Men who have sex with men (MSM) remain the largest population infected with HIV in the United States [1]. Although early (offline) prevention efforts were effective in reducing the spread of HIV [2], there has been a reversal in safer sex practices since the mid-1990s [3], leading researchers to conclude that HIV prevention efforts for MSM in the US have “faltered” [4]. Re-energizing HIV prevention for MSM remains an urgent priority in the fight against HIV/AIDS [5].

Increased sexual risk taking and rising HIV rates among MSM have coincided with the broad adoption of the Internet as a way for MSM to meet sexual partners [6]. The Internet is now the largest venue where MSM meet sexual partners [7]. A meta-analysis of 14 studies from 1999 to 2005 reported a weighted mean estimate of 40% of MSM meeting their sex partners online [8]. However, the analysis is now dated, the range of estimates was large (23% to 99%) and highly dependent upon the recruitment methods used [8].

Clinic studies have identified Men who use the Internet to seek sex with men (MISM) as at higher risk for HIV/STIs than other MSM [9]. Internet sex-seeking appears to increase risk through an increased number of partners [10] and therefore increased probability of sexual risk behavior [6, 11]. Tracing STI outbreaks [12] and HIV transmission [13] through Internet-mediated liaisons is well-documented.

Given the global reach of the World Wide Web, its accessibility, affordability, anonymity, and popularity for sex-seeking among MSM [14], Internet-based interventions hold exceptional promise to address the global pandemic of HIV among MSM if they can be shown to reduce unsafe sexual behavior. The long-term objective of this research is to develop Internet-based interventions strong enough to lower sexual risk behavior among MISM.

To date, three online interventions for adult MISM have been rigorously evaluated. These programs used tailored messaging to MISM entering relationships [15], visual stories to promote HIV testing and to reduce unsafe sex [16], and “gay” avatars on a virtual cruise [17]. However, two of the trials [15, 17] experienced attrition rates of 70–80%, preventing meaningful interpretation of results, while the third [16] did not attempt to measure behavior change. Thus, attrition in online interventions appears a major challenge.

Study Description

The Men’s INTernet Study-II (MINTS-II) is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test whether an Internet-based sexual health promotion intervention (Sexpulse) for MISM can reduce their unprotected anal intercourse. Participants completed the study during a 3-week period from December 2007 to January 2008 with 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up surveys being sent in April, July, October and January 2009, respectively.

Development of the Intervention

Sexpulse was designed by a multidisciplinary team of health professionals, computer scientists, and e-learning specialists and developed by a leading e-learning development company. Extensive formative research was undertaken with 2,716 MISM recruited online [11, 18]. Key findings were that to be acceptable to the target population, online HIV prevention must be comprehensive, highly visual, and more sexually explicit than conventional prevention programs [18].

Our theoretical approach was grounded in the Sexual Health Model approach to HIV prevention [19] and principles from e-learning [20]. The Sexual Health Model posits that sexually healthy persons are more likely to make sexually healthy decisions, while e-learning stresses that to be effective, online interventions should be user-oriented, engaging, informative, and fun. For our starting point, we adapted a seminar-based sexual health curriculum for MSM into an online intervention [21].

From the perspective of persuasive computing [22], we consider the role of computers as tools (persuasion through customization and tunneling), media (simulation and experience), and social actors (roles). We paid specific attention to human-computer interaction [23] and user experience, using testing to remove distractions that would lessen participant engagement with the intervention. The intervention was modular with extensive user flexibility to maintain the feeling of control typical in both graphical user interfaces and Web interaction. The modules borrowed most directly from computer games, which have a long history of presenting persuasion opportunities [24], but also incorporated video segments, interactive text and animations.

Module prototypes were developed using a multi-iteration design and development process. Prototypes were reviewed both internally by experts, tested with MISM in a usability laboratory, and refined as needed.

Intervention Description

In translating the curriculum into an online experience, the didactic approach was dropped in favor of active learning. From the participant’s perspective, the overall goal of the intervention was presented as building a personal “portrait of sexual health,” with each module yielding a portrait piece. Module examples include a “hot sex” calculator, which calculates the odds of great sex while demonstrating decision making in dating; a virtual gym where men can explore body image concerns common in this population; an online chat simulation where users can explore ambiguity and evasion; and a reflective journey where participants can identify and graph the effects of past successes and disappointments, identify long-term goals, shed secrets and deepen spirituality. These modules were supplemented by virtual peers who contributed their experiences from diverse perspectives, reinforcements in the form of 15-second cartoons, polls where participants could compare their answers with those of other participants, and FAQs where learners could seek specific information. Two modules employed personal video vignettes of three MSM living with HIV and three HIV-negative MSM discussing ways they avoid transmitting/acquiring HIV. Other modules covered mental and emotional health, physical health, intimacy, relationships, sexuality, and spirituality aspects of the Sexual Health Model, with each module addressing implications for safer sex, commitment to reducing risk, and long-term sexual health.

Methods

Participant Recruitment Procedures

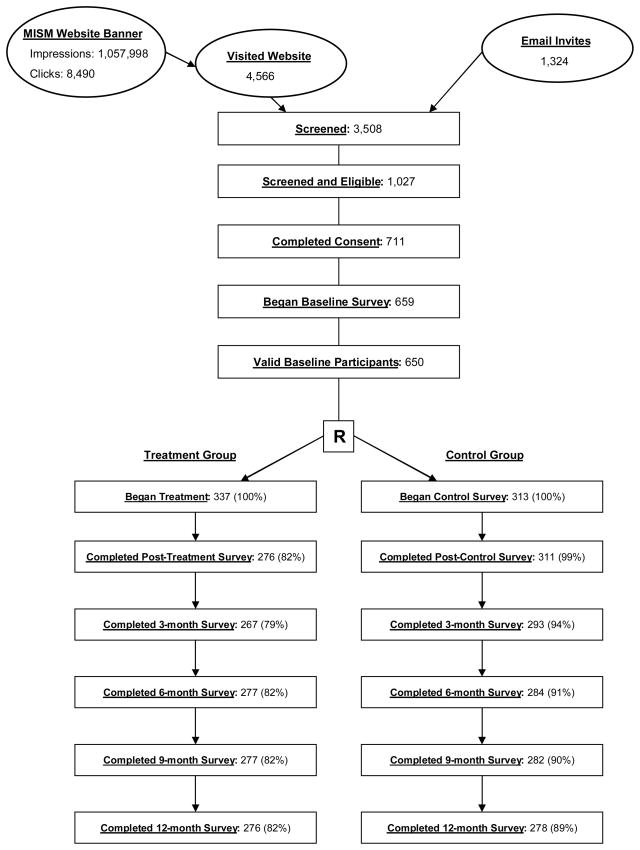

Banner advertisements placed on two of the nation’s largest gay websites and emails to participants from previous research connected MISM to the study webpage [see Figure 1]. Eligibility criteria included being male, 18 years or older and a US resident, with a recent history of engaging in unprotected anal intercourse with at least one other man. In addition, potential participants were informed they would need to be comfortable viewing sexually explicit materials online, be prepared to complete all online activities within seven days, and be willing to provide an email address and phone number to maintain contact. All study protocols were approved by our institution’s IRB.

Figure 1.

MINTS-II RCT Data Collection

Strategies to Improve Retention

High attrition in prior Internet-based HIV prevention trials was a concern [15–17]; hence, we focused on strategies to improve participant retention. Prior research identified time constraints and inadequate compensation as reasons MISM drop out of online studies. Therefore, compensation was set at $80 for completing the pretest, intervention and post-test, with an additional $20–25 for completing each follow-up survey. This amount was deemed sufficient, but not coercive, for retention. Second, we employed a quarterly e-raffle with a monetary first prize of $150 to maintain study contact. Third, we developed a retention protocol where failure to return a survey triggered automated reminders, followed by personalized human contact by email and then telephone.

Experimental Conditions

All participants were invited to complete baseline, immediate post-intervention, and 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-up surveys. A computer algorithm was used to randomly assign participants to one of two experimental conditions. Participants assigned to the null control condition completed an additional sexual health survey between baseline and post-intervention assessments. Participants assigned to the intervention arm completed Sexpulse. Seven days after enrollment, participants who had not completed the null control survey or Sexpulse were sent two automated email reminders (one week apart), and were then contacted by telephone. At each follow-up, reminder e-mails were sent asking participants to return to the website to complete follow-up surveys.

Measures

The primary end point for the trial was the self-reported number of male partners with whom a participant engaged in unprotected anal sex (UAIMP) during the prior 90 days. In addition, the pretest survey assessed other dimensions of sexual health and collected demographic and Internet-use information. Immediate post-intervention surveys assessed participants’ ratings of the intervention and qualitative comments on strengths and weaknesses of the intervention.

Results

Figure 1 presents the enrollment, allocation and retention results. A total of 650 MISM completed the baseline survey and were randomized to one of the experimental conditions. Retention over the 12-month study ranged between 76% and 99%.

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics and displays the covariate balance achieved through randomization. Except for a 6.3% larger proportion of white men and modest differences in the distributions of age and educational attainment, randomization procedures appear to have balanced background characteristics across treatment conditions.

Table 1.

Demographic and Health Characteristics of Participants at Baseline (n=650)

| Total, n (%) | Treatment Arm, column % | Control Arm, column % | % Difference between arms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (in years)

| ||||

| 18–25 | 153 (23.5) | 24.0 | 23.0 | 1.0 |

| 26–35 | 224 (34.5) | 33.5 | 35.5 | 2.0 |

| 36–45 | 180 (27.7) | 27.3 | 28.1 | 0.8 |

| Older than 45 | 93 (14.3) | 15.1 | 13.4 | 1.7 |

|

| ||||

|

Race/Ethnicity

| ||||

| Caucasian/White | 443 (68.2) | 71.2 | 64.9 | 6.3 |

| Black or African American | 41 (6.3) | 5.3 | 7.4 | 2.1 |

| Latino/Spanish/Other | 98 (15.1) | 13.1 | 17.3 | 4.2 |

| Asian | 23 (3.5) | 2.7 | 4.5 | 1.8 |

| Other | 45 (6.9) | 7.7 | 6.1 | 1.6 |

|

| ||||

|

Educational Attainment

| ||||

| Less than high school or high school graduate | 51 (7.9) | 8.6 | 7.0 | 1.6 |

| Some college education | 223 (34.3) | 34.7 | 33.9 | 0.8 |

| College degree | 147 (22.6) | 22.0 | 23.3 | 1.3 |

| Graduate/Professional School | 229 (35.2) | 34.7 | 35.8 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||

|

Annual Income

| ||||

| Less than $20,000 | 121 (18.6) | 19.3 | 17.9 | 1.4 |

| $20,000–$31,999 | 127 (19.5) | 18.1 | 21.1 | 3.0 |

| $32,000–$44,999 | 117 (18.0) | 17.8 | 18.2 | 0.4 |

| $45,000–$64,999 | 124 (19.1) | 20.2 | 17.9 | 2.3 |

| Greater than $65,000 | 133 (20.5) | 20.5 | 20.5 | 0.0 |

| Refuse to answer | 28 (4.3) | 4.2 | 4.5 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||

|

Employment Status

| ||||

| Technical profession | 76 (11.7) | 8.9 | 14.7 | 5.8 |

| Business profession | 188 (29.0) | 28.9 | 29.2 | 0.3 |

| Human services profession | 117 (18.1) | 18.8 | 17.3 | 1.5 |

| Sales/Clerical | 59 (9.1) | 9.8 | 8.3 | 1.5 |

| Student | 115 (17.8) | 17.6 | 18.0 | 0.4 |

| Skilled worker | 43 (6.6) | 8.6 | 4.5 | 4.1 |

| Unskilled worker | 6 (0.9) | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| Unemployed | 27 (4.2) | 3.9 | 4.5 | 0.6 |

| Retired | 17 (2.6) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||

|

Residence

| ||||

| Rural or small town | 104 (16.1) | 17.1 | 15.1 | 2.0 |

| Medium sized city | 106 (16.4) | 18.0 | 14.7 | 3.3 |

| Suburb of a large sized city | 155 (24.0) | 24.0 | 24.0 | 0.0 |

| Downtown or central district of a large sized city | 281 (43.5) | 41.0 | 46.2 | 5.2 |

|

| ||||

|

Number of Children

| ||||

| 0 | 600 (92.6) | 92.9 | 92.3 | 0.6 |

| 1–2 | 38 (5.9) | 5.4 | 6.4 | 1.0 |

| 3 or more | 10 (1.5) | 1.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

|

| ||||

|

Sexual Orientation

| ||||

| Homosexual/Gay/Same Gender Loving | 594 (91.4) | 90.8 | 92.0 | 1.2 |

| Bisexual/Straight/Other | 56 (8.6) | 9.2 | 8.0 | 1.2 |

|

| ||||

|

HIV Status

| ||||

| HIV-positive | 140 (21.6) | 20.8 | 22.4 | 1.6 |

| HIV-negative | 508 (78.4) | 79.2 | 77.6 | 1.6 |

|

| ||||

|

Long Term Partner

| ||||

| Yes | 159 (24.5) | 24.0 | 24.9 | 0.9 |

| No | 491 (75.5) | 76.0 | 75.1 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||

|

Current/Ever Member of Gay Organization

| ||||

| Yes | 340 (52.4) | 53.7 | 51.0 | 2.7 |

| No | 309 (47.6) | 46.3 | 49.0 | 2.7 |

Table 2 presents the 3-month and 12-month change in HIV risk (UAIMP) in the past 3 months. We note the observed distribution of UAIMP was highly skewed—most men reported UAI with a few male partners, and a small number of men reported many such partners. Accordingly, it can be seen that that 20% of participants in both experimental conditions did not report any risk change at the 3-month follow-up. Unfortunately, 12% of the control arm, compared to 10% in the treatment arm, reported more than one additional UAIMP at follow-up.

Table 2.

3-Month and 12-Month Change in Incident UAIMP, by Treatment Arm

| Difference in Partners between Baseline and 3-months

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Arm, % (n=267) | Control Arm, % (n=292) | Difference | Ratio* | |

| More than 1 fewer partners | 40.8 | 38.4 | 2.5 | 1.064 |

| One fewer partner | 21.0 | 20.9 | 0.1 | 1.004 |

| No change in partners | 20.2 | 20.2 | 0.0 | 1.000 |

| One more partner | 8.2 | 8.2 | 0.0 | 1.002 |

| More than 1 additional partner | 9.7 | 12.3 | −2.6 | 0.790 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | - |

| Difference in Partners between Baseline and 12-months

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Arm, % (n=273) | Control Arm, % (n=277) | Difference | Ratio* | |

| More than 1 fewer partners | 39.2 | 50.5 | −11.3 | 0.775 |

| One fewer partner | 24.2 | 21.7 | 2.5 | 1.116 |

| No change in partners | 17.2 | 13.0 | 4.2 | 1.325 |

| One more partner | 7.3 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 1.268 |

| More than 1 additional partner | 12.1 | 9.0 | 3.1 | 1.339 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | - |

Ratio = Treatment Value/Control Value

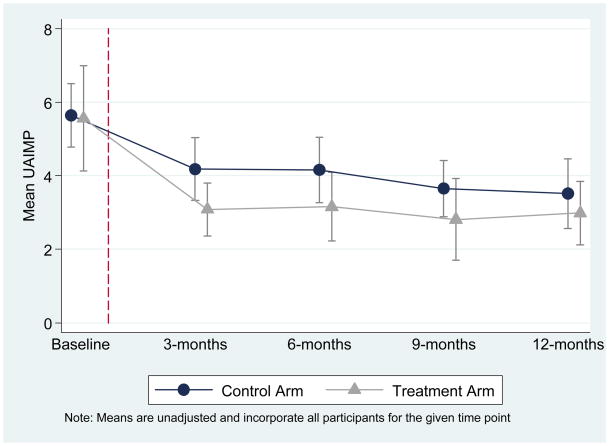

Another way to examine change is displayed in Figure 2, which presents the adjusted mean UAIMP (and 95% confidence bands) by measurement period and experimental condition. Clearly, the point estimates within condition diverge after treatment, although confidence bands overlap. It is also important to note that self-reported risk declined in both the treatment and control conditions.

Figure 2.

Mean Number of Male UAI Partners (UAIMP) by Time Point and Treatment Group, (N=650 MISM at Baseline)

Table 3 presents results from negative binomial regression models, which estimate the treatment effect as a rate ratio. The upper panel presents treatment effects at 3 months, and the lower panel presents results at 12-month follow-up. Table 3 also presents results for all participants (i.e., full sample) and only those with some risk at baseline (i.e., non-zero risk), which could have been reduced by the intervention. Finally, both crude (i.e., unadjusted) and adjusted estimates are presented. The modeled results suggest that the Sexpulse program reduced short-term risk by an estimated 16.8% (95% CI: 0.69, 1.00; p=0.05) in the unadjusted and by 15.6% (95% CI: 0.704, 1.013; p=0.068) in the adjusted full sample models. Similar effects are observed in those who reported some baseline risk. By 12-month follow-up, no meaningful differences between treatment and control conditions are observed.

Table 3.

Treatment Effect Estimates from Random Effects Negative Binomial Regression Models of UAIMP at both 3-months and 12-months on Treatment Indicator among Full Sample and among Users who Reported Risk at Baseline

| N | Incident Rate Ratio (IRR) | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 month outcome

| |||||

| Full Sample | |||||

| Unadjusted | 650 | 0.832 | 0.691 | 1.000 | 0.050 |

| Adjusted* | 650 | 0.844 | 0.704 | 1.013 | 0.068 |

|

| |||||

| Non-zero Risk at Baseline** | |||||

| Unadjusted | 584 | 0.825 | 0.684 | 0.995 | 0.044 |

| Adjusted* | 584 | 0.843 | 0.701 | 1.014 | 0.069 |

|

| |||||

|

12 month outcome

| |||||

| Full Sample | |||||

| Unadjusted | 650 | 0.998 | 0.952 | 1.046 | 0.921 |

| Adjusted* | 650 | 0.998 | 0.952 | 1.046 | 0.937 |

|

| |||||

| Non-zero Risk at Baseline** | |||||

| Unadjusted | 584 | 0.991 | 0.945 | 1.040 | 0.728 |

| Adjusted* | 584 | 0.993 | 0.947 | 1.042 | 0.786 |

Analyses not presented show no evident impacts of “dose,” operationalized as time spent completing Sexpulse. Further, the modeled estimates of Table 3 are robust to specification, such that adding or subtracting other potential confounders (e.g., HIV status) has no meaningful impact.

Discussion

There were three major findings in this study. First, it is possible to develop a highly interactive Internet-based intervention program that MISM can use. Second, it is possible to conduct an Internet-based RCT and retain MISM over long periods of time (76–99% over 12 months). Third, among our participants who reported UAIMP at baseline, at 3 months those randomized to the intervention group reported a marginally significant decrease in the number of men with whom they engaged in risk behavior compared to the control group. That longer-term follow-up showed no meaningful differences does not negate this promising fact. Taken together, the results suggest that the highly interactive online intervention can have at least short-term effects on reducing sexual risk behavior among MISM. Because reduction in UAIMP predicts lower HIV/STI incidence, the effects of the intervention carry considerable public health importance.

At least four directions for future research are implied by these results. First, our next steps include developing and testing methods to strengthen the long-term effects of the intervention. Second, we highlight the reduction in risk reported by participants in the control condition as a challenge (see Figure 2). While similar effects can be seen in offline randomized controlled trials (see, for example, Morin et al. [25]), research into panel conditioning and context effects is needed to better understand these results. Third, reach (getting people to the site) and retention (keeping people on site) have been identified as the two major challenges for internet-delivered interventions for adolescents [26–28]. We hypothesize these are also the major challenges for successful online interventions for MISM, and recommend researchers measure and report these in their evaluations. Finally, because online interventions can be accessed globally, next steps in this line of research include testing replicability, language equivalency, cultural appropriateness, and differences in effectiveness internationally.

Given the study design and the complexity of the intervention, it is not possible to identify the specific program components that led to behavior change in this study; a large and complicated factorial experiment is needed to definitively answer such questions. However, we speculate that the following factors contributed to the short-term effectiveness of our program: a Web site that was engaging, highly interactive, and fun, with a complexity of cognitive intervention tasks, based on the Sexual Health Model, informed by credible data, addressing topics identified by the target population as highly relevant, supported by personal testimonies, dominance of visual over verbal information including sexually explicit and realistic images, written in a real-world direct peer-to-peer style, and allowing participants to compare their responses to other peers. For enhancing retention, key features included a strong retention protocol, interactive engaging activities, appropriate visual learning elements, and, for this population and content, frequent use of realistic sexually explicit images.

There were four principal limitations to the study. First, Internet-based studies cannot guarantee that participants are actually members of the target population. Strategies employed in this trial to reduce the likelihood of false respondents included recruitment from sites exclusively targeting the intended population, eligibility screening prior to explanation of the study, an extensive consent process, and a strong de-duplication and cross-validation protocol to ensure internal consistency and reliability of responses. Second, the choice of a null control means that change may have been due to access to content, time and attention. The primary weakness of a null control is the potential for participant awareness that they did not receive the intervention. We considered a treatment-as-usual or a time-and-attention control option, but rejected the former as non-existent and the latter as not easy to identify. Third, participants completed the study under highly controlled conditions – including being required to complete all modules and being compensated. We cannot generalize from this trial how MISM may use it in the real world. Fourth, HIV risk assessments use self-reports of sexual behavior, which may be prone to recall and/or social desirability biases [29]. Although computer-based methods, such as those used in this study, appear to lessen such biases [30], accurate recall requires correct reconstruction of details and sequence of events [31, 32], with errors increasing for distantly occurring or high-frequency behaviors[33, 34]. While improbable, given the impossibility of blinding participants to treatment conditions, differential response-bias and related effects of attrition could explain results.

Our results have important implications for research and practice of HIV prevention, specifically, and more broadly for e-Public Health. This study demonstrates that challenges encountered by other e-Public Health research teams, including high attrition, can be overcome. Further, using a RCT design, Internet-based interventions appear potentially useful for reducing risk behavior. Future research should focus on establishing the effectiveness of online interventions and then comparing the effectiveness of new approaches to existing methods.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health (grant # 5R01-MH063688-05) and conducted under the oversight of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (#0405S59661). The team thanks Dr. Willo Pequegnat, at the National Institute of Mental Health, Office on AIDS Research, for her leadership in promoting Internet-based approaches to HIV prevention. We acknowledge with deep gratitude our co-investigators and consultants, Drs. Michael Allen, Walter Bockting, Eli Coleman, Gary Remafedi, Michael W. Ross and Brian Zamboni who provided invaluable contributions during the formative phases of this research; our research staff, Masaki Utsumiya, Curt Naumann and Kyle Feiner who implemented the study; and our Community Advisory Board. Allen Interactions, Inc. programmed the intervention, with Mr. Edmond Manning the lead instructional designer.

Footnotes

About the authors:

B. R. Simon Rosser, PhD, MPH is principal investigator of the MINTS-II study and also wrote the first draft of the introduction, methods and discussion.

J. Michael Oakes, PhD is lead methodologist and statistician for the study who designed the analysis and wrote the results section.

Joseph Konstan, PhD is the lead computer scientist for the study who oversaw the design and development of the intervention, it’s testing and the testing and implementation of the online survey and methods. On this paper he wrote the sections specific to computer science.

Simon Hooper, PhD is the e-learning educational theorist who oversaw the software development process, and led the formative research process which informed the intervention.

Keith J. Horvath, PhD is the co-investigator who focused on the intervention’s effectiveness particularly on young MSM and on HIV+ populations. He attended weekly meetings, advised substantially on what the intervention and survey should look like, and co-wrote the introduction and discussion sections.

Gene P. Danilenko, PhD (cand.) is the project coordinator for the study. In addition to implementing all aspects of the study and overseeing their day-to-day operation, he contributed substantially to the science of this study by proposing study of e-learning constructs. His doctoral dissertation, based on this trial, examines the effectiveness of different instructional scaffolding on the effectiveness of the intervention. On this paper he wrote the section detailing e-learning practices.

Katherine E. Nygaard, MPH conducted all the analyses for this study under the supervision of Dr. Oakes. In this role she wrote the analysis section, conducted all analyses, and proposed some additional analyses (reported in this paper) that helped contextualize these results.

Derek Smolenski, PhD is a postdoctoral fellow who has worked on the MINTS-II study for the last year, and in addition, took the lead in conducting analyses about order effects (as requested by Reviewer 1).

We confirm that all authors participated in regular meetings overseeing the implementation of the study at a level appropriate for co-authorship and further contributed specifically to this paper either by writing sections and/or by providing substantial comments to improve the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2006. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stryker J, Coates TJ, De Carlo P, Haynes-Sanstad K, Shriver M, Makadon HJ. Prevention of HIV infection: Looking back, looking ahead. JAMA. 1995;273:1134–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaffe HW, Valdiserri RO, De Cock KM. The re-emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic in Men who have Sex with Men. JAMA. 2007;298:2412–2414. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piot P. “2031 initiative.” Looking to the year 2031 and anticipating where we are likely to be in terms of the epidemic and the response. XVII International AIDS Conference; 2008 3–8 August; Mexico City, Mexico. 2008. p. WESS0201. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosser BRS, Miner MH, Bockting WO, Ross MW, Konstan J, Gurak L, et al. HIV risk and the Internet: Results of the Men’s INTernet Study (MINTS) AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):746–756. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9399-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosser BRS, West W, Weinmeyer R. Are gay communities dying or just in transition? An International consultation from the Eighth AIDS Impact Conference examining structural change in gay communities. AIDS Care. 2008;20(5):588–595. doi: 10.1080/09540120701867156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:576–584. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204710.35332.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284:443–446. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elford J, Bolding G, Sherr L. Seeking sex on the Internet and sexual risk behaviour among gay men using London gyms. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;15(11):1409–1415. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107270-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosser BRS, Oakes JM, Horvath KJ, Konstan JA, Danilenko GP, Peterson JL. HIV Sexual Risk Behavior by Men who use the Internet to seek Sex with Men: Results of the Men’s INTernet Sex Study-II (MINTS-II) AIDS Behav. 2009;13(3):488–498. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9524-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klausner JD, Wolf W, Fischer, Ponce L, Zolt I, Katz MH. Tracing a syphilis outbreak through Cyberspace. JAMA. 2000;284:447–449. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashima K, Alt EN, Harwell JI, Fiebich-Perez DK, Flanigan TP. Internet sex-seeking leads to acute HIV infection: A report of two cases. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:285–286. doi: 10.1258/095646203321264926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiasson MA, Parsons JT, Tesoriero JM, Carr P, Hirshfield S, Remein RH. HIV behavioral research online. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):73–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidovich U, de Wit JB, Stroebe W. The effect of an Internet intervention for promoting safe sex between steady male partners - results and methodological implications of a longitudinal randomized controlled trial online. International AIDS Conference; 2004 July 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. 2004. p. WePeC6115. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowen AM, Horvath KJ, Williams ML. A randomized control trial of Internet-delivered HIV prevention targeting rural MSM. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:120–127. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kok G, Harterink P, Vriens P, De Zwart O, Hospers HJ. The Gay Cruise: Developing a theory- and evidence-based Internet HIV-prevention intervention. Sex Res Social Policy. 2006;3:52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooper S, Rosser BRS, Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Danilenko G. Men’s INTernet Sex II (MINTS-II) Team. An online needs assessment of a virtual community: What men who use the Internet to seek sex with men want in Internet-based HIV prevention. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:867–875. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9373-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson BE, Bockting WO, Rosser BRS, Rugg DL, Miner M, Coleman E. A sexological approach to HIV prevention: The sexual health model. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:43–57. doi: 10.1093/her/17.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen M. Michael Allen’s guide to e-learning: Building interactive, fun and effective learning programs for any company. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosser BRS, Bockting WO, Rugg DL, Robinson BE, Ross MW, Bauer GL, et al. A randomized controlled intervention trial of a sexual health approach to long-term HIV risk reduction for men who have sex with men: Effects of the intervention on unsafe sexual behavior. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(Supplement A):59–61. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.4.59.23885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fogg BJ. Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Preece J, Rogers Y, Sharp H, Benyon D, Holland S, Carey T. Human-computer interaction. Wokingham, England: Addison Wesley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogg BJ. Persuasive technology: Using computers to change what we think and do. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morin S, Shade SB, Steward WT, Carrico AW, Remein RH, Rothsetin C, et al. A behavioral intervention reduces HIV transmission risk by promoting sustained serosorting practices among HIV-infected Men who have Sex with Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(5):544–551. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818d5def. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brouwer W, Oenema A, Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, De Vries NK, Brug J. An exploration of factors related to dissemination of and exposure to Internet-based behavior change interventions aimed at adults: A Delphi study approach. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(2):e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crutzen R, de Nooijer J, Brouwer W, Oenema A, Brug J, de Vries NK. Internet-delivered interventions aimed at adolescents: A Delphi study on dissemination and exposure. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(3):427–439. doi: 10.1093/her/cym094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroder KEE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behaivor: III. Response to commentary. Ann Behav Med. 2003;29(2):96–99. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroder KEE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:104–123. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2602_03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson CP, Skowronski JJ, Larsen SF, Betz A. Autobiographical memory: Remembering what and remembering when. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feldman-Barrett L, Barret DJ. An introduction to computerized experience sampling in psychology. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2001;19(2):175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Croyle R, Loftus EF. Concordance between self-report questionnaires and coital diaries for women with sexually transmitted infections. In: Bancroft J, editor. Researching sexual behavior. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1997. pp. 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Downey L, Ryan R, Roffman R, Kulich M. How could I forget? Inaccurate memories of sexually intimate moments. J Sex Res. 1995;32:177–191. [Google Scholar]