Abstract

Many neurological and psychiatric disorders are treated with dopamine modulators. Studies in mice may reveal genetic factors underlying those disorders or responsiveness to various treatments, and species and strain differences both complicate the use of mice and provide valuable tools. We evaluated psychomotor effects of the dopamine D1-like agonist R-6-Br-APB and the dopamine D2-like agonist quinelorane using a locomotor activity procedure in 15 mouse strains (inbred 129S1/SvImJ, 129S6/SvEvTac, 129X1/SvJ A/J, BALB/cByJ, BALB/cJ, C3H/HeJ, C57BL/6J, CAST/EiJ, DBA/2J, FVB/NJ, SJL/J, SPRET/EiJ, outbred Swiss Webster and CD-1) and Sprague Dawley rats, using groups of both females and males. Both D1 and D2 stimulation produced hyperactivity in the rats, and surprisingly, only two mouse strains were similar in that regard (C3H/HeJ, SPRET/EiJ). In contrast, the majority of mouse strains exhibited hyperactivity only with D1 stimulation, whereas D2 stimulation had no effect or decreased activity. BALB substrains, A/J and FVB/NJ mice showed only decreased activity following either D1 or D2 stimulation. CAST/EiJ mice exhibited hyperactivity exclusively with D2 stimulation. Sex differences were observed but no systematic trend emerged: For example, of the five strains in which a main factor of sex was identified for the stimulant effects of the D1 agonist, responsiveness was greatest in females in three of those strains and in males in two of those strains. These results should aid in the selection of mouse strains for future studies in which D1 or D2 responsiveness is a necessary consideration in the experimental design.

Keywords: quinelorane, R-6-Br-APB, mouse strains, locomotor activity, direct dopamine agonists

INTRODUCTION

Dopamine systems play central roles in many functions, including goal-directed movement, reward, learning, sexual functions, cardiovascular homeostasis, and endocrine regulation (for review see Iversen & Iversen, 2007; Jackson & Westlind-Danielsson, 1994). Medications used to treat many neurological and psychiatric disorders (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, attention deficit disorders, Tourette’s syndrome) target dopamine receptors either indirectly (e.g., l-dopa, amphetamine, methylphenidate, modafinil, bupropion) or directly (e.g., pramipexole and most antipsychotic agents). Dopamine systems are also critically involved in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse and in addictions, not only to drugs, but also behaviors such as gambling (Bergman, Kamien, & Spealman, 1990; Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., in press; Roberts, Koob, Klonoff & Fibiger, 1980; Thomsen, Hall, Uhl & Caine, 2009; van Eimeren et al., 2009). Genetic engineering strategies such as null mutations (knockout), under-expression (knockdown), or targeted amino acid modifications (transgenic, knock-in) of genes provide powerful tools that may help shed light on genetic factors underlying the pathophysiology of human disorders and variation in responsiveness to specific treatments. Currently, those tools are predominantly available in the mouse species. Previous studies indicated species and strain differences in effects of dopamine agonists, complicating the use of mice for such research but also providing opportunities to “dissect” the genetic background for those strain or species differences (e.g., using recombinant inbred strains). Specifically, hallmark effects of dopamine D2-like (D2/D3/D4) agonists in rats, such as stimulation of locomotor activity and suppression of prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the startle reflex, were not replicated in commonly used mouse strains such as C57BL/6J, DBA/2J, 129X1/SvJ, or Swiss Webster (Chang, Geyer, Buell, Weber & Swerdlow, 2010; Geter-Douglas, Katz, Alling, Acri & Witkin, 1997; Halberda, Middaugh, Gard & Jackson, 1997; Ralph & Caine, 2005; Ralph-Williams, Lehmann-Masten & Geyer, 2003). On the other hand, we have observed suppression of PPI with D2-like agonists in some less commonly used strains of mice (C3H/HeJ, SPRET/EiJ, CAST/EiJ; Ralph & Caine, 2007).

Here, we extended the above studies to investigate the psychomotor stimulating effects dopamine D1-like and D2-like agonists in a wider selection of inbred mouse strains and outbred stocks. The goals were to 1) evaluate whether the previously observed species difference (lacking psychomotor stimulant effects of D2 agonists in mice relative to rats) would generalize to a wider selection of mouse strains, and 2) identify potential mouse strains in which D1 and D2 agonists show effects similar to rats (i.e., showing stimulant effects of both D1 and D2 agonists). We selected 13 strains of mice, including those prioritized by the Mouse Phenome Database (inbred 129S1/SvImJ, A/J, BALB/cByJ, BALB/cJ, C3H/HeJ, C57BL/6J, CAST/EiJ, DBA/2J, FVB/NJ, SJL/J, SPRET/EiJ). In addition, strains commonly used to generate knockout and other mutant mice are of particular interest, in that the genetic background on which these mutations are expressed can influence the results (Kelly et al., 1998; Phillips, Hen & Crabbe, 1999). In particular, the common use of mixed genetic backgrounds can complicate the attribution of a behavioral phenotype to the targeted mutation (Gerlai, 1996; Lathe, 1996). The C57BL/6J, 129 substrains 129X1/SvJ and 129S6/SvEvTac, and the DBA/2J, are the most widely used strains in the generation of targeted mutations. Finally, we included two commonly used outbred stocks, the Swiss Webster and CD-1 mice, as well as Sprague Dawley rats for comparison. Male and female rodents were included for each strain/stock, mainly as reference data for future studies in which it may be desirable to evaluate both male and female mice.

METHODS

Animals

We characterized male and female inbred 129S1/SvImJ, 129X1/SvJ, A/J, BALB/cByJ, BALB/cJ, C3H/HeJ, C57BL/6J, CAST/EiJ, DBA/2J, FVB/NJ, SJL/J, SPRET/EiJ (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME), and 129S6/SvEvTac mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY). For further strain and species comparisons, we also selected outbred Swiss Webster (Taconic, Germantown, NY) and CD-1/ICR (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) mice, and outbred Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN). For each strain including rats, 8 males and 8 females were tested. There was some attrition, and data were also excluded from subjects that did not tolerate high doses to enable repeated measures analyses, so that the numbers of mice that completed the studies were 16 (8 each sex) with the following exceptions: A/J, R-6-Br-APB: N=12 (6 male + 6 female), quinelorane: N=14 (7+7); BALB/cJ, both drugs: N=15 (8+7); C3H/HeJ and SJL/J, quinelorane: N=15 (8+7); C57BL/6J, both drugs: N=15 (7+8); CAST/EiJ, R-6-Br-APB: N=10 (4+6), quinelorane: N=6 (3+3); CD-1, R-6-Br-APB: N=15 (8+7), quinelorane: N=15 (7+8); DBA/2J, R-6-Br-APB: N=14 (8+6), quinelorane: N=15 (8+7); and SPRET/EiJ, both drugs: N=12 (7+5). Rodents were group housed up to 4 per cage (8.8 X 12.1 X 6.4 inches for mice, 11 X 22 X 8.5 inches for rats) in a climate-controlled animal facility. Each cage was fitted with a filter top through which HEPA-filtered air was introduced (40 changes per hour). Illumination was provided for 12 hr/day (starting at 7:00AM). Food (rodent diet 5001, PMI Feeds, Inc. St. Louis, MO) and water were available ad libitum, except during behavioral testing, and various flavored treats (Bioserve, Frenchtown, NJ) were given weekly for enrichment purposes. Animals were acquired at 6–8 weeks of age (both rats and mice) and were approximately 15–26 weeks of age at the beginning of the experiments reported here (male rats weighed 480–570g, female rats 230–330g). Testing occurred between 8:00 AM and 6:00 PM. Estrous cycles of the female rodents were not monitored.

Vivarium conditions were maintained in accordance with the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health Committee on Laboratory Animal Resources. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The health of the rodents was evaluated by research technicians on a daily basis and was also periodically monitored by consulting veterinarians.

Locomotor Activity Testing

Clear plastic chambers 41.5 × 19 × 28 cm (l × w × h) fitted with filter tops and placed within Photobeam Activity System monitoring frames (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, SA) were used to assess locomotor activity. Seven evenly spaced infrared beams were transmitted across through the cage, 2.7 cm above the floor, for assessment of horizontal activity (repeated and consecutive beam breaks). Eight additional beams were transmitted through the cage lengthwise and measured vertical activity (rearing), at 6.4 cm above the floor for mice, 13.9 cm above the floor for rats. Test chambers were lightly lined with fresh pine shavings before each session, cleaned with water after each session, and cleaned with alkaline detergent at 180 F once weekly and between strain groups. To minimize effects of scents left by previous subjects, half the test chambers were always used for female rodents, and the other chambers for male subjects. An automated equipment (beams) check was performed daily before starting tests, and each chamber was checked to ensure no beams were obstructed before each test. The test sessions were 4 hours long and data were collected in 10-min bins. On each test day, the animals were allowed to acclimate to the test chambers for 1 hr; then removed for injection with vehicle, quinelorane, or R-6-Br-APB, and immediately returned to the test chamber for the remaining 3 hrs of the session. Test sessions were at least 2 days apart. For brevity and ease of presentation, total beam breaks (of both low and elevated sets of beams) were collapsed across time (i.e., sum of the 180 post-injection 10-min bins), and total activity counts for the 3 hours post-injection are presented.

Strains were tested in groups of 2–4 strains concurrently, with separate chambers assigned to each strain. Prior to testing, all animals had three injection-free 4-h habituation sessions, and completed a similar study with eight cocaine tests (3.2, 10, 18, 32 and 56 mg/kg; 3.2, 10 and 32 mg/kg being repeated once; Thomsen & Caine, submitted). Animals were given 1–4 weeks without any injections or testing, then a single session of saline administration, between the cocaine study and the present investigation. The animals were therefore well habituated to the handling procedure by the beginning of this study. Evidence that prior cocaine exposure did not influence the results of this study comes from nearly identical findings reported here to those reported in a previous study of three of the same mouse strains and Sprague-Dawley rats that were cocaine-naïve (Ralph & Caine, 2005).

Drugs

Quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB (Sigma/RBI; St. Louis, MO) were chosen based on both in vitro and in vivo studies suggesting that they are among the most potent and selective compounds commercially available for D2-like and D1-like receptors, respectively, (Bymaster et al., 1986; Durham et al., 1998; Jutkiewicz and Bergman, 2004; Neumeyer et al., 1992). Quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB were dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline and sterile water, respectively. The salt form of each drug was used in dose calculations. Injections were given intraperitoneally (ip) (1 ml/kg for rats, 10 ml/kg for mice). Quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB were tested in counterbalanced order in each strain (i.e., half the subjects received quinelorane first, half R-6-Br-APB first). A within-subjects design was employed, with drug assignment following a Latin-square design, with the exception of the highest dose (5.6 mg/kg), which was tested last. In a few strains higher quinelorane doses were tested, in increasing order, if no effect was observed in the planned range. In some strains R-6-Br-APB caused seizures in a substantial proportion of mice at 3.2 mg/kg, and the 5.6 mg/kg dose was therefore omitted in those strains. Whenever seizures were observed, the subject was “rescued” with diazepam (5 – 10 mg/kg, ip) and data from that session as well as further tests were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

Significance level was set at p<0.05. We had an a priori hypothesis that the strains would differ in baseline locomotor activity levels, and an ANOVA was performed with strain as between-subjects factor, and confirmed this hypothesis. Consequently, the effect of drug treatment was assessed in each strain separately by repeated measures ANOVAs, with sex as between-subjects factor and dose as within-subjects factor. In the few cases where mice did not tolerate high doses of a drug, all data were excluded for these animals, or the highest dose was excluded, as indicated. When there was a significant interaction between sex and drug treatment, data from female and male rodents were also analyzed separately. Distribution of activity by beam break type (i.e. consecutive, sometimes termed “ambulation”, repeated, sometimes termed “fine movement”, and vertical, sometimes termed “rearing”) was analyzed similarly, with break type and dose as within-subjects factors. Significant dose by break type interactions were followed by a repeated measures ANOVA in each beam break type, with drug dose as factor. Significant main effects of dose were followed by paired-samples t-test comparison of drug doses to vehicle, both in the total beam break analysis and in the individual break type analysis.

The mean doses estimated to elicit 50% of the maximal effect (A50 values) were calculated for each mouse by interpolation of the linear portion of the log dose-effect function. In some mice, the lowest dose elicited more than 50% of the maximum effect; in cases of low dose effects <55%, the A50 was estimated by extrapolation, in all other cases the animal was excluded from the A50 calculation. Strains in which 25% or more of the animals had to be excluded, no estimate was made. For each strain, the group mean as well as 95% and 99% confidence limits (95%CL, 99%CL) were calculated. Non-overlapping confidence intervals indicated a significant difference in potency between strains.

For correlations between spontaneous activity levels (total beam breaks during the first 4-h habituation session) and peak effects, the peak (i.e., highest value for increases in activity relative to vehicle, and lowest value for decreases) group means were determined as total beam breaks, %vehicle, and difference score from vehicle. Effects were calculated as %vehicle (drug value / vehicle value × 100) and difference score (drug value – vehicle value) for each animal, then group means were calculated. Peak group means, not averages of individual peaks, were used. Correlations were then evaluated for each measure of peak effect against spontaneous activity by linear regression.

RESULTS

A comparison of total beam breaks after vehicle injection (“baseline”) showed a significant effect of strain [F(1,14)=11.4, p<0.001]. Therefore separate ANOVAs were conducted for each strain for quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB. In all figures, the Sprague Dawley rats are presented in the upper left panel (shaded), and the mouse strains are arranged in the same order as in the cocaine study for ease of comparison (Thomsen & Caine, submitted; arranged by decreasing baseline activity). The effects of quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB on locomotor activity are summarized in Figure 1 and Tables I and II. Total beam breaks per dose of quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB in each sex are shown in Tables III and IV, respectively.

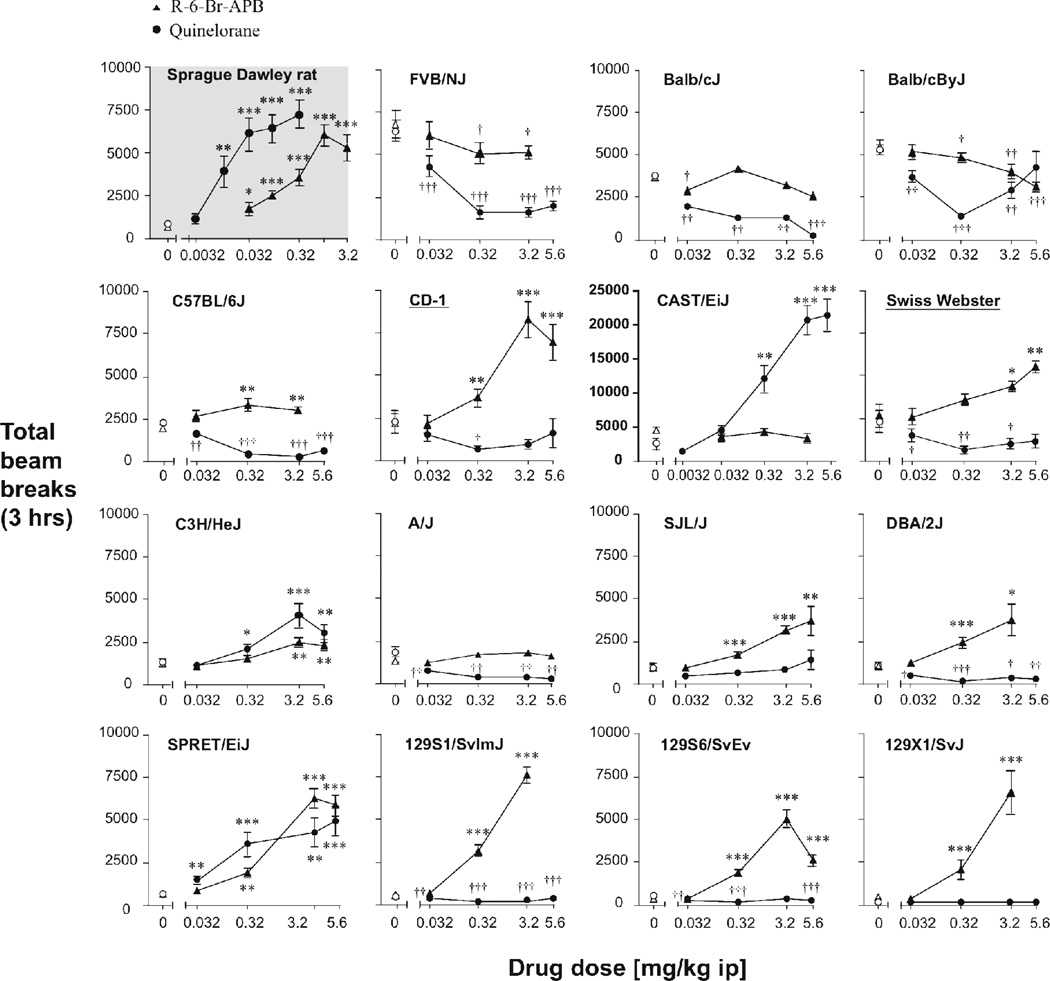

Figure 1.

Locomotor activity stimulation by R-6-Br-APB and quinelorane in Sprague-Dawley rats and 15 strains of mice. Abscissa: drug dose in mg/kg, i.p.; ordinate: total beam breaks per 3-hour session, please note the different axis for the CAST/EiJ strain only. Data are group means, bars represent one SEM. Rats are shown in top left (shaded grey background). Thereafter, mouse strains are ranked from top-left to bottom-right by decreasing activity levels after the initial saline injection (not shown). Outbred mouse stocks are indicated by underlining. Triangles represent R-6-Br-APB, circles, quinelorane. For clarity and ease of presentation, statistical significance is indicated for male and female rodents combined (see text for any sex differences). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 show increases, paired sample t-test vs. saline, †p<0.05, ††p<0.01, †††p<0.001 show decreases, paired sample t-test vs. saline.

Table I.

Summary of the effects of quinelorane on locomotor activity, by strain

| Strain | Effect | A50 Max. Breaks | A50 Diff. Score | Sex | Sex intx. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprague Dawley | ↑ | 0.014 [0.010–0.018] | 0.015 [0.012–0.021] | ns | ns |

| SPRET/EiJ | ↑ | 0.13 [0.08–0.20] | 0.17 [0.11–0.26] | ns | ns |

| CAST/EiJ | ↑ | 0.30 [0.15–0.61] | 0.43 [0.23–0.84] | M | M |

| C3H/HeJ | ↑ | nc, <0.32 | 0.49 [0.27–0.89] | ns | ns |

| 129S6/SvEvTac | ↓ | nc, <0.032 | nc | ns | ns |

| BALB/cJ | ↓ | nc, <0.032 | nc | F | F |

| Swiss Webster | ↓ | nc, <0.032 | nc | F | F |

| CD-1 (ICR) | ↓ | nc, <0.032 | nc | ns | ns |

| DBA/2J | ↓ | nc, <0.032 | nc | ns | ns |

| C57BL/6J | ↓ | 0.09 [0.07–0.12] | 0.13 [0.10–0.16] | ns | F |

| BALB/cByJ | ↓ | 0.10 [0.06–0.16] | 0.09 [0.05–0.18] | M | F |

| FVB/NJ | ↓ | 0.18 [0.10–0.32] | nc | ns | F |

| A/J | ↓ | nc, <0.32 | nc | F | F |

| 129S1/SvImJ | ↓ | 0.36 [0.21–0.64] | nc | ns | ns |

| SJL/J | - | n/a | n/a | F | ns |

| 129X1/SvJ | - (↑) | n/a | n/a | ns | ns |

Effect: direction of the effect (increased or decreased activity; parenthetical arrow up denotes increased activity only when the dose range was extended to 56 mg/kg). A50 values are group means and 95% confidence intervals, calculated from the individual values for each rodent, in mg/kg. “Max breaks”: estimated dose that produced 50% of the animal’s maximum beam breaks; “Diff score”: estimated dose that produced 50% of the animal’s maximum increase in beam breaks above baseline. Sex: significant main effect of dose, F: female>male effect; M: male>female effect; Sex intx: significant dose by sex interaction; ns: not significant; nc: not calculated; n/a: not applicable.

Table II.

Summary of the effects of R-6-Br-APB on locomotor activity, by strain

| Strain | Effect | A50 Max. Breaks | A50 Diff. Score | Sex | Sex intx. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sprague Dawley | ↑ | 0.19 [0.11–0.32] | 0.26 [0.16–0.42] | ns | F |

| C57BL/6J | ↑ | nc, <0.032 | nc | F | ns |

| DBA/2J | ↑ | nc, <0.32 | 0.09 [0.07–0.12] | ns | ns |

| C3H/HeJ | ↑ | 0.22 [0.13–0.38] | 0.87 [0.50–1.50] | M | F |

| Swiss Webster | ↑ | 0.23 [0.10–0.53] | nc | F | M |

| CD-1 (ICR) | ↑ | 0.35 [0.19–0.63] | 0.78 [0.43–1.40] | ns | M |

| 129S6/SvEvTac | ↑ | 0.39 [0.26–0.59] | 0.46 [0.31–0.68] | ns | ns |

| SJL/J | ↑ | 0.40 [0.24–0.67] | 0.77 [0.49–1.19] | ns | ns |

| 129X1/SvJ | ↑ | 0.40 [0.29–0.56] | 0.44 [0.32–0.60] | ns | ns |

| 129S1/SvImJ | ↑ | 0.41 [0.31–0.53] | 0.47 [0.37–0.60] | M | ns |

| SPRET/EiJ | ↑ | 0.74 [0.52–1.05] | 0.96 [0.66–1.39] | F | ns |

| BALB/cJ | ↓ | nc, <0.032 | nc | F | F |

| FVB/NJ | ↓ | nc, <0.32 | nc | F | F |

| BALB/cByJ | ↓ | 2.15 [1.29–3.60] | 1.28 [0.70–2.33] | M | ns |

| CAST/EiJ | - | n/a | n/a | ns | ns |

| A/J | - | n/a | n/a | ns | ns |

Effect: direction of the effect (increased or decreased activity). A50 values are group means and 95% confidence intervals, calculated from the individual values for each rodent, in mg/kg. “Max breaks”: estimated dose that produced 50% of the animal’s maximum beam breaks; “Diff score”: estimated dose that produced 50% of the animal’s maximum increase in beam breaks above baseline. Sex: significant main effect of dose, F: female>male effect; M: male>female effect; Sex intx: significant dose by sex interaction; ns: not significant; nc: not calculated; n/a: not applicable.

Table III.

Quinelorane-modulated locomotor activity in male and female rats and mice

| Vehicle | 0.0032 mg/kg | 0.01 mg/kg | 0.032 mg/kg | 0.1 mg/kg | 0.32 mg/kg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAT (SD) | M F |

578.9± 49.3 1057.1± 157.2 |

447.1± 60.5 1890.1± 462.8 |

*2998.0± 978.3 *4805.5±1569.9 |

*6746.6± 944.5 ***5414.6±1707.7 |

**6662.3±1300.6 **6139.6±1063.8 |

**7825.6±1146.8 ***6586.1±1130.7 |

|

| Vehicle | 0.032 mg/kg | 0.32 mg/kg | 3.2 mg/kg | 5.6 mg/kg | 18 mg/kg | 56 mg/kg | ||

| FVB | M F |

4733.6± 864.9 8069.9± 336.2 |

*3373.3±1030.3 ***5216.8± 534.5 |

**1150.8± 272.4 ***2101.4± 596.2 |

*2007.4± 465.1 ***1271.0± 290.3 |

*2265.5± 568.8 ***1730.9± 303.9 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| BALB/cJ | M F |

2077.9± 581.1 5636.0± 525.2 |

760.3± 163.5 3354.4± 936.8 |

1065.8± 607.6 **1622.6± 747.5 |

913.1± 485.8 **1796.1754.9 |

*162.4± 36.2 ***379.1± 65.4 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| BALB/cByJ | M F |

5605.6± 245.2 5006.1± 600.7 |

*4245.8± 517.0 3203.9± 375.5 |

***1393.6± 260.0 ***1323.9± 274.0 |

*3589.9± 530.1 *2264.9± 679.2 |

6436.9±1314.2 *2146.1± 496.4 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| C57BL/6J | M F |

2045.0± 208.0 2528.5± 259.6 |

*1573.4± 212.5 *1739.5± 163.5 |

***450.0± 56.7 ***467.5± 70.1 |

***377.7± 40.1 ***247.5± 30.9 |

*1059.4± 177.2 ***302.3± 43.9 |

***481.0± 70.4 ***711.6± 215.5 |

*943.9± 177.5 ***653.8± 86.6 |

| CD-1 (ICR) | M F |

2096.8± 907.4 2341.6± 946.0 |

1670.5± 695.0 1356.5± 341.5 |

955.5± 342.4 328.4± 47.5 |

1305.4± 507.1 539.9± 190.6 |

1648.9±1243.5 1604.4±1214.7 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| CAST/EiJ | M F |

4103.3±1216.5 2786.0±1033.2 |

4593.0± 487.9 4334.8±1215.1 |

**15675.0±2796.2 *9225.4±2420.0 |

**23940.5±1413.9 **18034.8±3248.6 |

*25521.0±1948.6 **18988.6±3341.6 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| Swiss Webster | M F |

983.9± 401.4 3734.0±1058.4 |

883.9± 325.7 *2186.3± 659.6 |

262.4± 85.5 *1109.1± 417.7 |

670.9± 361.3 *1458.8± 462.6 |

1100.0± 571.1 *1317.1± 592.3 |

2704.8± 880.7 1495.0± 473.7 |

2579.0± 678.8 3155.5±1230.5 |

| C3H | M F |

1859.8± 316.2 742.6± 149.4 |

1523.6± 204.8 717.1± 144.3 |

2426.4± 366.3 *1588.4± 387.7 |

*4359.3±1057.5 **3758.1± 844.0 |

3053.5± 676.1 *2950.3± 693.6 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| A/J | M F |

1343.4± 388.7 2237.4± 430.7 |

552.9± 134.2 **819.0± 146.6 |

*365.4± 70.0 **377.3± 49.7 |

*361.1± 108.9 **310.4± 71.2 |

*357.3± 83.5 **229.0± 69.8 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| SJL | M F |

718.3± 142.6 1203.6± 405.8 |

389.0± 98.1 574.3± 145.9 |

522.6± 71.6 782.9± 76.2 |

525.5± 87.6 1149.1± 181.8 |

861.0± 162.6 2020.0±1154.4 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| DBA/2J | M F |

839.1± 56.0 1426.4± 405.4 |

***376.0± 43.2 744.7± 339.1 |

***113.6± 19.5 *162.0± 41.4 |

*335.8± 164.2 497.6± 147.6 |

384.4± 194.0 *179.4± 32.3 |

*257.8± 87.4 *228.8± 79.3 |

Not tested |

| SPRET/EiJ | M F |

531.1± 115.9 816.6± 267.6 |

1262.1± 365.0 *1714.0± 340.2 |

*2969.0± 922.8 *4409.0±1161.6 |

*4326.7±1606.1 *4133.6± 996.6 |

*3764.7±1151.8 **6637.2±1139.0 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| 129S1/SvImJ | M F |

562.0± 81.7 426.1± 49.7 |

413.9± 63.7 **260.0± 53.1 |

**244.6± 34.2 **221.1± 40.9 |

**293.3± 32.3 **189.1± 26.9 |

**360.7± 54.8 341.0± 35.3 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| 129S6/SvEvTac | M F |

490.1± 62.9 475.1± 75.3 |

*279.9± 43.1 288.3± 69.5 |

***124.5± 14.0 *269.0± 59.0 |

*238.9± 21.6 474.0± 108.0 |

*291.6± 42.7 255.4± 44.9 |

Not tested | Not tested |

| 129X1/SvJ | M F |

197.3± 23.8 218.3± 37.3 |

157.9± 24.5 134.8± 23.0 |

148.0± 24.8 143.1± 22.7 |

137.9± 31.5 185.4± 33.6 |

124.9± 14.1 143.1± 37.9 |

156.3± 49.3 232.1± 34.8 |

172.3± 18.5 *479.0± 82.9 |

Values are total beam breaks (3 hrs), group means ± one SEM. In CAST/EiJ mice, 0.0032 mg/kg was also tested: M: 2180.3±430.3, F: 1572.8±1131.2.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 vs. saline.

Table IV.

R-6-Br-APB-modulated locomotor activity in male and female rats and mice

| Vehicle | 0.032 mg/kg | 0.1 mg/kg | 0.32 mg/kg | 1.0 mg/kg | 3.2 mg/kg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAT (SD) | M F |

627.1± 72.0 760.5± 75.1 |

1095.3± 208.7 *2417.4± 674.1 |

**2472.5± 271.8 ***2539.1± 381.4 |

***2477.4± 491.3 **4630.4± 563.4 |

***6015.9±1189.9 **5966.3± 456.1 |

*6468.5±1011.7 **4093.0±948.7 |

| Vehicle | 0.032 mg/kg | 0.32 mg/kg | 3.2 mg/kg | 5.6 mg/kg | |||

| FVB | M F |

4454.4± 987.9 9131.3± 458.3 |

3578.1± 968.3 8688.0± 524.9 |

3419.5± 442.8 ***6751.1± 654.6 |

4168.4± 487.5 ***6051.4± 373.1 |

Not tested | |

| BALB/cJ | M F |

2253.0± 630.8 5320.6± 605.0 |

1257.6± 280.4 4737.0± 708.5 |

3411.3± 480.2 4950.9± 682.5 |

3095.4± 173.4 *3325.7± 409.9 |

2558.9± 197.2 *2602.7± 439.1 |

|

| BALB/cByJ | M F |

6068.5± 591.5 5013.3± 333.9 |

5951.4± 422.9 4366.4± 705.0 |

5583.6± 412.0 *4055.6± 282.0 |

4433.1± 677.8 *3570.4± 459.0 |

*3645.1± 418.4 ***2656.8± 304.6 |

|

| C57BL/6J | M F |

1660.0± 249.5 2176.0± 303.1 |

1767.4± 192.7 *3549.6± 386.3 |

2888.6± 633.3 **3689.3± 321.7 |

*2955.1± 252.6 3004.8± 316.9 |

Not tested | |

| CD-1 (ICR) | M F |

2043.3± 785.2 2348.0± 848.5 |

1854.1± 566.9 2439.5± 835.6 |

*3862.0± 471.7 3507.0± 920.2 |

***10717.5±1353.0 *5791.5± 948.2 |

*6589.8±1867.5 ***7317.7± 781.9 |

|

| CAST/EiJ | M F |

3807.8± 773.8 4975.3± 695.0 |

4215.3± 838.0 3451.3± 776.3 |

3711.3±1200.9 4571.6± 348.7 |

2767.5± 871.3 4061.1±1110.4 |

Not tested | |

| Swiss Webster | M F |

1166.6± 376.4 4201.4±1057.7 |

1480.6± 357.5 3778.9± 725.8 |

**3231.6± 405.6 4024.9± 488.8 |

***4860.3± 385.9 3952.4± 422.0 |

***5377.3± 458.8 5726.3± 547.3 |

|

| C3H | M F |

1660.0± 249.5 2176.0± 303.1 |

1663.1± 218.7 549.5± 68.5 |

1914.4± 202.5 1168.1± 141.4 |

2215.0± 246.0 **2766.4± 451.2 |

2945.8± 481.9 *1718.0± 349.2 |

|

| A/J | M F |

1481.3± 181.6 1050.0± 219.5 |

1372.6± 229.1 905.4± 191.1 |

1739.9± 448.8 1466.1± 235.5 |

1621.9± 98.0 1903.5± 152.8 |

1568.0± 225.2 1466.0± 208.8 |

|

| SJL | M F |

657.9± 110.2 1233.5± 248.7 |

934.1± 202.9 988.6± 177.3 |

**1463.5± 215.5 1914.8± 326.8 |

**2885.8± 396.7 **3437.6± 349.0 |

***3195.6± 219.0 4205.5±1725.0 |

|

| DBA/2J | M F |

1283.1± 262.4 762.6± 156.1 |

1414.0± 258.8 1058.4± 213.9 |

*2818.9± 598.8 **1999.7± 177.6 |

Not tested 3624.8±1092.5 |

Not tested | |

| SPRET/EiJ | M F |

485.7± 69.3 832.5± 110.7 |

572.9± 113.7 1102.5± 191.3 |

*1807.1± 386.4 1961.5± 558.5 |

***5801.6± 842.7 ***6843.7± 585.2 |

***4651.6± 407.2 **7536.8± 854.4 |

|

| 129S1/SvImJ | M F |

569.0± 96.4 529.3± 65.3 |

896.5± 191.6 515.1± 47.0 |

**3626.3± 599.8 ***2673.0± 225.6 |

***8436.0± 815.2 ***6838.5± 375.9 |

3145.5±1590.3 Not tested |

|

| 129S6/SvEvTac | M F |

386.9± 69.0 394.0± 74.2 |

359.8± 87.1 333.4± 66.4 |

***1983.0± 277.8 **1690.3± 318.7 |

***5672.0± 398.8 **4394.9± 949.5 |

**2863.9± 472.6 **2306.9.6± 448.5 |

|

| 129X1/SvJ | M F |

326.9± 74.3 245.8± 30.2 |

239.8± 51.8 290.4± 54.8 |

***3334.5± 376.4 **1865.3± 316.1 |

**6929.9±1271.7 ***5669.5± 605.1 |

Not tested | |

Values are total beam breaks (3 hrs), group means ± one SEM.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001 vs. saline.

In agreement with previous reports, both the D2-like agonist quinelorane and the D1-like agonist R-6-Br-APB significantly and dose-dependently increased locomotor activity in the Sprague Dawley rats [F(5,65)=16.4, p<0.001 and F(5,55)=18.0, p<0.001, respectively]. There was no main effect of sex with either drug, and no significant quinelorane by sex interaction. There was a R-6-Br-APB by sex interaction [F(5,55)=2.8, p<0.05], although R-6-Br-APB increased locomotor activity in both female rats [F(5,25)=7.5, p<0.001] and male rats [F(5,30)=14.1, p<0.001]. The interaction appeared attributable to a slightly higher potency in females, in which the effect peaked at 1.0 mg/kg with a decline of the effect at 3.2 mg/kg, while in the male rats activity uniformly increased with dose. Calculated potencies for females and males were 0.12 and 0.30 mg/kg, respectively, but with overlapping confidence intervals (0.06–0.24 vs. 0.14–0.63).

I. Effects of quinelorane on total beam breaks

I.A Quinelorane decreased locomotor activity in most mouse strains

In contrast to the rats, quinelorane decreased activity in nine of the fifteen mouse strains (see Fig. 1). Quinelorane significantly decreased activity in the FVB/NJ [F(4,56)=38.1, p<0.001], BALB/cJ [F(4,52)=11.9, p<0.001], BALB/cByJ [F(4,56)=12.4, p<0.001], C57BL/6J [F(4,52)=61.8, p<0.001], Swiss Webster [F(6,84)=3.7, p<0.001], A/J [F(4,52)=15.3, p<0.001], DBA/2J [F(4,52)=8.8, p<0.001], 129S1/SvImJ [F(4,56)=13.9, p<0.001], and 129S6/SvEvTac [F(4,56)=6.2 p<0.001]. The CD-1 mice showed a shallow U-shaped curve, and the dose effect was significant only when the highest dose was excluded [F(3,42)=4.9, p<0.005]. The statistical significance of individual doses relative to vehicle in each strain can be seen in Figure 1. In most strains, activity either decreased over the tested dose range or decreased to a plateau, but some strains displayed a U-shaped curve with only intermediate doses significantly different from vehicle (BALB/cByJ, Swiss Webster, CD-1). Increasing the dose range to 18 or 56 mg/kg in the Swiss Webster, C57BL/6J, and DBA/2J mice did not yield significant increases in activity, although qualitative effects such as brief sequences of backwards locomotion were observed at those doses (data not shown as sexes combined, but see Table III).

In several strains, there were also main effects of sex and/or dose by sex interactions (see Table III). In the BALB/cJ and BALB/cByJ strains, there was both a main effect of sex ([F(1,13)=16.5, p<0.001] and [F(1,13)=13.0, p=0.003], respectively), and a quinelorane by sex interaction ([F(4,52)=3.5, p=0.01], [F(4,56)=3.8, p=0.008]). In the BALB/cJ, the female mice showed higher activity levels than the male mice over the dose range, including markedly higher baseline levels. Because quinelorane decreased locomotor activity in both female [F(4,24)=8.8, p<0.001] and male [F(4,28)=2.9, p=0.04] mice, the interaction was most likely attributable to this baseline difference. In contrast, in the BALB/cByJ strain, the male mice had higher activity levels over the dose range, and the interaction appeared attributable to the highest dose: quinelorane significantly decreased activity in the males [F(4,28)=8.4, p<0.001], but with a U-shaped dose-effect curve, compared to a monotonic decrease in the females [F(4,28)=7.6, p<0.001].

In the C57BL/6J, FVB/NJ, and Swiss Webster mice, there was no significant main effect of sex, but a quinelorane by sex interaction ([F(4,52)=4.5, p=0.004], [F(4,56)=6.2, p<0.001], and [F(4,56)=2.8, p=0.04], respectively). In the C57BL/6J strain, quinelorane decreased locomotor activity in both female [F(4,28)=56.6, p<0.001] and male [F(4,24)=17.3, p<0.001] mice. The interaction appeared attributable to the highest quinelorane dose, since the dose-effect curve appeared U-shaped in the males and monotonic in the females. In FVB/NJ mice, higher baseline levels of locomotion in female than male mice (see Table III) most likely explain the interaction, as quinelorane decreased locomotor activity in both the female [F(4,28)=44.1, p<0.001] and the male [F(4,28)=6.9, p=0.001] mice. Finally, in Swiss Webster mice, quinelorane significantly decreased locomotor activity in female mice [F(4,28)=5.9, p=0.001] but had no significant effect in male mice up to 5.6 mg/kg. Thus there was no general trend in either main effects of sex or in sex by quinelorane interactions; most sex effects were attributable to baseline differences or to the presence or absence of an ascending limb of the dose-effect curve at the highest dose of quinelorane.

To assess quinelorane’s potency in each strain, we calculated A50 values, as the mean dose estimated to increase activity to 50% of the maximal effect in each strain, both calculated as 50% of the total beam breaks, and as 50% increase in beam breaks over baseline level (difference score). Quinelorane was more potent in the strains in which it decreased activity, than in the strains in which it increased activity (see Table I, and results below). Indeed, for decreases in activity, quinelorane typically showed significant effects at the lowest dose tested. Thus A50 values could only be calculated for a few strains, because the lowest dose elicited more than 50% of the maximum effect in a large number of mice (see Methods for details). Of these strains, the 129S1/SmImJ strain exhibited the lowest potency (see Table V).

Table V.

Quinelorane potency comparisons between strains (increased and decreased activity).

| Increase | SD rat | SPRET | CAST | C3H |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD RAT | X | ** | ** | n/a |

| SPRET | ** | X | - | n/a |

| CAST | ** | - | X | n/a |

| C3H | ** | * | - | X |

| Decrease | C57 | BALB/cBy | FVB | 129S1 |

| C57 | X | - | - | ** |

| BALB/CBY | - | X | n/a | n/a |

| FVB | n/a | n/a | X | n/a |

| 129S1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | X |

Upper/right half: Comparisons of A50 values calculated as maximum beam breaks; lower/left half: comparisons of A50 values calculated as difference score.

overlapping 95% confidence intervals,

non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals,

non-overlapping 99% confidence intervals.

n/a: not applicable (A50 value could not be estimated).

I.B Quinelorane increased locomotor activity in three mouse strains

Only three strains of mice showed increased locomotor activity after quinelorane administration: CAST/EiJ mice [F(5,20)=35.7, p<0.001], C3H/HeJ [F(4,52)=11.8, p<0.001], and SPRET/EiJ [F(4,40)=20.0, p<0.001] (see Fig. 1). Quinelorane was particularly efficacious in this regard in CAST/EiJ mice, eliciting peak activity levels far higher than any other strain with either drug, including the rats (note the special axes for CAST/EiJ in Fig. 1). We therefore tested an additional low dose, 0.0032 mg/kg, in this strain. There was also a main effect of sex [F(1,4)=23.5, p=0.008] and a quinelorane by sex interaction [F(5,20)=3.1, p=0.03] in the CAST/EiJ mice. The males had higher levels of locomotor activity than the females overall, and the interaction seemed attributable to a larger effect of the high doses in the males (see Table III), although quinelorane increased locomotion in both female [F(5,10)=7.4, p=0.004] and male [F(5,10)=39.4, p<0.001] mice. There was no significant effect of sex or sex by dose interaction in the C3H/HeJ or SPRET/EiJ.

A50 values for locomotor activating effects of quinelorane, calculated from total beam breaks and from difference scores, showed good agreement in ranking order between the two measures (Table I). In the three strains in which quinelorane did increase locomotor activity, the potency was 10- to 30-fold lower relative to the rats (see Table I), a significant difference based on non-overlapping 95% and 99% confidence intervals of the A50 values (see Table V). Of these three mouse strains, the SPRET/EiJ mice had the lowest A50 values, and the C3H/HeJ the highest.

I.C Quinelorane had no effect on locomotor activity in two mouse strains

When analyzed in the dose range shown, quinelorane failed to significantly alter locomotor activity in two of the mouse strains: the SJL/J (p=0.08) and 129X1/SvJ (p=0.09) mice (see Fig. 1). There was also no sex by dose interaction in these strains. However, when the dose range was extended to 56 mg/kg in the 129X1/SvJ strain, a small but significant increase in activity was observed [F(6,89)=7.9, p<0.001], albeit in the females only [F(6,42)=10.2, p<0.001] (data not shown in as sexes combined, but see Table III).

II. Effects of R-6-Br-APB on total beam breaks

II.A R-6-Br-APB increased locomotor activity in most mouse strains

Similar to its effect in the rats, the D1-like agonist R-6-Br-APB produced increased locomotor activity in ten of the fifteen mouse strains tested: C57BL/6J [F(3,39)=5.0, p=0.005], CD-1/ICR [F(4,52)=22.9, p<0.001], Swiss Webster [F(4,48)=9.2, p<0.001], C3H/HeJ [F(4,56)=10.4, p<0.001], SJL/J [F(4,56)=9.7, p<0.001], DBA/2J [F(2,24)=17.8, p<0.001], SPRET/EiJ [F(4,40)=57.2, p<0.001], 129S1/SvImJ [F(3,42)=157.4, p<0.001], 129S6/SvEvTac [F(4,56)=42.9, p<0.001], and 129X1/SvJ [F(3,45)=56.8, p<0.001]. The statistical significance of individual doses relative to vehicle in each strain can be seen in Figure 1.

As with quinelorane, there were main effects of sex and dose by sex interactions in some of these strains (see Table IV for data averaged by sex, and doses statistically significant from vehicle). There was a main effect of sex in the 129S1/SvImJ [F(1,14)=5.1, p=0.04], SPRET/EiJ effect [F(1,10)=8.3, p=0.02] and C57BL/6J [F(1,13)=7.7, p=0.02], but no significant dose by sex interaction. Thus in the 129S1/SvImJ and SPRET/EiJ strains, the male mice had higher activity levels than the female mice over the dose range, whereas in C57BL/6J mice the females showed higher activity. In the C3H/HeJ and Swiss Webster strains, there was both a main effect of sex ([F(1,14)=9.6, p=0.008] and [F(1,12)=7.0, p=0.02], respectively) and a drug by sex interaction ([F(4,56)=3.5, p=0.01] and [F(4,48)=4.7, p=0.003], respectively). The male C3H/HeJ mice had more than 2-fold higher baseline activity levels relative to the female mice (see Table IV). The interaction in the C3H/HeJ reflected a markedly larger effect of R-6-Br-APB in the female mice than in the male mice, as no dose achieved significance relative to saline in the males despite a significant overall dose effect [F(4,28)=3.4, p=0.02] (the highest approached significance, p=0.07), whereas the two highest doses reached significance in the females [main effect F(4,28)=10.6, p<0.001]. In the Swiss Webster, the effects reflected both higher baseline activity in the females than in the males, and a lack of effect of R-6-Br-APB in the females as opposed to a significant locomotor activating effect in the males [F(4,24)=23.5, p<0.001]. Finally, in the CD-1/ICR, there was no main effect of sex, but a drug by sex interaction [F(4,52)=3.7, p=0.01]. The interaction in this strain was likely attributable to both a higher peak effect in the males than in the females, and a higher potency in the males, although R-6-Br-APB increased locomotor activity in both female [F(4,24)=12.2, p<0.001] and male [F(4,28)=15.0, p<0.001] (see Table III). In summary, as described for quinelorane above, there was also no general trend in either main effects of sex or in sex by dose R-6-Br-APB interactions, with sex effects in both directions.

R-6-Br-APB’s potency was assessed in the same way as for quinelorane, and A50 values are reported in Table II. In contrast to quinelorane, the potency of R-6-Br-APB to increase locomotor activity in the mouse strains was only moderately lower relative to the rats, reaching significance only when calculated as the difference score in most cases (see Tables II and VI). One notable exception was the DBA/2J strain, for which R-6-Br-APB’s potency was significantly higher than in all other strains in which an A50 could be calculated, including the rats.

Table VI.

R-6-Br-APB potency comparisons between strains (increased activity).

| Strain | SD rat | DBA | C3H | SW | CD-1 | 129S6 | SJL | 129X1 | 129S1 | SPRET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD rat | X | n/a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | * |

| DBA | * | X | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| C3H | * | * | X | - | - | - | - | - | - | * |

| SW | n/a | n/a | n/a | X | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CD-1 | * | * | - | n/a | X | - | - | - | - | - |

| 129S6 | - | * | - | n/a | - | X | - | - | - | - |

| SJL | * | * | - | n/a | - | - | X | - | - | - |

| 129X1 | - | * | - | n/a | - | - | - | X | - | - |

| 129S1 | - | * | - | n/a | - | - | - | - | X | - |

| SPRET | * | * | - | n/a | - | - | - | * | * | X |

Upper/right half: Comparisons of A50 values calculated as maximum beam breaks; lower/left half: comparisons of A50 values calculated as difference score.

overlapping 95% confidence intervals,

non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals,

non-overlapping 99% confidence intervals.

n/a: not applicable (A50 value could not be estimated).

II.B R-6-Br-APB decreased locomotor activity in three mouse strains

Contrary to its effect in rats and most of the mouse strains, we found that R-6-Br-APB decreased locomotor activity in three of the mouse strains: the FVB/NJ [F(3,42)=4.4, p=0.009], the BALB/cJ [F(4,52)=5.0, p=0.002], and the BALB/cByJ mice [F(4,56)=10.7, p<0.001] (see Fig. 1). There were also sex effects found in these three strains (see Table IV). In all three strains activity levels were markedly higher in the females relative to the males, including under vehicle conditions (main effect of sex, FVB/NJ, [F(1,14)=37.7, p<0.001], BALB/cJ, [F(1,13)=13.2, p=0.003], BALB/cByJ, [F(1,14)=7.7, p=0.02]),.

In the FVB/NJ mice, there was also a dose by sex interaction [F(3,42)=3.3, p=0.03], most likely reflecting the fact that R-6-Br-APB decreased locomotor activity in female mice [F(3,21)=19.5, p<0.001] and not in males. There was also a significant drug by sex interaction in the BALB/cJ mice [F(4,52)=7.6, p<0.001] (but not in the BALB/cByJ). As in the FVB/NJ mice, no dose reached significance relative to saline in the male BALB/cJ mice despite a significant main effect [F(4,28)=5.0, p=0.004], while the two highest doses significantly decreased activity in the female relative to saline [main effect F(4,24)=7.1, p=0.001]. R-6-Br-APB’s potency could only be accurately estimated for the BALB/cByJ strain (Table II), in which potency was about an order of magnitude lower compared to rats.

II.C R-6-Br-APB had no effect on locomotor activity in two mouse strains

R-6-Br-APB failed to significantly alter locomotor activity in A/J mice (p=0.08, with a trend towards increased activity, see Fig. 1) and CAST/EiJ mice (p=0.3, no discernable trend). The drug treatment was not devoid of effect, as adverse health consequences (e.g., seizures, irregular/gasping breathing) were observed at 3.2 mg/kg in the CAST/EiJ mice.

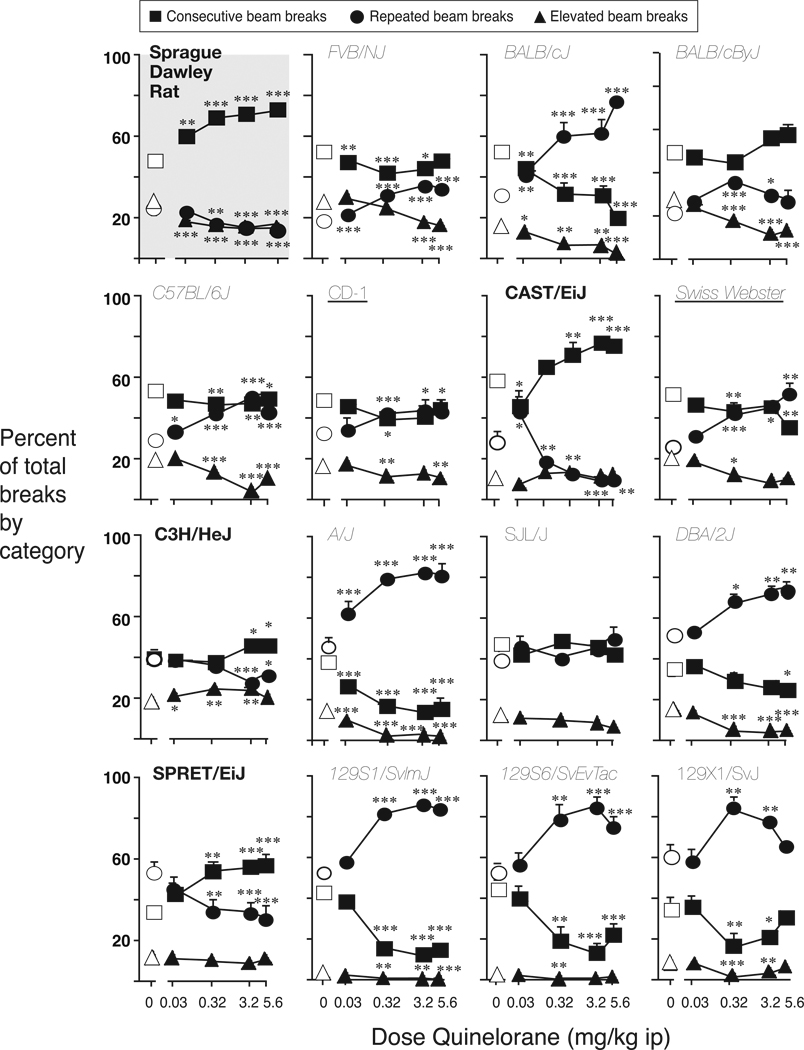

III. Qualitative modulation of locomotor activity by quinelorane

Comparison of beam break distribution after vehicle injection (“baseline”) showed a significant strain by beam break type interaction [F(32,456)=17.6, p<0.0001]. Consequently, the modulation of beam break distribution by quinelorane was analyzed separately for each strain. Figure 2 shows the distribution of beam breaks as percentage of the total, summed over 3 hours after administration of quinelorane, for each strain (shown in the same order as in Figure 1). To facilitate the comparison to Figure 1 and the effect of quinelorane on total beam breaks, the name of the strains that showed increased activity (as described above) are in bold, while the names of strains that showed decreased activity are in italics. At baseline, breaks of elevated beams (consistent with rearing) typically accounted for less than one third of the total activity, consecutive beam breaks (consistent with ambulation) accounted for most of the beam breaks in the rats and in about half of the mouse strains, while repeated breaks of a same beam (consistent with fine movement) accounted for most of the beam breaks in the remaining mouse strains (see Fig. 2). Strains in which repeated beam breaks accounted for a high proportion of activity at baseline appeared clustered in the bottom panels; in other words, strains with high baseline activity showed high percents of consecutive beam breaks, while the lower baseline strains tended to exhibited higher percentages of repeated breaks.

Figure 2.

Distribution of behavior defined by interruption of consecutive beams, repeated breaks of the same beam and breaks of elevated beams, as a function of quinelorane dose. Abscissa: quinelorane dose in mg/kg, i.p.; ordinate: % of total beam breaks over 3-hour session. Data are group means, bars represent one SEM. Group sizes as in Figure 1. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 paired sample t-test vs. saline within each break type.

Quinelorane affected the distribution of beam breaks significantly in the rats and in all but the SJL/NJ mouse strain, reflected by a significant dose by beam break type interaction: Sprague Dawley rats [F(8,112)=17.1, p<0.001], FVB/NJ [F(8,112)=12.2, p<0.001], BALB/cJ [F(8,104)=16.3, p<0.001], BALB/cByJ [F(8,112)=8.6, p<0.001], C57BL/6J [F(8,104)=18.2, p<0.001], CD-1/ICR [F(8,104)=3.0, p=0.005], CAST/EiJ [F(10,40)=19.2, p<0.001], Swiss Webster [F(8,80)=6.6, p<0.001], C3H/HeJ [F(8,104)=5.5, p<0.001], A/J [F(8,96)=15.2, p<0.001], DBA/2J [F(8,104)=4.9, p<0.001], SPRET/EiJ [F(8,80)=10.8, p<0.001], 129S1/SvImJ [F(8,104)=23.0, p<0.001], 129S6/SvEvTac [F(8,104)=8.8 p<0.001], and 129X1/SvJ [F(8,112)=5.9, p<0.001]. Thus quinelorane had a significant effect on locomotor activity qualitatively, including in two of the three strains in which the same dose range failed to significantly alter total beam breaks (i.e., the 129X1/SvJ and CD-1/ICR).

The proportion of consecutive beam breaks increased with dose in all strains in which total activity was increased: the Sprague Dawley rats, CAST/EiJ, C3H/HeJ and SPRET/EiJ (see Fig. 2). In contrast, the proportion of consecutive beam breaks decreased with dose in all strains in which total activity was decreased, with the exception of the BALB/cByJ, in which the percent consecutive beam breaks was not significantly affected (see Fig. 2 for doses significant from saline in each strain). The proportion of consecutive beam breaks also decreased with dose in the CD-1/ICR and the 129X1/SvJ strains, in which quinelorane’s effect on total activity did not reach significance. The proportion of repeated beam breaks increased with the dose of quinelorane in the strains where total activity and consecutive breaks increased, again with the only exception of the BALB/cByJ, in which a small increase in the proportion of repeated beam breaks was seen (see Fig. 2). Conversely, the proportion of repeated beam breaks decreased in the strains displaying increased total activity and consecutive breaks. Finally, the proportion of elevated beam breaks showed modest decreases as a function of quinelorane dose in most strains, including in the rats (in which total activity was increased), but was decreased or not significantly affected in the mouse strains showing overall locomotor activation (increased in the C3H/HeJ, unchanged in the CAST/EiJ and SPRET/EiJ). In summary, quinelorane-induced changes in total activity were rather consistently paralleled by the qualitative modulation of consecutive beam breaks (ambulation) relative to repeated or elevated beam breaks, while the proportion of repeated beam breaks (fine movement) was modulated in the opposite direction, and elevated beam breaks (rearing) tended to be decreased or unchanged.

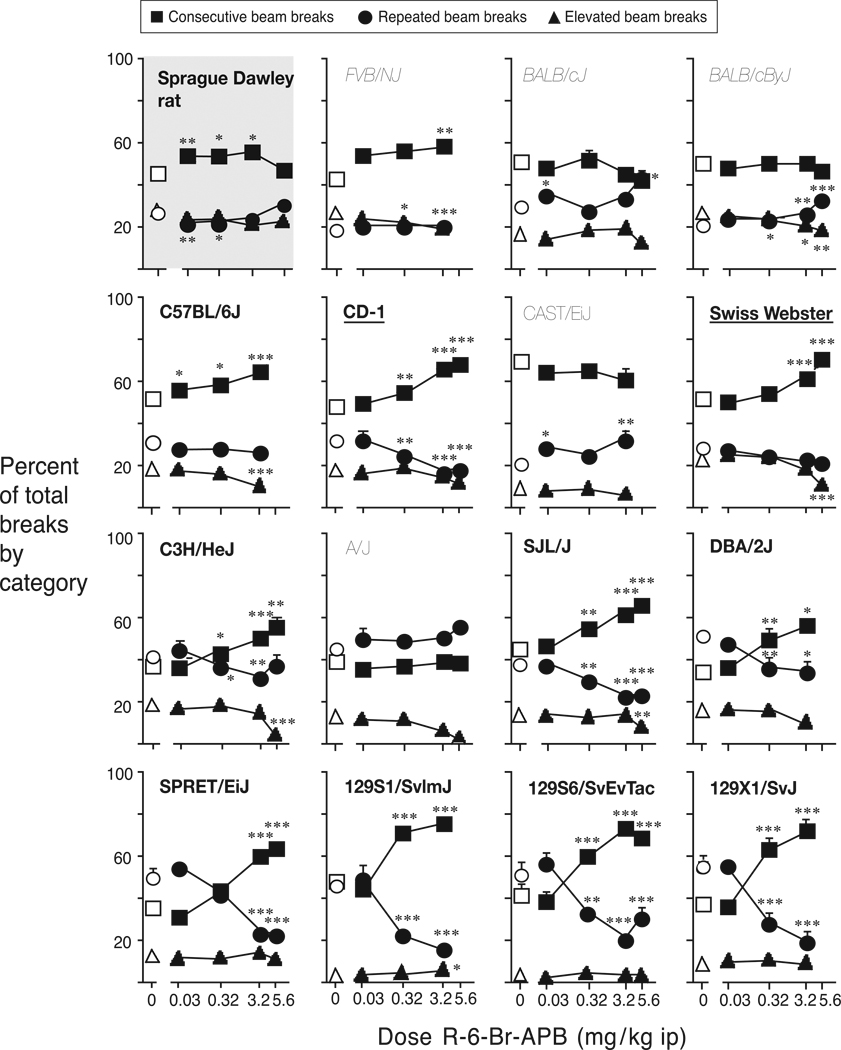

IV. Qualitative modulation of locomotor activity by R-6-Br-APB

As with quinelorane, there was a strain by beam break type interaction at baseline [F(30,456)=13.4, p<0.0001]. Indeed, the comparison of beam break distribution after vehicle injection in the quinelorane experiment and in the R-6-Br-APB experiment showed no significant interaction between break type and strain or experiment (p>0.3), indicating that the distinct qualitative distribution of break type in each strain (following vehicle) was replicable. The modulation of beam break distribution by R-6-Br-APB was analyzed as for quinelorane, and data are presented in Figure 3, using the same arrangement of the strains. To facilitate the comparison to Figure 1 and the effect of R-6-Br-APB on total beam breaks, the name of the strains that showed increased total beam breaks are in bold, while the names of strains that showed decreased activity are in italics.

Figure 3.

Distribution of behavior defined by interruption of consecutive beams, repeated breaks of the same beam and breaks of elevated beams, as a function of R-6-Br-APB dose. Abscissa: R-6-Br-APB dose in mg/kg, i.p.; ordinate: % of total beam breaks over 3-hour session. Data are group means, bars represent one SEM. Group sizes as in Figure 1. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 paired sample t-test vs. saline within each break type.

R-6-Br-APB affected the distribution of beam breaks in the rats and in all but the A/J mouse strain, reflected by a significant dose by beam break type interaction: Sprague Dawley rats [F(8,104)=3.0, p=0.004], FVB/NJ [F(6,84)=5.2, p<0.001], BALB/cJ [F(8,104)=4.0, p<0.001], BALB/cByJ [F(8,112)=5.7, p<0.001], C57BL/6J [F(6,78)=9.4, p<0.001], CD-1/ICR [F(8,104)=16.8, p<0.001], CAST/EiJ [F6,48)=4.0, p=0.002], Swiss Webster [F(8,96)=15.4, p<0.001], C3H/HeJ [F(8,112)=10.3, p<0.001], SJL/NJ [F(8,112)=15.9, p<0.001], DBA/2J [F(4,48)=9.2, p<0.001], SPRET/EiJ [F(8,80)=31.0, p<0.001], 129S1/SvImJ [F(6,84)=28.0, p<0.001], 129S6/SvEvTac [F(8,112)=23.6 p<0.001], and 129X1/SvJ [F(6,78)=44.5, p<0.001]. Thus R-6-Br-APB had a significant effect on locomotor activity qualitatively, including in the CAST/EiJ mice, in which the same dose range failed to significantly alter total beam breaks. Beam break distribution remained unaffected in the A/J mice, the only other strain that did not show a change in total activity with R-6-Br-APB.

The proportion of consecutive beam breaks increased with dose in all strains in which total activity increased, and also in the FVB/NJ mice, in which total beam breaks were decreased by R-6-Br-APB (see Fig. 3 for the significance of specific doses relative to vehicle in each strain). The proportion of consecutive beam breaks was not affected significantly in the two BALB substrains or in the CAST/EiJ mice, the former strains showing decreased total activity levels and the latter showing no effect. R-6-Br-APB did not decrease the proportion of consecutive beam breaks in any of the strains. The proportion of repeated beam breaks tended to decrease with dose of R-6-Br-APB in the strains in which consecutive beam breaks were increased, although it was not significantly affected in FVB/NJ, C57BL/6J, and Swiss Webster mice. The proportion of repeated beam breaks was increased by R-6-Br-APB only in the two BALB substrains and in the CAST/EiJ strain. Finally, the proportion of elevated beam breaks was unchanged by R-6-Br-APB treatment in most strains, and moderately decreased in some: BALB/cByJ, C57BL/6J, Swiss Webster, C3H/HeJ and SJL/J. In summary, R-6-Br-APB-induced increases in total activity were rather consistently paralleled by increases in the proportion of consecutive beam breaks (consistent with ambulation) relative to repeated and elevated beam breaks, (as observed for quinelorane), while decreased total activity levels were accompanied by increases in the proportion of repeated beam breaks (consistent with fine movements).

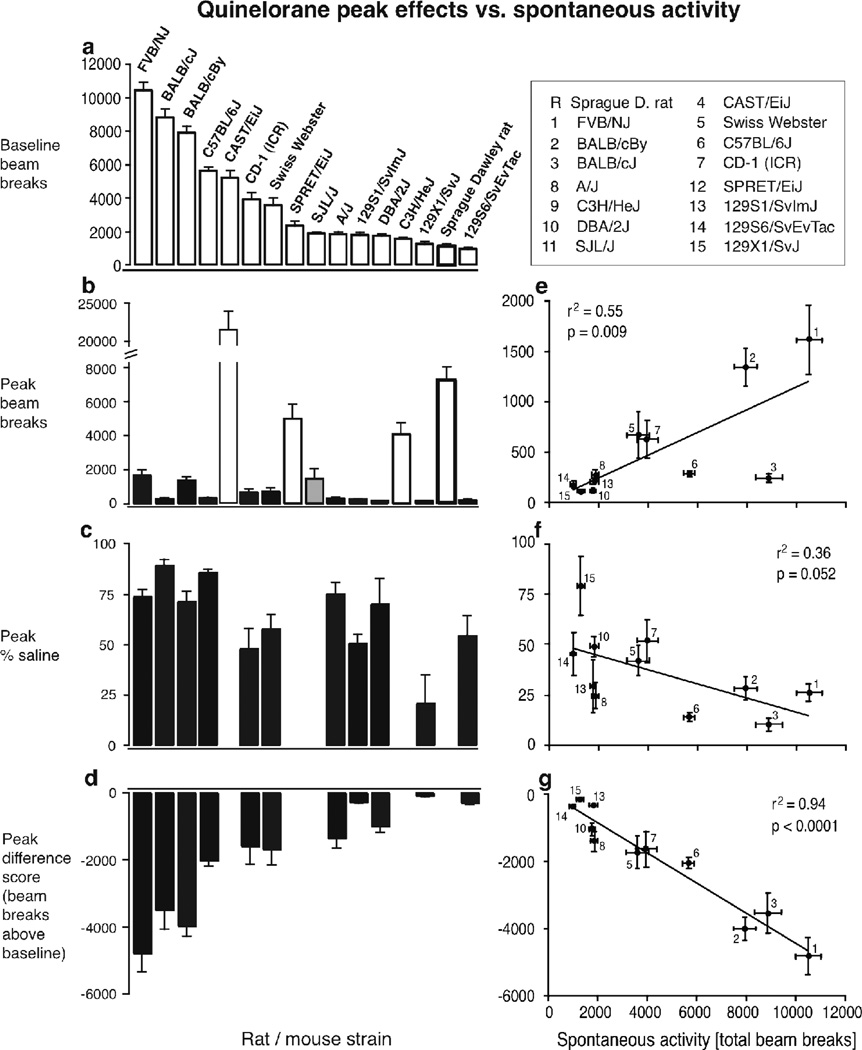

V. Predictive value of spontaneous activity for stimulant effects of quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB

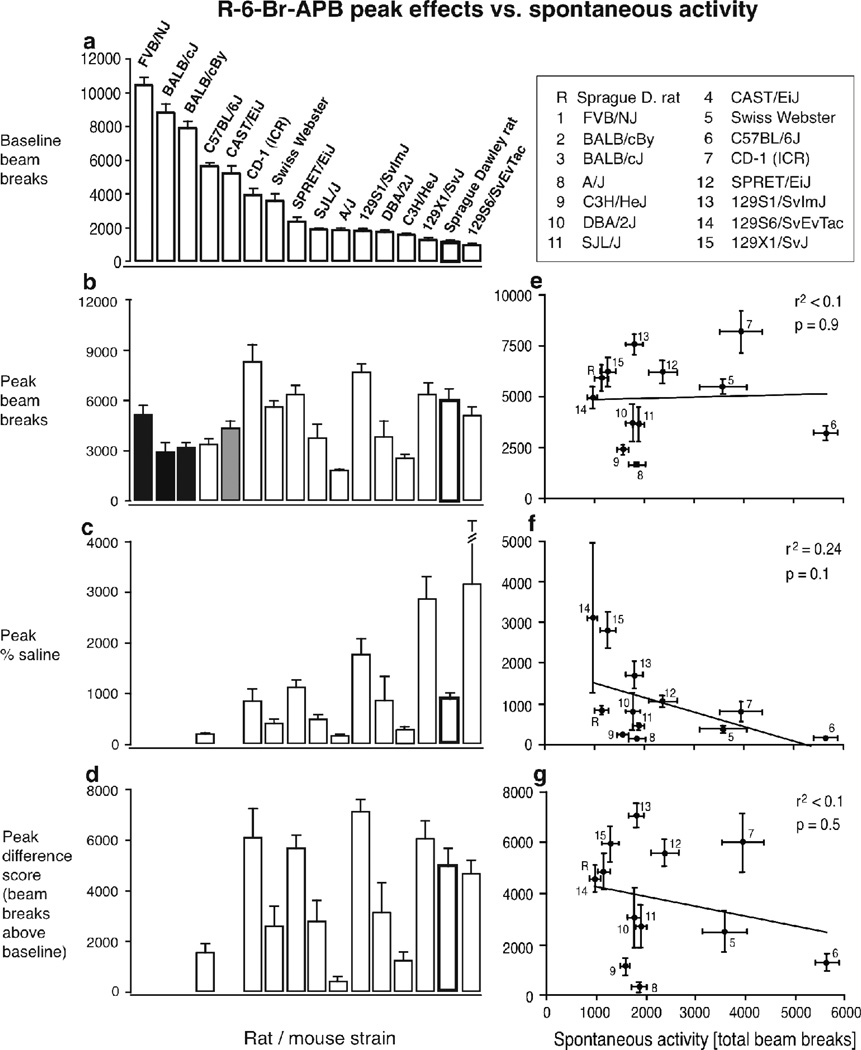

Figure 4a–d shows peak effects of quinelorane as total beam breaks (b), as percent of baseline activity (c), and as a difference score (d; i.e., increase in activity above baseline, in beam breaks) as well as spontaneous activity as total beam breaks (a). In panel b, increases in activity are shown as white bars, no significant effect as gray bars, and decreased activity as black bars. In panels c and d, data points are shown only for decreased activity (11 of 16 strains). Figure 4e–g shows the same peak effects, as total beam breaks (e), percent baseline (f) and difference scores (g), but plotted as functions of baseline activity levels, showing correlations between baseline and peak drug effects

Figure 4.

Relationship between spontaneous activity and quinelorane-modulated activity levels across strains. Abscissa: spontaneous activity levels in total beam breaks per 4-hr session; ordinates: beam breaks or modified peak effect measures as indicated. Each point represents a strain, identified by numbers (see legend). Black (filled) bars represent decreases in activity from vehicle, white (open) bars increases in activity, and grey bars, no change (panels b–d). Rat data are highlighted by thicker outlines. Data are group means, bars represent one s.e.m. for spontaneous activity (horizontal bars) and drug-modulated (vertical) activity. Correlations between spontaneous activity and drug-modulated activity levels are indicated (panels e–g).

While there were marked differences in spontaneous activity between strains, the spontaneous activity levels did not predict the direction of quinelorane’s effects: quinelorane increased locomotor activity in a strain ranking relatively high in spontaneous activity (CAST/EiJ), a strain with intermediate spontaneous activity (SPRET/EiJ) and some rodents with rather low spontaneous activity levels (C3H/HeJ mice and Sprague Dawley rats, see Fig. 4b). However, among the strains in which quinelorane decreased locomotor activity, there was a highly significant correlation between spontaneous activity and peak activity (r2=0.55, p=0.009, positive correlation, see Fig. 4e), and peak difference score (r2=0.94, p<0.0001, negative correlation, see Fig. 4g), while the correlation between spontaneous activity and peak as percent of baseline narrowly escaped significance (r2=0.36, p=0.052, negative correlation). In summary, the strains that exhibited the highest levels of spontaneous activity still showed the highest activity levels after quinelorane administration, overall, but also showed the greatest decreases in activity from baseline.

Figure 5a–d shows peak effects similarly to Figure 4, but for R-6-Br-APB. In panels c and d, data points are shown only for strains with increased activity (12 of 16 strains including the A/J, which showed a non-significant trend for increased activity). Interestingly, R-6-Br-APB decreased activity in only the strains with the highest spontaneous activity levels (see Fig. 5a,b), and increased activity in most strains. Among the strains that showed increased activity, spontaneous activity levels did not predict peak beam break levels, peak as %baseline, or peak activity as difference scores.

Figure 5.

Relationship between spontaneous activity and R-6-Br-APB-modulated activity levels across strains. Details as in Figure 4.

DISCUSSION

The present data confirm and extend our previous report in a smaller number of strains, that most mouse strains showed locomotor stimulation with the D1-like agonist R-6-Br-APB, but not with the D2-like agonist quinelorane (Ralph & Caine, 2005). We also identified three strains of mice in which D2 stimulation did produce locomotor hyperactivity (C3H, SPRET/EiJ, and CAST/EiJ) and the first two of those three strains showed hyperactivity following both a D1-like and a D2-like agonist similar to Sprague Dawley rats. Interestingly, those locomotor hyperactivity profiles parallel profiles using measures of decreased prepulse inhibition of startle (Ralph & Caine, 2005, 2007), suggesting that these species and strain profiles in responses to D1-like and D2-like stimulation are replicable across studies and behavioral assays. We found no general trend for differences between male and female rodents, although significant sex differences in sensitivity to D1-like and/or D2-like stimulation emerged in several strains. These data should prove useful in helping select suitable background/parent strains for future studies using mutant (e.g., knockout, knock-in, transgenic) animals or recombinant inbred strains.

Species and strain differences in effects of quinelorane

Decreases in locomotor activity after administration of D2-like agonists including quinelorane have previously been reported in C57BL/6J, CF-1, NMRI and Swiss Webster mice (Chang, Geyer, Buell, Weber & Swerdlow, 2010; Frances, Smirnova, Leyris, Aymard & Bourre, 2001; Geter-Douglass, Katz, Alling, Acri & Witkin, 1997; Halberda, Middaugh, Gard & Jackson, 1997; Li et al., 2010; Wilmot, Fico, Vanderwende & Spoerlein, 1989). D2-like agonists likewise decreased locomotor activity in wild-type mice of mixed 129/SvJ / C57BL/6J background as well as littermate knockout mice lacking D3 receptors, but not in D2 receptor knockout mice (Boulay, Depoortere, Perrault, Borrelli & Sanger, 1999; Boulay, Depoortere, Rostene, Perrault & Sanger, 1999; Li et al., 2010). Those data suggest the locomotor suppressing effects of D2-like agonists in mice are attributable to stimulation of D2, rather than D3 or D4 receptors. More specifically, the D2-like agonist quinpirole decreased locomotor activity as much or more in D2L-specific knockout mice relative to wild-types, suggesting this effect is due to D2S rather than D2L stimulation (Usiello et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000). This makes sense since the short isoform of the receptor (D2S) represents mainly inhibitory presynaptic autoreceptors, and the long isoform (D2L), mainly serves as postsynaptic receptors (Centonze et al., 2002; Lindgren et al., 2003; Usiello et al., 2000). It is also intriguing that quinelorane produced other effects reminiscent of D2 receptor blockade, such as antagonizing the locomotor stimulant effects of caffeine or the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801, and protecting against convulsant effects of cocaine, in Swiss Webster mice – effects which appear consistent with stimulation of inhibitory D2 autoreceptors (Cook & Beardsley, 2003; Cook, Newman, Winfree & Beardsley, 2004; Witkin et al., 2004).

Low doses of D2-like agonists decrease locomotor activity in rats, an effect also likely attributable to stimulation of D2 autoreceptors, and/or, perhaps, to D3 receptor stimulation (Bristow et al., 1996; Eilam & Szechtman, 1989; Millan, Seguin, Gobert, Cussac & Brocco, 2004; Pugsley et al., 1995). Therefore one possible interpretation of the decreased activity in most mouse strains could be that the dose-effect curve is shifted markedly to the right in mice relative to rats, so that the doses tested in the present study fell below the ascending limb of the curve. The U-shaped curve in some strains (BALB/cByJ, CD-1, Swiss-Webster SJL/J) would support this interpretation, as does a recent investigation in which 100 mg/kg quinpirole or 7-OH-DPAT produced increases in locomotor activity in male Swiss-Webster mice (Li et al., 2010). In addition, for both increased and decreased activity, the calculated potency of quinelorane in the present study was about 10-fold (or more) lower in all mouse strains relative to the Sprague-Dawley rats. Here we tested doses up to 56 mg/kg quinelorane in selected strains (the commonly used 129X1/SvJ, C57BL/6J, Swiss Webster), and observed a significant (two-fold) increase in total beam breaks only in the female 129X1/SvJ mice. On the other hand, for several strains, toxic effects of quinelorane (e.g., respiratory suppression, less frequently seizures) were observed at 5.6 or 18 mg/kg, suggesting that at least in some strains, it is not possible to obtain stimulation of locomotor activity by increasing the dose. Taken together, those findings may suggest a shift in the balance between pre-and postsynaptic D2 receptors in mice relative to rats, such that stimulation of the former outweighs the latter.

The above hypothesis notwithstanding, the biological background for the species and strain differences in the effects of D2-like agonists is not known and could have many other explanations. Spontaneous activity levels did not predict the direction of quinelorane’s effects: quinelorane increased locomotor activity in a strain ranking high in spontaneous activity (CAST/EiJ), a strain with intermediate spontaneous activity (SPRET/EiJ) and some rodents with relatively low spontaneous activity levels (C3H/HeJ mice and Sprague Dawley rats). The fact that the strains that exhibited the highest levels of spontaneous activity showed the greatest decreases in activity measured as a difference from baseline may simply reflect the range of possible effect available (i.e., less active strains progressively neared a “floor” effect). Fischer 344 rats and B6C3F1 mice were found to metabolize quinelorane differently, but the metabolites recovered in the mice were largely comparable to those recovered from rhesus monkeys, indicating mice do not metabolize this drug in a “unique” way (Manzione, Bernstein & Franklin, 1991). Since various drugs of different chemical structures have produced comparable effects in mice, it also appears unlikely that all D2-like agonists would yield active metabolites differentially in rats and mice, with similar effects. Spontaneous activity levels did not predict whether a strain showed increased or decreased activity with quinelorane. Spontaneous activity did correlate positively with peak decreases in activity, and negatively with peak decreases as difference from baseline. Striatal dopamine content was found to vary between strains, with more to less dopamine: 129X1/SvJ > DBA/2J > C3H/HeJ > C57B/6J = A/J = BALB/cJ > BALBcByJ > SPRET/EiJ = CAST/EiJ (Mhyre et al., 2005; Skrinskaya, Nikulina & Popova, 1992). While there is also no apparent correlation between this ranking and whether quinelorane increased or decreased activity in the present investigation, the higher dopamine-content strains tended to show the smallest decreases in activity (as peak difference from vehicle). This may appear in contradiction to the positive correlation between magnitude of effect and spontaneous activity if high dopamine content is hypothesized to result in high spontaneous activity, but it should be noted that both studies reported total, not extracellular, dopamine, and that regions other than dorsal striatum may be more important in regulating activity levels in mice (Mhyre et al. 2005; Skrinskaya, Nikulina & Popova, 1992). Although differences in dopamine receptor densities have been reported, they do not offer any clear explanations for the results of the present investigation. For example, strains fell into two groups of “high” and “low” striatal D2 density, with higher D2-like binding (Bmax) in A/J, BALB/cJ, C3H/HeJ and CD-1 mice, and approximately 50% lower values in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice, in two independent studies (Boehme & Ciaranello, 1981; Helmeste & Seeman, 1982). It should also be kept in mind that we tested just one D1 agonist and one D2 agonist, and that other compounds could yield different patterns of strain sensitivities.

The lack of locomotor stimulant effect of D2-like agonists also appears to generalize to other behavioral endpoints. For example, PPI can be suppressed in humans and rats by D2-like agonists, and to a lesser extent by D1-like agonists, yet only D1-like agonists decreased PPI in several mouse strains, including 129S6/SvEvTac, 129X1/SvJ, C57BL/6J and Swiss-Webster (Chang, Geyer, Buell, Weber & Swerdlow, 2010; Geyer, Krebs-Thomson, Braff & Swerdlow, 2001 for review; Ralph & Caine, 2005; Ralph-Williams, Lehmann-Masten, & Geyer, 2003). Studies in knockout mice maintained on a C57BL/6 background also supported a role of D1 rather than D2 receptors in mediating PPI suppression by direct dopamine agonists, similar to locomotor stimulant effects (Ralph-Williams, Lehmann-Masten, Otero-Corchon, Low & Geyer, 2002). For the three mouse strains that showed locomotor stimulation by quinelorane in the present study, C3H/HeJ, CAST/EiJ and SPRET/EiJ, there was also agreement between locomotor and PPI data, as quinelorane also decreased PPI in all three strains (Ralph & Caine, 2007). For the DBA/2J strain, PPI and locomotor data show some discrepancy, in that only quinelorane decreased PPI in this strain, while only R-6-Br-APB increased locomotor activity in a previous study as well as the present findings (Ralph & Caine, 2005). It will be interesting to see if those findings with PPI in the DBA/2J strain are replicable, as this strain, although inbred, has shown considerable variability in other studies (see Thomsen & Caine, submitted, for discussion). Other behavioral endpoints may also show species differences. For instance both Swiss-Webster and C3H-HeJ mice, as well as D2, D3 or D4 knockout mice backcrossed to C57BL/6J, were reported to lack the yawning response which D2-like agonists elicit in rats and monkeys, an effect tentatively attributed to D3 stimulation (Bristow et al., 1996; Collins et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Martelle et al., 2007). While those findings show agreement across endpoints for the Swiss Webster mice, they suggest (if confirmed) that C3H/HeJ mice may not parallel rat findings in all behavioral endpoints. In contrast to locomotor activity or PPI, some effects of D1-like and D2-like agonists appear to be more consistent across species. We have shown that both D1-like and D2-like agonists (SKF 82958, quinelorane) can maintain self-administration in mice trained to self-administer cocaine, at least in C57BL/6J mice or mice of mixed 129×C57BL/6J background (Caine et al., 2002, 2007; Thomsen, Hall, Uhl & Caine, 2009). Similarly, D2-like and D1-like agonists have been reported to maintain self-administration in rats and monkeys (Caine & Koob, 1993; Caine et al., 1999; Grech et al., 1996; Nader & Mach, 1996; Self & Stein, 1992; Woolverton, Goldberg & Ginos, 1984; Weed & Woolverton, 1995).

Species and strain differences in effects of R-6-Br-APB

Increases in locomotor activity following administration of D1-like agonists have previously been reported in 129X1/SvJ, AKR/J, BALB/cCrSlc, C57BL/6J, DBA/2J, and Swiss Webster mice (Desai, Terry & Katz, 2005; Geter-Douglass, Katz, Alling, Acri & Witkin, 1997; Halberda, Middaugh, Gard & Jackson, 1997; Niimi, Takahashi & Itakura, 2009; Ralph & Caine, 2005, 2007; Tirelli & Terry, 1993). Thus, as opposed to the findings for D2 agonists, most mouse strains showed effects of D1 stimulation similar to those observed in rats in locomotor activity assays. The present data confirmed and extended those findings to further strains, and identified a minority of strain in which R-6-Br-ABP failed to increase locomotor activity. Two mouse strains showed no effect of R-6-Br-APB on total beam breaks: the A/J and CAST/EiJ. Three mouse strains showed only decreases in total beam breaks after R-6-Br-APB administration: the FVB/NJ and both substrains of BALB. It is noteworthy that those were the three strains exhibiting the higher baseline activity levels, although it is unlikely that a “ceiling effect” accounts for the lack of stimulation, as cocaine increased locomotor activity in both FVB/NJ and BALB/cByJ mice (Thomsen & Caine, submitted). It is intriguing that the strains which failed to respond to D1 stimulation with hyperactivity comprise the BALB substrains, which generally failed to self-administer cocaine in previous investigations (Deroche et al., 1997; see Thomsen & Caine, submitted, for cocaine self-administration data and detailed discussion). The BALB/cJ was the only strain in which cocaine failed to increase activity in our laboratory (Thomsen & Caine, submitted), and it is possible that the same “quirk” in this strain accounts for the lack of stimulation for both drugs in the present study. In addition, knockout mice lacking D1 receptors failed to self-administer cocaine, indicating a key role of D1 receptors in mediating cocaine’s reinforcing effects in mice (mixed 129X1/SvJ×C57BL.6J background; Caine et al., 2007). We are not aware of cocaine self-administration studies using the A/J, CAST/EiJ, or FVB/NJ strains, but it would be interesting to note whether D1-induced locomotor hyperactivity might be as good or better a predictor of cocaine’s reinforcing effects in mice, relative to cocaine-induced hyperactivity.

The biological basis for the strain differences in response to D1 stimulation is unknown. As mentioned above, striatal dopamine content has been found to vary between strains, with more to less dopamine: 129X1/SvJ > DBA/2J > C3H/HeJ > C57B/6J = A/J = BALB/cJ > BALBcByJ > SPRET/EiJ = CAST/EiJ (Mhyre et al., 2005; Skrinskaya, Nikulina, & Popova, 1992). This ranking appears to correlate inversely with the magnitude of stimulation by R-6-Br-APB observed in the present investigation (peak effect as difference from vehicle), with the exception of the A/J strain, in which R-6Br-APB did not affect activity levels. Experiments with recombinant inbred strains derived from A/J and C57BL/6J identified chromosome regions conferring differential locomotor response to cocaine. Candidate genes within those regions could also help explain the lack of locomotor response of the A/J mice to D1 receptor stimulation, specifically, the genes encoding the D1, (D2) and D5 receptors, as well as regions related to the regulation of striatal D1 (and D2) receptor densities (Gill & Boyle, 2003). The animals used in the present investigation had previously been exposed to cocaine in a similar study, and it cannot be excluded that this pre-exposure may have modulated the sensitivity to D1 (and D2) agonists differentially between strains. However, preliminary data in experimentally naïve Swiss Webster mice, as well as previously published data in rats, Swiss Webster, 129X1/SvJ, C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice, were comparable to those reported here (data not shown and Ralph & Caine, 2005).

As with quinelorane, there was generally good agreement between the effects reported in this investigation and previous data in the PPI assay: R-6-Br-APB decreased PPI in Sprague Dawley rats and Swiss Webster, 129S6/SvEvTac, 129X1/SvJ, C3H/HeJ, C57BL/6J, and SPRET/EiJ mice, but not DBA/2J or CAST/EiJ mice (Ralph & Caine, 2005, 2007; Ralph-Williams, Lehmann-Masten & Geyer, 2003). In other words, as for quinelorane, only the DBA/2J strain showed some discrepancy between the two behavioral endpoints. Further, cocaine and direct dopamine agonists reduced PPI in wild-type mice (C57BL/6J background) and knock-out mice lacking D2 receptors, but not in D1 receptor knockout mice (Doherty et al., 2008; Ralph-Williams, Lehmann-Masten, Otero-Corchon, Low & Geyer, 2002). As discussed above, we have also found that the D1-like agonist SKF 82958 can serve as a positive reinforcer in mice (Caine et al., 2002, 2007; Thomsen, Hall, Uhl & Caine, 2009). While self-administration behavior in monkeys and rats has often been less robust than for D2-like agonists, D1-like agonists also appear to maintain self-administration under some conditions in both rats and monkeys, further suggesting effects of D1-like agonists are generally consistent across species, relative to D2-like agonist effects (Caine, Negus, Mello & Bergman, 1999; Grech, Spealman & Bergman, 1996; Self & Stein, 1992; Weed & Woolverton, 1995).

Qualitative effects of quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB on locomotor behavior: distribution of beam breaks between consecutive, repeated, and elevated

For both quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB, changes in total activity were rather consistently paralleled by relative (percent) changes in consecutive beam breaks (consistent with ambulation), by repeated breaks of the same beam (consistent with fine movements) or by breaks of the elevated beams (consistent with rearing). The proportion of repeated beam breaks was correspondingly modulated in the opposite direction, while elevated beam breaks tended to be decreased or unchanged by quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB. Inspection of the dose-effect functions in each beam break type confirmed that consecutive beam breaks increased with dose in the strains that showed increases in total activity, and decreased in strains that showed decreases in total activity, for both drugs. Thus even for strains showing a high proportion of repeated beam breaks at baseline, consecutive beam breaks (likely reflecting ambulation), appeared to be the major contributor to the effects observed as total activity.

The occurrence of stereotyped behaviors was not evaluated in the present investigation, but quantitative observations in other studies using the same procedure suggested repeated beam breaks correlates roughly with stereotypy scores, in both rats and mice (129X1/SvJ and C3H/HeJ; manuscript in preparation). Thus, increases in repeated beam breaks in strains that showed decreased total activity might indicate the induction of stereotyped behaviors. However, closer inspection of the data revealed that relative increases in the percent repeated beam breaks did not reflect absolute increases, but rather reflected smaller decreases in repeated than consecutive beam breaks, or unchanged repeated beam breaks relative to decreased consecutive beam breaks. In addition, we observed dose-dependent stereotyped behaviors (e.g., nose twitch, head vibration/head bob) with 6-Br-APB in Sprague Dawley rats, 129X1/SvJ mice and C3H/HeJ mice, and with quinelorane only in the rats (manuscript in preparation). Similarly, a D1 agonist, but not a D2 agonist, induced stereotypic climbing in BALB/c, C3H/He, C57BL/6, and DBA/2 mice (note: not from Jackson laboratories, Skrinskaya, Nikulina & Popova, 1992). Both D1-like and D2-like agonists failed to induced gnawing in C57BL/6J mice in a previous study (Tirelli & Witkin, 1995). Overall, it is unlikely that decreases in consecutive beam breaks (ambulation) or total activity were attributable to the induction of stereotypies.

The only strain in which quinelorane failed to change total beam break counts significantly at any dose was the SJL/J, and this strain also was the only one in which quinelorane did not affect the distribution of beam breaks significantly. R-6-Br-APB failed to significantly alter total activity in A/J mice and CAST/EiJ mice. While R-6-Br-APB also failed to significantly affect the distribution of beam breaks by type in the A/J mice, there was a small but significant modulation in the CAST/EiJ mice. Indeed, R-6-Br-APB increased the percentage of repeated beam breaks in this strain, an effect which actually reflected net decreases in both consecutive and elevated beam breaks while repeated beam breaks remained fairly stable. Thus there was no consistent pattern relating lack of effects in total activity to lack of modulation of beam break type distribution. It is also worth noting that all strains showed some effect, whether increase or decrease in activity, with at least one of the drugs (i.e., no strain was “unaffected” by both drugs).

In summary, while hallmark effects of dopamine receptor stimulation such as locomotor hyperactivity, PPI suppression, or reinforcing effects, are obtained most robustly and consistently in rats with D2-like agonists, those effects appear to be obtained exclusively or most consistently in most mouse strains with D1-like agonists. Only two mouse strains (C3H/HeJ and SPRET) showed stimulant effects of quinelorane and R-6-Br-APB both, similar to rats. If such a profile is desirable for a given experiment, however, only the C3H/HeJ would seem a viable candidate for genetically engineered mice because of prohibitive price, delicate health and handling difficulties of the SPRET. Our data indicate that there are mouse strains available in which only D1-like agonists, both D1-like and D2-like agonists, or only D2-like agonists, or neither D1-like nor D2-like agonists, stimulate locomotor activity, thus offering a wide range of genetic tools for future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cynde Harmon, Jill Berkowitz, Gloria Yu, Justin Hamilton, and Jennifer Dohrmann for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA07252, DA12142) and the Zaffaroni Foundation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no financial relationship with the organization that sponsored the research. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review those data if requested.

REFERENCES

- Bergman J, Kamien JB, Spealman RD. Antagonism of cocaine self-administration by selective dopamine D(1) and D(2) antagonists. Behav Pharmacol. 1990;1(4):355–363. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199000140-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehme RE, Ciaranello RD. Dopamine receptor binding in inbred mice: strain differences in mesolimbic and nigrostriatal dopamine binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(5):3255–3259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38(9):1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Rostene W, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D3 receptor agonists produce similar decreases in body temperature and locomotor activity in D3 knock-out and wild-type mice. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38(4):555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow LJ, Cook GP, Gay JC, Kulagowski JJ, Landon L, Murray F, et al. The behavioural and neurochemical profile of the putative dopamine D3 receptor agonist, (+)-PD 128907, in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35(3):285–294. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Reid LR, Nichols CL, Kornfeld EC, Wong DT. Elevation of acetylcholine levels in striatum of rat brain by LY163502, trans-(−)-5,5a,6,7,8,9a,10-octahydro-6-propylpyrimido less than 4,5-g greater than quinolin-2-amine dihydrochloride, a potent and stereospecific dopamine (D2) agonist. Life Sci. 1986;38(4):317–322. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Koob GF. Modulation of cocaine self-administration in the rat through D-3 dopamine receptors. Science. 1993;260(5115):1814–1816. doi: 10.1126/science.8099761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Negus SS, Mello NK, Bergman J. Effects of dopamine D(1-like) and D(2-like) agonists in rats that self-administer cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291(1):353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]