Abstract

Context:

The overwhelming majority of benign lesions of the adrenal cortex leading to Cushing syndrome are linked to one or another abnormality of the cAMP or protein kinase pathway. PRKAR1A-inactivating mutations are responsible for primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease, whereas somatic GNAS activating mutations cause macronodular disease in the context of McCune-Albright syndrome, ACTH-independent macronodular hyperplasia, and, rarely, cortisol-producing adenomas.

Objective and Design:

The whole-genome expression profile (WGEP) of normal (pooled) adrenals, PRKAR1A- (3) and GNAS-mutant (3) was studied. Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot were used to validate WGEP findings.

Results:

MAPK and p53 signaling pathways were highly overexpressed in all lesions against normal tissue. GNAS-mutant tissues were significantly enriched for extracellular matrix receptor interaction and focal adhesion pathways when compared with PRKAR1A-mutant (fold enrichment 3.5, P < 0.0001 and 2.1, P < 0.002, respectively). NFKB, NFKBIA, and TNFRSF1A were higher in GNAS-mutant tumors (P < 0.05). Genes related to the Wnt signaling pathway (CCND1, CTNNB1, LEF1, LRP5, WISP1, and WNT3) were overexpressed in PRKAR1A-mutant lesions.

Conclusion:

WGEP analysis revealed that not all cAMP activation is the same: adrenal lesions harboring PRKAR1A or GNAS mutations share the downstream activation of certain oncogenic signals (such as MAPK and some cell cycle genes) but differ substantially in their effects on others.

The majority of benign lesions of the adrenal cortex leading to Cushing syndrome are linked to one or another abnormality of the cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling pathway (1–3). Inactivating mutations of the PRKAR1A gene coding for the regulatory 1α-subunit of PKA are responsible for Carney complex (CNC) in the majority of patients (4). Primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD) is the most common endocrine tumor associated with CNC, leading to Cushing syndrome in more than 60% of the patients (4). Micronodular adrenocortical hyperplasias and some cortisol-producing adenomas are associated with phosphodiesterase (PDE) 11A and phosphodiesterase 8B defects, coded, respectively, by the PDE11A and PDE8B genes (5–8).

Somatic GNAS mutations have been described only in a small number of both ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia (AIMAH), also known as massive macronodular adrenocortical disease (MMAD), rarely in cortisol-producing adenomas (3, 9), and in the context of McCune-Albright syndrome. cAMP/PKA signaling is altered in MMAD as in adrenal tumors with 17q losses or PRKAR1A mutations (1, 10). Furthermore, common adrenal lesions without germline or somatic GNAS, PRKAR1A, PDE11A, and PDE8B mutations and associated with ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome (CS) had functional abnormalities of the cAMP signaling pathway, such as increased cAMP levels, decreased total PDE, and/or increased PKA activity (2). Thus, aberrations of cAMP/PKA signaling are essential in the pathogenesis of benign cortisol-producing lesions of the adrenal cortex.

Previous transcriptome studies demonstrated the overexpression of genes that regulate or are part of the Wnt signaling pathway in both PPNAD and MMAD without GNAS mutations (11, 12). In agreement with these findings, a whole-genome transcriptome profiling of tumors produced by mouse models of Prkar1a haploinsufficiency identified Wnt signaling as the main pathway activated by abnormal cAMP signaling along with cell cycle abnormalities (13).

In this study, we analyzed the whole-genome expression profile (WGEP) of PPNAD caused by germline PRKAR1A mutations and adrenal lesions harboring somatic GNAS mutations. The data indicated that cAMP activation in adrenal lesions harboring PRKAR1A or GNAS mutations share the downstream activation of some oncogenic signals but differ significantly in their effects on others. These findings are important for the design of molecularly targeted therapies for benign adrenal tumors or hyperplasias leading to CS.

Patients and Methods

Subjects, tissues, DNA studies, and sequencing

Patients were studied under protocols 95CH0059 and 00CH160, both approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). We studied two groups of lesions (Table 1): group 1 included three microdissected PPNAD samples from patients with CNC caused by three different nonsense PRKAR1A mutations (see text below); and group 2 included three microdissected samples from adrenal lesions that were all caused by the same somatic GNAS mutation (p.R201H): a cortisol-producing adenoma from a patient with AIMAH/MMAD and CS and two microdissected adenomatous nodules from a patient with MAS and CS (Supplemental Material, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data from patients with PPNAD and adrenal masses with GNAS mutation

| Patient code | Adrenal disease | Age at diagnosis | UFC (8–88 μg per 24 h) | Midnight cortisol (<1.8 μg/dl) | After high dose Dex/after Liddles's urinary costisola | Imaging | Other tumors/conditions | Gene | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR47.01 | PPNAD | 31 yr | 24.5 | 5.5 | 180.6 μg per 24 h | Suggestive of nodular disease | Left atrial myxoma/multiple ischemic strokes | PRKAR1A | c.177 + 1G>A |

| CAR21.02 | PPNAD | 20 yr | 226.4 | 11.1 | 12.1 μg/dl (serum) | Two right adrenal masses (the largest 2 × 1.5 cm)/enlargement of left adrenal gland | Liver tumors (hepatocellular adenoma), pituitary GH- secreting microadenoma, depression | PRKAR1A | c.101_105delCTATT/p.Ser34fsX9 |

| CAR20.14 | PPNAD | 13.8 yr | 25 | 5.8 | 110 μg per 24 h | Suggestive of nodular disease | Recurrent atrial myxomas | PRKAR1A | c.491_492delTG/p.Val164fsX4 |

| ADTLG01 | AIMAH/MMAD | 30 yr, recurrence at 36 yr | 103 | 7.6 | 8.3 μg/dl | 2 cm right adrenal tumor/2.2 cm left adrenal tumor | No | GNAS | R201H |

| CAR588.03 | McCune-Albright syndrome | 1 month | NA | NA | NA | Bilateral adrenal enlargement with numerous small nodules | Thyrotoxicosis, diabetes, café-aux-lait spots, fibrodysplastic lesions | GNAS | R201H |

NA, Not available; UFC, urinary free cortisol; Dex, dexamethasone.

High-dose Dex: overnight 8 mg dexamethasone test, Liddles's 6-d test.

All tissue samples were carefully dissected out of surrounding periadrenal fat, adrenal capsule, and other structures. In tissues with GNAS mutations, only cortical nodular tissue that was previously sequenced and found to contain the p.R201H mutation was used for the RNA studies. In the case of PPNAD, all samples contained the PRKAR1A mutation in the heterozygote state; special attention was paid to not include RNA from PRKAR1A-haploinsufficient nodules [those that have undergone loss of heterozygosity (LOH) for the 17q22-24 locus of PRKAR1A] because these tissues may have additional genetic and transcriptome changes. Sequencing for the PRKAR1A and GNAS genes was done as has been described elsewhere (9, 10). The three PRKAR1A mutations were c.177 + 1G>A, c.101_105delCTATT, and c.491_492delTG, respectively; they all lead to predicted truncated proteins and their mRNA undergo nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) and are not expressed (4).

Microarray analysis

Total RNA extraction was performed from all tissues using the Trizol reagent method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were further purified using the RNeasy columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), and the quality of RNA was assessed using the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Three commercially available pools of human adrenal total RNA (CLONTECH, Mountain View, CA; BioChain, Hayward, CA; Ambion, Austin, TX) were used as reference samples. The normal reference RNA that was used was total adrenal-derived RNA. Preparation of cRNA from total RNA, hybridization in Sentrix HumanRef-8 Expression BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA), scanning, and image analysis was done as previously described (14). Analysis of Illumina data were performed using Illumina BeadStudio software (Illumina), which returns the trimmed mean average intensity for each single gene probe type (nonnormalized). Any gene consistently with a P detection value above 0.01 for all samples was eliminated from further analysis. Z-transformation for normalization was performed for each Illumina sample/array (14). First, the raw intensity data for each sample were log10 transformed, and Z scores were calculated by subtracting the overall average gene intensity (within a single experiment) from the raw intensity data for each gene and then dividing that result by the sd of all of the measured intensities. Changes in gene expression (ratio) between different Z-transformed data sets (nodules compared with the average of the normal adrenal pools) were calculated as differences between the corresponding Z scores and then divided by the sd of each Z difference data set (14). A 2-fold change was used as the cutoff value to identify over- and underexpressed genes in adrenal nodules in relation to normal adrenal pools. Microarray data are in compliance with the Minimal Information About a Microarray Experiment format. The raw and normalized microarray data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE 33694).

Analysis of mRNA profiling and validation

The WGEP was analyzed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Bioinformatic Resources 2008 (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (15, 16). The lists of genes (induced or repressed) were submitted to the DAVID database genes are clustered according to a series of common key words. The proportion of each key word in the list is compared with the one in the whole genome, making it possible to compute P values and enrichment scores (geometric mean of the inverse log of each P value). The detailed information of gene alterations was systematically reported on Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEEG) pathways.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector using PCR array plates (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) and TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The assay identifications were: NFKB1, Hs00765730_m1; RAB13, Hs00762784_s1; RAPGEF4 (EPAC2), Hs00899815_m1; BMP4, Hs00370078_m1; and 18S rRNA, 4352930E. The average of three commercially available pools of human adrenal total RNA (CLONTECH, BioChain, and Ambion) was used as control. Relative quantification was performed using the 2−ΔΔCT method (17).

Protein studies

Western blot analysis was performed following standard procedures (13). The following primary antibodies were used: beta catenin (CTNNB1; 9587; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), nuclear factor-κB (NFKB; ab16502; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), inhibitory-κB (IKBa; ab32518; Abcam), renin-angiotensin system oncogene family 13 (RAB-13; ab55889; Abcam), and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; ab9485; Abcam). All immunohistochemistry was performed at Histoserve, Inc. (Germantown, MD) using standard procedures. The following primary antibodies were used: CTNNB1 (9587; Cell Signaling), NFKB (ab16502; Abcam), and IKBa (ab32518; Abcam). The following grading system was used for staining evaluation: negative (absence of expression), weak staining (from 1 to 25% of immunoreactive cells), and strong staining (>25% of immunoreactive cells). We also measured the PKA enzymatic activity in tissue extracts as previously described (18).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Continuous data are expressed as mean ± sd. All the experiments were performed in triplicate. A two-sample t test was used for paired samples. We considered a P < 0.05 significant for all comparisons.

Results

Transcriptome analysis, validation, and PKA activity

The gene set enrichment analysis of the WGEP revealed that signaling for P53 and MAPK was significantly enriched in both PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions. Adrenal masses with GNAS mutations were significantly enriched with extracellular matrix (ECM) receptor interaction and focal adhesion pathways when compared with PPNAD (fold enrichment 3.5, P < 0.0001, and 2.2, P < 0.002, respectively) (Fig. 1A). The overexpressed genes in GNAS-mutant lesions compared with those with the PRKAR1A mutations included NFKB1 [nuclear factor of κ-light polypeptide gene enhancer in B cells 1; ratio (log10) 4.2, P = 0.004], ELK1 (member of the ETS oncogene family; ratio 3.0, P = 0.03), LPAR1 (lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1; ratio 12.6, P = 0.04), RAF1 (v-raf-1 murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1; ratio 5.3, P = 0.04), TNFRSF1A (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1A; ratio 4.8, P = 0.05). Expression data were then validated by quantitative PCR and/or Western blot. Indeed, NFKB and NFKBIA expression was higher in GNAS-mutant tumors than in PPNAD samples at messenger and protein levels (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1, B–D). EPAC-2 and RAB13, which are activated by a cAMP-dependent but PKA-independent mechanism, were highly expressed in adrenal tumors with GNAS mutations at the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 1, B and C) but not in those with PRKAR1A mutations.

Fig. 1.

A, Functional analysis of whole-genome transcriptome profiling of PPNAD and adrenal masses harboring the GNAS mutation. The array functional analysis was performed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 2008, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp). B, Expression of NFKB1, RAB13, EPAC2 and BMP4 in the GNAS mutant lesions compared with PPNAD by quantitative PCR. C, NFKB1, IKBa, and RAB13 proteins by Western blot. D, NFKB1 and IKBa staining was stronger in AIMAH/MMAD with the R201H GNAS mutation than in a PRKAR1A-mutant PPNAD. IMAH, ACTH-independent macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

We also analyzed the overlap between the PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions. FATE1, FOSB, CXCR4, NOV, PDE2A, NR4A1, NR5A1, NR0B1, FGF9, and CASP9 were among the genes overexpressed in both groups (Supplemental Table 1). On the other hand, TH, CART, CHCB, RBP7, RGS4, IGFBP4, and IGFBP3 were among the genes underexpressed in both PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions (Supplemental Table 2).

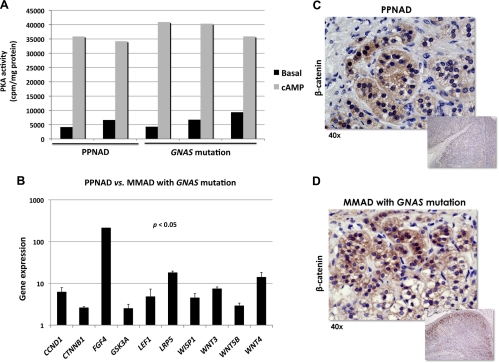

This variability in gene expression was not accompanied by significant differences in PKA activity: the latter was measured in five samples (Fig. 2A). After cAMP exposure, PKA activity was similar in PPNAD and GNAS-mutant tumors (35.046 ± 4.753 vs. 39.062 ± 2.757 cpm/mg protein).

Fig. 2.

A, Basal and cAMP-stimulated PKA activity in PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions. B, A qRT-PCR array including 84 genes involved in Wnt signaling demonstrated that key oncogenes were overexpressed in PRKAR1A- vs. GNAS-mutant lesions. C and D, β-Catenin staining was strong in both PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions, but interestingly only in nodules in the former.

Cancer pathways

A qRT-PCR array carrying 84 genes of the Wnt signaling pathway was tested in both GNAS- and PRKAR1A-mutant samples. CCND1, CTNNB1, LEF1, LRP5, WISP1, and WNT3 were overexpressed in PRKAR1A-mutant lesions (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemistry for β-catenin per se was strongly positive (nuclear and cytoplasmic) in both the PPNAD and GNAS-mutant lesions (Fig. 2, C and D), but only in nodules in the former.

Apoptosis, cancer, and cell cycle pathways were also studied and compared with normal adrenal pools. Among 84 genes included in the apoptosis array plate, IGF1R, CASP3, CARD6, BAG1, and ABL1 were significantly overexpressed in PRKAR1A-mutant samples (Supplemental Table 3). In addition, expression of the oncogenes FGFR2 and RAF1 was significantly higher in PPNAD (Supplemental Table 4). Cell cycle genes were also found to be overexpressed in PPNAD (Supplemental Table 5), including CDK6, CDK8, CCNC, and CCNT1.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the expression signature of PPNAD caused by PRKAR1A-truncating mutations and adrenal masses harboring somatic GNAS mutations. In other words, we studied two adrenal lesions that are both caused by genetic defects, leading to increased cAMP/PKA signaling. The MAPK and p53 signaling pathways were enriched in both the PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions, but a significant enrichment with the ECM receptor interaction and focal adhesion pathways characterized only the latter. Indeed, proteins involved with ECM receptor interaction and adhesion, such as integrins and their ligands, are induced by EPAC2 (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP; cAMP-GEFII; RapGEF4) activation through a cAMP-dependent but PKA-independent mechanism (19). Our transcriptome analysis revealed that EPAC2 is overexpressed in MMAD with a GNAS mutation.

NFKB was overexpressed in GNAS-mutant lesions. Lee et al. (20) showed that activation of NFKB, MAPK, and p300 are essential for IL-1B-induced cytosolic phospholipase A2 expression and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) secretion. We recently demonstrated that increased PKA led to inflammation-independent activation of caspase-1 via overexpression of the protooncogene (and early osteoblast factor) Ets-1 (21). Caspase-1 activation promotes IL-1B production, which is a potent stimulator of cyclooxygenase-2 and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, the main enzymes to PGE2 elevation. High PGE2 levels in cells with defective PKA regulation increased cAMP levels and in turn activated Wnt signaling, like in other states of inappropriate PKA activity (21).

The findings of this study have important implications for therapeutics because the two pathways (NFKB and PKA) can now be targeted interchangeably (or, maybe, simultaneously) in adrenal lesions associated with either GNAS mutation or PKA defects. Interestingly, IL-1B antagonists and caspase-1 inhibitors have been proposed as useful drugs to control the bone manifestations of patients with PKA defects or McCune-Albright syndrome (21).

This study shows the overexpression of key genes that are part of Wnt signaling and other cancer pathways in PPNAD; β-catenin expression was strong in both PRKAR1A- and GNAS-mutant lesions, although in the former only within the nodules. Previous expression studies in PPNAD and AIMAH/MMAD demonstrated the overexpression of genes involved in Wnt signaling activation (11, 12, 22). Somatic mutations of the CTNNB1 gene have been found in adrenal tumors from patients with PPNAD and CNC caused by germline PRKAR1A-inactivating mutations (23, 24). Recently a microRNA profile analysis showed that cAMP and/or PKA via microRNA regulation affects the Wnt signaling pathway in both PPNAD (25) and AIMAH/MMAD (26). miR-449 was one of the highest down-regulated microRNA in PPNAD and is predicted to regulate WISP2, a gene that we had also identified as overexpressed in the adrenal glands of patients with AIMAH/MMAD and food-dependent CS (12). The present study confirms that Wnt signaling is an important mediator of adrenal tumors related to PRKAR1A mutations, probably more so than those due to GNAS mutations.

In conclusion, this report demonstrates that not all increased cAMP/PKA signaling is the same with regard to adrenocortical tumor formation. Clearly the role of non-PKA-dependent functions of cAMP in the adrenal cortex has not been adequately investigated. These data also show that cAMP signaling inhibitors will have to be titrated for non-PKA-dependent effects if they are ever to be used as molecularly designed therapies for subclinical CS in the context of bilateral adrenal hyperplasias.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Intramural Project Grant Z01-HD-000642-04 from the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to C.A.S.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AIMAH

- ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia

- CNC

- Carney complex

- CS

- Cushing syndrome

- DAVID

- Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- IKBa

- inhibitory-κB

- MMAD

- massive macronodular adrenocortical disease

- NFKB

- nuclear factor-κB

- PDE

- phosphodiesterase

- PGE2

- prostaglandin E2

- PKA

- protein kinase A

- PPNAD

- primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real-time PCR

- RAB-13

- renin-angiotensin system oncogene family 13

- WGEP

- whole-genome expression profile.

References

- 1. Bourdeau I, Matyakhina L, Stergiopoulos SG, Sandrini F, Boikos S, Stratakis CA. 2006. 17q22–24 chromosomal losses and alterations of protein kinase a subunit expression and activity in adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:3626–3632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bimpaki EI, Nesterova M, Stratakis CA. 2009. Abnormalities of cAMP signaling are present in adrenocortical lesions associated with ACTH-independent Cushing syndrome despite the absence of mutations in known genes. Eur J Endocrinol 161:153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Almeida MQ, Stratakis CA. 2011. How does cAMP/protein kinase A signaling lead to tumors in the adrenal cortex and other tissues? Mol Cell Endocrinol 336:162–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bertherat J, Horvath A, Groussin L, Grabar S, Boikos S, Cazabat L, Libe R, René-Corail F, Stergiopoulos S, Bourdeau I, Bei T, Clauser E, Calender A, Kirschner LS, Bertagna X, Carney JA, Stratakis CA. 2009. Mutations in regulatory subunit type 1A of cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase (PRKAR1A): phenotype analysis in 353 patients and 80 different genotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2085–2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horvath A, Boikos S, Giatzakis C, Robinson-White A, Groussin L, Griffin KJ, Stein E, Levine E, Delimpasi G, Hsiao HP, Keil M, Heyerdahl S, Matyakhina L, Libé R, Fratticci A, Kirschner LS, Cramer K, Gaillard RC, Bertagna X, Carney JA, Bertherat J, Bossis I, Stratakis CA. 2006. A genome-wide scan identifies mutations in the gene encoding phosphodiesterase 11A4 (PDE11A) in individuals with adrenocortical hyperplasia. Nat Genet 38:794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horvath A, Giatzakis C, Robinson-White A, Boikos S, Levine E, Griffin K, Stein E, Kamvissi V, Soni P, Bossis I, de Herder W, Carney JA, Bertherat J, Gregersen PK, Remmers EF, Stratakis CA. 2006. Adrenal hyperplasia and adenomas are associated with inhibition of phosphodiesterase 11A in carriers of PDE11A sequence variants that are frequent in the population. Cancer Res 66:11571–11575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Horvath A, Mericq V, Stratakis CA. 2008. Mutation in PDE8B, a cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase in adrenal hyperplasia. N Engl J Med 358:750–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Libé R, Fratticci A, Coste J, Tissier F, Horvath A, Ragazzon B, Rene-Corail F, Groussin L, Bertagna X, Raffin-Sanson ML, Stratakis CA, Bertherat J. 2008. Phosphodiesterase 11A (PDE11A) and genetic predisposition to adrenocortical tumors. Clin Cancer Res 14:4016–4024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fragoso MC, Domenice S, Latronico AC, Martin RM, Pereira MA, Zerbini MC, Lucon AM, Mendonca BB. 2003. Cushing's syndrome secondary to adrenocorticotropin-independent macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia due to activating mutations of GNAS1 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:2147–2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bertherat J, Groussin L, Sandrini F, Matyakhina L, Bei T, Stergiopoulos S, Papageorgiou T, Bourdeau I, Kirschner LS, Vincent-Dejean C, Perlemoine K, Gicquel C, Bertagna X, Stratakis CA. 2003. Molecular and functional analysis of PRKAR1A and its locus (17q22–24) in sporadic adrenocortical tumors: 17q losses, somatic mutations, and protein kinase A expression and activity. Cancer Res 63:5308–5319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horvath A, Mathyakina L, Vong Q, Baxendale V, Pang AL, Chan WY, Stratakis CA. 2006. Serial analysis of gene expression in adrenocortical hyperplasia caused by a germline PRKAR1A mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:584–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bourdeau I, Antonini SR, Lacroix A, Kirschner LS, Matyakhina L, Lorang D, Libutti SK, Stratakis CA. 2004. Gene array analysis of macronodular adrenal hyperplasia confirms clinical heterogeneity and identifies several candidate genes as molecular mediators. Oncogene 23:1575–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Almeida MQ, Muchow M, Boikos S, Bauer AJ, Griffin KJ, Tsang KM, Cheadle C, Watkins T, Wen F, Starost MF, Bossis I, Nesterova M, Stratakis CA. 2010. Mouse Prkar1a haploinsufficiency leads to an increase in tumors in the Trp53+/− or Rb1+/− backgrounds and chemically induced skin papillomas by dysregulation of the cell cycle and Wnt signaling. Hum Mol Genet 19:1387–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheadle C, Vawter MP, Freed WJ, Becker KG. 2003. Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J Mol Diagn 5:73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Kir J, Liu D, Bryant D, Guo Y, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. 2007. DAVID Bioinformatics Resources: expanded annotation database and novel algorithms to better extract biology from large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res 35:W169–W175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. 2009. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nat Protoc 4:44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2[-ΔΔC(T)] Method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rohlff C, Clair T, Cho-Chung YS. 1993. 8-Cl-cAMP induces truncation and down-regulation of the RIα subunit and up-regulation of the RIIβ subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase leading to type II holoenzyme-dependent growth inhibition and differentiation of HL-60 leukemia cells. J Biol Chem 268:5774–5782 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gloerich M, Bos JL. 2010. Epac: defining a new mechanism for cAMP action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 50:355–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee CW, Lee IT, Lin CC, Lee HC, Lin WN, Yang CM. 2010. Activation and induction of cytosolic phospholipase A2 by IL-1β in human tracheal smooth muscle cells: role of MAPKs/p300 and NF-κB. J Cell Biochem 109:1045–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Almeida MQ, Tsang KM, Cheadle C, Watkins T, Grivel JC, Nesterova M, Goldbach-Mansky R, Stratakis CA. 2011. Protein kinase A regulates caspase-1 via Ets-1 in bone stromal cell-derived lesions: a link between cyclic AMP and pro-inflammatory pathways in osteoblast progenitors. Hum Mol Genet 20:165–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Almeida MQ, Harran M, Bimpaki EI, Hsiao HP, Horvath A, Cheadle C, Watkins T, Nesterova M, Stratakis CA. 2011. Integrated genomic analysis of nodular tissue in macronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia: progression of tumorigenesis in a disorder associated with multiple benign lesions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:E728–E738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tadjine M, Lampron A, Ouadi L, Horvath A, Stratakis CA, Bourdeau I. 2008. Detection of somatic beta-catenin mutations in primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 69:367–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gaujoux S, Tissier F, Groussin L, Libé R, Ragazzon B, Launay P, Audebourg A, Dousset B, Bertagna X, Bertherat J. 2008. Wnt/β-catenin and 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate/protein kinase A signaling pathways alterations and somatic β-catenin gene mutations in the progression of adrenocortical tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4135–4140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iliopoulos D, Bimpaki EI, Nesterova M, Stratakis CA. 2009. MicroRNA signature of primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease: clinical correlations and regulation of Wnt signaling. Cancer Res 69:3278–3282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bimpaki EI, Iliopoulos D, Moraitis A, Stratakis CA. 2010. MicroRNA signature in massive macronodular adrenocortical disease and implications for adrenocortical tumorigenesis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 72:744–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]