Abstract

Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic (AAP) bacteria are photoheterotrophic microbes that are found in a broad range of aquatic environments. Although potentially significant to the microbial ecology and biogeochemistry of marine ecosystems, their abundance and genetic diversity and the environmental variables that regulate these properties are poorly understood. Using samples along nearshore/offshore transects from five disparate islands in the Pacific Ocean (Oahu, Molokai, Futuna, Aniwa, and Lord Howe) and off California, we show that AAP bacteria, as quantified by the pufM gene biomarker, are most abundant near shore and in areas with high chlorophyll or Synechococcus abundance. These AAP bacterial populations are genetically diverse, with most members belonging to the alpha- or gammaproteobacterial groups and with subclades that are associated with specific environmental variables. The genetic diversity of AAP bacteria is structured along the nearshore/offshore transects in relation to environmental variables, and uncultured pufM gene libraries suggest that nearshore communities are distinct from those offshore. AAP bacterial communities are also genetically distinct between islands, such that the stations that are most distantly separated are the most genetically distinct. Together, these results demonstrate that environmental variables regulate both the abundance and diversity of AAP bacteria but that endemism may also be a contributing factor in structuring these communities.

INTRODUCTION

Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic (AAP) bacteria are photoheterotrophic microbes, a group whose members use both organic substrates and light energy for their carbon and energy requirements, and they are found in a diverse range of aquatic environments. AAP bacteria harvest light with the pigment bacteriochlorophyll a (BChl a), a distinct form of chlorophyll a not found in oxygenic photosynthetic microbes and also not readily quantified. Therefore, although potentially important, their abundance, ecology, and contribution to the carbon cycle are not well understood (24, 25, 43). Genomic evidence and physiological characterization have shown AAP bacteria to have diverse physiologies and metabolic potentials, including nitrification, carbon dioxide fixation, utilization of low-molecular-weight organic carbon, growth optimization on complex organic carbon sources, light-enhanced cellular growth, a preference for suboxic environments, and large amounts of carotenoids (12–14, 32). These characteristics may confer an advantage in inhabiting a wide variety of habitats with great environmental variability.

AAP bacteria have been found in a range of aquatic environments, including freshwater environments, marine environments, soil, hot springs, Antarctic lakes, and hydrothermal vents (11, 28, 43, 59). In the marine environment, they typically account for <1 to 3% of the total prokaryotic abundance (49) and have been found in both coastal and open ocean environments, including brackish waters (7, 8, 50). However, the abundance of AAP bacteria can range more dramatically (15, 27), and in some coastal mesotrophic estuaries, the abundance of AAP bacteria often exceeds 10% (49, 54). These high abundances may be driven by the association of AAP bacteria with particles that are often numerous in these environments (9, 30), but AAP bacteria are positively correlated with chlorophyll a in a variety of environments, suggesting that productivity may also drive their abundance (21, 63). In two eutrophic estuaries, light attenuation, nitrate, and ammonium are also positively correlated with AAP bacteria, further supporting a link with productivity or its associated particles (55). However, AAP bacteria account for nearly 25% of the total prokaryotic population in the hyperoligotrophic South Pacific Ocean (29), suggesting that other environmental variables may also be important and that there is a broad range of potential ecological niches for these microbes.

AAP bacteria are members of the Proteobacteria phylum of bacteria, and based on genomic and other single-locus evidence, they are closely related to anaerobic photosynthetic bacteria that also contain BChl (5, 58). Evidence from culture-dependent and -independent studies has shown AAP bacteria to be broadly genetically diverse, with members in the Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria subclasses (4, 46). Phylogenetic relationships among small-subunit (SSU) rRNA genes and core photosynthetic marker genes, including the pufM gene, are incongruent, suggesting that lateral transfer of the photosynthesis superoperon has produced a highly diverse population of organisms with the same photosynthetic system and pigments (39, 59). Both targeted (21, 55, 61) and nontargeted (62) metagenomic studies have shown that depending on the location and environment, members of either the Alpha- or Gammaproteobacteria subclass typically dominate the AAP bacterial community. For example, in the Baltic Sea, most AAP bacteria were gammaproteobacteria (37), while in the Global Ocean Sampling (GOS) expedition, the Roseobacter-like group of alphaproteobacteria dominated the oligotrophic AAP bacterial community (62). In addition, the GOS expedition revealed additional groups throughout the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans that have not been cultured. Thus, AAP bacteria are now known to be far more genetically diverse than originally thought (26).

Evidence from observations throughout the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans suggests that the abundance and diversity of AAP bacteria are structured along environmental gradients. For example, coastal and brackish waters appear to have unique clades of AAP bacteria not found in the open ocean (62). Similarly, waters with higher productivity, as indicated by high chlorophyll a concentrations, have lower AAP bacterial diversity than more oligotrophic waters (21). Conversely, there are no significant differences between free-living and particle-attached AAP bacteria for a given sampling location in some major estuaries, but among sampling locations, there are significant differences in genetic diversity (9). There is also substantial genetic variability among AAP bacterial samples from different locations in the Baltic Sea, including both fresh- and saltwater clades (37, 46), further suggesting that AAP bacteria are genetically diverse and that this diversity has biogeographic and potentially phylogeographic patterns related to environmental variables. These prior results show that while environmental variation may be important, there may also be endemism of AAP bacteria consistent with some of the original hypotheses of island biogeography (35), suggesting that geographic distance may play an important role in the ecological structuring of these microbial populations even though there are no apparent limitations to planktonic dispersal in the oceans.

To test these hypotheses, we measured the abundance of AAP bacteria by quantitative PCR (qPCR) amplification of the pufM marker gene along coastal environmental gradients at several locations throughout the Pacific Ocean and over time at one location to assess the variability of this photoheterotrophic bacterial population and to examine some of the environmental variables that may be controlling it. The genetic biodiversity of AAP bacteria, as assessed by the genetic diversity of the pufM gene, was compared along these gradients and between locations to explore the richness (alpha genetic diversity) and level of endemism (beta genetic diversity) of AAP bacterial populations. Like the SSU rRNA gene, the pufM gene is found in all AAP bacteria and has both conserved and variable regions, making it an excellent molecular marker for quantifying the abundance and assessing the genetic diversity of AAP bacteria (1, 49). We show that AAP bacteria are most abundant near shore and that this is strongly correlated with chlorophyll and Synechococcus abundance. AAP bacterial populations are genetically diverse, and this diversity is also correlated with environmental variables and location, suggesting that both population abundance and genetic diversity are regulated by a combination of environmental variables and endemism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

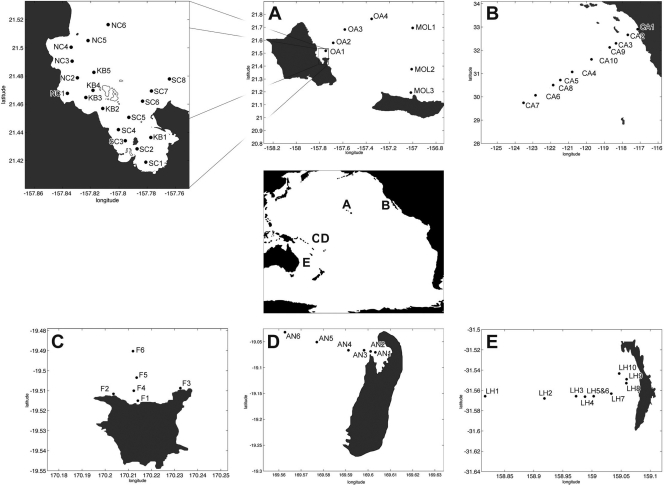

Sampling of eight nearshore/offshore transects was conducted in the Pacific Ocean at the following locations: California (28.60°N, 125.07°W), Aniwa (18.17°S, 169.25°E), Lord Howe (31.55°S, 159.08°E), Futuna (19.53°S, 170.22°E), Oahu (21.47°N, 157.98°W), Molokai (21.13°N, 157.03°W), and two locations in Kaneohe Bay, located on the island of Oahu (21.46°N, 157.80°W). Surface water samples were collected in opaque amber bottles for measurements of chlorophyll, salinity, nutrients, and DNA and for flow cytometry. Two of the nearshore/offshore transects, located in Kaneohe Bay, were sampled three times (13 June 2006, 4 August 2006, and 21 June 2007) (Fig. 1). In addition to surface samples, two depth profiles were measured using samples collected with Niskin bottles mounted to a conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD)-equipped oceanographic rosette.

Fig 1.

Locations of sampling stations. (A) Islands of Oahu and Molokai (HI), with an expanded view of Kaneohe Bay (inset); (B) California; (C) Island of Futuna; (D) Island of Aniwa; (E) Lord Howe Island.

Environmental data and DNA.

Temperature was recorded using a handheld digital thermometer for Aniwa, Futuna, and Kaneohe Bay transects. Kaneohe Bay salinity measurements were made in duplicate using a refractometer. Temperature and salinity measurements for California, Oahu, and Molokai transects were made using a calibrated CTD device. Size-fractionated (0.22 or 2.0 μm) chlorophyll concentrations were measured by vacuum (<100 mm Hg) filtering 100-ml samples through polycarbonate filters, with extraction in 100% methanol (MeOH) at −20°C in the dark for >24 h (18). Fluorescence was measured using a Turner Designs 10-AU fluorometer (56) that was calibrated with a standard chlorophyll solution (45). Major macronutrients (level of detection, 1 μM) were measured as previously described (44). DNA was collected and extracted following a commercial protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), with the exception of adding a 1-min bead beating step at 4,800 rpm with ∼0.25 g of sterile 0.1-mm zirconium beads (Biospec, Bartlesville, OK) at the beginning of the protocol (65).

Quantitative PCR.

Primers for pufM, which encodes the M subunit of the photosynthetic reaction center complex that is unique to BChl-containing bacteria, were pufM-557F (5′-TACGGSAACCTGTWCTAC-3′) and pufM_WAWR (5′-GCRAACCACCANGCCCA-3′) and were used to amplify an ∼240-bp fragment of the pufM gene (55, 60). The reaction mixture consisted of 2.5 μl of DNA, 1× SYBR iTaq supermix (Bio-Rad), and 0.1 μM (each) primers in a 25-μl volume, and the PCR protocol was 95°C for 10 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 56°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s (55). Duplicate analytical replicates for duplicate DNA extracts were performed for all samples, and the initial concentration of template was determined based on qPCR standards. qPCR standards were made from cultures of Erythrobacter longus strain NJ3Y (23) cultivated in rich medium (F/2 medium [16], 0.5 g peptone liter−1, and 0.1 g yeast extract liter−1) at 30 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 on a 12-h–12-h light-dark cycle at 25°C. Cultures were grown until the late log growth phase and were harvested at ∼1 × 109 cells ml−1. Extracted DNA was serially diluted to produce DNA standards equivalent to 10−1 to 107 cells ml−1. The average r2 value for standard curves from all qPCR runs was 0.99, and the amplification efficiency was ∼100%. The mean standard detection limit was 37 pufM copies ml−1. Sterilized water and DNAs from Alteromonas UH00601 (38) and Prochlorococcus MIT9312, both equivalent to 106 cells ml−1, were used as negative controls.

Flow cytometry.

Subsamples for flow cytometry were collected and frozen with 0.125% glutaraldehyde at −80°C (53) for later analysis of prokaryotic phytoplankton (Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus) (22). Samples stained with 1× SYBR green I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 30 min in the dark before processing were used to measure the total bacterioplankton or “bacteria” (36).

Diversity of pufM genes.

Six clone libraries were constructed using the pufM-557F and pufM_WAW primers and the following PCR conditions: 95°C for 10 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 56°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 45 s. Twenty-five-microliter PCR mixtures contained 1× buffer, 15 mM MgCl2, 0.1 μM (each) primers, 6.3 units of Jump Start Taq (Sigma), and 2.5 μl of DNA. For each library, triplicate PCR mixtures were pooled, and bands were gel extracted (Qiagen) and sequenced on an ABI 3730XL capillary sequencer after being ligated to the TOPO-TA vector (Invitrogen) and cloned into Escherichia coli following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Sequences were manually curated using Sequencher (GeneCodes) and aligned in ARB (34), and library sizes ranged from 43 to 47 sequences.

Dissociation curves.

Dissociation curves for pufM amplicons from qPCR were drawn by quantifying the change in amplicon concentration (fluorescence) as the temperature increased from 56 to 95°C at 0.2°C per s. The change in fluorescence with temperature was calculated using the manufacturer's software (Applied Biosystems) and exported for further analysis. Replicate dissociation curves were averaged and normalized to maximum abundance, and major peaks were identified by the locations where the slope of the curve was zero. In addition to dissociation curves for environmental DNA, dissociation curves were also made for 10 clones from each pufM clone library to determine the phylogenetic association of major dissociation curve peaks.

Data handling and analyses.

Means and standard deviations are reported for all replicated data. Environmental variables were considered “high” when they were >1 standard deviation above the mean. Correlations and Spearman rank values were calculated using Minitab. Gene fragment libraries were analyzed with MOTHUR (48) to compare numbers of shared operational taxonomic units (OTUs) among various environments, Shannon diversity indices, and Chao1 estimator values. Phylogenetic associations with environmental variables and location were determined using the UniFrac significance test and by implementing the Bonferroni correction as well as using the environmental clustering option to cluster the environments based on phylogenetic lineages that they contain (33). Each AAP bacterium was assumed to have 1 copy of the pufM gene (49, 64), and % AAP bacteria in the total bacterial community was calculated by dividing the number of AAP bacteria ml−1 (or pufM copies ml−1) by the total number of bacteria ml−1 as enumerated by flow cytometry. Phylogenetic trees were plotted using iTOL v2 (31).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers JQ340498 to JQ340769.

RESULTS

Environmental variability.

With the exception of California, all of the stations along the sampled transects are within 60 km of shore. However, freshwater inputs are minimal for each of these regions, and salinity varies only from 31 to 38. Temperature ranged between 17°C (California) and 28°C (Futuna and Aniwa) but varied little along the nearshore/offshore transects, with the exception of the Kaneohe Bay transects (sampled on 13 June 2006), where temperatures were between 22°C and 27°C. For a majority of transects, the highest salinity and lowest temperatures were observed offshore, but overall these gradients were not strong. All of the stations sampled are oligotrophic, with PO4 and NO2 concentrations below the limit of detection (1 μM). However, nitrate was detectable in 25 of 59 locations and varied from 1 to 3.3 μM NO3, but this was not correlated with distance from shore.

Total chlorophyll a was highest in Kaneohe Bay (some stations had >3 μg Chl a liter−1) but was low (<0.5 μg Chl a liter−1) for other transects, and for all transects, the concentration decreased with distance from shore. Total bacterial concentrations ranged from 1.3 × 105 to 3.2 × 106 cells ml−1 and averaged (9.4 ± 5.3) × 105 cells ml−1. The abundance of Prochlorococcus, which ranged from 2.4 × 103 to 1.2 × 105 cells ml−1, comprised <1 to 28% of the total bacterial community. The abundance of Synechococcus varied from 70 to 6.7 × 105 cells ml−1 and comprised <1 to 22% of the total bacterial community. Synechococcus was most abundant in Kaneohe Bay and least abundant near the oligotrophic waters of Futuna, Aniwa, Oahu, and Molokai. Due to the different horizontal (length) scales of environmental variability for the various transects, the abundances of Prochlorococcus, Synechococcus, and total bacteria were not correlated with the distance from shore or with NO3 concentrations.

AAP bacterial abundance.

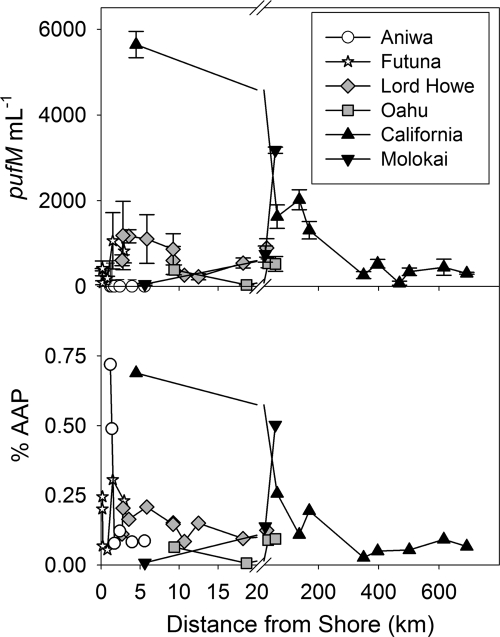

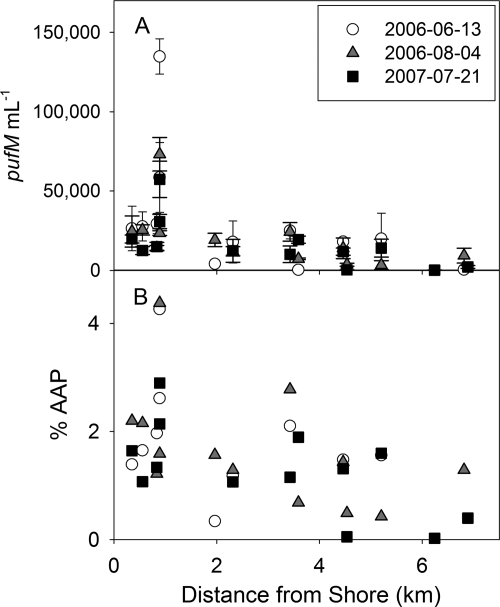

The mean abundance of AAP bacteria in the surface waters sampled was 11,107 cells ml−1, comprising 1.2%, on average, of the total bacterial population, and was maximal near the surface where depth profiles were measured (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Nevertheless, these percentages were highly variable, with 180% and 122% coefficients of variation for the abundance and percentage, respectively (Fig. 2 and 3). These mean values were strongly influenced by the high abundances found in Kaneohe Bay (21,626 ± 24,743 cells ml−1; 1.6% ± 1.0% AAP bacteria) relative to the other locations (837 ± 1,017 cells ml−1; 0.2% ± 0.2% AAP bacteria) (Fig. 3); however, offshore, oligotrophic stations near Kaneohe Bay had AAP bacterial abundances similar to those of other regions. In general, AAP bacterial abundances and percentages were highest nearshore and decreased offshore (Fig. 2 and 3), with the notable exception of Molokai, where abundances and percentages of the total bacteria were highest offshore. Repeated sampling of the Kaneohe Bay transects showed that in spite of differences in the numbers of total bacteria, the AAP bacterial abundances and percentages were remarkably consistent for the 3 days sampled over the 1-year period. In spite of substantial variability among the stations in environmental variables and AAP bacteria, there was no relationship between the abundance of AAP bacteria and the distance from shore or NO3 concentration (Table 1). However, AAP bacteria were strongly correlated with total bacteria, Synechococcus, total chlorophyll, and picoplankton (0 to 2 μm) chlorophyll a. AAP bacteria were also weakly correlated with temperature and Prochlorococcus. Because of the larger dynamic ranges of these environmental variables, these relationships were most predictive for Kaneohe Bay but were still present for the other transects.

Fig 2.

AAP bacterial abundance (top) and % AAP (of total bacteria) (bottom) for Aniwa (circles), Futuna (stars), Lord Howe (diamonds), Oahu (squares), Molokai (downward-facing triangles), and California (upward-facing triangles). Error bars indicate 1 standard deviation. Note the break in axis at 20 kilometers from shore.

Fig 3.

AAP bacterial abundance (A) and % AAP (of total bacteria) (B) in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, HI, sampled 13 June 2006 (circles), 4 August 2006 (triangles), and 21 July 2007 (squares).

Table 1.

Regression coefficients for AAP bacterial abundance and environmental variables for the global data set

| Variable (units) | n | r | P value | Spearman's rank value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synechococcus abundance (cells ml−1) | 94 | 0.87 | <0.01 | 0.832 |

| Total chlorophyll a concn (μg liter−1) | 94 | 0.80 | <0.01 | 0.852 |

| Bacterial abundance (cells ml−1) | 94 | 0.78 | <0.01 | 0.823 |

| Picoplankton (0 to 2 μm) chlorophyll a concn (μg liter−1) | 77 | 0.74 | <0.01 | 0.758 |

| Temp (°C) | 94 | 0.34 | <0.01 | 0.335 |

| Prochlorococcus abundance (cells ml−1) | 94 | 0.22 | <0.01 | −0.589 |

| Distance from shore (km) | 79 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −0.334 |

| Salinity | 72 | −0.10 | 0.40 | 0.424 |

| Nitrate (NO3−) concn (μM) | 25 | 0.03 | 0.96 | 0.238 |

Dissociation curves.

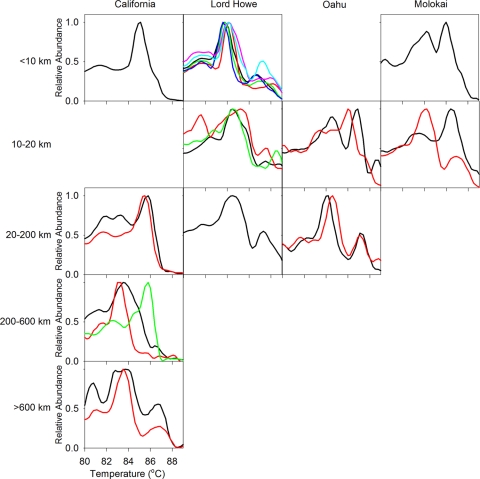

The dissociation curves (melt curves) for pufM amplicons, which can be used as an index of AAP bacterial genetic diversity and community complexity (49), have multiple peaks indicating different AAP bacterial populations (Fig. 4). The most dominant peaks occur between 81°C and 88°C. Some peaks (e.g., ∼84°C) are observed for nearly all stations and transects, whereas other peaks (e.g., 86°C) are more variable. The relative magnitudes of these peaks, which are proportional to the abundances of the populations they represent, change among transects and along transects. Some transects, such as the California transect, have increasing numbers of dissociation curve peaks and associated AAP bacterial community complexity with distance from shore. Other transects, such as the Lord Howe, Oahu, and Molokai transects, have clusters that dominate specific regions along the transect, with no clear trends in the complexity of the community. Nearshore transects with a finer spatial scale generally have similar patterns to those of the larger-scale transects (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), and overall, these dissociation curves suggest a complex AAP bacterial community which may be structured along environmental gradients.

Fig 4.

Dissociation curves as a function of distance from shore for California, Lord Howe, Oahu, and Molokai. Multiple curves in a given plot indicate that multiple stations were sampled within the distance bin.

pufM diversity.

Community complexity was examined further using clone libraries from nearshore and offshore stations from selected transects. Specifically, representative samples from Aniwa (AN1 and AN6), California (CA2 and CA5), and Oahu (OA1 and OA3) were selected because of the geographic distance between sampling sites and because their dissociation curves have unique community profiles among nearshore and offshore stations both within a transect and between transects (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). For Oahu and California, the vast majority (>95%) of sequences identified through BLAST (BLASTn) searches (3) using the NCBI nr/nt database were most similar to uncultured representatives, whereas for Aniwa, 32% of the sequences were most similar to pufM sequences from cultured representative members of the Rhodobacter, Roseobacter, and Erythrobacter genera. Clones were highly diverse, and the distance between major clades ranged from 80% to ∼94% sequence identity (Fig. 5; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Most of the top hits for sequences that were BLAST searched against the refseq_genomic NCBI database were either gammaproteobacterial (95 sequences) or alphaproteobacterial (109 sequences) sequences, and only 5 sequences were most similar to betaproteobacterial sequences. Another 46 sequences, mostly from the California libraries, were not similar to any cultured representative in this database but were similar to other environmental pufM sequences found in the NCBI nr/nt database. Phylogenetic assignments based on similarity to cultured representatives are incongruent with the pufM phylogeny.

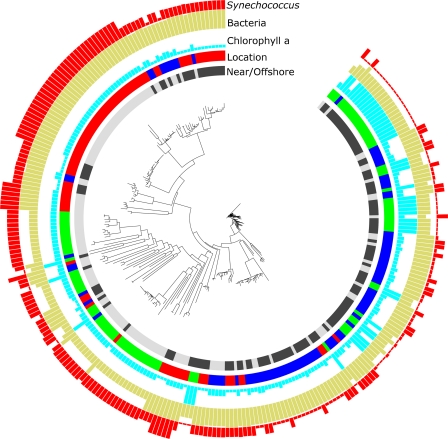

Fig 5.

Phylogenetic relationships (neighbor joining) of pufM gene fragments (240 bp) with associated environmental data. The outside red ring shows relative Synechococcus abundances, the gold ring shows relative total bacterial abundances, the cyan ring shows relative chlorophyll a concentrations, the multicolor location ring indicates the island where each clone was found (blue, Aniwa; green, California; red, Oahu), and the nearshore/offshore ring indicates the proximity of the sample location to shore (light gray, nearshore; dark gray, offshore).

Regardless of the sequence similarity level used for comparison, Aniwa, California, and Oahu have comparable levels of alpha diversity (richness). For example, in comparing unique sequences, there were 227 ± 165, 252 ± 234, and 314 ± 274 OTUs, respectively, determined by the Chao1 richness estimator. However, much of this biodiversity is at the fine genetic scale (i.e., microdiversity), and at the 97% similarity level, Aniwa, California, and Oahu had many fewer OTUs (56 ± 62, 27 ± 22, and 29 ± 31, respectively). Nevertheless, because the rarefaction curves for these clone libraries did not fully saturate (Good's coverage of 82%, 92%, and 90%, respectively, at 97% similarity), the precise number of OTUs remains unconstrained for these locations. Among the island locations, there was only one unique sequence (OTU) shared between California and Oahu. However, at the 97% similarity level, 29% of the OTUs found in California were also found in Oahu. Twenty-nine percent of the OTUs found in Oahu were also found in Aniwa, but only 1 OTU was shared between Aniwa and California. Thus, from the Eastern to Western Pacific, there may be some overlap in the genetic biodiversity of AAP bacteria between “adjacent” locations, but this does not appear to extend to the stations separated by the most distance. Similarly, only 3 sequences were shared between the offshore and nearshore stations of Oahu, 1 between the offshore and nearshore stations of Aniwa, and none between the stations of California, and at 97% similarity, 2 OTUs were shared between the offshore and nearshore stations of Aniwa, 1 between the stations of California, and 6 between the stations of Oahu. Comparing offshore and nearshore stations collectively among islands, 5 of the sequences were shared between all sites (<3% of the total), whereas at the 97% similarity level, 30% of the OTUs found nearshore were also found offshore. The nearshore and offshore environments had significantly different (P ≤ 0.01) phylogenetic distributions of AAP bacteria as well as reduced Shannon diversity at the 97% similarity level offshore (unique level, 4.6 ± 0.2 versus 4.6 ± 0.2; 97% level, 3.4 ± 0.2 versus 2.7 ± 0.2). These patterns were also apparent in OTUs or phylogenies (P ≤ 0.01) for nearshore or offshore samples for an individual island (Fig. 5; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Thus, in comparing the AAP bacterial communities (57) among the nearshore and offshore stations at different locations, it is clear that the communities differ broadly and that there is relatively high beta diversity (endemism) among the locations (Fig. 5).

Community structure and environmental variability.

In addition to significant clustering among nearshore and offshore pufM gene fragments, there were also associations among other environmental variables and pufM phylogeny (Fig. 5). Among the environmental variables measured, Synechococcus, total bacteria, and chlorophyll a were the variables most strongly correlated with AAP bacterial abundances, and these variables were used to explore the relationships with pufM phylogeny. Specific clades of pufM were significantly (P ≤ 0.01) associated with high abundances of Synechococcus, total bacteria, and chlorophyll. However, there was no statistical difference in the number of unique or 97% similar OTUs present for high or normal levels of Synechococcus, total bacteria, and chlorophyll. Yet the Shannon diversity indices for unique and 97% similar OTUs were reduced in areas with high Synechococcus (unique level, 3.1 ± 0.3 versus 5.1 ± 0.1; 97% level, 1.5 ± 0.3 versus 3.3 ± 0.2) or chlorophyll (unique level, 3.5 ± 0.2 versus 5.1 ± 0.1; 97% level, 1.5 ± 0.2 versus 3.5 ± 0.1) concentrations. A high abundance of total bacteria also reduced the Shannon diversity indices of AAP bacteria, but less dramatically (unique level, 4.0 ± 0.2 versus 4.9 ± 0.1; 97% level, 2.6 ± 0.2 versus 3.1 ± 0.2).

Dissociation curves for selected clone library sequences.

Dissociation curves were measured for selected pufM clones to identify the major clades that contributed to the original dissociation curve temperature peaks (Fig. 4) and to verify that the patterns observed for the dissociation curves are representative of the genetic diversity of pufM in the community. Most clusters had distinct temperature ranges that represented one of the major peaks found in the dissociation curve from the original community (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). However, some clades had multiple temperature peaks or a range of temperature peaks, and a few clades had dissociation curve peaks that were not represented in the original dissociation curve. For example, gene fragment libraries from the nearshore station from California (CA2) had four phylogenetic clusters, and dissociation curves for these clusters had temperature peaks from 84 to 86°C (see Fig. S4). This is consistent with the major broad peak at ∼85.5°C in the original dissociation curve. However, two nearshore peaks (82 and 83°C) from the original dissociation curve were not present for the pufM clones sampled. The offshore station from California (CA5) had one phylogenetic cluster with temperatures representing the major dissociation peak at ∼83°C for the community curve. Other peaks, found at ∼86°C and associated with sequences from offshore California sequences, were also consistent with the sequence-based community profile. Dissociation curves generated from clones from major clades found in Aniwa and Oahu were similarly consistent with the whole-community dissociation curve profiles generated from these locations. Comparisons between the islands indicate that the dissociation curve temperature peaks cannot be assigned to a specific taxonomic group or clade but are indicative of unique groups of pufM sequences and, therefore, AAP bacterial populations.

DISCUSSION

AAP bacterial abundance was generally greatest nearshore, particularly in Kaneohe Bay, Oahu, HI. Among the sites sampled, Kaneohe Bay is unique, with two river inputs (southern and central bay) which do not significantly affect the local salinity but do substantially affect the turbidity (10). AAP bacteria have been reported to be influenced by river inputs due to increased particle loads, decreased light attenuation, potential freshwater reservoirs of AAP bacteria, and changes in salinity (55). For example, in the Delaware and Chesapeake Estuaries, the highest AAP bacterial abundance was associated with turbidity maxima and AAP bacterial abundance was correlated with light attenuation and particles (55). However, in addition to levels of turbidity, other aspects of habitat type are also important: grouping island habitats into lagoons protected by barrier reefs (Kaneohe Bay, Lord Howe, and Aniwa) and comparing those to islands with steep cliffs and fringing reefs (Futuna and Molokai) confirmed that the abundance of AAP bacteria decreases with distance from shore for islands with barrier reefs, in contrast to islands with steep cliffs, which have no distinct patterns (or the highest abundance furthest from shore). Similarly, distributions of AAP bacteria near Kaneohe Bay's river inputs may be associated with benthic habitats that influence the residence time of coastal waters or resuspension of particles. The abundance of AAP bacteria and their contribution to the total bacterioplankton reported here are consistent with results reported by others for a wide variety of environments (49). Our numbers are from a pufM qPCR-based approach; thus, any inefficiencies in DNA extraction or limitations of the oligonucleotide primers in capturing the suite of diversity of AAP bacteria could lead to an underestimation of the true abundance. Therefore, our numbers should be viewed as lower estimates of the actual contribution of AAP bacteria to the total microbial community.

While there were some relationships between AAP bacteria and physical variables or distance to shore, the strongest correlations were observed for the biological variables measured, including chlorophyll, Synechococcus, and total bacteria (Table 1). Associations with chlorophyll have been well documented since the initial discovery of AAP bacteria in the open ocean (15, 27); however, the mechanism underlying this association is still not known. Since AAP bacteria are mixotrophic, this tight coupling could be driven by their dependence on dissolved organic matter (DOM) derived from leaky or lysed phytoplankton cells (59). Although AAP bacterial abundance was also strongly correlated with total bacterial abundance (Table 1) and the broader bacterioplankton community increased with phytoplankton abundance, the percent contribution of AAP bacteria to the total bacterioplankton community also increased near shore (Fig. 2), suggesting that this stimulation disproportionately favors AAP bacteria.

DOM derived from phytoplankton is complex, and biological communities that utilize freshly produced DOM vary depending on the constituents of the DOM pool produced (17, 47, 52). Different taxa of phytoplankton can alter bacterioplankton community composition due to the production of preferred DOM (42). For this study, Kaneohe Bay was the most eutrophic site sampled, and its phytoplankton community is dominated by Synechococcus (10); AAP bacteria were most abundant at that location. For the other locations, phytoplankton communities were dominated by Prochlorococcus and AAP bacteria were less abundant, suggesting that AAP bacteria may be stimulated specifically by DOM produced by Synechococcus. Alternatively, AAP bacteria may have a similar (or overlapping) ecological niche to that of Synechococcus. Globally, Synechococcus bacteria are most abundant near coastal upwelling regions and other dynamic mesotrophic environments (51, 66, 67). Similar patterns have been described for AAP bacteria, suggesting that similar mechanisms may control these two bacterial groups (49). Genomic analyses revealed that some clades of Synechococcus are capable of using phototrophic and heterotrophic metabolisms (41), further suggesting that they may utilize similar resources to those of AAP bacteria. These two hypotheses are not mutually exclusive.

In addition to varying in abundance, the AAP bacterial population was genetically diverse as characterized by both gene fragment libraries and qPCR dissociation curves, and this diversity was structured geographically and along environmental gradients (Fig. 4 and 5). For example, the presence/absence and magnitude of specific peaks of dissociation curves changed along with distance from shore along environmental gradients both within an island transect and between island locations (Fig. 4). Also, pufM fragment libraries from select locations showed that specific clades of AAP bacteria were associated with specific environmental conditions. Together, these results demonstrate that the changes observed for abundance also had associated changes in AAP bacterial population genetic diversity. Similar to previous studies of other oceanographic regions, most of the AAP bacteria sampled here belonged to the alpha- and gammaproteobacterial subclasses (37, 60, 62), although ∼20% could not be assigned definitively. In addition, because it is likely that the photosynthetic genes can be transferred laterally (39), we cannot exclude the possibility of some misassignments of AAP bacteria to subclasses, although these were likely rare in the context of this ecological study. Among the assigned subclasses, there is substantial genetic variability in both coastal and open ocean environments (6, 19, 40, 62). Like the case for other marine bacteria, much of this genetic diversity is found at the microscale (2), as only 27 (California) to 56 (Aniwa) OTUs are predicted at the 97% level, whereas there are >200 OTUs predicted at the 100% identity level for all of the locations. However, even at 97% similarity, there is biogeographic partitioning among populations, with Oahu sharing OTUs with both Aniwa and California but with no substantial overlap for the more distant Aniwa and California sites. Similarly, open ocean AAP bacterial communities are distinct from those from nearshore sites, both within an island transect and between islands. These results are consistent with phylogeographic partitioning of OTUs and general island biogeography theory (35). Yet this genetic diversity of AAP bacteria is structured along environmental gradients (Fig. 5), and similar to the case with other model bacteria, specific clades of AAP bacteria are associated with environmental variables (20, 21). In particular, some clades of AAP bacteria that are associated with high (or low) levels of bacterioplankton, chlorophyll, or Synechococcus may be regulated by associations with DOM or other related environmental variables. Together, these results demonstrate that environmental variables regulate both the abundance and diversity of AAP bacteria but that endemism may also be a contributing factor in structuring the genetic diversity of these communities. Exhaustive sampling of the AAP bacterial community diversity at geographically discrete locations would distinguish between the relative contributions of these distinct but important processes in regulating the abundance and diversity of AAP bacterial communities in marine environments.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by funds from the U.S. National Science Foundation (OCE05-26462, OCE05-50798, and OCE10-31064).

We acknowledge Susan Brown and Mathew Church for critical readings of prior versions of this work, Jerome Aucan for Kaneohe Bay bathymetry data, and Kevin Bartlett for help with quantitative analysis. We also acknowledge helpful comments from the anonymous reviewers.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 February 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Achenbach LA, Carey J, Madigan MT. 2001. Photosynthetic and phylogenetic primers for detection of anoxygenic phototrophs in natural environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2922–2926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Acinas SG, et al. 2004. Fine-scale phylogenetic architecture of a complex bacterial community. Nature 430:551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altschul SF, et al. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beja O, et al. 2002. Unsuspected diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Nature 415:630–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bryant DA, Frigaard N-U. 2006. Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated. Trends Microbiol. 14:488–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cho JC, et al. 2007. Polyphyletic photosynthetic reaction centre genes in oligotrophic marine gammaproteobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1456–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cottrell MT, Kirchman DL. 2009. Photoheterotrophic microbes in the Arctic Ocean in summer and winter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4958–4966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cottrell MT, Mannino A, Kirchman DL. 2006. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the Mid-Atlantic Bight and the North Pacific Gyre. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:557–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cottrell MT, Ras J, Kirchman DL. 2010. Bacteriochlorophyll and community structure of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in a particle-rich estuary. ISME J. 4:945–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox EF, et al. 2006. Temporal and spatial scaling of planktonic responses to nutrient inputs into a subtropical embayment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 324:19–35 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Csotonyi JT, Swiderski J, Stackebrandt E, Yurkov V. 2010. A new environment for aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria: biological soil crusts. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 675:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Denner EBM, et al. 2002. Erythrobacter citreus sp. nov., a yellow-pigmented bacterium that lacks bacteriochlorophyll a, isolated from the western Mediterranean Sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:1655–1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fuchs BM, et al. 2007. Characterization of a marine gammaproteobacterium capable of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:2891–2896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gich F, Overmann J. 2006. Sandarakinorhabdus limnophila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel bacteriochlorophyll a-containing, obligately aerobic bacterium isolated from freshwater lakes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56:847–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goericke R. 2002. Bacteriochlorophyll a in the ocean: is anoxygenic bacterial photosynthesis important? Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:290–295 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guillard RRL, Ryther JH. 1962. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 8:229–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hold GL, et al. 2001. Characterisation of bacterial communities associated with toxic and non-toxic dinoflagellates: Alexandrium spp. and Scrippsiella trochoidea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 37:161–173 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holm-Hansen O, Riemann B. 1978. Chlorophyll a determination: improvements in methodology. Oikos 30:438–447 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu Y, Du H, Jiao N, Zeng Y. 2006. Abundant presence of the γ-like proteobacterial pufM gene in oxic seawater. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 263:200–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hunt DE, et al. 2008. Resource partitioning and sympatric differentiation among closely related bacterioplankton. Science 320:1081–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jiao N, et al. 2007. Distinct distribution pattern of abundance and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the global ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 9:3091–3099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson ZI, et al. 2010. The effects of iron- and light-limitation on phytoplankton communities of deep chlorophyll maxima of the Western Pacific Ocean. J. Mar. Res. 68:1–26 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koblizek M, et al. 2003. Isolation and characterization of Erythrobacter sp strains from the upper ocean. Arch. Microbiol. 180:327–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koblizek M, Masin M, Ras J, Poulton AJ, Prasil O. 2007. Rapid growth rates of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in the ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2401–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kolber Z. 2007. Energy cycle in the ocean: powering the microbial world. Oceanography 20:79–88 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolber ZS, et al. 2001. Contribution of aerobic photoheterotrophic bacteria to the carbon cycle in the ocean. Science 292:2492–2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kolber ZS, Van Dover CL, Niederman RA, Falkowski PG. 2000. Bacterial photosynthesis in surface waters of the open ocean. Nature 407:177–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Labrenz M, Lawson PA, Tindal BJ, Collins MD, Hirsch P. 2005. Roseisalinus antarcticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel aerobic bacteriochlorophyll a-producing alpha-proteobacterium isolated from hypersaline Ekho Lake, Antarctica. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55:41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lami R, et al. 2007. High abundances of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria in the South Pacific Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:4198–4205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lami R, Cuperova Z, Ras J, Lebaron P, Koblãzek M. 2009. Distribution of free-living and particle-attached aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in marine environments. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 55:31–38 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Letunic I, Bork P. 2011. Interactive Tree Of Life v2: online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:W475–W478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li Q, Jiao N, Peng Z. 2006. Environmental control of growth and BChl a expression in an aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacterium, Erythrobacter longus (DSMZ6997). Acta Oceanol. Sin. 25:138–144 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lozupone C, Knight R. 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8228–8235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ludwig W, et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363–1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. MacArthur RH, Wilson EO, Whittaker RH. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marie D, Partensky F, Jacquet S, Vaulot D. 1997. Enumeration and cell cycle analysis of natural populations of marine picoplankton by flow cytometry using the nucleic acid stain SYBR green I. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:186–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Masín M, et al. 2006. Seasonal changes and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in the Baltic Sea. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 45:247–254 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morris JJ, Kirkegaard R, Szul MJ, Johnson ZI, Zinser ER. 2008. Facilitation of robust growth of Prochlorococcus colonies and dilute liquid cultures by “helper” heterotrophic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4530–4534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nagashima K, Hiraishi A, Shimada K, Matsuura K. 1997. Horizontal transfer of genes coding for the photosynthetic reaction centers of purple bacteria. J. Mol. Evol. 45:131–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oz A, Sabehi G, Koblizek M, Massana R, Beja O. 2005. Roseobacter-like bacteria in Red and Mediterranean Sea aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:344–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Palenik B, et al. 2006. Genome sequence of Synechococcus CC9311: insights into adaptation to a coastal environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:13555–13559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pinhassi J, et al. 2004. Changes in bacterioplankton composition under different phytoplankton regimens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6753–6766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rathgeber C, Beatty JT, Yurkov V. 2004. Aerobic phototrophic bacteria: new evidence for the diversity, ecological importance and applied potential of this previously overlooked group. Photosynth. Res. 81:113–128 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ringuet S, Sassano L, Johnson ZI. 2011. A suite of microplate reader-based colorimetric methods to quantify ammonium, nitrate, orthophosphate and silicate concentrations for aquatic nutrient monitoring. J. Environ. Monit. 13:370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ritchie R. 2006. Consistent sets of spectrophotometric chlorophyll equations for acetone, methanol and ethanol solvents. Photosynth. Res. 89:27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Salka I, et al. 2008. Abundance, depth distribution, and composition of aerobic bacteriochlorophyll a-producing bacteria in four basins of the central Baltic Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:4398–4404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schäfer H, Abbas B, Witte H, Muyzer G. 2002. Genetic diversity of ‘satellite’ bacteria present in cultures of marine diatoms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 42:25–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schloss PD, et al. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7537–7541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schwalbach MS, Fuhrman JA. 2005. Wide-ranging abundances of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the world ocean revealed by epifluorescence microscopy and quantitative PCR. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50:620–628 [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sieracki ME, Gilg IC, Thier EC, Poulton NJ, Goericke R. 2006. Distribution of planktonic aerobic anoxygenic photoheterotrophic bacteria in the northwest Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51:38–46 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tai V, Palenik B. 2009. Temporal variation of Synechococcus clades at a coastal Pacific Ocean monitoring site. ISME J. 3:903–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Teira E, et al. 2008. Linkages between bacterioplankton community composition, heterotrophic carbon cycling and environmental conditions in a highly dynamic coastal ecosystem. Environ. Microbiol. 10:906–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vaulot D, Courties C, Partensky F. 1989. A simple method to preserve oceanic phytoplankton for flow cytometric analyses. Cytometry 10:629–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Waidner LA, Kirchman DL. 2005. Aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis genes and operons in uncultured bacteria in the Delaware River. Environ. Microbiol. 7:1896–1908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Waidner LA, Kirchman DL. 2007. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria attached to particles in turbid waters of the Delaware and Chesapeake estuaries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3936–3944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Welschmeyer NA. 1994. Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll a in the presence of chlorophyll b and pheopigments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39:1985–1992 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yue JC, Clayton MK. 2005. A similarity measure based on species proportions. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 34:2123–2131 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yurkov V, Beatty JT. 1998. Isolation of aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria from black smoker plume waters of the Juan de Fuca Ridge in the Pacific Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:337–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yurkov VV, Beatty JT. 1998. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:695–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yutin N, Beja O. 2005. Putative novel photosynthetic reaction centre organizations in marine aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria: insights from metagenomics and environmental genomics. Environ. Microbiol. 7:2027–2033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yutin N, et al. 2009. BchY-based degenerate primers target all types of anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria in a single PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7556–7559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yutin N, et al. 2007. Assessing diversity and biogeography of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in surface waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans using the Global Ocean Sampling expedition metagenomes. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1464–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang Y, Jiao N. 2007. Dynamics of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the East China Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 61:459–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zheng Q, et al. 2011. Diverse arrangement of photosynthetic gene clusters in aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. PLoS One 6:e25050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zinser ER, et al. 2006. Prochlorococcus ecotype abundances in the North Atlantic Ocean revealed by an improved quantitative PCR method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:723–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zwirglmaier K, et al. 2007. Basin-scale distribution patterns of picocyanobacterial lineages in the Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1278–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zwirglmaier K, et al. 2008. Global phylogeography of marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus reveals a distinct partitioning of lineages among oceanic biomes. Environ. Microbiol. 10:147–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.