Abstract

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is widely used as an index of mean glycemia in diabetes, as a measure of risk for the development of diabetic complications, and as a measure of the quality of diabetes care. In 2010, the American Diabetes Association recommended that HbA1c tests, performed in a laboratory using a method certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program, be used for the diagnosis of diabetes. Although HbA1c has a number of advantages compared to traditional glucose criteria, it has a number of disadvantages. Hemoglobinopathies, thalassemia syndromes, factors that impact red blood cell survival and red blood cell age, uremia, hyperbilirubinemia, and iron deficiency may alter HbA1c test results as a measure of average glycemia. Recently, racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose have also been described. Although the reasons for racial and ethnic differences remain unknown, factors such as differences in red cell survival, extracellular-intracellular glucose balance, and nonglycemic genetic determinants of hemoglobin glycation are being explored as contributors. Until the reasons for these differences are more clearly defined, reliance on HbA1c as the sole, or even preferred, criterion for the diagnosis of diabetes creates the potential for systematic error and misclassification. HbA1c must be used thoughtfully and in combination with traditional glucose criteria when screening for and diagnosing diabetes.

In the late 1960s, hemoglobin A1 was first recognized as a glycated form of hemoglobin that was increased in patients with diabetes (1), and in 1976, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was first proposed as an indicator of both glucose tolerance and glucose regulation in diabetes (2, 3). Since the 1980s, HbA1c has been increasingly accepted as an index of mean glycemia in patients with diabetes, a measure of risk for the development of diabetic complications, and a measure of the quality of diabetes care. The simplistic concept of HbA1c is that erythrocyte life span is constant, erythrocytes are freely permeable to glucose, hemoglobin glycation occurs nonenzymatically at a rate directly proportional to the ambient glucose concentration, and so, HbA1c provides a glycemic history of the previous 120 d.

In 2009, an International Expert Committee convened by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and the International Diabetes Federation recommended that HbA1c be used for the diagnosis of diabetes (4). In 2010, the ADA recommended that a HbA1c of at least 6.5%, performed in a laboratory using a method certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program, be used for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (5). In making this recommendation, the ADA cited disadvantages of the oral glucose tolerance test for the diagnosis of diabetes, including the fact that it is inconvenient, susceptible to modification by short-term lifestyle changes, and subject to large intraindividual biological variation. It also highlighted preanalytic and analytic problems with the glucose assay, including glycolysis that occurs in improperly processed specimens and lack of standardization of glucose assays across laboratories. At the same time, the ADA cited advantages of HbA1c, including its familiarity to clinicians, convenience, preanalytic stability, and assay standardization. The ADA also recognized that HbA1c has a number of limitations for the diagnosis of diabetes. Any factors that shorten red blood cell survival or decrease mean red blood cell age such as hemolytic anemia, recovery from acute blood loss, or erythropoietin therapy will lower HbA1c test results relative to the true level of glycemia. In addition, both structural hemoglobinopathies, mutations that alter the amino acid sequence of globin and thus alter its physiological properties, and the thalassemia syndromes, mutations that impair production or translation of globin mRNA leading to deficient globin biosynthesis, may impact HbA1c as a measure of average glycemia. Advanced liver disease, kidney disease, and iron deficiency have also been reported to impact HbA1c test results. The impact of these factors varies according to the assay method used, and immunoassays, compared with assays employing HPLC, are more likely to be affected. The ADA thus recommended that the decision about which test to use for the diagnosis of diabetes be at the discretion of the health care professional and that glucose criteria be used exclusively in individuals with known interfering conditions.

A less well-recognized but important limitation of HbA1c as a diagnostic test for diabetes relates to the observation that among nondiabetic individuals, less than one third of the variance in HbA1c is explained by glycemia, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and diet (6). This suggests that at or near normal glucose levels, where HbA1c has been recommended for the diagnosis of diabetes, glycemia is a less important determinant of hemoglobin glycation and other factors operate to produce consistent changes in HbA1c. Potential explanations for this variation in hemoglobin glycation at or near normal glucose levels have focused on interindividual variation in red cell turnover (7), differences between the intraerythrocyte and extraerythrocyte environment (8), and genetic variation in hemoglobin glycation (9, 10).

Support for the hypothesis that subclinical variation in red cell turnover might account for interindividual variation in hemoglobin glycation has come from studies involving biotin labeling of red cells. These have suggested that red cell life span heterogeneity in hematologically normal people is sufficient to alter HbA1c by more than 1% (7), which would substantially alter clinical decision-making.

Studies of the glycation gap, a measure of the difference between the measured HbA1c (reflecting the glycation of intracellular hemoglobin) and the HbA1c predicted from the concentration of a glycated extracellular plasma protein (fructosamine or glycated albumin), based upon the population regression of HbA1c on the glycated plasma protein, have indicated frequent discordance between the two measures of glycemia. It is important to exclude proteinuria or other states of abnormal protein metabolism as an explanation for this discordance. How often other unexplained, reproducible, steady-state discordance is attributable to differences between the intracellular and extracellular environment (8), mean red cell age, or modifiers of hemoglobin glycation remains to be determined. Nearly one fourth of patients have measured HbA1c levels more than 1% higher than predicted, and almost one fifth have measured HbA1c levels more than 1% lower than predicted by glycated plasma protein levels under circumstances in which factors impacting plasma protein turnover (such as proteinuria) are not present (11). Similar findings have been reported when HbA1c has been compared with capillary glucose profiles (12). There is a high intraindividual reproducibility of the glycation gap (11, 13), reflecting good correlation between HbA1c and glycated plasma proteins within individuals across a range of glycemic control, and high heritability of the glycation gap in nondiabetic identical twins (69%) (10), suggesting that the glycation gap is genetically determined.

Additional support for the hypothesis that there are genetic determinants of hemoglobin glycation independent of glycemia comes from a collaborative genome-wide association study that identified common variants at 10 genomic loci that influence HbA1c levels (14). Three of the variants appear to operate via glycemic mechanisms, but seven polymorphisms appear to operate via their influence on red blood cell membrane function and iron metabolism (14). The observation that polymorphisms impacting red blood cell membrane function are determinants of hemoglobin glycation supports the hypothesis that there may be differences between the intracellular and extracellular environments. The finding that polymorphisms influencing erythrocyte iron metabolism are associated with hemoglobin glycation is also consistent with the clinical observation that iron deficiency is associated with higher HbA1c levels (15).

Recently, racial and ethnic variations in HbA1c have been reported to impact the potential utility of HbA1c as a diagnostic test for diabetes. Racial and ethnic differences in HbA1c have been recognized for many years but have generally been attributed to differences in access to medical care or quality of care (16). Boltri et al. (17) analyzed data from the 1999–2000 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and described HbA1c in persons with undiagnosed and diagnosed diabetes by race/ethnicity. Mean HbA1c was 7.6% in Whites, 8.1% in Blacks, and 8.2% in Hispanics (17). Saydah et al. (18) also analyzed data from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey by race/ethnicity but adjusted for potential confounders including socioeconomic status, health care access, obesity, and diabetes treatment. After multivariate adjustment, differences in glycemic control by race/ethnicity persisted. Adams et al. (19) further explored the contribution of medication adherence to Black-White differences in HbA1c among type 2 diabetic patients in a large multispecialty group practice. At initiation of oral antihyperglycemic therapy, Whites had an average HbA1c of 8.9% compared with 9.8% in Blacks. Blacks had lower average medication adherence during the first year of therapy (72 vs. 78%), but adjustment for adherence did not eliminate the Black-White difference in HbA1c. Subsequently, Heisler et al. (20) used data from the Health and Retirement Study to explore the mechanisms for racial and ethnic differences in HbA1c. In respondents taking medications, mean HbA1c was 7.2% in Whites, 8.1% in Blacks, and 8.1% in Latinos. Sociodemographic and clinical factors, access to and quality of diabetes health care, and self-management attitudes and behaviors accounted for only 14% of the higher HbA1c levels in Black respondents and 19% in Latinos. Fully adjusted models were only able to explain approximately one fifth of the racial and ethnic differences in HbA1c. Thus, although adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, access to care, quality of care, and self-management behaviors attenuate racial and ethnic differences in HbA1c, it does not fully explain those differences.

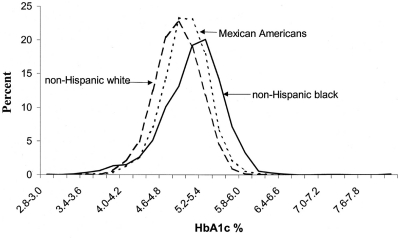

Further support for the hypothesis that there are racial and ethnic differences in hemoglobin glycation comes from studies of nondiabetic children. Saaddine et al. (21) analyzed HbA1c data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-3) for participants aged 5 to 24 yr who had not been treated for diabetes. They demonstrated different population distributions of HbA1c. After adjusting for age, sex, education, overweight, and fasting glucose level, healthy, non-Hispanic Black youths had consistently higher HbA1c levels than non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanic-Americans (Fig. 1). In a subsequent analysis of predictors of HbA1c in nondiabetic children 4 to 17 yr of age, Eldeirawi and Lipton (22) found that African-Americans and Mexican-Americans had higher mean HbA1c levels than non-Hispanic Whites after controlling for age, sex, BMI, maternal BMI, and poverty-income ratio (5.17 vs. 5.03 vs. 4.97%, respectively).

Fig. 1.

HbA1c distribution by ethnicity in U.S. children and young adults ages 5–24 yr (NHANES-3, 1988–1994) (Ref. 21).

Based upon these findings, we sought to determine whether, after adjustment for differences in glycemia, there were racial/ethnic differences in HbA1c among patients with impaired glucose tolerance, recent onset type 2 diabetes, and long-standing type 2 diabetes. In a study of nearly 4000 individuals eligible to participate in the Diabetes Prevention Program [age ≥ 25 yr, BMI ≥ 24 kg/m2, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 95–125 mg/dl, and 2-h post glucose load glucose of 140–199 mg/dl], we found that both before and after adjusting for age, sex, education, marital status, adiposity, blood pressure, fasting and postload glucose, glucose area under the curve, β-cell function, insulin resistance, and hematocrit, HbA1c levels were significantly higher in Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Asian participants compared with Whites (P < 0.0001) (23). Adjusted HbA1c was 5.8% in Whites, 6.2% in Blacks, 5.9% in Hispanics, 6.1% in American Indians, and 6.0% in Asians.

In another study of the ADOPT (A Diabetes Outcome Progression Study) cohort, a population of patients 30–75 yr of age with type 2 diabetes diagnosed within 3 yr with FPG between 126 and 180 mg/dl and no previous pharmacological therapy, we compared HbA1c among racial and ethnic groups before and after adjustment for age, sex, and BMI (24). Adjusted HbA1c was 7.3% in Whites, 8.0% in Blacks, and 8.0% in Hispanics, despite lower mean FPG in Whites and higher 30-min post-glucose load glucose excursion in Whites compared with Blacks (P < 0.001).

Finally, in an analysis of patients 30–80 yr of age with type 2 diabetes and HbA1c more than 7% on at least two oral antihyperglycemic agents enrolled in the DURABLE Trial, we compared HbA1c among racial and ethnic groups before and after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, duration of diabetes, diabetes treatment, mean fasting glucose, mean postprandial glucose, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, β-cell function, and insulin resistance (25). Compared with Whites, mean HbA1c levels were 0.37% higher in Blacks, 0.27% higher in Hispanics, and 0.33% higher in Asians (all P < 0.001) (25). Thus, in patients with glucose intolerance, recent-onset type 2 diabetes, and long-standing type 2 diabetes, racial/ethnic minority groups had significantly higher HbA1c levels than Whites after adjusting for fasting and post-glucose load glucose levels, 1,5-anhydroglucitol, and other factors associated with glycemia.

In an analysis of data from the Screening for Impaired Glucose Tolerance Study (SIGT) and the NHANES-3, Ziemer et al. (26) confirmed and extended these findings. They assessed Black-White differences in HbA1c in subjects with normal glucose tolerance, prediabetes, and diabetes after adjusting for age, sex, education, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting and 2-h plasma glucose, and hemoglobin. They observed that Blacks had consistently higher HbA1c levels than Whites across the continuum of glycemia (Table 1).

Table 1.

Glucose-independent, Black-White differences in HbA1c levels in the Screening for Impaired Glucose Tolerance (SIGT) study and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 3 (NHANES-3)

| Study | Black-White difference in HbA1ca |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| NGT | Prediabetes | Diabetes | |

| SIGT | +0.13 | +0.26 | +0.47 |

| NHANES-3 | +0.21 | +0.30 | +0.47 |

NGT, Normal glucose tolerance. Data are from Ref. 26.

Adjusted for fasting and 2-h glucose, age, sex, education, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and hemoglobin.

Selvin et al. (27) subsequently performed a cross-sectional analysis of community-based data to assess racial differences in glycemic markers. Unlike previous studies, the only direct measure of glucose available was the fasting glucose level. As in previous studies, they found that Blacks with and without diabetes had significantly higher HbA1c levels than Whites both before and after adjustment for covariates and fasting glucose concentrations. Unlike previous studies, however, they demonstrated that Blacks had significantly higher glycated albumin and fructosamine levels than Whites and significantly lower serum 1,5-anhyroglucitol levels than Whites. This suggests that higher HbA1c levels among Blacks could reflect higher concentrations of nonfasting glycemia (which they were unable to assess directly). Although intriguing, the results of this study are not consistent with the results of other studies that have assessed both fasting and post-glucose load glucose levels (23–26) and 1,5-anhyroglucitol (25).

To date, racial and ethnic differences in red blood cell survival, the intracellular and extracellular environment, and genetic determinants of hemoglobin glycation have not been assessed. Such studies are needed. In addition, the important question that must be addressed is whether the observed racial and ethnic differences in hemoglobin glycation reflect a greater predisposition to diabetic complications. Selvin et al. (28) analyzed data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study and found that despite significantly higher mean HbA1c values in nondiabetic Blacks than nondiabetic Whites (5.8 vs. 5.4%; P < 0.001), there was no significant interaction between race, HbA1c, and coronary heart disease, ischemic stroke, or death from any cause (P > 0.08 for all interactions). Whether race modifies the association between HbA1c and microvascular and neuropathic outcomes remains unknown.

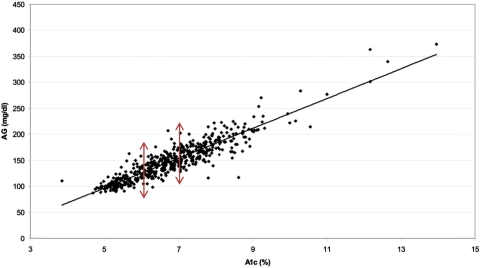

Taken together, available data suggest that hemoglobin glycation has important determinants other than glycemia. The relationship between mean blood glucose and HbA1c may not be the same in all people. Indeed, the published regression line from the “A1c-Derived Average Glucose” (ADAG) Study demonstrated a wide range of average glucose levels for individuals with the same HbA1c levels (represented by a point on Fig. 2) (29). An HbA1c value of 6.0% corresponds to an estimated average glucose of 100–152 mg/dl, and an HbA1c value of 7.0% corresponds to an estimated average glucose of 123–185 mg/dl (95% confidence intervals) (29).

Fig. 2.

The ADAG Study: Average glucose (AG; over 3 months) vs. HbA1c (study end) (Ref. 29).

In the ADAG Study, the frequency of glucose assessments and the time frame of the measurements (approximately 2700 glucose values obtained by each subject over 3 months) reduced measurement variation and sampling time variation, leaving true biological variation as the most likely explanation for the wide confidence intervals in A1c-derived average glucose levels. It is also instructive to note that the range of 95% confidence intervals for A1c-derived average glucose levels was largest (when expressed as a percentage of the A1c-derived average glucose level) at the lowest HbA1c levels and decreased with increasing HbA1c levels. This is consistent with the observation that less of the variation in A1c-derived average glucose is explained by glycemia at near-normal HbA1c levels (6).

Although the ADAG Study was underpowered to assess racial differences in A1c-derived average glucose due to problems related to sample storage and shipment, there was a suggestion (P = 0.07) that the regression line relating HbA1c to average glucose for African-Americans had a different slope and intercept than the regression line for Whites, such that for a given value of HbA1c, African-Americans had lower mean glucose levels (29). Thus, it may not be possible to predict true average glucose with a high degree of accuracy in a given person based on his or her HbA1c result alone, and there may be systematic differences in the relationship between HbA1c and average glucose across racial and ethnic groups.

All of these issues are relevant when considering the use of HbA1c as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes. When used for diabetes management, HbA1c levels are interpreted in light of glucose-monitoring results, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the patient's actual glucose control. When HbA1c measurements are performed in the same individual with diabetes, that person serves as his or her own control, and HbA1c provides a calibrated measure of glycemic control over time. When used as a diagnostic test for diabetes, in the absence of corroborative blood glucose or glycated plasma protein (fructosamine or albumin) readings and without concurrent hemoglobinopathy or thalassemia screening, testing for hemolytic anemia and iron deficiency, and testing for liver and renal impairment, the HbA1c result may be misleading. Similarly, failure to recognize nonglycemic hereditary components to hemoglobin glycation and neglecting potential racial and ethnic differences in hemoglobin glycation may lead to misclassification. Concordance between HbA1c and glucose or glycated plasma protein levels reduces the likelihood of misclassification by providing a confirmatory test.

HbA1c has a role in the diagnosis of diabetes when laboratory-based HbA1c assays are available, when there are no known patient factors that preclude the interpretation of HbA1c, when glucose testing is not convenient, and when glycemia is not changing rapidly and type 1 diabetes is not suspected. However, glucose testing should be used if it is convenient, if laboratory-based HbA1c is not available, if there are known or suspected patient factors that preclude interpretation of HbA1c, or if type 1 diabetes is suspected. Because unknown factors might also impact hemoglobin glycation, reliance on HbA1c as the sole or even the preferred diagnostic criterion may lead to persistent systematic misclassification, especially in the setting of clinically unrecognized hemoglobinopathy or thalassemia syndromes, hemolytic anemia, iron deficiency, liver or renal impairment, or intrinsic factors impacting hemoglobin glycation, including subclinical variation in red cell turnover, differences between the extracellular and intraerythrocyte environment, and genetic variation in hemoglobin glycation.

A “rule-in, rule-out” approach to HbA1c testing may be most appropriate for the diagnosis of diabetes (30). With this approach, glucose criteria are used to confirm or exclude diabetes in the context of intermediate levels of HbA1c. Using HbA1c thresholds lower and higher than suggested by the ADA for ruling out or ruling in diabetes permits one to triage patients for further glucose testing. For example, by using a “rule-out” HbA1c cutoff of 5.5% or less and a “rule-in” threshold of 7% or more, one eliminates approximately three fourths of the population from further investigation. In the remaining one fourth of patients with intermediate levels of HbA1c between 5.6 and 6.9%, glucose testing may be used to confirm or refute diabetes. Indeed, either screening with HbA1c and confirming with plasma glucose or screening with plasma glucose and confirming with HbA1c may be the most robust approach to diagnosing diabetes (31). Under this scenario, lower thresholds for FPG (≥100 mg/dl) and HbA1c (≥5.6%) would be used to define positive screening tests, and if screening tests were positive but less than the diagnostic threshold (FPG ≥126 mg/dl, or HbA1c ≥6.5%) additional testing (i.e. FPG, HbA1c, or 2-h plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dl) would be required for a diagnosis of diabetes.

Reliance on HbA1c as the sole, or even preferred, criterion for diabetes diagnosis creates the potential for systematic error due to “known confounders” that are clinically unrecognized (such as hemolytic anemia) and “unknown confounders” that we are just beginning to appreciate (such as interindividual differences in red cell survival, extracellular-intracellular glucose balance, and nonglycemic genetic determinants of hemoglobin glycation). HbA1c criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes must be used thoughtfully and in combination with traditional glucose criteria. Doing the same thing over and over again, such as testing HbA1c, and expecting different results is the very definition of insanity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center, and funded by Grant DK020572 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service [R01 DK63088 and UL1 RR026314 (National Center for Research Resources)], the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (I01 CX000121-01), and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: W.H.H. has nothing to declare. R.M.C. has served on a Roche Advisory Board.

Footnotes

- ADA

- American Diabetes Association

- ADAG Study

- A1c-Derived Average Glucose Study

- BMI

- body mass index

- FPG

- fasting plasma glucose

- HbA1c

- hemoglobin A1c.

References

- 1. Rahbar S. 1968. An abnormal hemoglobin in red cells of diabetics. Clin Chim Acta 22:296–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koenig RJ, Peterson CM, Kilo C, Cerami A, Williamson JR. 1976. Hemoglobin A1c as an indicator of the degree of glucose intolerance in diabetes. Diabetes 25:230–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koenig RJ, Peterson CM, Jones RL, Saudek C, Lehrman M, Cerami A. 1976. Correlation of glucose regulation and hemoglobin A1c in diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 295:417–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. International Expert Committee 2009. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1c assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:1327–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Diabetes Association 2010. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1):S11–S61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yudkin JS, Forrest RD, Jackson CA, Ryle AJ, Davie S, Gould BJ. 1990. Unexplained variability of glycated haemoglobin in non-diabetic subjects not related to glycaemia. Diabetologia 33:208–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen RM, Franco RS, Khera PK, Smith EP, Lindsell CJ, Ciraolo PJ, Palascak MB, Joiner CH. 2008. Red cell life span heterogeneity in hematologically normal people is sufficient to alter HbA1c. Blood 112:4284–4291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khera PK, Joiner CH, Carruthers A, Lindsell CJ, Smith EP, Franco RS, Holmes YR, Cohen RM. 2008. Evidence for inter-individual variation in the glucose gradient across the human RBC membrane and its relationship to Hb1c. Diabetes 57:2445–2452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snieder H, Sawtell PA, Ross L, Walker J, Spector TD, Leslie RD. 2001. HbA(1c) levels are genetically determined even in type 1 diabetes: evidence from healthy and diabetic twins. Diabetes 50:2858–2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen RM, Snieder H, Lindsell CJ, Beyan H, Hawa MI, Blinko S, Edwards R, Spector TD, Leslie RD. 2006. Evidence for independent heritability of the glycation gap (glycosylation gap) fraction of HbA1c in nondiabetic twins. Diabetes Care 29:1739–1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen RM, Holmes YR, Chenier TC, Joiner CH. 2003. Discordance between HbA1c and fructosamine: evidence for a glycosylation gap and its relation to diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Care 26:163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCarter RJ, Hempe JM, Gomez R, Chalew SA. 2004. Biological variation in HbA1c predicts risk of retinopathy and nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:1259–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nayak AU, Holland MR, Macdonald DR, Nevill A, Singh BM. 2011. Evidence for consistency of the glycation gap in diabetes. Diabetes Care 34:1712–1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Soranzo N, Sanna S, Wheeler E, Gieger C, Radke D, Dupuis J, Bouatia-Naji N, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, Stolerman E, Sandhu MS, Heeney MM, Devaney JM, Reilly MP, Ricketts SL, Stewart AF, Voight BF, Willenborg C, Wright B, Altshuler D, Arking D, Balkau B, Barnes D, Boerwinkle E, Böhm B, Bonnefond A, Bonnycastle LL, Boomsma DI, Bornstein SR, Böttcher Y, Bumpstead S, Burnett-Miller MS, Campbell H, Cao A, Chambers J, Clark R, Collins FS, Coresh J, de Geus EJ, Dei M, et al. 2010. Common variants at 10 genomic loci influence hemoglobin A1 (C) levels via glycemic and nonglycemic pathways. Diabetes 59:3229–3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim C, Bullard KM, Herman WH, Beckles GL. 2010. Association between iron deficiency and A1c levels among adults without diabetes in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2006. Diabetes Care 33:780–785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirk JK, Bell RA, Bertoni AG, Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Goff DC, Jr, Narayan KM. 2005. Ethnic disparities: control of glycemia, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol among US adults with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother 39:1489–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boltri JM, Okosun IS, Davis-Smith M, Vogel RL. 2005. Hemoglobin A1c levels in diagnosed and undiagnosed Black, Hispanic, and White persons with diabetes: results from NHANES 1999–2000. Ethn Dis 15:562–567 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saydah S, Cowie C, Eberhardt MS, De Rekeneire N, Narayan KMV. 2007. Race and ethnic differences in glycemic control among adults with diagnosed diabetes in the United States. Ethn Dis 17:529–535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adams AS, Trinacty CM, Zhang F, Kleinman K, Grant RW, Meigs JB, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D. 2008. Medication adherence and racial differences in HbA1c control. Diabetes Care 31:916–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, Langa KM, Blaum C, Weir D. 2007. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the Health and Retirement Study. Arch Intern Med 167:1853–1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saaddine JB, Fagot-Campagna A, Rolka D, Narayan KM, Geiss L, Eberhardt M, Flegal KM. 2002. Distribution of HbA1c levels for children and young adults in the U.S. Diabetes Care 25:1326–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eldeirawi K, Lipton RB. 2003. Predictors of hemoglobin A1c in a national sample of nondiabetic children. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Epidemiol 157:624–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herman WH, Ma Y, Uwaifo G, Haffner S, Kahn SE, Horton ES, Lachin JM, Montez MG, Brenneman T, Barrett-Connor E, for the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group 2007. Differences in A1c by race and ethnicity among patients with impaired glucose tolerance in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 30:2453–2457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Viberti G, Lachin J, Holman R, Zinman B, Haffner S, Kravitz B, Heise MA, Jones NP, O'Neill MC, Freed MI, Kahn SE, Herman WH. for ADOPT Study Group 2006. A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial (ADOPT): baseline characteristics of type 2 diabetic patients in North America and Europe. Diabet Med 23:1289–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herman WH, Dungan KM, Wolffenbuttel BH, Buse JB, Fahrbach JL, Jiang H, Martin S. 2009. Racial and ethnic differences in mean plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and 1.5-anhydroglucitol in over 2,000 patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:1689–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Weintraub WS, Vaccarino V, Rhee MK, Twombly JG, Narayan KM, Koch DD, Phillips LS. 2010. Glucose-independent, black-white differences in hemoglobin A1c levels: a cross-sectional analysis of 2 studies. Ann Intern Med 152:770–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Selvin E, Steffes MW, Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Coresh J, Brancati FL. 2011. Racial differences in glycemic markers: a cross-sectional analysis of community-based data. Ann Intern Med 154:303–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Selvin E, Steffes MW, Zhu H, Matsushita K, Wagenknecht L, Pankow J, Coresh J, Brancati FL. 2010. Glycated hemoglobin, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk in nondiabetic adults. N Engl J Med 362:800–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nathan DM, Kuenen J, Borg R, Zheng H, Schoenfeld D, Heine RJ, for the A1c-Derived Average Glucose (ADAG) Study Group 2008. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care 31:1473–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kilpatrick ES, Winocour PH, on behalf of the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) 2010. ABCD position statement on haemoglobin A1c for the diagnosis of diabetes. Pract Diab Int 27:306–310 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Saudek CD, Herman WH, Sacks DB, Bergenstal RM, Edelman D, Davidson MB. 2008. A new look at screening and diagnosing diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2447–2453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]