Abstract

Rationale and Objectives

Relapse to old unhealthy eating habits while dieting is often provoked by stress or acute exposure to palatable foods. We adapted a rat reinstatement model, which is used to study drug relapse, to study mechanisms of relapse to palatable food seeking induced by food-pellet priming (non-contingent exposure to a small amount of food pellets) or injections of yohimbine (an alpha-2 adrenoceptor antagonist that causes stress-like responses in humans and non-humans). Here, we assessed the predictive validity of the food reinstatement model by studying the effects of fenfluramine, a serotonin releaser with known anorectic effects, on reinstatement of food seeking.

Methods

We trained food-restricted female and male rats to lever-press for 45-mg food pellets (3-h sessions) and first assessed the effect of fenfluramine (0.75, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg, i.p.) on food-reinforced responding. Subsequently, we extinguished the food-reinforced responding and tested the effect of fenfluramine (1.5, and 3.0 mg/kg) on reinstatement of food seeking induced by yohimbine injections (2 mg/kg, i.p.) or pellet priming (4 non-contingent pellets).

Results

Fenfluramine decreased yohimbine- and pellet priming-induced reinstatement. As expected, fenfluramine also decreased food-reinforced responding, but a control condition in which we assessed fenfluramine’s effect on high-rate operant responding indicated that the drug’s effect on reinstatement was not due to performance deficits.

Conclusions

The present data support the predictive validity of the food reinstatement model and suggest that this model could be used to identify medications for prevention of relapse induced by stress or acute exposure to palatable food during dietary treatments.

Keywords: Animal models, Fenfluramine, Diet, Food self-administration, Predictive validity, Reinstatement, Relapse, Stress

Many people attempt to control their food consumption by dieting but they typically relapse to their old unhealthy eating habits within a few months (Kramer et al. 1989; Peterson and Mitchell 1999; Skender et al. 1996). There is evidence that this relapse is often triggered by exposure to palatable foods, exposure to food-associated cues, or exposure to stress (Byrne et al. 2003; Gorin et al. 2004; Grilo et al. 1989; Herman and Polivy 1975; Kayman et al. 1990; McGuire et al. 1999; Polivy and Herman 1999; Torres and Nowson 2007).

Despite the established pattern of relapse to unhealthy eating habits during dieting in humans, the mechanisms of this phenomenon have rarely been studied in animal models (Nair et al. 2009b). To address this issue, we and others adapted a rat reinstatement model, commonly used to study relapse to abused drugs (See 2002; Self and Nestler 1998; Shaham et al. 2003), to investigate mechanisms of relapse to food seeking (Nair et al. 2009a). In this model, relapse in food-restricted (dieting) rats can be triggered by acute exposure to small amounts of food (herein referred to as ‘pellet priming’) or food-associated cues (De Vries et al. 2005; Ghitza et al. 2007), or systemic injections of the pharmacological stressor yohimbine (Ghitza et al. 2006; Nair et al. 2011; Richards et al. 2008). Yohimbine is an alpha-2 adrenoceptor antagonist that induces stress- and anxiety-like states in both humans and laboratory animals (Bremner et al. 1996a; b; Holmberg and Gershon 1961; Lang and Gershon 1963).

A key feature of the food reinstatement model is that the rats are maintained on mild food restriction conditions that are commonly used in many drug self-administration studies (Belin et al. 2009; Picciotto and Corrigall 2002) and studies on the neurobiological mechanisms of appetitive learning and motivation (Balleine and Dickinson 1998; Kelley and Berridge 2002). The chronic diet condition was chosen because human studies suggest that dietary restraint leads to increased vulnerability to stress- and food-cue-induced food craving and relapse to palatable food intake (Herman and Polivy 1975; Polivy et al. 2005; Polivy and Herman 1999).

Over the last decade, the widespread use of the reinstatement model has led to a debate about the validity of this procedure as an animal model of drug relapse in humans (Epstein et al. 2006; Fuchs et al. 1998; Katz and Higgins 2003). The recent use of the reinstatement model to study relapse to food seeking has also raised the question whether findings from studies using this model relate to mechanisms of relapse to unhealthy eating habits during dieting (Nair et al. 2009a).

We sought to test the predictive validity of the reinstatement model by examining the effect of fenfluramine on reinstatement of food seeking in food-restricted (a dieting condition) rats. In the psychiatry literature, predictive validity typically refers to the ability of an animal model to identify drugs with potential therapeutic value (Geyer and Markou 1995; Markou et al. 1993; Sarter and Bruno 2002; Willner 1984). The serotonin releaser fenfluramine is a highly effective anorectic agent in both laboratory animals and humans (Davis and Faulds 1996; McGuirk et al. 1991; Rowland and Charlton 1985) that was removed from clinical use due to adverse health effects (Rothman and Baumann 2002). While in previous food reinstatement studies we only used male rats (Ghitza et al. 2006; Ghitza et al. 2007; Nair et al. 2009b; Nair et al. 2011), here we studied female rats in addition to male rats, because the proportion of women who use dietary supplements and seek dietary treatment is more than twice that of men (Davy et al. 2006; Pillitteri et al. 2008). Finally, we assessed the effect of fenfluramine on ongoing food-reinforced responding for food pellets under two training conditions—operant training sessions every day or every-other-day—that lead to moderate or high response rates, respectively. The assessment of the first training condition (every day) was performed in order to compare the effect of fenfluramine on food-reinforced responding to its effect on reinstatement of food seeking. The assessment of the second training condition (every other day) was performed in order to rule out the possibility that fenfluramine’s inhibitory effect on reinstatement of food seeking is due to performance deficits.

Materials and methods

Subjects and apparatus

Long-Evans female (n=24; NIDA breeding program; 200–340 g) and male (n=24; Charles River, 300–350 g) were maintained on a reverse 12-h:12-h light:dark cycle (lights off at 8:00 am). Two female rats were excluded from the study due to poor health or unreliable food-reinforced responding during training. The rats were weighed daily. The female and male rats were food-restricted to 9–11 or 15–17 g/day, respectively, of standard rat chow (about 55–65% of their daily food intake) during the training phase, and to 12–14 g/day or 18–22 g, respectively, to maintain relatively stable body weight during the extinction and reinstatement test phases. The daily rat chow ration was given after the daily sessions. Experiments were conducted in standard self-administration chambers (Med Associates, Georgia, VT). Each chamber had two levers 9 cm above the floor, but only one lever (the “active,” retractable lever) activated the pellet dispenser, which delivered 45-mg food pellets containing 12.7% fat, 66.7% carbohydrate and 20.6% protein (Catalogue # 1811155, TestDiet, Richmond, IN). This pellet type was chosen based on pellet preference tests in food-restricted female rats, using 6 pellet types (obtained from TestDiet and Bioserv) with different compositions of fat (0 to 35%) and carbohydrate (45% to 91% [sugar pellets]) and different flavors (no flavor, banana, chocolate, grape), in which it was determined to be the most preferred pellet. All procedures followed guidelines outlined in the “Principles of laboratory animal care” (NIH publication no. 85–23). Efforts were made to minimize the number of rats used and their suffering.

Drugs

Yohimbine hydrochloride, purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), was dissolved in sterile water and injected in a volume of 0.5 ml/kg, i.p. The yohimbine dose is based on previous studies in male rats (Ghitza et al. 2007; Nair et al. 2009b; Nair et al. 2008) and a pilot study with female rats. (±)-Fenfluramine HCl (formula weight = 267.7), obtained from the NIDA IRP Pharmacy, was dissolved in distilled water (male rats every-day training dose-response testing) or sterile saline (all other test conditions) and injected in a volume of 1 ml/kg, i.p. Fenfluramine doses are based on previous studies on the drug’s effect on food intake (Burton et al. 1981; Rivera and Eckel 2005) and reinstatement of cocaine seeking (Burmeister et al. 2003).

Procedures

Both male and female rats were run in 2 groups (morning, afternoon) of n=11–12 rats that were repeatedly tested. The experimental procedure included 4 phases: 1) initial training for food-reinforced responding, 2) determination of fenfluramine’s effect on ongoing food-reinforced responding (morning groups), or continuation of training (afternoon groups), 3) extinction of the food-reinforced responding, and 4) repeated tests for fenfluramine’s effect on yohimbine- and pellet priming-induced reinstatement under extinction conditions. Following the test phase, in the morning groups, we also assessed fenfluramine’s effect on ongoing food-reinforced responding during sessions performed every-other-day (see below). During all phases, the sessions started 30 min after rats were placed in the self-administration chambers; 8:30 am for the morning groups and 12:30 pm for the afternoon groups.

Initial training for operant food-reinforced responding

We gave all rats 3-h daily sessions of “autoshaping” for 3 days during which pellets were administered non-contingently every 5 min into a receptacle located near the retracted active lever. Pellet delivery was accompanied by a compound 5-sec tone (2900 Hz) plus light (7.5-W white light cue located above the active lever). Subsequently, we trained the rats to self-administer the pellets on a fixed-ratio-1, 20-sec timeout reinforcement schedule for 5 daily 3-h training sessions. At the start of each session, the red houselight was turned on and the active lever was extended. Reinforced active lever presses resulted in the delivery of one pellet, accompanied by the compound 5-sec tone-light cue. Active lever presses during the 20-sec timeout or presses on the inactive lever had no programmed consequences. Rats were housed in the animal facility and transferred to the self-administration chambers prior to the training sessions, and returned to the facility at the end of the 3-h sessions.

Extinction of food-reinforced responding

The rats were given 13 daily 3-h extinction sessions. During the extinction phase, responses on the previously active lever led to tone-light cue presentations, but not pellet delivery.

Effect of fenfluramine on ongoing operant food-reinforced responding

Every-day training

After rats achieved stable levels of lever pressing for food pellets (training day 5), we used a within-subjects design to determine the effect of fenfluramine (0, 0.75, 1.5 and 3 mg/kg, i.p.; counterbalanced order) on ongoing food-reinforced responding. We injected the morning rats (n=11–12 per group) with vehicle or fenfluramine 30 min before the 3-h daily sessions. Half of the female rats were tested on days 6–9 of training and the other half on days 10–13; when not tested, the female rats were given a regular training session). The male rats were injected with fenfluramine every 48 h with regular training sessions given in the intervening days. Concurrently, the afternoon rats (n=11–12 per group) underwent daily training sessions so that the total number of training sessions (with or without fenfluramine) was equal in both groups prior to the extinction phase.

Every-other-day retraining

Using the same experimental design described above, we studied the effects of fenfluramine (0, 1.5 and 3 mg/kg, i.p.; counterbalanced) on ongoing food-reinforced responding after retraining the rats to lever-press for food pellets on an every-other-day schedule. We have added this experimental condition (which leads to high rate of responding, see Fig. 2) at the end of the reinstatement tests in order to rule out the possibility that fenfluramine’s effects on reinstatement of food seeking are due to performance deficits. Following the reinstatement tests, we retrained 10 female and 12 male rats from the morning group to lever-press for food pellets in 3 training sessions conducted every-other-day, over 6 days. We then injected vehicle or fenfluramine every-other-day, 30 min before the 3-h sessions. The female and male rats received 9 g or 16 g of regular food per day, respectively, in their home cages during the retraining days and the fenfluramine test days.

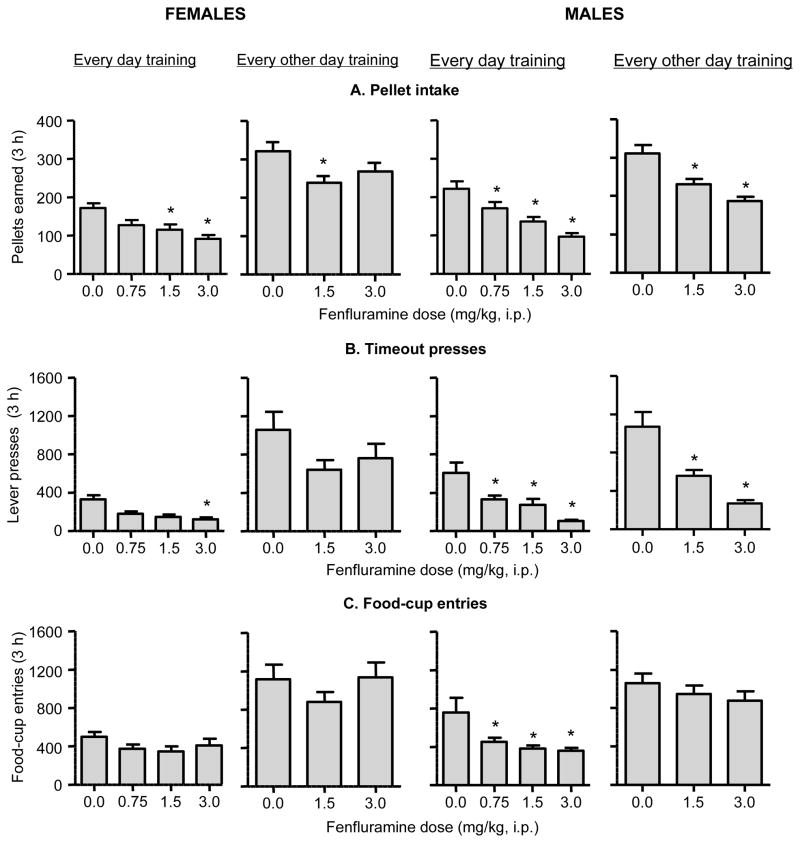

Fig. 2. Effect of fenfluramine on food-reinforced responding in female and male rats.

Mean±sem number of (A) pellets earned, (B) timeout (T.O.) responses on the active lever (total active lever presses minus pellets earned), and (C) foodcup entries after fenfluramine injections under every-day training (n=12 females, n=12 males) or every-other-day retraining (n=10 females, n=12 males) conditions. Fenfluramine or vehicle was injected 30 min before the start of the test sessions. Different from the saline condition, * p<0.05.

Effect of fenfluramine on yohimbine- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement

We used a within-subjects design with the factors of Fenfluramine Dose (0, 1.5, and 3 mg/kg; counterbalanced order), and Yohimbine Dose (0 and 2 mg/kg, counterbalanced order) or Pellet Priming (0 and 4 pellets, counterbalanced order) to study the effects of fenfluramine on yohimbine- and pellet priming-induced reinstatement of food seeking. During the tests for yohimbine-induced reinstatement, the rats received injections of saline (vehicle) or fenfluramine that were immediately followed by injections of water (vehicle) or yohimbine (2 mg/kg) 30 min before the start of the test sessions. During the tests for pellet-priming-induced reinstatement, the rats received injections of saline (vehicle) or fenfluramine 30 min before the start of the test sessions and received 0 (no pellet) or 4 non-contingent pellets within 1 min after the start of the sessions. The rats were tested for both the effect of fenfluramine or its vehicle on yohimbine- or pellet-priming-induced reinstatement, and for the effect of fenfluramine or its vehicle on baseline extinction responding (the yohimbine vehicle condition or the no pellet condition). The test sessions were performed every 48 h with regular extinction sessions in the intervening days in which the rats were not injected with fenfluramine or yohimbine, or exposed to pellet priming.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using mixed-factor ANCOVAs in Statistica. The dependent measures for ongoing food-reinforced responding were the number of pellets earned, timeout responding (lever-presses during the 20-sec timeout after each pellet delivery), and food-cup entries (a common measure of food seeking in learning and memory studies (Balleine and Dickinson 1991; Holland 2008)). The dependent measures during the extinction and reinstatement tests were the number of presses on the previously active lever and food-cup entries. In the statistical analyses of the reinstatement data, the baseline (0 pellets or yohimbine vehicle) extinction responding after fenfluramine vehicle (saline) injections is based on a mean of 3 sessions performed during early, middle, and late testing, and baseline extinction responding after injections of 1.5 or 3.0 mg/kg fenfluramine is based on two interspaced sessions during testing. Because yohimbine increased inactive lever presses (Table 1), a potential measure of non-specific behavioral activation/suppression and/or response generalization (Shalev et al. 2002), we used this measure as a covariate in all analyses. Thus, the ANCOVAs for assessing food-reinforced responding included the between-subjects factor of Sex (female, male), the within-subjects factor of Fenfluramine Dose (0, 0.75, 1.5, 3.0 mg/kg or 0, 1.5, 3.0 mg/kg), and the covariate of inactive lever presses. The ANCOVAs for assessing reinstatement of food seeking included the between-subjects factor of Sex, the within-subjects factors of Fenfluramine Dose and Yohimbine Dose (0, 2 mg/kg) or Pellet Priming (0, 4 pellets), and the covariate of inactive lever presses. One male and two female rats were excluded from the analysis of fenfluramine’s effect on yohimbine-induced reinstatement, because the number of presses on the inactive lever was more than three standard deviations higher than the group’s mean. The factors used in the statistical analyses are described in the Results section below. Significant interaction effects (p<0.05) in the different ANOVAs were followed by post-hoc Tukey tests.

Table 1.

Summary of inactive lever presses during the reinstatement testing

| Measure | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|

| Pellet reinstatement | ||

| Vehicle | 1.7±0.5 | 3.4±1.3 |

| 1.5 mg/kg fenfluramine | 0.5±0.3* | 3.2±1.0 |

| 3.0 mg/kg fenfluramine | 0.4±0.2* | 2.3±1.1 |

| Yohimbine reinstatement | ||

| Vehicle | 11.1±2.5 | 27.8±7.8 |

| 1.5 mg/kg fenfluramine | 3.8±1.0* | 12.5±4.4* |

| 3.0 mg/kg fenfluramine | 1.7±0.8* | 9.3±3.7* |

Data are mean±SEM.

represents significant difference from the vehicle condition, ANOVA and Tukey test, p<0.05.

Results

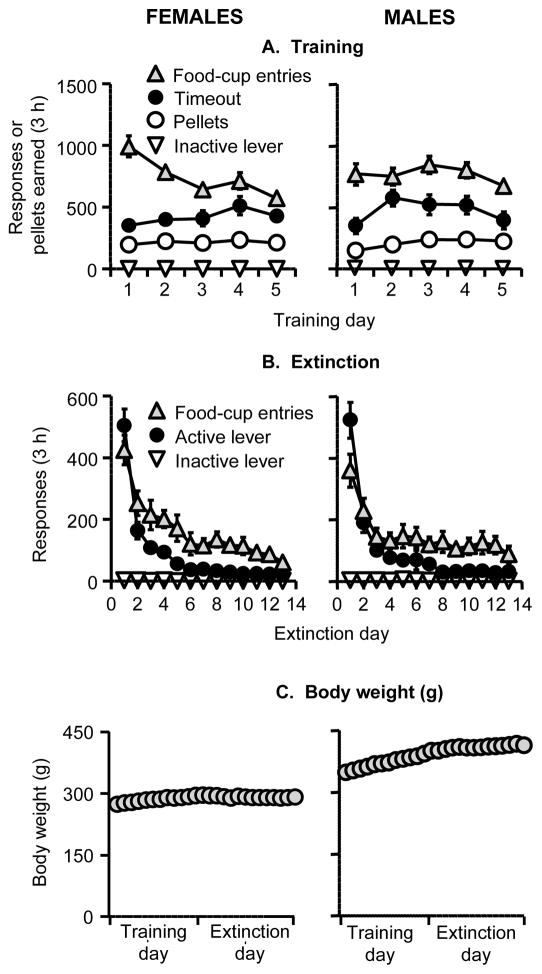

The rats were initially trained to lever press for food pellets for 5 days (3-h/day) and demonstrated reliable food-reinforced responding, but the time course of responding over days somewhat differed between the females versus the males (Fig 1A). The statistical analysis showed an interaction of Sex x Training Day for pellets and time-out responses (F4,172=7.5 and F4,172=2.5, respectively, p values <0.05) but no main effect of Sex (p values>0.1). There was no main effect or interaction of Sex on food-cup entries (p values>0.1). During the extinction phase, active-lever pressing and food-cup entries decreased over days with a similar time course for the females and the males (Fig. 1B). The statistical analysis showed a main effect of Extinction Session (p<0.01), but no effect of Sex or Sex x Extinction Session interaction for active lever presses or food-cup entries (p values>0.1). During the training and extinction phases, the body weight of the female rats remained stable while the body weight of the males increased during training and remained relatively stable during the extinction phase (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Initial training for food-reinforced responding, extinction of food-reinforced responding, and body weights during training and extinction in female and male rats.

(A) Initiation of food-reinforced responding: Mean±sem number of food pellets earned, timeout (T.O.) responses on the active lever (total lever-presses minus pellets earned), foodcup entries, and inactive lever presses during the training sessions. Rats were trained on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR-1) 20-sec timeout reinforcement schedule (n=22 females and 24 males). (B) Extinction of food-reinforced responding: Mean±sem number of responses on the previously active lever. (C) Body weight: Mean±sem body weights during the training and extinction phases. During the training phase, the females and male rats were maintained on 9–11 or 15–17 g/day, respectively, of regular chow food and were given 3-h access to food pellets every day. During the extinction pellets, food pellets were not available in the self administration chambers and the female and male rats were maintained on 12–14 g/day or 18–22 g/day, respectively, of regular chow to maintain stable body weight.

Effect of fenfluramine on ongoing operant food-reinforced responding

Every day training

Fenfluramine injections decreased pellet intake and timeout active-lever presses in both female and male rats, but decreased food-cup entries only in male rats (Fig. 2). The statistical analyses for pellet intake and timeout active lever presses showed significant effects of Fenfluramine Dose (F3,63=28.7 and F3,63=17.0, respectively, p<0.01) and Sex (F1,21=4.3 and F1,21=7.3, respectively, p<0.05), but no interaction (p>0.1). The statistical analyses for food-cup entries showed a significant effect of Fenfluramine Dose (F3,63=8.6, p<0.01) and a significant Fenfluramine Dose x Sex interaction (F3,63=3.1, p<0.05), but no effect of Sex (p>0.1). Fenfluramine had no effect on inactive lever responding, which was very low in all conditions (data not shown).

Every-other-day training

The rats were retrained after the reinstatement tests to lever-press for food pellets every-other-day. Under these conditions, which led to substantially higher response rates than in the every-day training condition, fenfluramine injections also decreased pellet intake and timeout active-lever presses (effect of Fenfluramine Dose: F2,38=25.1 and F2,38=18.6, p<0.01, respectively) (Fig. 2). There was no significant main effect of Sex or interaction of Sex x Fenfluramine Dose for either measure (all p>0.05), but as can be seen in Fig. 2, the effect of the high fenfluramine dose (3 mg/kg) on pellet intake and timeout responding and the low fenfluramine dose for timeout responding was significant for males but not females. The female rats made more food-cup entries than male rats (effect of Sex: F1,19=7.4, p<0.05), but there was no effect of Fenfluramine Dose or Sex x Fenfluramine dose (all p>0.05). Fenfluramine had no effect on inactive lever responding, which was low in all conditions (data not shown).

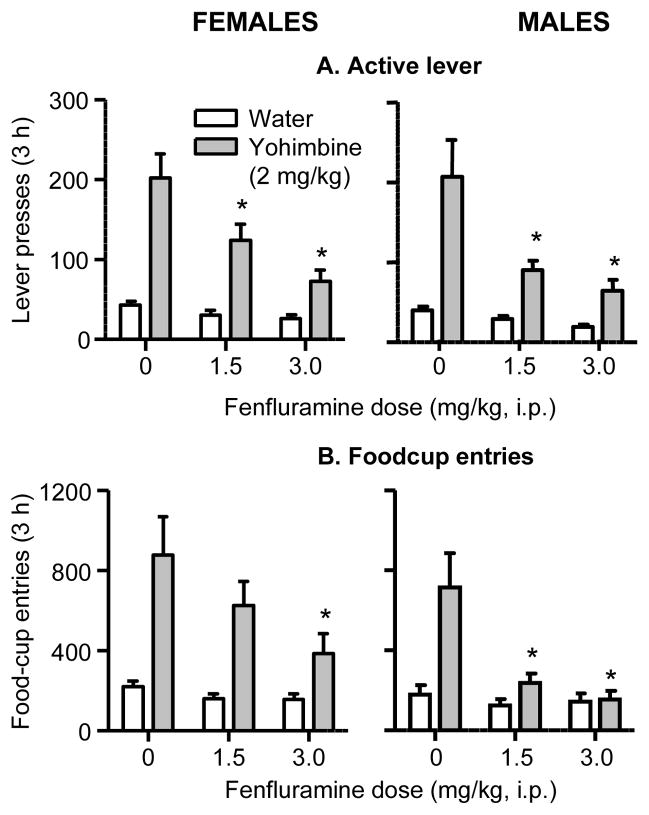

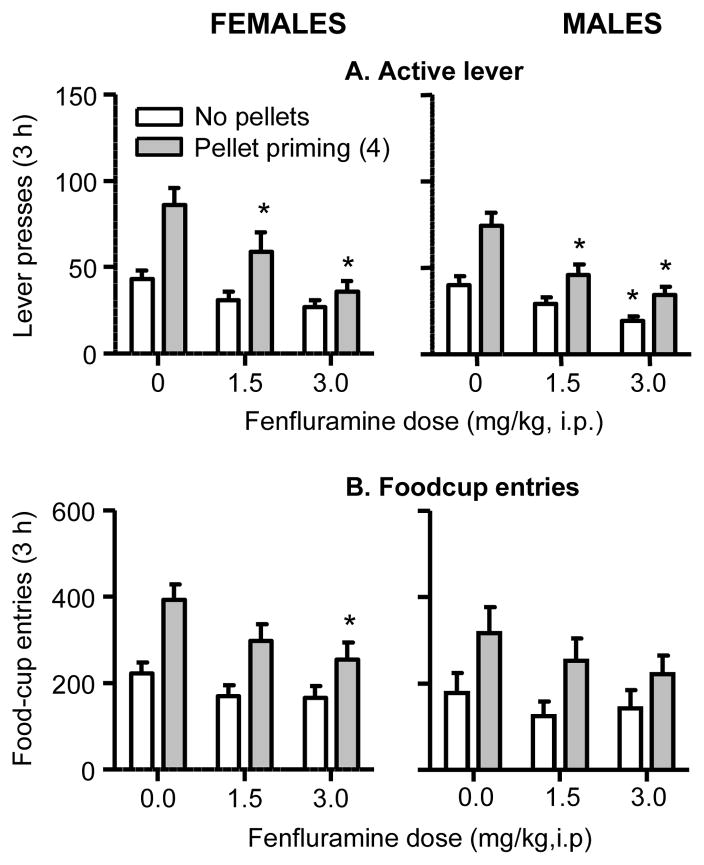

Effect of fenfluramine on yohimbine- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement

Fenfluramine attenuated yohimbine- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement of active lever presses in both males and females (Fig. 3–4). Fenfluramine also attenuated yohimbine-induced reinstatement of food-cup entries in both males and females (Fig. 3), but had a weaker effect on pellet-priming-induced reinstatement of food-cup entries in both sexes (Fig. 4). In both females and males, the higher dose of fenfluramine also somewhat decreased baseline active lever extinction responding, but not food-cup entries (Fig. 3–4). In the analyses below, an interaction between Fenfluramine Dose and Yohimbine Dose or Pellet Priming reflects a selective or preferential effect of fenfluramine on the dependent measure (active lever or food-cup entries) during the reinstatement condition (2 mg/kg yohimbine or 4 pellets) versus the baseline extinction condition (water injection or 0 pellets). Finally, with an exception of some effect of time of day on yohimbine-induced reinstatement in female rats (lower responding in the afternoon group), lever-presses and foodcup entries did not significantly differ between the rats tested in the morning versus the afternoon (data not shown); additionally, we did not observe habituation to the experimental manipulations over repeated testing (data not shown).

Fig. 3. Effect of fenfluramine on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of food seeking in female and male rats.

Mean±sem number of (A) active lever presses and (B) foodcup entries in rats injected with saline (vehicle) or fenfluramine that were immediately followed by injections of water (vehicle) or yohimbine (2 mg/kg) 30 min before the start of the test sessions (n=20 females, n=23 males). Different from the saline condition, * p<0.05.

Fig. 4. Effect of fenfluramine on pellet-priming-induced reinstatement of food seeking in female and male rats.

Mean±sem number of (A) active lever presses and (B) foodcup entries in rats injected with saline (vehicle) or fenfluramine 30 min before the start of the test sessions; in the pellet priming condition the rats received 4 non-contingent pellets within 1 min after the start of the sessions (n=22 females, n=24 males). Different from the saline condition, * p<0.05.

Yohimbine—lever presses

The analysis showed significant effects of Yohimbine Dose (F1,40=26.3, p<0.01), Fenfluramine Dose (F2,80=11.6, p<0.01), and Fenfluramine Dose x Yohimbine Dose (F2,80=5.4, p<0.01). There was no main effect or interaction with Sex.

Yohimbine—foodcup entries

The analysis showed significant effects of Sex (F1,40=4.4, p<0.05), Yohimbine Dose (F1,40=20.3, p<0.01), Fenfluramine Dose (F2,80=8.7, p<0.01) and Fenfluramine Dose x Yohimbine Dose (F2,80=7.0, p<0.01). The significant effect of Sex reflects overall higher foodcup entries in females than in males across the three fenfluramine dose conditions.

Pellet priming—lever presses

The analysis showed significant effects of Pellet Priming (F1,43=56.7, p<0.01), Fenfluramine Dose (F2,86=28.5, p<0.01) and Fenfluramine Dose x Pellet Priming (F2,86=9.1, p<0.01). There was no main effect or interaction with Sex.

Pellet priming—foodcup entries

The analysis showed significant effects of Pellet Priming (F1,43=71.8, p<0.01) and Fenfluramine Dose (F2,86=7.0, p<0.01); no other effects or interactions were significant.

Discussion

We assessed the predictive validity of the food reinstatement model by determining the effect of fenfluramine, a serotonin releaser with known anorectic effects (Rowland and Charlton 1985), on reinstatement of food seeking induced by the pharmacological stressor yohimbine or non-contingent pellet priming. In both males and females, fenfluramine decreased yohimbine-induced reinstatement of active lever presses, the traditional measure of reward seeking in reinstatement studies (Stewart and de Wit 1987). Fenfluramine also decreased yohimbine-induced reinstatement of foodcup entries (a secondary measure of oral reward seeking in reinstatement studies (Burattini et al. 2006; Le et al. 2011) and appetitive learning and motivation studies (Balleine and Dickinson 1991; Holland 2008; Kelley and Berridge 2002), but had a more modest effect on pellet-priming-induced foodcup entries. These data support the predictive validity of the food reinstatement procedure.

A main finding in our study is the overall lack of sex differences for either yohimbine- or pellet-priming-induced reinstatement or fenfluramine’s effect on reinstatement of food seeking. The results for yohimbine-induced reinstatement are different from those demonstrating stronger yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (Anker and Carroll 2010) or yohimbine-induced potentiation of cue-induced cocaine seeking (Feltenstein et al. 2011b) in female rats than in male rats. However, our findings are consistent with the report of lack of sex differences in yohimbine-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking (Feltenstein et al. 2011a). Feltenstein et al. (2011b) also reported a role of ovarian hormones/estrous cycle in yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Here, we did not assess the ovarian hormones’ role in reinstatement of food seeking, but it is unlikely that fluctuations in hormone levels confound data interpretation. We recently found that ovariectomy had a very modest effect on pellet-priming-induced reinstatement and no effect on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of food seeking. Additionally, both yohimbine- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement were not influenced by the estrous cycle phase (Cifani et al. 2011).

There is evidence for sex differences in extinction responding (Kerstetter et al. 2008) and drug-priming-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking (Carroll et al. 2004; Lynch 2006). In contrast, we did not observe sex differences in either extinction responding or pellet-priming-induced reinstatement of food seeking. Thus, the type of the self-administered reward and the type of the reinstatement manipulation can determine whether sex and/or ovarian hormones will influence reinstatement of reward seeking.

The finding that fenfluramine decreased yohimbine-induced reinstatement of food seeking is in agreement with previous reports on the effect of fenfluramine or the SSRI fluoxetine on footshock-stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking (Le et al. 2006; Le et al. 1999). These present and previous results suggest that increasing brain serotonin levels decreases reward seeking. This notion is supported by the finding that fenfluramine or fluoxetine decrease cue-induced cocaine seeking (Baker et al. 2001; Burmeister et al. 2003). Conversely, local inhibition of median raphe serotonergic neurons reinstates alcohol seeking (Le et al. 2002) and serotonin depletion increases cue-induced sucrose seeking (Tran-Nguyen et al. 2001).

In agreement with previous reports (Foltin and Fischman 1988; Taylor 1973; Willner et al. 1990), fenfluramine decreased food-maintained responding. In females, but not males, this effect was more reliable in the every-day training condition (which led to moderate response rates) than in the every-other-day training condition (which led to higher response rates). Unexpectedly, fenfluramine only minimally affected foodcup entries in both training conditions in females and the every-other-day condition in males. The reasons for fenfluramine’s dissociable effects on lever-presses versus foodcup entries during training for females (but not males), which was not observed during reinstatement testing, are unknown.

Methodological considerations

There are two main methodological issues that should be considered before concluding that fenfluramine’s effect on reinstatement of food seeking reflects a decrease in the motivation to seek food. The first is that fenfluramine’s effect is due to non-specific behavioral suppression; the second is that our repeated testing procedure confounds data interpretation. We discuss these issues below.

Non-specific behavioral suppression

The findings that the higher dose of fenfluramine (3 mg/kg) decreased baseline lever-pressing extinction responding (Fig. 4) and pellet-prime- (in females) and yohimbine-induced increases (in both sexes) in inactive lever-presses (Table 1) suggest that fenfluramine’s effect on reinstatement and ongoing food-reinforced responding might be due to non-specific behavioral suppression. However, two lines of evidence indicate that this alternative interpretation is unlikely. First, in the assessment of food-reinforced responding, mean±sem total number of active lever responses (pellets earned + timeout responses per 3 h) after injections of the high fenfluramine dose (3 mg/kg) was either similar (every-day testing: females, 211±28; males, 201±20) or substantially higher (every-other-day testing: females, 1027±153; males, 457±37) than the response rates during testing in the vehicle condition during the reinstatement tests (about 100 and 200 active lever presses for pellet priming and yohimbine, respectively (Fig. 3–4). This difference suggests that fenfluramine’s effect on reinstatement is not the result of lever-pressing impairments during testing after pretreatment with the drug. Additionally, as can be seen in Fig. 2, the rats were capable of performing hundreds of foodcup entries in the every-day food-reinforced testing and eight-hundred (in males) to over a thousand (in females) foodcup entries in the every-other-day testing after injections of the high fenfluramine dose (Fig. 2). Again, these findings suggest that decreased lever responding and foodcup entries during the reinstatement tests are not due to fenfluramine-induced motor deficits.

Yohimbine modestly increased inactive lever presses (Table 1), a potential measure of non-directed activity and/or response generalization (Shalev et al. 2002), and this effect was attenuated by fenfluramine. It is unlikely that yohimbine’s effect on inactive lever presses confound our data interpretation, because both yohimbine’s effect on active lever presses and fenfluramine’s effect on yohimbine-induced reinstatement remained significant when inactive lever was used as a covariate (see Results). Additionally, there is no clear evidence that yohimbine increases general activity or operant responding. For example, previous studies showed that yohimbine either increased (Schroeder et al. 2003) or decreased (Chopin et al. 1986) locomotion, and either increased (Sethy and Winter 1972), did not change (Hughes et al. 1996), or decreased (Munzar and Goldberg 1999) food-maintained operant responding. Finally, yohimbine’s effect on inactive lever presses appeared stronger in males than in females (Table 1). Whether this effect is reliable/reproducible is unknown, because in our previous studies with male rats (Ghitza et al. 2006; Ghitza et al. 2007; Nair et al. 2009b; Nair et al. 2008; Nair et al. 2011), yohimbine’s effect on inactive lever-presses was much smaller than the effect we observed here. More generally, while inactive lever data are commonly used in self-administration and reinstatement studies, interpretation of such data is not straightforward (see (Shalev et al. 2002)), and there is little evidence that responding on this lever is associated with activity levels in the self-administration chambers (Fowler et al. 2007).

Impact of repeated testing

Under our experimental procedure, the rats were tested repeatedly for both yohimbine- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement under different doses of fenfluramine. A potential concern with this repeated measures experimental design is an order effect. However, for three reasons, it is unlikely that an order effect or development of tolerance to fenfluramine confound data interpretation. First, fenfluramine’s inhibitory effect on reinstatement was similar in the AM groups (previously exposed to fenfluramine during initial training) and the previously fenfluramine-naïve PM groups (data not shown). Second, lever presses or foodcup entries were similar during early and late testing (data not shown). Third, in a repeated measures counterbalanced experimental design, an order effect will increase the variability across the experimental conditions (or increase the error variance), resulting in decreased power for detecting a given experimental effect, but will not introduce a systematic bias within a given experimental condition. Finally, we and others have used repeated testing in pharmacological studies on reinstatement of drug seeking and obtained reliable results (De Vries et al. 2002; de Wit and Stewart 1981; Fuchs et al. 2005; Self et al. 1996; Shaham et al. 1998; Spealman et al. 1999; Weiss et al. 2001).

The reinstatement procedure and predictive validity

The reinstatement procedure is widely used to study neurobiological mechanisms of drug relapse and to identify medications for relapse prevention (over 500 published papers since 2005). More recently, we and others have begun using this procedure to identify mechanisms underlying relapse to palatable food seeking during dieting (Nair et al. 2009a). Yet, the predictive validity of the reinstatement procedure in its true sense—medications first identified in the animal model that later demonstrated clinical efficacy for relapse prevention—has not been established (Epstein et al. 2006; Katz and Higgins 2003). Our data showing that fenfluramine attenuates yohimbine- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement of food seeking supports the “postdictive” validity of the food reinstatement procedure. Postdictive validity refers to a situation in which an effective medication in humans was subsequently demonstrated to be effective in the animal model (Goldstein and Simpson 2002; Nunnally and Bernstein 1994).

Our results are in agreement with data from several studies in which approved medications for drug addiction were subsequently assessed in the reinstatement procedure. For example, relapse to alcohol use is modestly decreased by naltrexone (O’Malley et al. 1992; Volpicelli et al. 1992) or acamprosate (Sass et al. 1996; Whitworth et al. 1996). In rats, these drugs decrease alcohol-priming- and cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking (Bachteler et al. 2005; Burattini et al. 2006; Ciccocioppo et al. 2003; Le et al. 1999; Liu and Weiss 2002), but see Heidbreder et al. (2007) for negative results for cue-induced reinstatement in mice. Additionally, buprenorphine and methadone maintenance are effective treatments for preventing relapse to heroin use in humans (Dole et al. 1966; Jasinski et al. 1978). In rats, chronic delivery of these drugs after self-administration training decreases heroin-priming-induced reinstatement (Leri et al. 2004; Sorge et al. 2005). Furthermore, varenicline is a recently FDA-approved effective medication for the treatment of nicotine addiction (Gonzales et al. 2006; Oncken et al. 2006). In rats, systemic injections of the drug decrease nicotine-priming- and nicotine-priming+discrete-cue-induced reinstatement (O’Connor et al. 2010); varenicline, however, does not affect discrete-cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking (O’Connor et al. 2010; Wouda et al. 2011).

On the other hand, there are examples of effective medications for relapse prevention in humans, like bupropion (Hurt et al. 1997), which reinstates rather than inhibits drug (nicotine) seeking in rats following acute injections (Liu et al. 2008). There are also examples of drugs that decrease reinstatement of drug (cocaine) seeking, like fluoxetine (Burmeister et al. 2003), that do not demonstrate clinical efficacy (Grabowski et al. 1995). Thus, like other animal models of psychiatric disorders (Geyer and Markou 1995; Sarter and Bruno 2002; Willner 1984), the concordance between the effects of drugs in the reinstatement procedure and the human condition is not perfect.

Finally, an issue to consider in our study and other animal reinstatement studies is that, with a few exceptions (Amen et al. 2011; Reichel et al. 2011), drugs are typically tested for their acute effect on reinstatement, while in humans drugs are given chronically (see Epstein et al. (2006) for a discussion of this issue and its implications for accounting for some differences between results from reinstatement studies and human clinical trials). Thus, a question for future research is whether fenfluramine would also decrease reinstatement of food seeking when administered chronically during the extinction and reinstatement phases. However, similarity in the drug treatment conditions between the animal model and the human condition, while preferable, is not a requirement for the animal model’s predictive (or postdictive) validity (Sarter and Bruno 2002). For example, in the forced-swim test, an animal model with established predictive validity for depression, drugs are tested for their acute or short-term (e.g., 2 injections in 24 h) effects on behavior (Porsolt 2000; Porsolt et al. 1978; Wong et al. 2000).

Concluding remarks

We found that fenfluramine, an effective pharmacological treatment for excessive food intake in humans, decreased reinstatement of food seeking induced by the pharmacological stressor yohimbine and acute exposure to the palatable food in both female and male rats. These data support the predictive validity of the food reinstatement procedure. We hope that our findings will encourage feeding and addiction researchers to use this procedure to identify novel medications for prevention of relapse during dietary treatments.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. CLP, CC, and BMN equally contributed to this paper.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Amen SL, Piacentine LB, Ahmad ME, Li SJ, Mantsch JR, Risinger RC, Baker DA. Repeated N-acetyl cysteine reduces cocaine seeking in rodents and craving in cocaine-dependent humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:871–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker JJ, Carroll ME. Sex differences in the effects of allopregnanolone on yohimbine-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;107:264–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachteler D, Economidou D, Danysz W, Ciccocioppo R, Spanagel R. The effects of acamprosate and neramexane on cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior in rat. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1104–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Tran-Nguyen TL, Fuchs RA, Neisewander JL. Influence of individual differences and chronic fluoxetine treatment on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:18–26. doi: 10.1007/s002130000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine B, Dickinson A. Instrumental performance following reinforcer devaluation depends on incentive learning. Q J Exp Psychol B. 1991;43:279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Dickinson A. Goal-directed instrumental action: contingency and incentive learning and their cortical substrates. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:407–419. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Jonkman S, Dickinson A, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Parallel and interactive learning processes within the basal ganglia: Relevance for the understanding of addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:89–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety: I. preclinical studies. Synapse. 1996a;23:28–38. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<28::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Charney DS. Noradrenergic mechanisms in stress and anxiety: II.clinical studies. Synapse. 1996b;23:39–51. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199605)23:1<39::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burattini C, Gill TM, Aicardi G, Janak PH. The ethanol self-administration context as a reinstatement cue: acute effects of naltrexone. Neuroscience. 2006;139:877–87. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister JJ, Lungren EM, Neisewander JL. Effects of fluoxetine and d-fenfluramine on cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:146–54. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MJ, Cooper SJ, Popplewell DA. The effect of fenfluramine on the microstructure of feeding and drinking in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1981;72:621–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb09142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne S, Cooper Z, Fairburn C. Weight maintenance and relapse in obesity: a qualitative study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:955–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Morgan AD, Cosgrove KP. Sex and estrogen influence drug abuse. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:273–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopin P, Pellow S, File SE. The effects of yohimbine on exploratory and locomotor behaviour are attributable to its effects at noradrenaline and not at benzodiazepine receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25:53–7. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccocioppo R, Lin D, Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F. Reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior by drug cues following single versus multiple ethanol intoxication in the rat: effects of naltrexone. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:208–215. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifani C, Navarre BM, Calu DJ, Baumann MH, Marchant N, Liu Q-R, Koya E, Shaham Y, Hope BT. Stress- and pellet-priming-induced reinstatement of food seeking and neuronal activation in c-fos-GFP transgenic female rats: Role of ovarian hormones. Soc Neurosci. 2011:Abstr 37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5895-11.2012. Program no. 728.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R, Faulds D. Dexfenfluramine. An updated review of its therapeutic use in the management of obesity. Drugs. 1996;52:696–724. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy SR, Benes BA, Driskell JA. Sex differences in dieting trends, eating habits, and nutrition beliefs of a group of midwestern college students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1673–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, de Vries W, Janssen MC, Schoffelmeer AN. Suppression of conditioned nicotine and sucrose seeking by the cannabinoid-1 receptor antagonist SR141716A. Behav Brain Res. 2005;161:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer ANM, Binnekade R, Raasø H, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Relapse to cocaine- and heroin-seeking behavior mediated by dopamine D2 receptors is time-dependent and associated with behavioral sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:18–26. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Stewart J. Reinstatement of cocaine-reinforced responding in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 1981;75:134–143. doi: 10.1007/BF00432175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole VP, Nyswander ME, Kreek MJ. Narcotic blockade. Arch Intern Med. 1966;118:304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y. Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0529-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Ghee SM, See RE. Nicotine self-administration and reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in male and female rats. Drug Alcohol Depend (online) 2011a doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Henderson AR, See RE. Enhancement of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking in rats by yohimbine: sex differences and the role of the estrous cycle. Psychopharmacology. 2011b;216:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2187-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Food intake in baboons: effects of d-amphetamine and fenfluramine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1988;31:585–92. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler SC, Covington HE, 3rd, Miczek KA. Stereotyped and complex motor routines expressed during cocaine self-administration: results from a 24-h binge of unlimited cocaine access in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:465–78. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Ledford CC, Parker MP, Case JM, Mehta RH, See RE. The role of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and dorsal hippocampus in contextual reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:296–309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Specio SE, Groff RS, Neisewander JL. Predictive validity of the extinction/reinstatement model of drug craving. Psychopharamacology. 1998;135:151–160. doi: 10.1007/s002130050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Markou A. Animal models of psychiatric disorders. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ, editors. Psychopharmacology: the fourth generation of progress. Raven Press; New York: 1995. pp. 787–798. [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Gray SM, Epstein DH, Rice KC, Shaham Y. The anxiogenic drug yohimbine reinstates palatable food seeking in a rat relapse model: a role of CRF(1) receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2188–2196. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghitza UE, Nair SG, Golden SA, Gray SM, Uejima JL, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. Peptide YY3-36 decreases reinstatement of high-fat food seeking during dieting in a rat relapse model. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11522–11532. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5405-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Simpson JC. Validity: Definition and Applications to Psychiatric Research. In: Tsuang MT, Tohen M, editors. Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2. Wiley-Liss; New York: 2002. pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin AA, Phelan S, Wing RR, Hill JO. Promoting long-term weight control: does dieting consistency matter? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:278–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski J, Rhoades H, Elk R, Schmitz J, Davis C, Creson D, Kirby K. Fluoxetine is ineffective for treatment of cocaine dependence or concurrent opiate and cocaine dependence: two placebo-controlled double-blind trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15:163–174. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199506000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Shiffman S, Wing RR. Relapse crises and coping among dieters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:488–495. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Andreoli M, Marcon C, Hutcheson DM, Gardner EL, Ashby CR., Jr Evidence for the role of dopamine D3 receptors in oral operant alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior in mice. Addiction Biol. 2007;12:35–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CP, Polivy J. Anxiety, restraint, and eating behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84:66–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Cognitive versus stimulus-response theories of learning. Learn Behav. 2008;36:227–41. doi: 10.3758/lb.36.3.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg G, Gershon S. Autonomic and psychic effects of yohimbine hydrochloride. Psychopharmacologia. 1961;2:93–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00592678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CE, Habash T, Dykstra LA, Picker MJ. Discriminative-stimulus effects of morphine in combination with alpha- and beta-noradrenergic agonists and antagonists in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;53:979–86. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, Khayrallah MA, Schroeder DR, Glover PN, Sullivan CR, Croghan IT, Sullivan PM. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. New Eng J Med. 1997;337:1195–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski DR, Pevnick JS, Griffith JD. Human pharmacology and abuse potential of the analgesic buprenorphine: a potential agent for treating narcotic addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:501–16. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770280111012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Higgins ST. The validity of the reinstatement model of craving and relapse to drug use. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayman S, Bruvold W, Stern JS. Maintenance and relapse after weight loss in women: behavioral aspects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:800–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.5.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AE, Berridge KC. The neuroscience of natural rewards: relevance to addictive drugs. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3306–3311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter KA, Aguilar VR, Parrish AB, Kippin TE. Protracted time-dependent increases in cocaine-seeking behavior during cocaine withdrawal in female relative to male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;198:63–75. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer FM, Jeffery RW, Forster JL, Snell MK. Long-term follow-up of behavioral treatment for obesity: patterns of weight regain among men and women. Int J Obes. 1989;13:123–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang WJ, Gershon S. Effects of psychoactive drugs on yohimbine induced responses in conscious dogs. A proposed screening procedure for anti-anxiety agents. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1963;142:457–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Funk D, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Fletcher PJ, Shaham Y. Effects of dexfenfluramine and 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;186:82–92. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0346-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Funk D, Juzytsch W, Coen K, Navarre BM, Cifani C, Shaham Y. Effect of prazosin and guanfacine on stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol and food seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (online) 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Fletcher PJ, Shaham Y. The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the median raphe nucleus in relapse to alcohol. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7844–7849. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07844.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Poulos CX, Harding S, Watchus W, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Effects of naltrexone and fluoxetine on alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol seeking induced by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:435–444. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Tremblay A, Sorge RE, Stewart J. Methadone maintenance reduces heroin- and cocaine-induced relapse without affecting stress-induced relapse in a rodent model of poly-drug use. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1312–1320. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Palmatier MI, Donny EC, Sved AF. Cue-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats: effect of bupropion, persistence over repeated tests, and its dependence on training dose. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:365–75. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0967-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Weiss F. Additive effect of stress and drug cues on reinstatement of ethanol seeking: exacerbation by history of dependence and role of concurrent activation of corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7856–7861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ. Sex differences in vulnerability to drug self-administration. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:34–41. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markou A, Weiss F, Gold LH, Caine B, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Animal models of drug craving. Psychopharmacology. 1993;112:163–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02244907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Lang W, Hill JO. What predicts weight regain in a group of successful weight losers? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:177–85. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirk J, Goodall E, Silverstone T, Willner P. Differential effects of d-fenfluramine, l-fenfluramine and d-amphetamine on the microstructure of human eating behaviour. Behav Pharmacol. 1991;2:113–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzar P, Goldberg SR. Noradrenergic modulation of the discriminative-stimulus effects of methamphetamine in rats. Psychopharmacology. 1999;143:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s002130050950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SG, Adams-Deutsch T, Epstein DH, Shaham Y. The neuropharmacology of relapse to food seeking: methodology, main findings, and comparison with relapse to drug seeking. Prog Neurobiol. 2009a;89:18–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SG, Adams-Deutsch T, Pickens CL, Smith DG, Shaham Y. Effects of the MCH1 receptor antagonist SNAP 94847 on high-fat food-reinforced operant responding and reinstatement of food seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009b;205:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SG, Golden SA, Shaham Y. Differential effects of the hypocretin 1 receptor antagonist SB 334867 on high-fat food self-administration and reinstatement of food seeking in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:406–416. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SG, Navarre BM, Cifani C, Pickens CL, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. Role of dorsal medial prefrontal cortex dopamine D1-family receptors in relapse to high-fat food seeking induced by the anxiogenic drug yohimbine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:497–510. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric Theory. 3. McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor EC, Parker D, Rollema H, Mead AN. The alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine-receptor partial agonist varenicline inhibits both nicotine self-administration following repeated dosing and reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:365–76. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1739-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Schottenfeld RS, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B. Naltrexone and coping skills therapy for alcohol dependence. A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:881–887. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oncken C, Gonzales D, Nides M, Rennard S, Watsky E, Billing CB, Anziano R, Reeves K. Efficacy and safety of the novel selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, varenicline, for smoking cessation. Arch Int Med. 2006;166:1571–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Mitchell JE. Psychosocial and pharmacological treatment of eating disorders: a review of research findings. J Clin Psychol. 1999;55:685–697. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199906)55:6<685::aid-jclp3>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Corrigall WA. Neuronal systems underlying behaviors related to nicotine addiction: neural circuits and molecular genetics. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3338–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03338.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri JL, Shiffman S, Rohay JM, Harkins AM, Burton SL, Wadden TA. Use of dietary supplements for weight loss in the United States: results of a national survey. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:790–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Coleman J, Herman CP. The effect of deprivation on food cravings and eating behavior in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38:301–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivy J, Herman CP. Distress and eating: why do dieters overeat? Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26:153–164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199909)26:2<153::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD. Animal models of depression: utility for transgenic research. Rev Neurosci. 2000;11:53–8. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2000.11.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Anton G, Blavet N, Jalfre M. Behavioural despair in rats: a new model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978;47:379–91. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Moussawi K, Do PH, Kalivas PW, See RE. Chronic N-acetylcysteine during abstinence or extinction after cocaine self-administration produces enduring reductions in drug seeking. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;337:487–93. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JK, Simms JA, Steensland P, Taha SA, Borgland SL, Bonci A, Bartlett SE. Inhibition of orexin-1/hypocretin-1 receptors inhibits yohimbine-induced reinstatement of ethanol and sucrose seeking in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1136-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera HM, Eckel LA. The anorectic effect of fenfluramine is increased by estradiol treatment in ovariectomized rats. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:331–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Therapeutic and adverse actions of serotonin transporter substrates. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;95:73–88. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland NE, Charlton J. Neurobiology of an anorectic drug: fenflurmaine. Prog Neurobiol. 1985;27:13–62. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(86)90011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Bruno JP. Animal models in biological psychiatry. In: D’haenen H, den Boer JA, Willner P, editors. Biolotical psychiatry. Johns Willey & Sons Ltd; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sass H, Soyka M, Mann K, Zieglgansberger W. Relapse prevention by acamprosate. Results from a placebo-controlled study on alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:673–680. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830080023006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BE, Schiltz CA, Kelley AE. Neural activation profile elicited by cues associated with the anxiogenic drug yohimbine differs from that observed for reward-paired cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:14–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See RE. Neural substrates of conditioned-cued relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Barnhart WJ, Lehman DA, Nestler EJ. Opposite modulation of cocaine-seeking behavior by D1- and D2-like dopamine receptor agonists. Science. 1996;271:1586–1589. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Nestler EJ. Relapse to drug-seeking: neural and molecular mechanisms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:49–69. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethy VH, Winter JC. Effects of yohimbine and mescaline on punished behavior in the rat. Psychopharmacologia. 1972;23:160–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00401190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Erb S, Leung S, Buczek Y, Stewart J. CP-154,526, a selective, non peptide antagonist of the corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 receptor attenuates stress-induced relapse to drug seeking in cocaine-and heroin-trained rats. Psychopharmacology. 1998;137:184–190. doi: 10.1007/s002130050608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, De Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:3–20. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: a review. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:1–42. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skender ML, Goodrick GK, Del Junco DJ, Reeves RS, Darnell L, Gotto AM, Foreyt JP. Comparison of 2-year weight loss trends in behavioral treatments of obesity: diet, exercise, and combination interventions. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:342–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00096-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorge RE, Rajabi H, Stewart J. Rats maintained chronically on buprenorphine show reduced heroin and cocaine seeking in tests of extinction and drug-induced reinstatement. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1681–1692. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Barrett-Larimore RL, Rowlett JK, Platt DM, Khroyan TV. Pharmacological and environmental determinants of relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:327–336. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, de Wit H. Reinstatement of drug-taking behavior as a method of assessing incentive motivational properties of drugs. In: Bozarth MA, editor. Methods of assessing the reinforcing properties of abused drugs. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1987. pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. The effects of fenfluramine on fixed ratio responding. Psychopharmacologia. 1973;32:351–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00429471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23:887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran-Nguyen TL, Bellew JG, Grote KA, Neisewander JL. Serotonin depletion attenuates cocaine seeking but enhances sucrose seeking and the effects of cocaine priming on reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharamacology. 2001;157:340–348. doi: 10.1007/s002130100822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, O’Brien CP. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876–880. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820110040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Martin-Fardon R, Ciccocioppo R, Kerr TM, Smith DL, Ben Shahar O. Enduring resistance to extinction of cocaine-seeking behavior induced by drug-related cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:361–372. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00238-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth AB, Fischer F, Lesch OM, Nimmerrichter A, Oberbauer H, Platz T, Potgieter A, Walter H, Fleischhacker WW. Comparison of acamprosate and placebo in long-term treatment of alcohol dependence. Lancet. 1996;347:1438–42. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. The validity of animal models of depression. Psychopharmacology. 1984;83:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00427414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, McGuirk J, Phillips G, Muscat R. Behavioural analysis of the anorectic effects of fluoxetine and fenfluramine. Psychopharmacology. 1990;102:273–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02245933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EH, Sonders MS, Amara SG, Tinholt PM, Piercey MF, Hoffmann WP, Hyslop DK, Franklin S, Porsolt RD, Bonsignori A, Carfagna N, McArthur RA. Reboxetine: a pharmacologically potent, selective, and specific norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:818–29. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouda JA, Riga D, De Vries W, Stegeman M, van Mourik Y, Schetters D, Schoffelmeer AN, Pattij T, De Vries TJ. Varenicline attenuates cue-induced relapse to alcohol, but not nicotine seeking, while reducing inhibitory response control. Psychopharmacology. 2011;216:267–77. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]