Abstract

We recently proposed the photoacoustic correlation spectroscopy (PACS) and demonstrated a proof-of-concept experiment. Here, we use the technique for in vivo flow speed measurement in capillaries in a chick embryo model. The photoacoustic microscopy system is used to render high spatial resolution and high sensitivity, enabling sufficient signals from single red blood cells. The probe beam size is calibrated by a blood-mimicking phantom. The results indicate that the feasibility of using PACS to study flow speeds in capillaries.

The smallest of a body’s blood vessels are capillaries, serving the exchange of water, oxygen, carbon dioxide and nutrients between blood cells and surrounding tissues. The flow speeds of red blood cells (RBCs) through capillary networks are affected by various factors such as metabolic demand and heart rate [1,2]. Analysis of capillary flow benefits the disease diagnosis and treatment. For example, study of the alteration of retinal capillary flow velocity may help to identify patients at high risk for cerebrovascular diseases [3].

Current blood velocimeters such as laser Doppler velocimetry and optical/ultrasound particle image velocimetry employ the scattering properties of tracer particles to provide imaging contrast [4]. This dependence on scattering by tracers may limit the sensitivity, resolution, and detection depth due to a high optical scattering coefficient in tissue and much stronger ultrasonic reflection from tissue boundaries than ultrasonic scattering from tracer particles. Recently, PA blood flow speed measurements have received growing attention [5–8]. Previously, PA correlation spectroscopy (PACS) was proposed based on the fluctuation of detected PA signals, analyzed using temporal correlation [7]. A low-speed flow measurement of tracer beads by PACS shows its potential for measuring flow speeds in capillaries.

PACS uses the endogenous light-absorbing tracer particles, RBCs, which can absorb light 100 times more than the background if no other absorbers are within the excitation volume. In the previous work, a pulsed laser without focusing was used, which limited the spatial resolution and sensitivity. Besides, the range of measurable flow speeds was restricted due to low pulse repetition rate. In the current work, we use laser-scanning PA microscopy (PAM) [9] to meet the demanding requirements for speed measurement in capillaries, which, for the first time, facilitated study on biological samples in vivo.

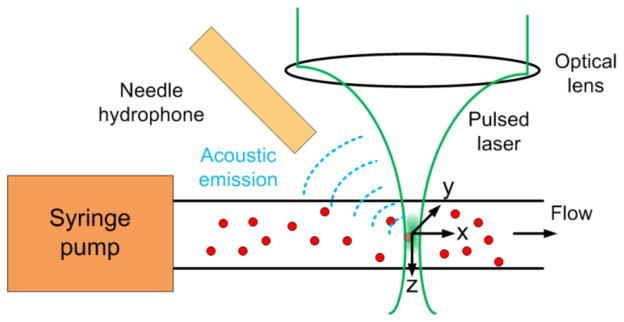

In the laser-scanning optical-resolution PAM system, the ultrasonic detector was kept stationary while the laser was raster scanned by an x-y galvanometer scanner. We used a Nd:YAG laser (Spot-10-200-532, Elforlight Ltd, UK) working at 532 nm wavelength with a pulse duration of 2 ns. A highly sensitive custom-built needle hydrophone with a center frequency of 35 MHz and a 6dB bandwidth of 100% was used for ultrasonic detection and was aligned to the scanned region of laser light. For flow speed measurement, the laser light was positioned and stayed at a designated point on a capillary by controlling the galvanometer fixed at a corresponding angle.

In PACS, PACS strength, P(t), is used, which is defined in Eq. (1) in Ref. [7]. As shown in Fig. 1, when the light-absorbing particles pass through the illuminated volume, PA signals are generated. Because the PA signal A-line is not exactly the same as P(t), the information of P(t) should be extracted from the measured PA signals. Because of the small probe volume from the tight optical focus in the PAM system, the average particle number in the probe volume, N, is small, equal or less than 1. It is appropriate as a simple start, therefore, to use the peak-to-peak PA signal amplitude as P(t), avoiding integration of noise. The calculation of the normalized autocorrelation function (ACF), G(τ), from the P(t) fluctuation has been described in Eq. (2) in Ref. [7]. The decay profile of the G(τ) reveals the particles’ dwell time in the probe volume and the magnitude of G(0) is related to the number density of the beads in the probe region [10].

Fig. 1.

(Color online) Schematic of PACS flow speed measurement using PAM system.

Considering that the focused laser light has a Gaussian distribution in all directions:

where I0 is the peak intensity, x(y) and z are radial and axial position of the laser beam, and r0 and z0 are the radial and axial radii. The Gaussian form in deriving the ACF in flow speed measurement has been studied in FCS [11]. The PACS concept follows from FCS and thus we can simply apply the formula in PACS velocimeter. At the flow speed Vf of tracer particles, the ACF can be expressed as

| (1) |

where τf = r0/Vf and N = 1/G(0).

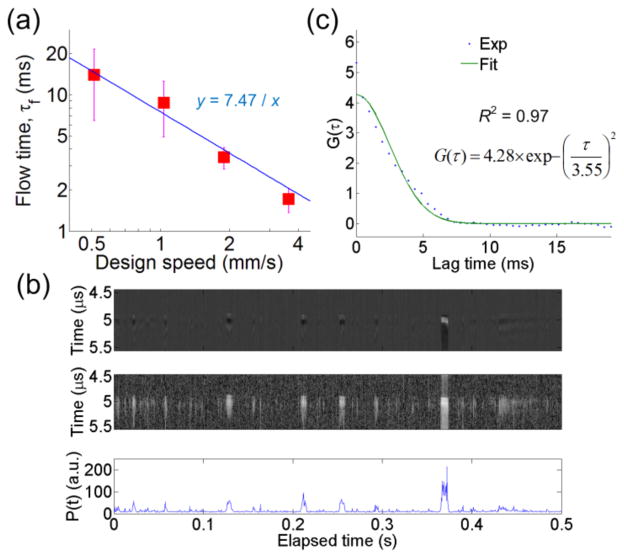

The PACS probe volume using the PAM setup was calibrated by a phantom experiment with known flow speeds, designed from 0.51 to 3.64 mm/s, and particles concentration of φ = 0.2%. The suspended red dyed polybeads (mean diameter: 6.0 μm; Polysciences, Inc.) dispersed in distilled water were used. Beads were flowing, driven by a syringe pump, in a tubing (Inner Diameter: 250 μm, TSP250350, Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ). We first studied the dependence of the autocorrelation decay curves on the flow speeds. Fig. 2(a) plots the flow time, τf, calculated from the fitted autocorrelation curves, versus the designed flow speeds. The flow time becomes shorter as the speed increases. As for extracting τf, we acquired the sequential A-line PA signals (repetition rate 2048 Hz for 2 seconds) and the fluctuation of P(t). One example at Vf = 1.9 mm/s is plotted in Fig. 2(b). Then, the ACFs were calculated and fitted using Eq. (1), as shown in Fig. 2(c). To analyze our data properly, the mean and standard deviation of τf are obtained from at least 4 reliable measurements (the coefficient of determination R2 in the fitting being larger than 0.9) at each flow speed. It is assumed that the small R2 may result from the fact that both one and more-than-one beads are passing through the probe volume during one measurement, which may cause erroneous estimation of τf. Large variations in τf at slower speeds might be due to less chance for beads passing through the probe volume in each measurement compared to that in the high speed case.

Fig. 2.

(Color online) (a) The dependence of the flow time on the design flow speed. The square symbols and the error bars represent the mean flow time and the standard deviations, respectively. The solid line is the curve fitting. (b) The A-line signals (Top), its Hilbert transform displayed over a 50-dB dynamic range for better contrast (Middle), and the P(t) (Bottom). Only the first 0.5 sec is plotted. (c) Calculated and fitted autocorrelation curves in dotted and solid lines, respectively.

To obtain the probe radial beam radius, Fig. 2(a) is fitted using τf = r0/Vf. The extracted r0 is 7.47 μm. For axial beam radius, the average value and standard deviation of G(0) from all valid measurements is 7.18±1.87, and thus N = 0.14. Note that in ACF calculation, the noise in the P(t) estimate was offset to zero for more accurate estimation of G(0) [12]. The noise in P(t) after zero-baseline processing results in underestimation of τf and N, which can be alleviated by improving signal-to-noise ratio. With known sample concentration φ, calculated N, and calibrated r0, the z0 can be estimated as 33.7 μm using φ = (N×Vbead)/Vprobe, where Vbead is the volume of one bead and the probe volume Vprobe = 4/3×πr02z0. Compared to a Gaussian beam calculation, the z0 is smaller, which could be due to a limited directivity of the hydrophone. In the flow measurement, the Brownian motion can be neglected because flow time τf is much shorter than the diffusion time due to Brownian motion, ~several minutes, obtained by a similar analysis in Ref. [7].

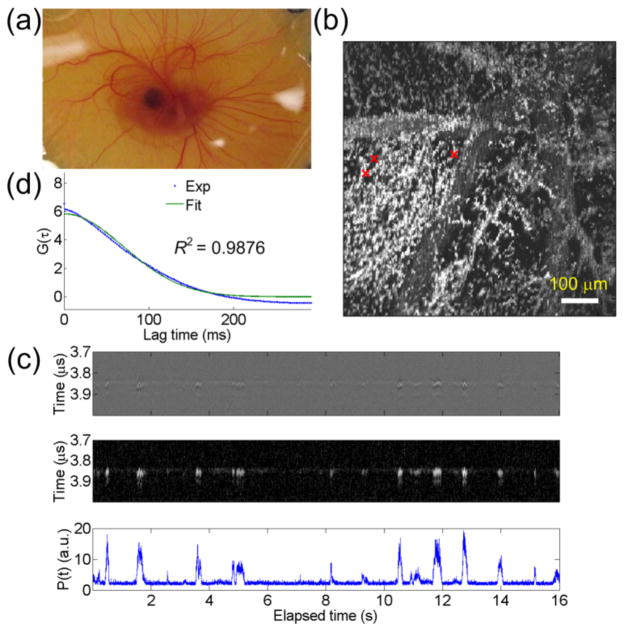

An in vivo experiment was performed on an 8-day-old chick embryo, as shown in Fig. 3(a). The 8-day-old check embryo was used for its mature capillaries [13]. An ex-ovo chick embryo culture method [14] was used for easy experiments. To maintain the life of chick embryo, an infrared lamp was used as a heating resource during the experiment. The membrane around the center of the embryo was first imaged by the PAM system. From the acquired PA image, the positions of capillaries can be recognized. Then, the scanner was positioned so that the probe beam stayed on targeted capillaries for PACS flow speed measurements. The 8192 sequential A scans were obtained at a repetition rate of 512 Hz for 16 seconds. For the statistical analysis, six reliable measurements were used. The data was acquired 40~80 min after the embryo was removed from the incubator. Since RBCs must deform to enter the capillaries, the RBCs length in the capillaries was considered as 16 μm [15] and thus an effective radial beam radius of 10.5 [= (7.472−(6/2)2+(16/2)2)0.5] μm [6] was used for speed calculation. The PACS measured flow time is 53±28 ms. Thus, the calculated flow speed using the effective beam radius is 199 μm/s [~= (10.5 μm) / (53 ms)], which is close to those reported in the literatures [13,15]. The results confirmed that the PACS velocimeter is plausible. Note that without the assumption of RBCs deformation, the calculated speed is 141 μm/s, which is slightly slower but is still reasonable considering the widely ranged flow speeds in capillaries [16]. Verification of RBCs deformation is under investigation.

Fig. 3.

(Color online) (a) Photograph of an 8-day-old chick embryo. (b) The maximum amplitude projection image on x-y plane of the chick embryo. Red crosses: three different positions for flow speed evaluation. (c) The A-line signals (Top), its Hilbert transform displayed over a 25-dB dynamic range (Middle), and the P(t) (Bottom). (d) Calculated and fitted autocorrelation curves in dotted and solid lines, respectively. The fitted τf = 99 ms.

To evaluate the variations of capillary blood flow speeds at different capillary positions, the same embryo was used for measurements. Similarly, we first took the PA image. The maximum amplitude projection image was shown in Fig. 3(b). Three different positions, marked by crosses in Fig. 3(b), were chosen for evaluation. One measured sequential A-line PA signal and its P(t) was shown in Fig. 3(c). The ACFs were shown in Fig. 3(d). The measured flow times are 177±70, 188±37, and 136±53 ms, which are averages from at least four valid measurements for each point. The corresponding flow speeds are 59, 56, and 77 μm/s. Results show that the variation of flow speeds in different capillaries is not obvious. Mildly reduced speeds may be due to the fact that the data was taken ~150 min after removal of the embryo from the incubator, mainly because of the time used for realignment of optical focus for different imaging area. The temperature control by the infrared lamp may not be uniform. Thus, as time elapsed, flow speeds could decrease due to changes of physiologic parameters such as blood pressure.

In summary, PACS for in vivo flow measurement of capillaries in an 8-day-old chick embryo has been demonstrated. We calibrated the probe beam size in the PAM system by a blood-mimicking fluid. PACS is suitable for measuring the capillaries blood speed, which might be unattainable by other PA flow speed measurement methods. Combing with the unique ability of laser-scanning PAM in 3D mapping of microvasculature, PACS provides a promising tool to monitor the disease process. We are also interested in exploring other applications by PACS.

Acknowledgments

Support from NIH Grants EB007619, CA91713, CA91713-S1, and AR055179 is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Qifa Zhou at University of Southern California who provided the hydrophone for the experiments.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Roorda A. Pulsatility of parafoveal capillary leukocytes. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tam J, Tiruveedhula P, Roorda A. Characterization of single-file flow through human retinal parafoveal capillaries using an adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:781–793. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf S, Arend O, Schulte K, Ittel TH, Reim M. Quantification of retinal capillary density and flow velocity in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1994;23:464–467. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vennemann P, Lindken R, Westerweel J. In vivo whole-field blood velocity measurement techniques. Exp Fluids. 2007;42:495–511. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang H, Maslov K, Wang LV. Photoacoustic doppler effect from flowing small light-absorbing particles. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;99:184501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.184501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang H, Wang LV. M-mode photoacoustic particle flow imaging. Opt Lett. 2009;34:671–673. doi: 10.1364/ol.34.000671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S-L, Ling T, Huang S-W, Baac HW, Guo LJ. Photoacoustic correlation spectroscopy and its application to low-speed flow measurement. Opt Lett. 2010;35:1200–1202. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao J, Maslov KI, Shi Y, Taber LA, Wang LV. In vivo photoacoustic imaging of transverse blood flow by using Doppler broadening of bandwidth. Opt Lett. 2010;35:1419–1421. doi: 10.1364/OL.35.001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie Z, Jiao S, Zhang HF, Puliafito CA. Laser-scanning optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt Lett. 2009;34:1771–1773. doi: 10.1364/ol.34.001771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haustein E, Schwille P. Single-molecule spectroscopic methods. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2004;14:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohler RH, Schwille P, Webb WW, Hanson MR. Active protein transport through plastid tubules: velocity quantified by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3921–3930. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.22.3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang Y-C, Ye JY, Thomas T, Chen Y, Baker JR, Norris TB. Two-photon fluorescence correlation spectroscopy through a dual-clad optical fiber. Opt Express. 2008;16:12640–12649. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.012640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belichenko VM, Shoshenko KA. Circulatory system in chicken skeletal muscle in the second half of embryogenesis: Shape, blood flow, and vascular reactivity. Russian J of Developmental Biology. 2009;40:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yalcin HC, Shekhar A, Rane AA, Butcher JT. An ex-ovo chicken embryo culture system suitable for imaging and microsurgery applications. J Vis Exp. 2010;44 doi: 10.3791/2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horn P, Cortese-Krott MM, Keymell S, Kumara I, Burghoff S, Schrader J, Kelm M, Kleinbongard P. Nitric oxide influences red blood cell velocity independently of changes in the vascular tone. Free Radical Research. 2011;45:653–661. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.574288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baumann R, MEUER H-J. Blood oxygen transport in the early avian embryo. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:941–965. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]