense fukutin mutants by low temperature culture was accompanied by correction of POMGnT1 cellular localization (Fig. 4B). This POMGnT1 behavior is rational because the transmembrane region of fukutin, through which fukutin binds to POMGnT1 (16), remained intact in these missense fukutin mutants (Fig. 1, single underline). Immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed the interaction between each of the missense fukutin mutants and POMGnT1 (supplemental Fig. 3). Most of the H186R mutant remained in the ER at 27.5 °C, but POMGnT1 expressed with the H186R localized to the Golgi. The reason for this result is uncertain, but a possible explanation is that the H186R mutant may have a harmful (dominant negative-like) effect on POMGnT1 localization, and this effect may be ameliorated at low temperature.

The above-mentioned four mutants, which showed abnormal localization to the ER, were identified in patients presenting with a typical or a severe phenotype. However, several of the remaining nine mutants, which showed Golgi localization, were also identified in patients presenting with the typical or the severe phenotype (G125S, M133T, C250G, and W305C) (Table 1). Therefore, the typical or severe phenotypes seem not always to be related to abnormal cellular localization of mutated proteins. Given that FCMD is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, disease-causing mutations in the fukutin gene must lead to loss of function of the fukutin protein. Although the exact function of fukutin is undetermined, these nine mutations may disrupt an important functional domain in the protein. For example, the W305C (10) and R307Q (9, 13) mutations are located in the DxD motif (Fig. 1, double underline), which is predicted to be involved in the modification of cell surface glycoproteins or glycolipids (17). These substitutions may disrupt the DxD motif and produce dysfunctional fukutin protein. Five mutations (A114T, R179T, R246G, R307Q, and Q358P) have been identified in patients presenting with mild phenotypes (congenital muscular dystrophy with no mental retardation, LGMD with no mental retardation, or cardiomyopathy) (6, 9, 10, 13). In the present study, these five mutant proteins were localized to the Golgi when expressed in C2C12 cells. In patients with R179T or Q358P mutations, α-DG shows residual reactivity against the monoclonal antibody IIH6C4, which recognizes functionally glycosylated α-DG (6), indicating that these fukutin mutations retain partial function in the DG maturation pathway.

It is of interest that some missense fukutin mutants retain α-DG glycosylation activity and that their mislocalization could be partly corrected by treatments directing at folding amelioration. These observations suggest that drugs capable of correcting the localization might have therapeutic benefits in patients who carry these missense fukutin mutants. Although approximately half of the cells expressing the A170E mutant retained the ER accumulation signals following curcumin treatment (Fig. 6), recent studies have indicated that even partial restoration of α-DG glycosylation can produce therapeutic effects (29). Efforts to identify more efficient folding amelioration reagents may lead to therapeutic strategies.

A large number of missense mutations have been identified in dystroglycanopathy. It has been reported that missense mutations in POMT1 and POMGnT1 compromise enzymatic activity in the gene products (18, 34, 35). Disease-causing missense mutations in POMT2, LARGE, and FKRP have been also identified (10, 21–23, 36, 37). Recently, Kawahara et al. have reported that expression of some disease-causing missense FKRP mutant proteins in FKRP knock-down zebrafish restores α-DG glycosylation, suggesting a residual FKRP function in these missense mutants (38); however, phenotype improvement depends on the location of the mutation. The FKRP missense mutations C318Y and A455D, which failed to improve the fish phenotype in the report from Kawahara et al. (38), were reported to show abnormal cellular localization when expressed in certain cell lines (39). On the other hand, using several different cell lines, Dolatshad et al. suggested that a reduced protein (putative enzymatic) function of FKRP rather than protein mislocalization is the primary mechanism of disease (39). Interestingly, Bao et al. have reported cells lacking FKRP transcripts but expressing IIH6C4-reactive α-DG (40). This finding may indicate a possibility of a FKRP-independent glycosylation pathway. Alternatively, only a subtle amount of FKRP, even below detectable level by RT-PCR, may be sufficient for α-DG glycosylation. This implies that some missense mutants can restore IIH6C4-reactive α-DG if only a little protein function remains. Of the increasing number of identified disease-causing missense mutations, some may alter the cellular location of the protein, which can be a direct cause of disease. Correction of cellular localization or folding amelioration may have a therapeutic benefit for dystroglycanopathies caused by missense mutations, although the finding from cell culture experiments must be interpreted cautiously when extrapolating to human disease.

In this study, we have used curcumin to correct mislocalization of missense fukutin mutants. It has been reported that curcumin can correct misfolding and mislocalization of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator with the ΔF508 mutation (33). Curcumin has also been reported to have protective effects in neurodegenerative diseases by inhibiting protein misfolding and aggregation in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and Parkinson disease (41, 42). These studies indicate that curcumin or its derivatives might be new candidate compounds for protein-folding diseases. In addition, the use of pharmacological chaperones to stabilize or promote correct folding of mutant proteins has been shown as a potential therapeutic approach to phenylketonuria, in which more than 500 disease-causing mutations have been identified (43). Our results contribute to a deeper understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of fukutin-deficient muscular dystrophy and have led us to propose a novel therapeutic strategy directed at correction of cellular localization and/or folding amelioration of disease-causing missense mutant proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank past and present members of the Dr. Toda's laboratory for fruitful discussions and scientific contributions and Dr. Jennifer Logan for help in editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan Intramural Research Grant for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders of National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry 23B-5 and Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H20-016), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (A) 23249049 (to T. T.), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-aid for Young Scientists (B) 18790220 (to M. T.), Takeda Science Foundation (to M. K.), and Global COE (Centers of Excellence) Program Frontier Biomedical Science Underlying Organelle Network Biology.

This article contains supplemental Tables I–III, Experimental Procedures, and Figs. 1–3.

- FCMD

- Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- DG

- dystroglycan

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- FKRP

- fukutin-related protein

- LGMD

- limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

- POMGnT1

- protein O-mannose β1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1

- POMT1

- protein O-mannosyltransferase 1

- POMT2

- protein O-mannosyltransferase 2

- WWS

- Walker-Warburg syndrome.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fukuyama Y., Osawa M., Suzuki H. (1981) Congenital progressive muscular dystrophy of the Fukuyama type: clinical, genetic and pathological considerations. Brain Dev. 3, 1–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toda T., Segawa M., Nomura Y., Nonaka I., Masuda K., Ishihara T., Sakai M., Tomita I., Origuchi Y., Ohno K., Misugi N., Sasaki Y., Takada K., Kawai M., Otani K., Murakami T., Saito K., Fukuyama Y., Shimizu T., Kanazawa I., Nakamura Y. (1993) Localization of a gene for Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy to chromosome 9q31–33. Nat. Genet. 5, 283–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kobayashi K., Nakahori Y., Miyake M., Matsumura K., Kondo-Iida E., Nomura Y., Segawa M., Yoshioka M., Saito K., Osawa M., Hamano K., Sakakihara Y., Nonaka I., Nakagome Y., Kanazawa I., Nakamura Y., Tokunaga K., Toda T. (1998) An ancient retrotransposal insertion causes Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy. Nature 394, 388–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kondo-Iida E., Kobayashi K., Watanabe M., Sasaki J., Kumagai T., Koide H., Saito K., Osawa M., Nakamura Y., Toda T. (1999) Novel mutations and genotype-phenotype relationships in 107 families with Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD). Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 2303–2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kobayashi K., Sasaki J., Kondo-Iida E., Fukuda Y., Kinoshita M., Sunada Y., Nakamura Y., Toda T. (2001) Structural organization, complete genomic sequences and mutational analyses of the Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy gene, fukutin. FEBS Lett. 489, 192–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murakami T., Hayashi Y. K., Noguchi S., Ogawa M., Nonaka I., Tanabe Y., Ogino M., Takada F., Eriguchi M., Kotooka N., Campbell K. P., Osawa M., Nishino I. (2006) Fukutin gene mutations cause dilated cardiomyopathy with minimal muscle weakness. Ann. Neurol. 60, 597–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Silan F., Yoshioka M., Kobayashi K., Simsek E., Tunc M., Alper M., Cam M., Guven A., Fukuda Y., Kinoshita M., Kocabay K., Toda T. (2003) A new mutation of the fukutin gene in a non-Japanese patient. Ann. Neurol. 53, 392–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Bernabé D. B., van Bokhoven H., van Beusekom E., Van den Akker W., Kant S., Dobyns W. B., Cormand B., Currier S., Hamel B., Talim B., Topaloglu H., Brunner H. G. (2003) A homozygous nonsense mutation in the fukutin gene causes a Walker-Warburg syndrome phenotype. J. Med. Genet. 40, 845–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Godfrey C., Escolar D., Brockington M., Clement E. M., Mein R., Jimenez-Mallebrera C., Torelli S., Feng L., Brown S. C., Sewry C. A., Rutherford M., Shapira Y., Abbs S., Muntoni F. (2006) Fukutin gene mutations in steroid-responsive limb girdle muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 60, 603–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Godfrey C., Clement E., Mein R., Brockington M., Smith J., Talim B., Straub V., Robb S., Quinlivan R., Feng L., Jimenez-Mallebrera C., Mercuri E., Manzur A. Y., Kinali M., Torelli S., Brown S. C., Sewry C. A., Bushby K., Topaloglu H., North K., Abbs S., Muntoni F. (2007) Refining genotype phenotype correlations in muscular dystrophies with defective glycosylation of dystroglycan. Brain 130, 2725–2735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cotarelo R. P., Valero M. C., Prados B., Peña A., Rodríguez L., Fano O., Marco J. J., Martínez-Frías M. L., Cruces J. (2008) Two new patients bearing mutations in the fukutin gene confirm the relevance of this gene in Walker-Warburg syndrome. Clin. Genet. 73, 139–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Manzini M. C., Gleason D., Chang B. S., Hill R. S., Barry B. J., Partlow J. N., Poduri A., Currier S., Galvin-Parton P., Shapiro L. R., Schmidt K., Davis J. G., Basel-Vanagaite L., Seidahmed M. Z., Salih M. A., Dobyns W. B., Walsh C. A. (2008) Ethnically diverse causes of Walker-Warburg syndrome (WWS): FCMD mutations are a more common cause of WWS outside of the Middle East. Hum. Mutat. 29, E231-E241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vuillaumier-Barrot S., Quijano-Roy S., Bouchet-Seraphin C., Maugenre S., Peudenier S., Van den Bergh P., Marcorelles P., Avila-Smirnow D., Chelbi M., Romero N. B., Carlier R. Y., Estournet B., Guicheney P., Seta N. (2009) Four Caucasian patients with mutations in the fukutin gene and variable clinical phenotype. Neuromuscul. Disord. 19, 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Michele D. E., Barresi R., Kanagawa M., Saito F., Cohn R. D., Satz J. S., Dollar J., Nishino I., Kelley R. I., Somer H., Straub V., Mathews K. D., Moore S. A., Campbell K. P. (2002) Post-translational disruption of dystroglycan-ligand interactions in congenital muscular dystrophies. Nature 418, 417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matsumoto H., Noguchi S., Sugie K., Ogawa M., Murayama K., Hayashi Y. K., Nishino I. (2004) Subcellular localization of fukutin and fukutin-related protein in muscle cells. J. Biochem. 135, 709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xiong H., Kobayashi K., Tachikawa M., Manya H., Takeda S., Chiyonobu T., Fujikake N., Wang F., Nishimoto A., Morris G. E., Nagai Y., Kanagawa M., Endo T., Toda T. (2006) Molecular interaction between fukutin and POMGnT1 in the glycosylation pathway of α-dystroglycan. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350, 935–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aravind L., Koonin E. V. (1999) The fukutin protein family: predicted enzymes modifying cell surface molecules. Curr. Biol. 9, R836–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoshida A., Kobayashi K., Manya H., Taniguchi K., Kano H., Mizuno M., Inazu T., Mitsuhashi H., Takahashi S., Takeuchi M., Herrmann R., Straub V., Talim B., Voit T., Topaloglu H., Toda T., Endo T. (2001) Muscular dystrophy and neuronal migration disorder caused by mutations in a glycosyltransferase, POMGnT1. Dev. Cell 1, 717–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beltrán-Valero de Bernabé D., Currier S., Steinbrecher A., Celli J., van Beusekom E., van der Zwaag B., Kayserili H., Merlini L., Chitayat D., Dobyns W. B., Cormand B., Lehesjoki A. E., Cruces J., Voit T., Walsh C. A., van Bokhoven H., Brunner H. G. (2002) Mutations in the O-mannosyltransferase gene POMT1 give rise to the severe neuronal migration disorder Walker-Warburg syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 1033–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van Reeuwijk J., Janssen M., van den Elzen C., Beltran-Valero de Bernabé D., Sabatelli P., Merlini L., Boon M., Scheffer H., Brockington M., Muntoni F., Huynen M. A., Verrips A., Walsh C. A., Barth P. G., Brunner H. G., van Bokhoven H. (2005) POMT2 mutations cause α-dystroglycan hypoglycosylation and Walker-Warburg syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 42, 907–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brockington M., Blake D. J., Prandini P., Brown S. C., Torelli S., Benson M. A., Ponting C. P., Estournet B., Romero N. B., Mercuri E., Voit T., Sewry C. A., Guicheney P., Muntoni F. (2001) Mutations in the fukutin-related protein gene (FKRP) cause a form of congenital muscular dystrophy with secondary laminin α2 deficiency and abnormal glycosylation of α-dystroglycan. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 1198–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brockington M., Yuva Y., Prandini P., Brown S. C., Torelli S., Benson M. A., Herrmann R., Anderson L. V., Bashir R., Burgunder J. M., Fallet S., Romero N., Fardeau M., Straub V., Storey G., Pollitt C., Richard I., Sewry C. A., Bushby K., Voit T., Blake D. J., Muntoni F. (2001) Mutations in the fukutin-related protein gene (FKRP) identify limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2I as a milder allelic variant of congenital muscular dystrophy MDC1C. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 2851–2859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Longman C., Brockington M., Torelli S., Jimenez-Mallebrera C., Kennedy C., Khalil N., Feng L., Saran R. K., Voit T., Merlini L., Sewry C. A., Brown S. C., Muntoni F. (2003) Mutations in the human LARGE gene cause MDC1D, a novel form of congenital muscular dystrophy with severe mental retardation and abnormal glycosylation of α-dystroglycan. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2853–2861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manya H., Chiba A., Yoshida A., Wang X., Chiba Y., Jigami Y., Margolis R. U., Endo T. (2004) Demonstration of mammalian protein O-mannosyltransferase activity: co-expression of POMT1 and POMT2 required for enzymatic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 500–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inamori K., Yoshida-Moriguchi T., Hara Y., Anderson M. E., Yu L., Campbell K. P. (2012) Dystroglycan function requires xylosyl- and glucuronyltransferase activities of LARGE. Science 335, 93–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoshida-Moriguchi T., Yu L., Stalnaker S. H., Davis S., Kunz S., Madson M., Oldstone M. B., Schachter H., Wells L., Campbell K. P. (2010) O-mannosyl phosphorylation of α-dystroglycan is required for laminin binding. Science 327, 88–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matsumoto H., Hayashi Y. K., Kim D. S., Ogawa M., Murakami T., Noguchi S., Nonaka I., Nakazawa T., Matsuo T., Futagami S., Campbell K. P., Nishino I. (2005) Congenital muscular dystrophy with glycosylation defects of α-dystroglycan in Japan. Neuromuscul. Disord. 15, 342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoshioka M., Higuchi Y., Fujii T., Aiba H., Toda T. (2008) Seizure-genotype relationship in Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy. Brain Dev. 30, 59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kanagawa M., Nishimoto A., Chiyonobu T., Takeda S., Miyagoe-Suzuki Y., Wang F., Fujikake N., Taniguchi M., Lu Z., Tachikawa M., Nagai Y., Tashiro F., Miyazaki J., Tajima Y., Takeda S., Endo T., Kobayashi K., Campbell K. P., Toda T. (2009) Residual laminin binding activity and enhanced dystroglycan glycosylation by LARGE in novel model mice to dystroglycanopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 621–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Takeda S., Kondo M., Sasaki J., Kurahashi H., Kano H., Arai K., Misaki K., Fukui T., Kobayashi K., Tachikawa M., Imamura M., Nakamura Y., Shimizu T., Murakami T., Sunada Y., Fujikado T., Matsumura K., Terashima T., Toda T. (2003) Fukutin is required for maintenance of muscle integrity, cortical histiogenesis, and normal eye development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1449–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Denning G. M., Anderson M. P., Amara J. F., Marshall J., Smith A. E., Welsh M. J. (1992) Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature 358, 761–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng S. H., Fang S. L., Zabner J., Marshall J., Piraino S., Schiavi S. C., Jefferson D. M., Welsh M. J., Smith A. E. (1995) Functional activation of the cystic fibrosis trafficking mutant ΔF508-CFTR by overexpression. Am. J. Physiol. 268, L615–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Egan M. E., Pearson M., Weiner S. A., Rajendran V., Rubin D., Glöckner-Pagel J., Canny S., Du K., Lukacs G. L., Caplan M. J. (2004) Curcumin, a major constituent of turmeric, corrects cystic fibrosis defects. Science 304, 600–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Manya H., Sakai K., Kobayashi K., Taniguchi K., Kawakita M., Toda T., Endo T. (2003) Loss-of-function of an N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, POMGnT1, in muscle-eye-brain disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 306, 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Akasaka-Manya K., Manya H., Endo T. (2004) Mutations of the POMT1 gene found in patients with Walker-Warburg syndrome lead to a defect of protein O-mannosylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325, 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brockington M., Torelli S., Prandini P., Boito C., Dolatshad N. F., Longman C., Brown S. C., Muntoni F. (2005) Localization and functional analysis of the LARGE family of glycosyltransferases: significance for muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 657–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keramaris-Vrantsis E., Lu P. J., Doran T., Zillmer A., Ashar J., Esapa C. T., Benson M. A., Blake D. J., Rosenfeld J., Lu Q. L. (2007) Fukutin-related protein localizes to the Golgi apparatus and mutations lead to mislocalization in muscle in vivo. Muscle Nerve 36, 455–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kawahara G., Guyon J. R., Nakamura Y., Kunkel L. M. (2010) Zebrafish models for human FKRP muscular dystrophies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 623–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dolatshad N. F., Brockington M., Torelli S., Skordis L., Wever U., Wells D. J., Muntoni F., Brown S. C. (2005) Mutated fukutin-related protein (FKRP) localizes as wild type in differentiated muscle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 309, 370–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bao X., Kobayashi M., Hatakeyama S., Angata K., Gullberg D., Nakayama J., Fukuda M. N., Fukuda M. (2009) Tumor suppressor function of laminin-binding α-dystroglycan requires a distinct β3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 12109–12114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hafner-Bratkovic I., Gaspersic J., Smid L. M., Bresjanac M., Jerala R. (2008) Curcumin binds to the α-helical intermediate and to the amyloid form of prion protein: a new mechanism for the inhibition of PrP(Sc) accumulation. J. Neurochem. 104, 1553–1564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ono K., Yamada M. (2006) Antioxidant compounds have potent anti-fibrillogenic and fibril-destabilizing effects for α-synuclein fibrils in vitro. J. Neurochem. 97, 105–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pey A. L., Ying M., Cremades N., Velazquez-Campoy A., Scherer T., Thöny B., Sancho J., Martinez A. (2008) Identification of pharmacological chaperones as potential therapeutic agents to treat phenylketonuria. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 2858–2867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.