Abstract

In the heart, electrical, mechanical, and chemical signals create an environment essential for normal cellular responses to developmental and pathologic cues. Communication between fibroblasts, myocytes, and endothelial cells, as well as the extracellular matrix, are critical to fluctuations in heart composition and function during normal development and pathology. Recent evidence suggests that cytokines play a role in cell–cell signaling in the heart. Indeed, we find that interactions between myocytes and cardiac fibroblasts results in increased interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α secretion. We also used confocal and transmission electron microscopy to observe close relationships and possible direct communication between these cells in vivo. Our results highlight the importance of direct cell–cell communication in the heart, and indicate that interactions between fibroblasts, myocytes, and capillary endothelium results in differential cytokine expression. Studying these cell–cell interactions has many implications for the process of cardiac remodeling and overall heart function during development and cardiopathology.

Keywords: extracellular matrix (ECM), cardiac myocytes, cardiac fibroblasts, endothelial cells, capillaries, development, cardiopathology, interleukin-6, TNF-alpha

Introduction

The cellular organization of the heart consists primarily of myocytes, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells (ECs). In mice, myocytes make up the largest cellular volume, as well as being the most numerous cell type.1 While ECs are confined to the endocardial surface and lining of blood vessels, cardiac fibroblasts are interspersed between the layers of myocytes. Much is known about the organization of the myocytes and the vasculature; however, little is understood about cardiac fibroblasts and their interactions with myocytes and ECs. The development and maintenance of the heart, from inception to death, involves dynamic interactions between the acellular components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the cellular components of the heart. A combination of outside-in and inside-out signaling between the ECM and the cellular components serves to coordinate the development of the myocardium and the fibroblast–connective tissue network, as well as angiogenesis.2–4 This dynamic cellular communication takes place through a combination of mechanical, chemical, and electrophysiologic signals that ultimately regulate heart function.5–7

The cellular populations and ECM of the heart dramatically change throughout embryogenesis and neonatal growth, as well as in the adult, in response to pathophysiologic signals.1,8–13 Morphogenesis of the heart involves the dynamic interactions of embryonically derived cells from different origins to define the overall structure of the heart into ventricular and atrial regions.14 Differentiation continues within these compartments to produce defined structures, such as the trabaeculae, papillary muscles, and different strata of the myocardium. To attain this differentiation, subtle differences in cell–cell and cell–ECM signaling are combined with mechanical force to define these regions.6,15 Pathophysiologic signals are likewise transmitted, and most studies have primarily focused on the role of the cardiac myocytes in the process of differentiation and adaption to various physiologic signals. However, it is now clear that the other cellular components of the heart, principally the fibroblasts and ECs, are also critical to cardiac morphogenesis and remodeling.3,4,6,16 Initially, the heart grows via myocyte proliferation, then primarily by hypertrophy in late neonatal and postnatal rodents.11 In addition, the population ratios of the different cardiac cell types fluctuate during development, as well as during adult pathophysiology,1 which implies differential roles and certain advantages of each cell type.

In recent studies, it has been demonstrated that homotypic interactions between fibroblasts and heterotypic interactions between fibroblasts and myocytes result in the paracrine secretion of regulatory factors that influence myocyte proliferation and other physiologic parameters, such as ECM composition and electrical conductivity.3,5,7,17 In embryonic cardiac cells, fibroblast-secreted fibronectin, collagen, and heparin-binding FGF-like growth factor collaboratively act to promote myocyte proliferation; interestingly, adult fibroblasts did not have the same effect.15 Many studies have shown that interactions between fibroblasts and myocytes are regulated by connexins, as well as other cell–cell molecules.10,12,17–19 In addition, cardiac fibroblasts and collagen content are thought to play key roles in electrophysiologic conductivity and communication between cardiomyocytes.7,20

Cytokines are well-known messengers in cell signaling and regulation of cell behavior, and they maintain this role in cardiac development and remodeling.3,21–23 They are a significant component of the ECM,3,24 and are likely a major avenue through which cells communicate in the heart. Indeed, fibroblast secretion of many paracrine and autocrine factors are increased during cardiac hypertrophy; these factors include interleukin-6 (IL-6), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and angiotensin II (Ang II).25–28

To more closely examine whether interactions between cardiac fibroblasts, myocytes, and ECs result in the secretion of cytokines, we performed three-dimensional cell adhesion assays and analyzed media taken from the cultures of combinations of these cardiac cell populations, in the absence or presence of various blocking antibodies. We also examined these cell–cell interactions in vivo using both confocal and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Materials and methods

Cardiac cell isolation for in vitro studies

Hearts were isolated from neonatal rats, and rat myocytes and fibroblasts were isolated as previously described.29,30 In brief: animals were sacrificed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines, and the hearts were isolated and rinsed in ice-cold Moscona’s solution; they were then placed into Krebs–Ringer buffer I (KRB I) (136 mM NaCL, 28.6 mM KCL, 1.9 mM NaHCO3, 0.08 mM NaHPO4, BSA 1 mg/mL, glucose 2 mg/mL, pen/strep 1 mL, pH 7.4) and minced into small pieces using scissors. Minced tissue was then placed into a sterile 150-mL Erlenmeyer flask and incubated with gentle agitation at 37°C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and the remaining tissue immersed in KRB II solution (KRB I + collagenase type 2 120 U/mL + BSA 20 mg/mL) for subsequent digestions. Supernatants were pooled and filtered through a 40-μM nylon mesh filter. Myocytes were separated from fibroblasts by Percoll gradient purification, as previously described.30,31 Myocytes and fibroblasts were counted using a hemocytometer and plated on aligned collagen as described below. Collagen was aligned onto tissue culture plates as previously described.18,32 In brief: plates were coated with liquid collagen in a tissue culture hood and then allowed to polymerize at 37°C over 30 min, where the collagen could flow gently from top to bottom of the tissue culture dish. This gave the collagen an aligned appearance. Then, 2 × 106 cardiac myocytes were plated onto the aligned collagen dishes (35 mm) to achieve an in vivo, rod-like phenotype.18

Cardioangiography analyses

Adult mice were anesthetized using a ketamine and xylazine cocktail. Hearts were perfused with saline/heparin to clear the vasculature and then with FluroSpheres Red (580/605) (Molecular Probes, F8801, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Hearts were harvested and fixed with fresh 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, for 4 h. 50-μm sections were then cut, stained with Ab1611 (1:100) to visualize the fibroblasts and DAPI (1:5000) to visualize nuclei, and imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) in the Instrumentation Resource Facility at the University of South Carolina.

In vitro cell adhesion assays

Adhesion between cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes was assayed by plating 2 × 106 cardiac myocytes onto aligned collagen on a 35-mm tissue culture dish and allowing them to adhere for 48 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 as described above. After 48 h in culture, 5 × 105 neonatal cardiac fibroblasts were added to the myocyte cultures. Individual dishes were plated for each of the time points, so that the cells would be subjected to minimal agitation. At 4, 8, and 24 h after the addition of fibroblasts, 50 μL of media was withdrawn and viable cells counted using erythrocin blue and a hemocytometer. Data were analyzed by plotting the number of unattached cells as a function of the time point sampled. For studies involving ECs they were plated onto aligned collagen as described above. After 24 h in culture, 5 × 105 neonatal cardiac fibroblasts were added to the endothelial cultures. Individual dishes were plated for each of the time points examined.

For studies involving disruption of cell–cell contacts, we used antibodies against connexin 43 (Cx 43) (50 μg, SC-9059; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), VE-cadherin (25 μg, CP2231; ECM Biosciences, Versailles, KY, USA) or antibodies raised against the cardiac fibroblast plasma membrane, Ab161118 (50 μg for fibroblast–myocyte co-cultures (Fig. 1); 33 μg for fibroblast–endothelial co-cultures (Fig. 2). Cardiac fibroblasts were pre-incubated alone, with IgG, with pre-immune sera or with the respective antibody for 30 min prior to co-culture with either myocytes or ECs.

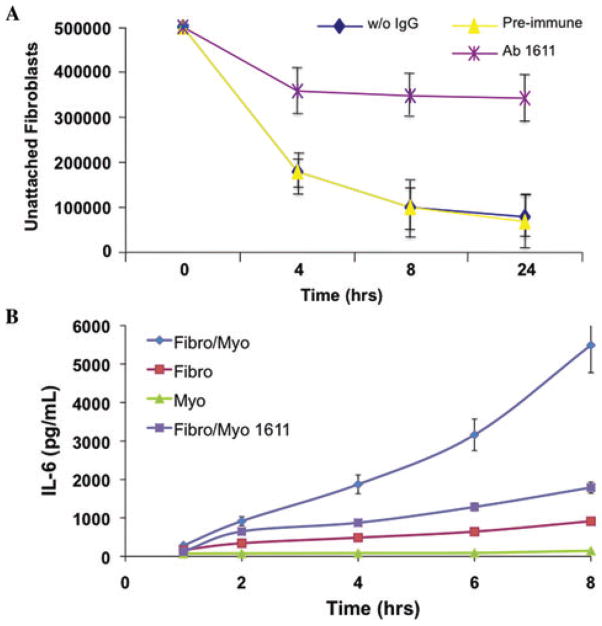

Figure 1.

Antibody 1611 inhibits cardiac fibroblast–myocyte interactions and resultant IL-6 secretion. An antibody against cardiac fibroblast plasma membrane proteins (Ab1611, 50 μg) was added to aligned collagen co-cultures, and resulted in (A) decreased cell adhesion and (B) diminished IL-6 secretion in fibroblast–myocyte co-cultures (P <0.05).

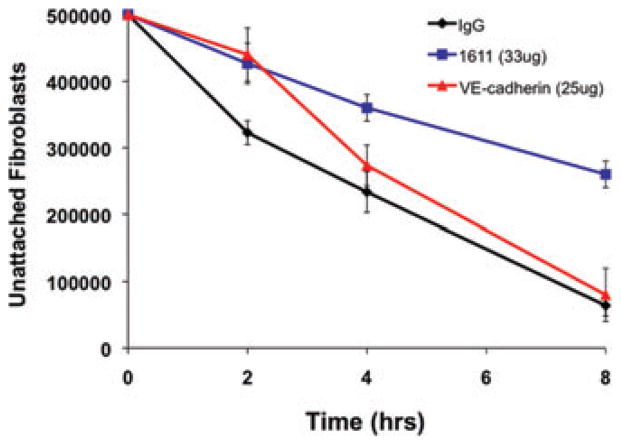

Figure 2.

Cardiac fibroblast–endothelial cell interactions are inhibited by antibody 1611, but not VE-cadherin antibody. Fibroblasts were pre-incubated with either pre-immune serum (IgG control), antibody 1611 (33 μg), or an antibody to VE-cadherin (25 μg), and then co-cultured with endothelial cells. Cell–cell interactions were only blocked in cultures with Ab1611-incubated fibroblasts (P <0.05).

Bioplex cytokine analyses

Whole cell lysates and media samples were collected from cardiac fibroblast, cardiac myocyte, or cardiac fibroblast–myocyte co-cultures as described above. Culture media was sampled at the indicated time points to examine various secreted cytokines and growth factors (including IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α) using the BioRad Bioplex system (Hercules, CA, USA). After collection of all samples, fluorescent beads conjugated to cytokine-specific ligands were incubated with samples in a 96-well plate. The beads were then incubated with a detection antibody and finally with Streptavidin-PE, which reacts with any detection antibody present on the beads. By means of the BioRad Bioplex system, several hundred beads marked for each specific cytokine were measured from each well and the average fluorescence level quantified using a standard curve measured from a known concentration of cytokines. To corroborate the Bio-Plex assay results, Western blot assays were performed to determine the expression of proteins of interest.

Transmission electron microscopy

For TEM, wild-type adult murine hearts (12 weeks old) were isolated, cut into approximately 1–2 mm blocks, rinsed in PBS, and fixed in 4% buffered glutaraldehyde and treated with 2% aqueous osmium tetroxide for 1 h at room temperature, as previously described.33 Hearts were then rinsed, dehydrated, transferred to propylene oxide, embedded, and sectioned. Samples were examined on a JEOL 200CX TEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 160 KV.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from all analyses were measured for significance using Student’s t-test or ANOVA. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Previous studies from our laboratory and those of others have demonstrated that cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes can interact with each other, and that these interactions are regulated by specific proteins, such as integrins, cadherins, and connexins.10,12,18,19 To determine whether direct cell–cell interactions result in the secretion of paracrine and/or autocrine signals, the media obtained from single cultures of cardiac myocytes or fibroblasts and co-cultures of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts were analyzed for a variety of cytokines and growth factors using the Bioplex assay.

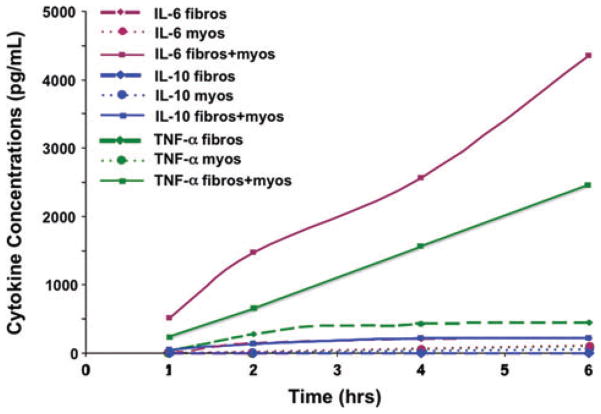

Over a 6-h time period, IL-6 was expressed only in the culture media of cardiac fibroblast–myocyte co-cultures. In addition, there was negligible secretion of IL-10; however, TNF-α was highly expressed in cardiac fibroblast–myocyte co-cultures, as well as being expressed at low levels in fibroblast-only cultures (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

IL-6 and TNF-α expression are increased in co-cultures of cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes. Aligned collagen cultures of cardiac fibroblasts or myocytes alone did not result in increased cytokine expression; however, co-cultures resulted in increased IL-6 and TNF-α concentrations in the media (P <0.05). IL-10 expression was not increased in any of the cultures or co-cultures.

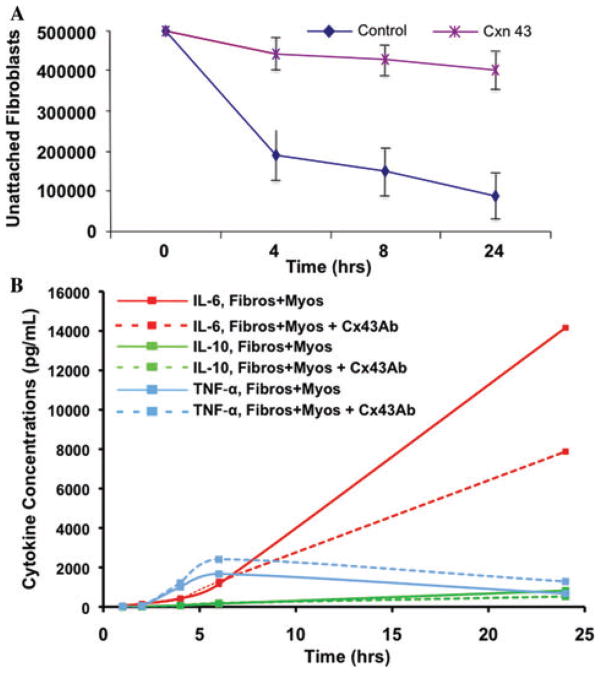

To determine whether the secretion of either IL-6 or TNF-α could be altered by blocking cell–cell interactions, myocytes were co-cultured with cardiac fibroblasts that had previously been incubated with blocking antibodies against connexin 43 (Cx43). As previously demonstrated,18 the addition of Cx43 antibodies to the co-cultures disrupted myocyte–fibroblast interactions (Fig. 4). When these cell–cell interactions were disrupted, the concentration of IL-6 in the media was markedly reduced (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, TNF-α secretion was actually increased in the co-cultures that had been treated with antibodies against Cx43 (Fig. 4B). We have also previously demonstrated that our 1611 antibody, raised against cardiac fibroblast plasma membrane, can disrupt cardiac fibroblast–myocyte interactions.18 Therefore, we examined whether disruption of cell–cell interactions using Ab1611 displayed the same effect on IL-6 expression as Cx43 blocking antibodies. Indeed, addition of Ab1611 caused inhibition of cardiac fibroblast–myocyte interactions, as well as a significant decrease in IL-6 secretion into the media (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 4.

Connexin 43 inhibits cardiac fibroblast–myocyte interactions and resultant IL-6 secretion. The addition of connexin 43 antibody (Cx43, 50 μg) to aligned collagen cardiac fibroblast–myocyte co-cultures, but not cultures of either cell type alone, resulted in (A) decreased cell adhesion and (B) IL-6 secretion (P < 0.05). Cx43 is a major route by which cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes communicate, and is involved in a mechanism of IL-6 secretion.

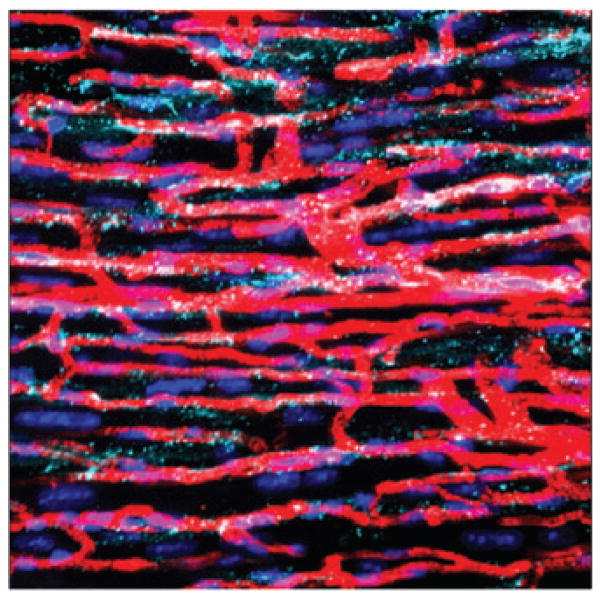

Having examined, and inhibited, interactions between cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes, we next analyzed adhesion cultures of cardiac fibroblasts and ECs. As observed in cardiac fibroblast–mycocyte co-cultures, Ab1611 was also able to inhibit cardiac fibroblast–EC interactions; however, these interactions were not affected when treated with blocking antibodies against VE-cadherin (Fig. 2). Given these observed interactions between ECs and fibroblasts in vitro, we wanted to examine whether these interactions were also occurring in vivo. We performed fluorescent cardioangiography to assess the in vivo relationship between cardiac fibroblasts and the vasculature. We stained with DAPI to visualize cell nuclei, and to demark the cardiac fibroblasts from other cardiac cell types, we also stained with Ab1611. Confocal microscopy showed a close association between cardiac fibroblasts and the capillaries of the heart (Fig. 5). As previously described,18,34 staining with Ab1611 showed that the cardiac fibroblasts were not only in apparent contact with the vessels, but also extended into the extracellular space.

Figure 5.

Cardiac fibroblasts are closely associated with capillaries in vivo. Mice were perfused with fluorescent microspheres; the hearts were collected and sectioned at 50-μm intervals, and stained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (dark blue) and 1611 to visualize fibroblasts (teal): the perfused microspheres fill the capillaries (red). Note the close association between the fibroblast extensions and the vasculature, as well as the extracellular space.

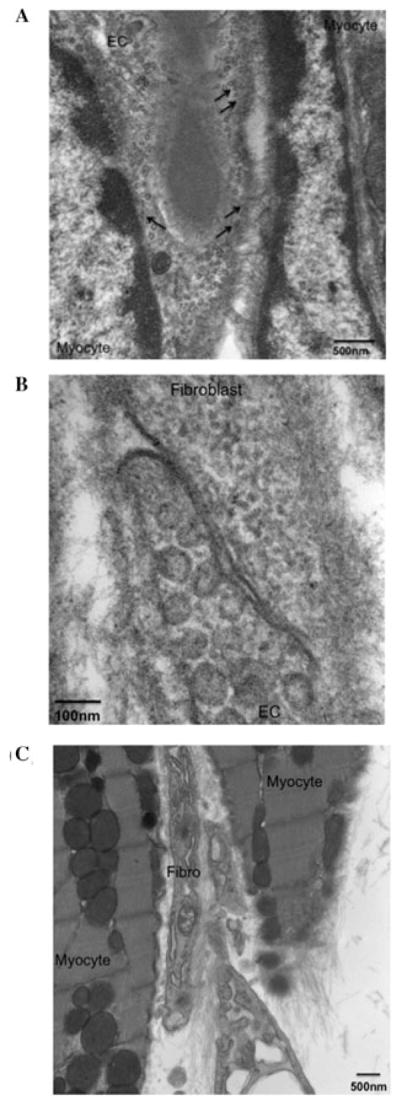

Transmission electron microscopy was used to determine whether myocytes were in contact with capillaries, and if fibroblasts in the extracellular space were in contact with each other, with myocytes, the ECM and/or with ECs and capillaries, as previously proposed by Baudino and colleagues.18 TEM of an area similar to that observed in Figure 5 indicates that capillaries are tightly apposed to the myocyte (Fig. 6A). The ECs displayed numerous pinocytotic vesicles that appear to be in contact with the plasma membrane of the myocyte (Fig. 6A; black arrows).

Figure 6.

Cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells are in direct association with one another. TEM imaging of adult mouse hearts illustrates close relationships between myocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (ECs). (A) Myocytes and EC; black arrows denote endothelial microvesicles that are in contact with the adjacent myocytes, as is confirmed by stereomicroscopic analyses (not shown); scale bar is 500 nm. (B) Fibroblasts and EC; scale bar is 100 nm. (C) Myocytes and fibroblasts; scale bar is 500 nm. Cells in such close proximity have several avenues by which they communicate, including gap junctions and the ECM, which can be visualized in these photomicrogaphs.

Stereomicroscopic examination of these interactions confirms that these endothelial microvesicles are indeed in direct contact with the myocytes (data not shown). Further analyses also demonstrated that fibroblasts are in close contact with both ECs of the capillaries of the heart (Fig. 6B) and with myocytes (Fig. 6C).

Discussion

The results of the current study highlight the importance of direct cell–cell communication in the heart, and indicate that interactions between cardiac fibroblasts, myocytes, and the capillary endothelium result in differential cytokine expression. Aside from low levels of IL-6 secretion by fibroblasts (Fig. 1), only co-cultures of cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes resulted in significant cytokine secretion (Figs. 1, 3, and 4). As previously observed,18 interactions between cardiac fibroblasts and myocytes are a necessary component of in vitro cytokine secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig. 4). The inhibition of cardiac fibroblast–myocyte interactions through Cx43 antibody depleted IL-6 secretion, but increased TNF-α expression (Fig. 4). Both IL-6 and TNF-α have been reported to induce an increase in fibroblast collagen transcripts and synthesis.28 Secretions from cardiac fibroblasts have also been shown to increase myocyte hypertrophy and induce cardiac remodeling,35 and the current results fall in line with these previous studies. Interestingly, clinical studies report an increase in TNF-α during hypertrophy, which has been implicated in myocyte apoptosis, as well as an array of cardiovascular diseases.36,37 As discussed, cell–cell communication is altered during cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling, and our data indicate that a decrease in these critical cell–cell interactions (e.g., via apoptosis or increased collagen deposition) can be associated with the increased levels and adverse effects of TNF-α seen in pathologic conditions. It is also clear from the current studies that cytokine release is coordinated, rather than sporadic or nonspecific, as evidenced by a lack of IL-10 or other anti-inflammatory cytokine release. Studies are under way to more closely examine secretions that result from interactions between all three cell types, as well as how wound healing, cell migration, and cardiac remodeling are altered by these cytokine secretions.

IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine that regulates biological functions in a cell- and tissue-specific manner, including in the heart. Accumulating evidence suggests that IL-6 and its effector pathways, specifically the gp130/Jak-STAT pathway, are critical in myocardial function and cardioprotection.25,38,39 Our lab has recently observed differential cardiac cell population ratios, specifically an increase in the number of cardiac fibroblasts and collagen deposition, a subsequent reduction in EC and smooth muscle cell populations and altered coronary vasculature in the hearts of IL-6 knockout mice.40 Furthermore, clinical reports show that circulating members of the IL-6 cytokine family are often increased following myocardial infarction and in patients with congestive heart failure.41 Results from the current study showing increased IL-6 secretion as a result of heterotypic cell–cell communication further support an important role for IL-6 in both normal cardiac function and pathologic conditions.

While Cx43 was important for efficient cardiac cell–cell interactions, it was not entirely responsible for IL-6 secretion (Fig. 4B). Likewise, the inhibition of cardiac fibroblast–myocyte interactions by Ab1611 resulted in diminished, rather than abolished, IL-6 secretion (Fig. 1). It is logical to conclude that additional membrane surface receptors and proteins, and likely soluble cell signaling factors, are involved in these cell–cell interactions and signaling. Undoubtedly, the ECM is a critical element in both cell adhesion and signaling in vivo, and further investigation into the roles of the various ECM components is essential for the complete understanding of cell interactions in the heart.

Confocal and TEM imaging allowed for the visualization of the fibroblast–myocyte–EC interactions in question. It is clear from these images that these cell types are very closely associated with one another in vivo and, as represented by the endothelial microvesicles in Figure 6A, can directly communicate with one another. Even in regions where cell membranes do not form tight junctions, ECM fibers are obvious and seem to link these cells, and likely play an integral role in cell communication (Figs. 6A–C). The confocal image in Figure 5 shows association of cardiac fibroblasts and the capillary bed, as well as the apparent extracellular space; these observations are confirmed in TEM imaging. Both ECM and tight junctions between a fibroblast and EC are apparent in Figure 6B. Because it can be beneficial for a cardiac cell to be responsive to different types of signals (i.e., mechanical, electrical, and chemical), and to properly differentiate these signals, diverse avenues of communication are necessary, and include interactions through gap junctions, vesicle delivery, and cytokines and growth hormones, in addition to a variety of ECM-mediated signaling.2–4 All of these avenues of communication are illustrated in the current study.

Cardiac myocytes vary in size and shape depending on their location within the heart, the stage of development, as well as in response to pathophysiologic signals.42 A modification in the size or arrangement of myocytes logically demands a correction in the distribution of factors that are critical to cell survival, which is commonly mediated through capillary distribution. Angiogenesis is directly affected by the metabolic demands of the heart, and its regulation is coordinated via cell–cell contacts with myocytes, fibroblasts, ECs, and the ECM. Cytokines and ECM factors have been shown to be critical for vascular remodeling and regulation in cardiac and noncardiac tissues.4,43,44 Interestingly, dermal fibroblasts were recently found to be a more potent factor than VEGF for in vitro endothelial tube/vessel formation.45 The combined result of these heterogeneous cellular and acellular interactions is detrimental to the electromechanical and physical properties of the heart, and, therefore, heart function.

The myriad of changes that occur during development and pathology are not independent of each other, but instead are largely influenced by one another. During normal growth, cellular, electrical, and chemical changes are balanced in relation to cardiac function. However, during pathophysiologic conditions, an imbalance in these signals contributes to altered ECM content and deposition, an expansion of the vascular compartment and an increase in the non-myocyte components of the heart. The resultant remodeling changes the cellular environment and leads to alterations in cardiac function. The present studies demonstrate that cardiac cell communication is critical to the chemical signals involved in cardiac remodeling, and warrants further investigation. Defining the signals responsible for altered cell communication will lend insight into the cardiac developmental process, as well as the etiology and treatment of cardiac disease.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Indroneal Banerjee and Arti Intwala for their technical support. These studies were funded in part by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants 1RO1-HL-85847and AHA SDG 0830268N.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Banerjee I, et al. Determination of cell types and numbers during cardiac development in the neonatal and adult rat and mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1883–H1891. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00514.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross RS, Borg TK. Integrins and the myocardium. Circ Res. 2001;88:1112–1119. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldsmith EC, Borg TK. The dynamic interaction of the extracellular matrix in cardiac remodeling. J Card Fail. 2002;8:S314–S318. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2002.129258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis GE, Senger DR. Extracellular matrix mediates a molecular balance between vascular morphogenesis and regression. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:197–203. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282fcc321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudino TA, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts: friend or foe? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1015–1026. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00023.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohl P. Heterogeneous cell coupling in the heart: an electrophysiological role for fibroblasts. Circ Res. 2003;93:381–383. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091364.90121.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachse FB, Moreno AP, Abildskov JA. Electrophysiological modeling of fibroblasts and their interaction with myocytes. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:41–56. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markwald RR. The role of extracellular matrix in cardiogenesis. Tex Rep Biol Med. 1979;39:249–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borg TK, et al. Recognition of extracellular matrix components by neonatal and adult cardiac myocytes. Dev Biol. 1984;104:86–96. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong MT, Armstrong PB. Mechanisms of epibolic tissue spreading analyzed in a model morphogenetic system. Roles for cell migration and tissue contractility. J Cell Sci. 1992;102(Pt 2):373–385. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong MT, Lee DY, Armstrong PB. Regulation of proliferation of the fetal myocardium. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:226–236. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dvdy1049>3.3.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camelliti P, Borg TK, Kohl P. Structural and functional characterisation of cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris RA, et al. Neonatal and adult cardiovascular pathophysiological remodeling and repair: developmental role of periostin. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:30–40. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tam PPL, Schoenwolf GC. In: Heart Development. Harvey RP, Rosenthal N, editors. Academic Press; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ieda M, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaFramboise WA, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts influence cardiomyocyte phenotype in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C1799–C1808. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00166.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sussman MA, McCulloch A, Borg TK. Dance band on the Titanic: biomechanical signaling in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2002;91:888–898. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000041680.43270.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baudino TA, et al. Cell patterning: interaction of cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts in three-dimensional culture. Microsc Microanal. 2008;14:117–125. doi: 10.1017/S1431927608080021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong PB. Ability of a cell-surface protein produced by fibroblasts to modify tissue affinity behaviour of cardiac myocytes. J Cell Sci. 1980;44:263–271. doi: 10.1242/jcs.44.1.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudesius G, et al. Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circ Res. 2003;93:421–428. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089258.40661.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jaffre F, et al. Involvement of the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor in cardiac hypertrophy linked to sympathetic stimulation: control of interleukin-6, interleukin-1beta, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha cytokine production by ventricular fibroblasts. Circulation. 2004;110:969–974. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139856.20505.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoyama T, et al. Angiotensin II and mechanical stretch induce production of tumor necrosis factor in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1968–H1976. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue P, et al. Post-infarction heart failure in the rat is associated with distinct alterations in cardiac myocyte molecular phenotype. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1615–1630. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corda S, Samuel JL, Rappaport L. Extracellular matrix and growth factors during heart growth. Heart Fail Rev. 2000;5:119–130. doi: 10.1023/A:1009806403194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumgarten G, et al. Load-dependent and -independent regulation of proinflammatory cytokine and cytokine receptor gene expression in the adult mammalian heart. Circulation. 2002;105:2192–2197. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015608.37608.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komuro I. Molecular mechanism of cardiac hypertrophy and development. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:353–358. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakatsuki T, Schlessinger J, Elson EL. The biochemical response of the heart to hypertension and exercise. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkar S, et al. Influence of cytokines and growth factors in ANG II-mediated collagen upregulation by fibroblasts in rats: role of myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H107–H117. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiraishi I, et al. Vinculin is an essential component for normal myofibrillar arrangement in fetal mouse cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2041–2052. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bullard TA, Borg TK, Price RL. The expression and role of protein kinase C in neonatal cardiac myocyte attachment, cell volume, and myofibril formation is dependent on the composition of the extracellular matrix. Microsc Microanal. 2005;11:224–234. doi: 10.1017/S1431927605050476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp WW, et al. Mechanical forces regulate focal adhesion and costamere assembly in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H546–H556. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson DG, et al. Modulation of cardiac myocyte phenotype in vitro by the composition and orientation of the extracellular matrix. J Cell Physiol. 1994;161:89–105. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041610112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa M, et al. Analysis of heart development in cultured rat embryos. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:369–379. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldsmith EC, et al. Organization of fibroblasts in the heart. Dev Dyn. 2004;230:787–794. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sano M, et al. Interleukin-6 family of cytokines mediate angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in rodent cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29717–29723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meldrum DR. Tumor necrosis factor in the heart. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R577–R595. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crow MT, et al. The mitochondrial death pathway and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circ Res. 2004;95:957–970. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148632.35500.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamimura D, Ishihara K, Hirano T. IL-6 signal transduction and its physiological roles: the signal orchestration model. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;149:1–38. doi: 10.1007/s10254-003-0012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsushita K, et al. Interleukin-6/soluble interleukin-6 receptor complex reduces infarct size via inhibiting myocardial apoptosis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1210–1223. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banerjee I, et al. IL-6 loss causes ventricular dysfunction, fibrosis, reduced capillary density and dramatically alters the cell populations of the developing and adult heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1694–H1704. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00908.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirota H, et al. Circulating interleukin-6 family cytokines and their receptors in patients with congestive heart failure. Heart Vessels. 2004;19:237–241. doi: 10.1007/s00380-004-0770-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holmes JW, Borg TK, Covell JW. Structure and mechanics of healing myocardial infarcts. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:223–253. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson JT, et al. Evolution of matrix metalloprotease and tissue inhibitor expression during heart failure progression in the infarcted rat. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:307–315. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yan SF, et al. Hypoxia-induced modulation of endothelial cell properties: regulation of barrier function and expression of interleukin-6. Kidney Int. 1997;51:419–425. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, Chen B, Lilly B. Fibroblasts potentiate blood vessel formation partially through secreted factor TIMP-1. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:223–234. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]