Abstract

High conductance voltage-and Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Slo1 or BK channels) function in many physiological processes that link cell membrane voltage and intracellular Ca2+, including neuronal electrical activity, skeletal and smooth muscle contraction, and hair cell tuning1–8. Like other voltage-dependent K+ (Kv) channels, BK channels open when the cell membrane depolarizes, but in contrast to other Kv channels they also open when intracellular Ca2+ levels rise. Channel opening by Ca2+ is conferred by a structure called the gating ring, located in the cytoplasm. Recent structural studies have defined the Ca2+-free, closed conformation of the gating ring, but the open conformation is not yet known9. Here we present the Ca2+-bound, open conformation of the gating ring. This structure shows how one layer of the gating ring, in response to the binding of Ca2+, opens like the petals of a flower. The magnitude of opening explains how Ca2+ binding can open the pore. These findings present amolecular basis of Ca2+ activation and suggest new possibilities for targeting the gating ring to treat diseases such as asthma and hypertension.

Regulators of K+ conductance (RCK) domains are ubiquitous among ion channels and transporters in prokaryotic cells10–14. Eight RCK domains assemble in the cytoplasm to form a closed-ring structure that changes its diameter upon ligand binding, thus enabling the ‘gating ring’ to regulate allosterically the transmembrane component of the transport protein. In prokaryotic cells the gating ring most often consists of eight identical RCK domains, arranged as a tetrad of pairs, giving rise to a four-fold symmetric ring with identical top and bottom layers of RCK domains12,15. Intracellular ligands such as Ca2+ or small organic molecules bind in a cleft between RCK pairs forming the top and bottom layers to affect the shape of the ring12,15–17.

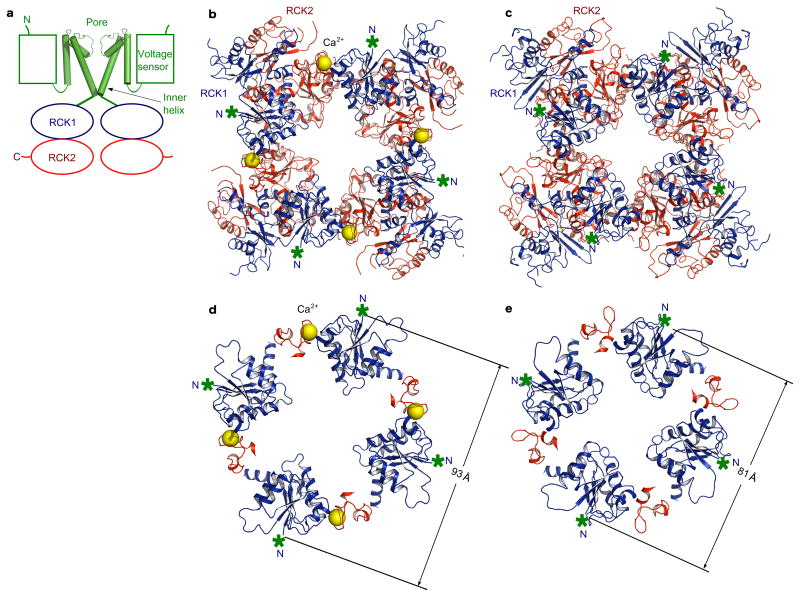

RCK domains are also found in higher eukaryotes in the Slo family of K+ channels9,10,18,19. There, two non-identical RCK domains are encoded in the C-terminus of the K+ channel subunit. A tetrameric K+ channel thus provides eight RCK domains to make a gating ring, but in contrast to most prokaryotic gating rings with identical RCK domains, the eukaryotic gating ring has one kind of RCK domain (RCK1) forming its top layer and another kind (RCK2) forming its bottom layer (figure 1a). A structure of a Ca2+-activated (Slo1 or BK) K+ channel gating ring in its Ca2+-free, closed conformation was recently determined (PDB code 3NAF), as was the structure of an RCK1-RCK2 pair in the presence of Ca2+ (PDB code 3MT5), detailing the chemistry of the Ca2+ binding site9,18. These studies showed that the BK gating ring indeed has distinct top and bottom layers, and also that a Ca2+ binding site known as the Ca2+ bowl is in a different location than the ligand binding site in prokaryotic gating rings. These unique structural properties suggest that in order to regulate conduction, the eukaryotic gating ring may undergo conformational changes in a different manner than its prokaryotic counterpart.

Figure 1. The BK channel and the gating ring.

a, Domain topology of the BK channel. Only two opposing subunits are shown for clarity. b, Crystal structure of the Ca2+-bound open gating ring with RCK1 in blue and RCK2 in red. Ca2+ ions are shown as yellow spheres. The N-termini of RCK1 that connect to the C-termini of the inner helices are indicated as green asterisks. c, Structure of the Ca2+-free closed gating ring with RCK1 in blue and RCK2 in red (PDB: 3NAF). d, The RCK1 N-terminal lobes (blue) and the Ca2+-bowls (red) from the Ca2+-bound open gating ring. The diagonal distance between the Cα atoms of the N-terminal residues (Lys 343) is indicated. e, The corresponding region to that shown in d from the closed gating ring (PDB: 3NAF).

We determined the crystal structure of the Ca2+-bound gating ring from the zebrafish BK channel at 3.6 Å resolution using an expression construct in which a loop consisting of residues 839–872 was deleted (figure 1b, Supplementary Table, and Supplementary Figures 1–2). This loop was disordered in both the Ca2+-free human BK gating ring (3NAF) and the Ca2+-bound RCK1-RCK2 pair (3MT5), and its deletion in both the human and zebrafish BK channels has no detectable affect on function9,18 (Supplementary Figure 3). Therefore, the relative stability of conformational states of the BK gating ring appear to be unaffected by this loop. Initial phases were determined by molecular replacement using the RCK1-RCK2 Ca2+-bound structure as a search model18. The solution showed the presence of eight RCK1-RCK2 pairs(two gating rings) per asymmetric unit of the crystal, which allowed eight-fold noncrystallographic symmetry averaging of electron density maps and eight-fold restraints throughout model refinement. The first step of refinement required rigid body adjustment of the N-terminal lobe of RCK1. The final model was refined to working and free residuals (Rwork and Rfree) of 26.0% and 28.9%, respectively.

The zebrafish channel is 93% identical in amino acid sequence to the human BK channel, for which the Ca2+-free, presumably closed conformation is known (figure 1c and Supplementary sequence alignment)9. The high degree of identity between zebrafish and human BK channels justifies comparison of the two structures to assess potential conformational changes underlying Ca2+-mediated gating. The Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free gating rings are shown (figure 1b,c). In these representations RCK1, which forms the layer of the gating ring closest to the membrane, is colored blue and RCK2 is colored red. In both gating rings a green asterisk marks the N-terminal residue of RCK1, Lys 343. In a full-length BK channel the N-terminal residue of RCK1 is connected by a 16 amino acid linker to the C-terminus of the transmembrane inner helix, which forms the pore’s gate20.

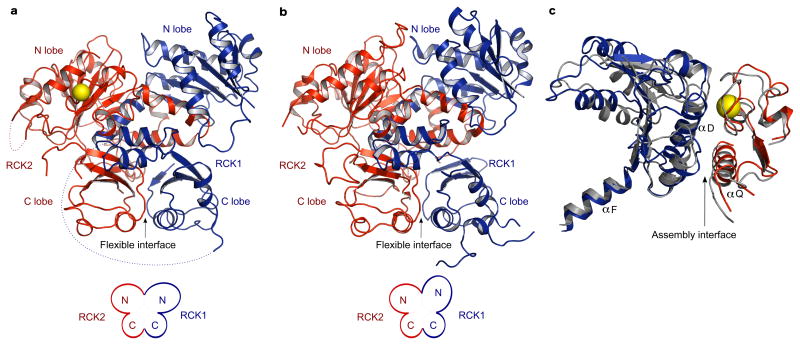

The two gating ring structures, Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free, differ in two main respects. First, in the Ca2+-bound structure electron density attributable to Ca2+ is present in the Ca2+ bowl at the ‘assembly interface’, and second, the RCK1 layer in the Ca2+-bound gating ring is expanded from a diameter of 81 Å to 93 Å, measured at the position of Lys 343 (figure 1d,e and Supplementary Figure 2 c,d). An objective comparison of conformational differences between the Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free gating rings is achieved by superimposing all Cα atoms of the tetrameric gating rings. Such a superposition shows that the RCK2 components of the ring undergo very little change, and only modest conformational differences occur at the assembly interface, except locally near the Ca2+ bowl (figure 2c, Supplementary Figure 4). The Ca2+ bowl structure is nearly identical to that of the Ca2+-bound RCK1-RCK2 pair18 (Supplementary Figure 2e). The major conformational change involves the N-terminal lobe of RCK1, which changes its angle with respect to RCK2 (figure 2a,b, Supplementary Figure 5). Viewing an interpolative movie in which the Ca2+-free gating ring is morphed to the Ca2+-bound gating ring, it appears that Ca2+ binding causes the N-terminal lobes of the RCK1 units to open up on the membrane-facing surface of the gating ring akin to petals opening on a flower (Supplementary Movie 1, part 1).

Figure 2. The flexible and the assembly interfaces.

a, The flexible interface from the open gating ring structure with RCK1 in blue and RCK2 in red. The Ca2+ ions are shown as yellow spheres. The N-and C-terminal lobes of RCK1 and RCK2 are labeled. Large disordered regionsare indicated by dashed lines. b, The flexible interface from the closed gating ring with RCK1 in blue and RCK2 in red (PDB: 3NAF). c, Superposition of the assembly interfaces from the open and the closed gating ring structures.

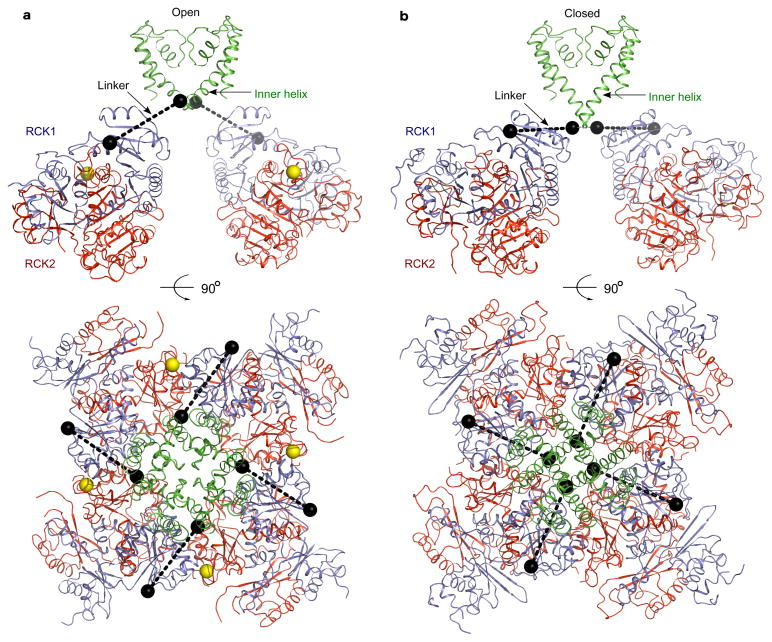

We next analyzed whether these conformational changes are compatible with prior structural data on the opening and closing of K+ channels. We started with the open prokaryotic K+ channel MthK and replaced its gating ring with the Ca2+-bound BK channel gating ring15. This step involved alignment of the four-fold axis followed by minimization of the distance between the BK gating ring N-terminus and the corresponding position of the MthK gating ring through least-squares minimization of residues 343 of BK with the corresponding residues, 116, of MthK. The resulting model of an open BK channel gating ring with an open K+ pore is shown (figure 3a). The distance between the C-terminal residue of the inner helix of the pore and the N-terminal residue of RCK1, which was not a constraint in making the model, is 33 Å. In a second step we replaced the open MthK pore with the closed KcsA pore by aligning the invariant selectivity filter, while also replacing the Ca2+-bound BK channel gating ring with the Ca2+-free BK channel gating ring by aligning the nearly invariant RCK2 layer9,21. The resulting model of a Ca2+-free BK gating ring with a closed K+ pore is shown (figure 3b). In this closed model the distance between the C-terminal residue of the inner helix and the N-terminal residue of RCK1, which again was not a constraint in making the model, is 32 Å. In this analysis the similar pore-to-gating ring distance (~32 Å) in both the open and closed models suggests that the magnitude of conformational change observed within the gating ring is compatible with the magnitude of change known to occur in the pore of other kinds of K+ channels (Supplementary Movie 1 part 2). Whether or not the pore of the BK channel undergoes conformational changes similar to or different than other K+ channels remains to be determined22–26.

Figure 3. A Ca2+-gating model for the BK channel.

a, Views of the BK channel model with an open gating ring and an open pore. Structure of the Ca2+-bound BK gating ring is docked onto the open MthK channel (PDB: 1LNQ) by aligning the gating rings. Yellow spheres represent Ca2+ ions. The N-terminal residues of RCK1 and the C-terminal residues of the inner helices are shown as black spheres. b, Views of the BK channel model with a Ca2+-free gating ring and a closed pore. Here, the Ca2+-bound gating ring in a is replaced by the Ca2+-free gating ring (PDB: 3NAF) and the open MthK pore in a is replaced by the closed KcsA pore (PDB: 1K4C). The innerhelix from KcsA is truncated to match the length in MthK. See Supplementary Movie 1.

Another feature of the model in figure 3 is noteworthy. In the published structure of the Ca2+-free gating ring, part of the linker extending from the gating ring centrally towards the pore was present in the crystal structure and visible on the surface of the gating ring9. The linker was held by a four-helix bundle fused to the N-terminus to facilitate crystallization. Although the linker position in the structure might be affected by this attachment, we note that it runs a course almost coincident with the dashed lines in our closed model (figure 3b). The agreement between the observed linker position in the closed gating ring crystal structure and its inferred position in the closed conformation of our model is an interesting correlation because the radial direction of the linkers in the model (dashed lines) would naturally allow the expansion of the gating ring to exert an opening force on the pore’s inner helices. The idea that the gating ring exerts a direct force on the pore has been proposed on the basis of mutagenesis studies showing that the linker length is critical to efficient Ca2+-mediated gating19,20.

The structural differences between the BK gating ring and the MthK gating ring underlie distinct ligand-induced conformational changes. A higher degree of molecular symmetry in the MthK gating ring stems from its containing eight identical RCK domains12,15. Consequently the MthK gating ring changes equally on both layers so that Ca2+ binding causes a shrinking of its height and an expansion of its diameter (Supplementary Movie 2)12. By contrast, in the BK gating ring Ca2+ binding causes only the layer facing the membrane to undergo a significant conformational change (Supplementary Movie 1). This comparison presents a fascinating example in which the evolution of molecular structure has given rise to new or modified mechanical properties within a class of molecules. Precisely how the free energy of Ca2+ binding in either the BK or MthK gating rings is transduced into mechanical work remains an important outstanding question that will require further experimental and theoretical work to understand at a deep level.

The data and analysis presented here define endpoints in the Ca2+-induced gating conformational transition of the BK gating ring. Given the large conformational change that occurs upon Ca2+ binding it should in principle now be possible to identify small molecules that stabilize one conformation or the other. Such small molecules promise to have important and possibly beneficial physiological effects because BK channels regulate smooth muscle tone in pulmonary airways and vascular beds27–30.

Methods Summary

The cytoplasmic domain (CTD) construct of the zebrafish BK channel including residues 341–1060 with a loop deletion (residues 839–872) was expressed and purified following the same method as described18. However, the size-exclusion chromatography was carried out in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The protein was concentrated to about 6 mg/ml and 10 mM CaCl2 was added before crystallization experiments. Crystals were grown at 20°C using hanging-drop vapor diffusion by mixing equal volumes of protein and a reservoir solution containing 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES), 4% (w:v) PEG 4000, and 100 mM potassium sodium tartrate (pH 6.3). The crystals belong to space group P212121 with cell dimensions of a = 137.65 Å, b = 210.82 Å, c = 238.76 Å and α = β = γ = 90°. Each asymmetric unit contains eight protein subunits forming two gating rings. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using the monomeric Ca2+-bound human BK CTD (PDB code: 3MT5) as the search model. The final model was refined to 3.6 Å resolution with Rwork = 0.260 and Rfree = 0.289. Electrophysiology recordings were conducted using patch-clamp on Xenopus oocytes expressing the wild-type and mutant channels.

Methods

Cloning, expression, and purification

A synthetic gene encoding the zebrafish BK channel (GI: 189526846) was purchased from BioBasic Inc. and served as the template for subcloning. The amino acid sequence is 93% identical to that of the human BK channel. Based on previous structural and functional studies of the human BK channel18, a cytoplasmic domain (CTD) construct including residues 341–1060 with a loop deletion (residues 839–872) was expressed and purified following the same method as described18. However, the size-exclusion chromatography was carried out in 20 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The protein was concentrated to about 6 mg/ml and 10 mM CaCl2 was added to achieve the ligand-bound open conformation before crystallization experiments.

Crystallization and structure determination

Crystals of the zebrafish BK CTD were grown at 20°C using hanging-drop vapor diffusion by mixing equal volumes of protein and a reservoir solution containing 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), 4% (w:v) PEG 4000, and 100 mM potassium sodium tartrate (pH 6.3). The crystals grew to a maximum size of about 0.2 x 0.2 x 0.3 mm3 within three days. Before being flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, the crystals were briefly transferred to a cryoprotectant solution containing 50 mM MES, 6% (w:v) PEG 4000, 100 mM potassium sodium tartrate, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 30% ethylene glycol (pH 6.3). The crystals belong to space group P212121 with cell dimensions of a = 137.65 Å, b = 210.82 Å, c = 238.76 Å and α = β = γ = 90°. Each asymmetric unit contains eight protein subunits.

Diffraction data were measured at beamline X29 from the National Synchrotron Light Source and were processed with the HKL2000 program suite31. The scaled data set was anisotropically corrected to resolution limits of 4.0, 3.6, and 3.6 Å along the reciprocal cell directions a*, b*, and c* respectively, using the diffraction anisotropy server at the University of California, Los Angeles32. An isotropic B factor of −29.98 Å2 was applied to restore the magnitude of the high-resolution reflections diminished by anisotropic scaling. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using the monomeric Ca2+-bound human BK CTD (PDB code: 3MT5) as the search model18. Initial phases were improved by eight-fold noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging carried out with DM from the CCP4 program suite33. Iterative model building was carried out in COOT34. Rounds of refinement were performed with CNS35 and REFMAC36 and strong eightfold noncrystallographic symmetry restraints were maintained throughout refinement. The final model was refined to 3.6 Å resolution with Rwork = 0.260 and Rfree = 0.289. A few disordered regions were not modeled due to weak electron density and the final refined model includes residues 343–571, 581–614, 688–810, 817–837, 875–949,953–1024, and 1029–1059. Residues for which side chain density was poorly defined were modeled as alanines. The majority (95.9%) of the residues lie in the most favored region in a Ramachandran plot, with the remaining 4.1% in the additionally allowed regions. Eight Ca2+ ions were modeled in the Ca2+ bowls from the two gating rings in the crystal. Data collection and structure refinement statistics are shown in Supplementary Table 1. All structural illustrations were prepared with PYMOL (www.pymol.org). The multiple-chain morphing script for CNS37 was used to generate coordinates for the supplementary movies.

Electrophysiology

Channel expression in Xenopus laevis oocytes and electrophysiological recordings in inside-out patches were carried out as previously described18. Wild-type and deletion zebrafish BK constructs were cloned into the pGEM-HE vector38. Plasmids were linearized with PciI and capped cRNA was produced by in vitro transcription from the T7 promoter using the AmpliCap-Max T7 kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies). Xenopus oocytes were injected with ~10ng of cRNA and recordings were made 48–60 hours later. For recording, inside-out patches were excised from freshly devitellinized oocytes using fire-polished glass pipettes with a typical resistance of 1–2 MΩ. In Ca2+-free conditions the bath solution contained 140 mMK-MeSO3, 20mMHepes, 2mMKCl, 5 mM EGTA (final pH: 7.0). For recordings in 10 μM free Ca2+, the same solution was supplemented with 4.83 mM CaCl2, adjusting the pH to 7.0 (we assumed a Kd of 376 nM for the EGTA-Ca2+ complex at pH 7.0). The pipette solution was the same as the Ca2+-free bath solution, but supplemented with 2mM MgCl2. During recording, the membrane voltage was held at −60 mV and currents were elicited by pulsing the voltage from −120 to +140 mV in 10 mV increments (length of pulse: 20 ms). For conductance versus voltage plots, measurements were taken from tail currents at −60 mV,700 μs after the voltage step.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank staff members at NSLS X29, Brookhaven National Laboratory for beamline assistance, and members of the MacKinnon laboratory for discussion. We thank P. Hoff and members of the Gadsby laboratory for help with oocyte preparation. R.M. is an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The research is supported by the American Asthma Foundation grant 07-0127.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions P.Y. purified and crystallized the protein, collected the X-ray diffraction data, determined the structure, and conducted electrophysiology recordings. M.D.L aided in initial crystallization and electrophysiology experiments. Y.H provided assistance with protein expression. P.Y. and R.M. designed the research and analyzed data. P.Y., M.D.L, and R.M. prepared the manuscript.

Atomic coordinates and structure factors for the reported crystal structure have been deposited into the Protein Data Bank under accession code 3U6N. Reprints and permissions information are available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Robitaille R, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ, Charlton MP. Functional colocalization of calcium and calcium-gated potassium channels in control of transmitter release. Neuron. 1993;11:645–655. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fettiplace R, Fuchs PA. Mechanisms of hair cell tuning. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:809–834. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson MT, et al. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner R, et al. Vasoregulation by the beta1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 2000;407:870–876. doi: 10.1038/35038011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petkov GV, et al. Beta1-subunit of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel regulates contractile activity of mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2001;537:443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee US, Cui J. BK channel activation: structural and functional insights. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaczorowski GJ, Knaus HG, Leonard RJ, McManus OB, Garcia ML. High-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels; structure, pharmacology, and function. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1996;28:255–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02110699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:921–931. doi: 10.1038/nrn1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Yang Y, Ye S, Jiang Y. Structure of the gating ring from the human large-conductance Ca(2+)-gated K(+) channel. Nature. 2010;466:393–397. doi: 10.1038/nature09252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Y, Pico A, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Structure of the RCK domain from the E. coli K+ channel and demonstration of its presence in the human BK channel. Neuron. 2001;29:593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albright RA, Ibar JL, Kim CU, Gruner SM, Morais-Cabral JH. The RCK domain of the KtrAB K+ transporter: multiple conformations of an octameric ring. Cell. 2006;126:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye S, Li Y, Chen L, Jiang Y. Crystal structures of a ligand-free MthK gating ring: insights into the ligand gating mechanism of K+ channels. Cell. 2006;126:1161–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakker EP, Booth IR, Dinnbier U, Epstein W, Gajewska A. Evidence for multiple K+ export systems in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3743–3749. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.8.3743-3749.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roosild TP, Miller S, Booth IR, Choe S. A mechanism of regulating transmembrane potassium flux through a ligand-mediated conformational switch. Cell. 2002;109:781–791. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang Y, et al. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417:515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellamacina CR. The nicotinamide dinucleotide binding motif: a comparison of nucleotide binding proteins. FASEB J. 1996;10:1257–1269. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.11.8836039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong J, Shi N, Berke I, Chen L, Jiang Y. Structures of the MthK RCK domain and the effect of Ca2+ on gating ring stability. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41716–41724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan P, Leonetti MD, Pico AR, Hsiung Y, MacKinnon R. Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 A resolution. Science. 2010;329:182–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1190414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pico AR. PhD thesis. The Rockefeller University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niu X, Qian X, Magleby KL. Linker-gating ring complex as passive spring and Ca(2+)-dependent machine for a voltage-and Ca(2+)-activated potassium channel. Neuron. 2004;42:745–756. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y, Morais-Cabral JH, Kaufman A, MacKinnon R. Chemistry of ion coordination and hydration revealed by a K+ channel-Fab complex at 2.0 A resolution. Nature. 2001;414:43–48. doi: 10.1038/35102009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkens CM, Aldrich RW. State-independent block of BK channels by an intracellular quaternary ammonium. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:347–364. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W, Aldrich RW. State-dependent block of BK channels by synthesized shaker ball peptides. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:423–441. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Xia XM, Lingle CJ. Cysteine scanning and modification reveal major differences between BK channels and Kv channels in the inner pore region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12161–12166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104150108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang QY, Zeng XH, Lingle CJ. Closed-channel block of BK potassium channels by bbTBA requires partial activation. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:409–436. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li W, Aldrich RW. Unique inner pore properties of BK channels revealed by quaternary ammonium block. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:43–57. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu RS, Marx SO. TheBK potassium channel in the vascular smooth muscle and kidney: alpha-and beta-subunits. Kidney Int. 2010;78:963–974. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghatta S, Nimmagadda D, Xu X, O’Rourke ST. Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: structural and functional implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miura M, Belvisi MG, Stretton CD, Yacoub MH, Barnes PJ. Role of potassium channels in bronchodilator responses in human airways. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:132–136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones TR, Charette L, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ. Interaction of iberiotoxin with beta-adrenoceptor agonists and sodium nitroprusside on guinea pig trachea. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1879–1884. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Otwinowski Z, Minor W, editors. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. 1997. pp. 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strong M, et al. Toward the structural genomics of complexes: crystal structure of a PE/PPE protein complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8060–8065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potterton E, Briggs P, Turkenburg M, Dodson E. A graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1131–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903008126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the Crystallography and NMR system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Echols N, Milburn D, Gerstein M. MolMovDB: analysis and visualization of conformational change and structural flexibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:478–482. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liman ER, Tytgat J, Hess P. Subunit stoichiometry of a mammalian K+ channel determined by construction of multimeric cDNAs. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.